Gramley, Stephan; P?tzold, Kurt-Michael. A Survey of Modern English

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

common to the Caribbean creoles. Likewise, past perfective or completive done (already

mentioned) is found in these creoles.

The verb does not have to be marked for tense, although the particle been (or did or

had) + verb is available for marking the past and go or gain + verb are used for the future.

However, aspect is always expressed, whether process (e.g. da or duz + verb, sometimes

with the ending -in), completive or perfective (e.g., dun + verb), or active of a dynamic

verb or stative of a state verb (zero marking). These particles can also be combined in

various more complex structures. These examples of verb usage are taken from Bajan,

the Barbados basilect (Roy 1986). In addition, the creoles make use of serial verbs, such

as come or go, indicating movement towards or away from the speaker (carry it come

‘bring it’) or instrumental tek (tek whip beat di children dem ‘beat them with a whip’)

(Roberts 1988: 65). The passive is widely expressed by the intransitive use of a transi-

tive verb (The sugar use already ‘was used’), but there is also a syntactic passive with

the auxiliary get (The child get bite up) as well as the possibility of impersonal expres-

sions (Dem kill she ‘She was killed’) (ibid.: 74f.).

All of these points make clear the close relationship within this ‘family’ of creoles.

These correspondences have sometimes been strengthened and sometimes weakened by

the one factor or the other such as population movement in the Caribbean (see 11.5). The

single most important factor affecting almost all of these English creoles is the presence

of Standard Caribbean English as the acrolect.

West Africa The linguistic situation in West Africa is significantly different inasmuch

as there is no large native English speaking population in this region. English is, it is true,

the official language of Cameroon (with French), Gambia, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria

and Sierra Leone, but it is almost exclusively a second language. One of the chief results

of this is that there is no continuum like that found in the Caribbean. Instead, English is

the diglossically High language (as are such regional languages as Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa

in Nigeria), and West African Pidgin English (WAPE) is diglossically Low (as are

the numerous local indigenous languages). There are intermediate varieties of English

and, therefore, a continuum of sorts. However, these forms are not like the mesolects of

the Caribbean, but are forms of second language English noticeably influenced by the

native languages of their various speakers. Note that in West Africa there are relatively

few creole speakers and relatively many pidgin users. West African Standard English is

in wide use by the more highly educated in the appropriate situations (administration,

education, some of the media). WAPE is employed as a lingua franca in inter-ethnic

communication in multilingual communities, sometimes for relaxed talk or joking and as

a market language, even in the non-anglophone countries of West Africa.

However, because the pidgin has such a great amount of internal variation, some people

feel that there is a need for some type of standardization of it. Sometimes the pidgin is

a marginal pidgin or jargon, which is more severely limited in use, vocabulary and

syntax; and sometimes, an extended pidgin, which has all the linguistic markers of a

creole without actually being a mother tongue. Furthermore, creolized (mother tongue)

forms of it are in wide use in Sierra Leone, where it is becoming more important than

English, and in Liberia, both of which are countries to which slaves were returned – either

from America, Canada and the West Indies or from slave ships seized by the British navy

– from the late eighteenth century on. Their first language was or became a form of

(Creole) English. This accounts for the approximately five per cent of Liberians who are

342 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

native speakers of English and the two to five per cent of Sierra Leonans who speak Krio,

the English-based creole of that country. Today, creolized forms of Pidgin English are

continuing to emerge among the children of linguistically mixed marriages in many urban

centres, especially in Cameroon and Nigeria.

Linguistically, WAPE has many parallels to the Caribbean creoles, due no doubt to

the historical connections between the two areas. Here, too, for example, the past marker

is bin; the aspect marker is a or da/de/di. The pronoun system is remarkably like that of

the Caribbean creoles as well. Nouns may be followed by d

εn to mark the plural in Liberia,

but they may also be followed by {-S}. Here, interestingly, the basilect–acrolect dimen-

sion is of less importance than semantic considerations since d

εn is used most often to

mark the plural of nouns designating humans (Singler 1991: 552–6). The pronunciation

of WAPE is, however, distinctly African, reflecting the phonology of the first languages

of its speakers. Furthermore, we also find in it numerous lexical borrowings from the

local vernaculars.

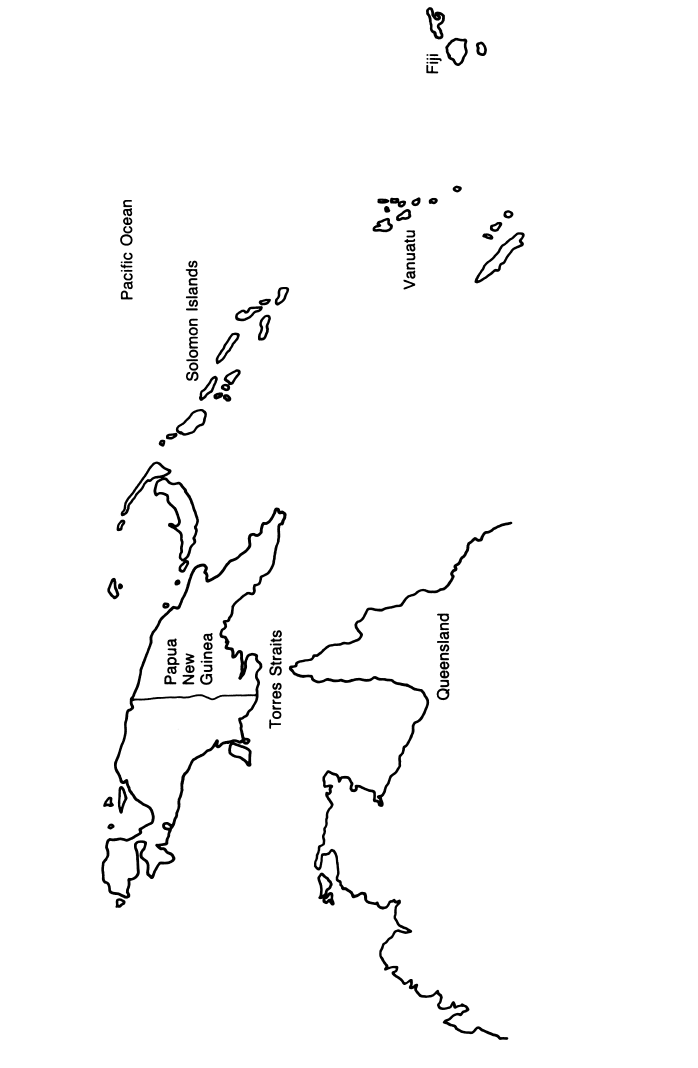

The Pacific The major focus of interest in the Pacific has been on the pidgins and

creoles of Melanesia, especially: Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea; Neo-Solomonic or

Solomon Islands Pijin; Bislama of Vanuatu (the New Hebrides); and Australian PE. There

is also increasingly more information available about Fiji. Polynesia includes the major

case of Hawaii, where Hawaii PE, Hawaiian Creole English and a spectrum of de-

creolized varieties are in use.

Fiji and Hawaii are cases in which there is a continuum similar to that of the Caribbean,

which means that there is a great deal of de-creolization. This is also the case in Australia

wherever contact with speakers of AusE is strong. Solomon Islands Pijin, Bislama and

Tok Pisin, on the other hand, are relatively independent pidgins/creoles despite the fact

that they co-exist with English as official language. In the following Tok Pisin will be

discussed in somewhat more detail.

In Papua New Guinea, Tok Pisin is the most widely used language even though English

is the official language. It is ‘the linguistically most developed and the socially most estab-

lished variety’ of the Pacific pidgins with between three quarters of a million and a million

users among the two million inhabitants of the country; some 20,000 households have it

as their first language (Mühlhäusler 1986b: 549). It is ‘a complex configuration of lects

[= varieties] ranging from unstable pidgin to fully fledged creole varieties’ (Mühlhäusler

1984: 441f.). Creolization is relatively rapid both in the towns and in non-traditional rural

work settlements. Even the majority of parliamentary business as well as university level

teaching is conducted in it as well. It is, in other words, in the process of establishing

itself independently of English.

Due to the fact that more and more people are learning English, there is some evidence

of an incipient continuum. This is most noticeable in Urban Tok Pisin (or Tok Pisin

bilong taun ‘Tok Pisin of the town’) or in Anglicized Tok Skul, where mixing and

switching between English and Tok Pisin is more frequent and especially where borrowing

from English is stronger. One of the results of this is that the mutual comprehensibility

of Urban Tok Pisin and Tok Pisin bilong ples, or Rural Tok Pisin, is becoming less

complete, to say nothing of the more distant Tok Pisin bilong bus or Bush Pidgin used

as a contact language and lingua franca in remoter areas.

Tok Pisin ultimately derives much of its vocabulary from English, but there is also

evidence of borrowing from other sources, both Melanesian (e.g. Tolai tultul ‘messenger,

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 343

Map 14.6 The Pacific Region

assistant village chief’) and European (e.g. sutman from German Schutzmann ‘police-

man’); however, the major source of new vocabulary lies within the language itself. In

this way vot, which is both a noun ‘election’ and a verb ‘vote’ is semantically transparent;

see also hevi (adj.) ‘heavy’ and hevi (n.) ‘weight’. In urban varieties numerous loan words

from StE are replacing Tok Pisin vocabulary and dispensing with native Tok Pisin means

of word formation. Under the influence of English the nouns ileksen and wait have been

introduced. Much the same thing applies when smokbalus ‘jet’ from smok ‘smoke’ and

balus ‘bird, airplane’ gives way to setplen ‘jet plane’. This process of approximation to

English is sometimes referred to as metropolitanization.

As the forms of words borrowed into Tok Pisin from English reveal, the phonologies

of the two languages differ considerably. This is most dramatically illustrated by the

convergence of English /s,

ʃ, tʃ, d/ as Tok Pisin /s/, which together with the lack of a

Tok Pisin /i/–// distinction and the devoicing of final obstruents renders ship, jib, jeep,

sieve and chief homophonous as Tok Pisin sip. Likewise, since /b/, /p/ and /f/ are not

distinguished Tok Pisin pis may be equivalent to English beach, beads, fish, peach, piss,

feast or peace. Here, of course, borrowing might profitably be employed to reduce the

number of words which are pronounced identically. Too much homophony can lead to

misunderstandings as when a member of the House of Assembly said: les long toktok

long sit nating, meaning ‘tired of talking to empty seats (sit nating)’ but was mistrans-

lated as saying ‘tired of talking to a bunch of shits’ (Mühlhäusler 1986b: 561).

The grammar of Tok Pisin has re-expanded, as is typical of elaborated and, especially,

creolized pidgins:

Verbs

i before predicates (except first and second person singular) (example: see

next);

-im marker of transitive verbs (from English him) (samting i bin katim tripela

hap ‘something divided it into three pieces’);

i gat existential there is/are (i gat tripela naispela ailan ‘there are three nice

islands’);

i stap progressive-existential marker:

– trak i stap long rot ‘The truck is on the road’

– mi stap we? ‘where am I?’

– mi stap gut ‘I am well’

– mi dring i stap ‘I am drinking’;

pínis completive or perfective aspect (after the predicate) (from English finish);

bin past marker (pre-verbal) (samting i bin katim ‘something divided it’);

bai(mbai) future marker (pre-clausal) bai mipela i save ‘we will know’;

save modal of ability (mi save rait ‘I can write’);

laik immediate future marker (trak i laik go nau ‘the truck is about to leave’);

laik ‘want to’ em i laik i go long trak ‘he wants to ride on the truck’.

Adjectives

-pela marker of attributive adjectives; only added to monosyllabic ones (naispela

‘nice’);

0

/

no adjective marker = adverb (gut ‘well’);

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 345

móa comparative marker (liklik móa ‘smaller’, gutpela móa ‘better’);

long ol superlative marker (liklik long ol ‘smallest’).

Nouns

ol plural marker (ol sip ‘the ships’);

wanpela singular article (wanpela lain ‘a line’).

Personal pronouns

Conjunctions

na and o or

tasól but, if only sapós if

The following excerpt from the story, ‘A Demon Made Three Islands’, offers a useful

illustration of some of the features just listed. Its narrator is Selseme Martina from Ais

Island, West New Britain Province; the story was modified by Thomas H. Slone (ed.) in

the collection One Thousand One Papua New Guinean Nights (Wan Tausen Wan Nait

bilong Papua New Guinea, 1996).

Text Glossary

Long [p]asis bilong Kandrian long Wes Nu bilong generalized genitive, ablative,

dative ‘of, from, for’

Briten [Provins] i gat tripela naispela ailan long generalized locative ‘at, in, on,

with, to, until etc.’

i sanap long wanpela lain tasol [Moewehafen i sanap they stand

tasol also, however

Pipel]. Tripela i wanmak na antap bilong tripela the three

wanmak the same

wan wan i stret olsem ples balus. I luk olsem wan wan each, several

ples balus (place bird) airfield

bipo ol i wanpela tasol, na wanpela samting olsem like

bipo before, once, used to

i bin katim tripela hap. hap half/halves, part(s)

By the shores of Kandrian in West New Britain [Province], there are three nice islands

that stand in a row [Moewehafen People]. The three islands are the same size. Each is

flat on top like an airfield. Before, they did not look like this. There was just one island

and something divided it into three pieces.

346 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Table 14.3 The personal pronouns of Tok Pisin

singular plural

exclusive inclusive

first person mi mipela yumi

second person yu yúpela

third person em ol

Na tru tumas, ol lapun i stori olsem. Wanpela tumas too much, very

lapun old

bikman bilong ples ol i kolim Ais [Ailan] olsem this way

bikman leader

i sindaun stori long Wantok ripota [wokman ples ol i kolim place that

they call

bilong niuspepa] i raun long dispela hap. Na stori long tell

wokman worker

wanpela lapun meri tu i sindaun long dua bilong raun about

meri woman

haus bilong em long nambis na i stori tu. Nem nambis coast, beach

bilong lapun mama ya, em Selsema Martina. ya here (= this)

This is the very truth. The old people tell the story like this. A leader from a place

called Ais [Island] sat down and told the story to a Wantok newspaper reporter [who

was around] this place. An old woman sat at the door of her house by the beach and

told it too. The name of this woman is Selseme Martina.

In Papua New Guinea as in other countries in which there is widespread use of a

pidgin/creole speakers seem to be in a permanent dilemma as to its status. The local

pidgin/creole is often not regarded as good enough for many communicative functions

and is rejected in education in favour of a highly prestigious international language such

as English. On the other hand, some people argue that such pidgins/creoles should be

espoused and developed because of their contributions to the internal integration of the

country and possible favourable effects on literacy if used in the schools. Pidgins and

creoles are certainly emotionally closer to local culture than StE. In most of the countries

reviewed in this section, there will probably be continued de-creolization. A few creoles

may stay on an independent course; most likely Sranan will, and possibly Tok Pisin,

Solomons Pijin and Bislama. Some will eventually disappear entirely: Gullah seems to

be going that way. And in many cases the status quo will surely be maintained much as

it is for an indefinite period in the future.

14.4 FURTHER READING

Ammon, Dittmar and Mattheier 1988 are a useful source on language use throughout the

world. For further details on WAfrE see: Angogo and Hancock 1980; Bamgbose 1983;

Todd 1984; for grammar: Tingley 1981; for vocabulary: especially Pemagbi 1989; for

pragmatics: Bamgbose 1983. On EAfrE: Abdulaziz 1988 gives a less Euro-centric view

than most authors; on interference from local languages see Schmied 1991; see Schmied’s

website http://www.und.ac.za/und/ling/archive/schm-01.html.

IndE Agnihotri and Khanna 1997 deal with the role of English. On pronunciation: Wells

1982; Sahgal and Agnihotri 1985; on grammar Verma 1982; on vocabulary: Nihalani

1989; Lewis 1992; Yule 1995. See also de Souza 1997. A useful, readable and compre-

hensive website on IndE (but without linguistic details) is http://www.thecore.nus.edu.

sg/landow/post/india/hohenthal/8.1.html.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 347

SingE See: Tongue 1974; Platt and Weber 1980 (vocabulary); Tongue 1974; Tay 1982;

1993; Platt 1984; 1991 (grammar); Platt and Weber 1980 (pronunciation). Ho 1993 looks

at the language continuum and substratum influences.

Philippine English Pronunciation is presented in Bautistia 1988 and Llamzon 1969

(also vocabulary).

Pidgin and creoles Useful introductions are: Hall l966; Hymes 1971a; Todd 1984;

Mühlhäusler 1986a; Holm 1988, 1989; Fasold 1990; Singh 2000. On origins see Muysken

1988 for an annotated list of nine different theories. For extensive details on the language

history of the Caribbean area, see Holm 1985. Jamaican Creole is treated in Cassidy

1961; Guyana Creole in Rickford 1987; Belize Creole in Dayley 1979. For a compar-

ison between various pidgins and creoles see Taylor 1971 and Alleyne 1980. Linguistic

and social details on individual varieties of WAPE are recounted in Barbag-Stoll 1983

for Nigerian PE; in Todd 1982 for Cameroon PE; Jones 1971 for Krio. The Journal of

Pidgin and Creole Languages (JPCL) has its website at http://www.ling.ohio-state.

edu/research/jpcl/; for The Carrier Pidgin, a newsletter see http://www.fiu.edu/~linguist/

carrier.htm. The Creolist Archives (formerly at http://creole.ling.su.se/creole/ is no

longer available; see archived material at http://creole.ling.su.se/creole/creolist/Postings.

html and http://listserv.linguistlist.org/archives/creolist.html and a re-start at http://groups.

yahoo.com/group/CreoLIST/. The Language Varieties Network at http://www.une.edu.au/

langnet/ also deals with pidgins and creoles.

348 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Bibliography of dictionaries

Note: ‘CD-ROM’ and ‘Internet’ after a title means that the work is also available on

CD-ROM and on the Internet. Dictionaries are ordered chronologically, giving the most

recent first, except for Section I.1, which is ordered by region.

I NATIVE-SPEAKER DICTIONARIES

1 National dictionaries on historical principles

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (2002), 5th edn, edited by W. Trumble and L. Brown,

Oxford: OUP (CD-ROM).

The Oxford English Dictionary Online (2000ff.), 3rd edn, edited by J.A. Simpson, Oxford: OUP

http://www.oed.com.

The Oxford English Dictionary (1989), 2nd edn, edited by J. Simpson and E. Weiner, Oxford:

OUP (CD-ROM).

The English Dialect Dictionary (1898–1905), edited by J. Wright, 6 vols, London: Frowde.

Dictionary of American Regional English, edited by F.C. Cassidy, vol. 1 (1985), vol. 2 (1991),

vol. 3 (1996), vol. 4 (2002), Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

A Dictionary of Americanisms on Historical Principles (1951), edited by M.M. Mathews, 2 vols,

Chicago, Ill.: Chicago University Press.

A Dictionary of American English on Historical Principles (1936–44), edited by W.A. Craigie

and J.R. Hulbert, 4 vols, London: OUP.

A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue (1937–2002), edited by W.A. Craigie, J. Aitken and

M.G. Dareau, Chicago: Chicago University Press; Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press;

and Oxford: OUP.

The Scottish National Dictionary (1931–76), edited by W.W. Grant and D.D. Murison,

Edinburgh: The Scottish National Dictionary Association.

The Gage Canadian Dictionary (1973), edited by W.S. Avis, P.D. Drysdale, R.J. Gregg and

M.H. Scargill, Toronto: Gage.

A Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles (1967), edited by W.S. Avis, Toronto:

Gage.

Dictionary of South African English on Historical Principles (1996), edited by P. Silva, Oxford:

OUP.

The Australian National Dictionary (1988), edited by W.S. Ramson, Melbourne: OUP.

Dictionary of New Zealand English (1997), edited by H. Orsman, Auckland: OUP.

Dictionary of Jamaican English (1980), 2nd edn, edited by F.G. Cassidy and R.B. LePage,

Cambridge: CUP.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 349

2 Comprehensive, unabridged dictionaries

The Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (1999), 3rd edn, edited by S. Steinmetz,

New York: Random House (CD-ROM).

World Book Dictionary (1992), edited by C.L. and R.K. Barnhart, 2 vols, Chicago: World Book.

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (1961; reprinted 2000), edited by P. Gove,

Springfield, Mass.: Merriam Webster (CD-ROM, Internet).

A Standard Dictionary of the English Language (1893), by I.K. Funk, New York. Later editions

published (1977) as Funk & Wagnall’s Standard Desk Dictionary, 2 vols, New York.

3 Dictionaries of new words

Oxford Dictionary of New Words (1998), 2nd edn, edited by Elizabeth Knowles and Julia Elliott,

Oxford: OUP.

Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series, (vols 1 and 2, 1993; vol. 3, 1997), edited by

J.A. Simpson, Oxford: OUP.

Fifty Years Among the New Words. A Dictionary of Neologisms 1941–1991 (1991), edited by

J. Algeo, Cambridge: CUP.

Third Barnhart Dictionary of New English (1990), edited by R.K. Barnhart, Sol Steinmetz with

C.L. Barnhart, New York: Wilson.

Oxford English Dictionary Supplement (1972–1987), 4 vols, edited by R.W. Burchfield, Oxford:

OUP.

12,000 Words: A Supplement to Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (1986), edited by

F.C. Mish, Springfield, Mass.: Merriam Webster.

9,000 Words: A Supplement to Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (1983), Springfield,

Mass.: Merriam-Webster.

The Second Barnhart Dictionary of New English (1980), edited by C.L. Barnhart, S. Steinmetz

and R.K. Barnhart, Bronxville: Barnhart/Harper & Row.

6,000 Words: A Supplement to Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (1976), Springfield,

Mass.: G. & C. Merriam.

The Barnhart Dictionary of New English since 1963 (1973), edited by C.L. Barnhart, S. Steinmetz

and R.K. Barnhart, Bronxville: Barnhart/Harper & Row.

4 Desk, college dictionaries

a) From publishers in the UK

Collins English Dictionary (2003), 6th edn, Glasgow: HarperCollins.

The New Penguin Dictionary of English (2000), edited by R. Allen, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Chambers Science and Technology Dictionary (1999), edited by P.M.B. Walker, London:

Chambers.

Chambers 21st Century Dictionary (1999, updated edn), edited by M. Robinson, London:

Chambers.

The Concise Oxford Dictionary (1999), 10th edn, edited by J. Pearsall, Oxford: OUP.

The Chambers Dictionary (1998), edited by E. Higgleton, Edinburgh: Chambers.

The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998), edited by J. Pearsall, Oxford: OUP.

The Concise Scots Dictionary (1996), edited by M. Robinson, Edinburgh: Chambers.

The Concise Ulster Dictionary (1996), edited by C.I. Macafee, Oxford: OUP.

350 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF DICTIONARIES

Larousse Dictionary of Science and Technology (1995), edited by P.M.B. Walker, New York:

Larousse.

The Longman Dictionary of Scientific Usage (1988), edited by A. Godman and E.M.F. Payne,

London: Longman.

b) From publishers in the USA

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (2003), 11th edn, Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster

(CD-ROM).

The New Oxford American Dictionary (2002), edited by F.R. Abate, New York: OUP.

The Random House Webster’s College Dictionary (2001), 2nd edn, edited by R.B. Costello, New

York: Random House.

Webster’s New World College Dictionary (2001), 4th edn, edited by Michael Agnes, Boston:

Wiley.

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2000), 4th edn, edited by J.P.

Pickert, Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin (Internet).

The Encarta World English Dictionary (1999), edited by K. Rooney, London: Bloomsbury

(CD-ROM; Internet).

Flexner, S.B. (1982), Listening to America. An Illustrated History of Words and Phrases From

Our Lively and Splendid Past, New York: Simon and Schuster (arranged according to subject

matter).

c) Other dictionaries

The Australian Oxford Dictionary (1999), edited by B. Moore, Melbourne: OUP.

The Canadian Oxford English Dictionary (1998), edited by K. Barber, Toronto: OUP.

Gage Canadian Dictionary (1997), revised and expanded, Toronto: Gage Educational.

The Macquarie Dictionary (1997), 3rd edn, edited by A. Delbridge et al. Sydney: The Macquarie

Library, Macquarie University.

The New Zealand Dictionary (1995), 2nd edn, edited by E. and H.W. Orsman, Auckland: New

House.

A Dictionary of South African English (1991), 4th edn, edited by J. Branford, Cape Town: OUP.

A Dictionary of Australian Colloquialisms (1990), edited by G.A. Wilkes, South Melbourne:

Sydney University Press.

The New Zealand Pocket Oxford Dictionary (1990), edited by R. Burchfield, Auckland: OUP.

Heinemann New Zealand Dictionary (1989), 2nd edn, edited by H.W. Orsman and C.C. Ransom,

Auckland: Heinemann.

The Australian Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English (1987), 7th edn, edited by G.W.

Turner, Melbourne: OUP.

The Dictionary of Newfoundland English (1982; with supplement 1990), 2nd edn, edited by G.M.

Story, W.J. Kirwin and J.D.A. Widdowson, Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Hawkins, P.A. (1986) Supplement of Indian Words in J. Swannell (ed.), The Little Oxford

Dictionary, 6th edn, Oxford: OUP.

5 Thesauruses

Bloomsbury Thesaurus (1997), edited by F. Alexander, London: Bloomsbury.

Webster’s New World Thesaurus (1997), 3rd edn, edited by C.G. Laird, New York: Macmillan.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF DICTIONARIES 351