Gramley, Stephan; P?tzold, Kurt-Michael. A Survey of Modern English

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Canadian about Canadian English is not its unique features (of which there are a handful)

but its combination of tendencies that are uniquely distributed’ (Bailey 1984: 161). Not

the least of the factors contributing to the independence of CanE are the attitudes of anglo-

phone Canadians, which strongly support a separate linguistic identity.

The effect of attitudes on language behaviour is revealed in a study in which Canadians

with relatively more positive views of the United States and of Americans are also

more likely to have syllable reduction in words like the following: mirror (= mere),

warren (= warn), or lion (= line). They also have fewer high diphthongs in words such

as about or like (see below) and are more likely to voice the /t/ in words like party, butter

or sister. Finally, they use more American morphological and lexical forms. Pro-British

attitudes correlate well with a preservation of vowel distinctions before an /r/, such as

spear it vs spirit, Mary vs merry vs marry, furry vs hurry and oral vs aural as well as

distinct vowels in cot vs caught. Pro-Canadian attitudes mean relatively more levelling

of the vowel distinctions just mentioned, more loss of /j/ in words like tune, dew, or new

(also true of speakers with positive attitudes towards the United States). Canadianisms

are heard more among such speakers as well. A number of surveys have been conducted

to register preferences with regard to the pronunciation of various individual words

(tomato with /e

/ or /ɑ/, either with /i/ or /a/, lever with /e/ or /i/ etc.) as well as

spellings. Approximately 75 per cent say zed (BrE) instead of zee (AmE) as the name of

the letter and just as many use chesterfield (specifically CanE) for sofa (AmE and BrE).

Two thirds have an /l/ in almond (GenAm), but two thirds also say bath (BrE) the baby

rather than bathe (AmE) it (Bailey 1984: 160). BrE spellings are strongly favoured in

Ontario; AmE ones in Alberta. Indeed, spelling may call forth relatively emotional reac-

tions since it is a part of the language system which (like vocabulary use) people are

especially conscious of, in contrast to many points of pronunciation. This means that using

a BrE spelling rather than an AmE one can, on occasion, be something of a declaration

of allegiance. As the preceding examples indicate, differences between CanE and US

AmE are, aside from the rather superficial spelling distinctions, largely in the area of

pronunciation and vocabulary. Grammar differences are virtually non-existent, at least

on the level of StE.

Vocabulary provides for a considerable number of Canadianisms. As with many vari-

eties of English outside the British Isles, designations for aspects of the topography and

for flora and fauna make up many of these items. Examples are: sault ‘waterfall’, muskeg

‘a northern bog’, canals ‘fjords’ (topography), cat spruce ‘a kind of tree’, tamarack ‘a

kind of larch’, kinnikinnick ‘plants used in a mixture of dried leaves, bark and tobacco

for smoking in earlier times’ (flora); and kokanee ‘a kind of salmon’, siwash duck ‘a kind

of duck’ (fauna). The use of the discourse marker eh? is also considered to be especially

Canadian (on discourse markers, see 7.5.2), for example:

I’m walking down the street, eh? (Like this, see?) I had a few beers, en I was feeling

priddy good, eh? (You know how it is.) When all of a sudden I saw this big guy,

eh? (Ya see.) He musta weighed all of 220 pounds, eh? (Believe me.) I could see

him from a long ways off en he was a real big guy, eh? (I’m not fooling.) I’m minding

my own business, eh? (You can bet I was.)

(McCrum et al. 1992: 264)

252 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Many words peculiar to Canada are, of course, no different in status than the regional

vocabulary peculiar to one or another region of the United States, and much of the

vocabulary that is not part of BrE is shared with AmE in general.

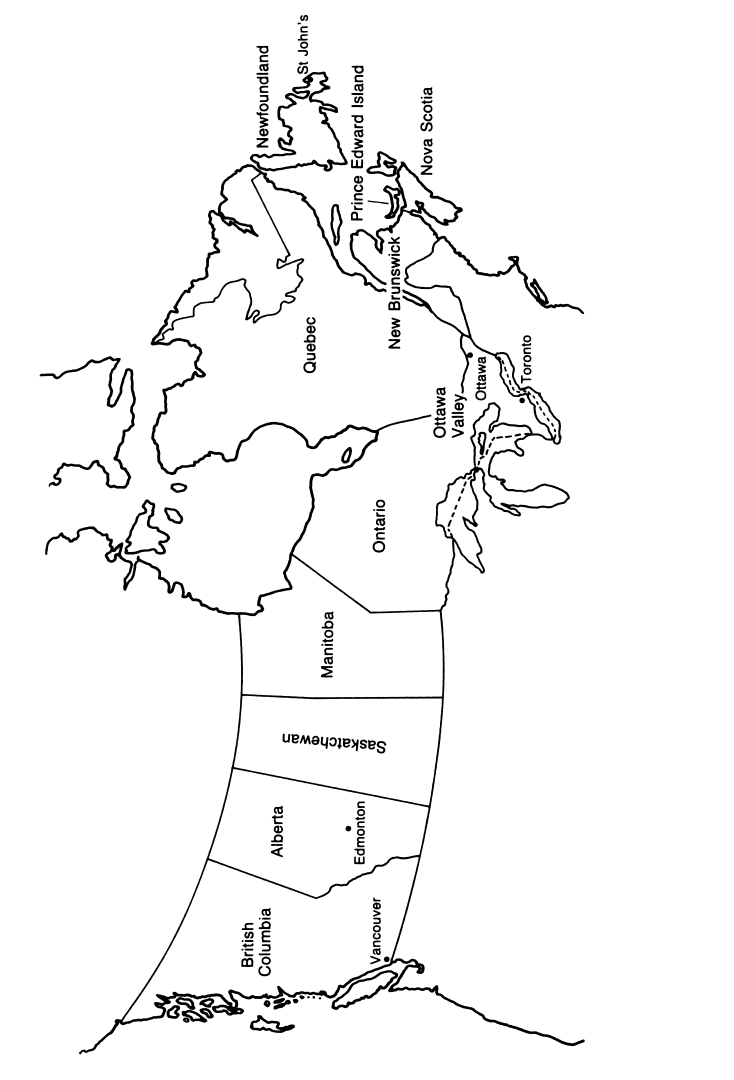

The pronunciation of CanE (sometimes called General Canadian) applies to Canada

from the Ottawa Valley (just west of the Quebec–Ontario border) to British Columbia

and is similar to what has been described as GenAm (see Chapters 4 and 12). It shares

the same consonant system, including the unstable contrast between the /hw/ of which

and the /w/ of witch. Its vowel system is similar to that of the northern variety of GenAm,

which means that the opposition between /

ɑ/ and /ɔ/ as in cot and caught has been lost

(except by the Anglophiles mentioned above). The actual quality of the neutralized vowel

is said to vary according to the phonetic environment, for example [

ɔ] (exclusively) as a

possible regional realization in Edmonton. The distinctions between /i

/ and // (the

stressed vowel of beery vs that of mirror), between /e

/, /e/ and // (Mary vs merry vs

marry) and between /

ɒ/ and /ɔ/ (oral vs aural) are rapidly dying out in CanE as they are

in most varieties of AmE.

What shows up as the most typical Canadian feature of pronunciation is what is gener-

ally called ‘Canadian raising’. This refers to the realization of /

ɑυ/ and /a/ with a higher

and non-fronted first element [

u] and [i] when followed by a voiceless consonant.

Elsewhere the realization is [au] and [a

]. Hence each of the pairs bout [but] – bowed

[baud] and bite [b

it] – bide [bad] have noticeably different allophones. While other vari-

eties of English also have such realizations (e.g. Scotland, Northern Ireland, Tidewater

Virginia), the phonetic environment described here is specifically Canadian. One of the

most interesting aspects of Canadian raising is its increasing loss (levelling to /

ɑυ/ and

/a

/ in all phonetic environments) among young Canadians. This movement may be under-

stood as part of a standardization process in which the tacit standard is GenAm and not

General CanE. This movement has been documented most strongly among young females

in Vancouver and Toronto and is indicative of a generally positive attitude towards things

American, including vocabulary choice. However, an independent development among

young Vancouver males, namely rounding of the first element of /

ɑυ/ before voiceless

consonants as [ou], is working against this standardization and may be part of a process

promoting a covert, non-standard local norm (Chambers and Hardwick 1986).

Regional variation in CanE The emphasis in the preceding section was on the

English westwards of the Ottawa Valley (sometimes called Central/Prairie CanE even

though it reaches to the Pacific). It is an unusually uniform variety, at least as long as the

focus is on urban, middle class usage – and Canada is overwhelmingly middle class and

urban – and the bulk of the English speaking population lives in the area referred to.

Working class usage is said to differ not only from middle class CanE, but also in itself

as one moves from urban centre to urban centre. Woods shows working class preferences

in Ottawa to be more strongly in the direction of GenAm than middle and upper class

preferences are, at least in regard to the voicing of intervocalic /t/ and the loss of /j/ in

tune, new and due words. Working class speech patterns also favour /

n/ over /ŋ/ for the

ending {-ing} and tend to level the /hw/–/w/ opposition more completely (1991: 137–43).

Eastwards from the Ottawa Valley and including the Maritime provinces of New

Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island is the second major region of CanE.

Here the norms of pronunciation are varied. For the Ottawa Valley alone Pringle and

Padolsky distinguish ten distinct English language areas. Much of the variation they

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 253

Map 11.1 Canada

recognize may be accounted for by the settlement history of the Valley: Scots, northern

and southern Irish, Kashubian Poles, Germans and Americans (especially Loyalists who

left the United States during and after the War of Independence) (Pringle and Padolsky

1983: 326–9). Although there is also much variation in the Maritime areas as well, the

Eastern Canadian region is perhaps best characterized overall as resembling the English

of New England, which is where many of the earliest settlers came from; there is, for

example, less /

ɑ/–/ɔ/ levelling, yet the English of this area is, like all of Canada, rhotic

(/r/ is pronounced where spelled), while Eastern New England is non-rhotic.

The final distinct region of CanE is Newfoundland (population approximately

570,000). Wells even speaks of the existence of traditional dialects in Newfoundland,

something which exists in the English speaking world only in Great Britain and Ireland

and perhaps in the Appalachian region of the United States. The linguistic identity of

Newfoundland is the result of early (from 1583 onwards) and diverse (especially Irish

and southwest English) settlement, stability of population (93 per cent native born)

and isolation. Since it joined Canada in 1949 its isolation has been somewhat less and

the influence of mainland pronunciation patterns has become stronger. Yet the distinct

phonological identity of Newfoundland English is well rooted. Southwestern English

influences have been observed in the voicing of initial /f/ and /s/. IrE influences include

clear [l] in all environments; also monophthongal /e/ (for /e

/) and /o/ (for /əυ/ or /oυ/);

/

/ is rounded and retracted. Some speakers neutralize /a/ vs /ɔ/, realizing both as /a/.

The dental fricatives /

θ/ and /ð/ are most often /t/ and /d/ (but also dental [t] and [d]).

Furthermore, pate /p

εt/ and bait /bεt/ do not traditionally rhyme; /h/ is generally

missing except in standard speech; and consonant clusters are regularly simplified, e.g.

Newfoun’lan’ or in pos’ (= ‘post’) (see Wells 1982: 498–501). ‘Canadian raising’ is

universal in all phonetic environments for some speakers (Chambers 1986: 13).

Many of these features are typical only of older Newfoundlanders, ‘while the speech

patterns of certain teenage groups would be, to the untrained observer at least, virtually

indistinguishable from those of teenagers in such major Canadian centres as Toronto or

Vancouver’ (Clarke 1991: 111). In other words, considerable change is taking place in

Newfoundland English, and ‘age is by far the most important’ (ibid.: 113) of the socio-

linguistic factors involved, with females generally taking the lead. In contrast, ‘loyalty to

the vernacular norm is most evident among older speakers, males, and lower social strata’

(ibid.: 116).

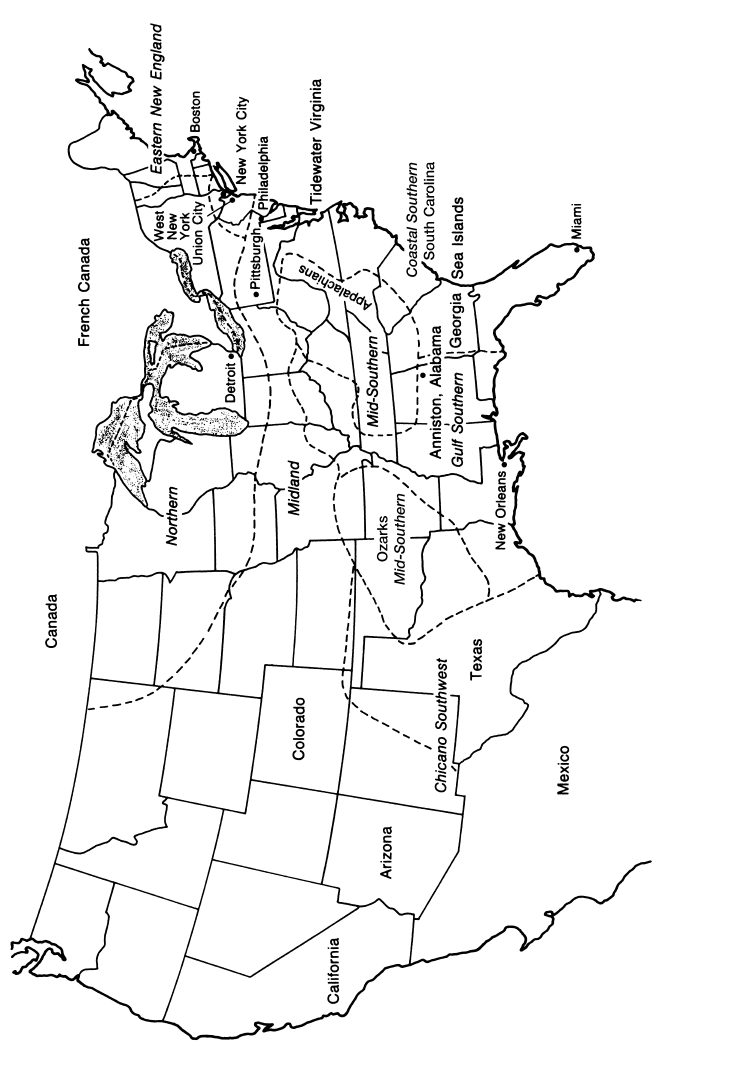

11.2.2 The United States

The regional varieties of English in the United States consist of three general areas (see

Map 11.2): Northern, of which CanE is a part, Midland and Southern. Each of these may

be further differentiated into subregions. Grammar is of relatively little importance for

these three areas; most of the dividing and subdividing is based on vocabulary and

pronunciation, though the two may not lead to identical areas. However, the lexical

distinctions are themselves most evident in the more old-fashioned, rural vocabulary

which is investigated in the various dialect geographical projects in or related to the

‘Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada’: The earliest to be carried out was the

Linguistic Atlas of New England (LANE; Kurath et al. 1939–43), which was followed by

numerous other regional Linguistic Atlas studies. Increasingly, general North American

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 255

terms are replacing such distinctions as Northern (devil’s) darning needle, or Midland

snake doctor/snake feeder or Southern mosquito hawk ‘dragon fly’. However, some urban

terms continue to reinforce the older regional distinctions. For example, hero (New York),

sub/submarine (Pittsburgh), hoagie (Philadelphia), grinder (Boston), po’ boy (New

Orleans) and a number of others all designate a roughly similar, over-large sandwich made

of a split loaf or bun of bread and filled with varying (regional) goodies. Each of the

cities just mentioned is, more or less coincidentally, also the centre of a subregion. On

the whole, vocabulary offers distinctions which are often infrequent and which can usually

easily be replaced by more widely accepted terms.

Pronunciation differences, in contrast to lexis, are evident in everything a person says

and less subject to conscious control. The Southern accents realize /a

/ as [a

] or [a], that

is, with a weakened off-glide or no off-glide at all, especially before a voiced consonant,

and /u

/ and /υ/ are being increasingly fronted. Lack of rhoticity is typical of Eastern New

England and New York City, but not the Inland North. It is also characteristic of Coastal

Southern and Gulf Southern, even though younger white speakers are increasingly rhotic,

while Mid Southern (also known as South Midland) has always been rhotic. Northern

does not have /j/ in words like due or new, nor does North Midland, but /j/ may occur

throughout the South. The /

ɑ/–/ɔ/ opposition is maintained in the South (with tenden-

cies towards its loss in parts of Texas), but has been lost in the North Midland and is

weakening in the North. ‘Canadian raising’ is a Northern form which, despite its name,

is common in many American cities of the Inland North (see 11.2.1).

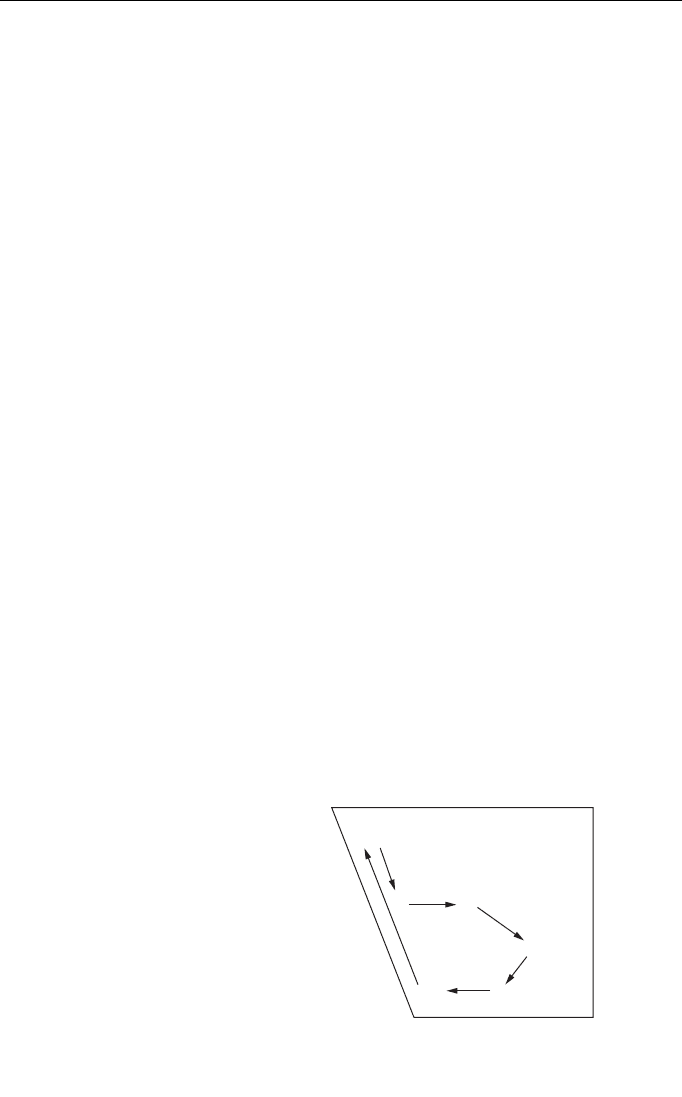

The Northern Cities Shift is a demonstration of changes within AmE pronunciation.

It is taking place in the northern dialect area of the United States (including Detroit,

Chicago, Cleveland, Buffalo) and affects the short vowels. As the diagram shows, this

involves a chain-like movement in which realization of each of the phonemes indicated

changes, but the distinctions within the system are maintained (see 10.2.2, 10.4.1 and

13.1.1 for further chain shifts).

The pronunciation of the Northern Midland area more or less from Ohio westwards,

has often been referred to as General American (GenAm). This label is a convenient

fiction used to designate a huge area in which there are numerous local differences in

pronunciation, but in which there are none of the more noticeable subregional divisions

such as those along the eastern seaboard. Furthermore, the differences between North

Midland and Inland North are relatively insignificant. Both areas are rhotic, are not likely

256 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

Ann → Ian // → //

bit → bet // → /ε/

bet → bat / but /ε/ → //

lunch → launch // → /ɔ/

talk → tuck /ɔ/ → /ɑ/

locks → lax /ɑ/ → //

ɑ

ɔ

ε

Figure 11.1 The Northern Cities Chain Shift

to vocalize /l/, have /a/ as [] or [a], do not distinguish /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ (or increasingly

do not; note, however, that this opposition is still recognized in this book) and no longer

maintain the /j/ on-glide in the due words. Most significant of all for the selection of

North Midland for the label GenAm is the fact that it is this type of accent more than

any other which is used on the national broadcasting networks.

The most noticeable regional contrast is that between North and South. This division

is, in addition to vocabulary and pronunciation differences, underscored to some extent

at least by grammatical features. It seems that it is only in Southern varieties, including

Black English Vernacular (or African American Vernacular English; see 11.4.3), that such

admittedly non-standard features occur as perfective done (e.g. I done seen it), future gon

(I’m gon [not goin’] tell you something) and several more far reaching types of multiple

negation, such as a carry-over of negation across clauses (He’s not comin’, I don’t believe

= ‘I believe he’s not coming’).

It is also in the South that an area is to be found with speech forms approaching the

character of a traditional dialect (such as otherwise found only in Great Britain and Ireland,

and possibly also in Newfoundland). The dialect which is meant is Appalachian English

and the related Ozark English, which are found in the Southern Highlands (Mid Southern

on Map 11.2). The English of these regions is characterized by a relatively high incidence

of older forms which have generally passed out of other forms of AmE. Examples include

syntactic phenomena such as a-prefixing on verbs (I’m a-fixin’ to carry her to town),

morphological-phonological ones such as initial /h/ in hit ‘it’ and hain’t ‘ain’t’ and lexical

ones such as afore ‘before’ or nary ‘not any’.

11.3 SOCIAL VARIATION IN A

M

E

Besides differences according to the gender of the speaker (see Chapter 9) and race or

ethnicity (see 11.4), there are significant differences according to the socially and econom-

ically relevant factors of education and social class. In North America socio-economic

status shows up in pronunciation inasmuch as middle class speakers are on the whole

more likely than those of the working class to adopt forms which are in agreement with

the overt norms of the society. The now classic investigations of Labov in New York

City in the 1960s provided a first insight into these relations (Labov 1972a). This may

be illustrated by the finding that initial voiceless <th-> (as in thing) is realized progres-

sively more often as a stop [t] or an affricate [t

θ] than as a fricative [θ] as the classification

of the speaker changes from upper middle to lower middle, to working to lower class

(Labov 1972b: 188–90).

Although variation is usually within a range of regional or local variants, it may in

some cases be a non-regional standard which is aimed at. For example, New Yorkers

increasingly (with middle class women as leaders) pronounce non-prevocalic <r>

even though rhoticity was not traditionally a feature of New York City pronunciation.

Since younger speakers also favour pronunciation of this <r>, this is not only an excel-

lent example of the differing speech habits of differing social classes and the greater

orientation of women towards the overt norm, but also the gradual adoption of rhoticity

by a new generation, a fact that indicates a probable long-term change in the regional

standard.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 257

Map 11.2 The United States

Social distinctions are especially perceptible in the area of grammar, where a remark-

able number of stigmatized features (often referred to as shibboleths) apply supra-

regionally. All of these features are within the scope of GenE. Nevertheless, a person is

regarded as uneducated, unsophisticated and uncouth who uses

1 ain’t (e.g. I ain’t done it yet)

2 a double modal (I might could help you)

3 multiple negation (We don’t need none)

4 them as a demonstrative (Hand me them cups)

5 no subject relative pronoun in a defining relative clause (The fellow wrote that letter

is here)

6 don’t in the third person singular (She don’t like it)

7 was with a plural subject (We was there too early)

8 come, done, seen, knowed, drownded etc. for the simple past tense

9 took, went, tore, fell, wrote etc. as a past participle.

Investigations of usage have revealed that these and other non-standard forms are used

most by the less well educated of the rural and urban working class (e.g. Feagin 1979).

Users are also frequently the oldest and most poorly educated rural speakers such as were

often sought out for studies in the framework of the Linguistic Atlas studies. It would be

a mistake, however, for the impression to arise that such non-standard forms are somehow

strange or unusual merely because StE, and therefore the written language, does not

include them. The contrary is the case. All of them are very common. Indeed, many of

them may be majority forms. In Anniston, Alabama, for example, third person singular

don’t was found to be used by all the working class groups investigated more than 90

per cent of the time, except for urban adult males, whose rate was 69 per cent. The use

of singular don’t by the Anniston upper class, in contrast, ranged from 0 to 10 per cent

(Feagin 1979: 208). This type of situation seems to be the case wherever English is

spoken.

11.4 ETHNIC VARIETIES OF A

M

E

As might be expected in countries of immigration, in the immigrant generation and some-

times in the second generation many people speak an English which is characterized by

first language interference. Experience has shown, however, that by the fourth generation

most of the descendants of immigrants have become monolingual English speakers

(Valdés 1988: 115f.), and virtually all signs of interference have vanished. There are then

no grounds for speaking of an ethnic variety. Recognizing such a variety would be justi-

fied only if it could be viewed as distinct from mainstream AmE and as self-perpetuating.

Yet there are some groups of native English speakers in North America who: (a) have

an ethnic identity; and (b) speak a type of English which is distinct in various ways from

the speech of their neighbours of comparable age, class, sex and region. For two of these

groups it is uncertain whether it is really suitable to speak of ethnic rather than inter-

ference varieties of English: Native American Indians and Chicanos. The third group,

African Americans, include a large number who speak the ethnic dialect African American

Vernacular English (see 11.4.3).

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 259

11.4.1 Native American English

Today the majority of American Indians are monolingual speakers of English. For most

of them there is probably no divergence between their English and that of their non-Indian

peers. However, among Native Americans who live in concentrated groups (on reserva-

tions) there are also ‘as many different kinds of American Indian English as there are

American Indian language traditions’ (Leap 1986: 597). This is seen as the result of the

on-going influence of the substratum (the traditional language) on English, even if the

speakers are monolingual. Many of the special features of this English are such familiar

phenomena as word-final consonant cluster simplification (e.g. west > wes’ ), multiple

negation, uninflected (or invariant) be (see below 11.4.3), and lack of subject-verb

concord. Although mainstream non-standard English has the same sort of surface

phenomena, those of American Indian English may be the products of different gram-

matical systems (Toon 1984: 218). It is suggested, for example, that it is because a

traditional language requires identical marking of subject and verb that Indian English

may have such forms as some peoples comes in (ibid.).

11.4.2 Spanish influenced English

Hispanic Americans are one of the two largest ethnic minorities in the United States

(Blacks are the other; each makes up approximately one eighth of the general population

or about 35 million each in 2000). They consist of at least three major groups, Cubans,

Puerto Ricans and Chicanos (or Mexican Americans; but many Central American immi-

grants are grouped with them as well).

Cubans Approximately 600,000 of the roughly 1 million Cuban Americans live in

Dade County/Miami in Florida; another 20 per cent in West New York and Union City,

New Jersey. Because of this areal concentration they have been able to create unified

communities with ethnic boundaries. Nonetheless, integration with the surrounding Anglo

community is relatively great (a high number of inter-ethnic marriages), perhaps because

Cuban Americans, due to the nature of emigration from Cuba, encompass all levels of

education and class membership and are not relegated to an economically marginal posi-

tion vis-à-vis the greater outside society. Only six per cent of the second generation of

Cuban Americans were monolingual Spanish in 1976 (García and Otheguy 1988).

‘Second-generation Cubans, as is usually the case with all second-generation Hispanics,

speak English fluently and with a native North American accent’ (ibid.: 183). Indeed,

perhaps only the presence of loan words and calques/loan translations such as bad grass

(> Span. yerba mala ‘weeds’) may indicate the original provenance of the speakers.

Puerto Ricans Puerto Ricans have, as American citizens, long moved freely between

the mainland United States and Puerto Rico. Most originally went to New York City (see,

for example, West Side Story), and although many have moved to other cities in the mean-

time, approximately 60 per cent of mainland Puerto Ricans are still to be found there,

where they often live in closely integrated ethnic communities. Many members of these

communities are bilingual (only one per cent of second generation mainland Puerto

Ricans are monolingual Spanish speakers; García and Otheguy 1988: 175), and there are

a number of differing Spanish–English constellations of language usage within families.

260 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL VARIETIES OF ENGLISH

One investigation showed that those ‘reared in Puerto Rico speak English marked by

Spanish interference phenomena, while the second generation speaks two kinds of non-

standard English: Puerto Rican English (PRE) and/or black English vernacular (BEV)’

(Zentella 1988: 148).

Chicanos Chicanos make up by far the largest proportion of the Hispanic population

of the United States and are a rapidly growing group. They include recent immigrants as

well as native born Americans who continue to live in their traditional home in the

American Southwest (Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and California), which was

conquered from Mexico and annexed in the middle of the nineteenth century. Chicanos

are most numerous in California, where they are an urban population, and in Texas,

especially southwest Texas, where they are often relatively rural. Spanish is more

commonly maintained in the Texas than in the California environment. Furthermore, large

numbers of Mexican and Central American Hispanics live in urban centres throughout

the United States.

The type of English spoken by many of these people – some bilingual, others mono-

lingual English speakers (5 per cent of second generation Mexican Americans remain

monolingual Spanish speakers; García and Otheguy 1988: 175) – consists of several vari-

eties. Among bilinguals it is characterized by frequent code-switching (sometimes referred

to as Tex-Mex). For many speakers English is a second language and contains numerous

signs of interference from Spanish. However, whether an ‘interference variety’ or a first

language, the linguistic habits of a large portion of the Chicano community are continu-

ally reinforced by direct or indirect contact with Spanish, whose influence is increased

by the social isolation of Chicanos from Anglos. Most important for regarding Chicano

English as an ethnic variety of AmE is that it is passed on from generation to generation

and serves important functions in the Chicano speech community. The maintenance of

Chicano English as a separate variety ‘serves the functions of social solidarity and

supports cohesiveness in the community’ (Toon 1984: 223). It can be a symbol of ethnic

loyalty as when Chicanos use it as one means of Chicano identity vis-à-vis both Mexicans

and Anglos.

The linguistic features of Chicano English are most prominently visible in its

pronunciation, including stress and intonation. There seems to be little syntactic and

lexical deviation from GenE. As with Puerto Ricans, contact with Blacks may result in

the use of various features of Black English among working class Chicanos.

Pronunciation (with obvious signs of Spanish influence):

1 stress shift in compounds (

miniskirt → miniskirt)

2 rising pitch contours (independent of the final fall) to stress lexical items

3 rising pitch in declarative sentences

4 devoicing and hardening of final voiced consonants (please → police)

5 realization of labio-dental fricative /v/ as bilabial stop [b] or bilabial fricative [

β]

6 realization of /

θ/ and /ð/ as [t] and [d] (thank = tank; that = dat)

7 realization of central /

/ as low [a] (one = wan)

8 simplification of final consonant clusters (last = las’)

9 merger of /t

ʃ/ and /ʃ/ to /ʃ/ (check → sheck)

10 merger of /i

/ and // to // (seat = sit) and of /e/ and /e/ to /e/ (gate = get) and occa-

sionally of /u

/ and /υ/ as /υ/ (Luke = look).

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

ENGLISH IN AMERICA 261