Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

2.10 The Naming Conventions for Alkanes 79

In general, the stem of the name tells you the number of carbon atoms (meth 1,

eth 2, prop 3, but 4, and so on), and the suffix “ane” tells you that the mol-

ecule is an alkane. The alkane name is sometimes called the root word. The names

of some straight-chain alkanes are collected in Table 2.4.

TABLE 2.4 Some Straight-Chain Alkanes

Name Formula mp (°C) bp (°C)

Methane CH

4

182.5 164

Ethane CH

3

CH

3

183.3 88.6

Propane CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

189.7 43.1

Butane CH

3

(CH

2

)

2

CH

3

138.4 0.5

Pentane CH

3

(CH

2

)

3

CH

3

129.7 36.1

Hexane CH

3

(CH

2

)

4

CH

3

95 69

Heptane CH

3

(CH

2

)

5

CH

3

90.6 98.4

Octane CH

3

(CH

2

)

6

CH

3

56.8 125.7

Nonane CH

3

(CH

2

)

7

CH

3

51 150.8

Decane CH

3

(CH

2

)

8

CH

3

29.7 174.1

Undecane CH

3

(CH

2

)

9

CH

3

25.6 195.9

Dodecane CH

3

(CH

2

)

10

CH

3

9.6 216.3

Eicosane CH

3

(CH

2

)

18

CH

3

36.8 343.0

Triacontane CH

3

(CH

2

)

28

CH

3

66 449.7

Pentacontane CH

3

(CH

2

)

48

CH

3

92

It will be important to know how to interpret the IUPAC names, because this

skill is part of learning the language of organic chemistry. This ability also will help

you understand the contents listed on your cereal boxes and shampoo bottles. Here

are the most important rules of the IUPAC naming convention for alkanes and sub-

stituted alkanes:

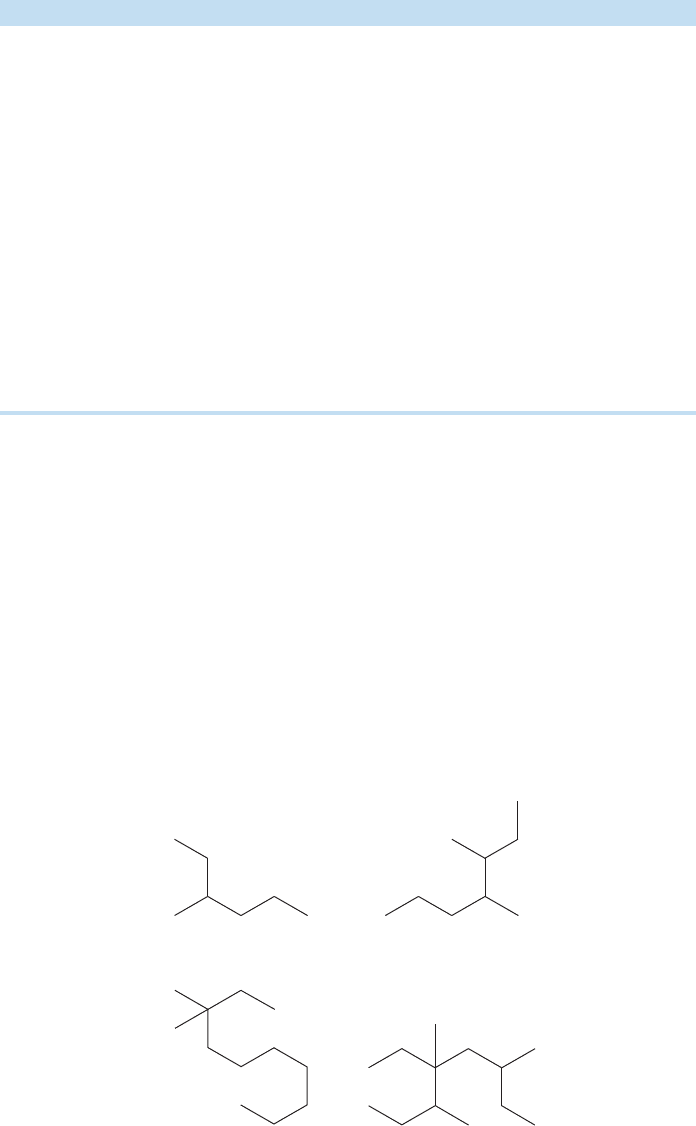

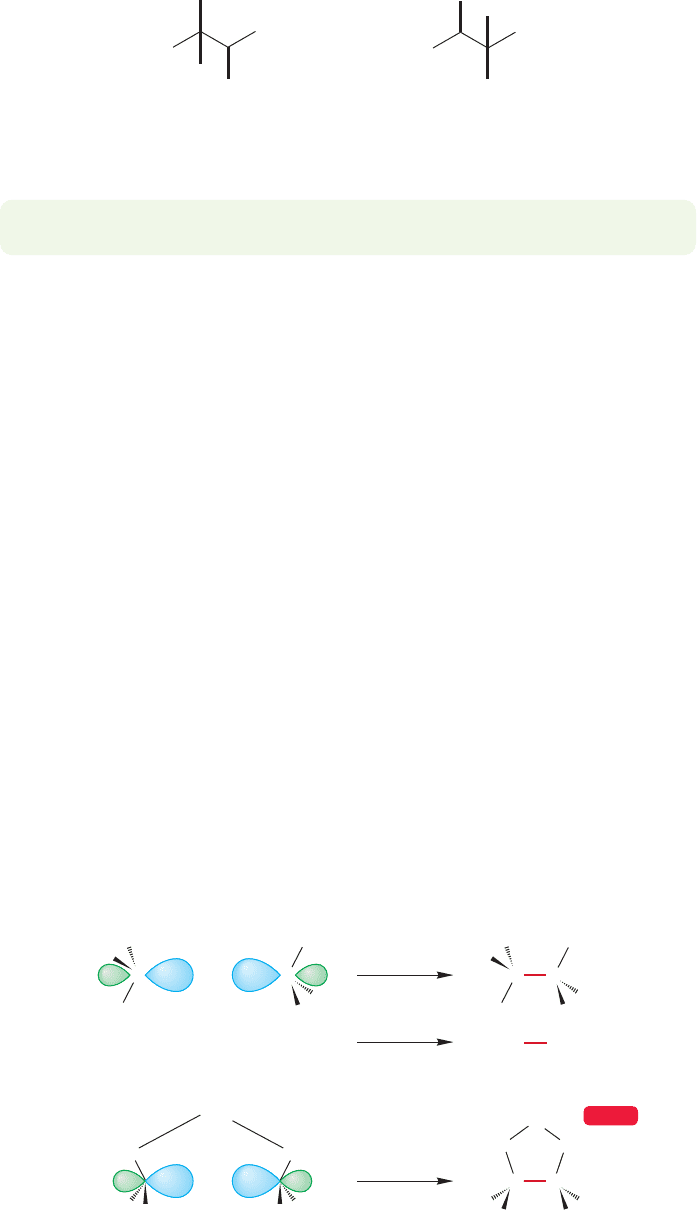

1. Find the longest chain of continuously connected carbons. Choose the root word

that matches that chain length (see Table 2.4). The compound is named as a deriv-

ative of this parent hydrocarbon. Finding the longest chain can be a bit tricky at first

because the angled, two-dimensional line drawings are not always drawn in a con-

venient horizontal line. The horizontal part of the drawing may not be the longest

chain. In the examples in Figure 2.39 it is perfectly reasonable to count in any pos-

sible way in order to find the longest chain.

A substituted hexane A substituted heptane

A substituted decane A substituted octane

FIGURE 2.39 Finding the longest

straight chain of carbons in alkanes.

80 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

2. In a substituted alkane, the substituent is given a number based on its position in

the parent hydrocarbon. The longest chain is numbered so as to make the number

of the substituent position as low as possible.The substituent is listed as a prefix to

the root word, with the number indicating its location on the chain. Some exam-

ples are shown in Figure 2.40. In a polysubstituted alkane, all the substituents

receive numbers. The longest chain is numbered so that the lowest possible num-

bers are used. A useful trick is to number the chain from the end closest to the first

substituent or branch point.

2-Chlorobutane

1

24

3

3-Fluorohexane

1

24

3

5

6

not 4-Fluorohexane

6

53

4

2

1

not 3-Chlorobutane

4

31

2

Cl Cl

F

F

FIGURE 2.40 Number the chain so as

to produce the smallest number for a

substituent.

3. When there are multiple substituents, they are always ordered alphabetically in the

prefix (Fig. 2.41). If the multiple substituents are identical, then di-, tri-, tetra-, and

4

3

1

2

Cl

2-Chloro-3-fluorobutane

n

ot 3-chloro-2-fluorobutane

n

ot 2-fluoro-3-chlorobutane

4

5

3

1

2

6

Br

3-Bromo-4-methylhexane

not 4-bromo-3-methylhexane

not 3-methyl-4-bromohexane

4

5

37

1

2

6

8

Cl

C(CH

3

)

3

4-tert-Butyl-5-chlorooctane

not 4-chloro-5-tert-butyloctane

F

FIGURE 2.41 Nonidentical substituents are incorporated into the name alphabetically.

so on are used as prefixes to the substituent name (Fig. 2.42). The modifiers di-, tri-,

tetra-, and so on are ignored in determining alphabetical order. Use of the common

names for substituents is not strictly proper, but you might encounter it. In such

cases the sec- and tert- are ignored in determining alphabetical order, but the iso-

and neo- are used. Thus, tert-butyl would appear in the name earlier than chloro,

and isopropyl would come before methyl.

2,3-Dimethylbutane 2,3,4 -Trichloropentane

1

2

4

3

4

53

1

2

1,1,1,5,5,5-Hexafluoropentane

3

15

42

Cl Cl

Cl

F

F

F

F

F

F

FIGURE 2.42 When the substituents

in a polysubstituted alkane are the

same, prefixes di-, tri-, and so on tell

you the number of the multiple

substituents.

2.10 The Naming Conventions for Alkanes 81

4. When rules 1 through 3 do not resolve the issue,the name that starts with the lower

number is used, as demonstrated in Figure 2.43. This rule is sometimes referred to

as the alphabetical preference rule. If both numbering choices on the alkane use the

same numbers, then the preference is given to the alphabet.

2-Bromo-6-methylheptane

n

ot 6-bromo-2-methylheptane

Br

FIGURE 2.43 In unresolvable cases,

start with the lowest possible number.

The carbon chain is numbered from

the end that gives the first-named

substituent the lower number.

PROBLEM 2.25 Write systematic names for the following compounds:

(a) (b) (c)

(e) (f)

(d)

Br

Br

F

Cl

PROBLEM 2.26 Write structures for the following compounds: (a) 2-bromobutane,

(b) decane,(c) tert-butyl chloride,(d) 1,4-difluoropentane,(e) 2,4,4-trimethylheptane.

Although the instruction to name substituents on alkanes in alphabetical order

looks simple,the process is a bit complex because some modifiers count in the alpha-

bet and others do not. Table 2.5 contains a brief summary.

TABLE 2.5 Some Common Prefixes

Prefix Use Counts in Alphabetical Order?

di- Any two identical groups No

tri- Any three identical groups No

tetra- Any four identical groups No

iso Isopropyl Ye s

neo Neopentyl Ye s

sec- sec-Butyl No

tert- tert-Butyl No(CH

3

)

3

C

O

CH

3

CH

2

CH(CH

3

)

O

(CH

3

)

3

CCH

2

O

(CH

3

)

2

CH

O

PROBLEM 2.27 Use the information in Table 2.5 to name the following two

compounds:

82 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

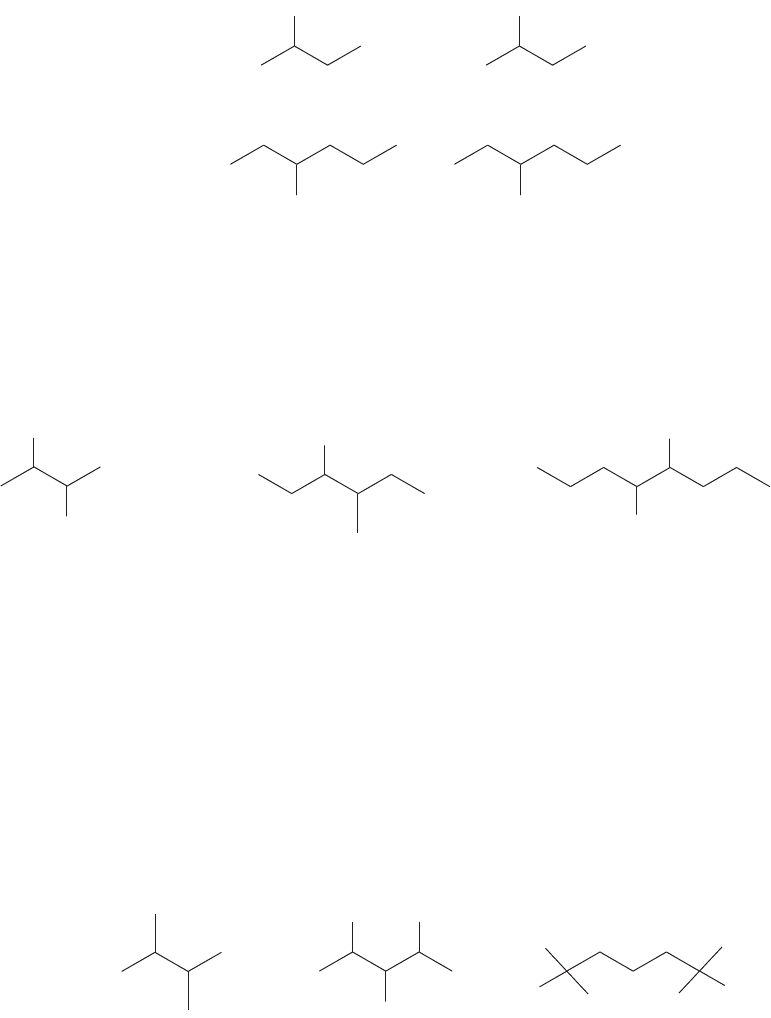

2.11 Drawing Isomers

A common question on organic chemistry tests is, Write all the isomers of pentane

(or hexane, or heptane, etc.). Such problems force us to cope with the translation of

two-dimensional representations into three-dimensional reality. Figuring out the

pentanes is easy; there are only three isomers.Even writing the hexane isomers (there

are five) or isomers of heptane (there are nine) is not really difficult. But getting all

18 isomers of octane is a tougher proposition, and getting all 35 isomers of nonane

with no repeats is a real challenge.

Success depends on finding a systematic way to write isomers. Thrashing

around writing structures without a system is doomed to failure. You will not get

all the isomers and there is a high probability of generating repeat structures.

Any system will work as long as it is truly systematic. One possibility is shown in

the following Problem Solving box, which generates the nine isomers of heptane

shown in Figures 2.44–2.47.

Heptane

Both still heptane!

Common repeats:

FIGURE 2.44 Heptane.

Common repeats

Hexanes—

one C atom must

be added as a branch

2-Methylhexane

3-Methylhexane

Still 3-methylhexane

Still 3-methylhexane

FIGURE 2.45 Methylhexanes.

Common repeatCommon repeat

Pentanes—

two C atoms must be added as branches

2,3-Dimethylpentane

Still 2,3-dimethylpentane Still 2,3-dimethylpentane

2,2-Dimethylpentane 2,4-Dimethylpentane 3,3-Dimethylpentane 3-Ethylpentane

FIGURE 2.46 3-Ethylpentane and the

dimethylpentanes.

PROBLEM SOLVING

Draw all the isomers having the molecular formula C

7

H

16

.

1. Start by drawing the longest unbranched carbon chain possible, which is

heptane in this case (Fig. 2.44).

2. Shorten the chain by one carbon, and add the “extra” carbon as a methyl

group at all possible positions, starting at the left and moving to the right

(Fig. 2.45). Note that you can’t add this carbon to the end of the chain

because doing that would just regenerate heptane. You have to start the

addition process one carbon in from the end. This step generates all the

methylhexanes. You must check each isomer you make to be sure it is not a

repeat. One way to be absolutely certain is to name each molecule as you

generate it. If you repeat a name, you have repeated an isomer.

3. Shorten the chain by one more carbon. The longest straight chain is now

five carbons. Two carbons are to be added as two methyl groups or as a sin-

gle ethyl group (Fig. 2.46). Two methyl groups can be placed either on the

same carbon or on different carbons. Again, start at the carbon one in from

the left end of the chain and move to the right, checking each isomer you

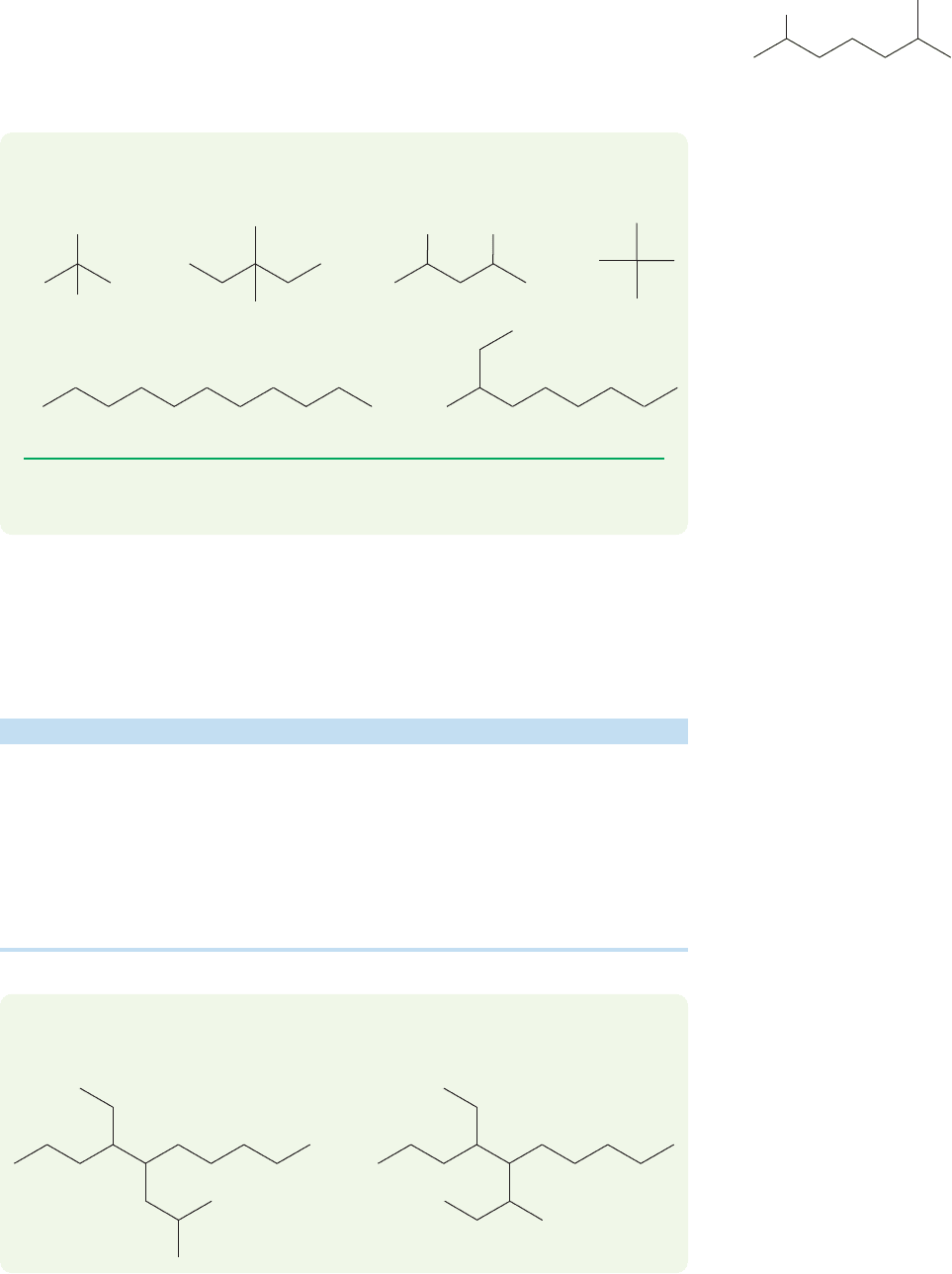

create by naming it to be sure it is not a repeat.

4. Shorten the chain by one carbon again, and try to fit the three “extra”

carbons on a butane chain. There is only one way to do this (Fig. 2.47).

2.12 Rings 83

Common repeat

Butane—

Three C atoms

must be added as branches

2,2,3-Trimethylbutane

Still 2,2,3-trimethylbutane

FIGURE 2.47 Trimethylbutane.

PROBLEM 2.28 Write and name all the isomers of octane, C

8

H

18

.

2.12 Rings

All the hydrocarbons we have met so far have the molecular formula C

n

H

2n 2

.

Because these molecules are linear or branched chains, we refer to them as either

noncyclic or acyclic alkanes.Molecules of this formula are also called saturated hydro-

carbons, which means that the carbon–carbon bonds in the molecule are all single

bonds.There is a class of closely related molecules that shares most chemical prop-

erties with the noncyclic alkanes but not the general formula.These molecules have

the composition C

n

H

2n

and are the cycloalkane ring compounds mentioned briefly

in Section 2.1. Cycloalkanes with this formula are also saturated.Molecules that have

the formula C

n

H

2n

but have no rings are called unsaturated hydrocarbons.

Unsaturated compounds have carbon–carbon double (or triple) bonds and will be

discussed in Chapter 3.

What might the bonding in cyclic molecules be? It probably will not deviate

much from what we already know because the chemical properties of cycloalkanes

resemble very closely those of the noncyclic alkanes.There is no essential difference

between the process used to make ethane from two methyl radicals (Fig. 2.48a) and

this construction of a ring compound (Fig. 2.48b). Nor would we expect to see big

differences in chemical properties, because the bonding in pentane is not signifi-

cantly different from that in cyclopentane.

(a)

H

3

C

H

2

C

CH

3

Two methyl radicals Ethane

H

H

H

CH

2

CH

2

C

H

C

.

.

.

H

3

CCH

3

Cyclopentane

.

H

H

H

H

H

H

CC

H

H

+

+

(b)

.

.

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

+

CH

2

CC

CH

2

H

2

C

WEB 3D

FIGURE 2.48 (a) The formation of

ethane through the overlap of two

singly occupied sp

3

hybrid orbitals.

(b) The closely related formation of a

ring compound, cyclopentane,

through the overlap of two singly

occupied sp

3

hybrid orbitals.

84 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

Cycloalkanes are named by attaching the prefix cyclo- to the name of the

parent hydrocarbon (Table 2.6).

TABLE 2.6 Some Cyclic Alkanes (Cycloalkanes)

Name Formula mp (°C) bp (°C, 760 mmHg)

Cyclopropane (CH

2

)

3

127.6 32.7

Cyclobutane (CH

2

)

4

90 12

Cyclopentane (CH

2

)

5

93.9 49.2

Cyclohexane (CH

2

)

6

6.5 80.7

Cycloheptane (CH

2

)

7

12 118.5

Cyclooctane (CH

2

)

8

14.3 148–149 (749 mmHg)

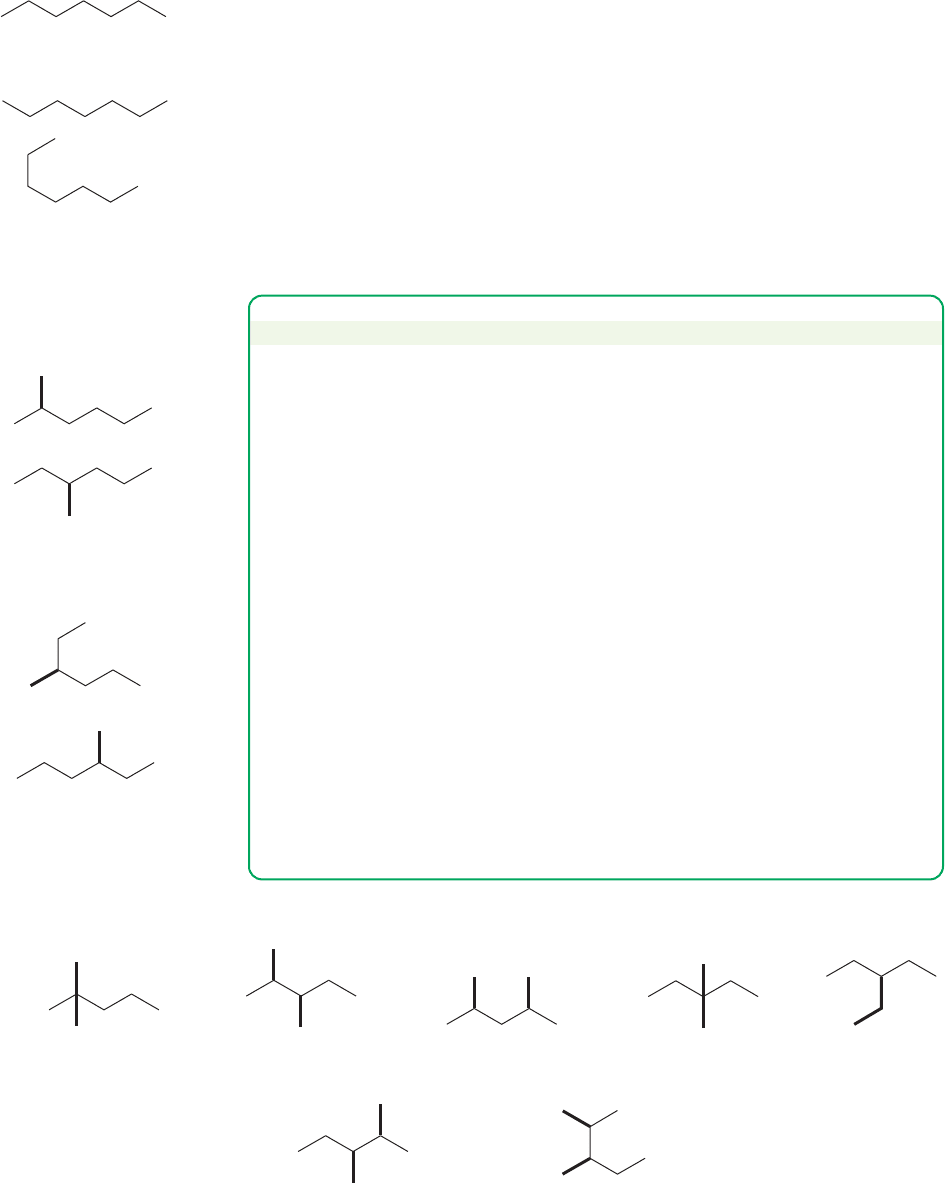

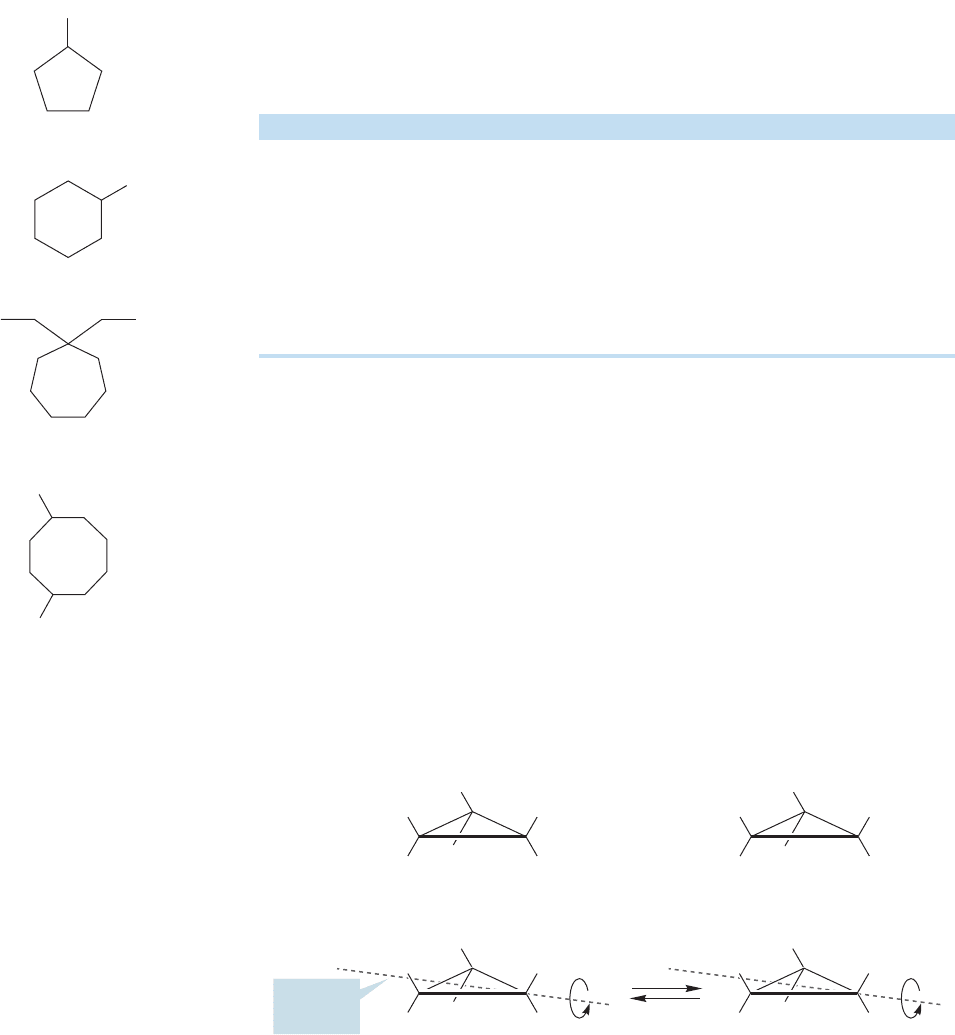

Monosubstituted cycloalkanes require no numbers for naming. In polysubstituted

ring compounds, substituents are assigned numbered positions, and the ring atoms

are numbered so that the lowest possible numbers are used. Multiple substituents

are named in alphabetical order in the prefix (Fig. 2.49). Prefix modifiers (di-, tri-,

etc.) are dealt with as shown in Table 2.5.

There is one important new structural feature that appears in cycloalkanes.There

is only a single methylcyclopropane, which is why there is no number used in nam-

ing it. But there are two isomers of 1,2-dimethylcyclopropane. As shown in Figure

2.50, there is no “sidedness” to methylcyclopropane. The molecule with the methyl

group “up” can be transformed into the molecule with the methyl group “down” by

rotating the molecule 180° about the axis shown in Figure 2.50, in other words, by

simply turning the molecule over.

Methylcyclopentane

Chlorocyclohexane

1,1-Diethylcycloheptane

1-Fluoro-4-iodocyclooctane

n

ot 4-iodo-1-fluorocyclooctan

e

or 4-fluoro-1-iodoc

y

clooctane

Cl

CH

3

F

I

FIGURE 2.49 Cycloalkanes are named

and numbered in a fashion similar to

the system for acyclic alkanes.

Rotation

axis

CH

3

H

=

H

H

H

Rotate 180⬚

H

CH

3

H

H

H

H

H

CH

3

HH

H

H

H

H

CH

3

H

H

H

H

FIGURE 2.50 There is only one

isomer of methylcyclopropane.The

thicker line in these drawings is used

to show the side of the cyclopropane

nearest to you.

However, no number of translational or rotational operations can change the 1,2-

dimethylcyclopropane with both methyl groups on the same side of the ring, called

cis, into the 1,2-dimethylcyclopropane with the methyl groups on opposite sides,

called trans (Fig. 2.51). The two molecules are certainly different from each other.

The use of models is absolutely mandatory at this point. Make models of these two

compounds and convince yourself that nothing short of breaking carbon–carbon

bonds will allow you to turn cis-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane into the isomeric trans-

1,2-dimethylcyclopropane.

2.12 Rings 85

PROBLEM 2.29 1,2-Dimethylcyclopropane is even more complicated than just

described, as you will see in Chapter 4,because there are two isomers of trans-1,2-

dimethylcyclopropane! Use your models to construct the mirror image of the

trans-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane you just made and see if it is identical to your

first molecule.

CH

3

H

3

C

HH

H

H

Methyl groups on

the same side

cis-1,2-Dimethylcyclopropane

WEB 3D

H

3

C

CH

3

H

H

H

H

Methyl groups on

opposite sides

trans-1,2-Dimethylcyclopropane

WEB 3D

FIGURE 2.51 Two isomers of

1,2-dimethylcyclopropane.

Cyclic compounds are extremely common. Both small and large varieties are

found in Nature, and many kinds of exotic cyclic molecules not yet found outside

the laboratory have been made by chemists. Moreover, ring molecules can be com-

bined in a number of ways to form polycyclic molecules. Here is an opportunity for

you to think ahead.How might two rings be attached to each other? Some ways are

obvious, but others require some thought.We will work through this topic as a series

of four problems, two worked in the chapter, two not. A number of different struc-

tural types can be created from two rings.These problems lead you through them.

WORKED PROBLEM 2.30 Draw a molecule that has the formula C

10

H

18

and is

composed of two five-membered rings.

ANSWER Two five-membered rings can be joined in a very simple way to make

bicyclopentyl. There is no real difference between this process and the formation

of ethane from two methyl radicals (p. 68).

Cyclopentane

(C

5

H

10

)

Cyclopentyl

(C

5

H

9

)

Bicyclopentyl

(C

10

H

18

)

H

H

H

.

C

9

H

16

The two rin

g

s share one carbon

CCC

H

H

HH

WORKED PROBLEM 2.31 Another molecule containing two five-membered rings

has the formula C

9

H

16

.Clearly,we are not dealing with a simple combination of two

cyclopentanes here because we are short one carbon—it’s C

9

, not C

10

, as in bicy-

clopentyl. The two rings must share one carbon somehow. Draw this compound.

ANSWER The way to have two rings sharing a carbon is to let one carbon be part

of both rings:

PROBLEM 2.32 Two five-membered rings can share more than one carbon. Two

similar molecules that are structured this way both have the formula C

8

H

14

.Draw

them. Hint: Focus on the two shared carbons and the hydrogens attached to them.

(Make a model.) That’s all the help you get here. Use Problem 2.31 as a guide.

PROBLEM 2.33 Finally, and most difficult, there is a molecule, still constructed

from five-membered rings, that has the formula C

7

H

12

. In this molecule, the two

five-membered rings must share three carbons. Draw this molecule.

86 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

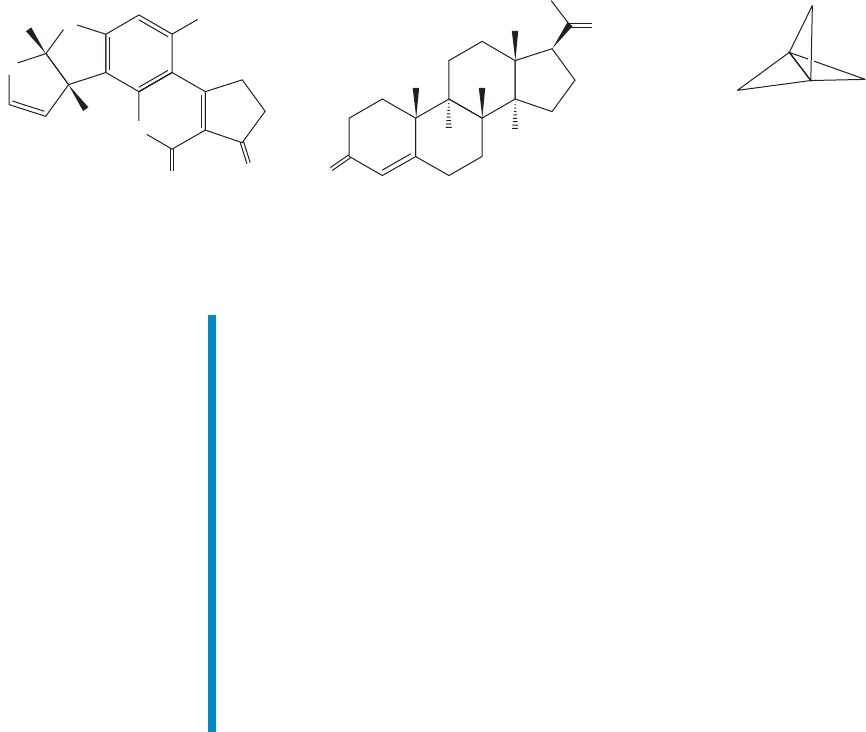

Polycyclic compounds can be exceedingly complex. Indeed, much of the fasci-

nation that organic chemistry holds for some people is captured nicely by the beau-

tifully architectural structures of these compounds. Figure 2.52 shows three examples

of cyclic molecules. Aflatoxin B

1

and progesterone are found in Nature and we will

refer to such compounds as natural products. The compound [1.1.1]propellane is

not (yet) found outside the laboratory. Aflatoxin B

1

is a highly toxic fungal metabo-

lite. Progesterone is one of a class of molecules called steroids; it has an antiovula-

tory effect if taken during the middle days of the menstrual cycle.

Aflatoxin B

1

made in 1966 by G. Büchi

and his research group at MIT

[

1.1.1

]

Propellane

made in 1982 by K. B. Wiberg

and his group at Yale; this

molecule was also made

slightly later in a particularly

simple way by the group of

G. Szeimies at Munich

Progesterone

made in 1967 by G. Stork and his

group at Columbia University

O

O

H

H

O

O

H

O

O

O

OCH

3

CH

3

CH

3

H

3

C

H

H

FIGURE 2.52 Some polycyclic

molecules.

Summary

To name alkanes:

1. Find the longest chain and use the appropriate root word.

2. Number the chain to give the lowest possible numbers for the substituents.

3. Arrange the substituents in the prefix alphabetically, and include the carbon

number for each to describe its location.

Drawing isomers requires finding a system that allows you to consider all the

possible perturbations. One approach is to start with the longest possible chain

and then reduce the chain length one carbon at a time, considering the possible

locations of the displaced methyl group with each reduction.

Cycloalkanes are bonded in the same way as noncyclic alkane molecules—by

overlap of sp

3

hybrid orbitals. Ring compounds have sides, which means that

substituents can be on the same side (cis) or on opposite sides (trans). All man-

ner of polycyclic molecules (two or more rings) exist.

2.13 Physical Properties of Alkanes and Cycloalkanes

At room temperature and atmospheric pressure, simple saturated hydrocarbons and

cycloalkanes are colorless gases, clear liquids, or white solids, depending on their

molecular weight. To many people, they smell bad, although some of us think that

these molecules have been the victims of a bad press and don’t smell bad at all.

Cooking gas, which is mostly saturated hydrocarbons, has an odor that comes from

a mercaptan (RSH) (Remember: R stands for a general alkyl group, p. 69), put in

specifically so that escaping gas can be detected by smell.

Tables 2.4 and 2.6 show some physical properties of straight-chain and cyclic

alkanes. Why do the boiling points increase as the number of carbons in the

2.13 Physical Properties of Alkanes and Cycloalkanes 87

molecule increases? The boiling point is a measure of the ease of breaking up

intermolecular attractive forces.There is a factor that stabilizes the liquid phases of

hydrocarbons called van der Waals forces (Johannes Diderik van der Waals,

1837–1923). When two clouds of electrons approach each other, dipoles (molecules

with two poles, p. 14) are induced as the clouds polarize in such a fashion as to

stabilize each other by opposing plus and minus charges (Fig. 2.53).

Highly symmetrical neopentane has

a nearly spherical cloud of electrons

(bp 9.5 ⬚C; mp –16.5 ⬚C)

The more extended molecule pentane

has a much greater surface area and has

greater intermolecular interactions

(bp 36.1 ⬚C; mp –130 ⬚C)

Minimal interaction between two

spheres allows for relatively weak

van der Waals forces

More extensive contact possible in the

extended molecule allows more powerful

van der Waals interactions

δ– δ+ δ– δ+

δ– δ+ δ–

δ+ δ+ δ–

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

H

3

C

CH

3

CH

3

H

3

C

H

3

C

C

Separated molecules

(gas phase)

Aggregated molecules

(solution) held together

by opposite charges

Attraction between

induced opposite

charges in

liquid phase

δ–

δ+

δ–

δ+

δ–

δ+

FIGURE 2.53 The stabilization of

molecules through van der Waals

forces.

Of course, many alkanes have small dipoles to begin with, but they are very small

and do not serve to hold the molecules together strongly. So alkanes have relatively

low boiling points. Other molecules are much more polar, and this polarity makes a

big difference in boiling point.Polar molecules can associate quite strongly with each

other by aligning opposite charges. This association has the effect of increasing the

boiling point.

The more extended a molecule is,the stronger its induced dipole can be.More com-

pact, more spherical molecules have smaller induced dipoles and therefore lower boiling

points. A classic example is the difference between pentane and neopentane (Fig. 2.54).

FIGURE 2.54 The more extended

pentane boils at a higher temperature

than the more compact neopentane

does.

88 CHAPTER 2 Alkanes

The more spherical neopentane boils about 25 °C lower than the straight-chain isomer.

Isopentane is less extended than pentane but more extended than neopentane, and

its boiling point is right between the two, 30 °C.

Symmetry is especially important in determining melting point because highly

symmetric molecules pack well into crystal lattices. (Think of the computer game

Tetris and how easy packing would be if every shape were a highly symmetrical

square.) The better the packing of the lattice, the more energy it takes to break it up.

So neopentane, for example, melts 113 °C higher than pentane does.

CH

4

H

3

C CH

3

Methane

One signal

Ethane

One signal

Propane

Two signals, one for the CH

2

and another for the two

identical CH

3

groups

C

H H

H

3

CCH

3

FIGURE 2.55 Carbon-13 NMR

signals for three alkanes.

2.14 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the study of molecules through the investigation of their interaction

with electromagnetic radiation.There are many kinds of spectroscopy (as we shall see in

Chapter 15). One version is called nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

and is particularly valuable,both in chemistry as a device for determining molecular struc-

ture and in medicine as an imaging tool.You have heard of this form of spectroscopy before

if you have ever read an article about magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).NMR and MRI

are the same process,but the dreaded word “nuclear”must be hidden from public view.

Although we won’t go into much detail yet, this early introduction to nuclear

magnetic resonance does allow us to address the critical question of difference.When

are two atoms the same and when are they different?

Like electrons, nuclei of many atoms have a property called spin. A nonzero

nuclear spin is necessary for a nucleus to be NMR active and thus detectable by an

NMR spectrometer. The

13

C and

1

H nuclei each have spins of 1/2, just like the

electron.Although

13

C is present in only 1.1% abundance in ordinary carbon,which

is mostly

12

C, that small amount can be detected.

Like the electron, the

13

C and

1

H nuclei can be thought of as spinning in one of

two directions. In the presence of a strong magnetic field, those two spin states differ

in energy, but by only a tiny amount. Nonetheless, transitions between the two states

can be detected by NMR spectrometers tuned to the proper frequency.We’ll have more

to say about those spectrometers and those transitions in Chapter 15, but there is real-

ly not much more to it than that.So we can see a signal whenever a transition between

the lower and the higher energy nuclear spin states is induced.So what? It would seem

that we have simply built a (very expensive) machine to detect carbon or hydrogen in

a molecule,and it would be hardly surprising to find such atoms in organic molecules!

The critical point is that every different carbon (or hydrogen) in a molecule—

every such atom in a different environment, no matter how slightly different—gives a

signal that is different from that of the other carbons (or hydrogens) in the mol-

ecule.The NMR spectrometer can “count”the number of different carbons or hydro-

gens in a molecule by counting the number of signals.That ability can be enormously

useful in structure determination, and NMR spectroscopy is very often used by “the

pros”of structure determination in exactly that way.The array of signals is called the

NMR spectrum of the molecule.

Let’s use Figure 2.55 to look at a few examples. How many signals will a

13

C NMR

spectrometer “see”for methane? One, of course, because there is only one carbon. How