Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

2.2 Hybrid Orbitals: Making a Model for Methane 59

PROBLEM 2.8 Why not allow a 2p orbital to overlap sideways with an s orbital?

Why would this not solve the problem of waste of the rear lobe (see below and

Fig. 2.10)?

Summary

There are two severe problems with the too-simple model for methane shown in

Figure 2.9. The hybridization model solves them both!

1. The electrons in the bonds are far from being as remote from each other as pos-

sible. The hybridization model yields four hybrid orbitals directed toward the

corners of a tetrahedron, the best possible arrangement.

2. Bonds are formed through overlap between the carbon 2p atomic orbitals and

hydrogen 1s orbitals, thus wasting the back lobes of the 2p orbitals. In the

hybridization model, overlap is much improved in the bonds formed using the

fat lobes of sp

3

orbitals and hydrogen 1s orbitals.Table 2.1 reviews the properties

of sp, sp

2

, and sp

3

hybrid orbitals.

So why didn’t we just tell you that methane is tetrahedral and be done with it

rather than taking several pages to explore that experimental observation? First of all,

learning science is not about gathering a collection of facts. Rather it is learning a

way of thinking—a way of solving problems—of reaching an approximate idea of how

Nature works. In science, we look at experimental data (methane has the formula

CH

4

, for example) and then postulate a model to explain our observations. In the

beginning,that model is almost certain to be either flawed or at the very least severe-

ly incomplete. So we test it against new data—against what can be learned from new

experiments, and modify our hypothesis. In this case, that process looks like this: We

find out that methane has no 90° angles—how can we change our model to get rid

of those errors and come to a better model of Nature? Ultimately, we come to the

tetrahedral structure. We have learned much from looking at why our early, too-

simple models were inadequate and from our process of investigation. You will forget

most of the facts in this book,eventually.No matter, you can always look them up here

or elsewhere. What we hope you will not forget is the investigative method used in

organic chemistry and all other sciences—and many, many other disciplines as well.

But it is a utilitarian world these days,and we can hear cries of,“just gimme the facts,

buster; I’m not in this course to learn about science,I just want to get on with my career

goals.”No! No! No! We would argue with you forever that if you feel this way, you are

making a profound, lifetime error, but even if such a goal is granted, there is a fatal

flaw in just giving the facts. Put simply, there is too much material to be learned this

year to memorize your way through it. You can survive at first, but somewhere about

+

–

TABLE 2.1 Properties of Hybrid Orbitals

Hybridization Constructed from Angle between Bonds (°) Examples

sp 50% s, 50% p 180 BeH

2

, linear HCH

sp

2

33.3% s, 66.7% p 120 BH

3

,BF

3

sp

3

25% s, 75% p 109.5 CH

4

,

NH

4

60 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

the middle of the first semester you will run out of memory, and there is no way (yet)

to install any more. If you try to get through this course by memorizing a set of facts,

you will almost certainly not succeed. Success in this course—and in much of life—

depends on learning how to think, how to reason sensibly from new data. So that’s

what we will try to do throughout this book, and we have begun right here.

METHANE

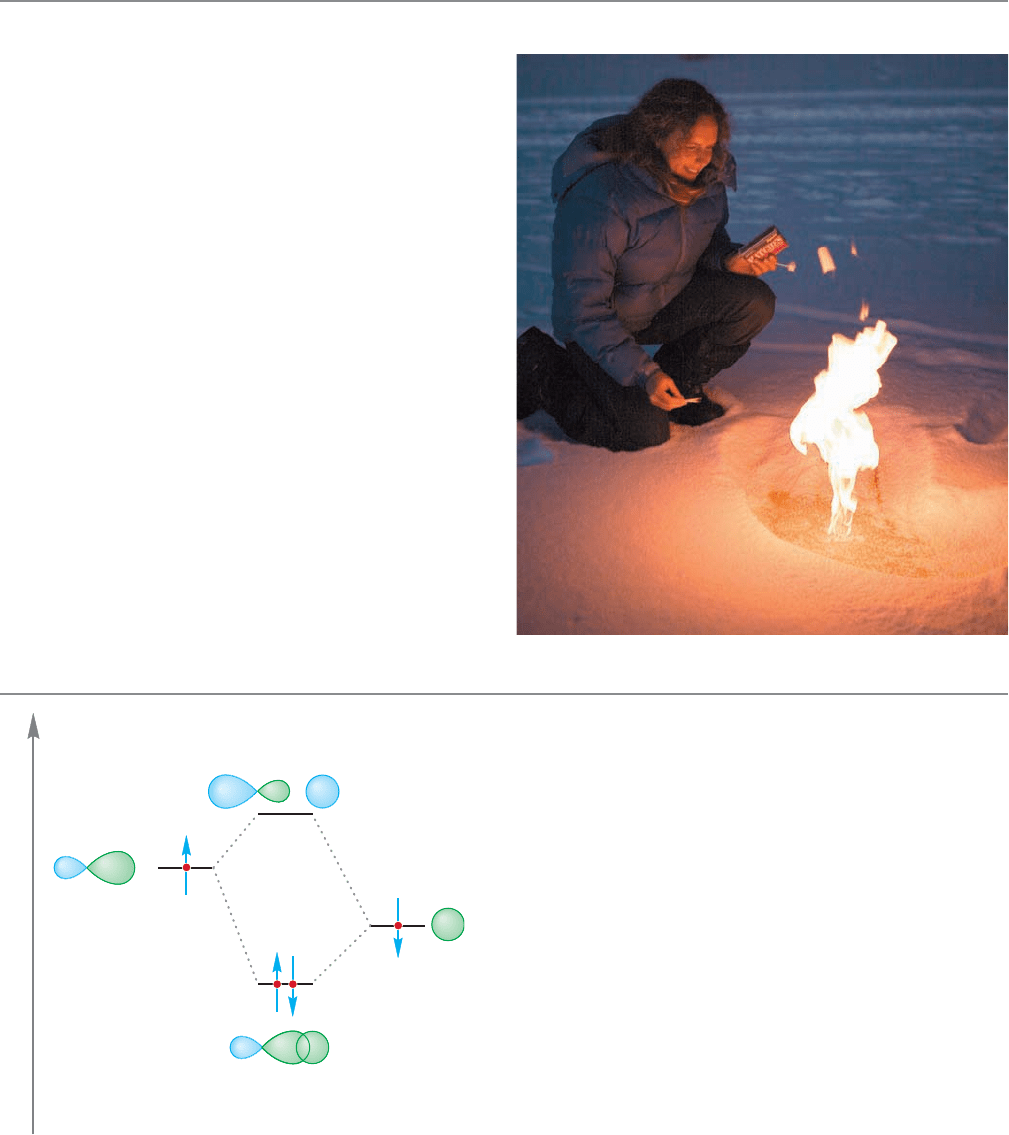

There is a lot of methane in very surprising places. Some

anaerobic bacteria degrade organic matter to produce methane.

When that process occurs deep in the ocean, water can crys-

tallize in a cubic arrangement, encapsulating methane mol-

ecules to form hydrates called clathrates. And those clathrates

can hold a lot of methane. One cubic meter of this hydrate

could contain as much as 170 m

3

of methane! Nor are those

clathrates merely rare curiosities. Estimates vary, but the

Arctic might hold as much as 400 gigatons, and worldwide

estimates (guesses, really) run to as much as 10,000 gigatons.

That’s a good news–bad news story. If we ever solve the

daunting economic problems involved in finding these

clathrates and getting the methane out, our hydrocarbon

scarcity problems vanish for a long time. On the other hand, if

that methane is ever released in an uncontrolled fashion (as it

regularly is in science fiction disaster stories), watch out!

Lest you think that last scenario fanciful, as you read

this, there are Siberian and Alaskan lakes formed from melt-

ing permafrost that bubble with escaping methane. The

University of Alaska’s Katey Walter, shown here setting one

of those lakes afire, is investigating those burbling lakes. She

and her associates suggest that earlier atmospheric methane

spikes were at least partially the result of the escape of large

amounts of this greenhouse gas.

2.3 The Methyl Group (CH

3

) and

Methyl Compounds (CH

3

X)

As soon as one of the four hydrogens surrounding the cen-

tral carbon in methane is replaced with another atom, pure

tetrahedral symmetry is lost. We might well anticipate that

one of the four sp

3

hybrid orbitals of carbon could overlap

in a stabilizing way with any atom X offering an electron

in any atomic orbital (Fig. 2.11). For maximum stabiliza-

tion,we want to fill the new, bonding molecular orbital cre-

ated from this overlap, which requires two, and only two,

electrons.

All manner of derivatives of methane, called methyl

compounds ( ), are possible. The atom or group

replacing H is called a substituent,and one option for nam-

ing these substituted compounds is to drop the “ane” from

the name of the parent molecule,methane,and append “yl.”

CH

3

O

X

Energy

sp

3

* = sp

3

– X

= sp

3

+ X

X

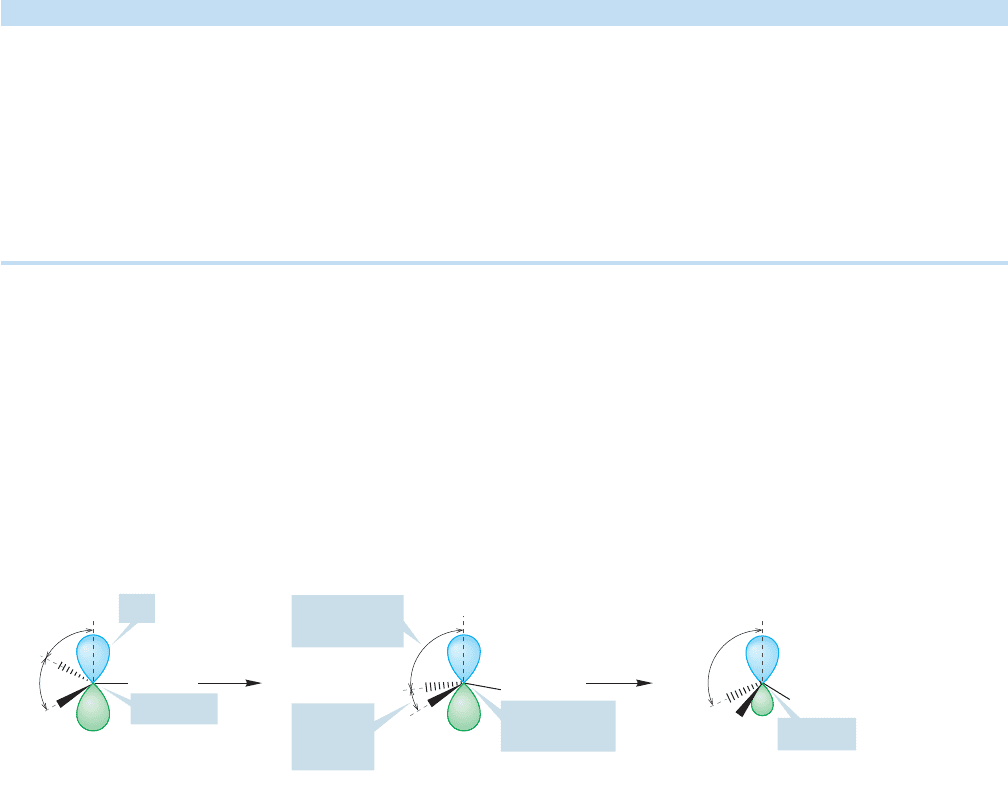

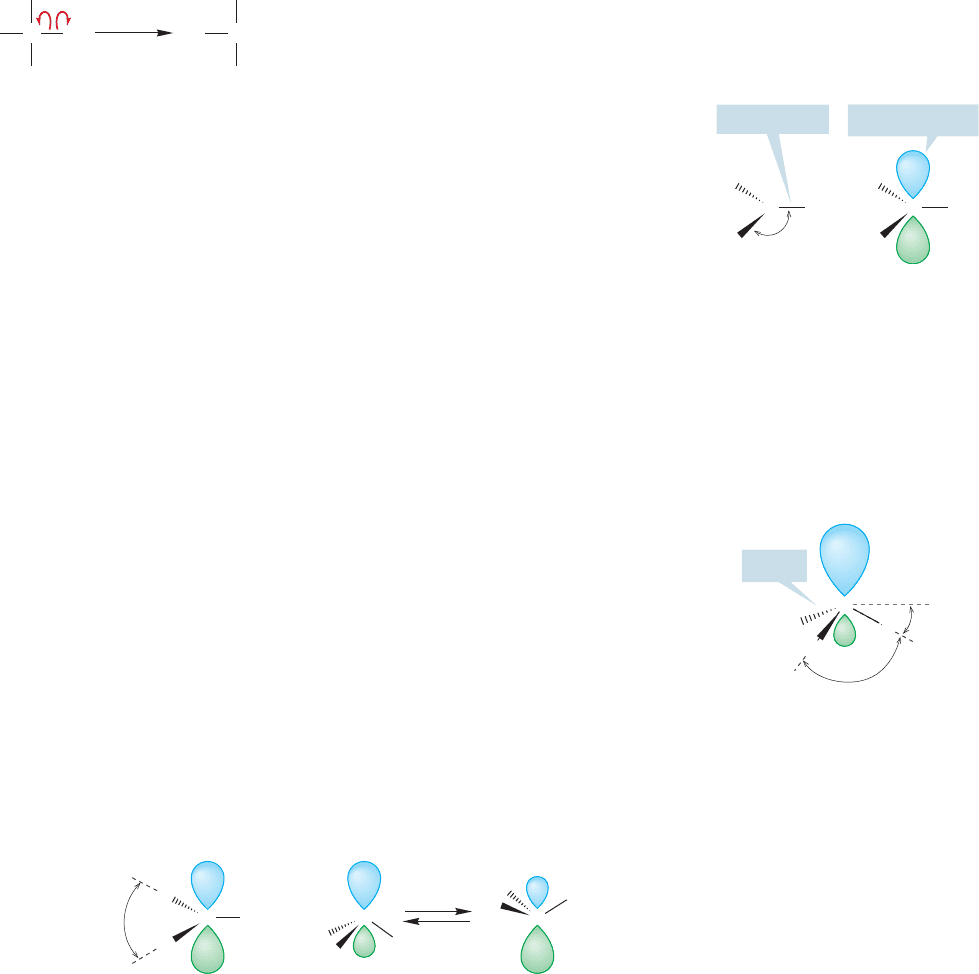

FIGURE 2.11 Formation of a bond from overlap of an sp

3

hybrid orbital of C with an s atomic orbital of X.

C

O

X

FIGURE 2.12 A thought experiment.The conversion of an sp

2

hybridized carbon into an sp

3

hybridized carbon.

What is the hybridization at a point intermediate between the starting point (sp

2

) and end point (sp

3

)?

2.3 The Methyl Group (CH

3

) and Methyl Compounds (CH

3

X) 61

The methyl is followed by the name of the X group as a separate word. Table 2.2

shows a number of methyl derivatives with their melting points, boiling points, and

physical appearances.

TABLE 2.2 Some Simple Derivatives of Methane, Otherwise Known as Methyl Compounds

Common Name mp (°C) bp (°C) Physical Properties

Methane 182.5 164 Colorless gas

Methyl alcohol or methanol 93.9 65.0 Colorless liquid

Methylamine 93.5 6.3 Colorless gas

Methyl bromide 93.6 3.6 Colorless gas/liquid

Methyl chloride 97.7 24.2 Colorless gas

Methyl cyanide or acetonitrile 45.7 81.6 Colorless liquid

Methyl fluoride 141.8 78.4 Colorless gas

Methyl iodide 66.5 42.4 Colorless liquid

Methyl mercaptan or methanethiol 123 6.2 Colorless gas/liquidH

3

C

O

SH

H

3

C

O

I

H

3

C

O

F

H

3

C

O

CN

H

3

C

O

Cl

H

3

C

O

Br

H

3

C

O

NH

2

H

3

C

O

OH

H

3

C

O

H

H

3

C

O

X

The bonding in methyl compounds closely resembles that in methane, and it is

conventional to speak of the carbon atom in any as being sp

3

hybridized,

just as it is in the more symmetrical CH

4

. Strictly speaking, this is wrong because

the bond from C to X is not the same length as that from C to H and the

bond angle cannot be exactly the same as the angle.

Because sp

3

hybridization yields four exactly equivalent bonds directed toward the

corners of a tetrahedron, the bonds to H and X in cannot be exactly sp

3

hybrids, only approximately sp

3

(sp

2.8

, say). This point is very often troubling to stu-

dents, but it is really quite simple and, once one has seen it, even obvious. Consider

converting an sp

2

hybridized carbon into an sp

3

hybridized carbon, as in Figure 2.12.

H

3

C

O

X

X

O

C

O

HH

O

C

O

H

H

3

C

O

X

120

90

109.5

2p

C is sp

2

C is sp

3

Pure sp

3

Pure sp

2

Between sp

2

and sp

3

Between

120 and

109.5

Between 90

and 109.5

C is between

sp

2

and sp

3

We start with the carbon having three sp

2

hybrid orbitals and a pure, unhybridized

2p orbital ( angle 120°). As we bend the sp

2

hybrid orbitals, we will

come to a point at which the angle has contracted to 109.5°, which is

sp

3

hybridization. Our orbitals, originally one-third s and two-thirds p (sp

2

: 33.3% s,

66.7% p character), have become one-fourth s and three-fourths p (sp

3

: 25% s, 75%

p character). They have gained p character in the transformation from sp

2

to sp

3

.Now look

at the 2p atomic orbital in Figure 2.12. As we bend, this orbital goes from pure p to

one-fourth s, three-fourths p. It has gained s character in the transformation.There is a

smooth transformation as we pyramidalize the orbitals from sp

2

to sp

3

, and between

these two extremes, the hybridization of carbon is intermediate between sp

2

and sp

3

,

something like sp

2.8

.The hybridizations sp

2

and sp

3

are limiting cases, applicable only

in completely symmetrical situations.The hybridization of a carbon (or other) atom

is intimately related to the bond angles! If you know one, you know the other.

H

O

C

O

H

H

O

C

O

H

62 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

In general,methyl compounds ( ) will closely resemble methane in their

approximately tetrahedral geometry; sp

3

is a good approximation, but methyl com-

pounds cannot be perfect tetrahedra.

In addition to CH

3

X, other substituted molecules are possible in which more

than one hydrogen is replaced by another atom or group of atoms. Thus, even for

one-carbon molecules, there are many possible substituted structures.

H

3

C

O

X

4

The name for carbocations was the focus of a long and too intense argument in the chemical community. A car-

bocation is sometimes called a carbonium ion by traditionalists or a carbenium ion by others. The compromise

carbocation is both aptly descriptive and avoids the emotional reactions of the staunch defenders of the other terms.

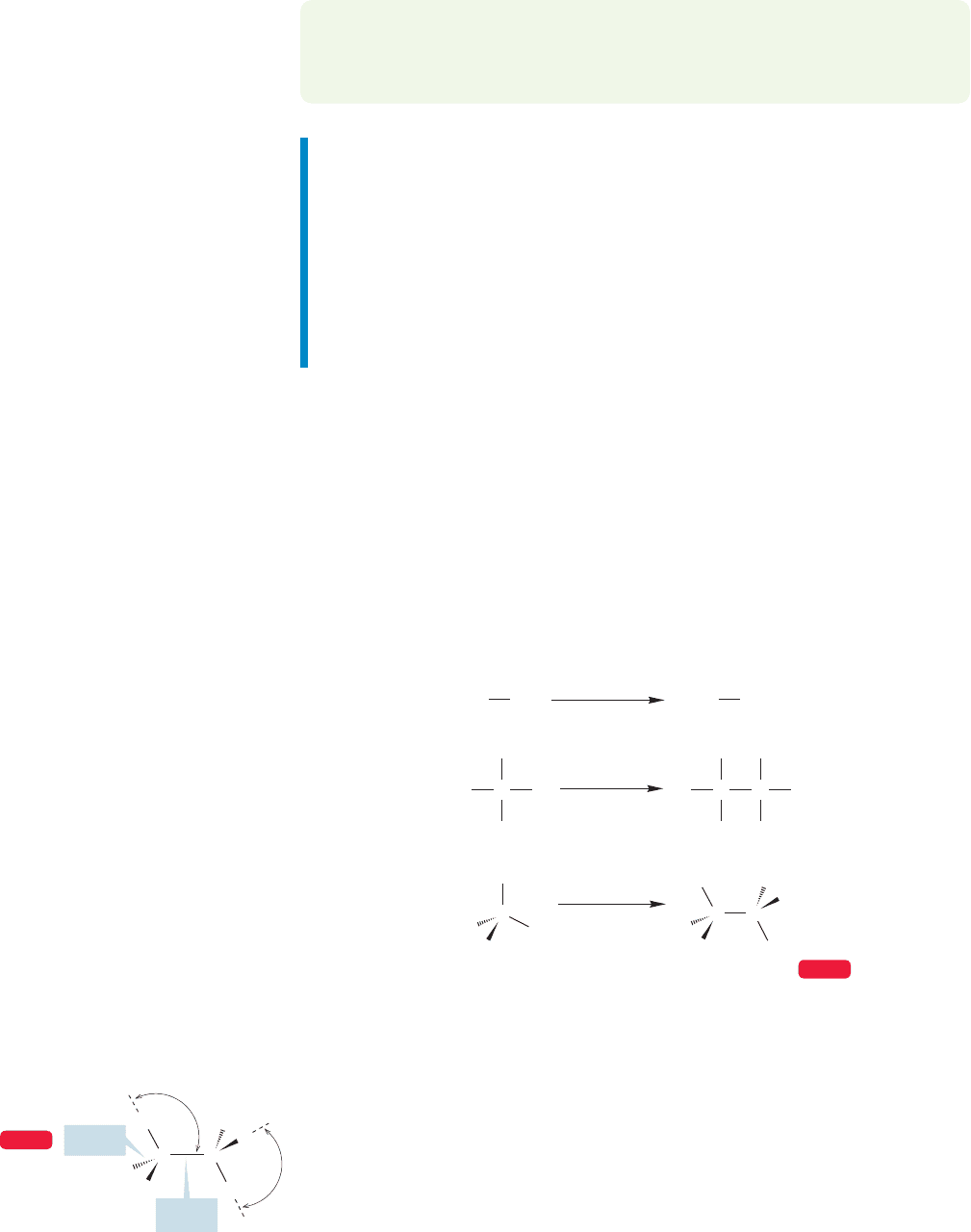

FIGURE 2.13 The formation of (a) the methyl cation (

CH

3

) and (b) the methyl anion (

CH

3

) by two

different heterolytic cleavages of a carbon–hydrogen bond in CH

4

.

:

..

..

..

(a) Carbocation formation

The methyl

cation

Hydride

(b) Carbanion formation

..

+

+

HH

H

H

C

HH

H

H

H

H

C

..

..

..

H

H

H

C

+

H

H

H

C

+

..

..

..

..

+

+

H

H

H

C

H

H

H

C

HH

+

H

+

H

H

H

H

H

..

..

..

..

C

..

C

–

–

The methyl

anion

A proton

–

H

..

H

–

..

PROBLEM 2.9 Use the halogens (X F, Cl, Br, or I) to draw all possible molecules

CH

2

X

2

. For example, CH

2

BrCl is one answer.

PROBLEM 2.10 Draw all possible molecules of the formula CH

2

X

2

, CHX

3

, and

CX

4

when X is F or Cl.

2.4 The Methyl Cation (

+

CH

3

), Anion (

ⴚ

CH

3

), and

Radical ( CH

3

)

Table 2.2 could be augmented to include

CH

3

,

CH

3

,and CH

3

,which are mem-

bers of a class of compounds called reactive intermediates.This name implies that

these molecules are too unstable to be isolable under normal conditions and must

usually be studied by indirect means, often by looking at what they did during their

brief lifetimes, or sometimes by isolating them at very low temperature.These three

species are especially important because they are prototypes—the simplest examples

of whole classes of molecules to be encountered later when the study of chemical

reactions takes over our attention.

We call

CH

3

a methyl cation. To make this molecule, one could imagine

removing a hydride (

H) from methane to produce

CH

3

.It is the simplest exam-

ple of a carbocation,a molecule containing a positively charged carbon

4

(Fig.2.13a).

Now imagine forming the methyl anion (

CH

3

) by removing a proton (H

)

from methane (Fig. 2.13b), leaving behind a pair of nonbonding or lone-pair elec-

trons in the negatively charged methyl anion.The resulting

CH

3

is a simple exam-

ple of a carbon-based anion, or carbanion.

:

:

:

.

:

.

:

2.4 The Methyl Cation (

+

CH

3

), Anion (

ⴚ

CH

3

), and Radical ( CH

3

) 63

.

:

Both of these ways of producing

CH

3

and

CH

3

involve the concept of breaking

a carbon–hydrogen bond in unsymmetrical fashion, a process known as heterolytic

bond cleavage (p. 37 and Fig. 2.13). Remember the curved arrow formalism—the

red arrows of Figure 2.13 move the pair of electrons in the carbon–hydrogen bond

to the hydrogen or to the carbon.

Recall from p. 37 that there is another way of breaking a two-electron bond, and

that is to allow one electron to go with each atom involved in the breaking bond

(Fig. 2.14). This homolytic bond cleavage in methane gives a hydrogen atom (H )

and leaves behind the neutral methyl radical (CH

3

). Note the single-barbed “fish-

hook” curved arrow convention is used to represent movement of one electron.

.

.

:

+

HH

H

H

C

H

H

H

H

.

.

C

A hydrogen

atom

The methyl

radical

FIGURE 2.14 The homolytic

cleavage of a carbon–hydrogen bond

in methane to give a hydrogen atom

and the methyl radical.

sp

2

/1s Bond

120⬚

+

Empty p orbital

H

C

H

H

+

H

C

H

H

FIGURE 2.15 The sp

2

hybridized

methyl cation,

CH

3

.The three bonds

shown are the result of overlap

between carbon’s sp

2

hybrid orbitals

and the 1s atomic orbital of each

hydrogen. The four atoms all lie in the

same plane, which is perpendicular to

the plane of the page.

–

1.10

H

C

21.4

107.5

..

H

H

A

FIGURE 2.16 The structure of the

methyl anion,

CH

3

.The

hybridization of the carbon in this

carbanion is approximately sp

3

.The

molecular shape is pyramidal.

:

sp

2

Two inverting shallow pyramids

H

H

H

or

C

120

.

H

H

H

C

.

H

H

H

C

.

FIGURE 2.17 The methyl radical

(CH

3

) is either planar or a rapidly

inverting shallow pyramid.The

carbon is close to sp

2

hybridized.

.

The methyl cation, anion, and radical have all been observed, although each

is extremely reactive, and thus, short-lived. They exist, though, and we can make

some predictions of structure for at least two of them. In the methyl cation

(

CH

3

), carbon is attached to three hydrogens, suggesting the need for three

hybrid atomic orbitals (recall BH

3

, p. 55), and therefore sp

2

hybridization

(Fig. 2.15).

Unlike the methyl cation, the carbon in the methyl anion is not only attached

to three hydrogens but also has a pair of nonbonding electrons. The cation has an

empty pure p orbital (zero s character) and therefore the species is as flat as a pan-

cake ( angle 120°). The methyl anion has two more electrons than

the cation and we have to consider them in arriving at a prediction of the anion’s

shape.Recall from Figure 1.7 that s orbitals have density at the nucleus. Because the

nucleus is positively charged and electrons are negatively charged, it is reasonable to

assume that an electron is more stable (lower in energy) in an orbital with a lot of

s character. A pyramidal structure seems appropriate for the methyl anion, although

of course it cannot be a perfect tetrahedron because this is a CH

3

X molecule (where

X is a lone pair of electrons).We can’t predict exactly how pyramidal the species will

be, and an anion’s shape is difficult to measure in any case, but recent calculations

predict the structure in Figure 2.16.

It is harder to predict the structure of the neutral methyl radical ( CH

3

),in which

there is only a single nonbonding electron. At present, it is not possible to choose

between a planar species and a rapidly inverting and very shallow pyramid,although

it is clear that the methyl radical is close to planar (Fig. 2.17). Do not be disturbed

by this! Chemists still do not know many seemingly simple things (such as the shape

and hybridization of the methyl radical). There is still lots to do!

.

H

O

C

O

H

64 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

PROBLEM 2.11 Draw a structure for the methyl radical at the halfway point for the

inversion shown in Figure 2.17. What is the hybridization of the carbon atom in

the structure you drew?

Summary

Methane can be substituted in many ways through replacement of one or more

hydrogens with another atom or groups of atoms. In principle,removal of a hydro-

gen from methane can lead to the methyl anion (

CH

3

), the methyl radical

(CH

3

), or the methyl cation (

CH

3

) depending on the nature of the hydrogen

removed (

H, H or

H). In this chapter, we have discussed only the shapes of

these intermediates—reactions are coming later. It will be important to remem-

ber that carbocations are flat and sp

2

hybridized and that simple carbanions are

pyramidal and approximately sp

3

hybridized.

:

.

.

:

2.5 Ethane (C

2

H

6

), Ethyl Compounds (C

2

H

5

X), and

Newman Projections

There is a special substituent X that produces a most interesting . In this

case, we let X CH

3

, another methyl group.Now becomes

which can also be written as C

2

H

6

. This molecule is ethane (Fig. 2.18), the second

member of the alkane family. You might try to anticipate the following discussion

by building a model of ethane and examining its structure now.

H

3

C

O

CH

3

H

3

C

O

X

H

3

C

O

X

(a)

CC

H

H

H

H

X

H

3

CH

3

CCH

3

(b)

Ethane (C

2

H

6

)

H

H

H

CX H

H

H

C

H

H

CH

(c)

X = CH

3

X = CH

3

X = CH

3

H

X

H

H

C

H

H

WEB 3D

FIGURE 2.18 The construction of

ethane ( ) by the

replacement of X in with a

methyl group.

H

3

C

O

X

H

3

C

O

CH

3

Even in a molecule as simple as ethane there are a number of inter-

esting structural questions. From the point of view of one carbon, the

attached methyl group takes up more room than the much smaller

hydrogens. So we expect the angle to be slightly larger

than the angle. And so it is: 111.0° and

109.3° (Fig. 2.19).

How are the hydrogens of one end of the molecule arranged with

respect to the hydrogens at the other end? There are two important struc-

tures for ethane, which are related by rotation about the bond.

Molecules that differ in spatial orientation as a result of rotation around a

C

O

C

H

O

C

O

H

H

O

C

O

CH

3

H

O

C

O

H

H

3

C

O

C

O

H

111.0

109.3

1.53

1.11

CC

H

H

H

H

H

H

A

A

WEB 3D

FIGURE 2.19 The detailed structure of ethane.

2.5 Ethane (C

2

H

6

), Ethyl Compounds (C

2

H

5

X), and Newman Projections 65

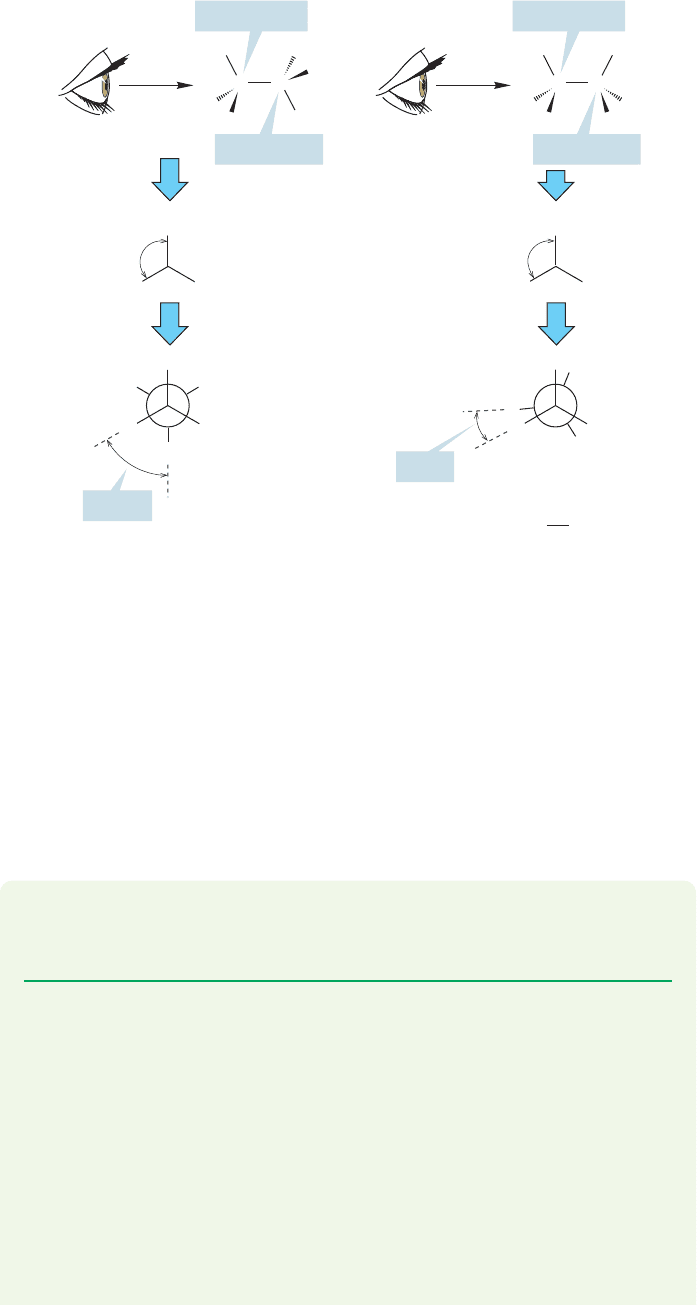

sigma bond are called conformations.The two important conformations for ethane

are eclipsed ethane and staggered ethane,each shown in a side view in Figure 2.20.

If one looks down the bond (Fig. 2.21) one can see that in the eclipsed con-

formation each of the three hydrogens on the front methyl eclipses a hydrogen on the

back methyl. In the staggered conformation, the view down the shows the

hydrogens in front arranged so that each hydrogen in back can be seen.When we look

down the bond,the angle between a hydrogen in front and a hydrogen in back

is called the dihedral angle.The dihedral angle is measured in degrees θ (pronounced

tha¯-ta). The dihedral angle between the hydrogens in the eclipsed ethane is 0°. The

dihedral angle in the staggered conformation is 60°. Ethane can exist in an infinite

number of conformations,depending on the value of the dihedral angle.We focus here

on the two extreme structures,eclipsed and staggered ethane. Be sure you see how these

two forms are interconverted by rotation about the carbon–carbon bond. Use a model!

A particularly effective way of viewing different conformations of a molecule is

called a Newman projection, after its inventor, Melvin S. Newman (1908–1993) of

Ohio State University. Like all devices, the Newman projection contains arbitrary

conventions that can only be learned, not reasoned out. Its utility will repay you for

the effort many times over, however, so do it! We first imagine looking down a par-

ticular bond, in this case the carbon–carbon bond in ethane. The three

carbon–hydrogen bonds attached to the front carbon are now drawn in as shown in

the middle row of Figure 2.21. Notice that from this end-on view the

angle on the front carbon is 120°.The rear carbon is next represented as a circle, and

the H atoms attached to it are put in as shown in the bottom row of Figure 2.21.

Constructing a Newman projection is easy for the staggered form (Fig. 2.21a)

but not so simple for the eclipsed molecule (Fig. 2.21b). If we were strictly accurate

in the drawing, we wouldn’t be able to see the hydrogens attached to the rear car-

bon of the eclipsed conformation because each is directly behind an H on the front

carbon (the dihedral angle is 0°). So we cheat a little and offset these eclipsed hydro-

gens just enough so we can see them.

Newman projections are extraordinarily useful in making three-dimensional

structures clear on a two-dimensional surface. For example, Figure 2.21a makes it

obvious that all six hydrogens in staggered ethane are the same—they are equiva-

lent in the language of organic chemistry.

H

O

C

O

H

C

O

C

C

O

C

C

O

C

rotation

Eclipsed ethane

The dihedral angle,

θ, is the angle between the red C H bonds

CC

H

H

H

H

H

H

Staggered ethane

CC

H

H

H

H

H

H

θ = 0

CC

H

H

H

H

H

H

θ = 60

H

CC

H

H

H

H

H

FIGURE 2.20 Two conformations of

ethane: the eclipsed and staggered

forms.

CONVENTION ALERT

PROBLEM 2.12 Write Newman projections for the staggered conformations of ethyl

chloride ( ) and 1,2-dichloroethane ( ).

In the second case, there are two staggered conformations of different energy. Can

you estimate which is more stable?

Cl

O

CH

2

O

CH

2

O

ClCH

3

O

CH

2

O

Cl

66 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

Which of the two limiting conformations of ethane represents the more stable

molecule? We would surely guess that it would be the staggered conformation, and

that guess would be exactly right. But the reason has little to do with the “obvious”

spatial requirement for the hydrogens.The hydrogens do not compete for the same

space in the eclipsed conformation. There may be some electrostatic repulsion

between the electrons in the bonds in the eclipsed bonds, but the eclipsed confor-

mation is mostly destabilized by the repulsive interaction of two filled orbitals in each

of the three pairs of eclipsed carbon–hydrogen bonds (Fig. 2.21b).

PROBLEM 2.13 Use an orbital interaction diagram like the one for He

2

in Figure

1.46, p. 40, to show the destabilization in eclipsed ethane. How many eclipsing

filled orbital–filled orbital interactions are present?

PROBLEM 2.14 There is a related orbital effect that stabilizes staggered ethane.Use an

orbital interaction diagram like the one for H

2

in Figure 1.47, p. 42, to show the sta-

bilization in staggered ethane. This problem is much harder than Problem 2.13, so

here is some help in the form of a set of tasks.The explanation that this problem leads

to was first pointed out to MJ by an undergraduate just like you about 25 years ago.

(a) Draw staggered ethane in a Newman projection.

(b) Draw the antibonding orbital for one of the bonds of the front carbon.

(c) Consider the bond that is directly behind the antibonding orbital

you have drawn. Can you see the overlap between the filled bonding orbital

in back and the empty antibonding orbital you drew?

C

O

H

C

O

H

C

H

H

H

H

H

H

(a) Staggered ethane

Rear carbon

Front carbon

(b) Eclipsed ethane

θ = 60⬚

θ = 0⬚

Notice how we must

cheat in this Newman

projection by offsetting

the rear C

H bonds

slightly; otherwise they

could not be seen

C

C

H

H

H

Rear carbon

Front carbon

C

H

H

H

HH

H

120⬚

HH

H

First draw the front carbon

with attached hydrogens; note

that the “C” is not drawn in

Now the rear carbon is

added as a circle; the

attached hydrogens are

drawn from the edge of

the circle

120⬚

H

H

H

HH

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

FIGURE 2.21 (a) A Newman

projection for staggered ethane.

The dihedral angle (θ) between two

carbon–hydrogen bonds is 60°.

(b) A Newman projection for

eclipsed ethane. The dihedral angle

(θ) between two carbon–hydrogen

bonds is 0°.

(continued)

2.5 Ethane (C

2

H

6

), Ethyl Compounds (C

2

H

5

X), and Newman Projections 67

(d) What factor stabilizes the staggered conformation of ethane over the

eclipsed conformation? How many interactions in the staggered conforma-

tion of ethane have overlap of bonding and antibonding orbitals?

If you can fight your way through this problem, you are in excellent shape in

terms of manipulating orbitals!

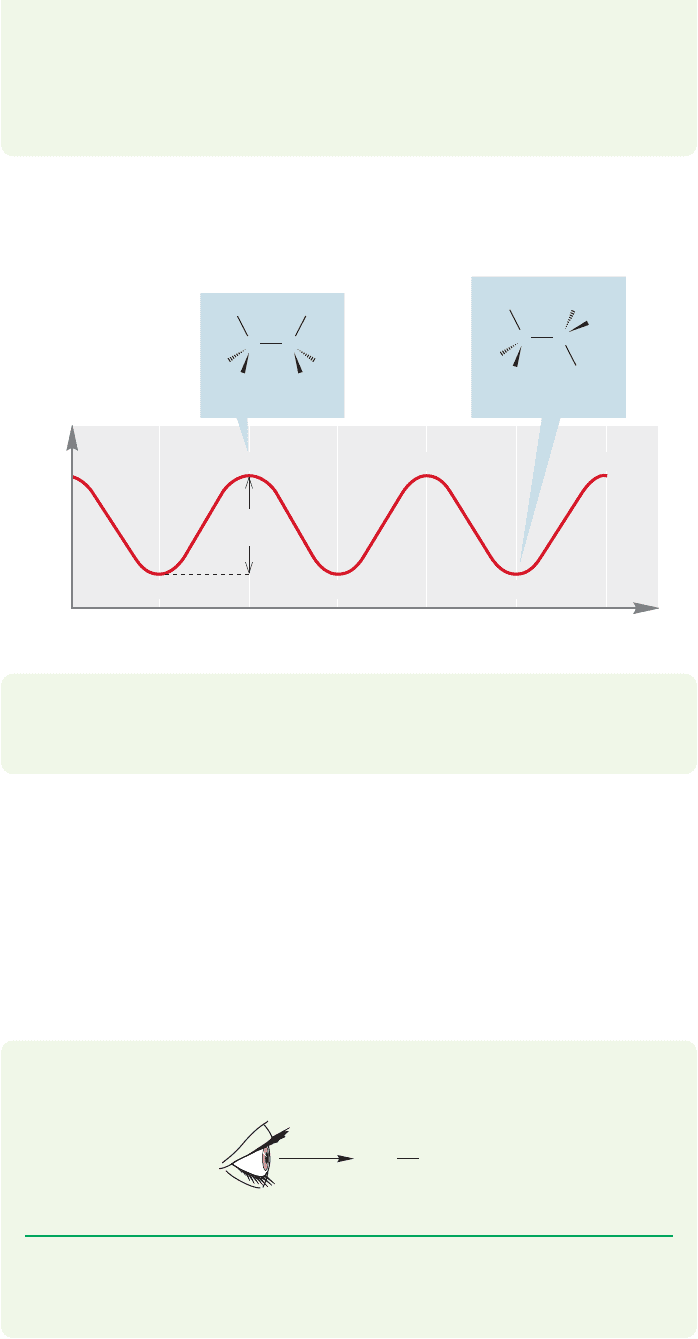

We can now make a plot of dihedral angle as a function of energy (Fig. 2.22).

Calculations show that the eclipsed form of ethane is an energy maximum, the top

of the energy barrier separating two staggered forms. Such a maximum-energy point

is called a transition state (TS).

PROBLEM 2.15 You recently saw a transition state, although the term wasn’t used.

Where? Hint: Where have we described two forms of a molecule that intercon-

vert by passing through another species? It is close by.

How big is the energy difference between the staggered and eclipsed conforma-

tions of ethane? This question asks how high the energy barrier is between two of the

minimum-energy staggered forms in Figure 2.22.The barrier turns out to be a small

number, 2.9 kcal/mol, an amount of energy easily available at room temperature. At

normal ambient temperatures,ethane is said to be freely rotating because there is ample

thermal energy to traverse the barrier separating any two staggered forms. On some

very cold planet, though, where there would be much less thermal energy available

than on Earth, alien organic chemists would have to worry more about this rotation-

al barrier. Thus, their lives would be even more complicated than ours.

Energy

Dihedral angle (θ)

0⬚ 60⬚ 120⬚ 180⬚ 240⬚ 300⬚ 360⬚

E

S S S

E E E

2.9

kcal/mol

H

H

H

C

C

H

H

H

Eclipsed ethane

H

H

H

C

H

H

H

C

Staggered ethane

FIGURE 2.22 A plot of the energy of

ethane as rotation around the

carbon–carbon bond occurs.

CH

2

OH

Eye

H

3

C

PROBLEM 2.16 Draw the low-energy Newman projection for the structure depicted

below by looking down the carbon–carbon bond.

PROBLEM 2.17 Imagine 1,2-dideuterioethane ( ), where D deu-

terium, on some cold planet such as Pluto. If there were not enough energy available

to overcome the barrier to rotation,how many 1,2-dideuterioethanes would there be?

DCH

2

O

CH

2

D

68 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

The chemical and physical properties of ethane closely resemble those of

methane. Both are gases at room temperature, and both are quite unreactive under

most chemical conditions. But not all conditions! One need only light a match in a

room containing either ethane or methane and air to find that out.This reaction is

actually very interesting. If we examine the debris after the explosion, we find two

new molecules, water and carbon dioxide:

2 H

3

C CH

3

7 O

2

4 CO

2

+ 6 H

2

O + and

Ethane

match

Heat Ligh

t

A thermochemical analysis indicates that water and carbon dioxide are more sta-

ble than ethane and oxygen. Presumably, this is the reason ethane explodes when

the match is lit. Energy is all too obviously given off as heat and light. But why do

objects that are stable in air, such as ethane or wood, explode or burn continuously

when ignited? How are they protected until the match is lit?

We’ll approach these questions in Chapter 8, but

it’s worth some thought now in anticipation. This

matter is serious because the molecules in our bod-

ies are also less thermodynamically stable than their

various oxidized forms,and we live in an atmosphere

that contains about 20% oxygen. Why can humans

live in such an atmosphere without spontaneously

bursting into flame? This issue has been of some con-

cern, and not only for scientists.

5

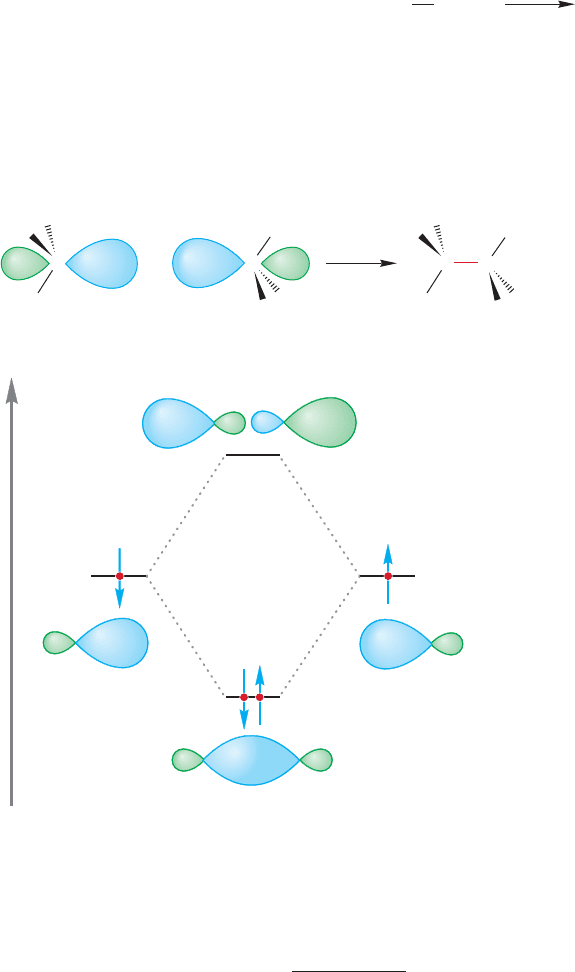

We can imagine making ethane by allowing two

methyl radicals to come together (Fig.2.23).The two

sp

3

hybrid orbitals, one on each carbon, overlap to

form a new carbon–carbon bond.This orbital overlap

produces a bonding molecular orbital, which is a σ

orbital because of its cylindrical symmetry. Of course,

the process simultaneously creates an antibonding

molecular orbital (σ*). The bonding orbital is filled

by the two electrons originally in the two methyl rad-

icals and the antibonding orbital is empty.We might

guess that the overlap of the two equal-energy sp

3

hybrid orbitals would be very favorable,and it is.The

carbon–carbon bond in ethane has a strength of

about 90 kcal/mol.This value is the amount of ener-

gy by which ethane is stabilized relative to a pair of

separated methyl radicals and is therefore the amount of energy required to break

this strong carbon–carbon bond.The formation of ethane from two methyl radicals

is exothermic by 90 kcal/mol:

ΔH ° 90 kcal/molCH

3

U

H

3

C

O

CH

3

.

+

.

H

3

C

5

Eliot ...claimed to be deeply touched by the idea of an inhabited planet with an atmosphere that was eager

to combine violently with almost everything the inhabitants held dear ...“When you think of it, boys,” he

said brokenly, “that’s what holds us together more than anything else, except maybe gravity. We few, we happy

few, we band of brothers—joined in the serious business of keeping our food, shelter, clothing and loved ones

from combining with oxygen.”

—Kurt Vonnegut,

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

H

H

H

H

H

H

C

H

H

H

C

C

H

H

H

C

Energy

+

.

.

.

.

Two methyl radicals Ethane

CH

3

.

H

3

C

.

The bonding

molecular orbital,

σ

sp

3

sp

3

sp

3

+ sp

3

sp

3

– sp

3

The antibonding

molecular orbital,

σ∗

FIGURE 2.23 An orbital interaction

diagram for the formation of ethane

through the combination of a pair of

methyl radicals.