Gramley, Stephan; P?tzold, Kurt-Michael. A Survey of Modern English

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

13.3.4 Coloured SAE

The Coloured population has traditionally spoken Afrikaans. However, among the

speakers of Coloured SAE the characteristics of this type of English are similar to (low

prestige) Extreme SAE/Cape English. Yet its speakers seem to cultivate it as a symbol

of group identity and solidarity.

13.3.5 Indian SAE

This variety of SAE is spoken by approximately three quarters of a million South Africans

of Indian extraction; most of them live in largely English speaking Natal. It is predicted

that English will eventually replace those Indian languages which still are spoken not

only in education and economic life, but also as the home language.

Linguistically Indian SAE, especially that of older speakers, has a number of charac-

teristics of IndE (see 14.2.1), such as the merger of /w/ and /v/, the use of retroflex alveolar

consonants, and [e

] and [o] for /e/ and /əυ/. Yet Conservative SAE appears to be the

overt standard of pronunciation and younger speakers seem to be shifting towards it.

Many basilect speakers of South African Indian English employ non-standard construc-

tions to form relative clauses, using, for example, personal pronouns instead of relative

ones (e.g. You get carpenters, they talk to you so sweet) or allowing the relative to

precede the clause containing the noun it refers to (e.g. Which one haven’ got lid, I threw

them away ‘I threw the bottles that don’t have caps away’) (Mesthrie 1991: 464–7).

Furthermore, in basilect speech that faller, pronounced daffale in rapid delivery, is used

as a personal pronoun. It is also reported that the area of topicalization (for example, the

fronting of elements in a sentence to make them thematic) and the use and non-use of

the third person present tense singular and the noun plural ending {-

S

} vary socially within

the group of South African Indian English speakers. Despite the constructions and usages

just mentioned, younger and better educated South Africans of Indian ancestry, who are

usually native speakers of English, share most features of their English with other mother

tongue speakers of SAE.

13.4 FURTHER READING

AusE Burridge and Mulder 1998 describe both AusE and NZE. Turner 1994 looks at

AusE in general. For AusE regional differences in pronunciation, see Bradley 1989; for

details on sociolinguistic distinctions, see Horvath 1985. Arthur 1997 deals with

Aboriginal English.

AusE vocabulary. Baker’s pioneering book, The Australian Language 1966, devotes

most of its space to Australian words. This includes both slang and more formal usage;

see also: Delbridge 1990; Turner 1972; 1994; Gramley 2001; and A Dictionary of Aus-

tralian Colloquialisms. The Macquarie Dictionary, the Heinemann New Zealand Diction-

ary and the Australian National Dictionary all cater to both Australia and New Zealand;

The Australian Concise Oxford Dictionary includes only AusE and not NZE. For a report

on regional variation in AusE vocabulary, see Bryant 1985. Taylor 1989 provides a

312 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

number of further items borrowed from AmE to which he adds comments on spelling,

morphology and syntax. The Language Varieties Network at http://www.une.edu.au/

langnet/ concentrates more on minority and stigmatized varieties, including pidgins and

creoles from a sociolinguistic viewpoint.

NZE Bell and Holmes 1990 give a general treatment of NZE; see also Bauer 1994;

Holmes, Bell and Boyce 1991. For vocabulary, see Heinemann New Zealand Dictionary

or The New Zealand Pocket Oxford Dictionary (and references under AusE above).

SAE SAE in general is described in W. Branford (1994). South African language

policy is treated very succinctly in Methrie et al. 2000. SAE pronunciation: Lanham

and Macdonald 1979: 46f.; Lanham 1984: 339; Wells 1982. SAE vocabulary: Branford

1991 is an excellent source for SAE lexical items; see also Beeton and Dorner 1975.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND AND SOUTH AFRICA 313

English as a second language

(ESL)

The previous chapters in Part 3 have looked at those countries in which English is spoken

as a native language, if not by the total population, at least by a significantly large group.

This chapter continues the geographic survey of English by observing its use as a second

language in Africa (14.1) and in Asia (14.2) and the use of English pidgins and creoles

in 14.3.

The idea of second language is only slightly different from that of foreign language,

for it is less the quality of a speaker’s command than the status of the language within a

given community that determines whether it is a second or a foreign language. In an

unambiguous case, a foreign language is a language learned in school and employed for

communicating with people from another country. A second language, in contrast, may

well be one learned in school, too, but one used within the learner’s country for official

purposes and reinforced by the power of the state and its institutions.

As far as English is concerned, second language status is quite common. Not only are

bilingual French-English Canada (Chapter 11), Irish-English Ireland (Chapter 10) and

South Africa (Chapter 13) cases where English is, for some people, a second language;

in addition, English is a second language in numerous countries in Asia and Africa, where

it is the official or semi-official language, a status sometimes shared with one or more

other languages. In these states English is typically not the native language of more than

a handful of people. There are some 35 such countries, 26 in which English is an official

language and 9 further ones in which it is so in reality. The first group includes Botswana,

Cameroon (with French), Fiji, Gambia, Ghana, Hong Kong, India (with Hindi), Lesotho

(with Sesotho), Liberia, Malawi (with chi-Chewa), Malta (with Maltese), Mauritius,

Namibia (with Afrikaans and German), Nauru (with Nauru), Nigeria (with Igbo, Hausa

and Yoruba), the Philippines (with Filipino/Pilipino/Tagalog), Sierra Leone, Singapore

(with Chinese, Malay and Tamil), Swaziland (with Siswatsi), Tanzania (with Swahili),

Tonga (with Tongan), Uganda, Vanuatu (with Bislama and French), West Samoa (with

Samoan), Zambia and Zimbabwe. The second group consists of Bangladesh, Burma,

Ethiopia, Kenya, Pakistan, Malaysia, Israel, Sri Lanka and Sudan.

The number of second language users of English is estimated at about 300 million

(but see Crystal 1997: 61, who opts for 1 billion), i.e. roughly the same number as that

of English native speakers. Whatever the exact figure may be, English is the present day

language of international communication.

The circumstances that have led to the establishment of English, an outside language,

as a second language in so many countries of Africa and Asia are not education and

Chapter 14

commerce alone, however important English is for these activities and however strong

the economic hegemony of the English speaking world is. Quite clearly it is the legacy

of colonialism that has made English so indispensable in these countries, of which only

Ethiopia was never a British or American colony or protectorate. (Where the colonial

master was France, Belgium, or Portugal, French and Portuguese are the second

languages.) The retention of the colonial language is a conscious decision and may be

assumed to be the result of deliberate language policy and language planning. Among the

factors which support the use of English as an official language are the following:

• the lack of a single indigenous language that is widely accepted by the respective

populations; here English is neutral vis-à-vis mutually competing native languages

and hence helps to promote national unity;

• the usefulness of English in science and technology as opposed to the underdevel-

oped vocabularies of the vernaculars;

• the availability of school books in English;

• the status and use of English for international communication, trade and diplomacy.

In these countries English plays an important role in government and administration,

in the courts, in education (especially secondary and higher education), in the media and

for both domestic and foreign economic activity. English is, in other words, an extremely

utilitarian, public language. It is also used, in a few cases, as a means of expressing

national unity and identity versus ethnic parochialism (see especially Singapore). As a

result second language English users are in the dilemma of diglossia: they recognize the

usefulness of English, yet feel strong emotional ties to the local languages. English is the

diglossically High language, used as official, public language vis-à-vis the indigenous

languages, which are more likely to be diglossically Low, and therefore to be preferred

in private dealings and for intimacy and emotion. Family life is typically conducted in

the ethnic or ancestral vernaculars. Where the High language is the standard and the Low

one is the variety of same language which is most divergent from it and where there are

also a number of varieties along a continuum between the two, it is common to refer to

the High language as the acrolect, the Low one as the basilect and the intermediate ones

as mesolects.

English, in other words, is far from displacing the vernaculars. Historically, the condi-

tions for language replacement have been, as the cases of Latin and Arabic show: (1)

military conquest; (2) a long period of language imposition; (3) a polyglot subject group;

and (4) material benefits in the adoption of the language of the conquerors (see Brosnahan

1963: 15–17). In modern Africa and Asia additional factors such as: (5) urbanization; (6)

industrialization/economic development; (7) educational development; (8) religious orien-

tation; and (9) political affiliation (Fishman et al. 1977: 77–82) are also of importance.

Yet the period of true language imposition has generally been relatively short and

economic development at the local level has been less directly connected with the colonial

language, so that English has tended to remain an urban and elite High language.

All the same, where English is widely used as a second language there is often as

much local pride in it on the part of the educated elite as there is resentment at its intru-

sion. As a result there has been widespread talk of the recognition of a ‘local’ standard,

especially in pronunciation, either a regional one such as Standard West African English

or a national one such as Standard Nigerian English. Some have emphasized the negative

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 315

aspects of such ‘nativization’ or ‘indigenization’, which may sometimes lower inter-

national intelligibility, and, more importantly, preclude the development of the indigenous

languages. A neglect of the vernaculars includes the danger of producing large numbers

of linguistically and culturally displaced persons. On the other hand, the spread of English

may be accompanied, for most of its users, by relatively little emotional colouring –

whether positive or negative. Indeed, some would go so far as to maintain: ‘The use of

a standard or informal variety of Singaporean, Nigerian, or Filipino English is . . . a part

of what it means to be a Singaporean, a Nigerian, or a Filipino’ (Richards 1982: 235).

As the following sections show, there is indeed room for a wide diversity of opinions on

this subject, and the developments in one country may be completely different in tendency

from those in another.

14.1 ENGLISH IN AFRICA

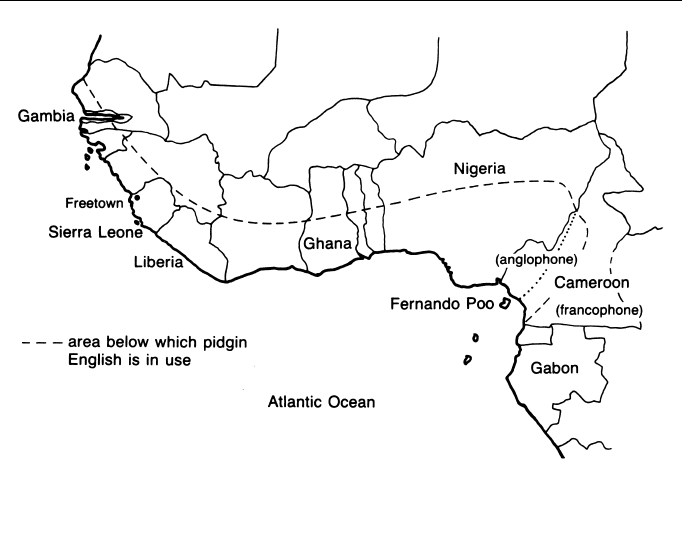

Second language English in Africa may be divided into three general geographic areas:

the six anglophone countries of West Africa (Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria

and Sierra Leone plus Fernando Poo, where Creole English is spoken), those of East

Africa (Ethiopia, Somalia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi and Zambia) and those of

Southern Africa (Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Lesotho and South Africa;

see 13.3 on South Africa). English is an official language for millions of Africans in these

countries, but the number of native speakers probably lies overall at around one per cent

of the population of these countries.

The first group includes two countries which have native speakers of English (Liberia,

five per cent) or an English creole (Sierra Leone, also five per cent) (percentages according

to Brann 1988: 1421). All six are characterized by the presence and vitality of Pidgin

English, used by large numbers of people. Neither Eastern nor Southern Africa has pidgin

or creole forms of English. However, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Namibia all have a

fairly large number of non-black native speakers of English (South Africa: approximately

40 per cent of the non-black population; Namibia, 8 per cent; Zimbabwe, virtually all the

white population).

English in Africa, though chiefly a second language and rarely a native language of

African Blacks is, nevertheless, sometimes a first language in the sense of familiarity and

daily use. Certainly, there are enough fluent, educated speakers of what has been called

African Vernacular English who ‘have grown up hearing and using English daily, and

who speak it as well as, or maybe even better than, their ancestral language’ for it to

serve as a model (Angogo and Hancock 1980: 72). Furthermore, the number of English

users is also likely to increase considering the number of Africans who are learning it at

schools throughout the continent, especially secondary schools.

Despite numerous variations, due in particular to the numerous mother tongues of its

speakers, this African Vernacular English is audibly recognizable as a type and is distinct

from, for instance, Asian English. It tends to have a simplified vowel system in relation

to native speaker English. Furthermore, it shares certain grammatical, lexical, semantic

and pragmatic features throughout the continent. These include different prepositional,

article and pronoun usage, comparatives without more, pluralization of non-count nouns,

use of verbal aspect different from StE, generalized question tags, a functionally different

application of yes and no, semantic shift as well as the coinage of new lexical items.

316 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Various expressions, such as the interjection Sorry!, are employed in a pragmatic sense

unfamiliar to StE. For more details see the following.

14.1.1 West Africa

The six anglophone countries, Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra

Leone (see Map 14.1) are polyglot. Nigeria has up to 415 languages; Cameroon, 234;

Ghana, 60; and even Liberia, Sierra Leone and Gambia have 31, 20 and 13 respectively

(Brann 1988: 1418f.). In this situation it is obvious that any government has to be

concerned about having an adequate language for education and as a means of general

internal communication. Where there is no widely recognized indigenous language to do

this, the choice has usually fallen on the colonial language. In Cameroon both colonial

languages, French (80 per cent of the country) and English (the remainder) were adopted

when the two Cameroons were united. A bilingual French-English educational policy is

pursued. Of the six states just mentioned only Nigeria has viable native lingua francas

which are readily available for written use, most clearly Hausa in the north, but also

the regional languages Yoruba in the west and Igbo in the east; all three are being devel-

oped as official languages. However, in Nigeria as a whole, as well as the other five, it

is English which fulfils many or most of the developmental and educational functions.

It is possible to speak of triglossia in these countries: at the lowest level, the autochthon-

ous languages; at an intermediate level, the regional languages of wider communication;

and superimposed on the whole, the outside or exogenous language, English (Brann 1988:

1416). For the most part the vernaculars and English are not in conflict, but are comple-

mentary, with English reserved for the functions of a High language in the sense of

diglossia while the local languages are the Low languages. Note, however, speakers who

do not share a native language prefer to communicate in a regional one. If that is not

feasible, they will choose Pidgin English. English itself is likely to be the last choice in

diglossically Low communication.

English in West Africa English is present in West Africa in a continuum of types

which runs from British StE with a (near-) RP accent (in Liberia the orientation is towards

AmE), to a local educated second language variety, to a local vernacular, to West African

Pidgin or one of its creolized varieties. This diversity of levels is one of the results of the

history of European-African contact on the west coast of Africa.

Pidgins and creoles Europeans went to the Atlantic coast of Africa in the first phase

of European colonialism from 1450 on. Initial trade contacts gradually expanded as a part

of the West Indian–American plantation and slave system, in which West Africa’s role

was chiefly that of a supplier of slaves. Throughout the era of the slave trade (Britain and

the US outlawed it in 1808; other European countries slowly followed), Europeans and

Africans conducted business by means of contact languages called pidgins (see 14.3).

Pidgin English continues to be used today all along the West African coast from Gambia

to Gabon though it is not always immediately intelligible from variety to variety. It is a

diglossically Low language like most of the indigenous vernaculars and is, for example,

said to be the most widely used language in Cameroon. It is perhaps so easily learned

not only because it is simplified, but also because it is structurally so close to the

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 317

indigenous languages. Its spread and importance in Cameroon is influenced by its use on

plantations and other work sites, in churches, markets, playgrounds and pubs. It is the

regular language of the military and the police and is also commonly used in the law

courts.

Standard English StE was introduced in the second major phase of colonialism in

the nineteenth century, when the European powers divided up as much of Africa and Asia

as they could. As a part of this movement there was a wave of Christian missionary effort

in Africa: ‘English was to become the language of salvation, civilisation and worldly

success’ (Spencer 1971b: 13). Although the church made wide use of the native languages

and alphabetized various of them for the first time, it had little use for Pidgin English.

The result was the suppression of Pidgin and Creole English by school, church and

colonial administration in favour of ‘“correct” bourgeois English’ (ibid.: 23). StE was

and is used in education, in government, in international trade, for access to scientific and

technical knowledge and in the media. It is a status symbol, a mark of education and

westernization. While StE thus functions as the badge of the local elite, Pidgin English

has little prestige, but does signal a good deal of group solidarity. Linguistically speaking,

Pidgin and Creole English are often regarded as independent languages and hence outside

the continuum of English; for ‘throughout West Africa, speakers are usually able to say

at any time whether they are speaking the one or the other’ (Angogo and Hancock 1980:

72). Nevertheless, many people as well as the governments generally view pidgin and

creole as English, albeit of an ‘uneducated’ variety. For speakers who have a limited

command of the stylistic variations of native speaker English, Pidgin English may function

as an informal register.

318 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Map 14.1 West Africa

Whatever perspective is taken, it is a fact that only a local, educated variety may be

regarded as a serious contender for the label West African StE. Such a form of English,

which implies completed primary or secondary education, is available to perhaps ten per

cent of the population of anglophone West Africa. A study of prepositional use in Nigerian

English provides support for the view that an independent norm is growing up which

contains not only evidence of mother tongue interference, but also of what are termed

‘stable Nigerianisms’. (In addition, this study shows that a meaningful sociolinguistic

division of Nigerian English is one which, reflecting the educational structure of the

country, distinguishes the masses, the sub-elite and the elite (Jabril 1991: 536). Some of

the characteristics of Nigerian English will be enumerated in the following section.

Linguistic features of educated West African English (WAfrE) Within

WAfrE there is a great deal of variation; indeed, the higher the education of a user, the

closer his or her usage is likely to be to StE. In this sense standard WAfrE is perhaps

less a fixed standard than a more or less well learned second language. At the upper end

of the continuum of Englishes in West Africa there are few or no syntactic or semantic

differences from native speaker English and few if any phonological differences from RP

or GenAm. Although this variety is internationally intelligible, it is not widely accept-

able for native Africans in local West African society. This is substantiated to some extent

by the fact that a good deal of the difference between the StE of native speakers and that

of educated West Africans can be explained by interference from the first language of

the latter. All of this notwithstanding, there are features of educated WAfrE which form

a standard in the senses that: (a) they are widely used and no longer amenable to change

via further learning; and (b) they are community norms, not recognized as ‘errors’ even

by relatively highly trained anglophone West Africans.

The pronunciation of WAfrE Most noticeable to a non-African, as with all the types

of StE reviewed in this book, is the pronunciation. Generally speaking, West Africans

have the three diphthongs /a

, aυ, ɔ/ and a reduced vowel system as represented in

Table 14.1. What is noticeable about the list is the lack of central vowels. This means

that schwa /

ə/ is also relatively rare, which fits in with the tendency of WAfrE to give

each syllable relatively equal stress (syllable-timed rhythm). In addition, the intonation is

less varied. Important grammatical distinctions made by intonation, such as the differ-

ence between rising and falling tag questions, may be lost. Emphasis may be achieved

lexically, by switching from a short to a long word, for instance from ask to command

to show impatience (Egbe 1979: 98–101). In the same way cleft sentences are likely to

be more frequent in the spoken language of Nigerian speakers than of non-African native

speakers (Adetugbo 1979: 142). The consonant system is the same as in RP, but there is

a strong tendency towards spelling pronunciations of combinations such as <-mb> and

<-ng>; this also means that although WAfrE is non-rhotic, less educated speakers may

pronounce /r/ where it is indicated in the spelling. There are, of course, numerous regional

variations such as that of Hausa speakers, who tend to avoid consonant clusters, so

that small becomes /s

u

mɔl/ (Todd 1984: 288). Among other things, for some speakers

/

θ/ becomes /t/.

The grammar of WAfrE The syntactic features of standard WAfrE are difficult to

define. A study of deviation from StE in Ghanaian newspapers reveals numerous syntactic

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 319

problems, but very few general patterns (Tingley 1981). Among the points that are

frequently mentioned and which therefore presumably have a fair degree of currency are

the following:

1 the use of non-count nouns as count nouns (luggages, vocabularies, a furniture, an

applause);

2 pleonastic subjects (The politicians they don’t listen);

3 an overextension of aspect (I am having a cold);

4 the present perfect with a past adverbial (It has been established hundreds of years

ago);

5 comparatives without more (He values his car than his wife);

6 a generalized question tag (It doesn’t matter, isn’t it?);

7 a functionally different use of yes and no (Isn’t he home? Yes [he isn’t]).

Most of these points (except 5) show up in Asian English as well, which suggests that

their source may well lie in the intrinsic difficulty of such phenomena in English. Indeed,

(6) may show up in BrE as in the following example:

‘Yeah, well, we don’t need strength,’ said Millat tapping his temple, ‘we need a little

of the stuff upstairs. We’ve got to get in the place discreetly first, innit? . . .’

(Zadie Smith (2001) White Teeth, London:

Penguin, p. 474)

The vocabulary of WAfrE The English vocabulary of West Africa has special words

for local flora, fauna and topography. In addition, special elements of West African culture

and institutions have insured the adoption of numerous further items. This, more than

grammar, gives WAfrE its distinctive flavour, reflecting as it does the sociolinguistic

context of WAfrE. The words themselves may be:

• English words with an extension of meaning, e.g. chap ‘any person, man or woman’;

• semantic shifts: smallboy ‘low servant’; cane ‘bamboo’;

320 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Table 14.1 The vowels of WAfrE in comparison with those of RP

WAfrE RP as in WAfrE RP as in

ii

bead ɔbird

bid bud

ee

bayed ɒ body

ε e bed ɔ bawdy

a

bad o əυ bode

ɑ bard u υ Buddha

u booed

Source: Adapted from Angogo and Hancock 1980: 75.

• new coinages using processes of affixation, compounding or reduplication: co-wives

‘wives of the same husband’; rentage ‘(house) rent’; bush-meat ‘game’; slow slow

‘slowly’;

• new compounds: check rice ‘rice prepared with krain-krain’; head tie ‘woman’s head-

dress’;

• words now outdated in Britain/America: deliver ‘have a baby’; station ‘town or city

in which a person works’;

• calques/loan translations, next tomorrow ‘day after tomorrow’ from Yoruba otunla

‘new tomorrow’;

• borrowings from a native language: awujor ‘ceremony giving the ancestors food’;

krain-krain ‘a leafy vegetable’;

• borrowings from pidgin/creole: tai fes ‘frown’; chop ‘food’;

• borrowings from other languages: palaver (Portuguese) ‘argument, trouble’; piccin

(Portuguese) ‘child’.

Most of these are restricted in use to West Africa, but some may be known and used

more widely, e.g. calabash, kola or palm wine.

Some pragmatic characteristics of WAfrE The cultural background of West

African society often leads to ways of expression which are unfamiliar if not misleading

for outsiders. This is surely one of the most noticeable ways in which second language

English becomes ‘indigenized’. A frequently quoted example is the use of Sorry! as an

all-purpose expression of sympathy, that is, not only to apologize for, say, stepping on

someone’s toes, but also to someone who has sneezed or stumbled. Likewise, Wonderful!

is used to reply to any surprise (even if not pleasant), and Well done! may be heard as a

greeting to a person at work.

The difference in family structure between the Western world and West Africa means

that kinship terms (father, mother, brother, sister, uncle, aunt etc.) may be used as in the

West, but, because polygyny is practised in West African society, family terms may also

be extended to the father and all his wives and all their children, or even to the father

and all his sons and their wives, sons and unmarried daughters. The terms father and

mother are sometimes also applied to distant relatives or even unrelated people who are

of the appropriate age and to whom respect is due. When far away from home, kinship

terms may be applied to someone from the same town or ethnic group, or, if abroad, even

to compatriots (see also 8.3). One further example of such culturally constrained language

behaviour concerns greetings, where different norms of linguistic politeness apply: ‘the

terms Hi, Hello, and How are you can be used by older or senior persons to younger or

junior ones, but not vice-versa. Such verbal behavior coming from a younger person would

be regarded as off-hand’ (Akere 1982: 92).

14.1.2 East Africa

The main countries of East Africa to be reviewed are Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda (see

Map 14.2). All three share one important feature: the presence of Swahili as a widely

used lingua franca. Structurally speaking, this language is therefore somewhat parallel

within East African society to Pidgin English in West Africa. However, while Pidgin

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 321