Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

392 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

and the end of this book, but continue on through the Middle Ages and the modern era. They

were variously ruined quickly or slowly; built over or left exposed; pillaged for building materials;

reconverted and reused; or surviving virtually intact – then slowly brought back to the conscious-

ness of the public from the Renaissance on, through the interests and efforts of artists, architects,

historians, and archaeologists (amateur and professional), popes and politicians, and indeed the

public at large.

CHAPTER 24

Roman provincial cities

“Hunting, bathing, having fun, laughing – That is living!” (Finley 1977: 73). This phrase (in Latin)

was discovered scratched onto the paving of the forum of Thamugadi, a Roman city in Algeria,

and for many Romans of the prosperous and peaceful fi rst through early third centuries it must

indeed have expressed their view of the ideal life. We have already examined Roman cities in the

Italian peninsula, the heartland of the Roman Empire: Cosa, Ostia, Pompeii, and Rome itself.

Let us now travel outside Italy to see how provincial cities resemble or differ from those in the

heartland. The candidates for a visit are many. How to choose? Since we have been tracking the

development of urbanism in the eastern Mediterranean and Near East, we shall concentrate on

these regions, exploring to what degree Roman cities continued earlier traditions. Moreover,

the evidence from the eastern half of the empire is particularly rich. Shifts in habitation in this

region led to the abandonment of many major Roman cities – and hence to their preservation.

The western empire deserves our attention, too. For the most part, the pre-Roman past of this

region has lain outside the scope of this book. Apart from Phoenician and Greek settlements in

coastal Spain and Mediterranean France, an urban tradition did not develop there until brought

by the Romans. The local contexts are thus quite different from those in the eastern empire. As

a result, the study of western Roman cities strikes a different tone.

We shall examine ten cities: seven examples from the eastern Mediterranean, and three from

western Europe. Our exploration will begin with Athens, and then move in a clockwise direction

to Ephesus and Pergamon, Perge, Palmyra, Jerash, and Lepcis Magna. We shall then cross the

Mediterranean to France, England, and Germany, to finish with a look at Nîmes, London, and

Trier (see the map, Figure 23.1). These cities raise questions about Roman cities that we should

keep in mind as we explore our examples. Seven themes seem of particular interest. First, the

blend of Roman culture with pre-existing cultures, and how this mix was expressed in the urban

landscape will be key in the eastern region with its several thousand years of urban experience.

Athens was a cultural heirloom for the Romans, a seat of revered Greek culture, but nonetheless

the Romans introduced their favorite building types. Second, religious syncretisms, or the mul-

tiplicity of cults, result in variations of temple and tomb structures. In Ephesus and Pergamon,

Egyptian cults mingled with Greek and Roman religions, whereas in Syrian Palmyra, the Classical

mixes with the native Near Eastern. Third, the varying economic bases of towns, dependent on

the geographic location of cities, may affect the appearance of cities, and the experiences of their

inhabitants. Fourth, city layouts may vary, with newly founded cities having different types of

plans from older, established cities. In addition, local topographies can affect city plans. Fifth,

building types and plans, the elements of the physical world of the city: to what degree are they

uniform throughout this region, to what degree do they differ? Sixth, the traditions of construc-

tion: to what degree were these techniques local, to what degree brought from Italy? Seventh and

last, we are also interested in benefactors, imperial and local: who were they, and what did they

394 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

hope to gain from their gifts to their city? In sum, what constitutes a Roman city? Can we indeed

recognize a Roman city, no matter where we might be in the Empire?

ATHENS

“Greece, the captive, took her savage victor captive, and brought the arts into rustic Latium”

(Alcock 1993: 1). So wrote Horace about the lasting power of Greek culture for the Romans

despite the latter’s military conquest of the Greek world. For the Romans, no city better symbol-

ized the achievements of Greek culture than Athens. Although not the major commercial and

administrative city of the Greek peninsula under Roman rule, now organized as the province of

Achaia – that was Corinth, destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC, then resettled as a colony in 44

BC – Athens retained its special aura. The city maintained its reputation as an intellectual center

for many centuries, even after the crippling attack in 267 of the Herulians, a Germanic tribe from

eastern Europe. The end of its long tradition finally came in 529, when the Byzantine emperor

Justinian closed its famous philosophical schools.

When a Roman emperor wished to emphasize his philhellenism, he would donate a magnificent

new monument to Athens, thereby paying homage to this city and to the intellectual and artistic

life that it had nurtured for centuries. The two emperors who drew most upon Greek models for

urban architecture were Augustus and Hadrian. Indeed, they both made gifts to Athens (see the

map of Athens, Figure 14.1). Augustan monuments include the Temple of Roma, a small circular

temple placed east of the Parthenon, its Ionic order copying that of the recently refurbished Erech-

theion; and the Roman Agora, a porticoed rectangular market square built to the east of the older,

established agora. The most important building of this period was the large Odeion of Agrippa, a

covered theater built in 15 BC in the older agora, a donation of Augustus’s son-in-law.

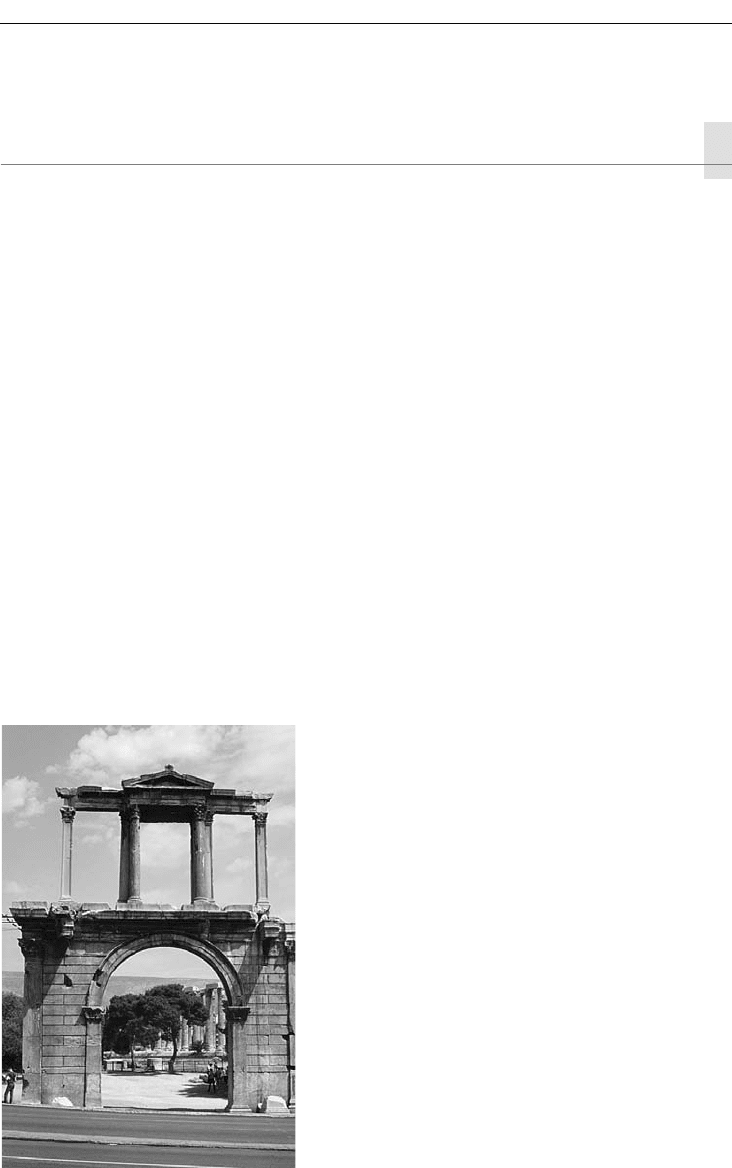

Hadrian visited Athens in 133; in honor of his trip, he built a monumental gate (Figure 24.1).

The gateway combines Roman and Greek forms: a Roman arch below, but Greek post-and-lintel

Figure 24.1 Hadrian’s Arch, Athens

ROMAN PROVINCIAL CITIES 395

forms in the upper tier. It marks the boundary between the established earlier Greek city and

the sector newly developed by the Romans, enclosed in an extension of the city wall. This func-

tion was noted by the inscriptions carved on its lower friezes: “This is Athens, the ancient city

of Theseus” (on the west) and “This is the city of Hadrian, not of Theseus” (on the east). Other

building projects of Hadrian included a library, built next to the earlier Roman Agora, and the

completion of the Olympieion, the huge temple to Zeus begun in the late sixth century BC and

much advanced, but not finished, in 175–164 BC. The Olympieion, at least, lies just to the east of

Hadrian’s arch, thus inside Hadrian’s city.

Imperial patrons were not alone in making gifts to the city. Local philanthropy existed, too.

Herodes Atticus, a wealthy Athenian of the mid-second century, donated the large odeion built

into the south-west slope of the Acropolis as a memorial to his wife, Regilla.

After the Herulian attack of 267, a new defensive wall was built, the “Valerian Wall.” The area

enclosed was much smaller than that of the Themistoklean Wall with its Hadrianic extension,

and shows clearly how dramatically the city had shrunk. However great its lingering prestige,

Athens had now become an economic backwater, a minor town important only for its region.

This situation continued through the Middle Ages and the Ottoman period. In 1834, the for-

tunes of the city once again changed sharply, with its selection as the capital of the recently

independent Kingdom of Greece.

EPHESUS AND PERGAMON

The vital centers of the Greek areas of the Roman Empire lay not on the Greek peninsula, but

further east: on the east Aegean coast in the province of Asia (Ephesus and Pergamon), in the

province of Syria (Antioch, today the Turkish city of Antakya), and Egypt (Alexandria) – all well-

established in the earlier Hellenistic period. Ancient remains of the last two cities are difficult

of access, being overlain by silting (Antioch) and later occupation (both). Ephesus, however,

and much of Pergamon have been the objects of rewarding archaeological excavations, thanks

to shifts in settlement location from ancient to medieval and modern times that have made the

ancient remains easier to reach.

Pergamon in Roman times we have already touched upon in Chapter 18. The Trajaneum, or

Temple of the Divine Trajan, of the early second century was the main building of this period

on the Acropolis. It set the orientation for the grid plan that determined orientations of new

construction even down on the plain below. We also noted the Asklepieion, the sanctuary just

out of the city, with its important construction of the second century.

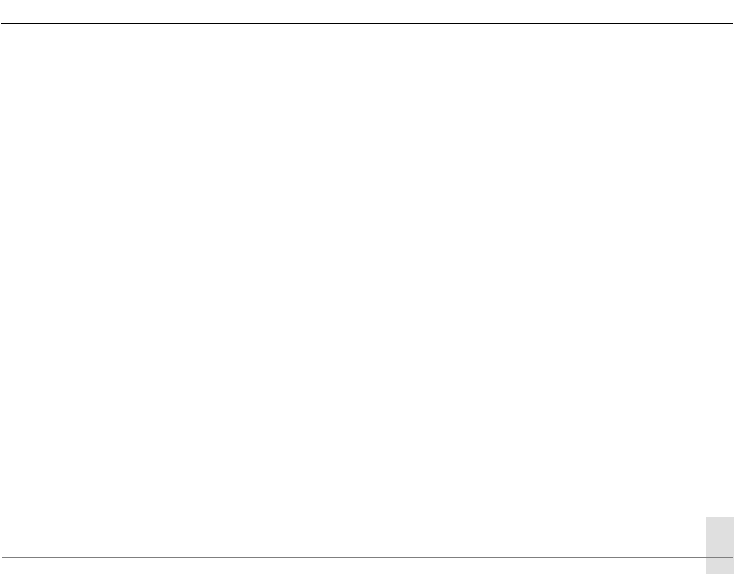

Ephesus was the capital of the Roman province of Asia, with a large population estimated

at 250,000. Occupied since the Bronze Age, it was an important Greek and then Roman city,

internationally famous for its Temple of Artemis and blessed with good harbor facilities. In

late Roman times, its commercial and political prominence came to an end, as silting from the

Cayster River filled the harbor. Today the Roman ruins lie several kilometers from the Aegean

coastline (Figure 24.2). By Justinian’s time (sixth century), the site of the Roman city was given

up in favor of a defensible inland location, around the tomb and basilica church of St. John, the

apostle and evangelist.

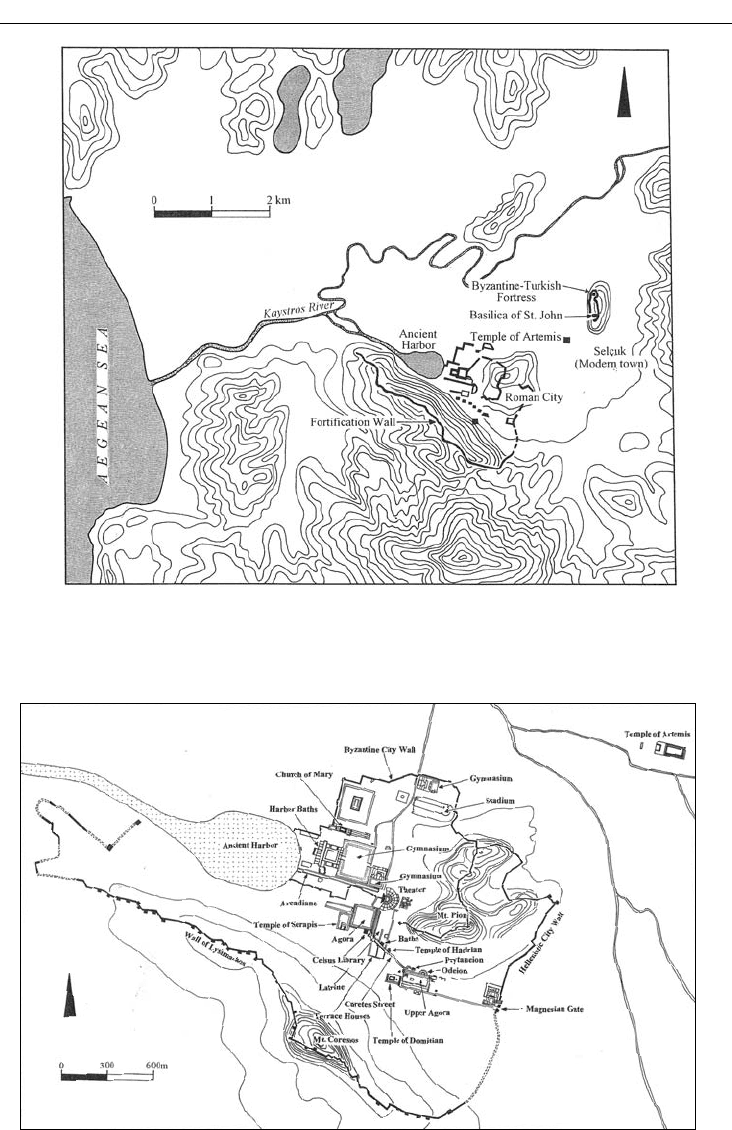

The Roman city has been brought to light by Austrian excavations conducted since 1897. A

walk through the extensive ruins gives a good impression of the grandeur of this major Roman

city (Figure 24.3). The topography has much affected the city’s layout, for the city lies between

two hills. A central street (Curetes Street), dominating the plan, runs downhill from the west

396 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Figure 24.2 Regional plan, Ephesus and environs

Figure 24.3 City plan, Ephesus

ROMAN PROVINCIAL CITIES 397

through the saddle between the two hills. On the south hillside, at least, excavations have revealed

well-preserved houses of the wealthy, arranged on terraces. The main street continues down to

the Library of Celsus, then turns north toward the Greco-Roman theater (where St. Paul was

denounced as a troublemaker to the assembled multitude by a maker of statues of Artemis),

then west again going straight to the harbor. This last leg is a fourth- or fifth-century reworking,

complete with the then still unusual addition of street lights.

Excavation projects at large Greco-Roman sites in Turkey have been encouraged by the gov-

ernment to restore selected buildings. The Austrian excavators at Ephesus are now focusing on

the hillside houses mentioned above. Earlier, they restored the façade of the Library of Celsus

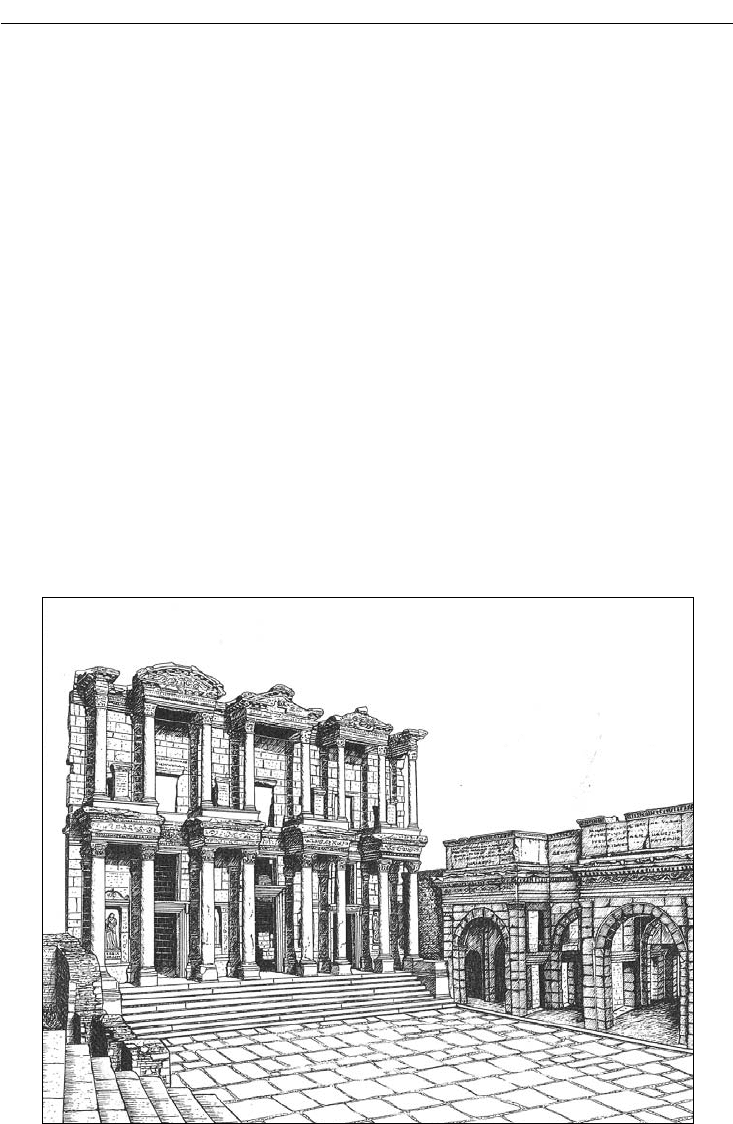

(Figure 24.4). This library was built in 110 by Gaulius Julius Aquila in honor of his father, Gaius

Julius Celsus Polemaenus, proconsul of Asia in 106–107. Its beautiful façade is decorated with

projections and niches that recall the stage buildings of Roman theaters. Statues personifying

qualities of Celsus, such as Wisdom and Virtue, fill the niches on either side of the central door-

way. Behind the façade, the building is simpler and smaller. A single interior room originally was

equipped with three stories of galleries for the storage of manuscripts. Celsus himself was buried

in a basement chamber, in a lead coffin placed inside a marble sarcophagus, found in situ but not

opened. It was rare for an individual to be buried inside the city limits, and is a mark of Celsus’s

distinction.

In the eastern Mediterranean, local building traditions were hardly changed by the arrival of

the Romans. Cut stone was still favored, whereas the concrete and brick constructions typical

in Italy and the central and western Mediterranean were unusual. A striking contrast of the two

Figure 24.4 Library of Celsus and South Gate of the Agora, Ephesus

398 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

types of construction can be seen in two temples traditionally (although not without controversy)

attributed to Serapis: one at Ephesus, the other at Pergamon. Serapis was the Ptolemaic hybrid of

the Egyptian Apis with the Greek Hades (Chapter 18); his cult remained popular both in Egypt

and in regions with commercial contacts with Egypt during the imperial centuries. At Ephesus,

the Temple of Serapis of the early second century looks like a standard Greco-Roman temple.

Its post-and-lintel structure comes from the Greek tradition, as does its decoration, Corinthian

columns on the porch, and carved architectural decorative motifs such as bead-and-reel and egg-

and-dart. Roman in concept is its imposing frontality, with steps leading up to the entry. Indeed

the front view is all there is, for the temple is nestled against the hillside, built on a terrace cut out

of the bedrock. One cannot walk around it. The cella is a single room, modest in size; cuttings

for water channels indicate the importance of water in the cult. To the Egyptian tradition belongs

the massive scale of the temple, especially its front porch. The columns are monoliths 14m–15m

high, and the door frame is constructed of colossal blocks. The wheels that held the ends of the

gigantic door flaps rolled along large arcs cut into the floor blocks.

The Temple of Serapis, or the Temple of the Egyptian Gods, at Pergamon is quite different.

Known today as the Red Hall (Kızıl Avlu, in Turkish), this building complex lies at the base of

the acropolis hill, on flat ground. The Red Hall is made of baked bricks and concrete, an unusual

choice in Roman Asia Minor. Massive, the building rose two stories high. Marble veneer would

have covered the walls, but that has been stripped away. A Christian church was later constructed

inside (also the fate of the Serapeion at Ephesus), thereby altering and even destroying some of

the pre-Christian architectural features.

The identification of the Red Hall as a temple for Egyptian gods is not certain. However,

several striking features make this likely. The complex is extremely large. The main building

measures 60m × 26m. It is flanked by round towers with a smaller court in front of each. In front

of this three-part structure lies a huge court (ca. 200m × 100m), today mostly covered by modern

buildings. Under this court the Selinus (mod. Bergama) River still flows; it has been proposed

that this river was symbolic of the Nile. In addition, caryatid columns used in the smaller courts

that flank the main building have been carved on two sides with men and women, both in realis-

tic Greco-Roman style, but some wearing Egyptian pharaonic headgear. The Red Hall contained

a colossal statue, perhaps of Serapis. This statue was hollow, and a priest could climb into it and

speak out, as if he were the god speaking. The hole in the statue base can still be seen.

A current project of the German Archaeological Institute in Istanbul to document and analyze

afresh this building may provide new answers about its identification and function. Whatever the

results, the Red Hall remains unique in Asia Minor, a monumental complex constructed in brick,

a construction technique brought from afar. Clearly the effect sought from its scale, layout, and

materials was very special indeed.

PERGE

Royal patronage has proved an important factor in the embellishment of towns, likewise the

interest of wealthy benefactors, such as Herodes Atticus. Almost always these patrons were men.

Unusual, then, is the city of Perge in Pamphylia, on the south coast of Asia Minor, where the

most famous benefactor was a woman, Plancia Magna. Of distinguished family, Plancia Magna

was nonetheless no mere appendage to male glory; inscriptions of dedications and commemora-

tions found in the Turkish excavations at Perge have revealed that in the early second century

she was the leading force of her family.

ROMAN PROVINCIAL CITIES 399

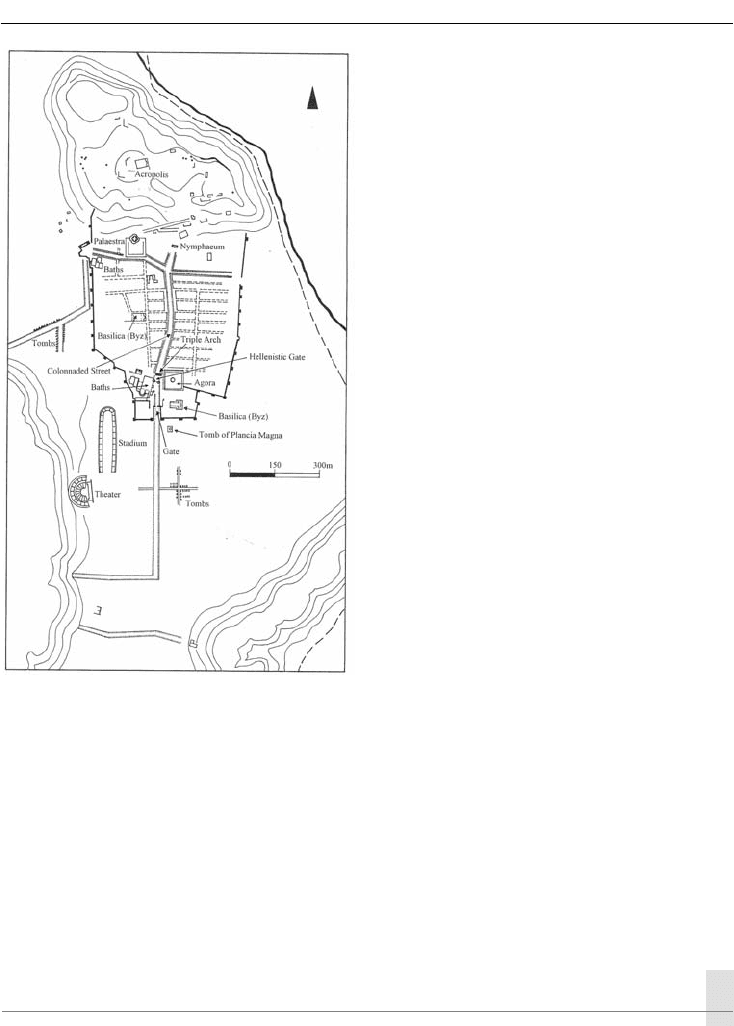

Perge lies a few kilometers inland from

the port town of Attaleia (today’s Antalya)

focusing on a low flat hill, the sort of forma-

tion much appreciated in this area. For much

of Perge’s history, the flat hill became the

defended acropolis. Here, excavations have

recovered finds dating as far back as the Early

Bronze Age; a possible Hittite city is still unat-

tested, however. Probably in the Hellenistic

period settlement expanded down the slope

of the hill, then, in late Hellenistic and Roman

times, to the south of the hill on slightly slop-

ing, almost flat ground. A wall surrounded

the town, built by the Seleucids in the third

century BC, supplemented by an enlargement

in the fourth century AD. Outside the walled

town lay a theater, built up against a nearby

hill, and a well-preserved stadium. Also out-

side was a Temple to Artemis, which accord-

ing to literary sources was the most famous

building of Perge. Despite much prospecting

in the region, it has not yet been found.

The city is divided by crossing streets into

four unequal areas (Figure 24.5), with city

blocks of different sizes. The main north–

south street, porticoed on both sides and with

a stone-lined watercourse down the middle,

runs from an elaborate nymphaeum (fountain

building) at the base of the acropolis (Figures

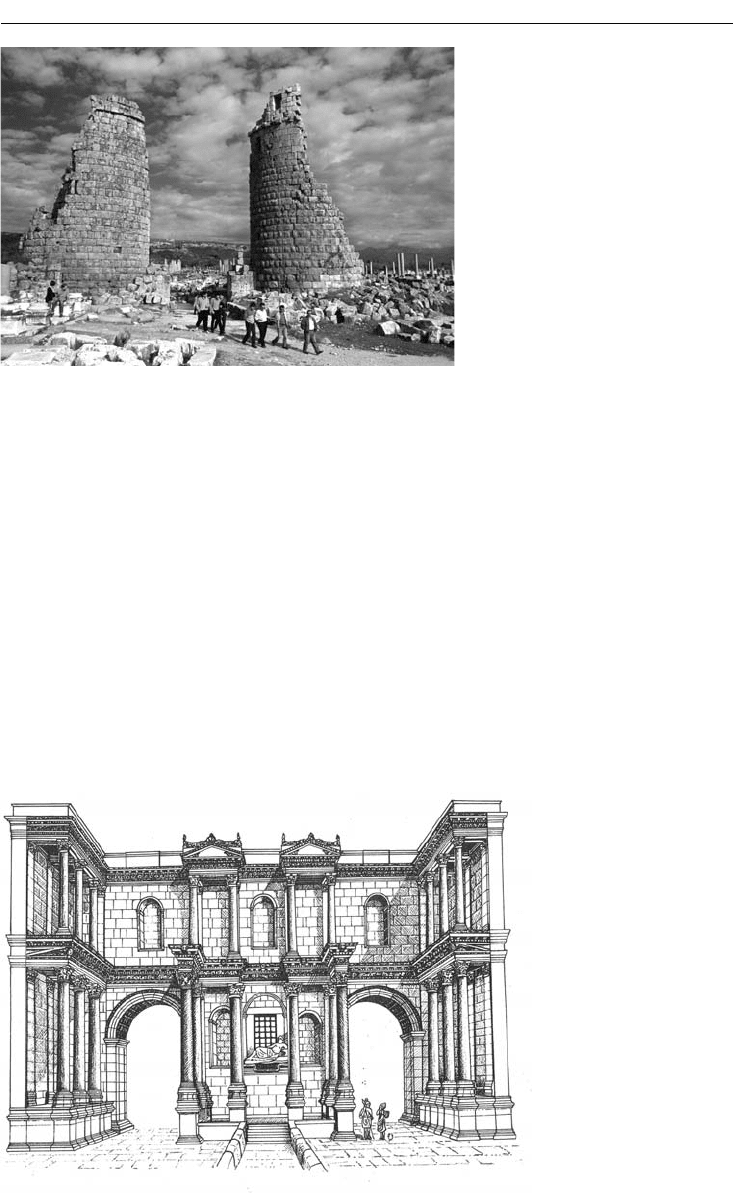

24.7 and 24.8) southward to the entrance gates. The Hellenistic gate is marked by a round tower

at either side (Figure 24.6). According to inscriptions, Plancia Magna renovated the gate, adding

its horseshoe-shaped court and a monumental triple archway at the north end of the court. The

interior walls of the court were lined with two levels of niches, seven above and below on each

side, each filled with a statue of a founder or prominent citizen of the city. Indeed, much sculp-

ture has been found at Perge, now on display in the Antalya Museum. Its local production was

substantial, although not rivaling that of Aphrodisias in the Maeander River valley to the north-

west, whose nearby marble quarries were exploited for an industry with a lively export trade.

PALMYRA

Palmyra, the “place of palms,” the Roman version of Tadmor, the old Semitic name, is located

at an oasis in the Syrian desert. Although occupied since prehistoric times, its early settlements

are poorly known. The city’s great prosperity and most surviving architecture date from the late

Hellenistic period to the late third century

AD. Especially in the second and third centuries, Pal-

myra grew rich from long-distance caravan trade, from its central position on an east–west trade

route between the Mediterranean coast and the Euphrates River and Mesopotamia. Political

Figure 24.5 City plan, Perge

400 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

conditions in the Near East made this route important at this time. To the south, the Nabataeans,

who earlier dominated trade from their capital city of Petra (in modern Jordan), were annexed by

the Romans in the early second century and lost their commercial ascendancy. In addition, Pal-

myra was well placed between long-standing rivals, the Romans and, to the east, the Parthians,

the rulers of Mesopotamia and Iran. Although the city belonged to the Romans, the Palmyrenes

were Semitic. Their culture was thus a blend of local Syrian with an admixture of Mediterranean

Greco-Roman elements.

The Romans took control of Palmyra some time in the first century. Hadrian visited in 129

with great celebration. The most dramatic episode in the city’s history occurred in the later third

century. After the Sassanian Persians (the successors of the Parthians) defeated and captured the

Roman emperor Valerian at Edessa in 260, Roman rule in Syria seemed to crumble. A Palmyrene

tribal leader, Odainat (Odaenathus, in Latin), stepped into the gap to protect his city’s interests.

He declared himself king of Palmyra, although remaining nominally a vassal of Rome. Acting as

Rome’s regional ally, he consolidated his position with victories over the Sassanians. His success

was short-lived: in 267 he was assassinated. His widow, Bat Zabbai (better known as Zenobia),

Figure 24.7 North nym-

phaeum (reconstruction),

Perge

Figure 24.6 South Gate, Hellenistic

period, Perge

ROMAN PROVINCIAL CITIES 401

took charge as regent for her infant son, and quickly put into motion an ambitious program of

conquest. Her armies captured Egypt and marched into Asia Minor. Then she proclaimed her

son Augustus, that is, a ruler independent of Rome. At this the Romans finally reacted. In 272,

the emperor Aurelian attacked and captured Palmyra, but spared the city. Zenobia, by most

accounts, was taken to Rome and displayed to the crowd in Aurelian’s triumphal procession; she

spent the rest of her life in comfortable detention in Tivoli, outside Rome. Soon after Aurelian’s

victory, the Palmyrenes massacred the occupying garrison; in revenge, the Romans sacked the

city. The city never recovered from this blow.

Palmyra is an extremely evocative site. The warm colored, intricately carved classical architec-

ture of this abandoned oasis city spreads out in the desert sands at the foot of a bare mountain

(Figure 24.9). From the seventeenth century, western travelers began to visit and write about the

ruins. Systematic exploration began in the late nineteenth century with a Russian team; German,

French, Swiss, Polish, and Syrian researchers have followed.

The architecture of Palmyra is, in general, Greco-Roman, but modifications were made by this

Semitic people with their own gods and their own customs. The main colonnaded street, with its

monumental arched gateway and tetrapylon, is firmly Roman; so too is the theater. Colonnaded

streets, gateways and theaters are architectural forms fulfilling functions found throughout the

Roman world, so the Roman architectural style comes as no surprise. Different in style, in con-

trast, are temples and tombs, building types that reflect local religious practices.

The major temple at Palmyra was consecrated to the Semitic god Bel. The cult on this site

must antedate the temple of the Roman period, for the orientation of the precinct and temple

differs from that of the central colonnaded street and the rough grid plan of the city proper.

Built in the first half of the first century, dedicated in 32, the Temple of Bel shows a remarkable

synthesis of Near Eastern and Greco-Roman forms (Figures 24.10 and 24.11). From the outside,

Figure 24.8 North nymphaeum, Perge