Gramley, Stephan; P?tzold, Kurt-Michael. A Survey of Modern English

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The final two points distinguish Chicano English from the second language ‘interference’

variety. The predictable interference pattern would be a realization of /

ʃ/ as /tʃ/, of // as

/i/, of /e/ as /e/ and of /υ/ as /u/ since Spanish has only the latter member of each pair.

As pointed out above under 9 and 10, Chicano speakers often realize the member of each

pair which is not predicted, and this is what distinguishes such Chicano speakers from

both Mexicans and Anglos.

Various studies have shown that there are considerable obstacles in the way of general

acceptance of Chicano English as equivalent to other accents of StE. A matched guise

test, for example, in which the participants were told that all the voices they heard were

those of Mexican Americans showed a clearer association of pejorative evaluations

(stupid, unreliable, dishonest, lazy etc.) with a Chicano voice than with a near-Anglo

accent (Arthur et al. 1974: 261).

11.4.3 Black English (BEV/AAVE)

The most widely recognized and widely researched ethnic dialect of English is Black

English Vernacular, also known as African American Vernacular English. Before looking

at it more closely, it should be pointed out that many middle class Blacks do not speak

BEV/AAVE, but are linguistically indistinguishable from their white neighbours. Rather,

it is the poorer, working and lower class African Americans, both in the rural South and

the urban North, who speak the most distinctive forms of this dialect. It is often distinctly

associated with the values of the vernacular culture including performance styles espe-

cially associated with black males in such genres as the dozens, toasting, ritual insults

etc., but also chanted sermons (Abrahams 1970; Kochman 1970; Rosenberg 1970).

One of the main debates which have raged in connection with BEV/AAVE concerns

its origins. Some maintain that it derives from an earlier Plantation Creole, which itself

ultimately derives from West African Pidgin English (see Dillard 1972; Burling 1973;

Labov 1998; Rickford 1998; see also Chapter 14.3). This would mean that BEV/AAVE

contains grammatical categories (especially of the verb phrase) which are basically

different from English. The converse view is that BEV/AAVE derives from the English

of the white slave owners and slave drivers, which ultimately derives from the English

of Great Britain and Ireland. BEV/AAVE, so conceived, is only divergent from StE in

its surface forms. It is, in addition, possible to take a position in between these two, main-

taining that both have had influence on BEV/AAVE.

In evaluating the question of origins it has generally been conceded that BEV/AAVE

has a phonological system which is often greatly different from that of GenAm, though

often remarkably similar to White Southern Vernacular English. Since BEV/AAVE has

its more immediate origins in the American South, pronunciation similarities between the

two are hardly astonishing. This explains the followed shared features:

1 realization of /a

/ as [a] before voiced consonants (I like it sounds like Ah lock it);

2 convergence of // and /e/ + nasal (pin = pen);

3 merger of /

ɔ/ and /ɔ/, especially before /l/ (boil = ball);

4 merger of // and // before /ŋk/ (think = thank);

5 merger of /i(r)/ and /e(r)/ (cheering = chairing) and of /

υ(r)/ and /ɔ(r)/ (sure = shore).

262 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Furthermore, both are historically non-rhotic (though White Southern Vernacular English

is increasingly being rhoticized; see Bailey/Thomas 1998: 91), both vocalize /l/ (all =

awe), and both simplify final consonant clusters (best → bes; hand → han) (for further

points of difference and similarity, see Bailey/Thomas 1998).

It is this final point which, in the end, also distinguishes the two accents, for

BEV/AAVE carries the deletion of final consonants much further than Southern White

Vernacular does. While both might simplify desk to des’ (and then form the plural as

desses), BEV/AAVE deletes the inflectional endings {-D} and {-S} more frequently so

that looked becomes look and eats, tops and Fred’s become eat, top and Fred. Some

people have called the existence of the category of tense in BEV/AAVE into question

because the past tense marker {-D} is so frequently missing. However, the past tense

forms of the irregular verbs, where the past does not depend only on {-D}, e.g. catch –

caught or am/is/are – was/were are consistently present. Hence any conclusion about the

lack of tense would be mistaken. Indeed, the tense and aspect system of BEV/AAVE is

remarkably complex and allows its speakers to make distinctions which speakers of StE

cannot make within the grammatical system of StE (see the list below).

Furthermore, there are some remarkable grammatical differences between BEV/

AAVE and comparable forms of Southern Vernacular White English. The absence of

third person singular present tense {-S} is far reaching. One study shows 87 per cent

deletion of BEV/AAVE versus 11 per cent deletion for Southern White Vernacular

(Wolfram 1971: 145; see also Fasold 1986: 453f.). Consequently, it is not unreasonable

to conclude that it is not well anchored in BEV/AAVE (‘AAVE shows no subject-verb

agreement, except for present-tense finite be’ Labov 1998: 146). This, of course, is not a

terribly serious loss since there is no potential confusion of meaning as there can be when

{-D} is lost. With plural {-S}, which does carry important meaning, there is much less

frequent deletion than with the verb ending {-S} (Fasold 1986: 454).

A number of grammatical features specific to BEV/AAVE have been pointed out. They

include

1 stressed béen (sometimes given as bín) as a marker of the remote past (e.g. The

woman béen married, which does not mean ‘The woman has béen married (but no

longer is)’, as a StE speaker might assume, but indicates something which happened

in the more distant past and whose results are in effect: ‘The woman has been married

a long time’ (see Martin and Wolfram 1998: 14; Green 1998: 46f.; Labov 1998:

§5.5.4);

2 non-finite be as a marker of habitual aspect, e.g. he be eating ‘he is always eating’

(see e.g. Green 1998: 45f.; Labov 1998: §5.5.1 gives a slightly different view); this

stands in contrast to he eating ‘he is eating (right now)’;

3 perfective done (sometimes given as d

ən) for perfective or completive aspect as

when an event has taken place and is over (even though its effects may still be in

effect), e.g. they done washed the dishes ‘they have already washed the dishes’; like

the StE present perfect this form does not co-occur with past adverbials nor with

stative verbs (see e.g. Green 1998: 47f.; Labov 1998: §5.5.2);

4 sequential be done, often as a future resultative marker, shows one of several possi-

bilities of combining the aspectual markers just given, e.g. I’ll be done killed that

motherfucker if he tries to lay a hand on my kid again ‘I’ll kill him if he should try

to hurt my kid’ (Labov 1987: 7f.; 1998: §5.5.3);

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 263

5 no or infrequent third person singular present tense {-S} as explained above;

where the verb be appears as an inflected form we find I + am, but you, he/she/it,

we, y’all, they + is (Green 1998: 42);

6 third person singular present tense {-S} used as a marker of narrative in contrast

to unmarked non-narrative usage; this is viewed as a recent development (Labov

1987: 8f., but see 10.2.2. for a similar feature in Scots);

7 the past and the past participle are frequently identical, e.g. I ate ‘I ate’ or ‘I have

eaten’; the two are distinguished when emphatic (I

DID

eat vs I

HAVE

ate) or when

negated (I didn’t eat vs I ain’t/haven’t ate) (Green 1998: 40f.);

8 some young speakers form the simple past of a verb using had + lexical verb as in

I had got sick ‘I got sick’) (ibid.: 43);

9 relative clauses (virtually exclusively defining ones, since non-defining relatives

are typical of rather formal, especially written language) are seldom formed using

who, which and whose; zero relative is preferred, even when the relative element

is the subject of the relative clause, e.g. That’s the man [0

/

] come here the other day

(Mufwene 1998: 76f.);

10 plural marker and demonstrative them is widely used (as elsewhere in non-standard

English), e.g. them/dem boys; this includes what is known as the associative plural,

a form of them added to a definite noun, e.g. Felicia nem (< and them) done gone

‘Felicia and the others have already gone’ (Mufwene 1998: 73);

11 negative concord (also known as multiple negation or pleonastic negation) allows

not just one single negation, as in StE, but permits the negation to be copied onto

all the further indefinite (so-called negative polarity items), even in cases where the

negation is copied onto a subordinate clause as in He don’t think nothing gonna

happen to nobody because of no arguments (Martin/Wolfram 1998: 23);

12 question formation may occur without inversion both in indirect questions, e.g. They

asked could she go to the show, and in direct questions (though less frequent), e.g.

Who that is? Why she took that? (ibid.: 27ff.);

13 double modals (as are frequently used in Southern AmE), e.g. I might could of

(= have) gone.

The most discussion has centred around what is called non-finite or invariant or

distributive be (2 in the preceding list). In order to understand what this is, it is first

necessary to note that there are two distinct uses of the copula be in BEV/AAVE. The

one involves zero use of the copula, e.g. She smart = ‘She is smart’, which describes a

permanent state or She tired ‘She is tired’, which names a momentary state. Here collo-

quial white English might use a contraction (She’s smart); BEV/AAVE may be thought

of as deleting instead of contracting. Where contraction is not possible in StE, neither is

deletion in BEV/AAVE, e.g. Yes, she really is. Invariant be, in contrast, is used to describe

an intermittent state, often accompanied by an appropriate adverb such as usually or some-

times, e.g. Sometimes she be sad.

The major question is where this form comes from (origins again). It seems that

invariant be does not occur in the most extreme creoles, though it does in some de-

creolized forms. Therefore they are an unlikely source. Some studies of White Southern

Vernacular: (a) show it to be rare; and (b) do not indicate clearly whether it carries the

same meaning as in BEV/AAVE or whether it is not merely an instance of will/would be

in which ’ll or ’d have been deleted (Feagin 1979: 251–5). The White Vernacular is there-

264 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

fore also not a very likely source of this construction. One investigation of southern

BEV/AAVE even reveals it to be something of a rarity there, too (Schrock 1986: 211–14).

However, the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States turns up instances of it in both black and

(a very few instances of) white vernacular speech. In this data invariant be sometimes

represents deletion of will and would, but more often it is used for an intermittent state

(including negation with don’t: Sometime it be and sometime it don’t) and, with a

following present particle, for intermittent action (How you be doing?) (Bailey and Bassett

1986). If invariant be is an innovation of BEV/AAVE, then this would speak for an

increasing divergence of BEV/AAVE from white vernacular forms. This question has

been hotly, but inconclusively, debated (American Speech 1987; see also Butters 1989).

Whatever its source may actually be, invariant be is a construction that speaks strongly

for the status of BEV/AAVE as an independent ethnic dialect of English.

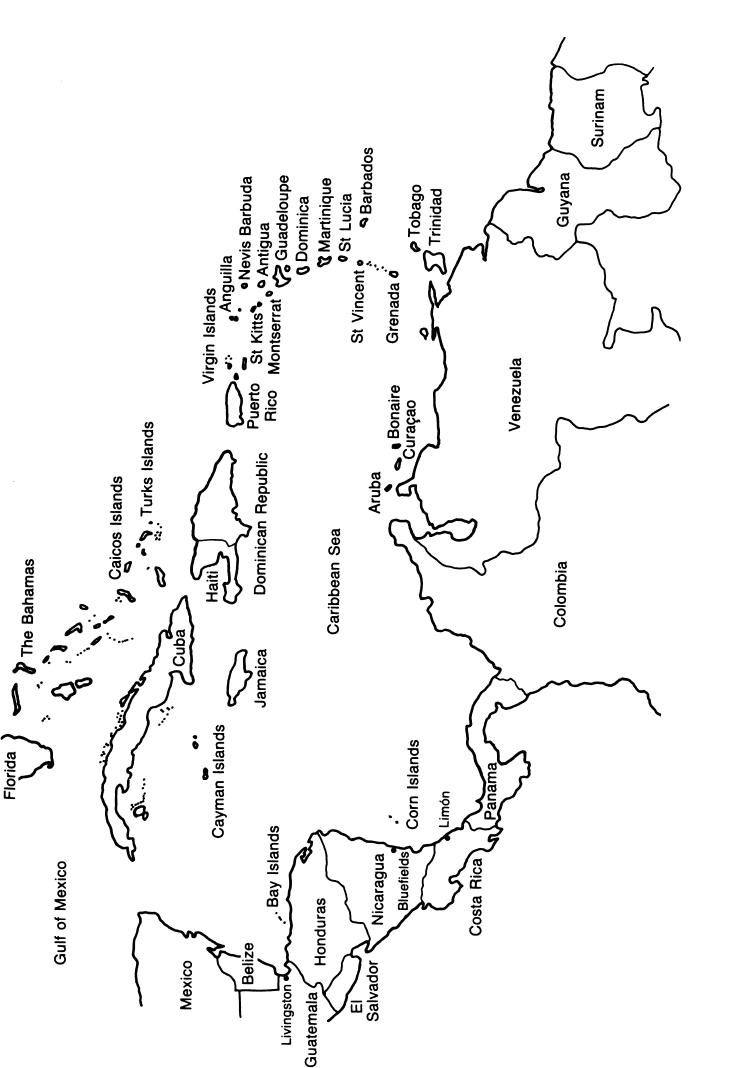

11.5 THE LANGUAGES OF THE CARIBBEAN

The Caribbean stretches over a wide geographical area and includes, for our purposes, at

least 19 political units which have English as an official language (see Map 11.3):

Anguilla, Antigua-Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, the British Virgin Islands,

the Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, Puerto Rico (with

Spanish), St Kitts-Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent, Trinidad-Tobago, the Turks and Caicos

Islands and the American Virgin Islands. In addition to these countries and territories

there are numerous others with Spanish as the official language (Costa Rica, Cuba,

Columbia, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama,

Puerto Rico (with English) and Venezuela), as well as a few with French (Guadeloupe,

Haiti, Martinique) and Dutch (Aruba-Bonaire-Curaçao and Surinam). Although the

majority of the islands are anglophone, the largest are not (Cuba and Hispaniola [the latter

with the Dominican Republic and Haiti]); and Puerto Rico is chiefly Spanish speaking.

The mainland all the way from Guyana to the United States is hispanophone with the

exception of Belize. In the sub-US Caribbean the 5 to 6 million inhabitants of the anglo-

phone countries are greatly outnumbered by their Spanish speaking neighbours.

Below the level of official language policy lies the linguistic reality of these countries.

Here English is truly a minority language, for the vast majority of people in the anglo-

phone countries are speakers not of StE or even GenE, but of English creoles. In addition,

Guyana and Trinidad-Tobago have a number of Hindi speakers. Guyana also has

Amerindian language speakers. Belize has Amerindian as well as Spanish speakers.

Spanish is used by small groups in the American Virgin Islands and Jamaica. French

Creole is widely spoken as a vernacular in Dominica and St Lucia as well as by smaller

groups in the American Virgin Islands and Trinidad-Tobago. English creoles are,

however, the major languages on most of the anglophone islands; furthermore, they are

in use on the Caribbean coast of several Central American countries besides Belize.

English creoles refer to vernacular forms which are strongly related to English in the

area of lexis, but which diverge from it syntactically, so strongly, in fact, that it is not

unjustified to regard them as separate languages rather than dialects of English (see 14.3).

The various English creoles not only share a similar historical development; in addition,

migration patterns between the various Caribbean countries as well as with West Africa

may have further heightened their mutual resemblance. More recently migration to and

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 265

Map 11.3 The Caribbean

from the US, Canada and Great Britain have had an added unifying factor for many

West Indians. Furthermore, tourism has increased exposure to AmE speech. Despite all

of this the various English creoles are, in actual fact, often so different that mutual com-

prehension between, for example, Guyana and Barbados cannot be taken for granted,

sometimes not even between StE speakers and creole speakers within a single country

such as Jamaica.

The explanation lies in the fact that each of the territories has its own history. In the

case of Barbados, for example, the vernacular has de-creolized more strongly than the

relatively conservative varieties of Guyana and Jamaica. Special factors influencing

Barbados are the higher rate of British and Irish settlers in the early colonial period,

the greater development of the infrastructure and relatively small size of the island, and

the high degree of literacy (97 per cent). Jamaica, in contrast, received slave imports for

a much longer period than Barbados; this led to a lengthening of the pidgin phase and a

subsequent strengthening of the creole. Guyana is linguistically similar to Barbados

because there was a great deal of immigration there from Barbados. However, besides its

black population Guyana also has an approximately equal number of East Indians (most

of whom have, in the meantime, adopted the creole for daily use); their arrival (between

1838 and 1924) slowed down the de-creolization process by acting as a buffer between

the StE top of society and the creole bottom.

11.6 THE LINGUISTIC CONTINUUM

Regardless of whether the various English creoles are more or less mutually comprehen-

sible, more or less creolized, they all have one thing in common: all of them are

diglossically Low languages in relation to the High language, which is StE in the anglo-

phone countries, Dutch in Surinam and Spanish in Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and

Columbia. This means that StE (and Dutch and Spanish) are used in government admin-

istration and state schools (although changes are in progress in the direction of more use

of the creoles, especially in Belize, Jamaica and Trinidad). StE dominates in most of the

printed media and all but a little of the electronic media. The creoles are the language of

everyday life, the home, family and neighbourhood. Church sometimes uses the vernac-

ular, sometimes the High language. Literature makes a few forays into creole. Only

Sranan, a creole relatively distantly related to English, is used widely for literary (and

religious) purposes.

If it is not unjustified to regard the English creoles as separate languages, as remarked

above, it is also not fully justified to do so. Many people see StE and the creoles as two

extremes related through a spectrum or continuum of language varieties, each of which

is only minimally different from the nearest variety upward or downward from it on the

scale. The lowest or broadest form is called the basilect; the highest, StE, the acrolect.

In between lie the mesolects, which are any of numerous intermediate varieties. Evidence

of a linguistic nature indicates, however, that there is a fairly strong, perhaps substantial

break between the basilect and the mesolect. The underlying grammatical categories

shared by the mesolect and the acrolect (though realized in distinct forms) are essentially

different from those of the basilect (see below for exemplification).

The basilect lacks overt prestige while the acrolect commands respect. The lower a

person’s socio-economic status and the poorer his or her education, the more likely that

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 267

person is to speak the basilect. Rural dwellers will also be located closer to the basilect

than the urban part of the population. Age is an additional factor, since younger speakers

generally seem more likely than older ones to adopt the more standard forms, which,

however, need not be all the way up to the level of StE.

Despite the overt prestige of the acrolect, individual and group loyalties may lead to

more use of basilect for some speakers. There are covert local norms which favour creole

language and culture. Indeed, certain speech genres, especially those associated with

performance styles, can hardly be imagined apart from the vernacular: teasing, riddles,

traditional folk tales such as the Anansi stories with their spider hero, ritual insults and

the like (see also similar uses in BEV/AAVE). Furthermore, the forms people use with

one another may be a good indication of both where they feel they belong on the social

scale and how they feel towards their conversational partners:

The speaker of Jamaican creole who controls a substantial segment of the linguistic

spectrum on the island knows when he meets an acquaintance with the same control

speaking with another speaker who controls a lesser range, that if his friend uses

nyam and tick he is defining the situation on the axis of solidarity and shared iden-

tity whereas if he is using eat and thick he is interested in the maintenance of social

distance and formality.

(Grimshaw 1971: 437)

The continuum is not the same in all the territories mentioned. The English of

Barbados, Trinidad and the Bahamas is so de-creolized that it is possible to say there

is, relatively speaking, no basilect. In countries where English is not the official

language, the opposite might be said to be the case: there is no acrolect. This is actually

the case only for Surinam, where Sranan has gone its own way, no longer oriented

towards English.

11.7 LINGUISTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF C

ARIB

E

StE in the Caribbean area is syntactically the same as other standard varieties. Where

there are BrE–AmE differences CaribE is oriented towards BrE; only in the American

Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico – to the extent that English is spoken in the latter – is

AmE the model. The creole forms, on the other hand, offer an enormous contrast in

grammar (see 14.3).

The vocabulary of CaribE contains a considerable number of terms not widely known

outside the area. Inasmuch as its speakers move easily between the acrolect and the

mesolect, it is only natural that standard CaribE draws on these lexical resources. The

special regional (or subregional) vocabulary of the Caribbean draws ultimately on two

major sources: the African languages of the slaves and non-standard regional English of

the early settlers from Britain and Ireland. A number of creole words of Scottish origin

have become part of standard CaribE, e.g. lick ‘to hit, strike’, dock ‘to cut the hair’, heap

‘a great deal’. Examples of Africanisms tend to be calques (loan translations) rather than

direct borrowings. For example, eye water ‘tears’, sweet mout’ ‘flatter’ and hard ears

‘persistently disobedient, stubborn’. Reduplication (little-little ‘very small’) is also prob-

ably an African carry-over. An example of a direct borrowing from an African language

268 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

is John Canoe, the term for the mumming parade at Christmas time. Its source is the Ewe

language, but re-analysed after the fashion of folk etymology. Cassidy explains it as

follows:

The chief dancer in the underlying African celebration seems to have been a medicine

man, and in Ewe we find dzonc ‘a sorcerer’, and kúnu ‘a cause of death’, or alter-

natively dzonkc ‘a sorcerer’s name for himself’, and -nu, a common suffix meaning

‘man’. Some African form or forms of this kind meaning ‘sorcerer-man’ has been

rationalized into John Canoe.

(Cassidy 1986: 137)

There are two norms, a local one and StE. ‘Despite consciousness of two different

norms within each of the relevant territories, there is, in reality, no simple juxtaposition

of unrelated language varieties in any of them. The continued influence of English

throughout the years has blurred the distinction between what must once have been more

easily separable varieties’ (Christie 1989: 247). Here are some examples from Christie:

scratch ‘itch’ (My hand is scratching me)

care ‘care for’ (Care your books)

Word with counterparts in StE generally known in CaribE:

foot-bottom ‘sole’ (The corns on my foot-bottom are painful)

hand-middle ‘palm’ (Show me your hand-middle and I’ll tell your fortune)

Words with additional meanings or different ones:

hand ‘arm, hand’ (She has her left hand in a sling)

tail ‘hem’ (The tail of her dress has come loose)

Words belonging to a different grammatical category:

grudge ‘envy . . . for’ (The woman grudge me my big house)

sweet ‘give pleasure to’ (The joke sweets him)

Collocations:

best butter ‘butter’ (I don’t want margarine. I must have best butter)

tall hair ‘long hair’(John’s girl-friend is the one with tall hair)

Idioms:

work out ‘outside the home’ (Since my parents work out, I go to me aunts)

keep a party ‘have one’ (John kept a party at his house on Friday)

Intra-regional differences in lexis:

trace (Trinadad-Tobago) = gap (Barbados) = lane (Jamaica) ‘narrow street’

callaloo a different stew (crab meat and leafy vegetables) in Trinadad-Tobago

from the spinach-like plant and soup made from it in Jamaica

The pronunciation of CaribE marks it as regional more than anything else. Here the

carry-over between basilect and acrolect is especially prominent. One of the most notice-

able features is the stressing, which gives each syllable more or less equal stress (syllable

timing). In addition, in a few cases pitch may play a decisive role in interpreting a lexeme;

kyan with a high level tone is positive ‘can’, while the same word with a high falling

tone means ‘can’t’.

The consonants in comparison to RP and GenAm include the following particularly

noticeable differences:

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 269

1/θ/ and /ð/ are freely, but not exclusively realized as [t] and [d] (tick for thick; dem

for them);

2 /v/ may be a [b] or a bilabial fricative [

β] (gib for give, bittles for vittles);

3 the ending {-ing} is regularly /-

n/ (talkin’);

4 simplification of consonant clusters, especially if homorganic and voiced after /n/

and /l/ (blind → blin’); in the basilect even initial clusters are sometimes simplified

(string → tring)

5 palatalization of /k/ and /g/ + /a

/: car /kjar/

6 clear /l/ in all phonetic environments

Some territories are rhotic (Barbados); some are non-rhotic (Trinidad, the Bahamas);

and some are semi-rhotic, i.e. stressed final r as in near is retained (Jamaica, Guyana)

(Wells 1982: 570); in the basilect /r/ is sometimes realized as [l], flitters for fritters, but

this is becoming less common.

The vowels differ most vis-à-vis RP and GenAm. In Jamaica, for instance, /e

/ and

/

əυ/ are the monophthongs [e] and [o]. // is realized as [a], which is also the realiza-

tion of /

ɒ/, so that tap and top are potential homophones. Both are distinguished by length

from the vowel of bath [a

]. Central vowels are less a fixed part of the system; hence

schwa is often [a] as well as [e]; /

/ may be back and rounded; and // may be [o] (e.g.

Jamaican Creole boddem ‘birds’). In the basilect /

ɔ/ sometimes merges with /a/, making

boy and buy homophones.

11.8 FURTHER READING

Algeo 2001b and the articles in it (several listed below) cover a great many aspects of

North American English. See also Schneider 1996 and McArthur 2002. For a history

of AmE, see Dillard 1993. For a summary of the varied history of the term General

American, see Van Riper 1986. Lippi-Green 1997 looks at attitudes towards English

accents, American and other. A reasonable sample of contributions to variation study in

North American English is Glowka and Lance 1993; see Pederson 2001 on American

dialects. The vocabulary of AmE is entertainingly presented in Flexner and Soukhanov

1997; see also Cassidy and Hall 2001; and Lighter 2001 on slang as well as Bailey

2001 on AmE abroad. Gallegos 1994 deals with the movement to establish English as

the official language of the US. The website of the American Dialect Society http://

www.americandialect.org/ offers a great deal of information on American English.

See also http://us.english.uga.edu/ and http://polyglot.lss.wisc.edu/dare/dare.html for the

Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE). The Phonological Atlas of North

America can be accessed at http://www.ling.upenn.edu/phono_atlas/home.html.

For CanE see: Edwards 1998; Brinton and Fee 2001; The Canadian Oxford English

Dictionary (1998). The Dictionary of American Regional English (1985, 1991, 1996) lists

regional vocabulary. See also the Longman Dictionary of American English (1997).

Cities in which sociolinguistic studies have been carried out include: New York (Labov

1972a); Detroit (Shuy et al. 1967); Philadelphia (Labov et al. 1972); and Anniston,

Alabama (Feagin 1979). Butters 2001 treats vernacular AmE. Kroch 1996 is a rare study

of upper class speech.

270 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Native American English is treated in Leap 1993. Spanish influenced English is dealt

with in contributions by García and Otheguy, Valdés, and Zentella in McKay and Wong

1988. A recent collection of contributions on BEV/AAVE is Mufwene et al. 1998, which

contains Martin and Wolfram; Green; Mufwene; Labov; Rickford; Bailey and Thomas,

all quoted in §11.4.3; see also Rickford and Rickford 2000. Wolfram and Clarke 1971 is

older, but contains a readable collection of articles dealing with both sides of the question

of the origins of BEV. For a good non-technical introduction and a compromise view of

BEV origins see Burling 1973. On consonant deletion: see Fasold 1972; this also treats

invariant be, as does Feagin 1979. Dozens, toasting, ritual insults etc. are well treated in

Abrahams 1970 and Kochman 1970; for chanted sermons see Rosenberg 1970. The ques-

tion of the convergence or divergence of BEV and white vernacular English is discussed

in ‘Are Black and White Vernaculars Diverging?’, American Speech 62 (1987): 1–80;

and in Butters 1989. A possible entry to BEV/AAVE is http://www.arches.uga.edu/

~bryan/AAVE/.

A general treatment of CaribE is Holm 1994. For more on the spread of English in the

Caribbean see Holm 1985. The pronunciation of CaribE is treated in Lawton 1984: 257

and Wells 1982. Roberts 1988 is a non-technical treatment which contrasts the features

of the major territories grammatically, lexically and phonetically. Chapter 14 deals with,

among other things, English creoles in the Caribbean. Two links to Jamaican Creole

are http://www-user.tu-chemnitz.de/~wobo/jamaika.html and http://www.jamaicans.com/

speakja/glossary.htm.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 271