Heiman G. Basic Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

288 CHAPTER 12 / The Two-Sample t-Test

samples who had or had not completed the course). The dependent variable was

the ability to resolve a domestic dispute. These success scores were obtained:

No Course Course

11 13

14 16

10 14

12 17

811

15 14

12 15

13 18

912

11 11

(a) Should a one-tailed or a two-tailed test be used? (b) What are and ?

(c) Subtracting course from no course, compute and determine whether it is

significant. (d) Compute the confidence interval for the difference between the

(e) What conclusions can the experimenter draw from these results? (f) Using our

two approaches, compute the effect size and interpret it.

22. When reading a research article, you encounter the following statements. For

each, identify the , the design, the statistical procedure performed and the result,

the relationship, and if a Type I or Type II error is possibly being made.

(a) “The t-test indicated a significant difference between the mean for men

and for women , with , . Unfortunately,

the effect size was only .” (b) “The t-test indicated that participants’ weights

after three weeks of dieting were significantly reduced relative to the pretest

measure, with , , and .”

INTEGRATION QUESTIONS

23. How do you distinguish the independent variable from the dependent variable?

(Ch. 2)

24. What is the difference between an experiment versus a correlational study in

terms of (a) the design? (b) How we examine the relationship? (c) How sampling

error might play a role? (Chs. 2, 4, 7, 11, 12)

25. (a) When do you perform parametric inferential procedures in experiments?

(b) What are the four parametric inferential procedures for experiments that we

have discussed and what is the design in which each is used? (Chs. 10, 11, 12)

26. In recent chapters, you have learned about three different versions of a confidence

interval. (a) What are they called? (b) How are all three similar in terms of what

they communicate? (c) What are the differences between them? (Chs. 11, 12)

27. (a) What does it mean to “account for variance”? (b) How do we predict scores in

an experiment? (c) Which variable in an experiment is potentially the good

predictor and important? (d) When does that occur? (Chs. 5, 7, 8, 12)

28. (a) In an experiment, what are the three ways to try to maximize power?

(b) What does maximizing power do in terms of our errors? (c) For what

outcome is it most important for us to have maximum power and why?

(Chs. 10, 11, 12)

r

2

pb

5 .16p 6 .05t14025 3.56

.08

p 6 .01t15825 7.931M 5 9.321M 5 5.42

N

s.

t

obt

H

a

H

0

29. You have performed a one-tailed t-test. When computing a confidence interval,

should you use the one-tailed or two-tailed ? (Chs. 11, 12)

30. For the following, identify the inferential procedure to perform and the key infor-

mation for answering the research question. Note: If no inferential procedure is

appropriate, indicate why. (a) Ten students are tested for accuracy of distance esti-

mation when using one or both eyes. (b) We determine that the average number of

cell phone calls in a sample of college students is 7.2 per hour. We want to

describe the likely national average () for this population. (c) We compare chil-

dren who have siblings to those who do not, rank ordering the children in terms of

their willingness to share their toys. (d) Two gourmet chefs have rank ordered the

10 best restaurants in town. How consistently do they agree? (e) We measure the

influence of sleep deprivation on driving performance for groups having 4 or 8

hours sleep. (f) We test whether wearing black uniforms produces more

aggression by comparing the mean number of penalties a hockey team receives

per game when wearing black to the league average for teams with non-black

uniforms. (Chs. 11, 12)

t

crit

■ ■ ■ SUMMARY OF

FORMULAS

1. To perform the independent samples t-test:

2. The formula for the confidence interval for the

difference between two ms is

3. To perform the related samples t-test:

s

D

5

B

s

2

D

N

s

2

D

5

©D

2

2

1©D2

2

N

N 2 1

1s

X

1

2X

2

211t

crit

21 1X

1

2 X

2

2

1s

X

1

2X

2

212t

crit

21 1X

1

2 X

2

2#

1

2

2

#

df 5 1n

1

2 121 1n

2

2 12

t

obt

5

1X

1

2 X

2

22 1

1

2

2

2

s

X

1

2X

2

s

X

1

2X

2

5

B

s

2

pool

a

1

n

1

1

1

n

2

b

s

2

pool

5

1n

1

2 12s

2

1

1 1n

2

2 12s

2

2

1n

1

2 121 1n

2

2 12

s

2

X

5

©X

2

2

1©X2

2

N

N 2 1

4. The formula for the confidence interval for m is

5. The formula for Cohen’s d for independent

samples is

6. The formula for Cohen’s for related samples is

7. The formula for is

With independent samples,

With related samples, .df 5 N 2 11n

2

2 12

df 5 1n

1

2 121

r

2

pb

5

1t

obt

2

2

1t

obt

2

2

1 df

r

2

pb

d 5

D

2s

2

D

d

d 5

X

1

2 X

2

2s

2

pool

1s

D

212t

crit

21 D #

D

# 1s

D

211t

crit

21 D

D

df 5 N 2 1

t

obt

5

D 2

D

s

D

Integration Questions 289

GETTING STARTED

To understand this chapter, recall the following:

■

From Chapter 5, variance indicates variability, which is the differences between

scores. Also, it is called “error variance.”

■

From Chapter 10, why we limit the probability of a Type I error to .

■

From Chapter 12, what independent and related samples are, how we “pool” the

sample variances to estimate the variance in the population, and what effect size

is and why it is important.

Your goals in this chapter are to learn

■

The terminology of analysis of variance.

■

When and how to compute

■

Why should equal 1 if is true, and why it is greater than 1 if is false.

■

When to compute Fisher’s protected t-test or Tukey’s HSD.

■

How eta squared describes effect size.

H

0

H

0

F

obt

F

obt

.

.05

The One-Way Analysis

of Variance

13

290

Believe it or not, we have only one more common inferential procedure to learn and

it is called the analysis of variance. This is the parametric procedure used in experi-

ments involving more than two conditions. This chapter will show you (1) the

general logic behind the analysis of variance, (2) how to perform this procedure for

one common design, and (3) how to perform an additional analysis called post hoc

comparisons.

NEW STATISTICAL NOTATION

The analysis of variance has its own language that is also commonly used in research

publications:

1. Analysis of variance is abbreviated as ANOVA.

2. An independent variable is also called a factor.

3. Each condition of the independent variable is also called a level, or a treatment,

and differences in scores (and behavior) produced by the independent variable are

a treatment effect.

4. The symbol for the number of levels in a factor is k.

An Overview of ANOVA 291

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO KNOW ABOUT ANOVA?

It is important to know about analysis of variance because it is the most common infer-

ential statistical procedure used in experiments. Why? Because there are actually many

versions of ANOVA, so it can be used with many different designs: It can be applied to

an experiment involving independent samples or related samples, to an independent

variable involving any number of conditions, and to a study involving any number of

independent variables. Such complex designs are common because, first, the hypothe-

ses of the study may require comparing more than two conditions of an independent

variable. Second, researchers often add more conditions because, after all of the time

and effort involved in creating two conditions, little more is needed to test additional

conditions. Then we learn even more about a behavior (which is the purpose of

research). Therefore, you’ll often encounter the ANOVA when conducting your own

research or when reading about the research of others.

AN OVERVIEW OF ANOVA

Because different versions of ANOVA are used depending on the design of a study, we

have important terms for distinguishing among them. First, a one-way ANOVA is per-

formed when only one independent variable is tested in the experiment (a two-way

ANOVA is used with two independent variables, and so on). Further, different versions

of the ANOVA depend on whether participants were tested using independent or

related samples. However, in earlier times participants were called “subjects,” and in

ANOVA, they still are. Therefore, when an experiment tests a factor using independent

samples in all conditions, it is called a between-subjects factor and requires the

formulas from a between-subjects ANOVA. When a factor is studied using related

samples in all levels, it is called a within-subjects factor and involves a different set

of formulas called a within-subjects ANOVA. In this chapter, we’ll discuss the one-

way, between-subjects ANOVA. (The slightly different formulas for a one-way, within-

subjects ANOVA are presented in Appendix A.3.)

As an example of this type of design, say we conduct an experiment to determine

how well people perform a task, depending on how difficult they believe the task will

be (the “perceived difficulty” of the task). We’ll create three conditions containing the

unpowerful of five participants each and provide them with the same easy ten math

problems. However, we will tell participants in condition 1 that the problems are easy,

in condition 2 that the problems are of medium difficulty, and in condition 3 that the

problems are difficult. Thus, we have three levels of the factor of perceived difficulty.

Our dependent variable is the number of problems that participants then correctly solve

within an allotted time. If participants are tested under only one condition and we do

not match them, then this is a one-way, between-subjects design.

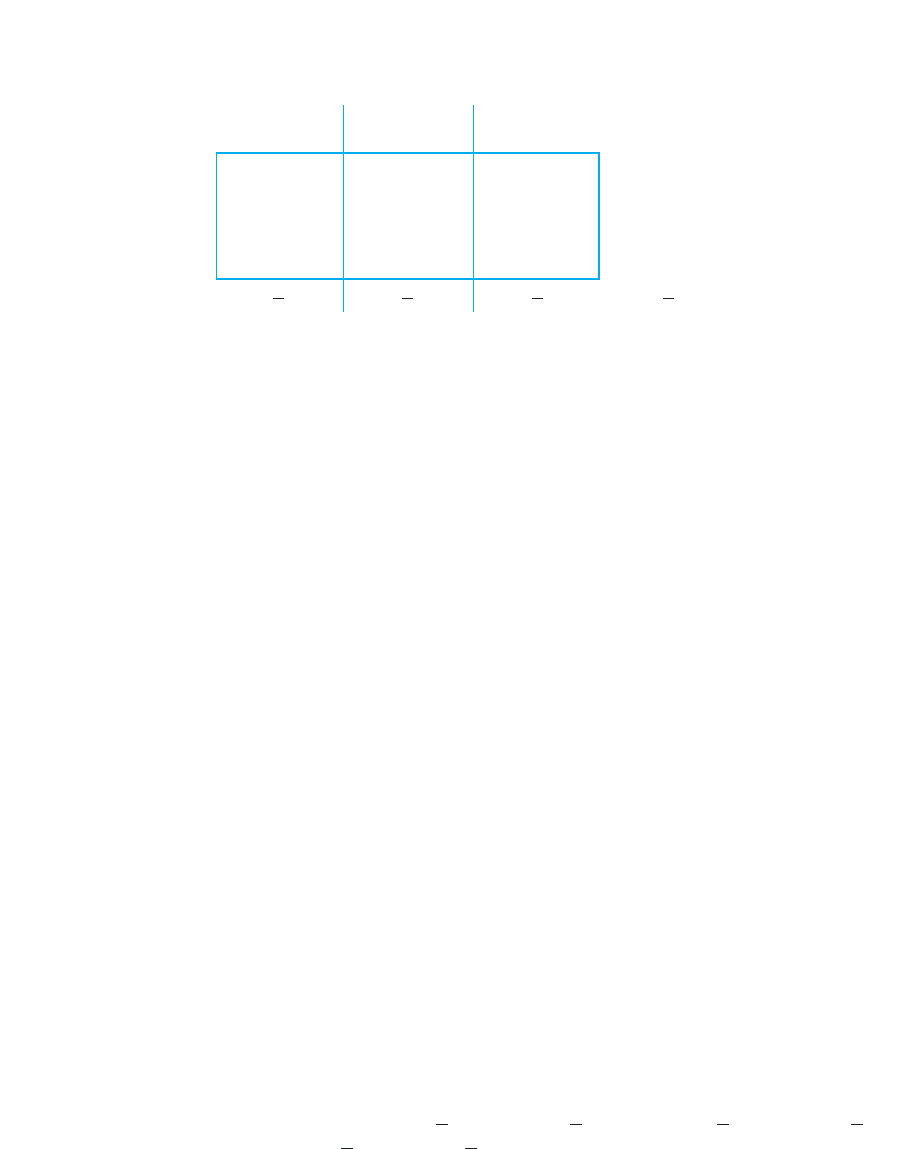

The way to diagram a one-way ANOVA is shown in Table 13.1. Each column is a

level of the factor, containing the scores of participants tested under that condition (here

symbolized by ). The symbol stands for the number of scores in a condition, so here

per level. The mean of each level is the mean of the scores from that column.

With three levels in this factor, . (Notice that the general format is to label the fac-

tor as factor , with levels , , , and so on.) The total number of scores in the

experiment is , and here . Further, the overall mean of all scores in the experi-

ment is the mean of all 15 scores.

N 5 15N

A

3

A

2

A

1

A

k 5 3

n 5 5

nX

n

292 CHAPTER 13 / The One-Way Analysis of Variance

Factor A: Independent Variable of

Perceived Difficulty

Level A

1

: Level A

2

: Level A

3

: Conditions

Easy Medium Difficult k ⴝ 3

XXX

XXX

XXX

XXX

XXX

Overall

N 5 15n

3

5 5n

2

5 5n

1

5 5

X

X

3

X

2

X

1

➝

TABLE 13.1

Diagram of a Study

Having Three Levels

of One Factor

Each column represents

a condition of the

independent variable.

Although we now have three conditions, our purpose is still to demonstrate a relation-

ship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. Ideally, we’ll find a

different mean for each condition, suggesting that if we tested the entire population under

each level of difficulty, we would find three different populations of scores, located at three

different . However, it’s possible that we have the usual problem: Maybe the inde-

pendent variable really does nothing to scores, the differences between our means reflect

sampling error, and actually we would find the same population of scores, having the same

, for all levels of difficulty. Therefore, as usual, before we can conclude that a relation-

ship exists, we must eliminate the idea that our sample means poorly represent that no rela-

tionship exists. The analysis of variance is the parametric procedure for determining

whether significant differences occur in an experiment containing two or more conditions.

Thus, when you have only two conditions, you can use either a two-sample t-test or the

ANOVA: You’ll reach exactly the same conclusions, and both have the same probability

of making Type I and Type II errors. However, you must use ANOVA when you have more

than two conditions (or more than one independent variable).

Otherwise, the ANOVA has the same assumptions as previous parametric proce-

dures. Performing a one-way, between-subjects ANOVA is appropriate when

1. The experiment has only one independent variable and all conditions contain

independent samples.

2. The dependent variable measures normally distributed interval or ratio scores.

3. The variances of the populations are homogeneous.

Although the in all conditions need not be equal, violations of the assumptions are

less serious when the are equal. Also, the procedures are much easier to perform

with equal .

How ANOVA Controls the Experiment-Wise Error Rate

You might be wondering why we even need ANOVA. Couldn’t we use the independent-

samples t-test to test for significant differences among the three means above? That

is, we might test whether differs from , then whether differs from , and

finally whether differs from . We cannot use this approach because of the resulting

probability of making a Type I error (rejecting a true ).

To understand this, we must first distinguish between making a Type I error when

comparing a pair of means as in the t-test, and making a Type I error somewhere in the

experiment when there are more than two means. In our example, we have three means

H

0

X

3

X

1

X

3

X

2

X

2

X

1

ns

ns

ns

s

An Overview of ANOVA 293

so we can make a Type I error when comparing to , to , or to . Techni-

cally, when we set , it is the probability of making a Type I error when we

make one comparison. However, it also defines what we consider to be an acceptable

probability of making a Type I error anywhere in an experiment. The probability of

making a Type I error anywhere among the comparisons in an experiment is called the

experiment-wise error rate.

We can use the t-test when comparing the only two means in an experiment because

with only one comparison, the experiment-wise error rate equals . But with more than

two means in the experiment, performing multiple t-tests results in an experiment-wise

error rate that is much larger than . Because of the importance of avoiding Type I

errors, however, we do not want the error rate to be larger than we think it is, and it

should never be larger than . Therefore, we perform ANOVA because then our

actual experiment-wise error rate will equal the alpha we’ve chosen.

REMEMBER The reason for performing ANOVA is that it keeps the experiment-

wise error rate equal to .

Statistical Hypotheses in ANOVA

ANOVA tests only two-tailed hypotheses. The null hypothesis is that there are no

differences between the populations represented by the conditions. Thus, for our

perceived difficulty study, with the three levels of easy, medium, and difficult, we have

In general, for any ANOVA with levels, the null hypothesis is

The “ ” indicates that there are as many as there are levels.

You might think that the alternative hypothesis would be However, a

study may demonstrate differences between some but not all conditions. For example,

perceived difficulty may only show differences in the population between our easy and

difficult conditions. To communicate this idea, the alternative hypothesis is

: not all are equal

implies that a relationship is present because two or more of our levels represent dif-

ferent populations.

As usual, we test , so ANOVA always tests whether all of our level means repre-

sent the same .

The Order of Operations in ANOVA: The F Statistic

and Post Hoc Comparisons

The statistic that forms the basis for ANOVA is . We compute , which we com-

pare to , to determine whether any of the means represent different .

When is not significant, it indicates no significant differences between any

means. Then the experiment has failed to demonstrate a relationship, we are finished

with the statistical analyses, and it’s back to the drawing board.

When is significant, it indicates only that somewhere among the means two or

more of them differ significantly. However, does not indicate which specific means

differ significantly. Thus, if for the perceived difficulty study is significant, we will

know that we have significant differences somewhere among the means of the easy,

medium, and difficult levels, but we won’t know where they are.

F

obt

F

obt

F

obt

F

obt

sF

crit

F

obt

F

H

0

H

a

sH

a

1

?

2

?

3

.

s

. . .

5

k

. . .

5

k

.

H

0

:

1

5

2

5k

H

0

:

1

5

2

5

3

.05

5 .05

X

3

X

1

X

3

X

2

X

2

X

1

294 CHAPTER 13 / The One-Way Analysis of Variance

■

The one-way ANOVA is performed when testing

two or more conditions from one independent

variable.

■

A significant followed by post hoc comparisons

indicates which level means differ significantly, with

the experiment-wise error rate equal to .

MORE EXAMPLES

We measure the mood of participants after they have

won $0, $10, or $20 in a rigged card game. With one

independent variable, a one-way design is involved,

and the factor is the amount of money won. The levels

are $0, $10, or $20. If independent samples receive

each treatment, we perform the between-subjects

ANOVA. (Otherwise, perform the within-subjects

ANOVA.) A significant will indicate that at least

two of the conditions produced significant differences

in mean mood scores. Perform post hoc comparisons

to determine which levels differ significantly, compar-

ing the mean mood scores for $0 vs. $10, $0 vs. $20,

and $10 vs. $20. The probability of a Type I error in

the study—the experiment-wise error rate—equals .

F

obt

F

obt

For Practice

1. A study involving one independent variable is a

____ design.

2. Perform the ____ when a study involves independ-

ent samples; perform the ____ when it involves

related samples.

3. An independent variable is also called a ____, and

a condition is also called a ____, or ____.

4. The ____ will indicate whether any of the

conditions differ, and then the ____ will indicate

which specific conditions differ.

5. The probability of a Type I error in the study is

called the ____.

Answers

1. one-way

2. between-subjects ANOVA; within-subjects ANOVA

3. factor; level; treatment

4. ; post hoc comparisons

5. experiment-wise error rate

F

obt

A QUICK REVIEW

UNDERSTANDING THE ANOVA

The logic and components of all versions of the ANOVA are very similar. In each case,

the analysis of variance does exactly that—it “analyzes variance.” This is the same con-

cept of variance that we’ve talked about since Chapter 5. But we do not call it variance.

Therefore, when is significant we perform a second statistical procedure, called

post hoc comparisons. Post hoc comparisons are like t-tests in which we compare all

possible pairs of means from a factor, one pair at a time, to determine which means dif-

fer significantly. Thus, for the difficulty study, we’ll compare the means from easy and

medium, from easy and difficult, and from medium and difficult. Then we will know

which of our level means actually differ significantly from each other. By performing

post hoc comparisons after is significant, we ensure that the experiment-wise prob-

ability of a Type I error equals our .

REMEMBER If is significant, then perform post hoc comparisons to

determine which specific means differ significantly.

The one exception to this rule is when you have only two levels in the factor. Then

the significant difference indicated by must be between the only two means in the

study, so it is unnecessary to perform post hoc comparisons.

F

obt

F

obt

F

obt

F

obt

Understanding the ANOVA 295

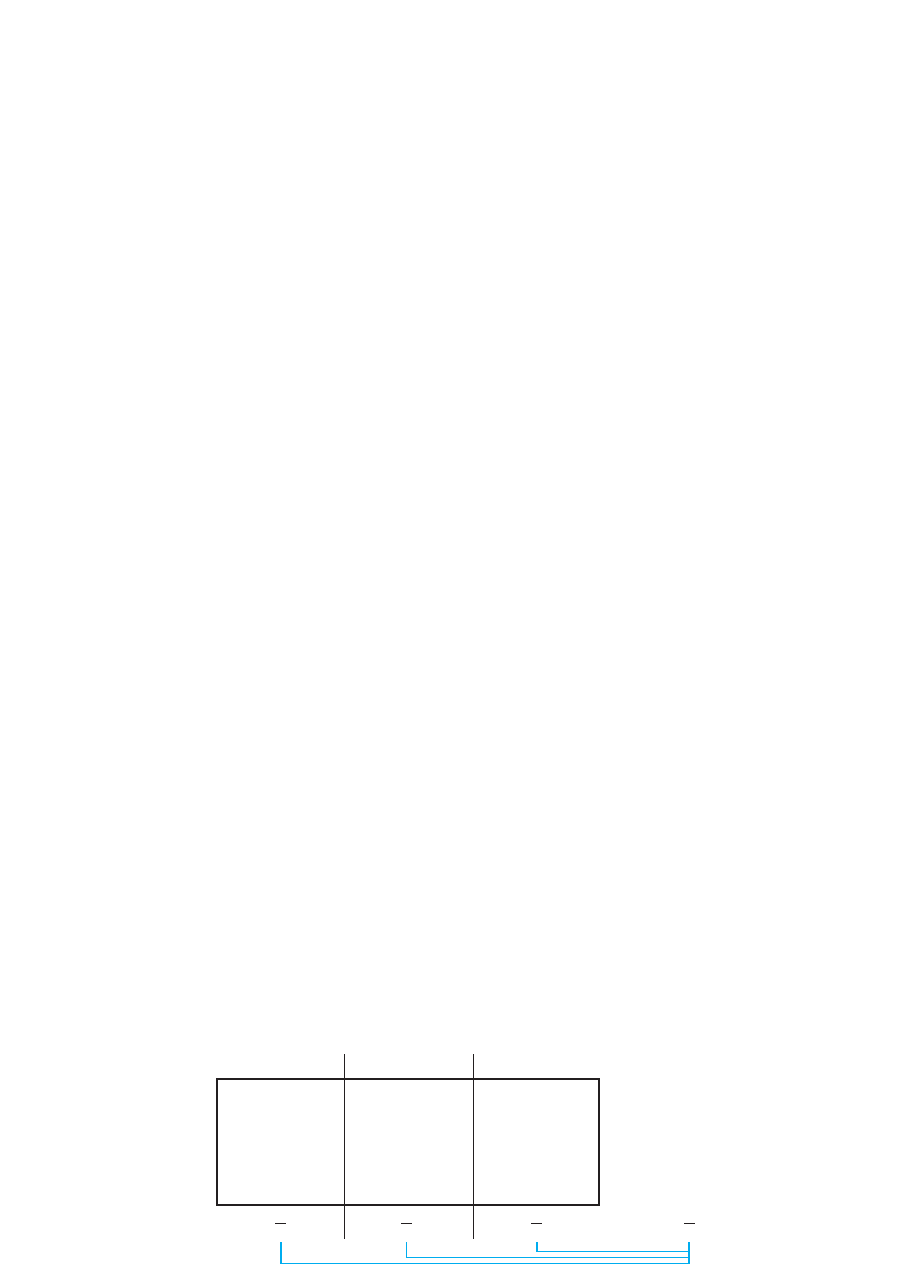

Factor A

Level A

1

: Level A

2

: Level A

3

:

XXX

XXX

XXX

XXX

XXX

X

3

X

2

X

1

TABLE 13.2

How to Conceptualize

the Computation of MS

wn

Here, we find the

difference between each

score in a condition and

the mean of that

condition.

Instead, ANOVA has its own terminology. We begin with the formula for the estimated

population variance:

In the numerator we find the sum of the squared deviations between the mean and each

score. In ANOVA, the “sum of the squared deviations” is shortened to sum of squares,

which is abbreviated as . In the denominator we divide by , which is our

degrees of freedom or . Recall that dividing the sum of the squared deviations by

produces something like the average or the mean of the squared deviations. In ANOVA,

this is shortened to mean square, which is symbolized as .

Thus, when we compute we are computing an estimate of the population vari-

ance. In the ANOVA we compute variance from two perspectives, called the mean

square within groups and the mean square between groups.

The Mean Square within Groups

The mean square within groups describes the variability of scores within the condi-

tions of an experiment. Its symbol is . You can conceptualize the computation of

as shown in Table 13.2: First, we find the variance in level 1 (finding how much

the scores in level 1 differ from ), then we find the variance of scores in level 2

around , and then we find the variance of scores in level 3 around . Although each

sample provides an estimate of the population variability, we obtain a better estimate

by averaging or “pooling” them together, like we did in the independent-samples t-test.

Thus, the is the “average” variability of the scores in each condition.

We compute by looking at the scores within one condition at a time, so the dif-

ferences among those scores are not influenced by our independent variable. Therefore,

the value of stays the same, regardless of whether is true or false. Either way,

is an estimate of the variance of scores in the population If is true and we

are representing one population, then estimates the of that population. If is

correct and we are representing more than one population, because of homogeneity of

variance, estimates the one value of that would occur in each population.

REMEMBER The is an estimate of the variability of individual scores

in the population.

The Mean Square between Groups

The other variance computed in ANOVA is the mean square between groups.

The mean square between groups describes the variability between the means of our

MS

wn

σ

2

x

MS

wn

H

a

σ

2

X

MS

wn

H

0

1σ

2

X

2.MS

wn

H

0

MS

wn

MS

wn

MS

wn

X

3

X

2

X

1

MS

wn

MS

wn

MS

MS

dfdf

N 2 1SS

S

2

X

5

©1X 2 X2

2

N 2 1

5

sum of squares

degrees of freedom

5

SS

df

5 mean square 5 MS

296 CHAPTER 13 / The One-Way Analysis of Variance

levels. It is symbolized by . You can conceptualize the computation of as

shown in Table 13.3.

We compute variability as the differences between a set of scores and their mean, so

here, we treat the level means as scores, finding the “average” amount they deviate

from their mean, which is the overall mean of the experiment. In the same way that the

deviations of raw scores around the mean describe how different the scores are from

each other, the deviations of the sample means around the overall mean describe how

different the sample means are from each other.

Thus, is our way of measuring how much the means of our levels differ from

each other. This serves as an estimate of the differences between sample means that

would be found in one population. That is, we are testing the that our data all come

from the same, one population. If so, sample means from that population will not nec-

essarily equal or each other every time, because of sampling error. Therefore, when

is true, the differences between our means as measured by will not be zero.

Instead, is an estimate of the “average” amount that sample means from that one

population differ from each other due to chance, sampling error.

REMEMBER The describes the differences between our means as an

estimate of the differences between means found in the population.

As we’ll see, performing the ANOVA involves first using our data to compute the

and . The final step is to then compare them by computing .

Comparing the Mean Squares: The Logic of the F-Ratio

The test of is based on the fact that statisticians have shown that when samples of

scores are selected from one population, the size of the differences among the sample

means will equal the size of the differences among individual scores. This makes sense

because how much the sample means differ depends on how much the individual scores

differ. Say that the variability in the population is small so that all scores are very close

to each other. When we select samples of such scores, we will have little variety in

scores to choose from, so each sample will contain close to the same scores as the next

and their means also will be close to each other. However, if the variability is very

large, we have many different scores available. When we select samples of these scores,

we will often encounter a very different batch each time, so the means also will be very

different each time.

REMEMBER In one population, the variability of sample means will equal

the variability of individual scores.

H

0

F

obt

MS

bn

MS

wn

MS

bn

MS

bn

MS

bn

H

0

H

0

MS

bn

MS

bn

MS

bn

Factor A

Level A

1

: Level A

2

: Level A

3

:

XX X

XX X

XX X

XX X

XX X

Overall X

X

3

X

2

X

1

TABLE 13.3

How to Conceptualize

the Computation of MS

bn

Here, we find the

difference between the

mean of each condition

and the overall mean of

the study.

Understanding the ANOVA 297

Here is the key: the estimates the variability of sample means in the population

and the estimates the variability of individual scores in the population. We’ve just

seen that when we are dealing with only one population, sample means and individual

scores will differ to the same degree. Therefore, when we are dealing with only one

population, the should equal : the answer we compute for should be

the same answer as for . Our always says that we are dealing with only one

population, so if is true for our study, then our should equal our .

An easy way to determine if two numbers are equal is to make a fraction out of them,

which is what we do when computing .F

obt

MS

wn

MS

bn

H

0

H

0

MS

wn

MS

bn

MS

wn

MS

bn

MS

wn

MS

bn

This fraction is referred to as the -ratio. The -ratio equals the divided by the

. (The is always on top!)

If we place the same number in the numerator as in the denominator, the ratio will

equal 1. Thus, when is true and we are representing one population, the should

equal the , so should equal 1. Or, conversely, when equals 1, it tells us

that is true.

Of course may not equal 1 exactly when is true, because we may have

sampling error in either or That is, either the differences among our

individual scores and/or among our level means may be “off” in representing the cor-

responding differences in the population. Therefore, realistically, we expect that, if

is true, will equal 1 or at least will be close to 1. In fact, if is less than 1,

mathematically it can only be that is true and we have sampling error in represent-

ing this. (Each is a variance, in which we square differences, so cannot be

negative.)

It gets interesting, however, as becomes larger than 1. No matter what our data

show, implies that is “trying” to equal 1, and if it does not, it’s because of sam-

pling error. Let’s think about that. If , it is twice what says it should be,

although according to , we should conclude “No big deal—a little sampling error.”

Or, say that , so the is four times the size of (and is four times

what it should be). Yet, says that would have equaled but by chance we

happened to get a few unrepresentative scores. If is, say, 10, then it, and the ,

are ten times what says they should be! Still, says this is because we had a little

bad luck in representing the population.

As this illustrates, the larger the , the more difficult it is to believe that our data

are poorly representing the situation where is true. Of course, if sampling error

won’t explain so large an , then we need something else that will. The answer is

our independent variable. When is true so that changing our conditions produces

different populations of scores, will not equal , and will not equal 1.

Further, the more that changing the levels of our factor changes scores, the larger will

be the differences between our level means, and so the larger will be . However,

recall that the value of stays the same regardless of whether is true.

Thus, greater differences produced by our factor will produce only a larger ,MS

bn

H

0

MS

wn

MS

bn

F

obt

MS

wn

MS

bn

H

a

F

obt

H

0

F

obt

H

0

H

0

MS

bn

F

obt

MS

wn

MS

bn

H

0

F

obt

MS

wn

MS

bn

F

obt

5 4

H

0

H

0

F

obt

5 2

F

obt

H

0

F

obt

F

obt

MS

H

0

F

obt

F

obt

H

0

MS

wn

.MS

bn

H

0

F

obt

H

0

F

obt

F

obt

MS

wn

MS

bn

H

0

MS

bn

MS

wn

MS

bn

FF

The formula for is

F

obt

5

MS

bn

MS

wn

F

obt