Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

362 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

the ninth century. In the politically stable east, in contrast, baths have continued without break

through Byzantine, Arab, and Ottoman Turkish cultures to the present day.

Houses

The many well-preserved private houses rank high among the important finds at Pompeii and

Herculaneum. Built at different times during the Republic and the early Empire, the houses

document developing architectural and decorative styles with a completeness unparalleled in the

Roman world.

The traditional Italic house of the well-to-do features an atrium (pl. atria), probably a legacy of

the Etruscans. Atrium houses are prominent at Pompeii and Herculaneum, as town houses, not

apartments and not free-standing villas surrounded by gardens. They extend right to the street,

with shops lining the street side of many, and they share walls with adjacent houses. Construction

is of rubble and stone faced with concrete, plastered and, on interior surfaces, often decorated.

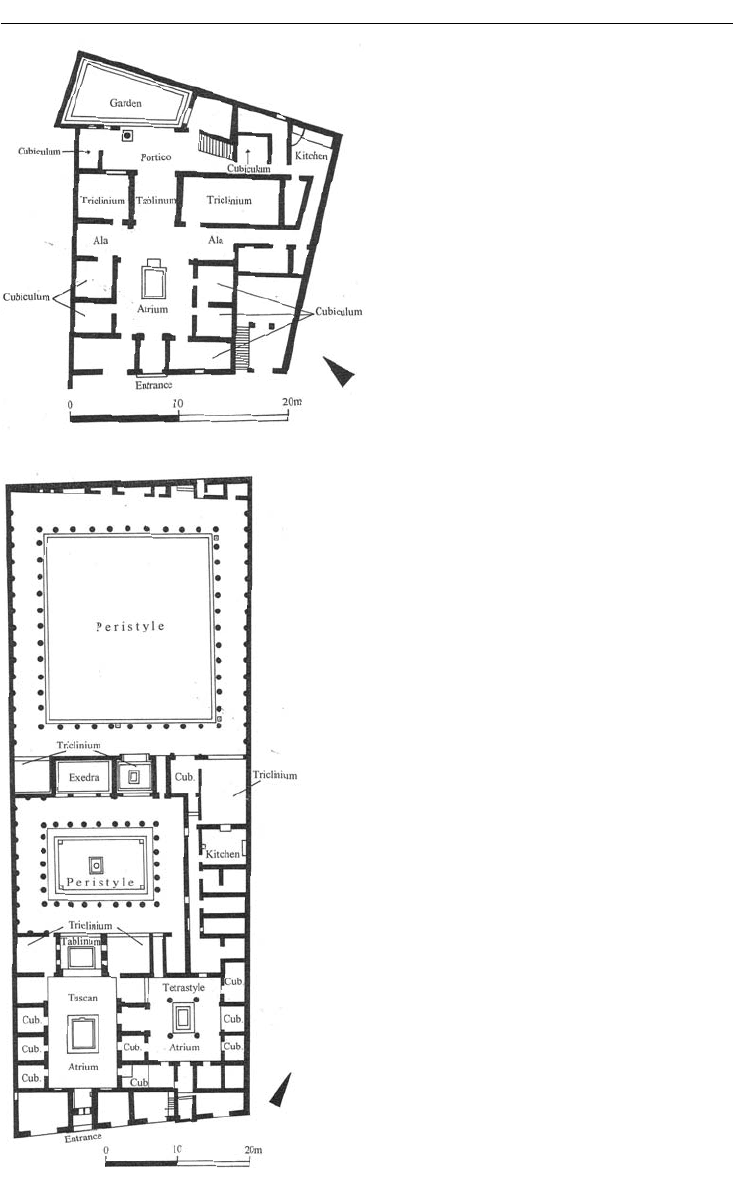

The Roman architect Vitruvius described five different types of atrium houses. Two types

dominate: the Tuscan (the most popular) and the tetrastyle. The House of the Surgeon, originally

of the fourth century BC, one of the earliest surviving houses from Pompeii, has a Tuscan atrium

at its core (Figure 22.5). From the street one passes through an entrance vestibule (fauces) into

the atrium. The room opens to the sky through the compluvium; rain can then fall into a basin

(impluvium) and water tank below. The specifically Tuscan feature of this atrium is the absence of

columns around the basin; the ceiling is supported instead by strong rafters. The compluvium

provides another important service: it lets in light, which otherwise enters only through small slit

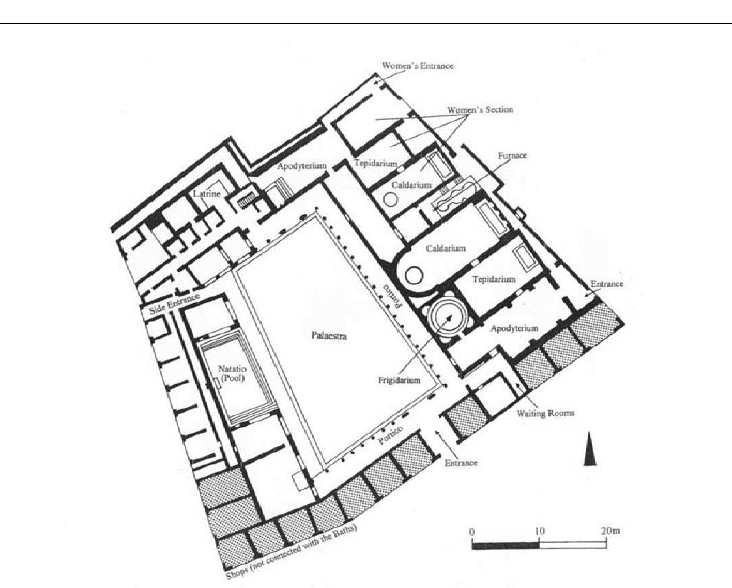

Figure 22.4 Plan, Stabian Baths, Pompeii

POMPEII AND OSTIA 363

windows and the portico at the back, supplemented

by oil lamps and tallow candles. This main room must

have been pleasant in warmer weather, but impos-

sibly chilly in colder seasons. The family would then

retreat with their portable braziers to smaller enclosed

rooms.

Off the atrium lie those smaller rooms, symmetri-

cally arranged for the most part. Furniture tended to

be simple and portable, so the purpose of any particu-

lar room could be quickly changed. The main func-

tions are as follows: small rooms (cubiculum, pl. cubicula)

usable as bedrooms; two wings (alae) in which bust

portraits of ancestors were kept; and, at the rear, the

most important rooms, the dining room (triclinium)

and the main reception room (tablinum). Here, in the

tablinum, the owner and his family formally greeted

guests. A wealthy man would have many “clients,”

people who looked to him for advice, money, and sup-

port, and he received them here.

The House of the Surgeon has a portico and a gar-

den at the back. The unusual trapezoidal shape of the

garden reflects the odd shape of the property. Like-

wise the kitchen occupies a curiously shaped corner;

in such houses, kitchens were small and squeezed in

wherever possible.

Hellenistic Greek influence combines with tradi-

tional Italic in the House of the Faun, built in 185–175

BC but later modified (Figure 22.6). The largest house

Figure 22.5 Plan, House of the Surgeon,

Pompeii

Figure 22.6 Plan, House of the Faun, Pompeil

364 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

in Pompeii, occupying an entire city block, the House of the Faun consists of three parts: public

and private quarters, and peristyle gardens. The public section is the Tuscan atrium, entered

from the street and laid out as in the House of the Surgeon. The private area centers on a tetrastyle

atrium, Vitruvius’s second type, an atrium in which four columns surround the impluvium and

hold up the ceiling.

Behind these public and private atria lie the peristyles, gardens surrounded by a colonnade.

Colonnaded courts enjoyed popularity in the Greek world, but they did not contain gardens. On

Delos, for example, the best Hellenistic houses have colonnaded courts with mosaic floors in

the center. But Delos has no natural water supply, and rainwater had to be collected and used

sparingly. In any case Romans valued and enjoyed gardens. Explorations of the cavities left by

plant roots have allowed researchers to reconstruct the kinds of plants cultivated, and to replant

some gardens as the ancients might have done.

The first peristyle at the House of the Faun was added in ca. 125 BC; a second, larger peristyle

was added in the first century BC. Between them lies a room of a type borrowed from the Greeks,

an exedra, a retreat. The floor of this exedra was decorated with the famous “Alexander Mosaic”

(see Figure 17.13).

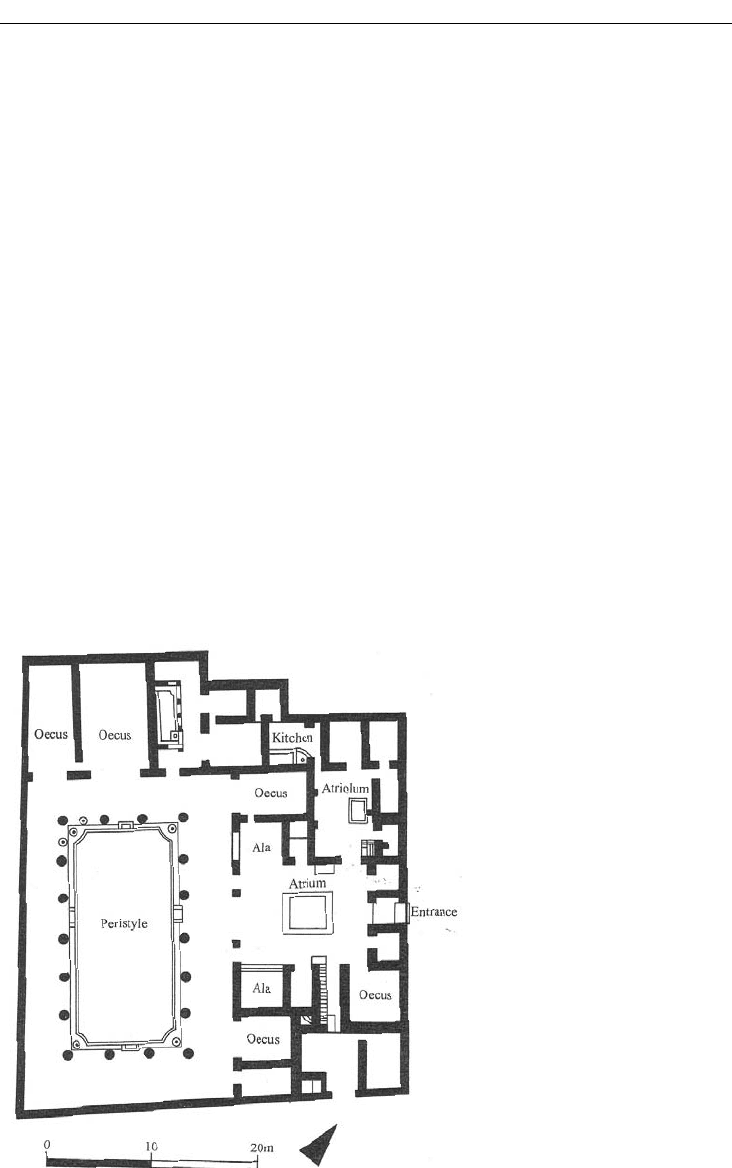

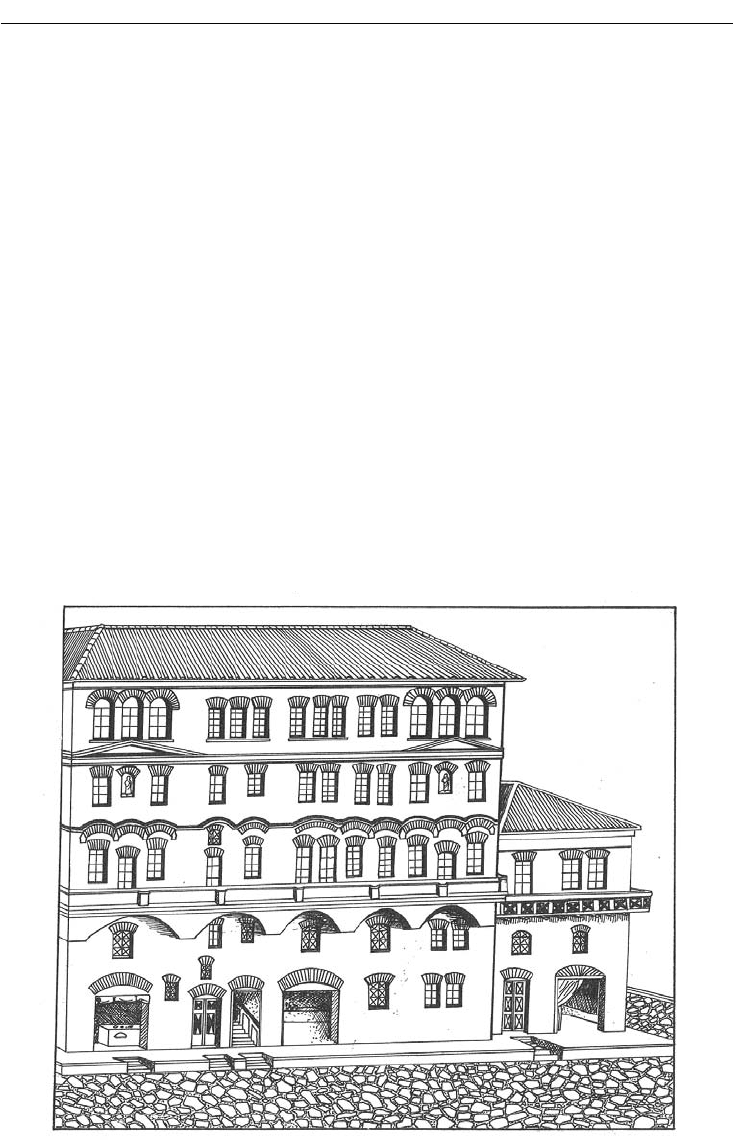

A variant layout occurs in the House of the Vettii, a house remodeled in the late period by two

newly rich freedmen and wine merchants, Aulus Vettius Restitutus and Aulus Vettius Conviva,

and restored in modern times. The plan of the house is compact, but complex (Figure 22.7). The

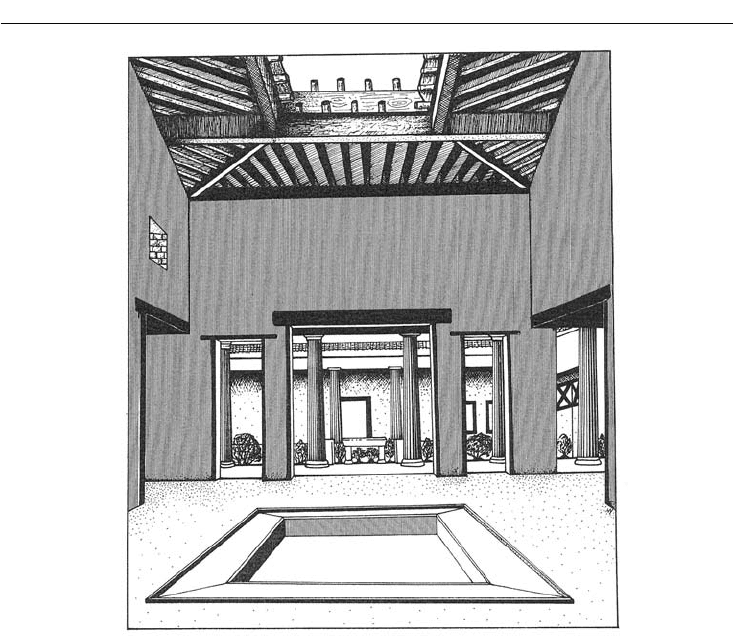

entrance leads into the main atrium, large with a deep impluvium (Figure 22.8). The atrium lacks

a tablinum; instead, one passes directly to the peristyle garden. To the side of the large atrium

lies a small, private atrium supplied with a lararium, a shrine to the lares, the deities who pro-

tected house and family. From here one has access to the kitchen and to the servants’ quarters.

The house has oecae (sing. oecus), dining rooms in the Greek style, large rooms opening onto the

Figure 22.7 Plan, House of the

Vettii, Pompeii

POMPEII AND OSTIA 365

peristyle. These rooms are decorated with the complex architectural scenes characteristic of the

fourth and last style of Pompeiian wall painting.

Wall paintings and the Villa of the Mysteries

The eruption of Vesuvius preserved hundreds of wall paintings in Pompeii and the surrounding

region – the important core of surviving Roman wall paintings. They date of course to the late

Republic and early Empire only; to continue the story of Roman painting after AD 79, one needs

to look elsewhere.

The wall paintings of Pompeii and neighboring towns and indeed of other contemporary

towns (notably Rome) were classified into four groups by German scholar August Mau in 1882.

The types overlap, both chronologically and even in style, but nonetheless remain a useful way

to understand different approaches to the art of decorating walls. The first two styles, at least,

originate in the wall painting tradition of the Greek East, in such places as Delos (First Style) and

Alexandria (Second Style).

The First Style is the easiest to pick out, because it solely depicts well-cut stone masonry.

Figures are absent. This style appears early, beginning in the early second century

BC. The Sec-

ond Style, from ca. 90 BC, introduces architecture and the illusion of three-dimensional space.

Theatrical scenery and the architectural backdrops of stages influenced the development of this

Figure 22.8 Atrium, House of the Vettii, Pompeii

366 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

style. But in a famous variant at the Villa of the Mysteries outside Pompeii, human figures enact

a dramatic cult ceremony in front of only a minimal architectural backdrop.

Villas, in the parlance of Classical archaeology, were large independent houses that stood in

the countryside. Generally the centers of large estates, they combined living quarters with rooms

devoted to farm activities. The Villa of the Mysteries has a complicated building history, unrav-

eled in Italian excavations of 1909–10 and 1929–30. Construction began ca. 200 BC, with a cryp-

toporticus (a high platform with plain arches framing a walkway) and, on top, an atrium. Additions

in the late second century BC included the main peristyle, a small tetrastyle atrium, and baths. A

semi-circular exedra was built on the podium terrace some time in the first century AD. Rooms

now totaled over sixty. In the final years of Pompeii, agricultural installations were added right in

the middle, as if the villa had become strictly a business center. Finds of a winepress, a heap of

onions in the main bedroom, and farm tools (pruning hooks, hammers, picks, hoes, and shovels)

have helped define the character of this villa in its final years.

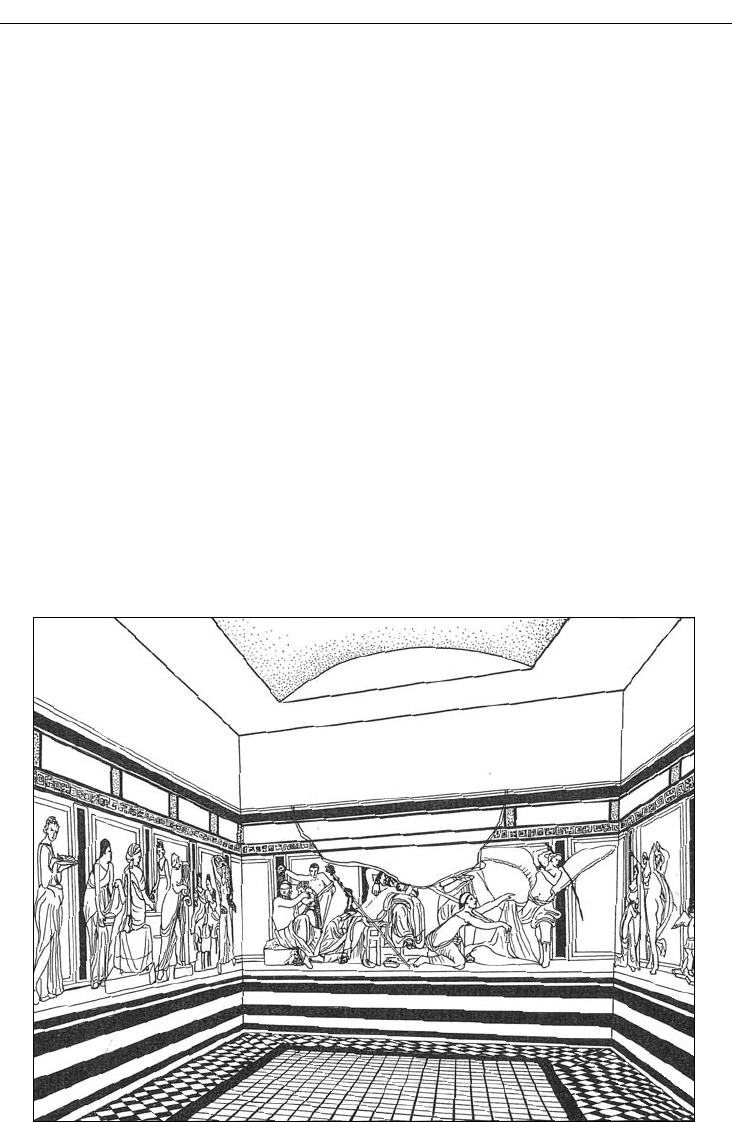

The important paintings of Dionysiac Mysteries, after which the building is named, decorate

the walls of a modestly sized room (7m × 5m) in the heart of the villa (Figure 22.9). They date

to ca. 50 BC. The paintings are 3.3m high, with the figures 1.5m high. In front of a Second Style

background of dark red panels divided by columns, a young woman of unknown identity under-

goes an initiation rite into the Mysteries of the god Dionysos. The scenes unfold in a continuous

narrative, like a comic strip, with figures realistically depicted in the finest Hellenistic–Roman

manner. The story combines the real with the imaginary, for our initiate confronts a variety

of personages, some of whom – satyrs, a winged female brandishing a whip, and Dionysos

(Bacchus) and his consort Ariadne – step directly from Greco-Roman mythology. None of the

Figure 22.9 Mysteries wall paintings, Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii

POMPEII AND OSTIA 367

figures are labeled, and surviving texts say nothing about these scenes. As a result, the precise

meaning of the images and their presence in this country villa remain unexplained.

The Third Style of wall painting, the “ornamental” style, down plays architecture and instead

emphasizes two-dimensional framed spaces, sometimes with small panels inserted in the large

fields as if they were paintings hung separately on the walls. The frames themselves can be highly

decorative. This style appears in Rome during the reign of Augustus and continued in use at

Pompeii until the earthquake of 62. In the final years of the city, the Fourth Style held sway.

This style combines characteristics of the two previous styles, by featuring large paintings of

three-dimensional architecture and figures set inside complex frames. It is this style that has a

prominent place in the House of the Vettii.

OSTIA

While the ruins of Pompeii give us an unparalleled look at a medium-sized Roman town depen-

dent on agriculture, the remains of Ostia, the port of Rome, located at the mouth of the Tiber

River, document a city of commercial importance. Like Pompeii, Ostia gives information about

Roman urbanism that is unavailable from Rome itself. Unlike Rome, Ostia faded after antiquity.

The neglected harbors became swampy and malarial; habitation dwindled. Sand dunes covered

the Roman ruins, an excellent protecting blanket.

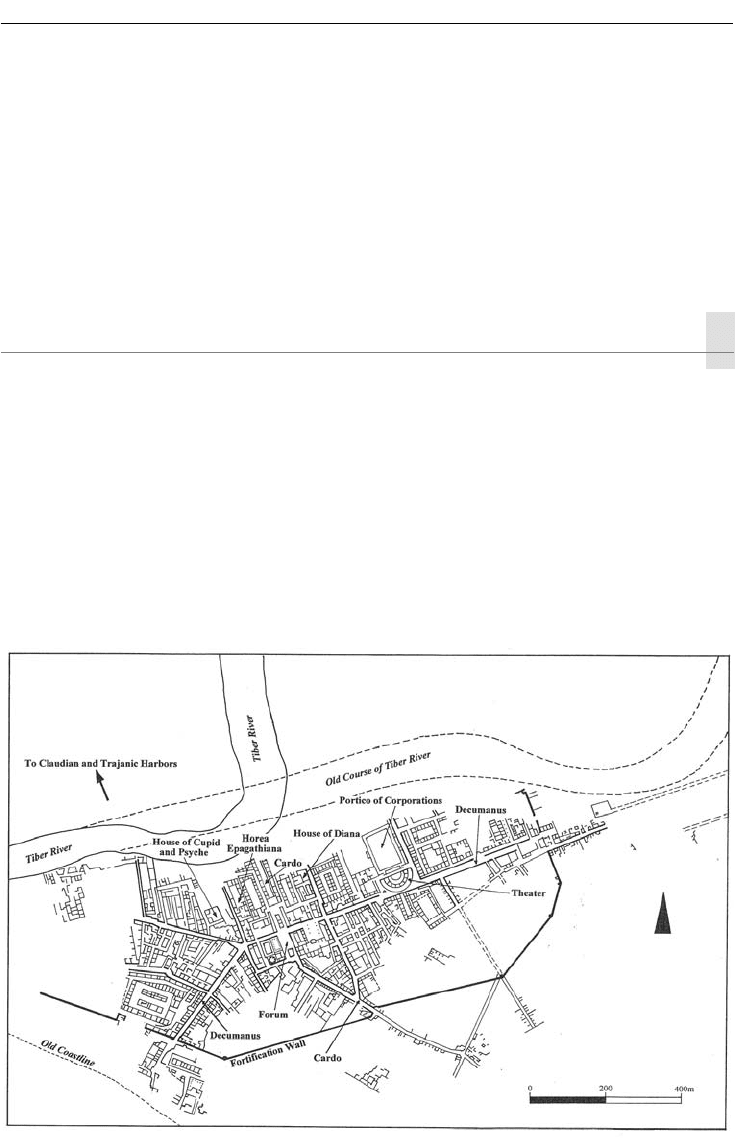

Ostia began ca. 350 BC as a fort (castrum), guarding access to the Tiber River and to Rome

(Chapter 20). Its thick walls enclosed a rectangular area of just over 2ha (Figure 22.10). With two

main streets crossing at right angles and leading to four city gates, this fortified settlement was an

early example of the grid plan in Italy. During the Punic Wars, it was used as a military port.

Figure 22.10 City plan, Ostia

368 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

During the second and first centuries BC, Ostia expanded beyond the walls of the original

colony. To feed the large population of Rome, imported food supplies were crucial. Ostia’s

harbor became a key port of entry for grain, notably from Sicily (late Republic) and Egypt (dur-

ing the Empire); the grain was stored in large warehouses (horrea) in both Ostia and Rome. As a

measure of the town’s growth, new walls were built ca. 80 BC, enclosing an area of 64ha. The old

castrum became the forum of the enlarged town, at the crossing of the two principal roads, the

cardo (north–south) and the decumanus (east–west).

The commercial importance of Ostia continued to grow, thanks especially to the intervention

of the emperors Claudius and Nero. In the early empire, the mouth of the Tiber proved too small

to accommodate the city’s maritime traffic. Moreover, the river and the port kept filling with silt.

As a result, an artificial harbor was built 3km north of the Tiber mouth, begun during the reign

of Claudius ca. AD 42 and finished under Nero. It measured ca. 1,000m across and had a light-

house, but was not adequately protected from winds. A canal linked the port to the Tiber; mod-

ern Rome’s airport, Fiumicino, built on the site of the ancient harbor, took its name from this

ancient canal. Under Trajan, ca. AD 112, a hexagonal harbor was added next to Claudius’s port.

An urban center developed by these harbors. Eventually, in the late empire, the settlement, now

walled, was granted status as a town separate from Ostia, with the name of Portus. But through

the second century, the harbor area remained under the control of Ostia, fueling Ostia’s growing

prosperity and expanding population: 50,000–60,000, according to one estimate (Meiggs 1973),

but only 22,000, according to another (Storey 1997).

Commercial buildings

Ostia has yielded much evidence for commercial complexes, warehouses, and shops. The Por-

tico of the Corporations (Piazzale delle Corporazioni), located behind the small theater, exempli-

fies the Ostian business center. The portico as well as the theater originated in the Augustan age,

but were remodeled in the late second or early third century AD. The business complex consisted

of a rectangular area, ca. 125m × 80m, framed by a double colonnaded portico; in the center lay

a garden with a small temple dedicated perhaps to Mercury. Behind the portico, sixty-one small

rooms served as branch offices for businesses dealing with shipping in the Mediterranean. Many

offices advertised their specialty in the mosaic pavement in front of their door. The image of

an elephant with the legend Stat(io) Sabratensium, for example, signaled traders from Sabratha in

Tripolitania (modern Libya) who dealt in ivory, and who may even have arranged the transport

of African elephants for the Colosseum. Like the variety of religious cults attested in Ostia, this

business portico speaks eloquently for the cosmopolitan character of the city.

Ostian warehouses include the Horrea Epagathiana et Epaphroditiana, built by two freed-

men, Epagathus and Epaphroditus, during the reign of Antoninus Pius (138–161). Brick was the

construction material. Indeed, at Ostia, instead of stone facing on a cement core (as at Pompeii),

regular courses of bricks were preferred. The exterior of the warehouse contained shops open to

the street. Over 800 shops (tabernae) are known from Ostia. They normally consist of a single tall,

deep, barrel-vaulted room, often equipped with a loft for storage or sleeping. A small window

over the door would provide lighting when the front door panels were closed.

A grand entry lined with brick columns and pediment marked the passage from the street to

the interior court of the warehouse. A double gate with iron bolts provided security. The inner

court was paved with mosaics and surrounded by arched porticoes. The building had sixteen

rooms on the ground floor. Stairs with separate entrances led to the upper stories, to offices and

possibly apartments for the owners.

POMPEII AND OSTIA 369

Some warehouses contained traces of the products traded. In one example north-east of the

forum, 100 dolia (huge pottery vats) were discovered sunk in the ground – a capacity of more than

84,000 liters of oil or wine.

Residential buildings: insulae

The term insula (pl. insulae), literally “island,” denoted a city block and also a multi-storied apart-

ment building, an essential component of urban housing during the Roman Empire. With popu-

lation increasing, urban residents often resorted to such housing. In Rome itself, some 90 percent

of the population lived in them. But ancient apartment buildings have survived poorly from the

capital; at Ostia preservation is much better.

The widespread construction of concrete insulae is partly attributable to the Great Fire in

Rome in AD 64, during the reign of Nero. Building materials for ordinary dwellings had been

wood and mud brick – cheap, but also highly combustible. After the fire, rebuilding was regu-

lated. Flame-resistant materials predominated; the use of wood diminished. Street widths were

specified. Building height was restricted to four or five stories maximum, ca. 24m under Nero,

20m under Trajan. Apartment buildings sprang up, structures that satisfied the new building

codes. As in many cities, however, we can imagine that regulations were not always followed,

that architectural quality and maintenance could be poor, and that side streets were dark, noisy,

and filthy.

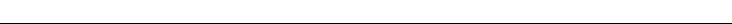

In appearance insulae resembled warehouses (Figure 22.11). They were large with sturdy walls

of concrete with brick facing, the brick normally exposed, not plastered over. The exterior might

Figure 22.11 Apartment house (reconstruction), Ostia

370 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

well include shops. Multiple entrances gave access into the building and to individual apartments

– a help if fires needed combating. Central courts, if present, provided air and light, supplement-

ing windows on the exterior.

The typical apartment was relatively spacious. A wide corridor hall with small rooms off it

dominated the plan. At either end lay the larger reception and dining rooms. Mosaics in geo-

metric patterns often covered floors; in poorer dwellings, patterns in the brick flooring sufficed.

Walls were painted simply. Utility rooms might include a kitchen, but no chimney. Toilets were

a luxury; normally one used common toilets on the ground floor. Other facilities available on the

ground floor might be running water and, in the court, an oven for baking. Easier access to these

features may explain why apartments on the lowest floors were the costliest, the most desirable.

A good example of an Ostian insula is the House of Diana of ca. AD 130–140, named after an

object found there, a terracotta relief plaque showing the goddess Diana.

In the late empire, from the third century AD, as Ostia’s population declined, luxurious free-

standing houses of the sort seen at Pompeii made a comeback. Despite the general commercial

decline, evidently Ostia had value as a place of retreat for wealthy Romans. The House of Amor

and Psyche of the fourth century AD exemplifies this trend. In contrast with Pompeiian houses,

the luxury of this house is displayed not in wall paintings, but in the decoration of polychrome

marble on the floor and the walls – a characteristic of the centuries to come in grand public build-

ings and churches as well as in the houses of the well-to-do.

CHAPTER 23

Rome from Nero to Hadrian

Imperial patronage and architectural

revolution

Rome, the capital city, continued as the nucleus of the empire until well into the fourth century

AD. We have traced the development of Rome from its origins through the reign of Augustus,

noting the many changes in its appearance brought about by the absorption of Etruscan and

Greek artistic and architectural forms, and by the changing requirements of civic life. This chap-

ter and Chapter 25 will follow the city through the imperial centuries.

Emperors of the first to early third centuries AD:

Julio-Claudians (AD 14–69)

Tiberius ruled 14–37

Gaius (Caligula) 37–41

Claudius 41–54

Nero 54–68

Three short reigns in 68–69

Galba, Otho, and Vitellius

Flavians (69–96)

Vespasian 69–79

Titus 79–81

Domitian 81–96

High Empire (96–193)

Nerva 96–98

Trajan 98–117

Hadrian 117–138

Antoninus Pius 138–161

Marcus Aurelius 161–180

Commodus 180–192

Pertinax 192–193

Severans (193–235)

Septimius Severus 193–211

Caracalla 211–217

Elagabalus 218–222

Severus Alexander 222–235