Heiman G. Basic Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GETTING STARTED

To understand this chapter, recall the following:

■

From Chapter 13, the terms factor and level, how to calculate , what a

significant indicates, when to perform post hoc tests, and what indicates.

Your goals in this chapter are to learn

■

What a two-way factorial ANOVA is.

■

How to collapse across a factor to find main effect means.

■

How to calculate main effect means and cell means.

■

How to compute the in a two-way ANOVA

■

What a significant main effect indicates.

■

What a significant interaction indicates.

■

How to perform post hoc tests.

■

How to interpret the results of a two-way experiment.

Fs

2

F

F

The Two-Way Analysis

of Variance

14

318

In the previous chapter, you saw that ANOVA tests the means from one factor. In this

chapter, we’ll expand the experiment to involve two factors. Then the analysis is similar

to the previous ANOVA, except that here we compute several values of . Therefore,

be forewarned that the computations are rather involved (although they are more tedious

than difficult). Don’t try to memorize the formulas, because nowadays we usually ana-

lyze such experiments using a computer. However, you still need to understand the basic

logic, terminology, and purpose of the calculations. Therefore, the following sections

present (1) the general layout of a two-factor experiment, (2) what the ANOVA indi-

cates, (3) how to compute the ANOVA, and (4) how to interpret a completed study.

NEW STATISTICAL NOTATION

When a study involves two factors, it is called a two-way design. The two-way

ANOVA is the parametric inferential procedure that is applied to designs that involve

two independent variables. However, we have different versions of this depending on

whether we have independent or related samples. When both factors involve independ-

ent samples, we perform the two-way, between-subjects ANOVA. When both factors

involve related samples (either because of matching or repeated measures), we perform

the two-way, within-subjects ANOVA. If one factor is tested using independent sam-

ples and the other factor involves related samples, we perform the two-way, mixed-

design ANOVA. These ANOVAs are identical except for slight differences buried in

their formulas. In this chapter, we discuss the between-subjects version.

F

obt

Understanding the Two-Way Design 319

Each of our factors may contain any number of levels, so we have a code for describ-

ing a specific design. The generic format is to identify one independent variable as fac-

tor A and the other independent variable as factor B. To describe a particular ANOVA,

we use the number of levels in each factor. If, for example, factor A has two levels and

factor B has two levels, we have a two-by-two ANOVA, which is written as . Or

if one factor has four levels and the other factor has three levels, we have a or a

ANOVA, and so on.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO KNOW ABOUT THE TWO-WAY ANOVA?

It is important for you to understand the two-way ANOVA because you, and other

researchers, will often study two factors in one experiment. This is because, first, a

two-factor design tells us everything about the influence of each factor that

we would learn if it were the only independent variable. But we can also study

something that we’d otherwise miss—the interaction effect. For now, think of an

interaction effect as the influence of combining the two factors. Interactions are

important because, in nature, many variables that influence a behavior are often

simultaneously present. By manipulating more than one factor in an experiment,

we can examine the influence of such combined variables. Thus, the primary reason

for conducting a study with two (or more) factors is to observe the interaction

between them.

A second reason for multifactor studies is that once you’ve created a design

for studying one independent variable, often only a minimum of additional effort

is required to study additional factors. Multifactor studies are an efficient and cost-

effective way of determining the effects of—and interactions among—several

independent variables. Thus, you’ll often encounter two-way ANOVAs in behavioral

research. And by understanding them, you’ll be prepared to understand the even more

complex ANOVAs that will occur.

UNDERSTANDING THE TWO-WAY DESIGN

The key to understanding the two-way ANOVA is to understand how to envision it.

As an example, say that we are again interested in the effects of a “smart pill” on a

person’s IQ. We’ll manipulate the number of smart pills given to participants, calling

this factor A, and test two levels (one or two pills). Our dependent variable is a partici-

pant’s IQ score. We want to show the effect of factor A, showing how IQ scores change

as we increase dosage.

Say that we’re also interested in studying the influence of a person’s age on IQ. We’ll

call age factor B and test two levels (10- or 20-year-olds). Here, we want to show the

effect of factor B, showing how IQ scores change with increasing age.

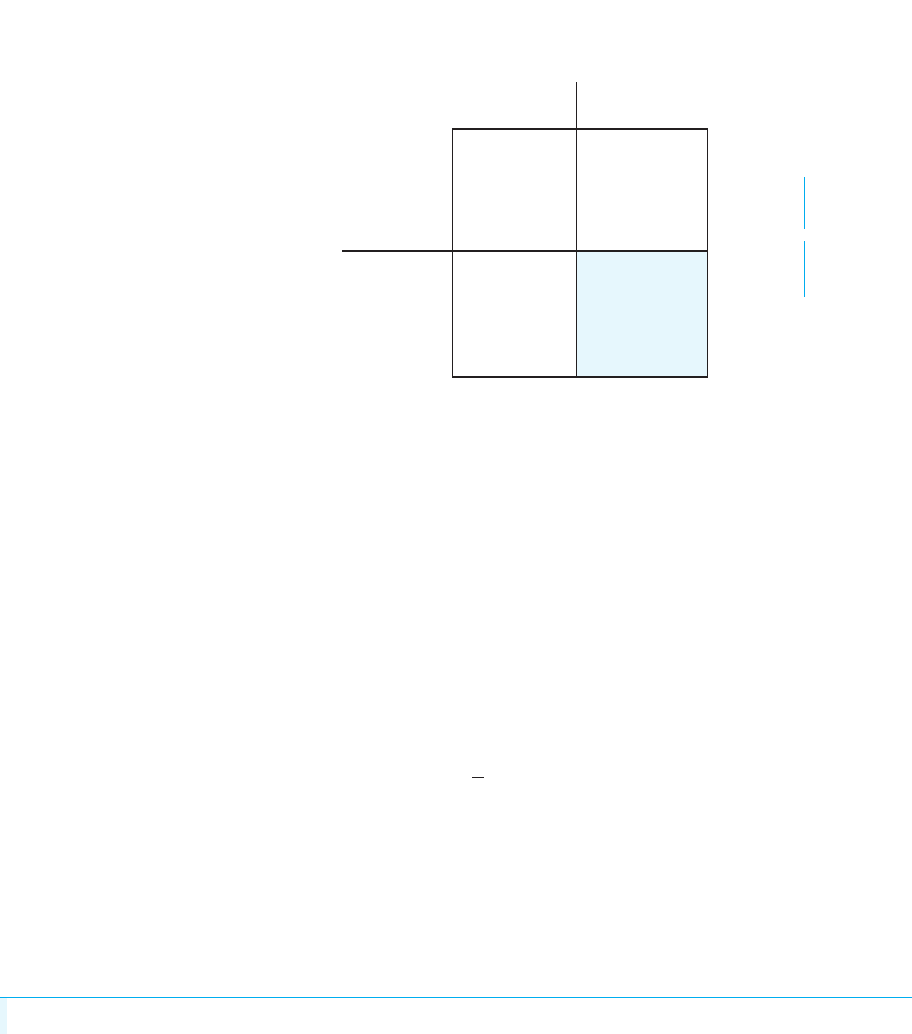

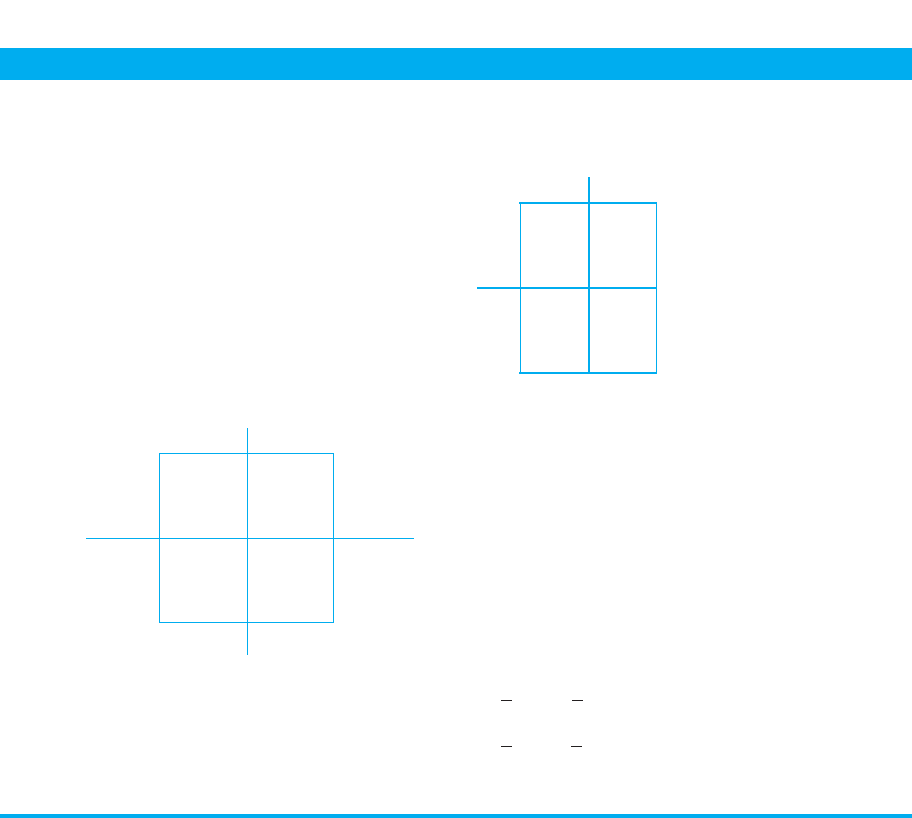

To create a two-way design, we would simultaneously manipulate both the partici-

pants’ age and the number of pills they receive. The way to envision this is to use the

matrix in Table 14.1. We always place participants’ dependent scores inside the matrix,

so here each represents a participant’s IQ score. Understand the following about this

matrix:

1. Each column represents a level of one independent variable, which here is our pill

factor. (For our formulas, we will always call the column factor “factor A.”) Thus,

for example, any score in column is from someone tested with one pill.A

1

X

3 3 4

4 3 3

2 3 2

320 CHAPTER 14 / The Two-Way Analysis of Variance

2. Each row represents one level of the other independent variable, which here is the

age factor. (The row factor is always called “factor B.”) Thus, for example, any

score in row is from a 10-year-old.

3. Each small square produced by combining a level of factor A with a level of fac-

tor B is called a cell. Here we have four cells, each containing a sample of three

participants, who are all a particular age and given the same dose of pills. For

example, the highlighted cell contains scores from 20-year-olds given two pills.

4. Because we have two levels of each factor, we have a design (it produces a

matrix).

5. We can identify each cell using the levels of the two factors. For example, the cell

formed by combining level 1 of factor A and level 1 of factor B is cell . We

can identify the mean and from each cell in the same way, so, for example, in

cell we will compute .

6. The in each cell is 3, so .

7. We have combined all of our levels of one factor with all levels of the other factor,

so we have a complete factorial design. On the other hand, in an incomplete fac-

torial design, not all levels of the two factors are combined. For example, if we had

not collected scores from 20-year-olds given one pill, we would have an incomplete

factorial design. Incomplete designs require procedures not discussed here.

OVERVIEW OF THE TWO-WAY, BETWEEN-SUBJECTS ANOVA

Now that you understand a two-way design, we can perform the ANOVA. But, enough

about smart pills. Here’s a semi-fascinating idea for a new study. Television commer-

cials are often much louder than the programs themselves because advertisers believe

that increased volume makes the commercial more persuasive. To test this, we will play

a recording of an advertising message to participants at one of three volumes. Volume

is measured in decibels, but to simplify things we’ll call the three volumes soft,

medium, and loud. Say that we’re also interested in the differences between how males

and females are persuaded, so our other factor is the gender of the listener. Therefore,

we have a two-factor experiment involving three levels of volume and two levels of

N 5 12n

X

A

1

B

1

A

1

B

1

n

A

1

B

1

2 3 2

2 3 2

B

1

Factor A: Number of Pills

Level A

1

: Level A

2

:

1 Pill 2 Pills

XX

Level B

1

: XX

←⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

10-Year-Olds XX

冧

X

苶

A

1

B

1

X

苶

A

2

B

1

Scores

Factor B:

Age

XX

Level B

2

: XX

←⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

20-Year-Olds XX

冧

X

苶

A

1

B

2

X

苶

A

2

B

2

↑

⎯⎯

One of the four cells

TABLE 14.1

Two-Way Design for

Studying the Factors of

Number of Smart Pills

and Participant’s Age

Each column contains scores

for one level of number of

pills; each row contains

scores for one level of age.

Overview of the Two-Way, Between-Subjects ANOVA 321

Factor A: Volume

Level A

1

: Level A

2

: Level A

3

:

Soft Medium Loud

9818

Level B

1

:

41217

Male

11 13 15

Factor B:

Gender

296

Level B

2

:

610 8

Female

417 4

N 18

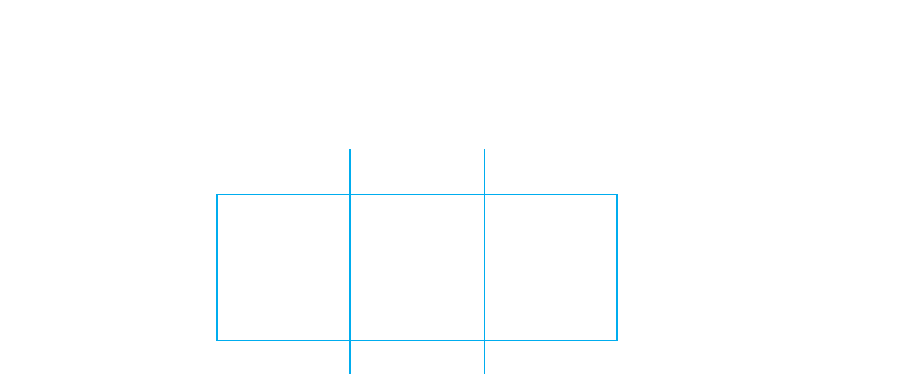

TABLE 14.2

A 3 2 Design for the

Factors of Volume and

Gender

Each column represents a

level of the volume factor;

each row represents a level of

the gender factor.

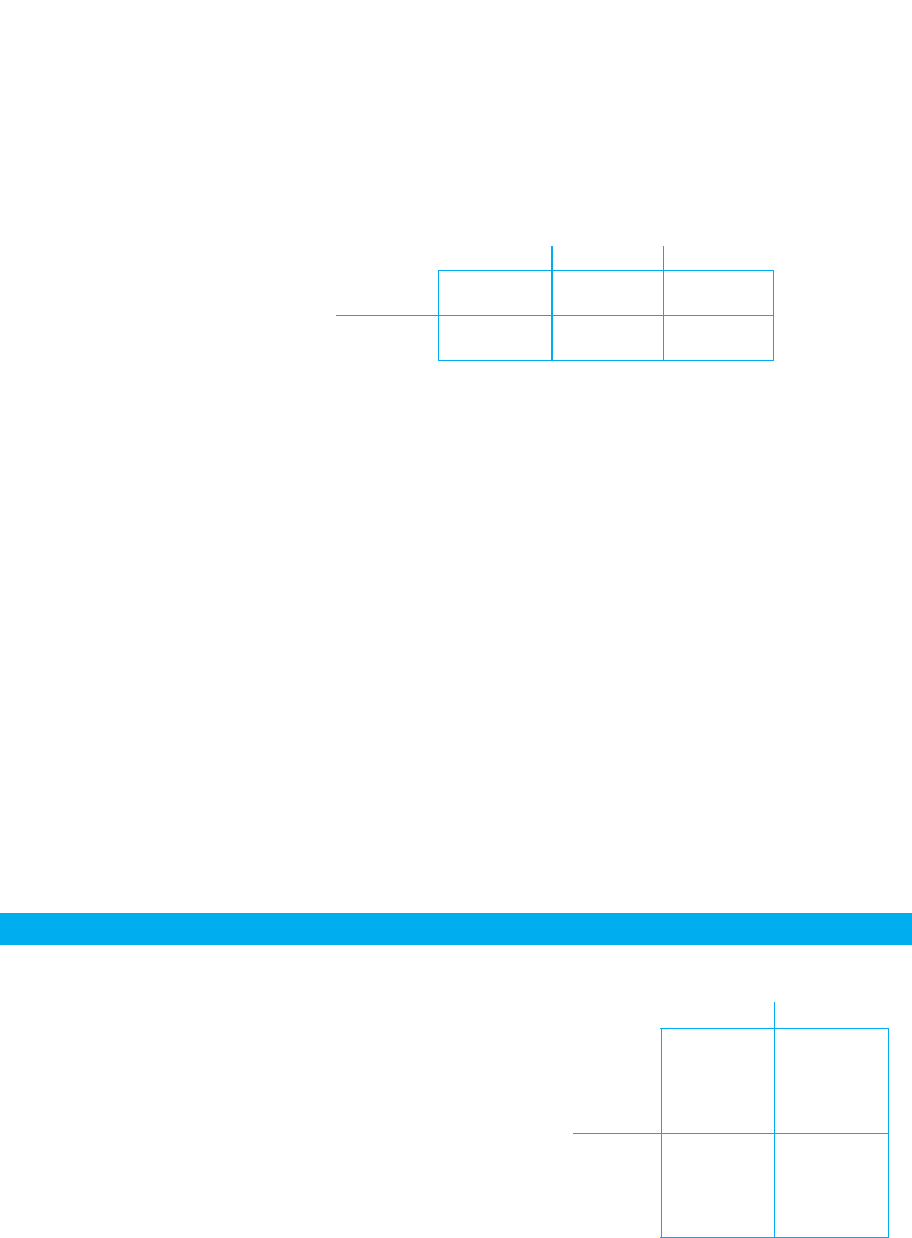

gender, so we have a design. The dependent variable indicates how persuasive

the message is, on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 25 (totally convincing).

This study is diagramed in Table 14.2 The numbers inside the cells are the persua-

siveness scores. Each column represents a level of the volume factor (factor A), and

each row represents a level of the gender factor (factor B). For simplicity we have the

unpowerful of 18: Nine men and nine women were tested, with three men and three

women hearing the message at each volume, so we have three persuasiveness scores

per cell.

But now what? As usual in any experiment, we want to conclude that if we tested the

entire population under our different conditions of volume or gender, we’d find differ-

ent populations of scores located at different . But, there is the usual problem: Our

sample data may reflect sampling error, so we might actually find the same population

and for all conditions. Therefore, once again we must eliminate the idea of sampling

error, and to do this, we perform ANOVA. As usual, first we set alpha (usually at )

and then check the assumptions.

With a complete factorial design, the assumptions of the two-way, between-subjects

ANOVA are

1. Each cell contains an independent sample.

2. The dependent variable measures normally distributed interval or ratio scores.

3. The populations have homogeneous variance.

Each cell in the persuasiveness study contains an independent sample, so we will

perform a between-subjects ANOVA. We want to determine the effect on per-

suasiveness when we change (1) the levels of the volume, (2) the levels of gender, and

(3) the interaction of volume and gender. To do so, we will examine one effect at a

time, as if we had only a one-way ANOVA involving that effect. You already under-

stand a one-way ANOVA, so the following is simply a guide for computing the various

. Any two-way ANOVA involves examining three things: the two main effects and

the interaction effect.

The Main Effect of Factor A

The main effect of a factor is the effect that changing the levels of that factor has on

dependent scores, while we ignore all other factors in the study. In the persuasiveness

study, to find the main effect of factor A (volume), we will ignore the levels of factor B

Fs

3 3 2

.05

s

N

3 3 2

322 CHAPTER 14 / The Two-Way Analysis of Variance

(gender). Literally erase the horizontal line that separates the rows of males and

females back in Table 14.2, and treat the experiment as if it were this:

Factor A: Volume

Level A

1

: Level A

2

: Level A

3

:

Soft Medium Loud

9818

41217

11 13 15

296k

A

3

610 8

417 4

X

苶

A

1

6 X

苶

A

2

11.5 X

苶

A

3

11.33

n

A

1

6 n

A

2

6 n

A

3

6

We ignore whether there are males or females in each condition, so we simply have

people. Therefore, for example, we started with three males and three females who

heard the soft message, so ignoring gender, we have six people in that level. Thus,

when we look at the main effect of A, our entire experiment consists of one factor, with

three levels of volume. The number of levels in factor A is called , so . With

six scores in each column, .

Notice that the means in the three columns are 6, 11.5, and 11.33, respectively.

So, for example, the mean for people (male and female) tested under the soft condition

is 6. By averaging together the scores in a column, we produce the main effect means

for the column factor. A main effect mean is the overall mean of one level of a factor

while ignoring the influence of the other factor. Here, we have the “main effect means

for volume.”

In statistical terminology, we produce the main effect means for volume when we

collapse across the gender factor. Collapsing across a factor means averaging together

all scores from all levels of that factor. (We averaged together the scores from males

and females.) Thus, whenever we collapse across one factor, we have the main effect

means for the remaining factor.

To see the main effect of volume, look at the overall pattern in the three main effect

means to see how persuasiveness scores change as volume increases: Scores go up

from around 6 (at soft) to around 11.5 (at medium), but then scores drop slightly to

around 11.3 (at high). To determine if these are significant differences—if there is a

significant main effect of the volume factor—we essentially perform a one-way

ANOVA that compares these three main effect means.

REMEMBER When we examine the main effect of factor A, we look at the

overall mean (the main effect mean) of each level of A, examining the col-

umn means.

The says that no difference exists between the levels of factor A in the population, so

In our study, this says that changing volume has no effect, so the three levels of volume

represent the same population of persuasiveness scores. If we reject , then we will

accept the alternative hypothesis, which is

: not all are equal

A

H

a

H

0

H

0

:

A

1

5

A

2

5

A

3

H

0

n

A

5 6

k

A

5 3k

A

Overview of the Two-Way, Between-Subjects ANOVA 323

For our study, this says that at least two levels of volume represent different popula-

tions of scores, having different .

We test by computing an called . If is significant, it indicates that at

least two main effect means from factor A differ significantly. Then we describe this

relationship by graphing the main effect means, performing post hoc comparisons to

determine which means differ significantly, and determining the proportion of variance

that is accounted for by this factor.

The Main Effect of Factor B

After analyzing the main effect of factor A, we move on to the main effect of factor B.

Therefore, we collapse across factor A (volume), so erase the vertical lines separating

the levels of volume back in Table 14.2. Then we have

9818 X

苶

B

1

11.89

Level B

1

:

41217

Male

11 13 15 n

B

1

9

k

B

2

Factor B:

Gender

296 X

苶

B

2

7.33

Level B

2

:

610 8

Female

417 4 n

B

2

9

Now we simply have the persuasiveness scores of some males and some females,

ignoring the fact that some of each heard the message at different volumes. Thus, when

we look at the main effect of B, now our entire experiment consists of one factor with

two levels. Notice that this changes things: With only two levels, is 2. And each

has changed! For example, we started with three males in soft, three in medium, and

three in loud. So, ignoring volume, we have a total of nine males (and nine females).

With nine scores per row, .

Averaging the scores in each row yields the mean persuasiveness score for each gen-

der, which are the main effect means for factor . To see the main effect of this factor,

again look at the pattern of the means: Apparently, changing from males to females

leads to a drop in scores from around 11.89 to around 7.33.

REMEMBER When we examine the main effect of factor , we look at the over-

all mean (the main effect mean) for each level of B, examining the row means.

To determine if this is a significant difference—if there is a significant main effect of

gender—we essentially perform another one-way ANOVA that compares these means.

Our says that no difference exists in the population, so

In our study, this says that our males and females represent the same population. The

alternative hypothesis is

: not all are equal

In our study, this says that our males and females represent different populations.

To test for factor B, we compute a separate , called . If is significant,

then at least two of the main effect means for factor B differ significantly. Then we

graph these means, perform post hoc comparisons, and compute the proportion of vari-

ance accounted for.

F

B

F

B

F

obt

H

0

B

H

a

H

0

:

B

1

5

B

2

H

0

B

B

n

B

5 9

nk

B

F

A

F

A

F

obt

H

0

s

Interaction Effects

After examining the main effects, we examine the effect of the interaction. The

interaction of two factors is called a two-way interaction, and results from combining

the levels of factor A with the levels of factor B. In our example, the interaction is pro-

duced by combining volume with gender. An interaction is identified as . Here,

factor A has three levels, and factor B has two levels, so it is a interaction (but

say “3 by 2”).

Because an interaction is the influence of combining the levels of both factors, we

do not collapse across, or ignore, either factor. Instead, we treat each cell in the study

as a level of the interaction and compare the cell means.

REMEMBER For the interaction effect we compare the cell means.

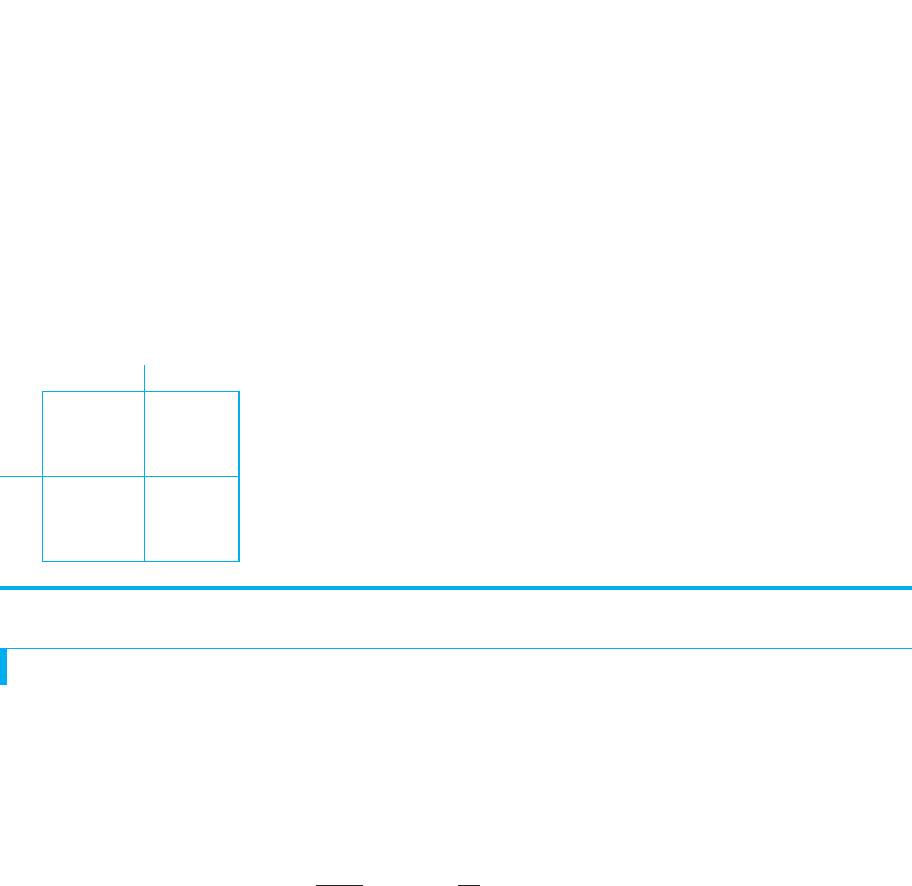

In our study, we start with the original six cells back in Table 14.2. Using the three

scores per cell, we compute the mean in each cell, obtaining the interaction means

shown in Table 14.3.

3 3 2

A 3 B

324 CHAPTER 14 / The Two-Way Analysis of Variance

■

Collapsing (averaging together) the scores from the

levels of factor B produces the main effect means

for factor A. Differences among these means reflect

the main effect of A. Collapsing the levels of A

produces the main effect means for factor B.

Differences among these means reflect the main

effect of B.

MORE EXAMPLES

Let’s say that our previous “smart pill” and age study

produced the following IQ scores:

Factor A: Dose

One Pill Two Pills

100 140

10 years 105 145 X

苶

125

110 150

Factor B:

Age

110 110

20 years 115 115 X

苶

115

120 120

X

苶

110 X

苶

130

The column means are the main effect means for dose:

The main effect is that mean IQ increases from 110 to

130 as dosage increases. The row means are the main

effect means for age: The main effect is that mean IQ

decreases from 125 to 115 as age increases.

For Practice

In this study,

A

1

A

2

25

B

1

24

23

11 7

B

2

10 6

95

1. Each equals ____, and each equals ____.

2. The means produced by collapsing across factor B

equal ____ and ____. They are called the ____

means for factor ____.

3. What is the main effect of A?

4. The means produced by collapsing across factor A

are ____ and ____. They are called the ____ means

for factor ____.

5. What is the main effect of B?

Answers

1. 6; 6

2. ; ; main effect; A

3. Changing from to produces a decrease in scores.

4. ; ; main effect; B

5. Changing from to produces an increase in scores.B

2

B

1

X

B

2

5 8X

B

1

5 3

A

2

A

1

X

A

2

5 5X

A

1

5 6

n

B

n

A

A QUICK REVIEW

Factor A: Volume

Soft Medium Loud

Male X

苶

8 X

苶

11 X

苶

16.67

Factor B:

Gender

Female X

苶

4 X

苶

12 X

苶

6

k 6

n 3

TABLE 14.3

Cell Means for the

Volume by Gender

Interaction

Overview of the Two-Way, Between-Subjects ANOVA 325

Notice that things have changed again. For , now we have six cells, so .

For , we are looking at the scores in only one cell at a time, so our “cell size” is 3,

so .

Thus, now our experiment is somewhat like one “factor” with six levels, with three

scores per level. We will determine if the mean in the male–soft cell is different from in

the male–medium cell or from in the female–soft cell, and so on. However, examining an

interaction is not as simple as saying that the cell means are significantly different. Inter-

preting an interaction is difficult because both independent variables are changing, as well

as the dependent scores. To simplify the process, look at the influence of changing the

levels of factor A under one level of factor B. Then see if this effect—this pattern—for

factor A is different when you look at the other level of factor B. For example, here is the

first row from Table 14.3, showing the relationship between volume and scores for the

males. What happens? As volume increases, mean persuasiveness scores also increase, in

an apparently positive, linear relationship.

Factor A: Volume

B

1

:

Soft Medium Loud

male X

苶

8 X

苶

11 X

苶

16.67

But now look at the relationship between volume and persuasiveness scores for the

females.

Factor A: Volume

Soft Medium Loud

B

2

:

female

X

苶

4 X

苶

12 X

苶

6

Here, as volume increases, mean persuasiveness scores first increase but then decrease,

producing a nonlinear relationship.

Thus, there is a different relationship between volume and persuasiveness scores for

each gender level. A two-way interaction effect is present when the relationship

between one factor and the dependent scores changes with, or depends on, the level of

the other factor that is present. Thus, whether increasing volume always increases

scores depends on whether we’re talking about males or females. In other words, an

interaction effect occurs when the influence of changing one factor is not the same for

each level of the other factor. Here we have an interaction effect because increasing the

volume does not have the same effect for males as it does for females.

n

A3B

5 3

n

k

A3B

5 6k

326 CHAPTER 14 / The Two-Way Analysis of Variance

You can also see the interaction by looking at the difference between males and

females at each volume back in Table 14.3. Who scores higher, males or females? It

depends on which level of volume we’re talking about.

Conversely, an interaction effect would not be present if the cell means formed the

same pattern for males and females. For example, say that the cell means had been as

follows:

Factor A: Volume

Soft Medium Loud

Male X

苶

5 X

苶

10 X

苶

15

Factor B:

Gender

Female X

苶

20 X

苶

25 X

苶

30

Here, each increase in volume increases scores by about 5 points, regardless of whether

it’s for males or females. (Or, females always score higher, regardless of volume.)

Thus, an interaction effect is not present when the influence of changing the levels of

one factor does not depend on which level of the other variable is present. Or, in other

words, there’s no interaction when there is the same relationship between the scores

and one factor for each level of the other factor.

REMEMBER A two-way interaction effect indicates that the influence that one

factor has on scores depends on which level of the other factor is present.

To determine if there is a significant interaction effect in our data, we essentially per-

form another one-way ANOVA that compares the cell means. To write the and

in symbols is complicated, but in words, is that the cell means do not represent an

interaction effect in the population, and is that at least some of the cell means do

represent an interaction effect in the population.

To test , we compute another , called . If is significant, it indicates

that at least two of the cell means differ significantly in a way that produces an interac-

tion effect. Then, as always, we graph the interaction, perform post hoc comparisons to

determine which cell means differ significantly, and compute the proportion of vari-

ance accounted for by the interaction.

F

A3B

F

A3B

F

obt

H

0

H

a

H

0

H

a

H

0

■

We examine the interaction effect by looking at the

cell means. An effect is present if the relationship

between one factor and the dependent scores

changes as the levels of the other factor change.

MORE EXAMPLES

Here are the data again when factor A is dose of the

smart pill and factor B is age of participants.

Factor A: Dose

One Pill Two Pills

100 140

10 years 105 145

110 150

X

苶

105 X

苶

145

Factor B:

Age

110 110

20 years 115 115

120 120

X

苶

115 X

苶

115

A QUICK REVIEW

(continued)

Computing the Two-Way ANOVA 327

COMPUTING THE TWO-WAY ANOVA

We’ve seen that a two-way ANOVA involves three : one for the main effect of factor

A, one for the main effect of factor B, and one for the interaction effect of . The

logic for each of these is the same as in the one-way ANOVA discussed in Chapter 13:

should equal 1 if is true. The larger the , however, the less likely that is

true. If is larger than , we will reject .

Previously when we computed we saw two important formulas to keep in mind:

The describes the variability within groups and is our estimate of . It is com-

puted as the “average” variability in the cells. The is our one estimate of the error

variance used in all three ratios. We compute by computing and dividing

by

The indicates the differences between our sample means, as an estimate of

However, because we have two main effects and the interaction, we have three

sources of between-groups variance, so we compute three mean squares. Thus, for the

main effect of factor A, we compute the sum of squares between groups for A ,

divide by the degrees of freedom for A , and have the mean square between

groups for A . For the main effect of B, we compute the sum of squares between

groups for B , divide by the degrees of freedom for B , and have the mean

square between groups for B ( ). For the interaction, we compute the sum of squares

between groups , divide by the degrees of freedom , and have the mean

square between groups .1MS

A3B

2

1df

A3B

21SS

A3B

2

MS

B

1df

B

21SS

B

2

1MS

A

2

1df

A

2

1SS

A

2

σ

2

treat

.

MS

bn

df

wn

.

SS

wn

MS

wn

F

MS

wn

σ

2

error

MS

wn

MS 5

SS

df

F

obt

5

MS

bn

MS

wn

F

obt

H

0

F

crit

H

0

H

0

F

obt

H

0

F

obt

A 3 B

Fs

Look at the cell means in one row at a time: We see an

interaction effect because the influence of increasing

dose depends on participants’ age. Dosage increases

mean IQ for 10-year-olds from 105 to 145, but it does

not change mean IQ for 20-year-olds (always at 115).

Or, looking at each column, the influence of increasing

age depends on dose. With 1 pill, 20-year-olds score

higher (115) than 10-year-olds (105), but with 2 pills

10-year-olds score higher (145) than 20-year-olds (115).

For Practice

A study produces these data:

A

1

A

2

25

B

1

24

23

11 7

B

2

10 6

95

1. The means to examine for the interaction are

called the ____ means.

2. When we change from to for , the cell

means are ____ and ____.

3. When we change from to for , the cell

means are ____ and ____.

4. How does the influence of changing from to

depend on the level of that is present?

5. Is an interaction effect present?

Answers

1. cell

2. 2, 4

3. 10, 6

4. Under the means increase, under they decrease.

5. Yes

B

2

B

1

B

A

2

A

1

B

2

A

2

A

1

B

1

A

2

A

1