Heiman G. Basic Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

278 CHAPTER 12 / The Two-Sample t-Test

f

μ

D

DD DDDDD

0

DD DDDDD

+t

obt

= +2.88

(D = +3.6)

+t

crit

= +2.132

Values of t

Larger positive Ds

...

–2.0 –1.0

0 +1.0 +2.0 ...

Larger negative Ds

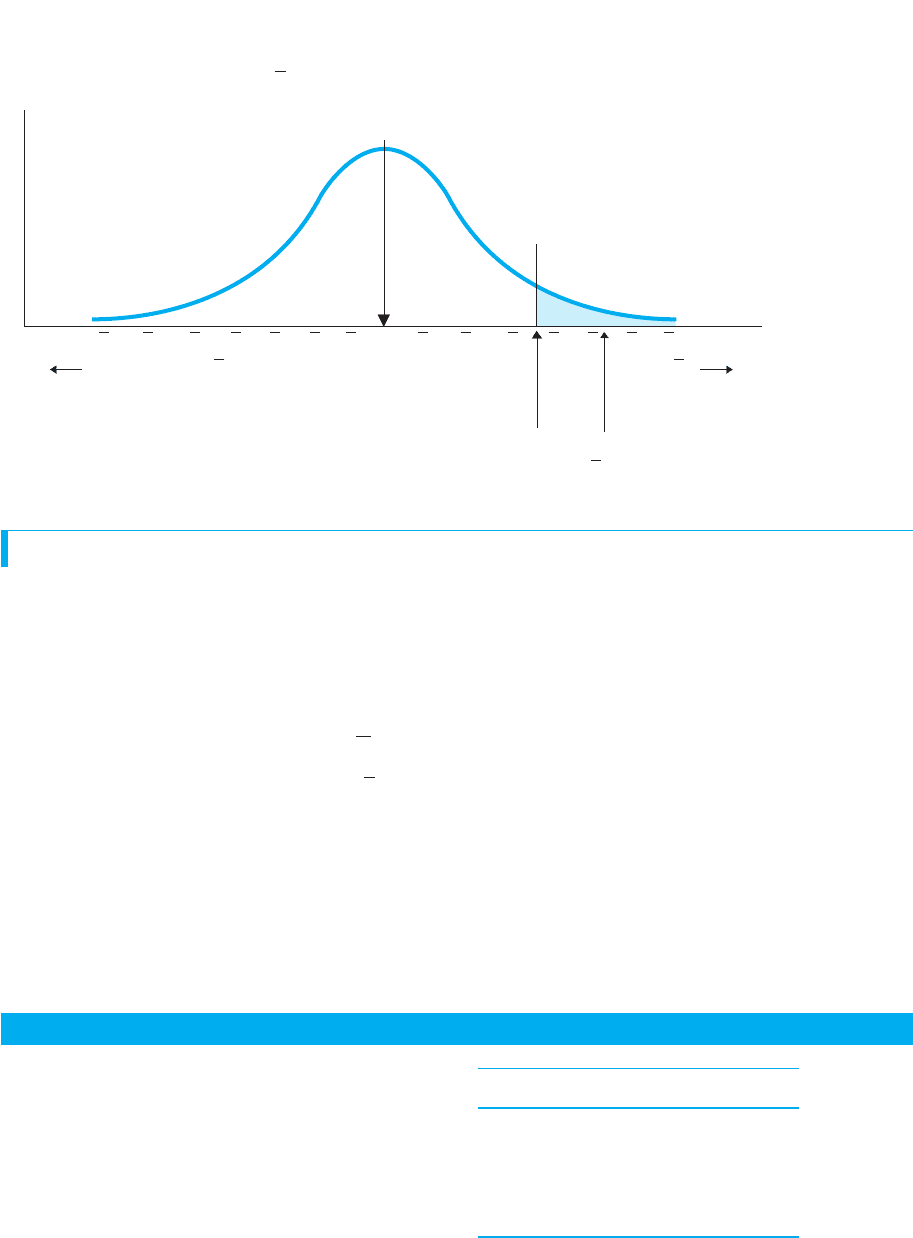

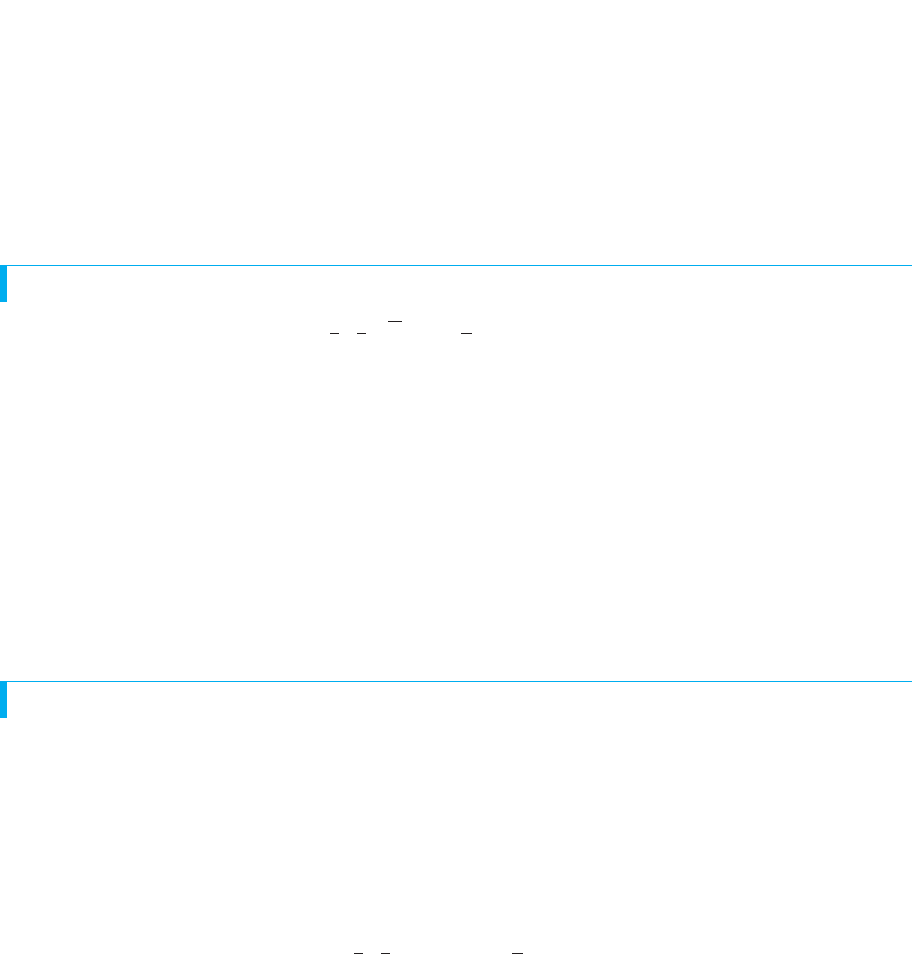

FIGURE 12.6

One-Tailed Sampling Distribution of When 0

D

5Ds

■

Perform the related-samples t-test with a matched-

groups or repeated-measures design.

MORE EXAMPLES

In a two-tailed study, we compare husband-and-wife

pairs, with and . Subtracting

wife – husband produces

H

a

:

D

? 0H

0

:

D

5 0

Wife HusbandD

4 6 2

583

396

583

㛬㛬㛬 㛬㛬㛬 㛬㛬㛬

X

苶

4.25 X

苶

7.75 D

苶

3.5

A QUICK REVIEW

SUMMARY OF THE RELATED-SAMPLES t-TEST

After checking that the design is matched samples or repeated measures and meets the

assumptions, the related-samples t-test involves the following:

1. Create either the two-tailed or one-tailed and .

2. Compute :

a. Compute the difference score for each pair of scores.

b. Compute and .

c. Compute .

d. Compute .

3. Find : In the t-tables, use .

4. Compare to : If is beyond , the results are significant; describe the

populations of raw scores and interpret the relationship. If is not beyond ,

the results are not significant; make no conclusion about the relationship.

5. Compute the confidence interval for m .

D

t

crit

t

obt

t

crit

t

obt

t

crit

t

obt

df 5 N 2 1t

crit

t

obt

s

D

s

2

D

D

t

obt

H

a

H

0

(continued)

DESCRIBING THE RELATIONSHIP IN A TWO-SAMPLE EXPERIMENT

In either two-sample t-test, the fact that is significant is not the end of the story. If

you stop after hypothesis testing, then you’ve found a relationship, but you have not

described it. Instead, whenever (and only) when you have significant results, you

should fully describe the relationship in your sample data. This involves two steps—

graphing the results and computing “effect size.”

Graphing the Results of a Two-Sample Experiment

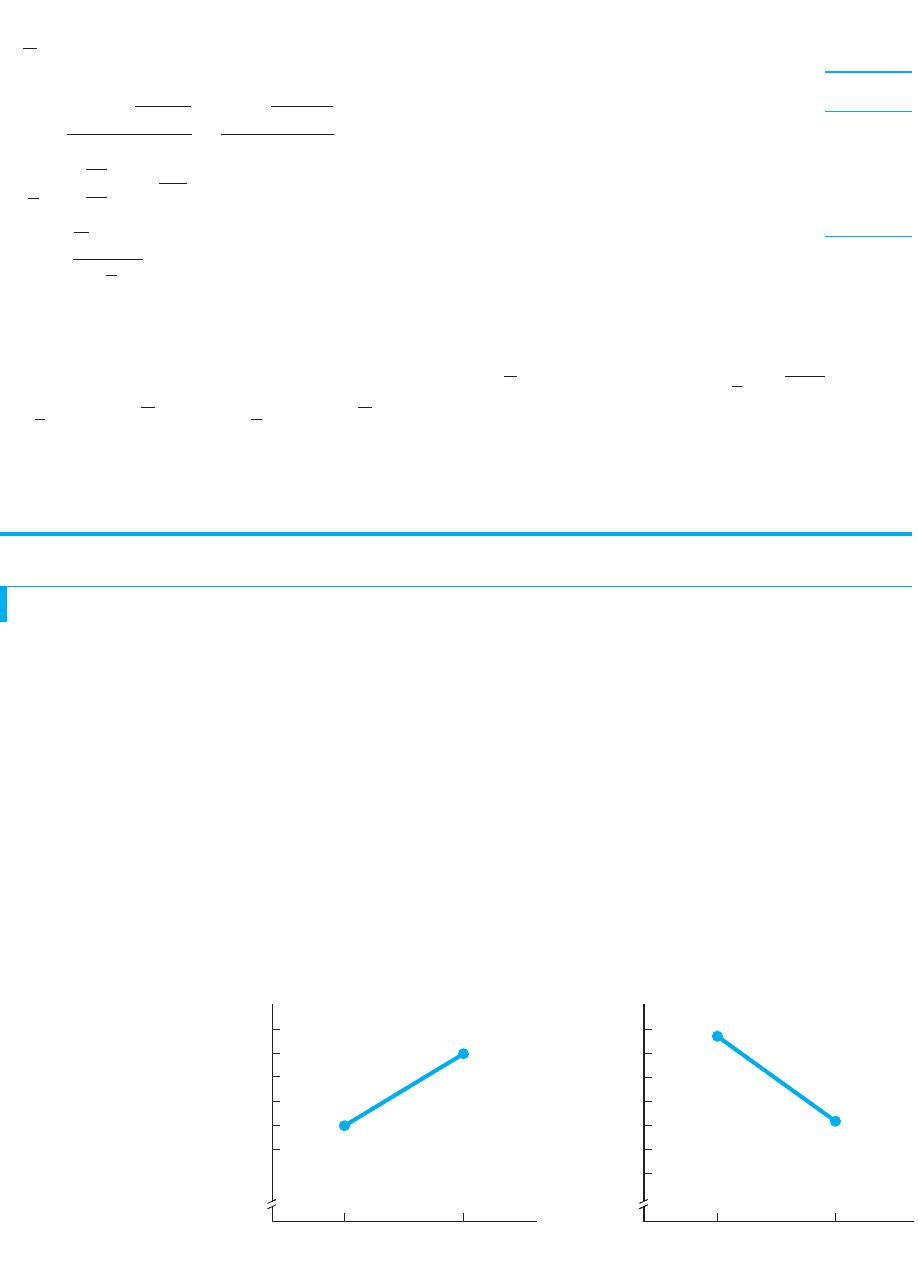

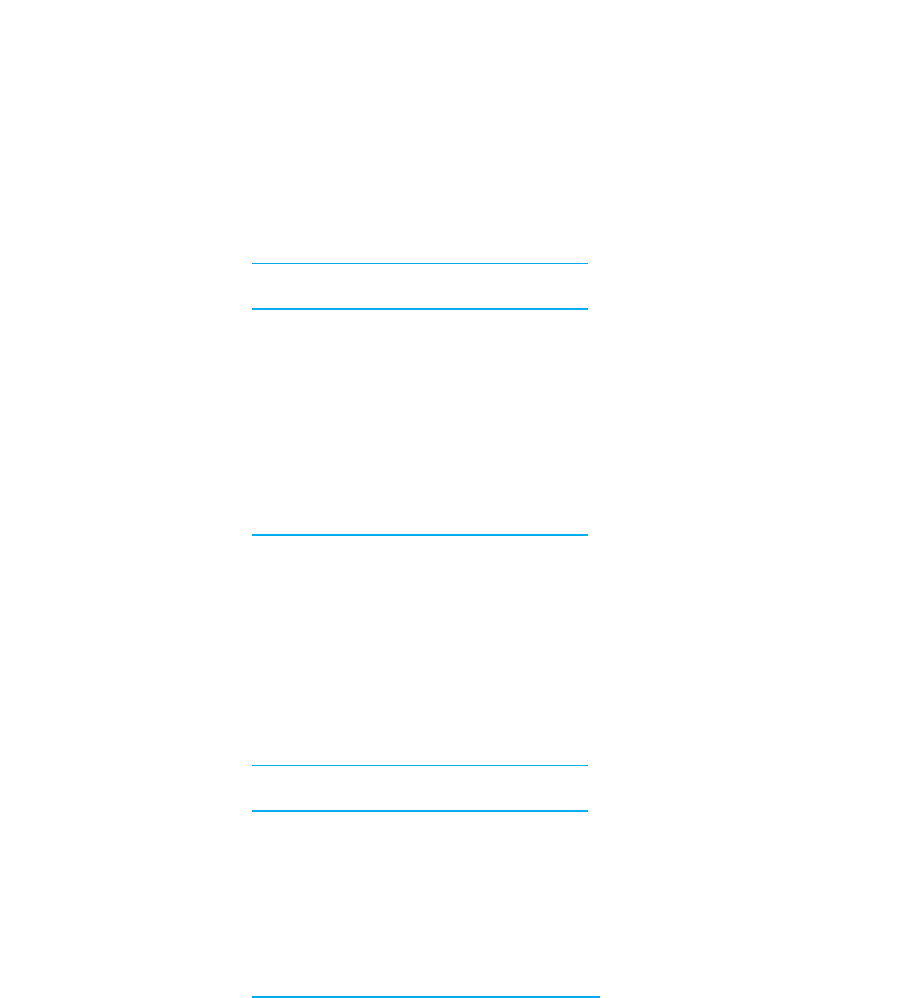

From Chapter 4, you know that we plot the mean of each condition on the axis and

the conditions of the independent variable on the axis. The results of our previous

studies are shown in Figure 12.7. Notice that for the phobia study the means of the orig-

inal fear scores from the before and after conditions are plotted, not the .Ds

X

Y

t

obt

With and , is The is

significant. For wives, we expect is 4.25, and for

husbands, we expect is 7.75. For the confidence

interval of ,

26.256 #

D

#20.744

1.8662113.1822123.5 5

1.8662123.1822123.5 #

D

#

1s

D

212t

crit

21 D #

D

# 1s

D

212t

crit

21 D

D

t

obt

;3.182t

crit

df 5 3␣ 5 .05

t

obt

5

D 2

D

s

D

5 123.5 2 02>.866 524.04

s

D

5

B

s

2

D

N

5 23>4 5 .866

s

2

D

5

©D

2

2

1©D2

2

N

N 2 1

5

58 2

12142

2

4

3

5 3.0

D 5214>4 523.5

For Practice

A two-tailed study with repeated

measures gives

AB

87

10 5

96

85

11 6

1. What are and ?

2. Subtracting A – B, perform the

t-test.

3. Compute the confidence interval of .

4. Subtracting A – B, what are and if we pre-

dicted that B would produce lower scores?

Answers

1. ;

2. ; : ;

With ,

and is significant.

3.

4. ; H

a

:

D

7 0H

0

:

D

# 0

1.324 #

D

# 5.476

1.7482122.77621 3.4 #

D

# 1.7482112.77621 3.4 5

t

obt

t

crit

5 ;2.776

␣ 5 0.5t

obt

5 13.4 2 02>.748 514.55.

s

D

5 12.8>5 5 .748s

2

D

5 2.8D 5 17>5 513.4

H

a

:

D

? 0H

0

:

D

5 0

H

a

H

0

D

H

a

H

0

Degree of hypnosis

24

23

22

21

20

19

15

14

13

12

11

10

9

Before

Therapy

Mean recall score as a function

of degree of hypnosis

Mean fear score as a function

of before-and-after therapy

After

Mean fear score

Mean recall score

No hypnosis

Hypnosis

FIGURE 12.7

Line graphs of the results

of the hypnosis study

and the phobia study

Describing the Relationship in a Two-Sample Experiment 279

280 CHAPTER 12 / The Two-Sample t-Test

From each graph, you can first discern the type—direction—of the relationship:

The hypnosis graph shows a positive linear relationship, and the phobia graph shows a

negative relationship. Further, recall that the regression line summarizes a relationship

by running through the center of the scatterplot. With only two conditions, the line

graph is the regression line. Therefore, we can envision the scatterplot in each graph

as being around the line, with participants’ data points located above and below each

mean’s data point. Finally, recall that we use the regression line to predict scores

based on . Therefore, for participants in a particular condition, we travel vertically to

the line and then horizontally to , predicting that they scored at the mean score for

that condition.

What’s missing is that we don’t know the nature of each relationship. Recall that

some relationships are stronger (more consistent) than others. Likewise, some inde-

pendent variables have a greater impact on a behavior than others. Researchers address

these issues by computing a measure of effect size.

Measuring Effect Size in the Two-Sample Experiment

An important statistic for describing the results of an experiment is called a measure of

effect size. The “effect” is from cause and effect, because in an experiment we assume

that changing the independent variable “causes” the dependent scores to change. (The

quotes are used because there’s always a chance that something else was the cause.)

However, not all independent variables will cause scores to change to the same degree,

so we need to know the influence that a particular variable has. Effect size indicates

the amount of influence that changing the conditions of the independent variable had

on dependent scores. Thus, for example, the extent to which changing hypnosis influ-

enced recall scores is the effect size of hypnosis.

The larger the effect size, the greater is the independent variable’s impact in deter-

mining participants’ scores. We want to study those variables that most influence the

behavior measured by these scores, so the larger the effect size, the more scientifi-

cally important the independent variable is. Remember that significant does not

mean important, but only that the sample relationship is unlikely to reflect sampling

error. Although a relationship must be significant to be potentially important, it can be

significant and still be unimportant. Thus, you should always compute a measure of

effect size for any significant result, because this is the only way to determine whether

your independent variable is important in influencing a behavior. In fact, the American

Psychological Association requires published research to report effect size.

REMEMBER The larger the effect size, the greater the influence that an inde-

pendent variable has on dependent scores and thus the more important the

variable is.

We will discuss two methods for measuring effect size. The first is to compute

Cohen’s d.

Effect Size Using Cohen’s d One way to describe the impact of an independent

variable is in terms of how big a difference we see between the means of our condi-

tions. For example, we saw that the presence/absence of hypnosis produced a differ-

ence in recall scores of 3. However, the problem is that we don’t know whether, in the

grand scheme of things, 3 is large, small, or in between. We need a frame of reference,

and here we use the estimated population standard deviation. Recall that the standard

deviation reflects the “average” amount that scores differ from the mean and from

Y

X

Y

each other. Individual scores always differ much more than their means, but this still

provides a frame of reference. For example, if individual scores differ by an “average”

of 20, then we know that many large differences among scores occur in this situation.

Therefore, a difference of 3 between two samples of such scores is not all that impres-

sive. However, say that scores differ by an “average” of only 5. Because smaller differ-

ences occur in this situation, a difference between conditions of 3 is more impressive.

Thus, we standardize the difference between our sample means by comparing it to

the population standard deviation. This is the logic behind the measure of effect size

known as Cohen’s d: It measures effect size as the magnitude of the difference between

the conditions, relative to the population standard deviation. We have two versions of

how it is computed.

1

Cohen, J. (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

For the independent-samples t-test, the difference between the conditions is meas-

ured as and the standard deviation comes from the square root of the pooled

variance. For our hypnosis study, the means were 23 and 20, and was 8.3, so

This tells us that the effect of changing our conditions was to change scores by an

amount that is slightly larger than one standard deviation.

For the related-samples t-test, the difference between the conditions is measured by

and the standard deviation comes from finding the square root of the estimated vari-

ance In our phobia study, and , so

Thus, the effect size of the therapy was 1.29.

We can interpret the above in two ways. First, the larger the absolute size of , the

larger the impact of the independent variable. In fact, Cohen

1

proposed the following

interpretations when is the neighborhood of the following amounts:

Values of d Interpretation of Effect Size

Small effect

Medium effect

Large effectd 5 .8

d 5 .5

d 5 .2

d

dds

d 5

D

2s

2

D

5

13.6

17.8

5

13.6

2.79

5 1.29

s

2

D

5 7.8D 513.61s

2

D

.2

D

d 5

X

1

2 X

2

2s

2

pool

5

23 2 20

18.3

5

13

2.88

5 1.04

s

2

pool

X

1

2 X

2

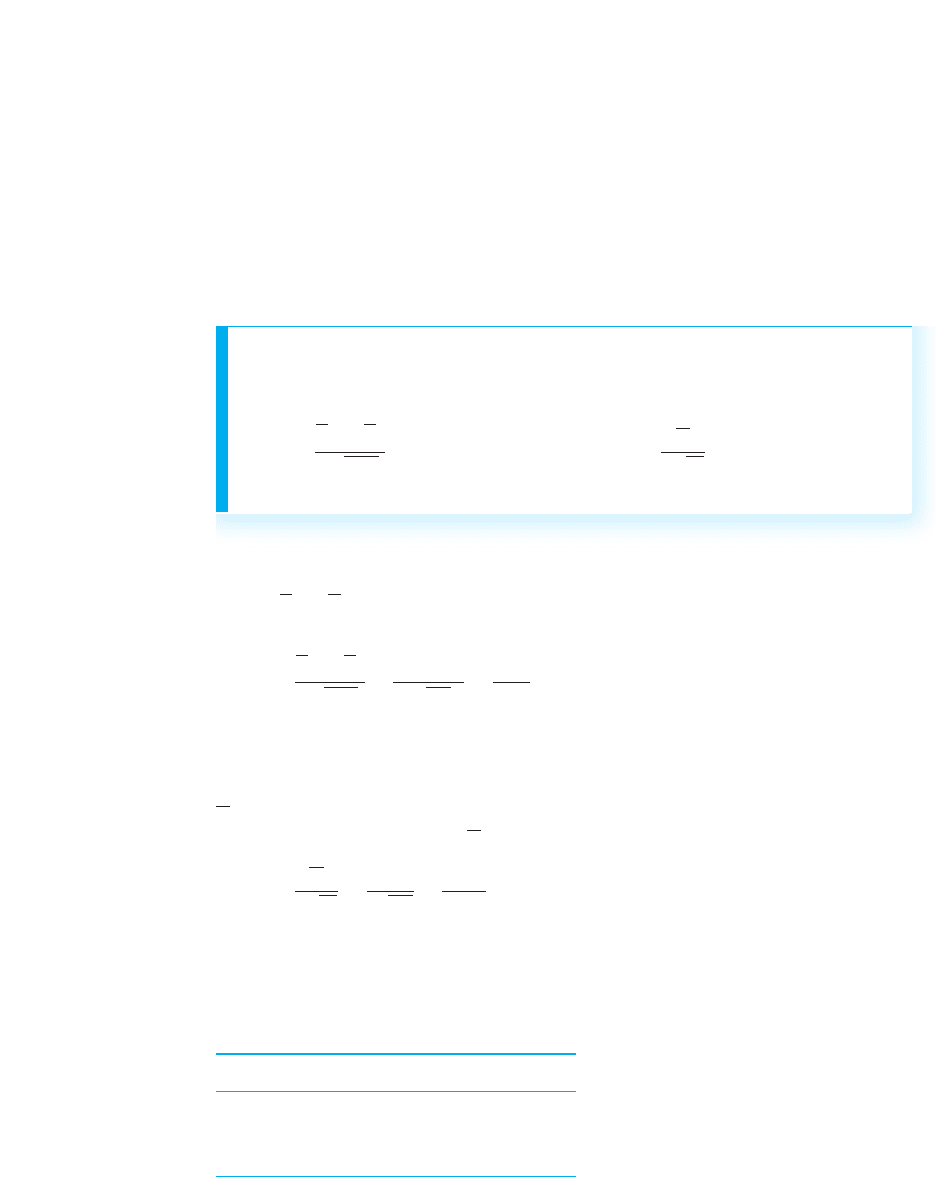

The formulas for Cohen’s d are:

Independent-samples t-test Related-samples t-test

d 5

D

3

s

2

D

d 5

X

1

2 X

2

3

s

2

pool

Describing the Relationship in a Two-Sample Experiment 281

282 CHAPTER 12 / The Two-Sample t-Test

Thus, above we found two very large effects. Second, we can compare the relative

size of different to determine the relative impact of a variable. Above, the for

hypnosis was 1.04, but for therapy it was 1.29. Therefore, the therapy manipulation

had a slightly larger impact. (Note: The difference between the conditions may pro-

duce a that some researchers use to indicate the direction the scores change.

Others think of as the amount of impact the independent variable has, which can-

not be negative.)

Another way to measure effect size is by computing the proportion of variance

accounted for.

Effect Size Using Proportion of Variance Accounted For This approach

measures effect size, not in terms of the size of the changes in scores but in terms of

how consistently the scores change. Here, a variable has a greater impact, the more it

“causes” everyone to behave in the same way, producing virtually the same score for

everyone in a particular condition. This then is an important variable, because by

itself, it pretty much controls the score (and behavior) that everyone exhibits. A vari-

able is more minor if it exhibits less control of a behavior and scores.

We measure this effect by measuring the “proportion of variance accounted for.”

Recall from Chapter 5 that variance reflects differences in scores and that when we

predict scores, we “account for variance.” In Chapter 8, we saw that the proportion

of variance accounted for was the proportional improvement achieved when we use

a relationship to predict scores compared to when we do not use the relationship to

predict scores. In an experiment, the scores we predict are the means of the condi-

tions. Thus, in an experiment, the proportion of variance accounted for is the pro-

portional improvement achieved when we use the mean of a condition as the

predicted score of participants tested in that condition compared to when we do not

use this approach. Put simply it is the extent to which individual scores in each con-

dition are close to the mean of the condition, so if we predict the mean for someone,

we are close to his or her actual score. When the independent variable has more con-

trol of a behavior, everyone in a condition will score more consistently. Then scores

will be closer to the mean, so we will have a greater improvement in accurately pre-

dicting the scores, producing a larger proportion of variance accounted for. On the

other hand, when the variable produces very different, inconsistent scores in each

condition, our ability to predict them is not improved by much, and so little of the

variance will be accounted for.

REMEMBER The larger the proportion of variance accounted for, the greater

the effect size of the independent variable in terms of consistently changing

scores, so the more important the variable is.

In Chapter 8, we saw that the computations for the proportion of variance

accounted for are performed by computing the squared correlation coefficient. For

the two-sample experiment, we compute a new correlation coefficient and then

square it. The squared point-biserial correlation coefficient indicates the propor-

tion of variance accounted for in a two-sample experiment. Its symbol is . This

can produce a proportion as a low as 0 (when the variable has no effect) to as high

as 1.0 (when the variable perfectly controls scores so that we can accurately predict

100% of them). In real research, however, a variable typically accounts for between

about 10% and 30% of the variance, with more than 30% being a very substantial

amount.

r

2

pb

d

1 or 2

dds

This formula is used with either the independent-samples or related-samples t-test. In

either case, start with your significant and square it. Then, for independent samples,

For related samples, .

In our hypnosis study, with , so,

Thus, on average, we are 22% closer to predicting participants’ recall scores when we

predict the mean of each hypnosis condition for them, compared to when we ignore this

relationship. Hypnosis is not of major importance here, because scores are not consis-

tently very close to the mean in each condition. Further, these inconsistent scores have

a cause, so other, hidden variables must be causing them (perhaps IQ, memory ability,

or motivation are operating). Therefore, hypnosis is only one of a number of variables

that play a role here, and, thus, it is only somewhat important in determining recall.

On the other hand, in the phobia study, and , so

Thus, the presence/absence of therapy accounts for 67% of the variance in fear scores.

This variable plays a substantial role in determining these scores. Further, fewer other

variables need to be considered in order to completely predict scores, so this is an

important relationship for understanding phobias and the therapy.

We also use the proportion of variance accounted for to compare the relationships from

different studies. Thus, the role of therapy in determining fear scores (at 67%) is about three

times larger than the role of hypnosis in determining recall scores (which was only 22%).

REMEMBER Compute effect size by computing or to determine the size

of the impact of an independent variable on dependent scores.

STATISTICS IN PUBLISHED RESEARCH: THE TWO-SAMPLE EXPERIMENT

Report the results of either two-sample t-test using the same format used previously,

but, remember, we also report the mean and standard deviation of each group, the con-

fidence interval, and effect size. Thus, a published report of our independent-samples

hypnosis study might say,

“The hypnosis group ( , ) produced significantly higher

recall scores than did the control group ( , ), with

( ) , < . The 95% confidence interval for the difference is 0.91

to 5.09. The effect size of the hypnosis manipulation was ”

For the phobia study, you would see a similar statement that included the means of

the raw fear scores in each condition.

r

2

pb

5 .22.

.05p 5 12.9330t

SD 5 2.74M 5 20.00

SD 5 3.00M 5 23.00

r

2

pb

d

r

2

pb

5

1t

obt

2

2

1t

obt

2

2

1 df

5

12.882

2

12.882

2

1 4

5

8.294

12.294

5 .67

df 5 4t

obt

512.88

r

2

pb

5

1t

obt

2

2

1t

obt

2

2

1 df

5

12.932

2

12.932

2

1 30

5

8.585

8.585 1 30

5

8.585

38.585

5 .22

df 5 30t

obt

512.93

df 5 N 2 1df 5 1n

1

2 121 1n

2

2 12

t

obt

The formula for computing is

r

2

pb

5

1t

obt

2

2

1t

obt

2

2

1 df

r

2

pb

Statistics in Published Research: The Two-Sample Experiment 283

Remember that one of your goals in this course is to learn when to use different statisti-

cal procedures. Obviously, you perform the independent-samples t-test if you’ve cre-

ated two independent samples and the related-samples t-test if you’ve created two

related samples.

In both procedures, if is not significant, consider whether you have sufficient

power. If is significant, then focus on the means from each condition so that you

summarize the typical score—and typical behavior—found in each condition. Use

effect size to gauge how big a role the independent variable plays in determining the

behaviors. Finally, interpret the relationship in terms of the underlying behaviors and

causes that it reflects. (This last step will become easier as you learn more about the

behavioral sciences in your other courses.)

Using the SPSS Appendix See Appendix B.6 to use SPSS to perform the independ-

ent-samples t-test or the related-samples t-test (but it is called the “paired-samples”

t-test). For either, the program indicates the at which is significant, but for a

two-tailed test only. It also computes the descriptive statistics for each condition and

automatically computes the confidence interval for either or The program

does not compute or

CHAPTER SUMMARY

1. Two samples are independent when participants are randomly selected for each,

without regard to who else has been selected, and each participant is in only one

condition.

2. The independent-samples t-test requires (a) two independent samples,

(b) normally distributed interval or ratio scores, and (c) homogeneous variance.

3. Homogeneity of variance means that the variances in the populations being

represented are equal.

4. The confidence interval for the difference between two ms contains a range of

differences between two , one of which is likely to be represented by the

difference between our two sample means.

5. Two samples are related either when we match each participant in one condition

to a participant in the other condition, or when we use repeated measures of one

group of participants tested under both conditions.

6. The confidence interval for m contains a range of values of , any one of which

is likely to be represented by the sample’s .

7. The power of a two-sample t-test increases with (a) larger differences in scores

between the conditions, (b) smaller variability of scores within each condition,

and (c) larger The related-samples t-test is more powerful than the

independent-samples t-test.

8. Effect size indicates the amount of influence that changing the conditions of the

independent variable had on the dependent scores.

ns

D

DD

s

r

2

pb

.d

D

.

1

2

2

t

obt

t

obt

t

obt

PUTTING IT

ALL TOGETHER

284 CHAPTER 12 / The Two-Sample t-Test

9. Cohen’s measures effect size as the magnitude of the difference between the

conditions.

10. The proportion of variance accounted for (computed as ) measures effect

size as the consistency of scores produced within each condition. The larger the

proportion, the more accurately the mean of a condition predicts individual scores

in that condition.

r

2

pb

d

KEY TERMS

Cohen’s 281

Confidence interval for 277

confidence interval for the difference

between two 269

effect size 280

homogeneity of variance 262

independent samples 262

independent-samples t-test 262

matched-samples design 271

pooled variance 265

related samples 271

s

D

d

r

2

pb

ds

D

s

2

D

Ds

X

1

2X

2

s

2

pool

Nn

related-samples t-test 271

repeated-measures design 271

sampling distribution of differences

between the means 263

sampling distribution of mean

differences 274

standard error of the difference 265

standard error of the mean

difference 275

squared point-biserial correlation

coefficient 282

REVIEW QUESTIONS

(Answers for odd-numbered questions are in Appendix D.)

1. A scientist has conducted a two-sample experiment. (a) What two parametric

procedures are available to him? (b) What is the deciding factor for selecting

between them?

2. How do you create independent samples?

3. (a) What are the two ways to create related samples? (b) What other assumptions

must be met before using either two-sample t-test?

4. What is homogeneity of variance?

5. (a) What is ? (b) What is ? (c) What is the difference between and ?

6. All other things being equal, should you create a related-samples or an

independent-samples design? Why?

7. What does the confidence interval for indicate?

8. What does a confidence interval for the difference between two

indicate?

9. (a) What does effect size indicate? (b) What does indicate? (c) What does

indicate?

10. (a) What is the final step when completing an experiment? (b) Why is effect size

useful at this stage?

11. Foofy obtained a statistically significant two-sample . What three things should

she do to complete her analysis?

t

obt

r

2

pb

d

s

D

Nns

D

s

X

1

2X

2

Review Questions 285

286 CHAPTER 12 / The Two-Sample t-Test

APPLICATION QUESTIONS

12. For the following, which type of t-test is required? (a) Studying the effects of a

memory drug on Alzheimer’s patients, testing a group of patients before and after

administration of the drug. (b) Studying whether men and women rate the persua-

siveness of an argument delivered by a female speaker differently. (c) The study

described in part (b), but with the added requirement that for each man of a partic-

ular age, there is a woman of the same age.

13. We study the relationship between hot or cold baths and the amount of relaxation

they produce. The relaxation scores from two independent samples are

Sample 1 (hot): , ,

Sample 2 (cold): , ,

(a) What are and ? (b) Compute (c) With , what is ?

(d) What should we conclude about this relationship? (e) Compute the

confidence interval for the difference between the (f) Using our two

approaches, how big of an effect does bath temperature have on relaxation?

(g) Describe how you would graph these results.

14. We investigate if a period of time feels longer or shorter when people are bored

compared to when they are not bored. Using independent samples, we obtain

these estimates of the time period (in minutes):

Sample 1 (bored): , ,

Sample 2 (not bored): , ,

(a) What are and ? (b) Compute (c) With , what is ?

(d) What should the researcher conclude about this relationship? (e) Compute

the confidence interval for the difference between the (f) Using our two

approaches, how important is boredom in determining how quickly time seems

to pass?

15. A researcher asks if people score higher or lower on a questionnaire measuring

their well-being when they are exposed to much sunshine compared to when

they’re exposed to little sunshine. A sample of 8 people is measured under both

levels of sunshine and produces these well-being scores:

Low: 14 13 17 15 18 17 14 16

High: 18 12 20 19 22 19 19 16

(a) Subtracting low from high, what are and ? (b) Compute

(c) With , what do you conclude about this study? (d) Compute the

appropriate confidence interval. (e) What is the predicted well-being score for

someone when tested under low sunshine? Under high sunshine? (f) On average,

how much more accurate are these predictions than if you did not know how

much sunshine people experience? (g) How scientifically important are these

results?

16. A researcher investigates whether classical music is more or less soothing to air-

traffic controllers than modern music. She plays a classical selection to one group

and a modern selection to another. She gives each person an irritability question-

naire and obtains the following:

Sample A (classical): , ,

Sample B (modern): , , s

2

X

5 11.6X 5 17.21n 5 6

s

2

X

5 8.4X 5 14.69n 5 6

5 .05

t

obt

.H

a

H

0

s.

t

crit

5 .05t

obt

H

a

H

0

n 5 34s

2

X

5 14.6X 5 9.0

n 5 28s

2

X

5 10.22X 5 14.5

s.

t

crit

5 .05t

obt

H

a

H

0

n 5 15s

2

X

5 24.6X 5 39

n 5 15s

2

X

5 22.79X 5 43

(a) Subtracting , what are and ? (b) What is ? (c) With ,

are the results significant? (d) Report the results using the correct format.

(e) What should she conclude about the relationship in nature between type of

music and irritability? (f) What other statistics should be computed? (g) What

statistical flaw is likely in the experiment?

17. We predict that children exhibit more aggressive acts after watching a violent

television show. The scores for ten participants before and after watching the

show are

Sample 1 (After) Sample 2 (Before)

54

66

43

42

74

31

20

10

45

32

(a) Subtracting before from after, what are and ? (b) Compute

(c) With , what is ? (d) What should the researcher conclude about

this relationship? (e) Compute the appropriate confidence interval. (f) How

large is the effect of violence in terms of the difference it produces in

aggression scores?

18. You investigate whether the older or younger male in pairs of brothers tends to be

more extroverted. You obtain the following extroversion scores:

Sample 1 (Younger) Sample 2 (Older)

10 18

11 17

18 19

12 16

15 15

13 19

19 13

15 20

(a) What are and ? (b) Compute (c) With , what is ? (d) What

should you conclude about this relationship? (e) Which of our approaches should

we use to determine if this a scientifically important relationship?

19. A rather dim student proposes testing the conditions of “male” and “female” using

a repeated-measures design. What’s wrong with this idea?

20. With and , a significant independent-samples was .

How would you report this in the literature?

21. An experimenter investigated the effects of a sensitivity training course on a

policeman’s effectiveness at resolving domestic disputes (using independent

14.55t

obt

df 5 40␣ 5 .05

t

crit

␣ 5 .05t

obt

H

a

H

0

t

crit

␣ 5 .05

t

obt

H

a

H

0

␣ 5 .05t

obt

H

a

H

0

A 2 B

Application Questions 287