Gramley, Stephan; P?tzold, Kurt-Michael. A Survey of Modern English

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The intelligibility argument When, early in the century, Jones chose RP as the basis

for his description of English pronunciation, one of his arguments was that RP and near-

RP are easily understood almost everywhere that English is spoken. It is certainly true

that RP is frequently heard in the media and is therefore easily accessible to many students

of English as a foreign language (EFL). Furthermore, familiarity helps to guarantee

comprehensibility. Yet this should not be overvalued, for in the words of Trudgill,

‘Differences between accents in the British Isles are hardly ever large enough to cause

serious comprehension difficulties’ (1975: 53). In addition, it is conceivable that people

in parts of the world where RP is not familiar (particularly in the sphere of influence of

AmE) might find RP less intelligible than GenAm.

The scholarly treatment argument RP has long been the basis of linguistic treat-

ments of English pronunciation and has been used in EFL teaching materials (including

tape recordings and pronunciation exercises) to a degree that far outdistances any other

accent. Hence for purely practical purposes RP has a lot to recommend it. Material based

on other accents, mainly GenAm, is also available. Most teachers see the advantage in

using a single standard in the initial stages of EFL teaching, whichever it is, but few

would dispute the necessity of exposing more advanced students to both RP and GenAm,

at least, and preferably to other important accents as well.

The social argument As the introductory remarks to this section indicate, RP does

have social associations. While it is not exclusive to any particular class, it is, nonethe-

less, typical of the upper and the upper middle classes. In sociolinguistic studies such as

that of Trudgill in Norwich it has become clear that RP is the overt norm in pronuncia-

tion for most of the middle class (and especially for women). On the other hand, in

Norwich local speech forms and London vernacular forms were said to be the covert

norms in the working class (particularly strongly among men; see also 9.2.3). This fact

should not be lost on the foreign learner, who needs to be aware of the connotations of

accent within English society, not only to understand how the English see (hear) each

other, but also to realize what the accent he or she has learned may suggest to his or her

interlocutors.

In actual fact people seldom choose an accent. Rather, they have one. (EFL students,

of course, get one – initially, at least, their teacher’s.) What counts is the norms of the

group they belong to or identify with. People have the accent they have because they are

where they are in society. However, a few who move up in society ‘modify their accent

in the direction of RP, thereby helping to maintain the existing relationship between class

and accent’ (Hughes and Trudgill 1996: 8).

In other words, some people aspire to ‘talk better’ and are or are not successful; others

disdain this as ‘talking posh’ or using a ‘cut-glass accent’. Just how strong the social

meaning of accent is has been repeatedly confirmed by investigations designed to elicit

people’s evaluations. In so-called matched guise tests subjects were asked to rate speakers

who differed solely according to accent (often the speaker was one and the same person

using two or more accent ‘guises’). The general results of such tests reveal that in Britain

RP has more prestige vis-à-vis other accents, is seen as more pleasant sounding, that its

speakers are viewed as more ambitious and competent, and as better suited for high status

jobs. On the other hand, RP speakers are rated as socially less attractive (less sincere,

trustworthy, friendly, generous, kind). It is reported, for example, that the content of an

232 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN THE BRITISH ISLES 233

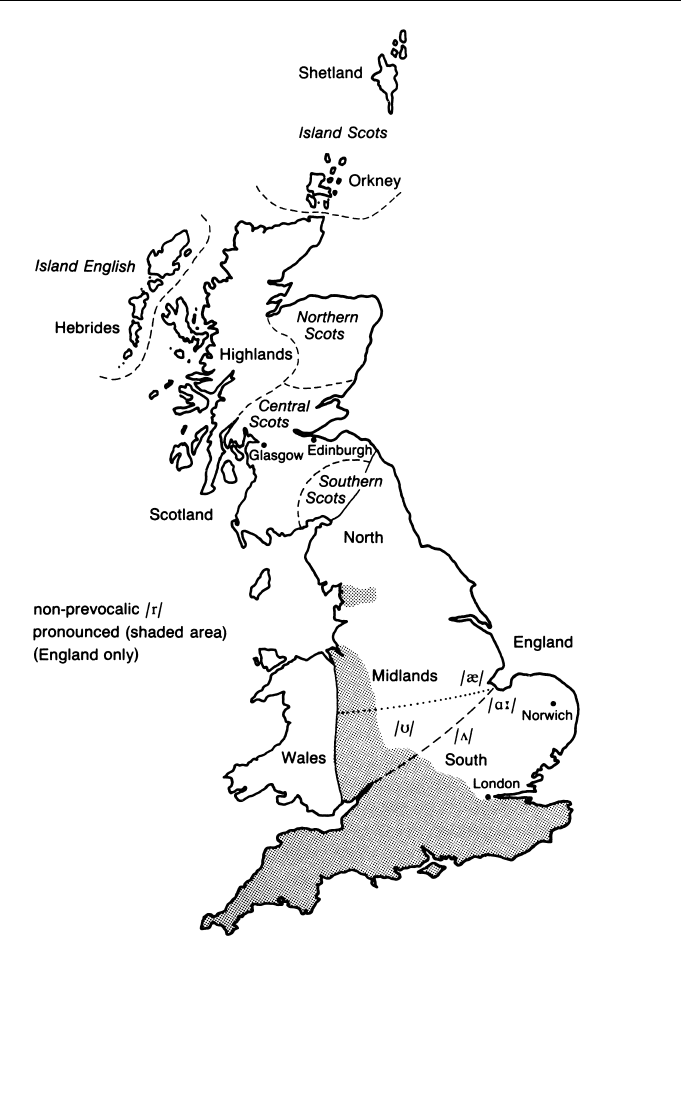

Map 10.1 Great Britain

argument on the death penalty, identically formulated, but presented in four different

accent guises, was more positively evaluated in the RP as opposed to three non-RP guises.

Interestingly enough, the regional voices were, nevertheless, more persuasive (Giles

and Powesland 1975: 93). Other experiments showed that people are more willing to

comply with requests (e.g. filling out questionnaires, including the amount of written

information provided) that are framed in an RP accent. Such results indicate the type of

danger involved here. The expectation is that a distinctly non-RP accent may signal lack

of competence and authority, an attitude hardly justified in times such as these when

education is no longer a class privilege. What is even less justified is the expectation of

many teachers that children with the ‘right’ accent who use StE are more intelligent or

capable than those with a local accent and non-standard GenE forms. Yet no investiga-

tions have indicated that the use of non-prestige forms correlates with less intelligence or

capability. What they do correlate with is class. Of course, imparting knowledge about

the social evaluation of language is a legitimate educational goal, but this is different

from wasting time trying to eliminate non-prestigious speech forms well anchored in

regional peer groups. The latter is unlikely to meet with success. The need is really for

greater linguistic tolerance in society coupled with more widespread training to a reason-

able level of competence in StE, which is becoming absolutely necessary for more

and more jobs.

10.2 SCOTLAND

10.2.1 The languages of Scotland

The move from England to Scotland (population: just over 5 million) is one of the linguis-

tically most distinct that can be made in the British Isles as far as English is concerned.

StE itself is well established throughout Scotland in government, schools, the media, busi-

ness etc. in the specifically Scottish variety of the standard, which is usually referred to

as Scottish Standard English (SSE). Yet in many areas of everyday life there is no

denying that forms of English are used in Scotland which are often highly divergent from

the English of neighbouring England. These forms are ultimately rooted in the rural

dialects of the Scottish Lowlands, which differ distinctly from the dialects south of the

Border: there is ‘a greater bundling of isoglosses at the border between England and

Scotland . . . than for a considerable distance on either side of the border (Macaulay 1978:

142). (Note: an isogloss represents the boundary line between areas where two different

phonetic, syntactic or lexical forms are in use.) The traditional rural dialects as well as

their urban variations are collectively known as Scots.

Besides SSE and Scots one further non-immigrant language is spoken in Scotland.

That is Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language related to both Welsh and Irish. At present only

a small part of the population (no more than 1.5 per cent) speaks Gaelic; the Gaelic

language areas are located in the more remote regions of the northwest and on some of

the Hebrides. Since 40 per cent of Gaelic native speakers live today in urban (= English

language) Scotland, their continued use of the language is questionable. However, the

situation of Gaelic has stabilized somewhat since the 1960s largely due to: the teaching

of Gaelic in schools; bilingual primary education; the Gaelic playground movement;

234 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Gaelic residential areas in Glasgow, Inverness, Skye, Lewis etc. Those who speak Gaelic

are, in any case, bilingual and also speak English; their English is often influenced by

their Celtic substratum (see 10.2.3).

10.2.2 Scots

Scots is frequently seen as slovenly and does not enjoy high overt prestige. While the

language is undoubtedly widely used,

social pressures against it are so strong that many people are reluctant to use it or

have actively rejected it. . . . The only use of it made regularly by the media is for

comedy. . . . [It] is repeatedly associated with what is trivial, ridiculous and often

vulgar.

(McClure 1980: 12)

While this statement is valid, it is also necessary to note that there are several different

types of Scots, each with a different status and prestige. The variety so often and so

subjectively regarded as vulgar is urban working class Scots; considerably more positive

are the often romanticized rural dialects; a third type is literary Scots (sometimes termed

Lallans, ‘Lowlands’). This final variety is also sometimes pejoratively referred to as

synthetic Scots because it represents an artificial effort to re-establish a form of Scots as

the national language of Scotland and as a language for Scottish literature (much as was

the case before the union of the crowns in 1603, when James VI of Scotland became

James I of England, which eventually resulted in a linguistic reorientation of Scotland

towards England).

Scots is commonly subdivided into four regional groupings. Central Scots runs from

West Angus and northeast Perthshire to Galloway in the southwest and the River Tweed

in the southeast. It contains both Glasgow and Edinburgh and includes over two thirds

of the population of Scotland; it also includes the Scots areas of Ulster (see 10.3.2).

Southern Scots is found in Roxburgh, Selkirk and East Dumfriesshire. Northern Scots

goes from East Angus and the Mearns to Caithness. Island Scots is the variety in use on

the Orkney and the Shetland Islands. The Shetlands are further distinguished by the

continued presence of numerous words which originated in Norn, the Scandinavian

language once spoken in the Islands (see Map 10.1).

The situation of Scots vis-à-vis SSE may be usefully summarized with regard to its

historicity, its standardization, its vitality and its autonomy, all criteria useful in assessing

language independence (see Macafee 1981: 33–7 for aspects of the following).

The historicity of Scots as the descendant of Old Northumbrian is clearly given, and

Scots is consequently a cousin of the English of southeastern England, which was the

basis of StE. Of course, Scots has been highly influenced by StE, not least in the form

of the King James (Authorized) Version of the Bible (1611). Perhaps it is the success of

the English Bible which has inspired the various more recent translations of the Scriptures

into Scots (see Lorimer 1983). Lallans, as a language with literary ambitions, has drawn

heavily on the older Scots language for much of its vocabulary, but this is not a natural

process and the words it has adopted have no real currency, for few will seriously use

scrieve rather than write or leid rather than language.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN THE BRITISH ISLES 235

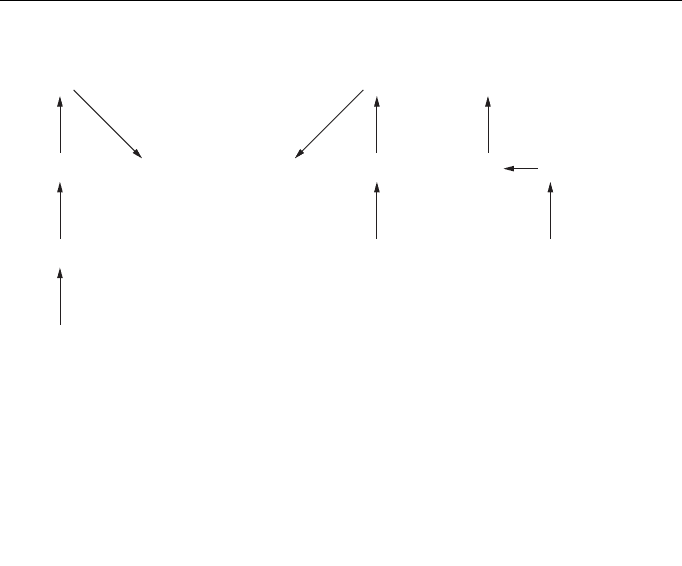

Part of the difference between English and Scots is due to changes in the long vowel

system in the period between Middle and Early Modern English, known as the Great

Vowel Shift (GVS). This shift ran differently in southern England from in northern

England and Scotland. While the long front vowels changed in much the same manner

in both places, the long back ones did not, giving us a fronted vowel [ø

] in good and

leaving [hu

s] for house unchanged (see Figure 10.1)

Standardization is the goal of the creators of Lallans, but the tendencies of its cham-

pions are to reject as vulgar the Scots forms which have the most vitality or actual

currency in everyday speech, namely those of the urban working class. A limited amount

of success within the Lallans effort has been achieved in the area of standardization of

spelling.

For good, a Glaswegian says ‘guid’, a Black Isle speaker ‘geed’, a northeasterner

‘gweed’, and a man from Angus or the Eastern borders ‘geud’, with the vowel of

French deux, but each could readily associate the spelling guid with his own local

pronunciation.

(McClure 1980: 30)

In a similar fashion <aa> is widely accepted as the spelling of either Central Scots /

ɔ/

or Northern /a/ as in ataa ‘at all’. But note that the common word /ne/ ‘not’ is spelled

either as na or as nae.

The autonomy of the Scots dialects is, in general, least visible in vocabulary, for

virtually all Scots speakers have long since orientated themselves along the lines of

236 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

front vowels

(England and Scotland)

Examples of the shift:

time [i] → [e]

teem [e] → [i]

team [ε] → [e]

tame [a] → [ε]

foul [u] → [oυ]

fool [o] → [u]

foal [ɔ] → [o]

house = hus [u]

good [o] → [ø()] or [i]

foal [ɔ] → [o]

i

e

e

ε

a

back vowels

(S. England)

u

o

oυ

ɔ

(North and Scotland)

uy

oø

ɔ

Figure 10.1 The Great Vowel Shift (GVS) in southern England and in northern England

and Scotland

English, even though Scots has retained numerous dialect words such as chaft ‘jaw’, lass

‘girl’, ken ‘know’, or ilka ‘each, every’. The lack of a Scots standard is also reflected in

the fact that there is sometimes a variety of local words for the same things, e.g. bairn,

wean, littlin, geet (‘child’) or callant, loon, chiel (‘boy’), or yett, grind (‘garden gate’)

without there being any generally recognized Scots word.

More divergent, and hence more autonomous, are some of the grammatical forms.

Among these note, for example, such non-standard morphology as the past and past

participle forms of the verb bake, namely, beuk and baken or those of work, where both

forms are wrocht (sometimes also spelled wrought). A few words also retain older plural

forms: coo ‘cow’, plural kye ‘cows’ (see English kine), soo ‘pig’ (see StE sow), plural

swine ‘pigs’, or ee ‘eye’, plural een ‘eyes’.

The second person pronoun often retains the singular–plural distinction either using

thou/du vs ye/yi/you or yiz/youse. Instead of StE relative whose one may find that his or

that her. Furthermore, the demonstratives comprise a three way system: this/that/yon

and here/there/yonder (for close, far and even further). Prepositions beginning with be-

in StE often begin with a- in Scots, so afore, ahind, aneath, aside, ayont and atween. The

verb is negated by adding na(e) to the auxiliary, e.g. hasna(e), dinna(e). Furthermore, the

auxiliaries are used differently; for example, shall is not present in Scots at all.

The syntax of Scots includes the possibility of an {-S} ending on the present tense

verb for all person as a special narrative tense form, e.g. I comes, we says etc. (see 11.4.3

for a similar feature in American Black English).

The pronunciation of Scots, finally, is also tremendously important in defining its

autonomous character. Quite in contrast to the other varieties of English around the world,

‘Scots dialects . . . invariably have a lexical distribution of phonemes which cannot be

predicted from RP or from a Scottish accent [i.e. SSE]’ (Catford 1957: 109). By way of

illustration, note that the following words, all of which have the vowel /u/ in SSE, are

realized with six different phonemes in the dialect of Angus: book /

υ/, bull //, foot //,

boot /ø/, lose /o/, loose /

υ/ (ibid.: 110).

The list given below enumerates some of the more notable features of Scots pronun-

ciation:

• /x/ in daughter; in night it is [ç]

• /kn-/ in knock, knee (especially Northern Scots)

• /vr-/ in write, wrought/wrocht (especially Northern Scots); Island Scots: /xr-/

• the convergence of /

θ/ and /t/ to /t/ and of /ð/ and /d/ to /d/ in Island Scots (the

Shetlands)

•/u

/ in house, out, now; Southern Scots: /u/ in word-final position (see GVS above)

• /ø/ or /y/ in moon, good, stool; Northern Scots: /i

/

•/e

/ in home, go, bone; Northern Scots: /i/

• /hw-/ in what, when etc.; Northern Scots: /f-/

In Urban Scots many of the features listed are recessive, for example, /x/, /kn-/, or

/vr-/. However, /hw/ is generally retained; furthermore, Scots remains firmly rhotic. Yet

some younger speakers do merge /w/ and /hw/, and some also delete non-prevocalic /r/.

Glasgow English is a continuum with a variety of forms ranging from Broad (rural) Scots

to SSE. This involves a fair amount of code-switching as the following exchange over-

heard in an Edinburgh tearoom illustrates:

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN THE BRITISH ISLES 237

A: Yaize yer ain spuin.

B: What did ye say?

A: Ah said, Yaize yer ain spoon.

B: Oh, use me own spoon.

(from Aitken 1985: 42)

Often pronunciations in which only certain lexical items retain a more traditional Scots

pronunciation are found with only selected words while other words have an SSE real-

ization. For example, the vowel /

/ is found in the items bloody, does and used; /i/ in

bread, dead and head; /u/ in about, around, brown, cow, etc; and /e/ in do, home, no

etc.

Glasgow speakers have lost much of the traditional vocabulary of Scots; in its place,

so to speak, they have available an extensive slang vocabulary of varying provenience,

but it does include such Scots expressions as plunk ‘to play truant’ or local Glasgow heid-

banger ‘lunatic’ (Macafee 1983: 43). Grammatical features of Glasgow English which

differ from StE are a mixture of Scots forms such as verb negation using enclitic -nae or

-ny (e.g. isnae ‘isn’t’) and general non-standard forms which can be found throughout

the English speaking world (e.g. multiple negation, as in canny leave nuthin alane, ‘cannot

leave anything alone’).

10.2.3 Scottish Standard English (SSE)

StE in Scotland is virtually identical to StE anywhere else in the world. As elsewhere,

SSE has its special national items of vocabulary. These may be general, such as

outwith ‘outside’, pinkie ‘little finger’, or doubt ‘think, suspect’; they may be culturally

specific, such as caber ‘a long and heavy wooden pole thrown in competitive sports, as

at the Highland Games’ or haggis ‘sheep entrails prepared as a dish’; or they may be

institutional, as with sheriff substitute ‘acting sheriff’ or landward ‘rural’.

Syntactically, SSE shows only minor distinctions vis-à-vis other types of StE. For

instance, in colloquial usage, the modal verb system differs inasmuch as shall and ought

are not present, must is marginal for obligation and may is rare (Miller and Brown 1982:

7–11).

SSE has its own distinct pronunciation as is the case with all national or regional

varieties of English. Some of its features are similar to those of Scots: It maintains /x/,

spelled <ch>, in some words such as loch or technical. /hw/ and /w/ are distinct as in

wheel and weal. /l/ is dark [

] in all environments for most speakers though it is clear

everywhere for some speakers in areas where Gaelic is spoken or was earlier; it is also

clear in the southwest (Dumfries and Galloway) (Wells 1982: 411f.). This variation in

the pronunciation of /l/ is rooted in the fact that SSE includes two very different tradi-

tions. One of these is the Lowlands Scots background, discussed above. The other tradition

is that of Gaelic as a substratum. This means that the phonetic habits of Gaelic are carried

over to English. The more immediate the influence of Gaelic, the more instances there

will be of English influenced phonetically by Gaelic.

Outsiders are often struck by the fact that the glottal stop [

ʔ] is widespread for medial

and final /t/ in the central Lowlands, including Glasgow and Edinburgh. In Glasgow its

use has been shown to vary with age, sex and social class, being more frequent among

238 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

the young, among males and in the working class (Macaulay 1977: 48). This is, there-

fore, arguably not a feature of speakers of SSE.

SSE is a rhotic accent, pronouncing /r/ wherever it is written. The articulation of the

/r/ is sometimes rolled or trilled [r], sometimes flapped [

ɾ], sometimes constricted [ɹ];

however, some speakers even have non-rhotic realizations. Whatever the case, SSE differs

considerably from other rhotic accents because it preserves the /e/–/

/–// distinction

before /r/ in words like heard–bird–word, where in RP and GenAm these vowels have

all merged to central /

/. Note, however, that there are a number of local differences

within Scotland. Moreover, Scottish English also distinguishes between /o/ and /

ɔ/ before

/r/ as in hoarse and horse.

The vowel system of SSE does not, on the other hand, maintain all the vowel contrasts

of RP. Where the latter has /u

/ in fool and /υ/ in full, SSE has undifferentiated /u/ in both

and often central [

%] or even fronted [y]. Not quite as widespread is the loss of the contrast

between /

ɒ/ and /ɔ/ (not vs nought) and the opposition between // and /a/ (as in

cat and cart) are missing as well, though even less frequently. It has been suggested

that these three stand in an implicational relationship, which means that whoever

neutralizes /

/–/a/ also neutralizes the other two pairs. And whoever loses the opposi-

tion between /

ɒ/ and /ɔ/ also loses that between /υ/ and /u/, but not necessarily the

/

/–/a/ one.

Scottish English does not rely on vowel length differences as both RP and GenAm

do. Length does not seem to be phonemic anywhere. However, there are interesting

phonetic differences in length which have been formulated as Aitken’s Law. According

to this all the vowels except /

/ and // are long in morphemically final position (for

example, at the end of a root such as brew, but also at the end of bimorphemic brew +

ed). Vowels are also longer when followed by voiced fricatives, /v,

ð, z/ and /r/. Because

of this, brewed contrasts phonetically with brood, which has a shortened vowel (Wells

1982: 400f.). Closely related to this are the differing qualities of the vowels in tied and

tide. The former is bimorphemic tie + ed with /ae/. Tide is a single morpheme in which

the vowel is not followed by one of the consonants which causes lengthening; it has the

vowel /

/ (see Aitken 1984: 94–100).

10.3 IRELAND

Ireland is divided both politically and linguistically and, interestingly enough, the

linguistic and the political borders lie close together. Northern Ireland (the six counties

of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone), with a population of

approximately 1.5 million, is politically a part of the United Kingdom while the remaining

26 counties form the Republic of Ireland (population of about 3.5 million). Although Irish

English (IrE), which is sometimes called Hiberno-English, shares a number of charac-

teristics throughout the island, there are also a number of very noticeable differences (see

10.3.2 and 10.3.4). Most of these stem from fairly clear historical causes. The northern

counties are characterized by the presence of Scots forms. These originated in the large

scale settlement of the north by people from the Scottish Lowlands and the simultaneous

displacement of many of the native Irish following Cromwell’s subjection of the island

in the middle of the seventeenth century. In what is now the Republic, a massive change

from the Irish language (a Celtic language related to Welsh and Scottish Gaelic) began

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN THE BRITISH ISLES 239

around the year 1800. The type of English which became established there stems from

England and not Scotland and shows some signs of earlier settlement in the southeast by

people from the west midlands of England. Most characteristic of southern IrE, however,

are the numerous features in it which reflect the influence of Irish as the substratum

language. In a few areas in the west called Gaeltacht, Irish is still spoken; and Irish is

the Republic’s official language (together with English, the second official language).

The percentage of population who actually speak Irish is, however, very low (around two

per cent).

10.3.1 Northern Ireland

The split in Ireland as a whole is reflected once again within the historical province of

Ulster, which is partly in the Republic (the three counties of Cavan, Donegal and

Monaghan) and partly in Northern Ireland. The population of Northern Ireland itself is

divided very much along confessional lines, somewhat under one half Roman Catholic

(the Republic is over 90 per cent Catholic) and the remainder chiefly Protestant. This,

too, reflects the historical movement of people to and within Ireland. The northern and

eastern parts of the province are heavily Scots and Protestant; the variety of English

spoken there is usually referred to as Ulster Scots or, sometimes, Scotch-Irish. Further to

the south and west the form of English is called Mid-Ulster English, and its features

increasingly resemble those of English in the South, with South Ulster English as a tran-

sitional accent.

The same split, but also new, mixed or compromise forms, can be observed in Belfast,

which at approximately half a million is the largest city in Northern Ireland and second

only to Dublin in all of Ireland. Although there is a great and ever growing amount of

sectarian residential patterning, speech forms in the city as a whole are said to be merging

(Barry 1984: 120). Harris, for example, states: ‘The vowel phonology of Mid Ulster

English can be viewed as an accommodation of both Ulster Scots and south Ulster English

systems’ (1984: 125). Phonetically, however, there are distinct Ulster Scots and South

Ulster English allophones in Belfast. One of the most potent reasons advanced for the

increasing levelling of speech forms is the weakening of complex (‘multiplex’) social

networks (with shared family, friends, workmates, leisure time activities). Especially

in the middle class, where there is more geographical mobility, and in those parts of

the working class where unemployment has weakened social contacts (in the non-

existent workplace), there is a move away from complex local norms and distinctions,

one of which is shared language norms (see Milroy 1991: 83f.). The practical conse-

quence of the interplay of socio-economic patterns, regional origin and social networks

of varying complexity in Belfast is a zigzag pattern of linguistic variants representing

reality in which there is no unambiguous agreement on prestige models of speech (whether

overt or covert). Furthermore, political affiliations (pro-British unionists vs Republican

nationalists), especially where residence patterns, schooling and workplace are so highly

segregated, help to reinforce this diversity of norms (Harris 1991: 46).

240 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

10.3.2 Characteristics of English in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has a number of distinct speech areas (see Map 10.2). In the north and

the east there is a band of Scots speech areas running from County Down through Antrim

and Londonderry to Donegal. Its linguistic features are similar to those described in 10.2.2,

including Aitken’s Law. Notably different is the lack of dark [

] (see Harris 1985: 18–33).

Generally to the south of these areas comes Mid-Ulster English, which is also the variety

spoken in Belfast. In the very south of Ulster there is what has been called South Ulster

English, a ‘transitional dialect’ (Harris 1984: 118) between Ulster English and Ulster

Scots and southern Hiberno-English (see 10.3.4). The differences between these varieties

are especially noticeable in their vowel phonologies. Harris (1985: 10) also emphasizes

that the phonetic conditioning of vowel length in the Scots varieties as opposed to the

phonemic length of the English varieties is mixed in Mid-Ulster English and Belfast

Vernacular, ‘the dialect upon which the regional standard pronunciation is based’ (ibid.:

15). Belfast has also introduced some innovations, for example, more instances of dark

[

], the loss of the /w/–/hw/ distinction and some glottalization of voiceless stops before

sonorants (bottle [ba

ʔt

]. Ulster Scots has considerably more glottaling. Belfast also has

local forms for mother, brother etc. without the medial /

ʔ/ as in [brɔ

¨

ər]. Among the

specifically northern grammatical forms the best known is probably the use of the second

person plural pronoun youse. For other points see Harris 1984: 131–3.

10.3.3 Southern Ireland

In general, it seems that Southern Irish English has more features in common region-

ally than it does differences; nevertheless, a speaker’s origin is usually localizable.

Social distinctions are, in contrast, much clearer. At the top of the social pyramid there

is an educated variety, sometimes termed the ‘Ascendancy accent’, which is relatively

close to RP. However, this accent does not serve as a norm. Indeed, if there is a standard

of pronunciation, it is likely to be based on that of Dublin. English in Dublin is, of course,

far from uniform. Bertz recognizes three levels: Educated, which is reserved for more

formal styles and used by people with academic training; General, which is found over

a wide range of styles and is used by the more highly trained (journalists, civil servants

etc.); and finally, Popular, which is again stylistically more restricted, namely, to informal

levels and which is typically heard among speakers with a more limited, elementary

education.

Further distinctions in IrE are those which run along urban–rural lines. Filppula (1991)

found that three typically IrE constructions (clefting, topicalization and the use of the

subordinate clause conjunction and; see 10.3.4) were significantly more frequent among

rural than among Dublin speakers. The explanations offered are: urban speakers are

further from the Irish substratum; there were lower frequencies in rural Wicklow, which

has long been English speaking, than in Kerry and Clare, where change has been more

recent; furthermore, Dubliners have more contacts with the non-Irish English speaking

outside world.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN THE BRITISH ISLES 241