Jackson M.J. Micro and Nanomanufacturing

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Manufacturing High Aspect Ratio Microstructures 131

3.10 Micromold Design

Most problems in micro-molding are not caused by the filling of the

mold, but by de-molding. During de-molding, microstructures may

be torn apart, deformed, or destroyed. De-molding affects the wear

of mold inserts and deUcate parts of

the

mold insert may even be de-

stroyed after a single molding process, the microstructure is not de-

signed properly or unsuitable molding parameters are chosen. It is

possible to de-mold microstructures with vertical sidewalls, but an

inclination angle of 2° reduces de-molding forces and is even more

important than the roughness of the sidewalls. An important factor

in de-molding is the shrinkage of the polymer, which occurs when

cooling down the polymer between the filling of the mold and de-

molding. Therefore, de-molding forces also are a function of the

orientation of microstructures relative to the direction of shrinkage

and the placement of critical microstructures relative to the center of

shrinkage. This is why the path of the polymer into the mold has to

be chosen with care for injection molding. Delicate microstructures,

such as pins with high aspect ratios, can be protected against shear-

ing forces resulting from shrinkage and mold filling by neighboring

auxiliary structures that are stable enough to withstand these forces.

If a mold insert is covered with areas microstructures of different

height, or varying density, then these areas should be arranged

symmetrically on the mold insert. In this way, tilting of the mold in-

sert during molding is avoided.

3.11 Micromolding Applications

Micromolding has been employed to fabricate a variety of polymer

components. Most applications are in the field of micro-optics and

micro-fluidics, but there are also some examples of micro-(and

nano) electrical and mechanical devices. The most widely sold mi-

cromolding product probably is the well known CD and DVD for

data storage, music, and videos. Another application is the holo-

gram that is attached to a credit card [14]. Other molded micro-

optical components include spectrometers [15], optical switches

[16,17],

optical fiber components [2], waveguides [18,19], anti-

132 Micro-and Nanomanufacturing

reflective surfaces [20], optical gratings [9, 21], and photonic struc-

tures [22]. There is a variety of molded microfluidic devices, such

as pumps [23-25], valves [26-28], nebulizers [29], ink jets [29], de-

gassers for HPLC systems [30], capillary analysis systems [29, 31-

34],

devices for investigations of living cells [29,35], pressure sen-

sors [36], and flow sensors [37]. Prospective applications of thermo-

plastic molding also lie in electronics. One of them is nano imprint-

ing [38-43] which may allow for the low-cost replication of

electronic circuits with critical dimensions as small as 10 nanome-

ters.

Other future electronic applications may be electronic and op-

tical circuit boards [19], acceleration sensors [44,45], and simple de-

vices,

such as electrical switches.

3.12 Limitations of IVIicromolding

What are limitations of micromolding of thermoplastic polymers?

Nanoimprinting processes show that structures of only a few tens of

nanometers in size are replicated very well. However, there is a

limitation regarding the achievable aspect ratio of columns, grooves,

and walls. This limit is a function of the geometry of the micro-

structure, its position on the sample, the polymer type, and the proc-

ess parameters. Finite element calculations could help solve mold-

ing problems of high-aspect-ratio microstructures, but FEM codes

are available for mold filling only and the limiting process step is

de-molding of the microstructures. Development of FEM calcula-

tions of de-molding operations has recently become available [46].

3.13 Fabrication of IVIoving IVIicrostructures

When silicon-based microstructures have been produced they

have to be separated from the base that holds them. This is usually a

glass substrate that can be sacrificially etched away using wet and

vapor etchants. Owing to surface tension effects, the glass material

usually sticks to the machined silicon. Techniques have been de-

signed to prevent sticking and are known as SCREAM, SIMPLE,

and BSM processes. These techniques are self-aligned and are suit-

Manufacturing High Aspect Ratio Microstructures 133

able for batch fabrication. The release of the structure takes place in

the gaseous phase, so that there is no problem associated with stic-

tion by fluids. This section of the chapter describes the study of

plasma release techniques for bulk and surface micromachining of

silicon based materials used for the fabrication of movable micro-

mechanical structures. Here, we discuss SCREAM and SIMPLE

processes.

3.13.1 Single Crystal Reactive Etching and Metallization

(SCREAM)

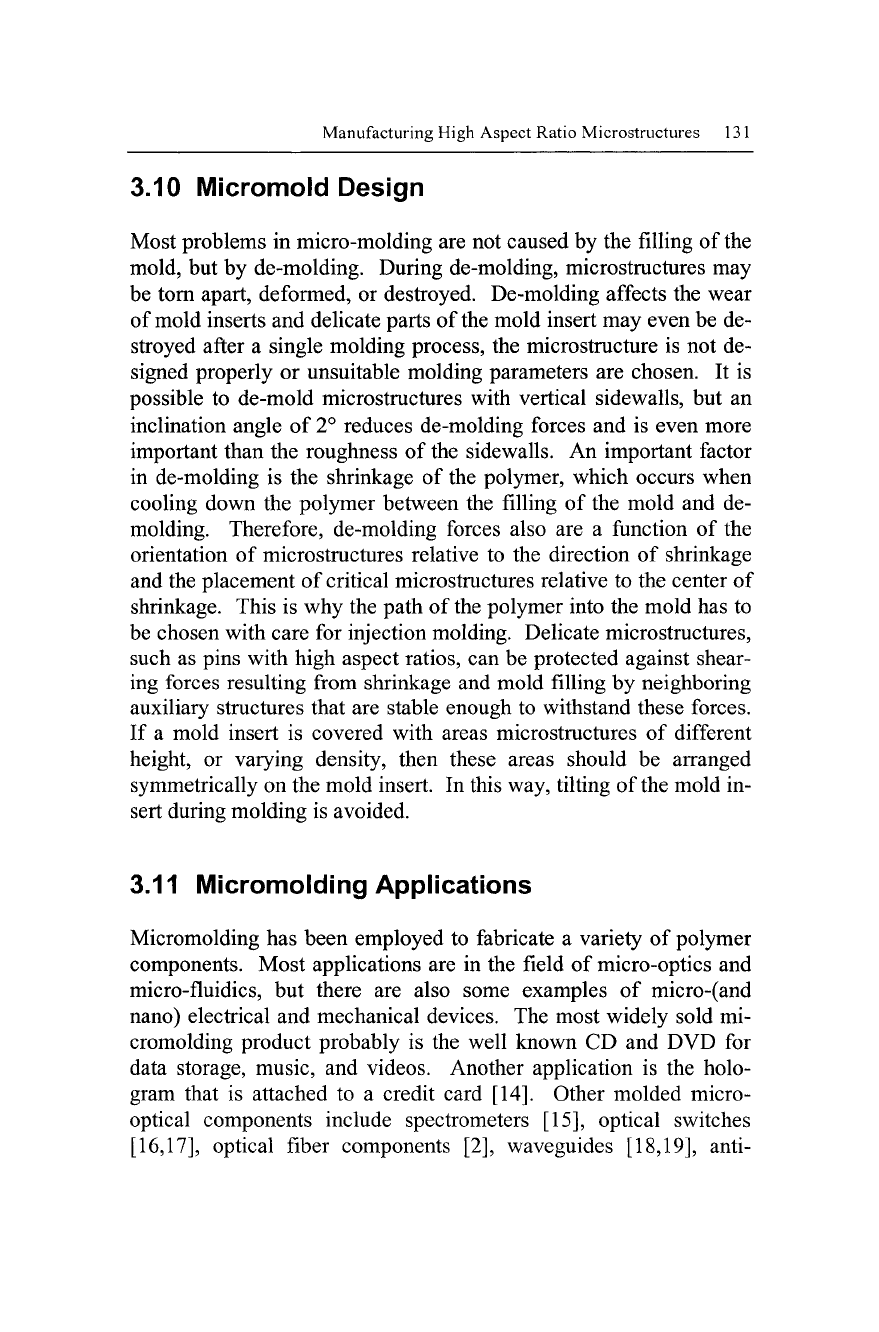

Single crystal reactive etching and metallization, or SCREAM, is

a process that consists of five basic steps (Fig. 3.19):

i^ IJJ Ul UJ ^ Ui

UMUMUi

MJ ^ IIJ IMJ

a. pip nm

amm

biSVRfffl c;BSI^SCS

c;Mi^ ^ tBim

Fig. 3.19. Dry plasma processes for manufacturing movable features: (a)

SCREAM; (b) SIMPLE; (c) BSM-SCS; (d) BSM-SOI; and (e) BSM-SISI [1]

134 Micro-and Nanomanufacturing

(1) Directional chlorine-based etching of silicon using the oxide

as a mask material;

(2) Trenches are passivated with the PECVD oxide;

(3) The oxide is then removed at the bottom of the trench using a

CHF3 plasma;

(4) An isotropic fluorine-based etch (SF6) will release the struc-

ture;

and

(5) For electrical contacting, a deposited metal layer is required.

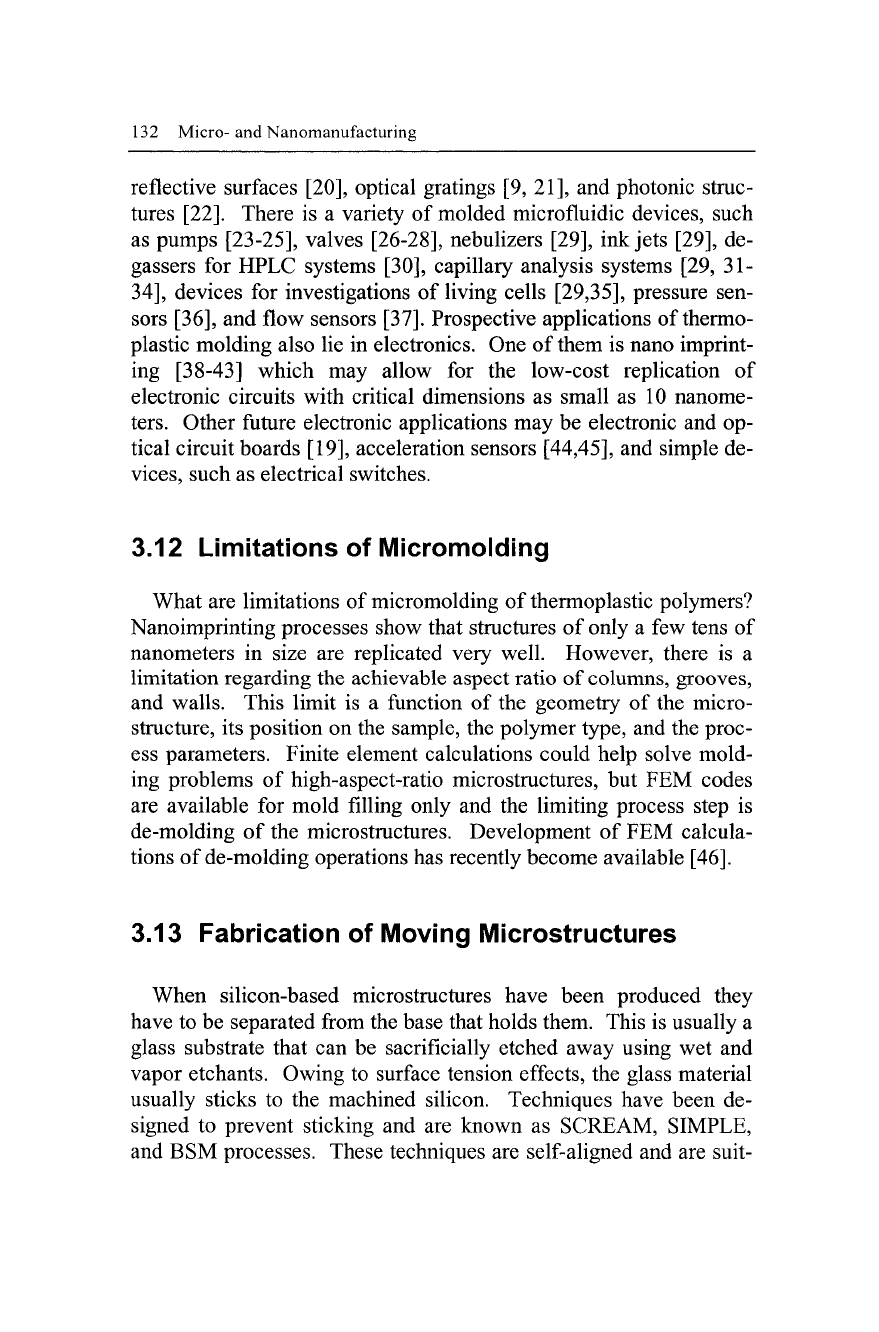

There are some disadvantages with the process, such as:

(1) The deposited PECVD layer should be tensile to avoid

buckling (Figure 3.20);

(2) The mask layer should be tensile to avoid bending after re-

lease (Figure 3.21);

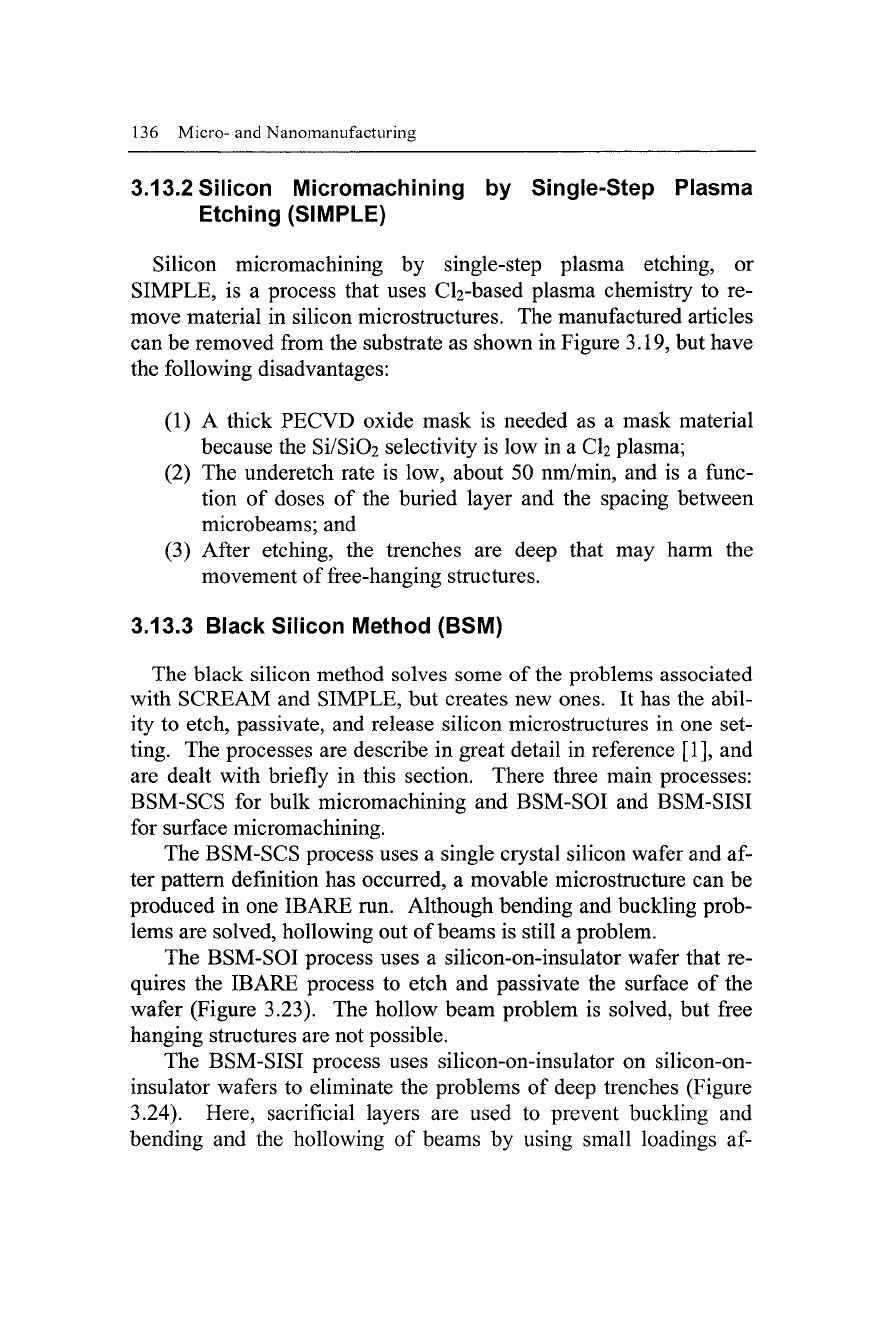

(3) The released structures are hollowed out during the isotropic

etch process (Figure 3.22); and

(4) RIE lag while etching Si directions may cause problems

during the isotropic etch because the etch depth may be

variable along the beam (Figure 3.22).

Fig. 3.20. Buckling of movable beam due to compressive stress [1]

Manufacturing High Aspect Ratio Microstructures 135

Fig. 3.21. Bending of the movable microstructure due to stress in the mask mate-

rial [1]

Fig. 3.22.

Hollowing of beams and asymetrical releasing due to RIE lag [1]

136 Micro-and Nanomanufacturing

3.13.2 Silicon IVIicromachining by Single-Step Plasma

Etching (SIMPLE)

Silicon micromachining by single-step plasma etching, or

SIMPLE, is a process that uses C^-based plasma chemistry to re-

move material in silicon microstructures. The manufactured articles

can be removed from the substrate as shown in Figure 3.19, but have

the following disadvantages:

(1) A thick PECVD oxide mask is needed as a mask material

because the Si/SiOz selectivity is low in a CI2 plasma;

(2) The underetch rate is low, about 50 nm/min, and is a func-

tion of doses of the buried layer and the spacing between

microbeams; and

(3) After etching, the trenches are deep that may harm the

movement of free-hanging structures.

3.13.3 Black Silicon Method (BSM)

The black silicon method solves some of the problems associated

with SCREAM and SIMPLE, but creates new ones. It has the abil-

ity to etch, passivate, and release silicon microstructures in one set-

ting. The processes are describe in great detail in reference [1], and

are dealt with briefly in this section. There three main processes:

BSM-SCS for bulk micromachining and BSM-SOI and BSM-SISI

for surface micromachining.

The BSM-SCS process uses a single crystal silicon wafer and af-

ter pattern definition has occurred, a movable microstructure can be

produced in one IBARE run. Although bending and buckling prob-

lems are solved, hollowing out of beams is still a problem.

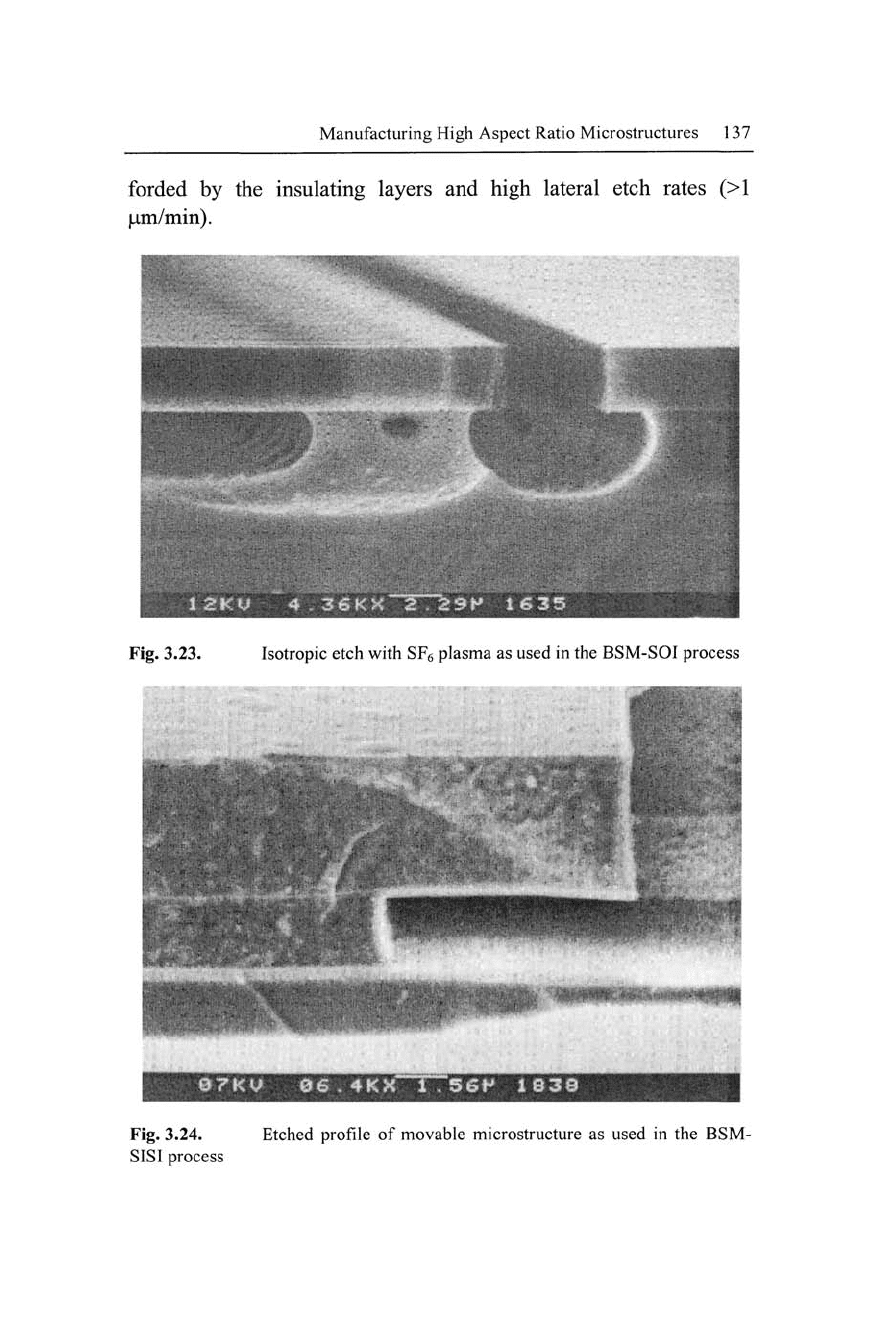

The BSM-SOI process uses a silicon-on-insulator wafer that re-

quires the IBARE process to etch and passivate the surface of the

wafer (Figure 3.23). The hollow beam problem is solved, but free

hanging structures are not possible.

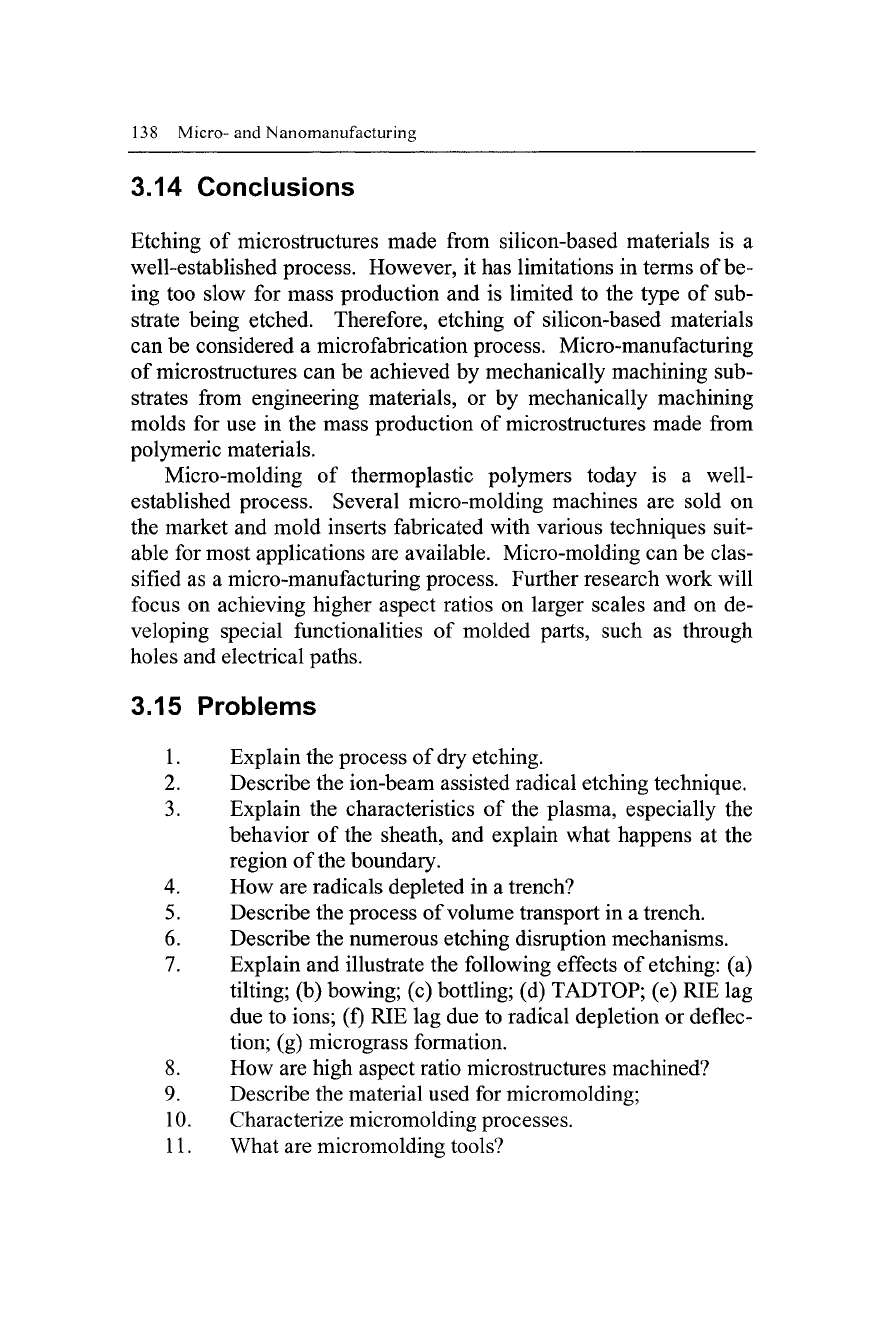

The BSM-SISI process uses silicon-on-insulator on silicon-on-

insulator wafers to eliminate the problems of deep trenches (Figure

3.24). Here, sacrificial layers are used to prevent buckling and

bending and the hollowing of beams by using small loadings af-

Manufacturing High Aspect Ratio Microstructures

137

forded

by the

insulating layers

and

high lateral etch rates

(>1

|Lim/min).

Fig. 3.23. Isotropic etch with SFg plasma

as

used

in

the BSM-SOI process

07KV 06.4KX^r756»* 1838

Fig. 3.24. Etched profile

of

movable microstructure

as

used

in the BSM-

SISI process

138 Micro-and Nanomanufacturing

3.14 Conclusions

Etching of microstructures made from silicon-based materials is a

well-established process. However, it has limitations in terms of

be-

ing too slow for mass production and is limited to the type of sub-

strate being etched. Therefore, etching of silicon-based materials

can be considered a microfabrication process. Micro-manufacturing

of microstructures can be achieved by mechanically machining sub-

strates from engineering materials, or by mechanically machining

molds for use in the mass production of microstructures made from

polymeric materials.

Micro-molding of thermoplastic polymers today is a well-

established process. Several micro-molding machines are sold on

the market and mold inserts fabricated with various techniques suit-

able for most applications are available. Micro-molding can be clas-

sified as a micro-manufacturing process. Further research work will

focus on achieving higher aspect ratios on larger scales and on de-

veloping special functionalities of molded parts, such as through

holes and electrical paths.

3.15 Problems

1.

Explain the process of dry etching.

2.

Describe the ion-beam assisted radical etching technique.

3.

Explain the characteristics of the plasma, especially the

behavior of the sheath, and explain what happens at the

region of the boundary.

4.

How are radicals depleted in a trench?

5.

Describe the process of volume transport in a trench.

6. Describe the numerous etching disruption mechanisms.

7.

Explain and illustrate the following effects of

etching:

(a)

tilting; (b) bowing; (c) bottling; (d) TADTOP; (e) RIE lag

due to ions; (f) RIE lag due to radical depletion or deflec-

tion; (g) micrograss formation.

8. How are high aspect ratio microstructures machined?

9. Describe the material used for micromolding;

10.

Characterize micromolding processes.

11.

What are micromolding tools?

Manufacturing High Aspect Ratio Microstructures 139

12.

How are micromolds designed?

References

1.

Elwenspoek J and Jansen H, Silicon Micromachining, Cambridge

University Press, 1998, Cambridge, U.K.

2.

Hanemann T, Heckele M and Plotter V, 2000, Current status of

micromolding technology, Polym. News, 25, 224-9.

3.

Wallrabe U, Dittrich H, Friedsam G, Hanemann Th, Mohr J,

Muller K, Plotter V, Ruther P, Schaller Th and ZiBler W, 2002, Micro-

molded easy-assembly multi fiber connector: RibCon, Microsyst. Tech-

nol.,

8, 83-7.

4.

Ehrfeld W, Bley P, Gotz F, Hagmann P, Maner A, Mohr J, Moser

H O, Miinchmeyer D, Schelb W, Schmidt D and Becker E W 1987 Fabri-

cation of microstructure using the LIGA process Proc. IEEE Micro-Robots

and Teleoperators Workshop (Hyannis, Cape Cod, MA, 9-11 Nov. 1987),

ed. K J Gabriel aad W S N Trimmer, IEEE Catalogue Number 87TH0204-

8.

5.

Hagmann P, Ehrfeld W and Vollmer H, 1987, Fabrication of mi-

crostructures with extreme structural heights by reaction injection molding,

First Meeting of the European Polymer Federation European Symp. On

Polymeric Materials, (Lyon, France, 14-18 Sept.), paper EPD05.

6. Heckele M, Bacher W and Mtiller K D, 1998, Hot embossing-the

molding technique for plastic microstructures, Microsyst. Technol., 4, 122-

4.

7.

Rogge T, Rummler Z and Schomburg W K, 2002, Piezo-driven

polymer microvalve manufactured by the AMANDA process, Proc. of Eu-

rosensors XVI, (Prague, 15-18 Sept. 2002), pp 214-7.

8. Niggemann M, Blaesi B, Boemer V, Gombert A, Klicker M, Kue-

bler V, Lalanne P and Wittwer V, 2001, Periodic microstructures for large

area applications generated by holography,

Conf.

Physics. Theory, and

Applications of Periodic Structures in Optics, (San Diego, CA, 1-2 Aug.

2001),

Proc. SPIE 4438,108-15.

9. Jian L, Desta Y M and Goettert J, 2001, Multilevel microstructures

and mold inserts fabricated with planar and oblique x-ray lithography of

SU-8 negative photoresist, Conf Micromachining and Microfabrication

Process Technology VII, (San Francisco, CA, 22-24 Oct. 2001), Proc.

SPIE 4557, 69-76.

10.

O'Donnell T, McCloskey P, Brunet M, Winfield R, Mathuna S C

O, Stephen A and Metev S, 2000, High aspect ratio RF coils fabricated us-

140 Micro-

and

Nanomanufacturing

ing laser processing

and

micro-molding techniques, Proc. European

Mi-

croelectronics Packaging

and

Interconnection Symposium, (Prague, Czech

Republic,

18-20

June 2000),

pp

169-74, ISBN: 80-238-5509-3.

11.

Mohr

J, 1998,

LIGA-A technology

for

fabricating microstructures

and microsystems. Sensors Mater.,

10,

363-7.

12.

Chung

S,

Hein

H,

Mohr

J,

Pantenburg

J-J and

Wallrabe

U,

2000,

LIGA technology today

and its

industrial applications, Proc. SPIEs

Int.

Conf

on

Microrobotics

and

Microassembly

II,

(Boston,

5-6 Nov.

2000),

Proc.

SPIE 4184,44-55.

13.

Martynova

L,

Locascio

L E,

Gaitan

M,

Kramer

G W,

Christensen

R

G and

MacCrehan

W

A, 1997, Fabrication of plastic microfluid channels

by imprinting methods,

Ann.

Chem., 69,4783-9.

14.

Haines

K,

1996, Development

of

embossed holograms, Proc. SPIE

2652,

45-52.

15.

Heckele

M, 1997,

Aufbau

und

Betrieb einer Kleinserienfertigung

von LIGA-Spektrometem, Swiss Plastics,

19, 5-9.

16.

Shan

X C and

Maeda

R,

2002, Development

of a

low-cost

8x8

optical switch using micro-hot embossing 2002 lEEE/LEOS

Int.

Conf

Op-

tical MEMS (Lugano, Switzerland, 20-23

Aug.

2002, IEEE (2002)),

pp

21-

2 (Catalogue

no

02EX610), ISBN: 0-7803-7595-5.

17.

Hashiura

Y,

Ikehara

T,

Kitajima

A,

Goto

H and

Maeda

R, 2001,

Optical switch array based

on

microforming process,

Conf.

Device

and

Process Technologies

for

MEMS

and

Microelectronics (Adelaide,

SA,

Austraha,

17-19

Dec. 2001), Proc. SPIE, 4592,

414-21.

18.

Ulrich

R,

Weber

H P,

Chandross

E A,

Tomlinson

W J and

Franke

E

A,

1972, Embossed optical waveguides, Appl. Phys. Lett.,

20,

213-5.

19.

Krabe

D and

Scheel

W, 1999,

Optical interconnects

by hot em-

bossing

for

module

and PCB

technology-the

EOB

approach, Proc. 49th

Electronic Components

and

Technology Conference

(San

Diego,

CA,

USA,

1-4

June

1999)

(Catalogue

no

99CH36299), ISBN: 0-7803-5231-9,

pp 1164-6.

20.

David

C,

Haberling

P,

Schnieper

M,

Sochtig

J and

Zschokke

C,

2002,

Nano-structured anti-reflective surfaces replicated

by hot

embossing,

Microelectron.

Eng.,

61-62,435-40.

21.

Knop

K 1976,

Color pictures using

the

zero diffraction order

of

phase grating structures.

Opt.

Commun., 18, 298-303.

22.

Grigaliunas

V,

Kopustinskas

V,

Meskinis

S,

Margelevicius

M,

Mikulskas

I and

Tomasiunas

R,

2001, Replication technology

for

photonic

band

gap

applications, Conf Optoelectronics

I,

Materials

and

Technolo-

gies

for

Optoelectronics Devices, Symposium

G of the

2000 E-MRS-

lUMRS-ICEM Spring

Conf.,

(Strasbourg, France,

20

May-2 June 2000),

Opt. Mater.,

17, 15-8.