Heiman G. Basic Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

128 CHAPTER 6 / z-Scores and the Normal Curve Model

the standard deviation. Here, however, we are measuring how far the sample mean

score is from the mean of the sampling distribution, measured using the “standard devi-

ation” called the standard error.

For the sample from Prunepit U, , , and , so

Thus, a sample mean of 520 has a z-score of on the SAT sampling distribution of

means that occurs when is 25.

Another Example Combining All of the Above Say that over at Podunk U, a

sample of 25 SAT scores produced a mean of 460. With and , we’d

again envision the SAT sampling distribution we saw back in Figure 6.8. To find the

z-score, first, compute the standard error of the mean :

Then find z:

The Podunk sample has a z-score of on the sampling distribution of SAT means.

Describing the Relative Frequency of Sample Means

Everything we said previously about a z-score for an individual score applies to a

z-score for a sample mean. Thus, because our original Prunepit mean has a z-score

of , we know that it is above the of the sampling distribution by an amount

equal to the “average” amount that sample means deviate above . Therefore,

we know that, although they were not stellar, our Prunepit students did outperform a

substantial proportion of comparable samples. Our sample from Podunk U, however,

has a z-score of , so its mean is very low compared to other means that occur in

this situation.

And here’s the nifty part: Because the sampling distribution of means always forms

at least an approximately normal distribution, if we transformed all of the sample

means into z-scores, we would have a roughly normal z-distribution. Recall that the

standard normal curve is our model of any roughly normal z-distribution. Therefore,

we can apply the standard normal curve to a sampling distribution.

REMEMBER The standard normal curve model and the z-table can be used

with any sampling distribution, as well as with any raw score distribution.

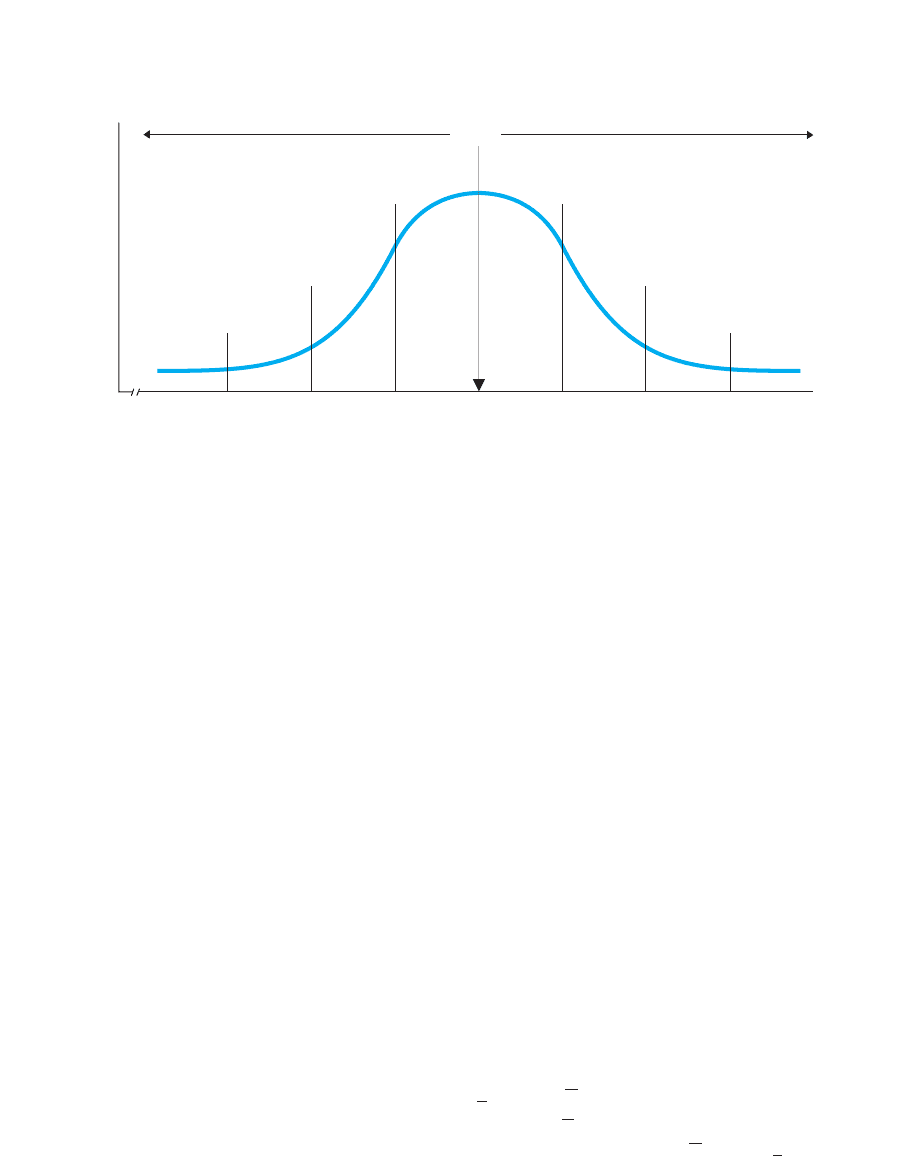

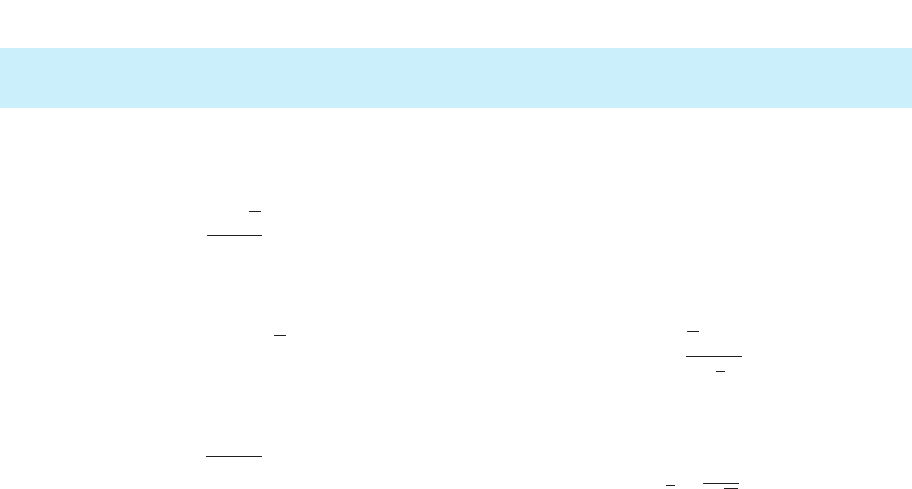

Figure 6.9 shows the standard normal curve applied to our SAT sampling distribu-

tion of means. Once again, larger positive or negative z-scores indicate that we are far-

ther into the tails of the distribution, and the corresponding proportions are the same

proportions we used to describe raw scores. Therefore, as we did then, we can use the

standard normal curve (and the z-table) to determine the proportion of the area under

any part of the curve. This proportion is also the expected relative frequency of the cor-

responding sample means in that part of the sampling distribution.

22

11

22

z 5

X 2

σ

X

5

460 2 500

20

5

240

20

522

σ

X

5

σ

X

1N

5

100

125

5

100

5

5 20

1σ

X

2

σ

X

5 100 5 500

N

11

z 5

X 2

σ

X

5

520 2 500

20

5

120

20

511.00

σ

X

5 20 5 500X 5 520

Using z-Scores to Describe Sample Means 129

For example, the Prunepit sample has a z of . As in Figure 6.9 (and from col-

umn B of the z-table), of all scores fall between the mean and z of on any

normal distribution. Therefore, of all SAT sample means are expected to fall

between the and the sample mean at a z of . Because here the is 500 and a z

of is at the sample mean of 520, we can also say that of all SAT sample

means are expected to be between 500 and 520 (when is 25).

However, say that we asked about sample means above our sample mean. As in

column C of the z-table, above a z of is .1587 of the distribution. Therefore, we

expect that .1587 of SAT sample means will be above 520. Similarly, the Podunk U

sample mean of 460 has a z of . As in column B of the z-table, a total of of

a distribution falls between the mean and this z-score. Therefore, we expect .4772 of

SAT means to be between 500 and 460, with (as in column C) only of the

means below 460.

We can use this same procedure to describe sample means from any normally dis-

tributed variable.

Summary of Describing a Sample Mean with a z-Score

To describe a sample mean from any raw score population, follow these steps:

1. Envision the sampling distribution of means (or better yet, draw it) as a normal

distribution with a equal to the of the underlying raw score population.

2. Locate the sample mean on the sampling distribution, by computing its z-score.

a. Using the of the raw score population and your sample , compute the stan-

dard error of the mean:

b. Compute z by finding how far your is from the of the sampling

distribution, measured in standard error units:

3. Use the z-table to determine the relative frequency of scores above or below this

z-score, which is the relative frequency of sample means above or below your

mean.

z 5 1X 2 2>σ

X

X

σ

X

5 σ

X

>1N

Nσ

X

.0228

.477222

11

N

.341311

11

.3413

11.3413

11

μ

.50

.0013 .0215 .1359 .3413 .3413 .1359 .0215 .0013

.50

SAT means

z-scores

+1

–3 –2 –1 0

+2 +3

520

440 460 480 500

540 560

f

FIGURE 6.9

Proportions of the standard normal curve applied to the sampling distribution of SAT means

130 CHAPTER 6 / z-Scores and the Normal Curve Model

PUTTING IT ALL

TOGETHER

The most important concept for you to understand is that any normal distribution

of scores can be described using the standard normal curve model and z-scores. To

paraphrase a famous saying, a normal distribution is a normal distribution is a normal

distribution. Any normal distribution contains the same proportions of the total area

under the curve between z-scores. Therefore, whenever you are discussing individual

scores or sample means, think z-scores and use the previous procedures.

You will find it very beneficial to sketch the normal curve when working on z-score

problems. For raw scores, label where the mean is and about where the specified

raw score or z-score is, and identify the area that you seek. At the least, this will

instantly tell you whether you seek information from column B or column C in the

z-table. For sample means, first draw and identify the raw score population that the

bored statistician would sample, and then draw and label the above parts of the sam-

pling distribution.

By the way, what was Biff’s percentile?

Using the SPSS Appendix As described in Appendix B.3, SPSS will simultaneously

transform an entire sample of scores into z-scores. We enter in the raw scores and SPSS

produces a set of z-scores in a column next to where we typed our raw scores.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

1. The relative standing of a score reflects a systematic evaluation of the score relative

to a sample or population. A z-score indicates a score’s relative standing by indicat-

ing the distance the score is from the mean when measured in standard deviations.

■

To describe a sample mean, compute its z-score and

use the z-table to determine the relative frequency

of sample means above or below it.

MORE EXAMPLES

On a test, , , and our . What

proportion of sample means will be above

First, compute the standard error of the mean :

Next, compute z:

Finally, examine the z-table: The area above this z is

the upper tail of the distribution, so from column C is

0.0668. This is the proportion of sample means

expected to be above a mean of 103.

z 5

X

2

σ

X

5

103 2 100

2

5

13

2

511.5

σ

X

5

σ

X

1N

5

16

164

5

16

8

5 2

1σ

X

2

X 5 103?

N 5 64σ

X

5 16 5 100

For Practice

A population of raw scores has and

our and

1. The of the sampling distribution here

equals ____.

2. The symbol for the standard error of the mean is

____, and here it equals ____.

3. The z-score for a sample mean of 80 is ____.

4. How often will sample means between 75 and 80

occur in this situation?

Answers

1. 75

2.

3.

4. From Column B: .4884 of the Time

z 5 180 2 752>2.20 512.27

σ

X

; 22>1100 5 2.20

X 5 80N 5 100

σ

X

5 22; 5 75

A QUICK REVIEW

Review Questions 131

2. A positive z-score indicates that the raw score is above the mean; a negative

z-score indicates that the raw score is below the mean. The larger the absolute

value of z, the farther the raw score is from the mean, so the less frequently the

z-score and raw score occur.

3. z-scores are used to describe the relative standing of raw scores, to compare raw

scores from different variables, and to determine the relative frequency of raw

scores.

4. A z-distribution is produced by transforming all raw scores in a distribution into

z-scores.

5. The standard normal curve is a perfect normal z-distribution that is our model

of the z-distribution that results from data that are approximately normally

distributed, interval or ratio scores.

6. The sampling distribution of means is the frequency distribution of all possible

sample means that occur when an infinite number of samples of the same size

N are randomly selected from one raw score population.

7. The central limit theorem shows that in a sampling distribution of means (a) the

distribution will be approximately normal, (b) the mean of the sampling distribu-

tion will equal the mean of the underlying raw score population, and (c) the

variability of the sample means is related to the variability of the raw scores.

8. The true standard error of the mean is the standard deviation of the sampling

distribution of means.

9. The location of a sample mean on the sampling distribution of means can be

described by calculating a z-score. Then the standard normal curve model can be

applied to determine the expected relative frequency of the sample means that are

above or below the z-score.

10. Biff’s percentile was 99.87.

1σ

X

2

KEY TERMS

central limit theorem 125

relative standing 110

sampling distribution of means 125

standard error of the mean 126

; z σ

X

standard normal curve 118

standard score 116

z-distribution 115

z-score 111

REVIEW QUESTIONS

(Answers for odd-numbered questions are in Appendix D.)

1. (a) What does a z-score indicate? (b) Why are z-scores important?

2. On what two factors does the size of a z-score depend?

3. What is a z-distribution?

4. What are the three general uses of z-scores with individual raw scores?

132 CHAPTER 6 / z-Scores and the Normal Curve Model

5. (a) What is the standard normal curve? (b) How is it applied to a set of data?

(c) What three criteria should be met for it to give an accurate description of the

scores in a sample?

6. (a) What is a sampling distribution of means? (b) When is it used? (c) Why is it

useful?

7. What three things does the central limit theorem tell us about the sampling

distribution of means? (b) Why is the central limit theorem so useful?

8. What does the standard error of the mean indicate?

9. (a) What are the steps for using the standard normal curve to find a raw score’s

relative frequency or percentile? (b) What are the steps for finding the raw score

that cuts off a specified relative frequency or percentile? (c) What are the steps

for finding a sample mean’s relative frequency?

APPLICATION QUESTIONS

10. In an English class last semester, Foofy earned a ). Her

friend, Bubbles, in a different class, earned a ). Should

Foofy be bragging about how much better she did? Why?

11. Poindexter received a 55 on a biology test and a 45 on a philosophy

test . He is considering whether to ask his two professors to curve the

grades using z-scores. (a) Does he want the to be large or small in biology?

Why? (b) Does he want the to be large or small in philosophy? Why?

12. Foofy computes z-scores for a set of normally distributed exam scores. She obtains

a z-score of for 8 out of 20 of the students. What do you conclude?

13. For the data,

9510791011812769

(a) Compute the z-score for the raw score of 10. (b) Compute the z-score for the

raw score of 6.

14. For the data in question 13, find the raw scores that correspond to the following:

(a) ; (b)

15. Which z-score in each of the following pairs corresponds to the lower raw

score? (a) ; (b)

(c) (d)

16. For each pair in question 15, which z-score has the higher frequency?

17. In a normal distribution, what proportion of all scores would fall into each of the

following areas? (a) Between the mean and ; (b) below

(c) between and ; (d) above and below .

18. For a distribution in which , , and : (a) What is the rela-

tive frequency of scores between 76 and the mean? (b) How many participants are

expected to score between 76 and the mean? (c) What is the percentile of someone

scoring 76? (d) How many subjects are expected to score above 76?

19. Poindexter may be classified as having a math dysfunction—and not have to take

statistics—if he scores below the 25th percentile on a diagnostic test. The of the

test is 75 . Approximately what raw score is the cutoff score for him to

avoid taking statistics?

20. For an IQ test, we know the population and the . We are

interested in creating the sampling distribution when . (a) What does thatN 5 64

σ

X

5 16 5 100

1σ

X

5 102

N 5 500S

X

5 16X 5 100

21.96z 511.96z 512.75z 521.25

z 522.30;z 511.89

z 5 0.0 or z 522.0.z 52.70 or z 52.20;

z 522.8 or z 521.7;z 511.0 or z 512.3

z 520.48.z 511.22

23.96

S

X

S

X

1X 5 502

1X 5 502

60 1X 5 50, S

X

5 4

76 1X 5 85, S

X

5 10

Integration Questions 133

sampling distribution of means show? (b) What is the shape of the distribution of

IQ means and the mean of the distribution? (c) Calculate for this distribution.

(d) What is your answer in part (c) called, and what does it indicate? (e) What is

the relative frequency of sample means above 101.5?

21. Someone has two job offers and must decide which to accept. The job in City A

pays $47,000 and the average cost of living there is $65,000, with a standard

deviation of $15,000. The job in City B pays $70,000, but the average cost of

living there is $85,000, with a standard deviation of $20,000. Assuming salaries

are normally distributed, which is the better job offer? Why?

22. Suppose you own shares of a company’s stock, the price of which has risen so

that, over the past ten trading days, its mean selling price is $14.89. Over the

years, the mean price of the stock has been $10.43 You wonder if

the mean selling price over the next ten days can be expected to go higher. Should

you wait to sell, or should you sell now?

23. A researcher develops a test for selecting intellectually gifted children, with a

of 56 and a of 8. (a) What percentage of children are expected to score below

60? (b) What percentage of scores will be above 54? (c) A gifted child is

defined as being in the top 20%. What is the minimum test score needed to qual-

ify as gifted?

24. Using the test in question 23, you measure 64 children, obtaining a of 57.28.

Slug says that because this is so close to the of 56, this sample could hardly

be considered gifted. (a) Perform the appropriate statistical procedure to

determine whether he is correct. (b) In what percentage of the top scores is this

sample mean?

25. A researcher reports that a sample mean produced a relatively large positive or

negative z score. (a) What does this indicate about that mean’s relative frequency?

(b) What graph did the researcher examine to make this conclusion? (c) To what

was the researcher comparing his mean?

INTEGRATION QUESTIONS

26. What does a relatively small standard deviation indicate about the scores in a

sample? (b) What does this indicate about how accurately the mean summarizes

the scores. (c) What will this do to the z-score for someone who is relatively far

from the mean? Why? (Chs. 5, 6)

27. (a) With what type of data is it appropriate to compute the mean and standard

deviation? (b) With what type of data is it appropriate to compute z-scores?

(Chs. 4, 5, 6)

28. (a) What is the difference between a proportion and a percent? (b) What are the

mathematical steps for finding a specified percent of ? (Ch. 1)

29. (a) We find that .40 of a sample of 500 people score above 60. How many people

scored above 60? (b) In statistical terms, what are we asking about a score when

we ask how many people obtained the score? (c) We find that 35 people out of

50 failed an exam. What proportion of the class failed? (d) What percentage

of the class failed? (Chs. 1, 3)

30. What is the difference between the normal distributions we’ve seen in previous

chapters and (a) a z-distribution and (b) a sampling distribution of means?

(Chs. 3, 6)

N

X

X

σ

X

1σ

X

5 $5.60.2

σ

X

134 CHAPTER 6 / z-Scores and the Normal Curve Model

■ ■ ■ SUMMARY OF

FORMULAS

1. The formula for transforming a raw score in a

sample into a z-score is

2. The formula for transforming a z-score in a

sample into a raw score is

3. The formula for transforming a raw score in a

population into a z-score is

z 5

X 2

σ

X

X 5 1z21S

X

21 X

z 5

X 2 X

S

X

4. The formula for transforming a z-score in a

population into a raw score is

5. The formula for transforming a sample mean

into a z-score on the sampling distribution of

means is

6. The formula for the true standard error of the

mean is

σ

X

5

σ

X

1N

z 5

X

2

σ

X

X 5 1z21σ

X

21

Recall that in research we want to not only demonstrate a relationship but also describe

and summarize the relationship. The one remaining type of descriptive statistic for us

to discuss is used to summarize relationships, and it is called the correlation coefficient.

In the following sections, we’ll consider when these statistics are used and what they

tell us. Then we’ll see how to compute the two most common versions of the correla-

tion coefficient. First, though, a few more symbols.

NEW STATISTICAL NOTATION

Correlational analysis requires scores from two variables. Then, stands for the scores

on one variable, and stands for the scores on the other variable. Usually each pair of

X–Y scores is from the same participant. If not, there must be a rational system for

pairing the scores (for example, pairing the scores of roommates). Obviously we must

have the same number of and scores.

We use the same conventions for that we’ve previously used for . Thus, is the

sum of the scores, is the sum of the squared scores, and is the squared

sum of the scores.Y

1©Y 2

2

Y©Y

2

Y

©YXY

YX

Y

X

135

The Correlation Coefficient

7

GETTING STARTED

To understand this chapter, recall the following:

■

From Chapter 2, that in a relationship, particular scores tend to occur with a

particular , a more consistent relationship is “stronger,” and we can use

someone’s to predict what his/her will be.

■

From Chapter 5, that greater variability indicates a greater variety of scores is

present and so greater variability produces a weaker relationship. Also that the

phrase “accounting for variance” refers to accurately predicting scores.

Your goals in this chapter are to learn

■

The logic of correlational research and how it is interpreted.

■

How to read and interpret a scatterplot and a regression line.

■

How to identify the type and strength of a relationship.

■

How to interpret a correlation coefficient.

■

When to use the Pearson r and the Spearman .

■

The logic of inferring a population correlation based on a sample correlation.

r

S

Y

YX

X

Y

You will also encounter three other notations. First, indicates to first find

the sum of the and the sum of the and then multiply the two sums together. Sec-

ond, , called the sum of the cross products, says to first multiply each score in a

pair times its corresponding score and then sum all of the resulting products.

REMEMBER says to multiply the sum of times the sum of .

says to multiply each times its paired and then sum the products.

Finally, stands for the numerical difference between the and scores in a pair,

which you find by subtracting one from the other.

Now, on to the correlation coefficient.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO KNOW ABOUT CORRELATION COEFFICIENTS?

Recall that a relationship is present when, as the scores increase, the corresponding

scores change in a consistent fashion. Whenever we find a relationship, we then want

to know its characteristics: What pattern is formed, how consistently do the scores

change together, and what direction do the scores change? The best—and easiest—way

to answer these questions is to compute a correlation coefficient. The correlation

coefficient is the descriptive statistic that, in a single number, summarizes and de-

scribes the important characteristics of a relationship. The correlation coefficient quan-

tifies the pattern in a relationship, examining all X–Y pairs at once. No other statistic

does this. Thus, the correlation coefficient is important because it simplifies a complex

relationship involving many scores into one, easily interpreted statistic. Therefore, in

any research where a relationship is found, always calculate the appropriate correlation

coefficient.

As a starting point, the correlation coefficients discussed in this chapter are most

commonly associated with correlational research.

UNDERSTANDING CORRELATIONAL RESEARCH

Recall that a common research design is the correlational study. The term correlation

is synonymous with relationship, so in a correlational design we examine the rela-

tionship between variables. (Think of correlation as meaning the shared, or “co,” re-

lationship between the variables.) The relationship can involve scores from virtually

any variable, regardless of how we obtain them. Often we use a questionnaire or

observe participants, but we may also measure scores using any of the methods used

in experiments.

Recall that correlational studies differ from experiments in terms of how we

demonstrate the relationship. For example, say that we hypothesize that as people

drink more coffee they become more nervous. To demonstrate this in an experiment,

we might assign some people to a condition in which they drink 1 cup of coffee, as-

sign others to a 2-cup condition and assign still others to a 3-cup condition. Then we

would measure participants’ nervousness and see if more nervousness is related to

more coffee. Notice that, by creating the conditions, we (the researchers) determine

each participant’s score because we decide whether their “score” will be 1, 2, or 3

cups on the coffee variable.

In a correlational design, however, we do not manipulate any variables, so we do not

determine participants’ scores. Rather, the scores on both variables reflect an amountX

X

YX

YXD

YX©XY

YX1©X21©Y2

Y

X©XY

YsXs

1©X21©Y2

136 CHAPTER 7 / The Correlation Coefficient

or category of a variable that a participant has already experienced. Therefore, we

simply measure the two variables and describe the relationship that is present. Thus,

we might ask participants the amount of coffee they have consumed today and measure

how nervous they are.

Recognize that computing a correlation coefficient does not create a correlational

design: It is the absence of manipulation that creates the design. In fact, in later chapters

we will compute correlation coefficients in experiments. However, correlation coeffi-

cients are most often used as the primary descriptive statistic in correlational research,

and you must be careful when interpreting the results of such a design.

Drawing Conclusions from Correlational Research

People often mistakenly think that a correlation automatically indicates causality. How-

ever, recall from Chapter 2 that the existence of a relationship does not necessarily

indicate that changes in cause the changes in . A relationship—a correlation—can

exist, even though one variable does not cause or influence the other. Two requirements

must be met to confidently conclude that causes .

First, must occur before . However, in correlational research, we do not always

know which factor occurred first. For example, if we simply measure the coffee drink-

ing and nervousness of some people after the fact, it may be that participants who were

already more nervous then tended to drink more coffee. Therefore, maybe greater nerv-

ousness actually caused greater coffee consumption. In any correlational study, it is

possible that causes .

Second, must be the only variable that can influence . But, in correlational

research, we do little to control or eliminate other potentially causal variables. For exam-

ple, in the coffee study, some participants may have had less sleep than others the night

before testing. Perhaps the lack of sleep caused those people to be more nervous and to

drink more coffee. In any correlational study, some other variable may cause both

and to change. (Researchers often refer to this as “the third variable problem.”)

Thus, a correlation by itself does not indicate causality. You must also consider the

research method used to demonstrate the relationship. In experiments we apply the in-

dependent variable first, and we control other potential causal variables, so experiments

provide better evidence for identifying the causes of a behavior.

Unfortunately, this issue is often lost in the popular media, so be skeptical the next

time some one uses correlation and cause together. The problem is that people often

ignore that a relationship may be a meaningless coincidence. For example, here’s a re-

lationship: As the number of toilets in a neighborhood increases, the number of crimes

committed in that neighborhood also increases. Should we conclude that indoor plumb-

ing causes crime? Of course not! Crime tends to occur more frequently in the crowded

neighborhoods of large cities. Coincidentally, there are more indoor toilets in such

neighborhoods.

The problem is that it is easy to be trapped by more mysterious relationships. Here’s

a serious example: A particular neurological disease occurs more often in the colder,

northern areas of the United States than in the warmer, southern areas. Do colder tem-

peratures cause this disease? Maybe. But, for all the reasons given above, the mere ex-

istence of this relationship is not evidence of causality. The north also has fewer sunny

days, burns more heating oil, and differs from the south in many other ways. One of

these variables might be the cause, while coincidentally, colder temperatures are also

present.

Thus, a correlational study is not used to infer a causal relationship. It is possible that

changes in might cause changes in , but we will have no convincing evidence ofYX

Y

X

YX

XY

YX

YX

YX

Understanding Correlational Research 137