Gramley, Stephan; P?tzold, Kurt-Michael. A Survey of Modern English

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

share raincoat, but only BrE has mac(intosh); pharmacy is common, while chemist’s is

BrE only and drug store is typically AmE.

12.4.4 Relative frequencies and cultural associations

Many writers make absolute statements and do not take into account the evidence for

relative frequencies. Too little use has been made so far of such large scale corpora as

those assembled at Brown University for AmE (Francis and Kucˇera 1982) and at

Lancaster, Oslo and Bergen for BrE (Hofland and Johansson 1982). It is not the case, for

example, that railroad is found exclusively in AmE or railway only in BrE: ‘in the Brown

corpus railroad appears forty-seven times and railway ten; in LOB railway appears fifty-

two times and railroad once’ (Ilson 1990: 37).

Differences in cultural associations are almost wholly neglected. It is often pointed

out, for example, that robin refers to two different birds, but it is hardly ever mentioned

that the English bird is considered a symbol of winter while the American robin is a

harbinger of spring (Ilson 1990: 40). Scholars have, furthermore, also been prone to take

meaning in a narrow sense which excludes such use aspects as field, regional and social

distribution and differences in personal tenor (see 1.6.2). AmE vacation is holiday(s) in

BrE, as in they are on holiday/vacation now. But lawyers and universities in Britain use

vacation to refer to the intervals between terms. AmE pinkie, an informal word for little

finger, is an import from Scotland, where it is still the accepted word, as is borne out by

the regional labels ‘especially US and Scotland.’

Difficult and controversial, though of great importance in both the United States

and Great Britain, are the social class associations that items can have in the respective

variety. It is therefore not unimportant for Americans to know that in BrE lounge ‘is defi-

nitely non-U; drawing room definitely U’ [U = ‘upper class’] (Benson et al. 1986: 36).

Conversely, British people might be interested to hear about America that ‘Proles say tux,

middles tuxedo, but both are considered low by uppers, who say dinner jacket or (higher)

black tie’ (Fussell 1984: 152).

12.4.5 Lexis in the fields of university and of sports

Instead of listing further unconnected items we will now undertake a brief systematic

comparison of two fields, universities and the two ‘national’ sports of cricket and base-

ball. For the sake of convenience our discussion of university lexis will come under the

headings of people and activities.

University: people In higher education (common) or tertiary education (BrE) a

division may be made into two groups: the first are those who teach (the faculty, AmE;

the (academic) staff, BrE) and commonly include:

AmE (full) professors BrE professors

associate professors readers

assistant professors senior lecturers

instructors lecturers

292 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

And there are those who study:

AmE freshmen BrE first year students or freshers

sophomores second year students

juniors third year (also possibly: junior honours)

students

seniors final year (also possibly: senior honours)

students

Teaching and research is organized in departments (common) or faculties (BrE), and these

are under the administrative supervision of heads of department (common) or deans (BrE).

American colleges and universities also have deans, both deans of students, who are

responsible for counselling, and administrative deans at the head of a major division in

a college (which, in AmE, refers to undergraduate education) or a professional school

(AmE, postgraduate level, for example, in a school of medicine, law, forestry, nursing,

business administration etc.). At the top in the American system is a president. This is

not unknown in the UK: however, a chancellor (honorary) or vice chancellor (actual on-

the-spot chief officer) is more likely to be found there. On the other hand, a chancellor

in America is often the head of a state university system.

University activities Students in the United States go to a college and study a

major and a minor subject; in the UK they go up and then study, or read (formal), a main

and a subsidiary subject. While at college or university they may choose to live in a

dorm(itory) (AmE), a student hostel (BrE) or a hall (of residence) (BrE). If they mis-

behave, their may be suspended (AmE) or rusticated (BrE); in the worst of cases they

may even be expelled (AmE) or sent down (BrE). In their classes (common) they may

be assigned (AmE) a term paper (AmE) or given a (long) essay (BrE) to write. At the

end of a semester, trimester, quarter (all especially AmE) or term (common) they sit (BrE)

or take (common) exams which are supervised (AmE) or invigilated (BrE) by a proctor

(AmE) or invigilator (BrE). These exams are then corrected and graded (AmE) or marked

(BrE). The grades (marks) themselves differ in their scale: American colleges and univer-

sities mark from (high) A via B, C and D, to (low = fail) F, which are marks known and

used in the UK as well. In the US overall results for a term as well as for the whole of

one’s studies will be expressed as a grade point average with a high of 4.0 (all A’s). In

the UK a person’s studies may conclude with a brilliant starred first, an excellent first,

an upper second, a lower second or a third (a simple pass). Particularly good students

may wish to continue beyond the BA (common) or BS (AmE) or BSc (BrE) as a grad-

uate (especially AmE) or postgraduate (especially BrE) student. In that case they may

take further courses and write an MA thesis (AmE) or MA dissertation (BrE). Indeed,

they may even write a doctoral dissertation (AmE) or doctoral thesis (BrE).

Sports expressions Idioms, idiomatic expressions and figurative language from all

areas, but especially from the area of sports are used frequently in colloquial speech,

perhaps because they tend to be colourful. Many different types of sports are involved

(e.g. track and field, the university’s track record; boxing, saved by the bell; or horse-

racing, on the home stretch). Yet the two ‘national sports’, cricket and baseball, in

particular, have contributed especially to the language of everyday communication.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

STANDARD BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH IN COMPARISON 293

The following is a useful, but not an exhaustive list of the idioms which come from these

sports.

Since the two sports resemble each other (if ever so vaguely), they actually share some

expressions: batting order ‘the order in which people act or take their turn’; to field ‘enter

a competition as “to field candidates for an election”’; to take the field ‘to begin a

campaign’. The user should, however, beware of the seemingly similar, but in reality very

different expressions (BrE) to do something off one’s own bat ‘independently, without

consulting others’ vs (AmE) to do something off the bat ‘immediately, without waiting’.

Most of the expressions are, however, part of only cricket or only baseball. Of these

a couple from cricket are well integrated into both BrE and AmE without any longer

being necessarily closely identified with the sport: to stump ‘to baffle, put at a loss for

an answer’ (< put out a batsman by touching the stumps); to stonewall ‘to intentionally

draw out discussion and avoid giving an answer’ (< slow, careful overly protective play

by a batsman). Further expressions from cricket which are known, but not commonly

used in AmE are a sticky wicket ‘a difficult situation’ and (something is) not cricket ‘unfair

or unsportsmanlike’. Less familiar or totally unknown in AmE are to hit someone for

six ‘to score a resounding success’, to queer someone’s pitch ‘to spoil someone’s plans’,

to be caught out ‘to be trapped, found out, exposed’, a hat trick (also soccer) ‘three similar

successes in a row’, She has had a good innings ‘a long life’.

Baseball has provided the following collection of idiomatic expressions, most of which

have a very distinctly American flavour about them: to play (political, economic etc.)

hard ball ‘to be (ruthlessly) serious about something’, to touch base ‘to get in contact’,

not to get to first base with someone ‘to be unsuccessful with someone’, to pinch hit for

someone ‘to stand in for someone’, to ground out/fly out/foul out/strike out ‘to fail’, to

have a/one/two strikes against you ‘to be at a disadvantage’, to play in/to make the big

leagues ‘to work with/be with important, powerful people’, a double play ‘two successes

in one move’, take a rain check ‘postponement’, a grand slam (also tennis and bridge)

‘a smashing success or victory’, a blooper ‘a mistake or failure’, a doubleheader ‘a

combined event with lots to offer’, batting average ‘a person’s performance’, over the

fence or out of the ball park ‘a successful move or phenomenal feat’, out in left field

‘remote, out of touch, unrealistic’, off base ‘wrong’.

What have been illustrated here are only some examples of the many lexical and

idiomatic differences between the two varieties. This also seems to be the case in govern-

ment and politics, in cooking and baking, in clothing and in connection with many

technological developments up to the Second World War (railroads/railways, trucks/

lorries etc.). Nevertheless, as a matter of perspective, it is important to bear in mind that

the vocabulary and idioms associated with national institutions such as the educational

system and national sports will diverge more strongly than that of other areas. The vast

majority of vocabulary used in everyday, colloquial speech as well as that of international

communication in science and technology is common to not only AmE and BrE, but also

to all other national and regional varieties of English.

12.5 FURTHER READING

Fisher 2001 is a general historical treatment. Useful literature on pronunciation includes:

(for RP) Gimson 2001; (for GenAm) Bronstein 1960; and Wells 1982 (for both). Standard

294 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

pronouncing dictionaries for RP are Jones 1997; for GenAm, Kenyon and Knott 1944;

Wells 2000 gives both. Spelling: for more on internal variation within BrE, see

Greenbaum 1986; for AmE, see: Emery 1975; Venezky 1999. Information on punctua-

tion is found in a very concise form at the front or back of most modern dictionaries.

Most good dictionaries, whether AmE or BrE in their orientation, provide alternative

spellings, but they cannot always be counted on to include the standard spellings of the

other side of the Atlantic. See also 4.7.

Quirk et al. 1985 make frequent comments on BrE–AmE differences in grammar. Biber

et al. 1999 make highly illuminating corpus-based observations on such differences.

On sources of vocabulary including national differences in word formation and borrowing

see Gramley 2001. A typical comparative list is Moss 1994. Examples of loan words can

be found, for example, in McArthur 1996: 137ff. For collocations see Benson et al. 1997

(both AmE and BrE) and Oxford Collocations (2002) (BrE). Few writers and fewer word

lists or dictionaries give help with aspects of social class, but the books by Buckle (mainly

BrE; 1978); Cooper (BrE; 1981), Fussell (AmE; 1984; especially Chapter 7) provide some

orientation.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

STANDARD BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH IN COMPARISON 295

English in Australia, New Zealand

and South Africa

These three countries have been grouped together for a number of reasons. First of all,

they are the only large areas in the southern hemisphere in which English is spoken as a

native language. This itself is related to the relatively large-scale settlement of all three

by English speaking Europeans at roughly the same time (Australia from 1788, South

Africa essentially from 1820, New Zealand officially from 1840). All three were, for a

considerable period of time, British colonies and hence open to British institutions

(government, administration, courts, military, education and religion) as well as the use

of English as an official language. Other southern hemisphere places such as the Falkland

Islands, South Georgia, Fiji or Samoa will not be considered. East and West Africa are

included in Chapter 14 in section 14.1.2; Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea, in the section

on pidgins and creoles (14.3).

Each section of this chapter starts with a short sketch of settlement history, which

provides the background to the establishment of English as a local language. Mention is

also made of the number of speakers of English and other important languages as well

as official language policies and the status of English. Finally, there is a characterization

of English in these countries, taking into consideration pronunciation, grammar and vocab-

ulary as well as social, regional and ethnic variation.

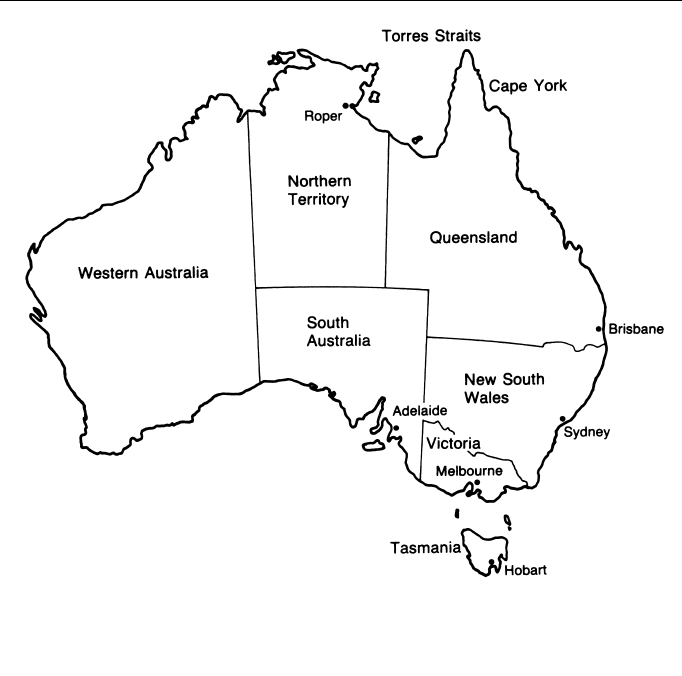

13.1 AUSTRALIAN ENGLISH (AusE)

When the first European settlers reached Port Jackson (present day Sydney) in New South

Wales in 1788 the continent was inhabited by the native or Aboriginal peoples. Since

these peoples were linguistically divided and technologically far less advanced than the

European newcomers, they had relatively little impact on further developments, including

language. Today the Aboriginal population numbers about 0.25 million in a total of about

19 million.

Initially Australia served as a British penal colony and was populated chiefly by trans-

ported convicts. With the economic development of the country (wool, minerals) the

number of voluntary immigrants increased, and it boomed after the discovery of gold in

1851. The convict settlers were chiefly Irish (30 per cent) and southern English. The latter

had the strongest influence on the nature of AusE. Because of their largely urban

origins the English they used contained relatively few rural, farming terms and perhaps

a greater number of words considered to be less refined in polished English society. The

Chapter 13

pronunciation which has developed, while distinctly Australian, has a clearly urban

southern English bias; and although it is often compared to Cockney, the similarities are

only partial (see below).

Today the vast majority of the population speaks English; and over 80 per cent of them

have it as their native language. Aboriginal languages are in wide use only in Western

Australia and the Northern Territory; in the late twentieth century Aboriginal languages

were used there by perhaps as much as a quarter of the population. Non-British immi-

gration has been significant since the Second World War. The long practised ‘white

Australia’ policy, which discouraged non-European, even non-British immigration

(except for New Zealanders) has yielded to more liberal policies: by the 1970s a third of

the immigrants were Asians and only a half were Europeans. Regardless of the presence

of numerous immigrant languages the primacy of English has never been called into

question; the influence of both immigrant and Aboriginal languages has been limited to

providing loan words.

13.1.1 AusE pronunciation

AusE is most easily recognized by its pronunciation. The intonation seems to operate

within a narrower range of pitch, and the tempo often strikes non-Australians as notice-

ably slow. Except for the generally slower pronunciations of rural speech, there is no

systematic regional variation in AusE, but there are significant social differences.

Frequently AusE pronunciation is classed in three categories. The first is referred to

as Cultivated and resembles RP relatively closely; it may, in fact, include speakers

whose pronunciation is ‘near-RP’. It is spoken by proportionately few people (in one

investigation of adolescent speakers approximately 11 per cent; see Delbridge 1970: 19);

nevertheless, it is the type of pronunciation given in the Macquarie Dictionary. The

second type is called General, spoken by the majority (55 per cent; Delbridge 1970);

its sound patterns are clearly Australian, but not so extreme as what is known as Broad

(34 per cent; Delbridge 1970), which realizes its vowels more slowly than General.

In the light of Australia’s early history, in which two groups stood in direct opposi-

tion to each other, namely the convicts and the officer class which supervised them, the

following remark seems fitting:

In sum, Australian English developed in the context of two dialects – each of them

bearing a certain amount of prestige. Cultivated Australian is, and continues to be,

the variety which carries overt prestige. It is the one associated with females, private

elite schools, gentility and an English heritage. Broad Australian carries covert pres-

tige and is associated with males, the uneducated, commonness and republicanism.

The new dialect is ‘General’ which retains the national identity associated with Broad

but which avoids the nonstandardisms in pronunciation, morphology and syntax asso-

ciated with uneducated speech wherever English is spoken.

(Horvath 1985: 40)

Today teenage speakers tend to cluster in the area of General, perhaps being pushed there

to distinguish themselves from the large number of immigrants who have adopted Broad

(ibid.: 175f.).

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND AND SOUTH AFRICA 297

AusE intonation In addition to the remark made above on the narrower range of pitch

in AusE, one further comment is appropriate. This is the use of what is called the high

rising tone (sometimes also called Australian Question Intonation), which involves the

use of rising contours (tone 2, see 4.5.3) for statements. It is part of the turn-taking mech-

anism, and it is used chiefly in narrative and descriptive texts. ‘And finally, at the heart

of it all is a basic interactive meaning of soliciting feedback from the audience, particu-

larly regarding comprehension of what the speaker is saying’ (Guy and Vonwiller 1989:

28). Like adding, ‘Do you understand?’ to a statement it requests the participation of the

listener (see CanE eh in 11.2.1). It is apparently a low prestige usage, favoured more by

young people; it is also more common among females than among males and may be

observed increasingly often, especially among young women, in other national varieties

of English.

AusE consonants There are only a few significant differences in the realization of

AusE consonants when compared with RP and also with GenAm. Among these is the

tendency to flap and voice intervocalic /t/ before an unstressed syllable in Broad and

General, though rarely in Cultivated. T-flapping is very similar to the same phenomenon

in GenAm. This necessarily means that there is an absence of the glottal stop [

ʔ], which

298 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Map 13.1 Australia

many urban varieties of BrE have in the same environment (e.g. butter is [bdə] =

‘budder’ rather than [b

ʔə] = ‘buh’er’.

Unlike GenAm, but like RP, AusE is non-rhotic. As in Cockney there is also a certain

amount of H-dropping (’ouse for house). However, Horvath’s Sydney investigation turned

up relatively little of this (ibid). In addition, the sound quality of /l/ is even darker than

a normal velarized [

]; it is, rather, pharyngealized [l

ɒ

] in all positions. Furthermore, there

seems to be widespread vocalization of /l/, which leads to a new set of diphthongs (see

examples under NZE, which is similar).

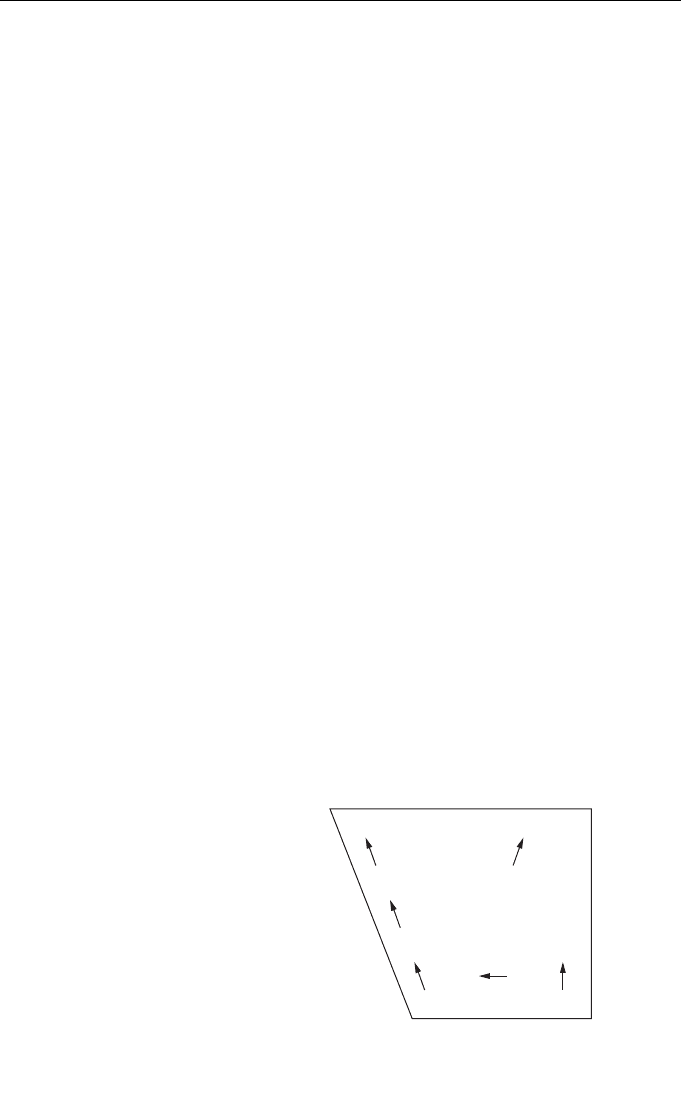

AusE vowels In the following the vowel system of General/Broad AusE is presented

schematically in comparison with an unshifted RP point of departure. One of the main

differences, noted by various observers, is a general raising of the simple vowels (see

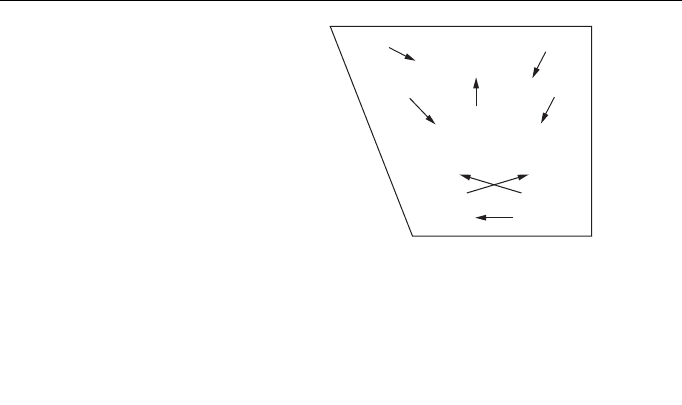

Figure 13.1). A counter-clockwise lowering and retraction of the first element in the diph-

thongs which move towards a high front second element, and a clockwise lowering and

fronting of the first element of the diphthongs which move towards a high back second

element are further changes (Figure 13.2).

To some extent AusE represents a continuation of the Great Vowel Shift, which began

in the late Middle English period and which is continuing in the same sense in London

English (Cockney) (see also 10.2.2, 10.4.1 and 11.2.2).

Beyond such differences in the phonetic realization of the vowels, it is notable that

far fewer unstressed vowels are realized as /

/ in AusE than in RP. This means that the

distinction maintained in RP between <-es> and <-ers> (as in boxes /

z/ and boxers /əz/

or humid /

d/ and humoured /əd/) is usually not made. Indeed, it may be possible to say

that there is a certain centralization of /

/ which brings it closer to /ə/, but also sometimes

to fronted [

%] as well. An Australia newsreader working for the BBC is supposed to have

caused some consternation by reporting that the Queen had chattered /

əd/ rather than

chatted /

d/ with workers. In addition, note that the final unstressed RP // pronunciation

of <-y> and <-i(e)> (hurry, Toni, hurries) is realized as /i

/.

The /

/–/a/ contrast in words of the type ask, after, example, dance etc. shows divided

usage in AusE, reminiscent of the same type of contrast between GenAm and RP. Apart

from the fact that vowel realization differs from word to word (i.e. does not affect this

class of words as a whole), one recent study shows significant regional distinctions. In

an identical set of words (e.g. castle, chance, contrast, demand, dance, graph, grasp)

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND AND SOUTH AFRICA 299

bit → b1t // → /2/

foot → foot /υ/ → /υ2/

bet → bit /ε/ → /ε2/

bat → bet // → /2/

cut → cut // → /

3/

box → box /ɒ/ → /ɒ2/

2υ2

υ

ε

ε2

2

ɒ2

3

Figure 13.1 The Southern Hemisphere Shift (Australia): the simple or short vowels

Adelaide lies closest to RP with a preponderance of /a/ (only 9 per cent //) while Hobart

is closest to GenAm with 72 per cent /

/. Furthermore, working class speech favours //

with the difference between working and middle class largest in Melbourne (33 percentage

points) and least in Brisbane (3 percentage points) (Bradley 1991: 228–31).

Among the vowels there is, finally, also a tendency to monophthongize the centring

diphthongs through loss of the second element. This levels the distinction, for example,

between /e

ə/ and /e/ (bared = bed). Together with the fronting and monophthongize of

/a

υ/ this can occasionally lead to misunderstandings such as the following one quoted in

Taylor between himself and a postal agent in the outback (1973/74: 59):

Author: Do you sell stamps?

Agent: Yes.

Author: I’d like airmail [= our mail for Australian ears], please.

Agent: Sorry, but your mail hasn’t come in yet.

Years of prescriptive schooling have not failed to have their effect on Australians, who

have only recently begun to gain a more positive attitude towards their own variety of

English (mostly pronunciation). Cultivated forms correlate ‘strongly with sex (nine girls

for every one boy), with superior education (especially in independent, fee-paying

schools), and comfortable urban living’ (Delbridge 1990: 72). Another linguist (Poynton)

is quoted as remarking that Cultivated was ‘good speech used by phony people whereas

Broad was bad speech used by real people’ (quoted in Horvath 1985: 24).

13.1.2 Grammar and morphology in AusE

There are no really significant differences in grammar between standard AusE and

standard BrE or AmE although formal usage in all areas seems to tend more towards BrE.

An investigation of the use of dare and need as modal or lexical verbs has shown, for

example, that there are some differences in preferred usage, but no absolute ones (Collins

300 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

fleas → fleas /i/ → /ə/

who → who /u/ → /əυ/

bird → bird // → /2/

face → fice /e/ → //

goat → goat /əυ/ → /υ/

out → at /ɑυ/ → /o/

I’ll → oil /a/ → /ɒ/ start → start /ɑ/ → /a/

i

ə 2

əυ

e

u

υ

əυ

o

ɑυ

ɒ

a

aɑ

Figure 13.2 The Southern Hemisphere Shift (Australia): long vowels and diphthongs

1978). Non-standard AusE usage is also very much like that of other countries in which

English is a widely spoken native language. If there are any differences in non-standard

AusE, they are in relative frequencies. For many AusE speakers, however, the use of the

plural verb in existential there constructions, even with singular subjects, is virtually cate-

gorical (Eisikovits 1991: 243f.). Sex differentiation seems, for example, to be stronger in

Australia than in the United States or Great Britain (especially in pronunciation, see Guy

1991: 222). A study of Inner Sydney usage reveals greater use of third person singular

don’t by males, probably ‘as a marker of group identity, “maleness” and working-class

values’ (Eisikovits 1991: 238f.).

In morphology AusE reveals a preference for several processes of word formation

which are less frequent in English at large. One of these is the relatively greater use of

reduplication, especially in designations for Australian flora and fauna borrowed from

Aboriginal languages (bandy-bandy, a kind of snake, gang-gang, a kind of cockatoo)

proper names (Banka Banka, Ki Ki, Kurri Kurri) and terms from Aboriginal life including

pidgin/creole terms (mia-mia ‘hut’, kai kai ‘food’). In addition the endings {-ee/-y/-ie}

/i

/ (broomy, Aussie, Tassie, Brizzie, surfy) and {-o} [υ] (bottlo, smoko) occur more often

in AusE than in other varieties.

13.1.3 AusE vocabulary

AusE shares all but a small portion of its vocabulary with StE; however this small,

Australian element is important for giving AusE its own distinctive flavour. Indeed, next

to pronunciation it is the distinctively Australian words which give this variety its special

character. Rhyming slang, though hardly of frequent use, is often regarded as especially

typical of AusE, e.g. sceptic tanks ‘Yanks’. In addition, there are a number of Australian

words which originate in English dialects and therefore are not a part of StE everywhere,

e.g. bonzer ‘terrific’, chook(ie) ‘chicken’, cobber ‘mate’, crook ‘ill’, dinkum ‘genuine’,

larrikin ‘rowdy’, swag ‘bundle’, tucker ‘food’ (for much of the material in the following,

see Turner 1994).

The specific features of AusE vocabulary have been affected most strongly, however,

by borrowing (kangaroo) and compounding (kangaroo rat; black swan; native dog,

lyrebird (bird), ironbark (tree), outback ‘remote bush’, or throwing stick ‘woomera,

boomerang’). Place names, of course, are often specifically Australian (Wallaroo,

Kwinana, Wollongong, Wagga Wagga), including fantasy names such as Bullamakanka

(fictitious place); Woop Woop (fictitious remote outback locality), both with Aboriginal-

sounding names. Sometimes there is uncertainty even among Australians about how to

pronounce them. So the anecdote about the train approaching Eurelia, where one porter

goes through the cars announcing /ju

rəlaə/ (‘You’re a liar’) and is followed by a second

yelling /ju

rilia/ (‘You really are’) (Turner 1972: 198). Regionally differing vocabulary

is rare, but includes words for a bathing suit: togs, cossie, swimmers (East Coast, NZ:

togs), bathers (South + Western Australia). Language Varieties Network at http://www.

une.edu.au/langnet/ concentrates more on minority and stigmatized varieties, including

pidgins and creoles from a sociolinguistic viewpoint.

There are, of course, words Australian by origin but accepted throughout the English

speaking world because what they designate is some aspect of reality which is distinc-

tively Australian. Chief among these are words for the flora, fauna and topography of

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND AND SOUTH AFRICA 301