Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

372 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION: THE EMPIRE

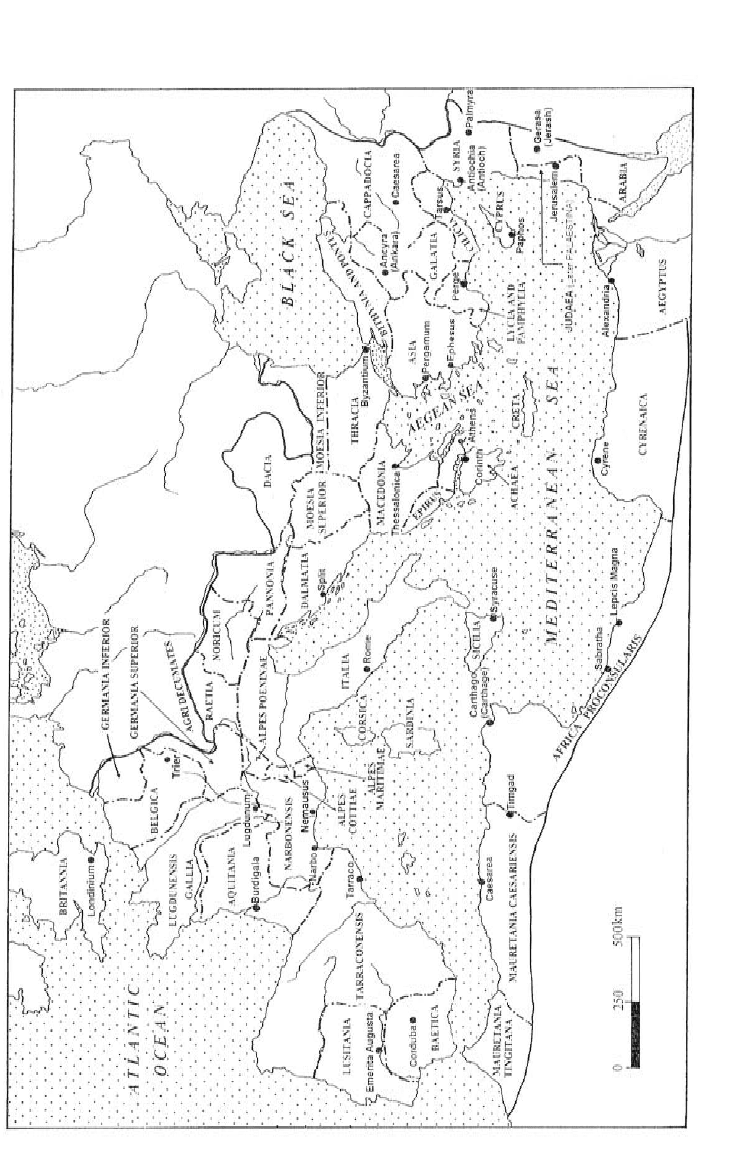

The two centuries following the death of Augustus marked the great period of prosperity and

power for the Roman Empire (Figure 23.1). The enormous territory, consolidated by Augustus

with the takeover of Egypt (30 BC) and the final conquest of Spain and Europe west of the

Rhine and south of the Danube, further enlarged with the conquests of Britain (AD 43) and

Dacia (roughly modern Romania) (AD 101–106), was held successfully against both external and

internal challenges. During this era of the Pax Romana (Roman Peace), agriculture, industry, and

trade thrived, bringing a stable and prosperous life to a large number of ethnically, religiously,

and linguistically diverse peoples.

This diverse population contained important social differences, with citizens, free non-citi-

zens, and slaves as distinct groups. Citizenship, although restricted at first, was eventually granted

to all free people in the third century. Slaves, always numerous, provided cheap labor. Despite

the social boundaries, throughout the first and second centuries it was possible to change sta-

tus, for a slave to become free, for a free non-citizen to become a citizen. In the later empire,

even among the citizenry socio-economic class distinctions would become more rigid, impeding

social mobility.

An important agent for stability, for peace and prosperity throughout the huge empire was the

army. Well organized and trained, the army consisted at first of citizens performing their civic

duty, later of professional soldiers. During the first two centuries AD, the army was primarily

stationed not in the heart of the empire, but along the 10,000km frontier. Never numerous, with

a maximum of 400,000 men, the army could maintain the frontier as long as attacks from outside

were not simultaneous; troops redeployed as needed to a zone of crisis. Only one neighboring

power could match Roman strength: the Parthians, ruling in Persia and Mesopotamia from 210

BC to AD 225. In later centuries, attacks would come simultaneously at different points along the

frontier, thus straining the Roman defenses.

The army helped spread Roman institutions to the provinces. As we have seen, the army

camp, or castrum, often developed into a town, with merchants and other providers of services

to the camp settling close by. Farmers worked to supply the army and the towns as well as their

own needs. In addition, new towns (coloniae) were created for retired army veterans, with the

principles of camp layout – two principal streets, the cardo and the decumanus, crossing at right

angles, with a forum at the crossing – followed in planning the settlement. The essential shrines

and institutions of the Roman state occupied places of honor, even if the local government

controlled its immediate affairs: the temple to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva; a shrine to the cult

of the defied emperor; the forum and its civic buildings. Other factors sustaining Roman social

and economic cohesion included the legal system developed in the Republic; a stable monetary

system, with coinage in gold, silver, and bronze, including small denominations for ordinary

transactions; and the well-maintained network of communications. Shared by countryside and

city alike, by the distant provinces and Italy, by Latin speakers and others, these features were

recognized by all as signs of membership in this far-flung community, the Roman Empire.

ROME: THE IMPERIAL CAPITAL

The major difference from Republican Rome is the rule and patronage of emperors. Augustus,

the first emperor, or princeps as he styled himself, appreciated that his rule marked a transition

from the Republic to something new. To ensure stability, he stressed continuity with what had

Figure 23.1 The Roman Empire during the reign of Hadrian: the provinces, with selected provincial capitals and other major cities

374 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

come before. His avoidance of personal ostentation, for example, counted as one way he paid

homage to ancient Republican ideals. His successors gradually abandoned Augustus’s low pro-

file, adopting instead the opulent trappings of kingship popular in the Hellenistic world. This

changing concept of kingship was mirrored in the appearance of Rome, in the grandiose palaces,

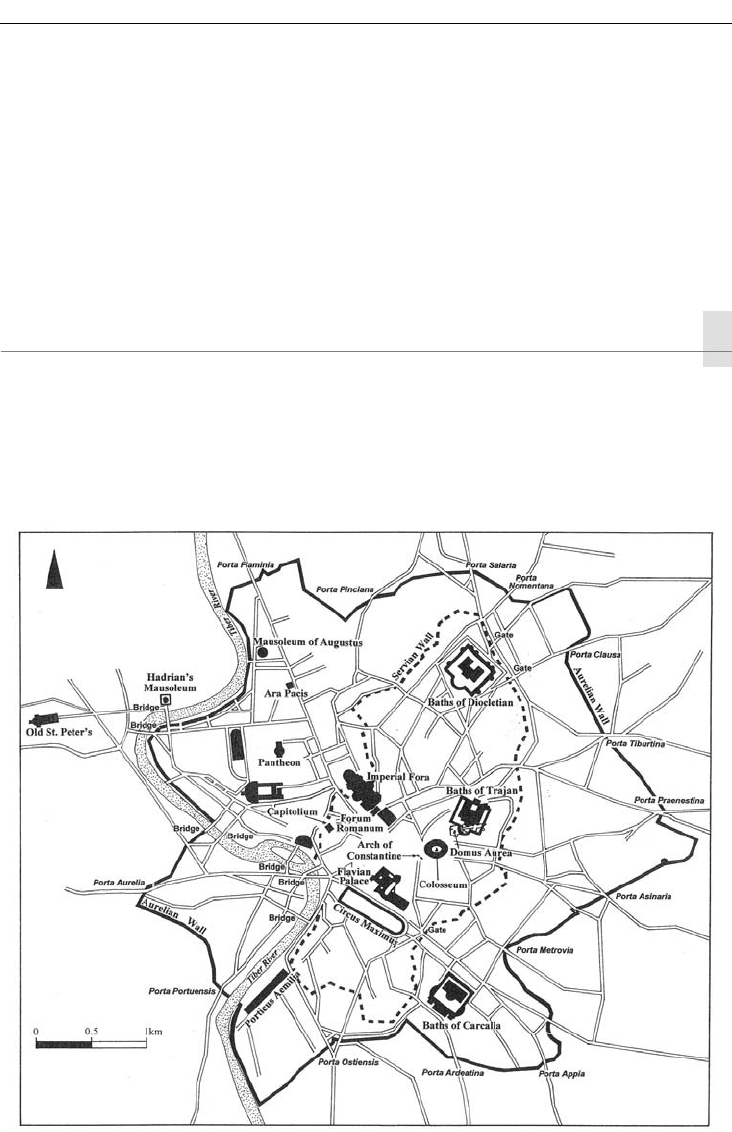

temples, commemorative monuments, and civic buildings commissioned by the emperors (Fig-

ure 23.2). Embedded in this architecture is a revolution in forms, made possible by the use of

concrete, a breaking away from the traditional post-and-lintel system enshrined in the conserva-

tism of Greek architecture. The essentials took place within a short time, from the reigns of Nero

to Hadrian. The effects would continue to resound ever after in European and Mediterranean

architecture.

PALACES

The population of Rome swelled to over one half million, possibly up to a million by the first

century AD, huge for an ancient city, but befitting the capital of such an enormous state. Most

people lived in squalor, in ramshackle multi-story apartment buildings along narrow streets unlit

at night. Disaster was endemic, with collapsing buildings and fires, the most famous of which

was that of 64 during the reign of Nero. The wealthy, served and protected by retainers, were

Figure 23.2 City plan, Rome, imperial period

ROME FROM NERO TO HADRIAN 375

spared such hardships and could enjoy the stimulations of this great city. Their luxurious dwell-

ings have largely disappeared, but we can imagine their houses as grand versions of those exam-

ined at Pompeii. In contrast, the residences of the emperors have survived to a certain extent.

Three palaces give a perspective on the royal expectations in the post-Augustan centuries: the

Domus Aurea (Golden House) of Nero; the Flavian Palace on the Palatine Hill; and Hadrian’s

Villa at Tivoli, outside Rome. All were far more sumptuous than Augustus’s house. In addition,

all three display architectural innovations that distinguished this period.

The Domus Aurea

Nero became emperor in 54 at the age of 17, and soon gained a reputation for capriciousness and

cruelty. He was also given to grandeur, best expressed in his ambitious projects for a new palace.

Unsatisfied with Tiberius’s Domus Tiberiana on the Palatine Hill, he began a new residence,

the Domus Transitoria, which extended from the Palatine across low ground to the Esquiline

Hill to the north. This palace was destroyed in the great fire of 64, which started in the Circus

Maximus and spread northward with devastating results. Burned completely was half the center

of the city: three of the city’s fourteen administrative regions, with an additional seven regions

damaged. Nero quickly set out to build a replacement, with the help of Severus, an architect, and

Celer, an engineer. Thanks to annexation of additional land, the new palace, known as the Domus

Aurea, the Golden House, occupied an even larger tract of land in the heart of the city than did

its predecessor, ca. 50ha. A combination of parks, lakes, and buildings, the Domus Aurea was

a country villa placed in a downtown urban setting. In its large entrance court stood a colossal

bronze statue of Nero by the sculptor Zenodorus. According to the late first century writer Sue-

tonius, the statue measured 120 Roman feet (= 35.48m) in height.

An artificial lake was created in the low lying land beyond (the site of the later Colosseum).

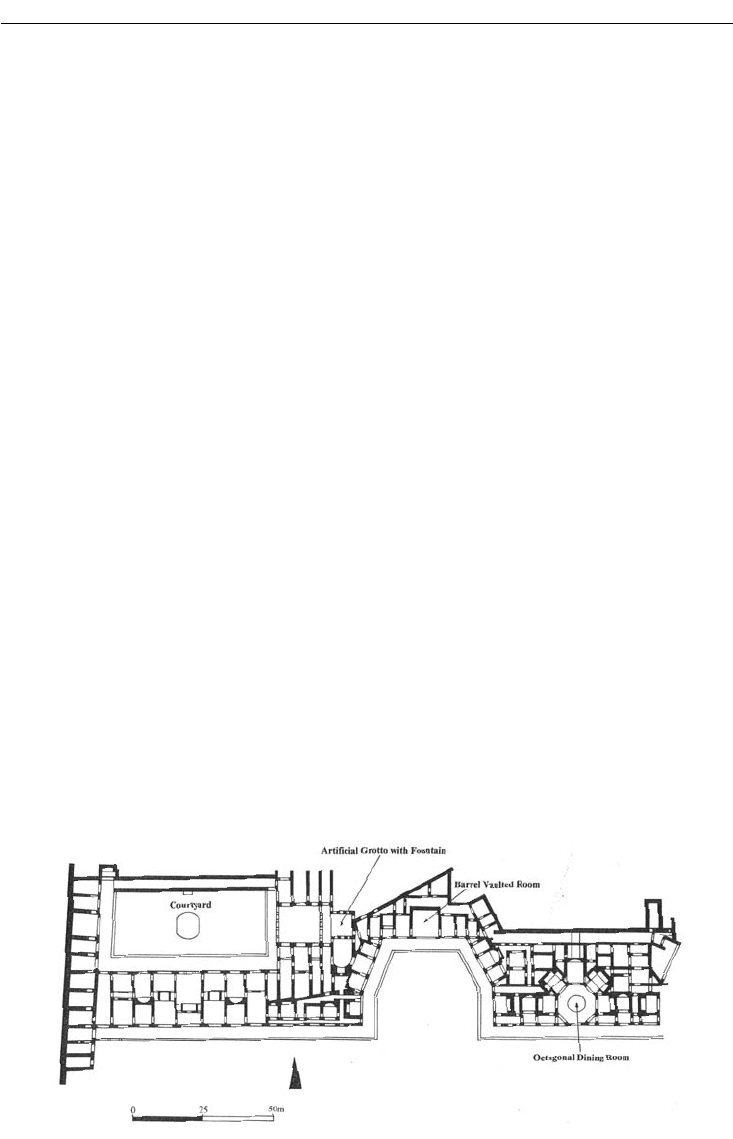

The palace proper, the residential wing, stood on the south slope of the Esquiline hill (Figure

23.3). The whole complex – lake, gardens, and residence – was built over after Nero’s death,

probably as a way of reviling his memory (damnatio memoriae). The descriptions of Suetonius and

Pliny, however, together with the remains of architecture and wall paintings discovered in mod-

ern times make clear the lavishness of the building. Of prime importance was the central dining

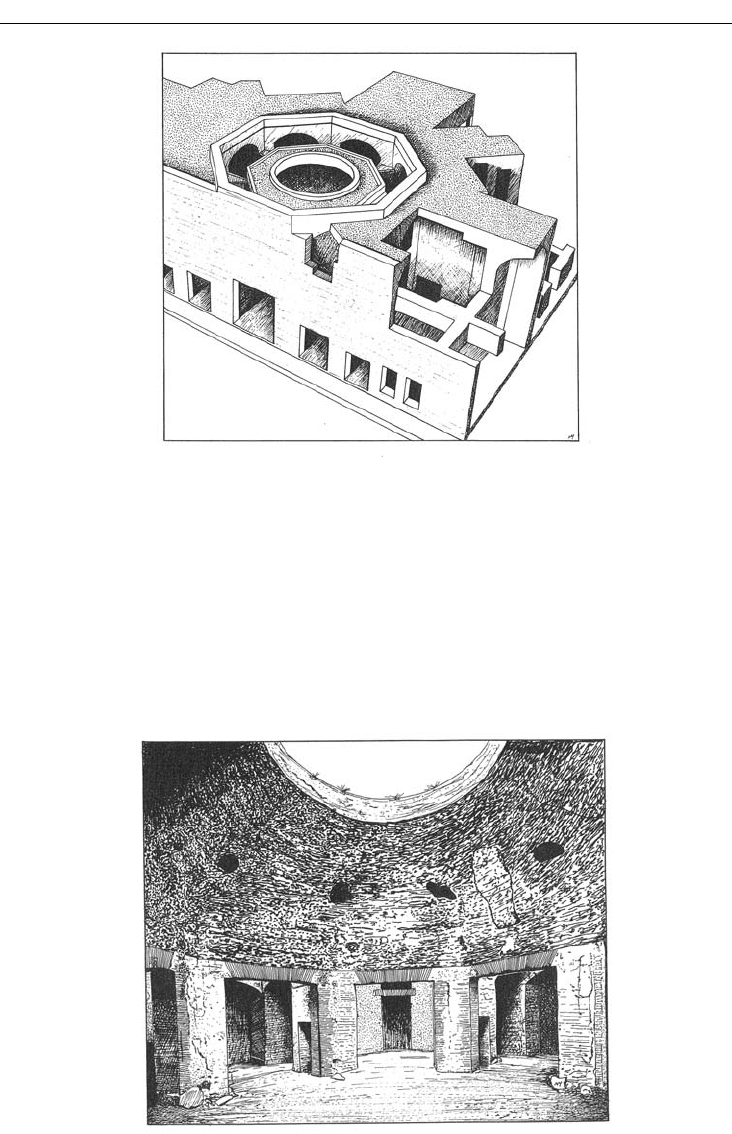

room, an original and influential piece of architectural design (Figures 23.4 and 23.5). Octagonal

Figure 23.3 Plan, Domus Aurea, Rome

376 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

in plan, the room had a complicated but regular arrangement of recessed niches alternating with

the straight walls. Most unusually, a revolving ceiling (perhaps some sort of canopy?) represent-

ing the heavens covered the room; above it was a dome. The ceiling is long gone, but the dome

survives: a segmented dome, that is, not a continuous half sphere, but a series of eight curving

panels, made of concrete. Round or octagonal spaces had heretofore been roofed with straight-

sided conical roofs, like the traditional Chinese laborer’s hat. The dome, which curves out as it

descends, represents a new concept of roofing. The spherical dome, which we shall see shortly

in the Pantheon, is simply the arch form turned in a full circle. Since the Romans had already

Figure 23.4 Octagonal Dining Room from the outside (reconstruction), Domus Aurea, Rome

Figure 23.5 Octagonal Dining Room, Domus Aurea, Rome

ROME FROM NERO TO HADRIAN 377

made the arch a preeminent feature of their architecture, their developing of the dome should

not surprise us. The Domus Aurea illustrates as well the Roman interest in curvilinear forms and

interior space, both antithetical to Greek architectural design, in which the rectilinear post-and-

lintel structure and the exterior view dominated.

The Flavian Palace (Domus Augustiana)

The Palatine Hill, the site of Augustus’s home, the House of Livia, and the wattle-and-daub hut

attributed to Romulus, continued through the imperial centuries as the location of the royal

residence. Indeed, the name of the hill often denoted the residence: the Palatium, or, in English,

the palace.

Tiberius, Augustus’s successor, replaced the modest House of Livia with a grander residence

on the north side of the hill overlooking the Forum Romanum. This, the Domus Tiberiana, was

refurbished in the late first century by the Flavian emperor Domitian, and supplemented by a

much larger palace on the south half of the hill, the Domus Augustiana (or Augustana), multi-

storied, full of dramatic views and architectural surprises, the design of the architect Rabirius.

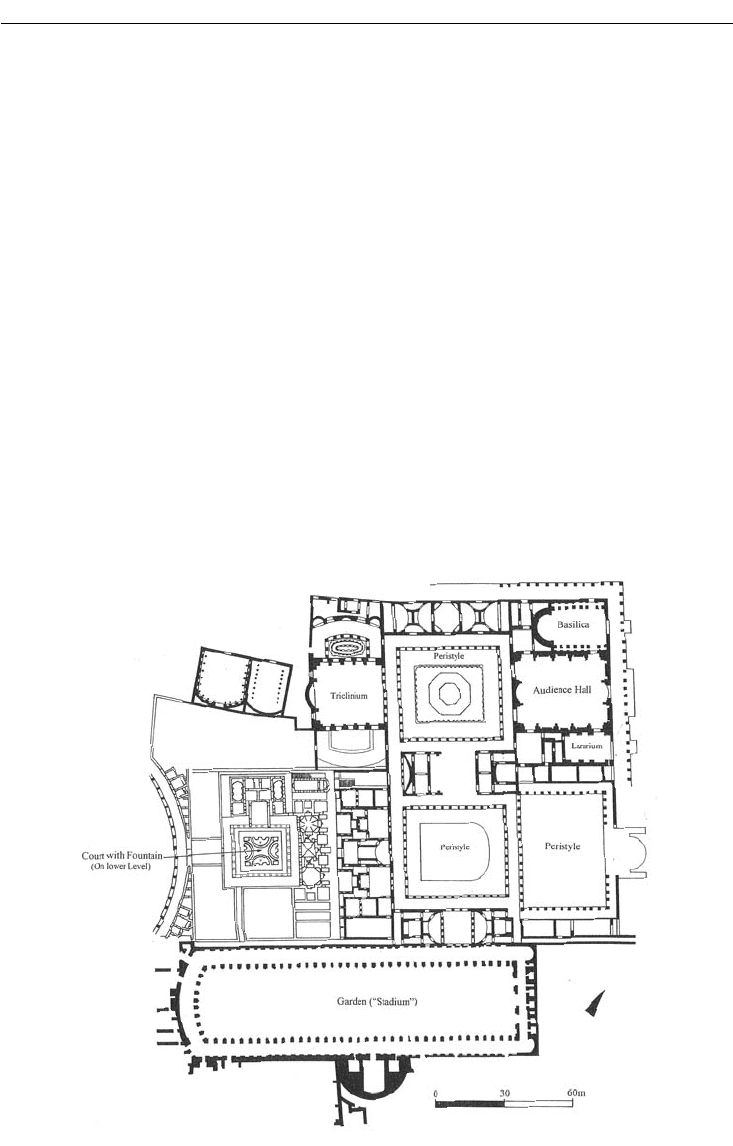

The Flavian Palace, as we might call the new building, consisted of two sections, one public or

official, the other private (Figure 23.6). Entry into the official part came from the north, through a

modest off-center doorway into a plain but large vaulted room. From there one entered the north

side, with three state rooms. The basilica, a rectangular hall with an apse at the south end, was roofed

with a barrel vault, unusual for the period. The center room served as the royal audience hall, with

Figure 23.6 Plan, Flavian Palace (Domus Augustiana), Rome

378 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

the imperial throne placed in the apse at the south. The smallest of the three rooms was the lararium,

the shrine for the household gods. To the south of this block lay a peristyle court, flanked by small

rooms with curvilinear plans; beyond the court one reached the triclinium, the large formal banquet

hall. Doors opened from the long sides of this room onto gardens with oval fountains.

By passing from the peristyle court into an adjacent peristyle garden, one entered the private

sector of the palace. From this point the hill sloped down toward the Circus; in compensation,

the palace became multi-storied. In fact, a formal entrance existed on the lowest level, through

a curving portico on the south; one then proceeded into a court with a fountain. North of the

court lay octagonal rooms with domed roofs, successors of the octagonal dining room of the

Domus Aurea. The influence of the Domus Aurea is seen as well in the frequent use of curvilin-

ear spaces, made possible by the use of concrete.

To the east of this private block was a large garden in the shape of a stadium, 160m × 50m,

lined on three sides by a two-storied portico. From its south end the imperial box overlooked

the Circus Maximus. Direct access from palace to viewing stand is a design feature that will be

repeated in the fourth century capital, Constantinople.

Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli

One emperor who chose not to live in the center of Rome on the Palatine Hill was Hadrian.

Hadrian stood out in other ways, too. He traveled relentlessly throughout the empire, for peace-

ful as well as military purposes. The most ardent

champion of Greek culture since Augustus and

Nero, he renewed official interest in Greek art

and architecture in the capital city.

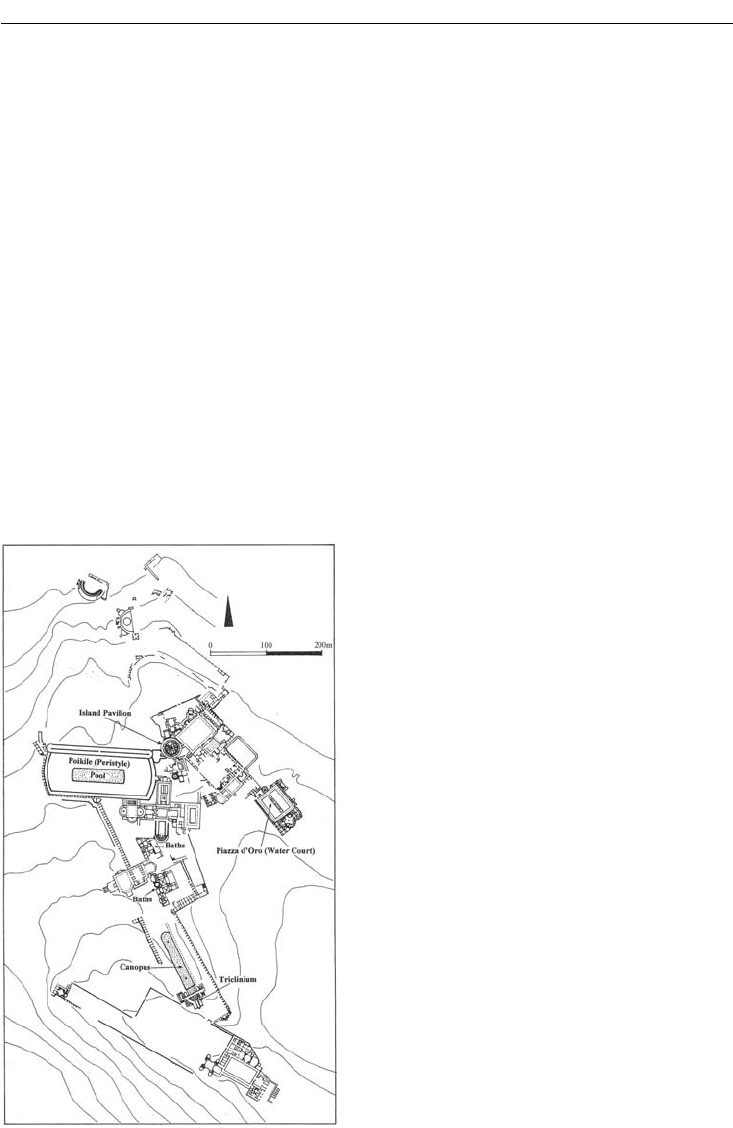

The residence he built 25km east of Rome at

Tivoli is known as Hadrian’s Villa (Figure 23.7).

This sprawling (ca. 120ha), eclectic collection

of pavilions and courts, water features and gar-

dens, and substantial buildings has survived well,

thanks to its suburban location. The architec-

ture ranges from the standard to the surprising.

Examples of the latter include reminiscences of

places Hadrian visited on his travels. The “Island

Pavilion” (traditionally but misleadingly called the

“Maritime Theater”), a building constructed on a

circular island, recalls Herod the Great’s Hero-

dium palace (23–15 BC), 12km south of Jerusa-

lem. Egypt is represented throughout the villa by

sculpture in pharaonic styles. A traditional iden-

tification of a grotto-like banquet hall at the end

of a long narrow pool as an Egyptianizing com-

plex designed to recall the Nile has recently been

dismissed, however; MacDonald and Pinto have

newly labeled these two features, long known as

the “Canopus” after the Egyptian town famous

for its Temple to Serapis, as the “Scenic Triclin-

ium” and the “Scenic Canal” (Figure 23.8).

Figure 23.7 Plan, Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli

ROME FROM NERO TO HADRIAN 379

Like the Domus Aurea, Hadrian’s Villa includes innovative architectural design; Hadrian

took an active interest in architecture, and may have designed certain features himself. The

half dome of the Canopus/Scenic Triclinium is a segmented dome, but with segments that

curved horizontally as well as vertically – possibly the “pumpkin” dome scorned by the promi-

nent architect Apollodorus of Damascus. Atop the colonnade re-erected at the north end of

the Canopus/Scenic Canal, one sees a Roman variant on the standard Greek entablature.

Horizontal members alternate with arches, the arches thereby breaking the traditional hori-

zontal trabeation of Greek architecture. This alternation became standard in later imperial

architecture.

Another striking complex is the Piazza d’Oro (renamed by MacDonald and Pinto as the

“Water Court”), a large building (ca. 59m × 88m) consisting of an octagonal vestibule, a large

porticoed court with a water canal in the center, and, opposite the entry, a nymphaeum (fountain)

chamber. This room must have been astonishing, with a fountain in the center, a fountain in each

of the four corners, and a sixth broad curving fountain at the rear, opposite the courtyard. Also

astonishing is its curvilinear ground plan, reproduced at the level of architrave, held up by slender

columns. What sort of roof this chamber had, if any, is unknown. Although pointing to trends

in later Roman architecture, the oval and curvilinear forms recall Baroque design in Rome 1,500

years later, especially the architecture of Borromini.

TEMPLES

Religious architecture, ever conservative, still relied heavily on the Greek and Tuscan traditions,

although the spirit of innovation burst forth even here. Striking use of the traditional and the

new can be seen in the two major temples built under Hadrian, the Pantheon and the Temple of

Venus and Roma.

Figure 23.8 Canopus (Scenic Canal), Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli

380 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

The Pantheon

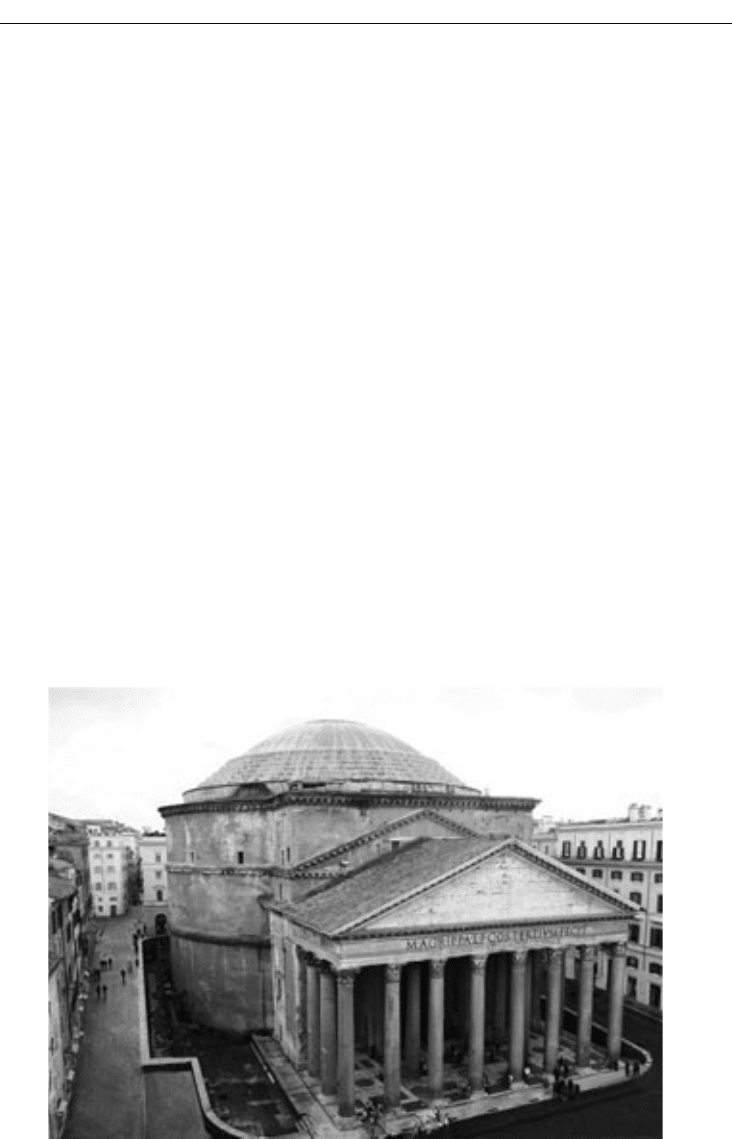

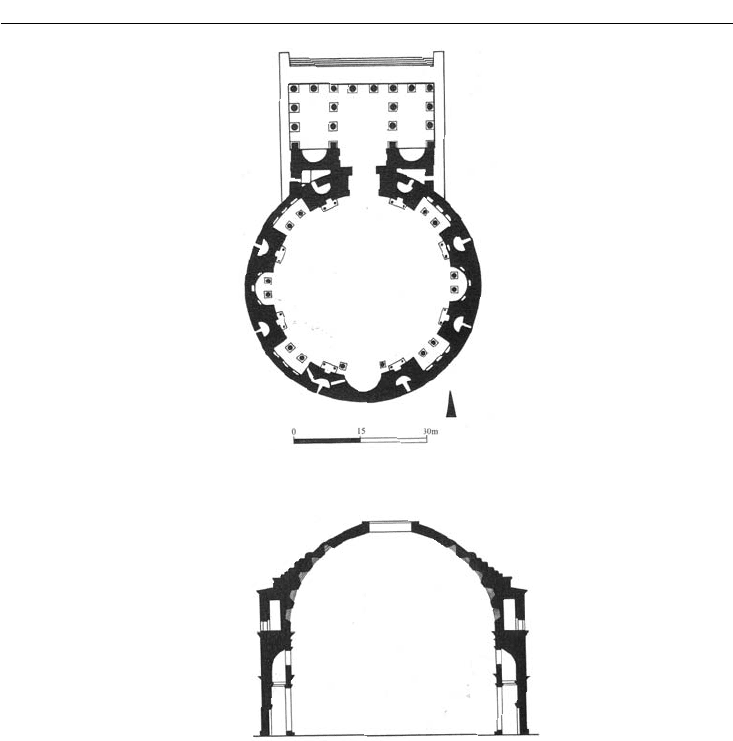

Hadrian was responsible for rebuilding the Pantheon, a temple dedicated to all gods (Figures

23.9, 23.10, and 23.11). The Pantheon was originally built in 27 BC by Marcus Agrippa, a confi-

dant of Augustus. Damaged in a fire of AD 80, the temple was restored by Domitian. Hadrian’s

version was a complete rebuilding; the architect of this unique design is unknown, but Hadrian

himself surely took a great interest in it. All traces of the earlier plan were obliterated, although

Agrippa’s dedicatory inscription was kept, curiously enough. Turned into a Christian church

with few modifications of the Hadrianic structure, the building has been extremely well pre-

served. Today, however, the setting differs: the surrounding ground level is much higher than in

antiquity, and the rectangular court lined with porticoes that originally lay in front of the temple,

focusing attention on the temple’s entrance, is now replaced by a square with streets heading off

in all directions.

The construction of Hadrian’s Pantheon began in ca. 117 and was finished by 126–128,

according to its brick-stamps. Brick-stamps represent a distinctive component of the archaeo-

logical record of imperial Rome. Baked bricks were used as building materials from the time of

Augustus, with great popularity from Nero to Hadrian. The bricks made in and around Rome

were stamped with different types of information from the reign of Augustus through Caracalla,

then again from the reign of Diocletian (284–306). This information could include: the type

of product; the source of the clay or the name of the brickyard; the owner of the clay source;

the brick maker; or the consuls in office when the brick was made. This last is especially useful

for dating purposes from AD 110 to 164, the period when consuls might be named in stamps,

because consuls, well known from literary sources, served for one-year terms.

The unusual design of the Pantheon combined traditional Etruscan (Tuscan) and Greek archi-

tectural features with innovations. The temple consists of two parts: a Tuscan-Greek porch

Figure 23.9 Pantheon, Rome

ROME FROM NERO TO HADRIAN 381

approached from a large colonnaded court, and, behind, a circular cella covered by a hemispheri-

cal dome. The two join awkwardly by means of an intermediate zone with niches. The porch,

deep with a broad flight of steps on the front only and raised on a podium, all in the Tuscan

manner, is covered with a pediment and gabled roof held up by monolithic columns of Egyptian

granite with Corinthian capitals. Marble, widely used, gives an elegant effect. The cella, in con-

trast, is made largely of concrete, with brick and stone elements. Here the builders developed

innovative construction techniques, although much is hidden from the visitor’s eye. The walls

are not solid, but are composed of vaulted spaces, one on top of the other. The vaults of bricks

redirect the downward pressure toward the eight massive piers in the circle and give variety and

resilience to the structure. The dome itself is made of concrete that was poured over a huge

wooden frame, the weight of the concrete lightened with inclusions of pumice instead of the

heavier aggregate used in the lower walls.

Although the hemispherical dome springs from the internal wall at a height equal to the radius

of the dome, the exterior wall rises well above this starting point, permitting the extra support of

buttressing against the lower part of the dome. Because of this compensation, from the outside

Figure 23.11 Cross-section, Cella, Pantheon

Figure 23.10 Plan, Pantheon