Hassani S. Mathematical Methods: For Students of Physics and Related Fields

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

92 Integration: Formalism

3.3.1 Reduction to Single Integrals

Most integrals encountered in physics are multidimensional. Thus, it is impor-

tant to know how to evaluate multiple integrals. Let us concentrate on triple

integration, and for definiteness, let us assume that the integration variables

are actual coordinates in a Cartesian coordinate system.

10

The most general

integral, namely Equation (3.4), will then be rewritten as

##

Ω

f(r, r

) dQ(r

) ≡

##

Ω

f(r,x

,y

,z

) dQ(x

,y

,z

)

=

##

V

#

f(r,x

,y

,z

)ρ

Q

(x

,y

,z

) dx

dy

dz

,

where we have reexpressed dQ in terms of some density. The region of integra-

tion V may have to be divided into a number of other more easily integrable

regions. However, in most applications, by a good choice of the order of inte-

gration, one can avoid such division. Let us assume that by integrating the

z

variable first, we will not need to divide the region. The z

integration is a

single integral and is done by keeping x

and y

constant. To find the upper

limit of this integral, we pick an arbitrary point

11

in the region, fix its first

two coordinates, move “up” until we hit the boundary of V at a point. The

third coordinate of this boundary point,whenexpressedintermsofx

and

y

, will be the upper limit of the z

integration. The lower limit is obtained

similarly. In most cases, V is bounded by a given upper surface of the form

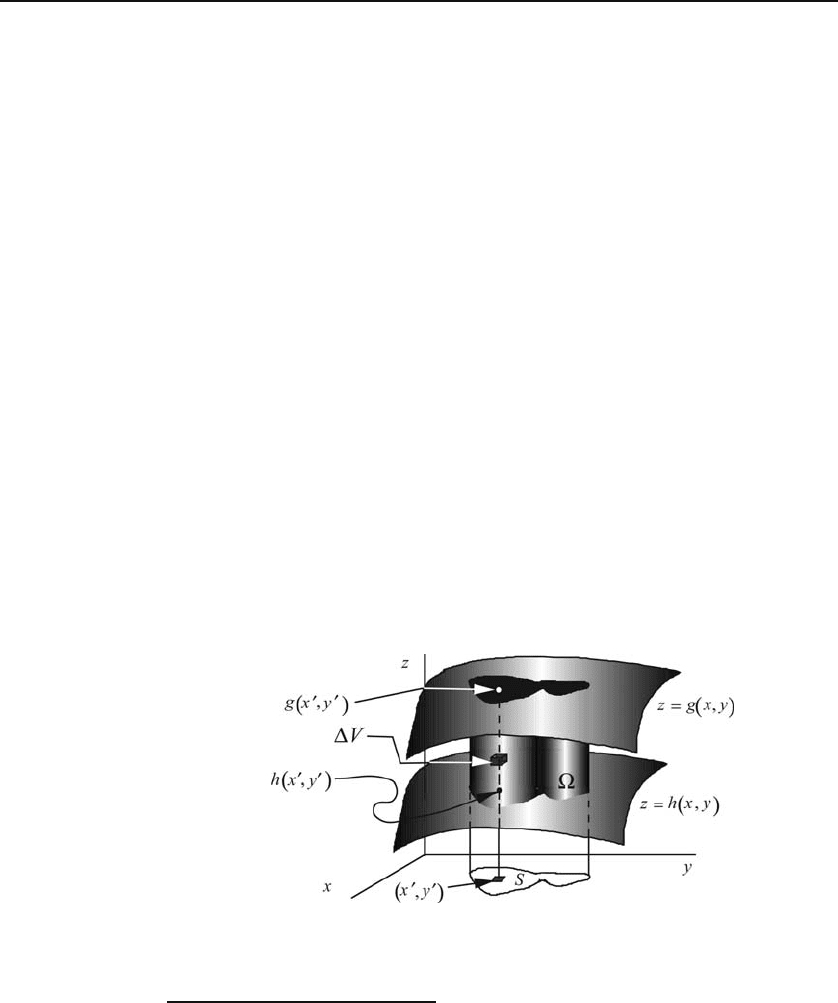

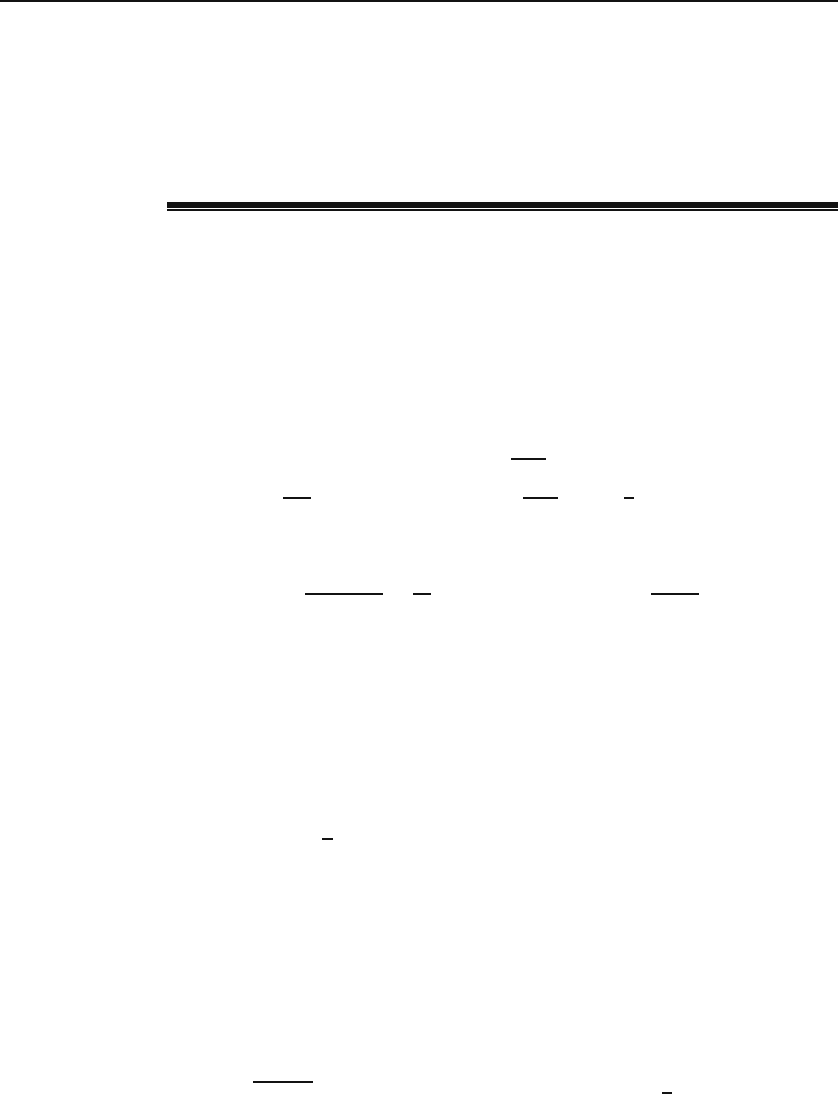

z = g(x, y), and a lower surface of the form z = h(x, y) as shown in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: The limits of the first integration of a triple integral are defined by two

surfaces.

10

Recall that the integration variables, although considered as “coordinates of a point,”

need not be an actual geometric point in space. They could, for instance, be a set of

thermodynamical variables describing a thermodynamical system.

11

A common mistake at this stage is to pick a special point. To make sure that you have

picked an arbitrary point, go through the following process using the point chosen, then

pick a different point, go through the process and see if you obtain the same result for the

upper and lower limits of the integral.

3.3 Guidelines for Calculating Integrals 93

Thus, since the first two coordinates of the boundary points are x

and y

,

the upper limit will be g(x

,y

) and the lower limit will be h(x

,y

). We thus

write the integral as

##

Ω

f(r, r

) dQ(r

)=

##

S

dx

dy

#

g(x

,y

)

h(x

,y

)

f(r,x

,y

,z

)ρ

Q

(x

,y

,z

) dz

,

where S is the projection of V on the xy-plane. For S to be useful, it must

have the following property: Every point of the upper and lower boundaries of

V has one and only one image in S, and no two points of the upper (or lower)

boundary project onto the same point in S. If this property is not fulfilled,

then we must choose another coordinate as our first integration variable, or,

if this does not work, divide the region of integration into pieces for each one

of which this property holds.

Let us assume that the property holds for S, and that we can do the

integral in z

. The result of this integration is a complete elimination of the

z

-coordinate and the reduction of the triple integral down to a double integral.

To be more specific, assume that the primitive of the integrand, as a function

of z

,isF (r,x

,y

,z

), i.e., that

∂F

∂z

= f (r,x

,y

,z

)ρ

Q

(x

,y

,z

).

Then, the z

integration yields

#

g(x

,y

)

h(x

,y

)

f(r,x

,y

,z

)ρ

Q

(x

,y

,z

) dz

= F (r,x

,y

,g(x

,y

)) −F (r,x

,y

,h(x

,y

)) ≡ G(r,x

,y

),

where the last line defines G. The triple integration has now been reduced to

adoubleintegral,andwehave

##

Ω

f(r, r

) dQ(r

)=

##

S

dx

dy

G(r,x

,y

).

We follow the same procedure as above to do the double integral. Once

again, the region of integration S mayhavetobedividedintoanumberof

other more easily integrable regions. However, let us assume that by inte-

grating the x

variable first, we will not need to divide the region. The x

integration is again a single integral and is done by keeping y

constant. To

find the upper limit of this integral, we pick an arbitrary point in S,fixits

second coordinate, and move “to the right” until we hit the boundary of S at

a point. The first coordinate of this boundary point, when expressed in terms

of y

, will be the upper limit of the x

integration. The lower limit is obtained

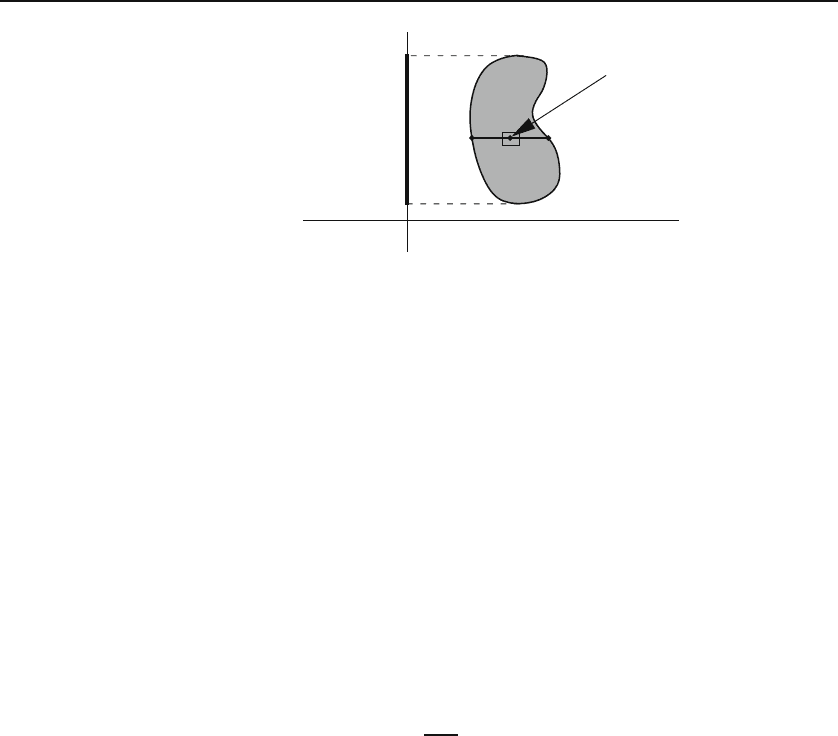

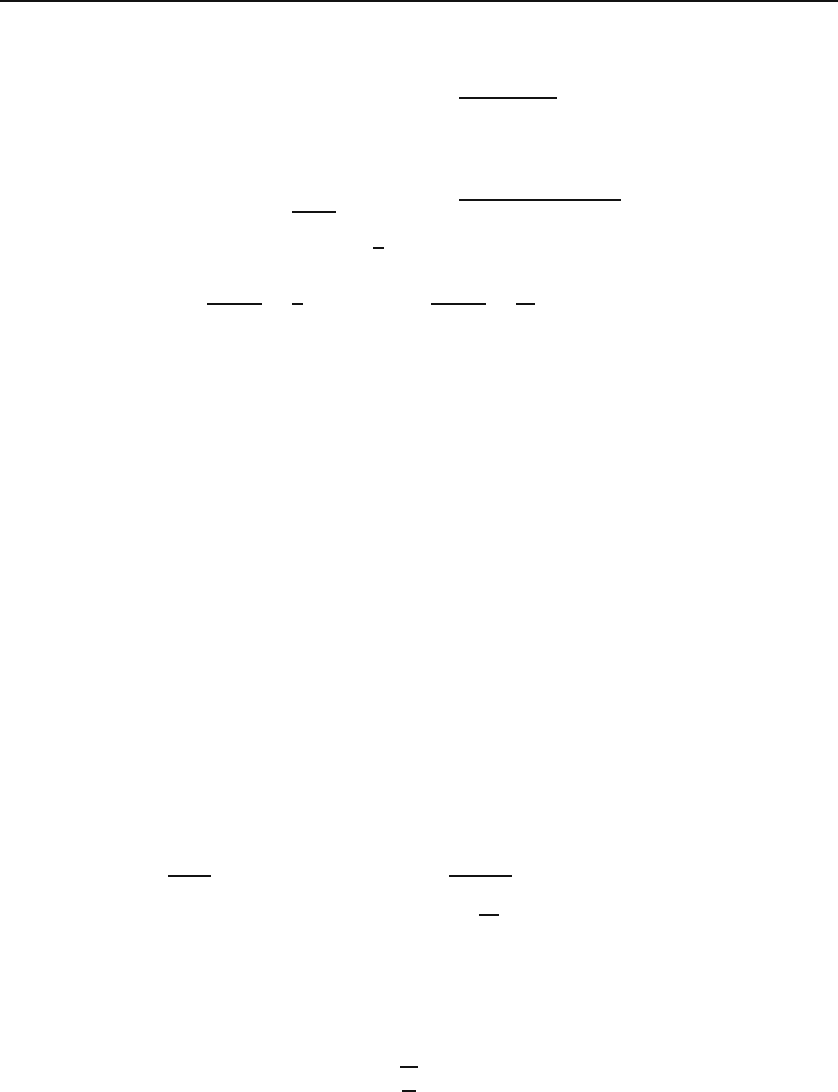

by “moving to the left.” Once again, in most cases, S is bounded by a given

upper curve of the form x = v(y), and a lower curve of the form x = u(y)(see

Figure 3.4). Thus, since the second coordinate of both boundary points is y

,

94 Integration: Formalism

x

y

v (

y

)

u ( y )

a

b

I

'

'

(x , y

)

'

'

Figure 3.4: The limits of the second integration of a triple integral are defined by two

curves.

the upper limit will be v(y

) and the lower limit will be u(y

). We thus write

the integral as

##

Ω

f(r, r

) dQ(r

)=

#

I

dy

#

v(y

)

u(y

)

dx

G(r,x

,y

),

where I is the projection of S on the y-axis. For I to be useful, it must have

thesamepropertyasS, namely: Every point of the right and left boundaries

of S has one and only one image in I, and no two points of the right (or left)

boundary project onto the same point in I. If this property is not fulfilled,

then we must choose y

as our first integration variable, or, if this does not

work, divide the region of integration into pieces for each one of which this

property holds. Assuming that I satisfies this property, and that the primitive

of the integrand, as a function of x

,isW (r,x

,y

), i.e, that

∂W

∂x

= G(r,x

,y

),

we get

#

v(y

)

u(y

)

G(r,x

,y

) dx

= W (r,v(y

),y

) −W (r,u(y

),y

) ≡ H(r,y

),

where the last line defines H. The triple integration has now been reduced to

a single integral, and we have

##

Ω

f(r, r

) dQ(r

)=

#

I

H(r,y

) dy

=

#

b

a

H(r,y

) dy

,

where a and b are the end points of the interval I.

Sometimes the inverse of the foregoing operation is useful whereby a single

integral is turned into a multiple integral. This happens when the integrand

is given in terms of an integral. To be specific, suppose in the integral

3.3 Guidelines for Calculating Integrals 95

I ≡

#

b

a

g(x) dx,

g(x)isgivenby

g(x)=

#

v

u

h(x, t) dt,

where u and v could be functions of x. Then, the original integral can be

written as

I =

#

b

a

(

#

v

u

h(x, t) dt

)

dx =

#

b

a

#

v

u

h(x, t) dt dx.

Example 3.3.1.

A historical example of this inverse operation is the evaluation

of the integral integral of e

−x

2

over the positive

real line

I ≡

#

∞

0

e

−x

2

dx.

As the reader attempting to solve this integral will soon find out, it is impossible to

find a primitive of the integrand. However, with

I

2

=

#

∞

0

e

−x

2

dx

=I

#

∞

0

e

−y

2

dy

=I

=

#

∞

0

#

∞

0

e

−x

2

e

−y

2

=e

−(x

2

+y

2

)

dx dy

weendupwithanintegrationoverthefirstquadrantofthexy-plane which opens up

the possibility of using other coordinate systems. In polar coordinates, the integrand

becomes e

−r

2

and the Cartesian element of area dx dy becomes the element of area

in polar coordinates, namely rdrdθ. The limits of integration correspond to the

first quadrant, with the range of θ being from 0 to π/2 and that of r being from 0

to infinity. This leads to

I

2

=

#

π/2

0

#

∞

0

e

−r

2

rdrdθ =

#

π/2

0

dθ

=π/2

#

∞

0

e

−r

2

rdr.

=−

1

2

e

−r

2

∞

0

This shows that I

2

= π/4 and, therefore, I =

√

π/2. The reader may verify that

#

∞

−∞

e

−x

2

dx =

√

π (3.26)

by either invoking the evenness of the integrand or starting from scratch as done

above.

3.3.2 Components of Integrals of Vector Functions

Many calculations involve an integrand which is a vector and whose integra-

tion also leads to a vector. Let us write this as

finding the

components of the

vector resulting

from integration

of another vector

F(r)=

##

Ω

A(r, r

) dQ(r

)

=

##

Ω

[A

1

(r, r

)

ˆ

e

1

(r

)+A

2

(r, r

)

ˆ

e

2

(r

)+A

3

(r, r

)

ˆ

e

3

(r

)] dQ(r

),

96 Integration: Formalism

where A

1

, A

2

,andA

3

are the components of the vector A along the mutually

perpendicular unit vectors

ˆ

e

1

,

ˆ

e

2

,and

ˆ

e

3

, respectively.

12

Note that these unit

vectors are, in general, functions of the variables of integration, and that

Box 3.3.1. The geometry of the distribution of the source determines the

most convenient variables of integration (coordinate variables).

To find the component of F(r) along any unit vector

ˆ

e

a

,onesimplytakes

the dot product of F(r)with

ˆ

e

a

.Thus,

F

a

(r) ≡

ˆ

e

a

· F(r)=

ˆ

e

a

·

##

Ω

A(r, r

) dQ(r

)=

##

Ω

[

ˆ

e

a

·A(r, r

)] dQ(r

)

≡

##

Ω

[A

1

(r, r

)f

1

(r

)+A

2

(r, r

)f

2

(r

)+A

3

(r, r

)f

3

(r

)] dQ(r

), (3.27)

where f

1

(r

) ≡

ˆ

e

a

·

ˆ

e

1

, f

2

(r

) ≡

ˆ

e

a

·

ˆ

e

2

,andf

3

(r

) ≡

ˆ

e

a

·

ˆ

e

3

. Once these dot

products are expressed in terms of the variables of integration, the integral

becomes an ordinary integral which, in principle, can be performed using the

guidelines above.

Box 3.3.2. In practice,

ˆ

e

a

is one of the unit vectors of some convenient

coordinate system which need not be the same as the coordinate system

used for integration.

For example, one may be interested in the Cartesian components of the grav-

itational field of a spherical distribution of mass. In that case, one uses spher-

ical coordinates for integration and the unit vectors inside the integral, and

ˆ

e

x

,

ˆ

e

y

,or

ˆ

e

z

for

ˆ

e

a

. We shall illustrate this point extensively with numerous

examples scattered throughout this chapter.

Historical Notes

By the time Newton entered the scene, an immense amount of knowledge of calculus

had accumulated. In his book Lectiones Geometricae, Barrow, for example, shows

a method of finding tangents, theorems on the differentiation of products and quo-

tients of functions, change of variables in a definite integral, and even differentiation

of implicit functions. So, why, one may wonder, is the word “calculus” so much

attached to Newton and Leibniz? The answer is in these two men’s recognition of

the generality of the methods of calculus, and, more importantly, their emphasis on

the newly discovered analytic geometry.

Isaac Newton was born in the hamlet of Woolsthorpe, England, two months

after his father’s death. His mother, in need of help for the management of the fam-

ily farm, wanted Isaac to pursue a farming career. However, Isaac’s uncle persuaded

him to enter Trinity College, Cambridge University. Newton took the entrance exam

12

These unit vectors are usually those of a convenient coordinate system.

3.3 Guidelines for Calculating Integrals 97

and was accepted to the College in 1661 with a deficiency in Euclidean geometry.

Apparently receiving very little stimulation from his teachers, except possibly Bar-

row, he studied Descartes’s G´eom´etrie,aswellastheworksofCopernicus, Kepler,

Galileo, Wallis,andBarrow, by himself.

Isaac Newton

1642–1727

Upon his graduation, Newton had to leave Cambridge due to the widespread

plague in the London area to spend the next eighteen months, during 1665 and

1666, in the quiet of his family farm at Woolsthorpe. These eighteen months were

the most productive of his (as well as any other scientist’s) life. In his own words:

In the beginning of 1665 I found the . . . rule for reducing any dignity

[power] of binomial to a series.

13

The same year, in May, I found the method

of tangents . . . and in November the direct method of Fluxions [the elements

of what is now called differential calculus], and the next year in January had

the theory of Colours, and in May following I had entrance into the inverse

method of Fluxions [integral calculus], and in the same year I began to think

of gravity extending to the orb of the Moon . . . and . . . compared the force

requisite to keep the Moon in her orb with the force of gravity at the surface

of the Earth.

Newton spent the rest of his scientific life developing and refining the ideas

conceived at his family farm. At the age of 26 he became the second Lucasian

professor of mathematics at Cambridge replacing Isaac Barrow who stepped aside

in favor of Newton. At 30 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, the highest

scientific honor in England.

Newton often worked until early morning, kept forgetting to eat his meals, and

when he appeared, once in a while, in the dining hall of the college, his shoes

were down at the heels, stockings untied, and his hair scarcely combed. Being

always absorbed in his thoughts, he was very naive and impractical concerning

daily routines. It is said that once he made a hole in the door of his house for his

cat to come in and out. When the cat had kittens, he added some smaller holes in

the door!

Newton did not have a pleasant personality, and was often involved in contro-

versy with his colleagues. He quarreled bitterly with Robert Hooke (founder of the

theory of elasticity and the discoverer of Hooke’s law) concerning his theory of color

as well as priority in the discovery of the universal law of gravitation. He was also

involved in another priority squabble with the German mathematician Gottfried Leib-

niz over the development of calculus. With Christian Huygens, the Dutch physicist,

he got into an argument over the theory of light. Astronomer John Flamsteed, who

was hardly on speaking terms with Newton, described him as “insidious, ambitious,

excessivelycovetous of praise, and impatient ofcontradictions...agood manatthe

bottom but, through his nature, suspicious.”

De Morgan says that “a morbid fear of opposition from others ruled his whole

life.” Because of this fear of criticism, Newton hesitated to publish his works.

When in 1672 he did publish his theory of light and his philosophy of science, he

was criticized by his contemporaries. Newton decided not to publish in the future,

a decision that had to be abandoned frequently.

His theory of gravity, although germinated in 1665 under the influence of works

by Hooke and Huygens, was not published until much later, partly because of his

fear of criticism. Another reason for this hesitance in publishing this result was his

13

Newton is talking about the binomial theorem here.

98 Integration: Formalism

lack of proof that the gravitational attraction of a solid sphere acts as if the sphere’s

map were concentrated at the center. So, when his friend Edmund Halley urged

him in 1684 to publish his results, he refused. However, in 1685 he showed that

a sphere whose density varies only with distance to the center does in fact attract

particles as though its mass were concentrated at the center, and agreed to write up

his work. Halley then assisted Newton editorially and paid for the publication. The

first edition of Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica appeared in 1687, and

the Newtonian age began.

3.4 Problems

3.1. Use Equation (3.7) to show that

a

a

f(t) dt =0.

3.2. In Equation (3.8), it was assumed that p<q<r. Show that the

equation holds even if q is not between p and r.

3.3. For each of the following integrals make the given change of variables:

(a)

8

0

tdt, t= y

3

. (b)

1

0

dt

1+t

2

,t=tany, 0 ≤ y ≤ π/2.

(c)

1

0

dt

1+t

,t=lny. (d)

∞

1

tdt

1+t

3

,t=

1

y

.

3.4. By a suitable change of variables, show the following integral identities:

(a)

∞

−∞

dt

(a

2

+t

2

)

3/2

=

2

a

2

π/2

0

cos tdt. (b)

∞

0

dt

(1+t)

2

=

1

0

dt.

3.5. If

g(x)=

#

sin(πx)

x

2

−1

{cos[π(t + x)]}e

−t

4

sin

2

[(π/2) ln(tx

2

+1)]

dt,

find g

(1).

3.6. Suppose that F (x)=

cos x

0

e

xt

2

dt, G(x)=

cos x

0

t

2

e

xt

2

dt,andH(x)=

G(x) − F

(x). Find H(x) in terms of elementary functions. Show that

H(π/4) = e

π/8

/

√

2.

3.7. Suppose that F (x)=

sin x

0

ln(cos

2

x + t

2

+1)dt, G(x)=

sin x

0

(cos

2

x +

t

2

+1)

−1

dt,andH(x)=F

(x)+2sinx cos xG(x). Find H(x)intermsof

elementary functions. Show that H(π/3) = ln 2/2.

3.8. Evaluate the derivative of the following integrals with respect to x at

the given values of x:

(a)

x

0

e

−t

2

dt at x =1. (b)

x

−3

cos tdt at x = π.

(c)

√

cos(x/3)

−∞

e

−t

2

dt at x = π. (d)

x

2

0

cos (

√

s) ds at x = π.

3.4 Problems 99

3.9. Find the numerical value of the derivative of the following two integrals

at x =1:

(a)

ln x

0

e

−x(t

2

−2)

dt. (b)

x

2

+a−1

a

sin

*

πxe

−t

2

2e

−(x

2

+a−1)

2

+

dt.

3.10. Write the derivatives with respect to x of the following integrals in

terms of other integrals. Do not try to evaluate the integrals.

(a)

b

a

ln(1 + sx) ds. (b)

b

a

dt

t

2

+x

2

. (c)

1

0

√

x

2

+ a

2

− 2ax cos tdt.

3.11. Differentiate

∞

−∞

dt/(z + t

2

)=π/

√

z with respect to z to show that

(a)

∞

−∞

dt

(1+t

2

)

2

=

π

2

. (b)

∞

−∞

dt

(1+t

2

)

3

=

3π

8

.

3.12. Using the method of Example 3.2.2, find the following integrals:

(a)

b

a

t

2

sin tdt. (b)

b

a

t

3

sin tdt. (c)

b

a

t

4

sin tdt.

(d)

b

a

t

2

cos tdt. (e)

b

a

t

3

cos tdt. (f)

b

a

t

4

cos tdt.

In each case calculate the primitive of the integrand and verify your answer

by differentiating the primitive.

3.13. Find the integral

Γ(n +1)=

#

∞

0

t

n

e

−t

dt

by first evaluating the integral

#

∞

0

e

−xt

dt

and then differentiating the result n times, and setting x = 1 at the end. Can

you see why Γ(n + 1) is called the factorial function?

3.14. Sketch each of the following integrands to decide whether the approxi-

mation to the integral is good or not.

(a)

0.1

−0.1

dt

10+t

2

≈ 0.02. (b)

0.1

−0.1

dt

0.001+t

2

≈ 200.

(c)

0.1

−0.1

cos(5πx) dx ≈ 0.2. (d)

0.1

−0.1

cos

πx

10

dx ≈ 0.2.

(e)

0.1

−0.1

e

−100t

2

dt ≈ 0.2. (f)

0.1

−0.1

e

−t

2

/100

dt ≈ 0.2.

3.15. Show that if a function is even (odd), then its derivative is odd (even).

3.16. Use the result of Example 3.3.1 to show that

#

∞

−∞

e

−xt

2

dt =

π

x

.

100 Integration: Formalism

3.17. By differentiating the electrostatic potential

Φ(r)=

##

Ω

k

e

dq(r

)

|r − r

|

with respect to x, y,andz, and assuming that Ω is independent of x, y,and

z, show that the electric field

E(r)=

##

Ω

k

e

dq(r

)

|r − r

|

3

(r − r

)

can be written as

E = −

∂Φ

∂x

ˆ

e

x

−

∂Φ

∂y

ˆ

e

y

−

∂Φ

∂z

ˆ

e

z

.

Chapter 4

Integration: Applications

The preceding chapter introduced integration and dealt with its formal as-

pects. It also gave some general guidelines concerning the calculation and

manipulation of integrals, in particular how to reduce the process of multiple

integration to a number of single integrations. In this chapter, we apply the

formalism of the previous chapter to concrete examples.

4.1 Single Integrals

This section is devoted to the simple but important case of single integrals

with examples from mechanics, electrostatics and gravity, and magnetostatics.

Generally, we encounter problems which are defined and set up in a single

dimension leading to integrals that have a single variable to be integrated.

4.1.1 An Example from Mechanics

In our discussion of primitive, Equation (3.18) clearly shows that integration

can be interpreted as the inverse of differentiation. Thus, if we know the

functional form of the derivative of a quantity, we should be able to express

the quantity in terms of an integral.

Velocity is the derivative of displacement. So, we seek to write displace-

ment in terms of an integral of velocity. This is easily done as follows:

1

dr

dt

= v(t) ⇒

dr

ds

= v(s) ⇒ dr = v(s) ds.

Integrating both sides from 0 to t,weget

#

t

0

dr =

#

t

0

v(s) ds ⇒ r(t) −r

0

=

#

t

0

v(s) ds, (4.1)

where r

0

= r(0), and we used Equation (3.21).

1

As cautioned below, we change t to s becauseweanticipateusingt as the upper limit

of the integral.