Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

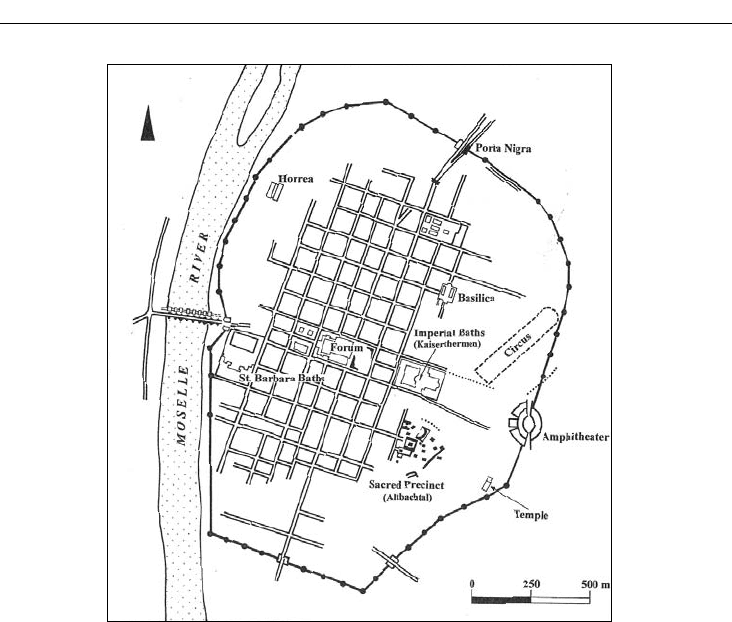

412 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

last served as a royal audience hall, originally part of a palace complex. Measuring 67m × 25m ×

33m, rectangular in form with a large apse at one end, this majestic building is the largest surviv-

ing hall from Roman times.

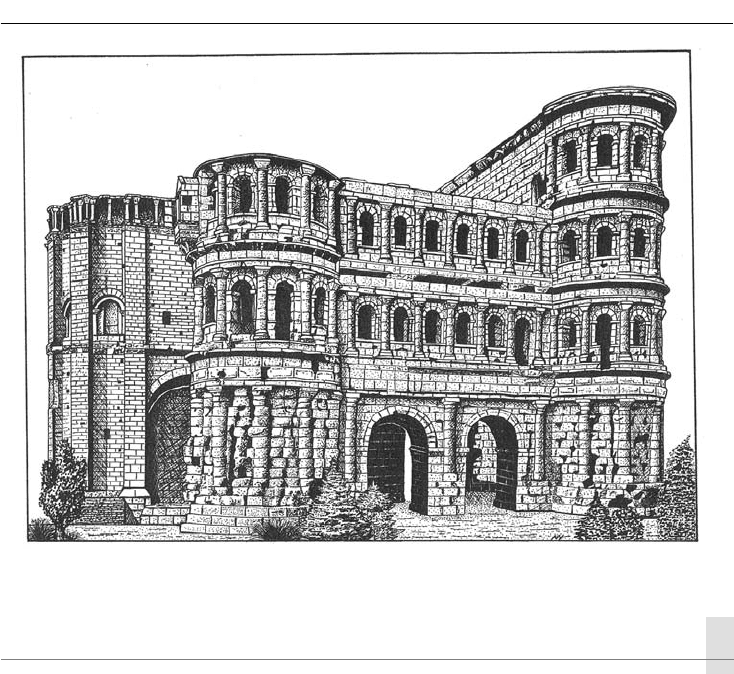

Particularly fascinating is the Porta Nigra, the distinctive north gate of Roman Trier, one of the

great surviving gate buildings from the western Empire (Figure 24.18). One of four main gates

built into the fortification wall, it is the only one still remaining. Its date is controversial; second,

late third, and early fourth centuries have been proposed, with a later date favored. The gate is

constructed of grey sandstone. The rough texture of the stone work was not deliberate, but an

indication that the building was never finished. Mortar was not used; instead, blocks were held in

place by iron clamps enveloped in lead sealings, to prevent rusting. The building today is pitted

with the holes cut by medieval people who sought the metal. Originally the Porta Nigra con-

sisted of two four-story towers flanking the passageway: a courtyard, enclosed by a double arch

on both the interior and the exterior sides. On the north, external side, the towers are curved,

almost semicircular; on the south, the façade is straight. All stories are decorated with columns;

in the upper three stories the columns flank arched openings. In medieval times, the Porta Nigra

was turned into a church. Among the many alterations done, an apse was added on the eastern

side and, to create a single prominent tower, on the west, the top floor of the eastern tower was

removed. Modern restoration of the building to its original function and appearance began under

the order of Napoleon in the early nineteenth century.

Figure 24.17 City plan, Trier (Augusta Treverorum)

ROMAN PROVINCIAL CITIES 413

CONCLUSIONS

This survey of provincial cities has emphasized selected themes, as noted at the beginning of the

chapter. To our fi nal question, what constitutes a Roman city, we can give an answer. There was

a certain uniformity of public building types, such as the colonnaded street, the forum, temples,

baths, a theater. Moreover, they were built in the Greco-Roman architectural style, although with

regional variations. In the eastern cities, cut stone is the preferred building material, not brick

and concrete; this choice results from the construction techniques established well before the

arrival of the Romans. In addition, and importantly, these cities display a predilection for a fi rm

framework in their layout, with a cardo and decumanus that cross, major streets that form the

main axes of the town plan. Often an orthogonal grid was added on top of that. Irregularities

were frequent, resulting from such factors as the exigencies of the local topography or from pre-

Roman plans. But the desire for a city-wide structure, greater than any individual concern, was

always present. This concept of urban planning owes much to the organization of the Roman

castrum. We have also seen the importance of imperial patronage, as well as the contributions

of wealthy men and occasionally women. The material well-being of one’s town was important

to support and protect in the fi rst through third centuries AD. So yes, we can indeed recognize a

Roman city, its physical appearance and the activities that went on in it, despite the regional dif-

ferences of geography, climate, religious practices, and ethnicity.

Figure 24.18 Porta Nigra, Trier

CHAPTER 25

Late antique transformations

Rome, Jerusalem, and Constantinople

in the age of Constantine

The age of Constantine the Great marks the end of antiquity and the beginning of the Middle

Ages, a new chapter in the history of the Mediterranean and Near East. Fascinating though they

are, the Middle Ages lie outside the scope of this book. This chapter presents some elements

that characterize this transformation, in particular features that have an impact on the chang-

ing appearance and functions of cities in the Mediterranean basin. We will end our journey in

Constantinople, for here, in this new capital city of the Roman Empire, both an ending and

a new beginning are most strongly felt (for places mentioned in this chapter, see the map,

Figure 23.1).

HISTORICAL SUMMARY

After the Severan dynasty, the Roman Empire entered a turbulent period, with great instabil-

ity at the top in the office of emperor. At the same time, threats from outside were increasing,

primarily from the Sassanian Persians on the east, and from Goths and other Germanic tribes of

northern Europe. In response to this, Aurelian had a defensive wall built around the capital (see

Figure 23.2). The Aurelian Wall, begun in 271, was Rome’s second fortification wall, following

the Servian Wall of the fourth century

BC. The new wall was 19km long, with 381 towers and

eighteen gates, and was made of concrete faced with brick, almost all reused, but with gates of

Selected Roman Emperors from the Severans to Constantine I:

Fifteen emperors (period of anarchy): 235–270

Aurelian: 270–275

Six emperors: 275–284

Diocletian: 284–305

Beginning of the Tetrarchy: 293

Constantine I (the Great): 306–337

Battle of Milvian Bridge: 312

Edict of Milan: 313

Foundation of Constantinople: 324

LATE ANTIQUE TRANSFORMATIONS 415

stone. The wall enclosed a much larger area than that of the Servian Wall; this reflects the growth

of the city in later Republican and imperial times. It was still in use in 1870, when the city was

captured from the papacy during the campaign to unify Italy. Much of it still survives.

Internal and external disintegration was staved off by Diocletian, who reigned from 284 to

305. He instituted important reforms, which included new laws, and a power-sharing scheme

known as the tetrarchy, whereby the two halves of the empire, the Latin-speaking west and the

Greek-speaking east, would each be governed by an emperor (the augustus) with an assistant (the

caesar). The two augusti would retire after twenty years, to be replaced by the caesars, who would

in turn select new assistants. Diocletian and his colleague Maximian I duly retired in 305, but then

the system collapsed because of the conflicting ambitions of their successors. War broke out

among the rivals. Primacy in the west was settled in 312 with the victory of Constantine I over

Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on the northern outskirts of Rome. After his defeat

of Licinius in 324 at Chalcedon (opposite Byzantium), Constantine I was left as the sole ruler of

the entire Roman Empire, both halves now integrated once again. But the unity was short lived.

The split between east and west continued to deepen. Constantine himself moved the imperial

capital eastward, from Rome to Byzantium, renamed Constantinople. After his death, the threats

from the north continued; in the fifth century, the western half of the empire was overrun by

the Germanic invaders. Goths sacked Rome in 410, the Vandals took North Africa in 439, the

Visigoths captured Spain and Portugal, and the Ostrogoths seized parts of Italy and the Bal-

kans. In 476 the last Roman emperor in the west resigned; even the fiction of a Roman rule was

finished. In the east, however, the Roman Empire continued until 1453. In modern times this

state has been commonly known as the Byzantine Empire.

In addition to the move of the capital, the reign of Constantine was notable for the entry of

Christianity into the public arena. At the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, Constantine allegedly saw

a vision of a cross, and heard a voice saying, “In this sign you will conquer.” Although his own

personal attitude toward Christianity is not known, some claiming he converted on his death-

bed, with the Edict of Milan of 313 he at least allowed Christianity the status of a legal religion.

By the late fourth century, during the reign of Theodosius I, Christianity would be proclaimed

the only legal religion. This change of religion is one symptom, although a major one, of numer-

ous changes in Roman society that took place in the fourth and fifth centuries.

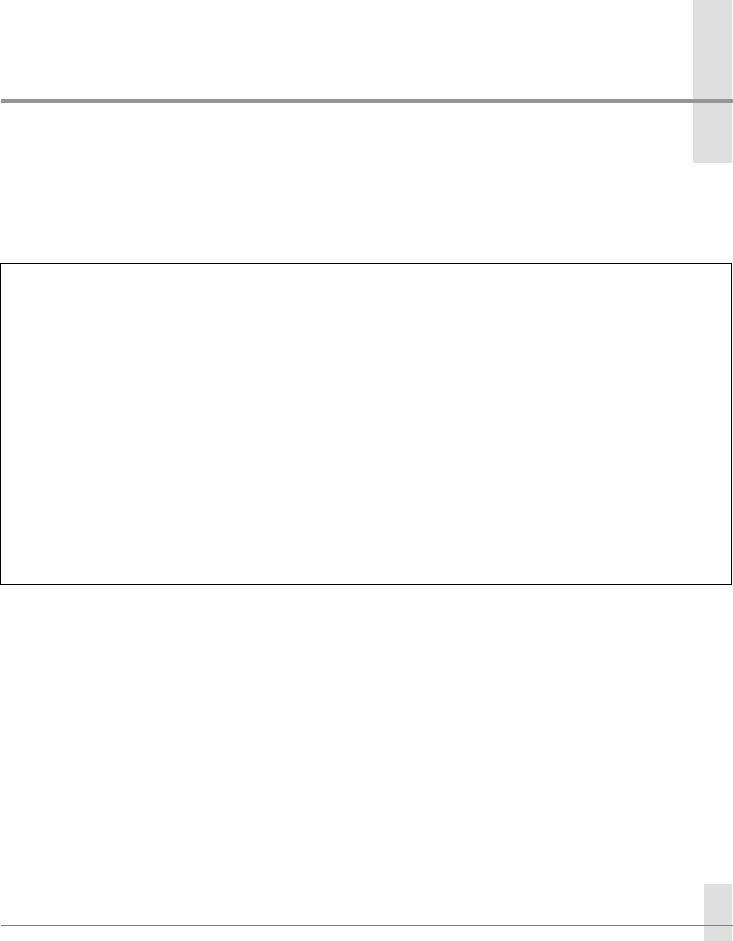

PALACES: PIAZZA ARMERINA AND THE PALACE

OF DIOCLETIAN

A good place to start to see the changes of this period is to contrast two palaces of the late third

to early fourth centuries. The Piazza Armerina in inland Sicily is a sprawling country villa that

recalls Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, whereas the Palace of Diocletian at Split (on Croatia’s Adriatic

coast) is a rigidly planned complex that recalls the Roman military camp, but with features that

will be taken up in future architecture.

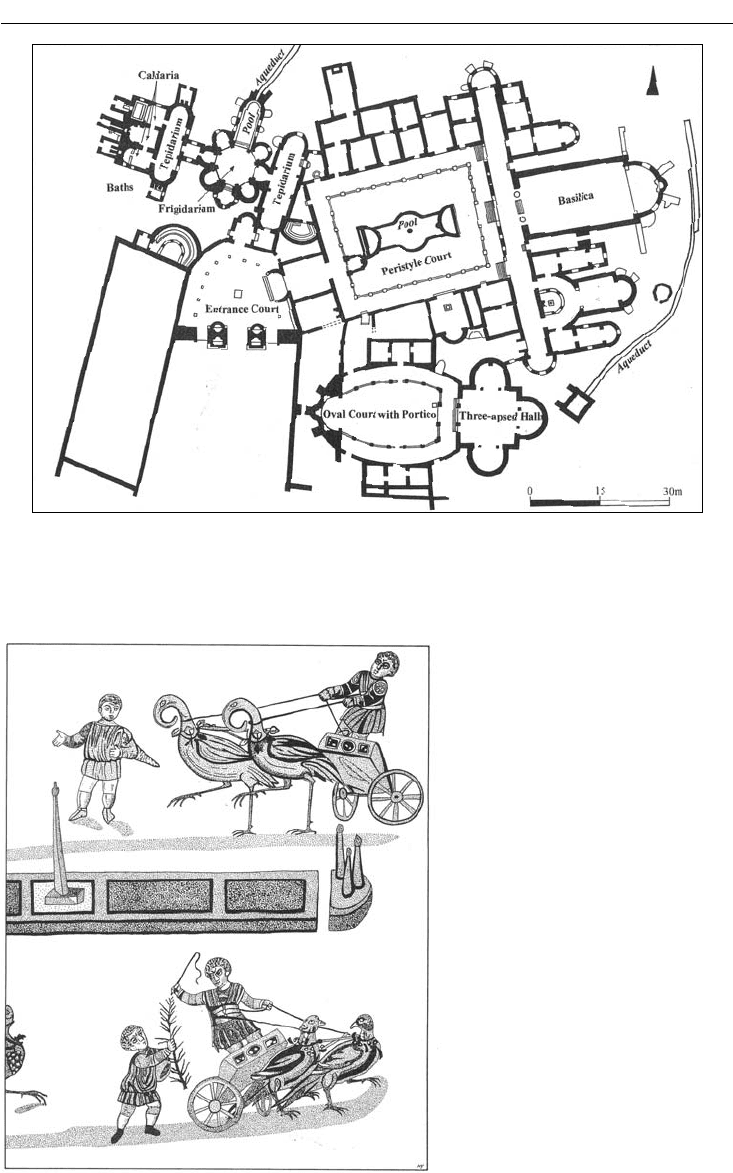

The Piazza Armerina was built in the early fourth century by an unknown person of distinc-

tion and wealth. This palace consists of a series of pavilions, placed in a tighter arrangement than

Hadrian’s Villa (Figure 25.1). It is famous for its many floor mosaics, covering approximately

3,000m

2

. Illustrated here is a comic chariot race, in which the chariots are pulled by flamingoes

and pigeons and ridden by boys (Figure 25.2). The style is late antique, and is an excellent exam-

ple of art of this period. Such floor mosaics will continue to be laid elsewhere, with a notable

sixth-century example in the Great Palace at Constantinople.

416 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Figure 25.1 Plan, Piazza Armerina

Figure 25.2 Mosaic from Piazza Armer-

ina (detail): comic chariot race

LATE ANTIQUE TRANSFORMATIONS 417

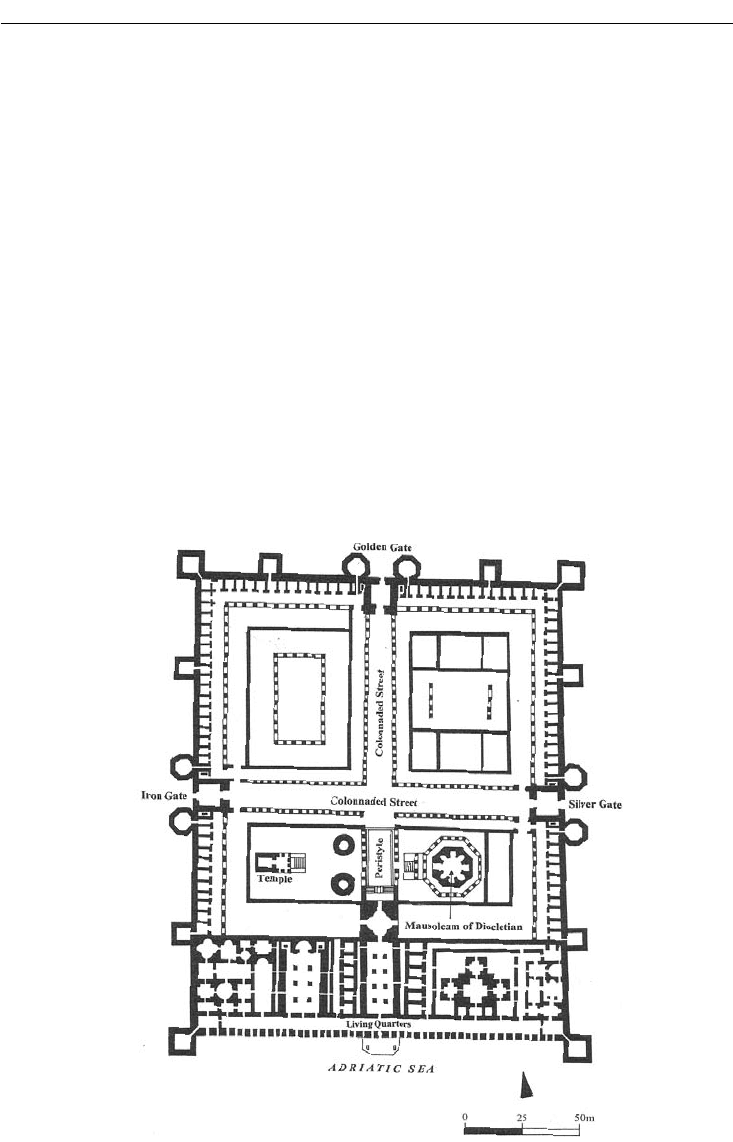

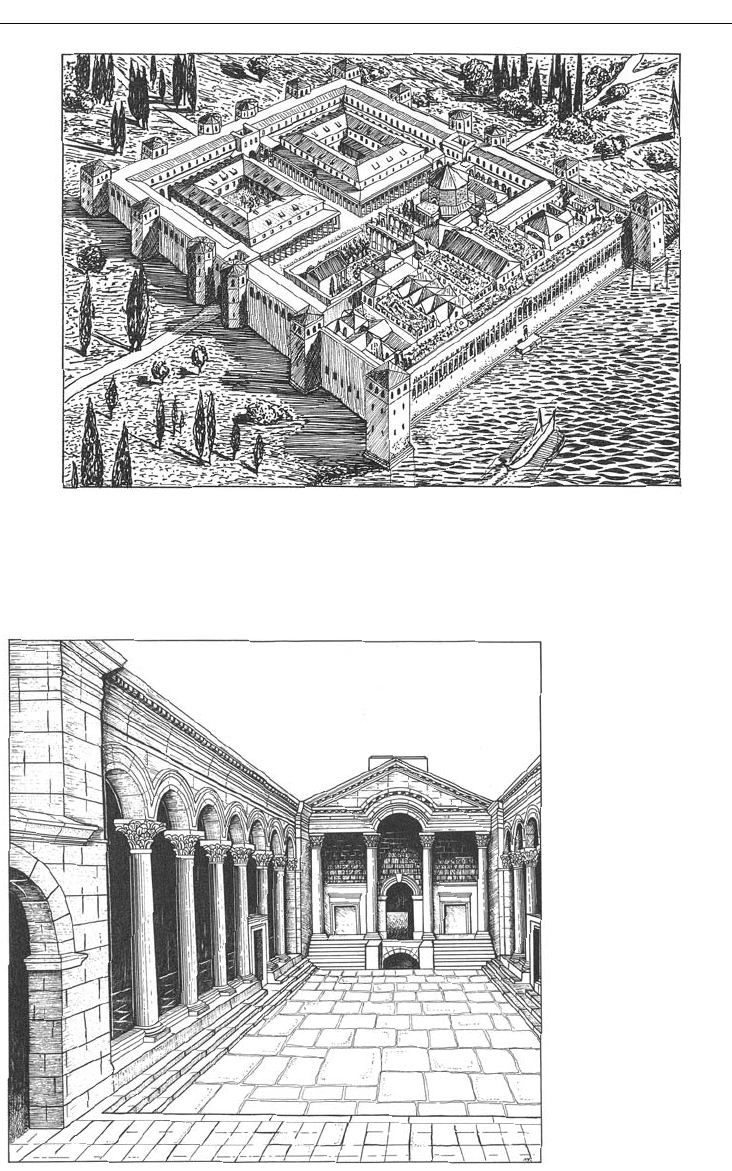

The Palace of Diocletian at Split offers a different synthesis of past and future (Figures 25.3 and

25.4). It was laid out in a near square, 175m and 181m × 216m, with fortified walls with square

and octagonal towers; inside, two main streets cross, like a cardo and decumanus. The feeling is

definitely that of a fortified military camp, a result perhaps of the uncertainty of the times, and so

Diocletian, who indeed included military leadership among his duties, honored a Roman principle

of planning developed many centuries before. Inside, however, certain features are characteristic

of the late third to early fourth centuries, not earlier. First, in one centrally placed peristyle court,

the porticoes are arcaded, with, at the rear, a Greek-type pediment combined with a Roman arch, a

favorite design of late Roman architecture (Figure 25.5). And second, the emperor’s mausoleum is

a building of the type known as the martyrium, a free-standing round or, as here, octagonal building

which would become the standard form for marking the burial of an important or saintly person or,

in Christian times, the site of a major religious event (such as the Nativity of Jesus).

Also included in this palace complex is a Golden Gate (Porta Aurea) on the north; Constan-

tinople will later have its own celebrated Golden Gate. A Temple of Jupiter with a barrel vault

lies symmetrically opposite the mausoleum, on the other side of the peristyle court. And on

the south side, a big rectangular hall with two additional halls to the west are among the recep-

tion rooms opening onto a sea-side gallery running the full length of the building (here labelled

“Living Quarter”). The rest of the palace is not well known, because of the alterations caused by

later rebuilding.

Figure 25.3 Plan, Diocletian’s Palace, Split

418 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Figure 25.4 Diocletian’s Palace (reconstruction), Split

Figure 25.5 Peristyle

Court, Diocletian’s

Palace

LATE ANTIQUE TRANSFORMATIONS 419

ROME

By the later third century, Rome was packed with buildings. What was still needed? How indeed

could an emperor make an architectural mark on the city as had, say, Augustus or Hadrian? Solu-

tions were found. Diocletian contributed a major bath complex, the largest yet built in Rome,

a development of the type seen in the Baths of Trajan. Constantine himself added a Basilica, or

rather completed a basilica begun by his rival, Maxentius, in the Forum Romanum. In addition,

Constantine constructed a triumphal arch adjacent to the Colosseum. This arch is of importance

for its sculptural decoration, a mixture of old and new. These three types – baths, basilica, and

triumphal arch – are all familiar from earlier Roman tradition, however. A new direction comes

in this period with the construction of the first public churches. Old St. Peter’s will serve as a

good example of this particular change.

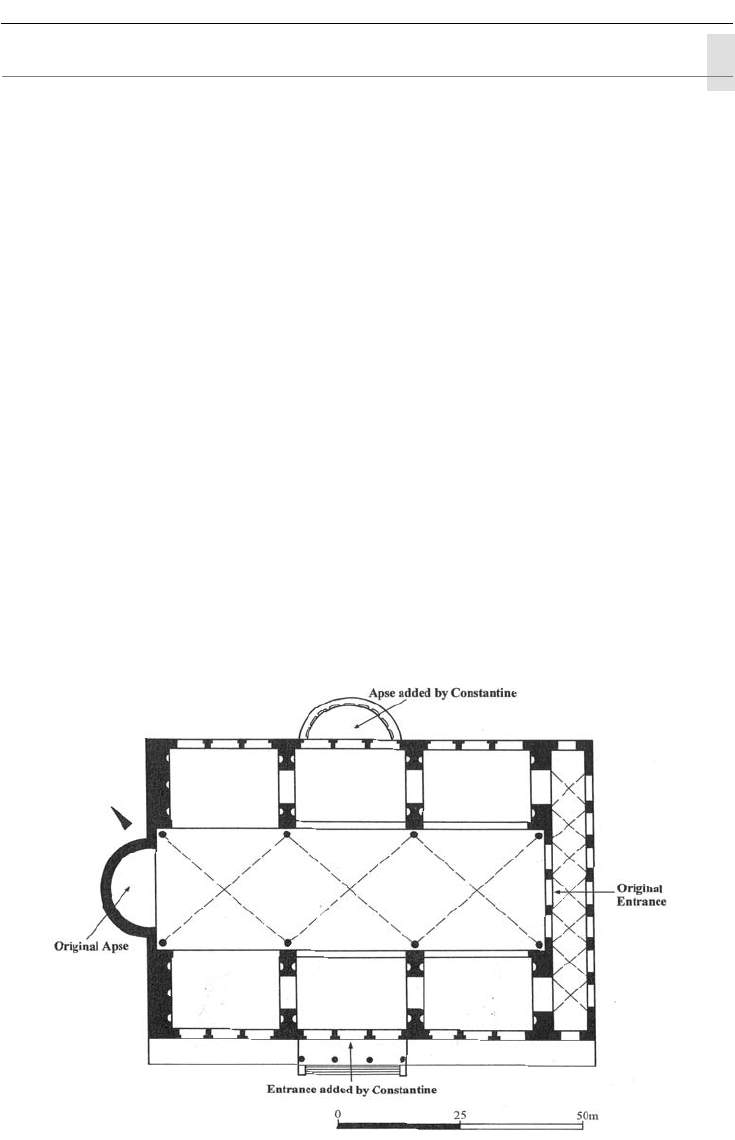

The Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine

This massive basilica, also called the New Basilica (Basilica Nova), was begun by Maxentius in

306–310 and finished by Constantine after 313 (Figure 25.6). It was erected in the Forum Roma-

num, on the north side (Figure 20.8). The building stands on a concrete platform 100m × 65m.

The nave is 80m long, 25m wide; its greatest height is 38m. Three bays on the north survive. The

nave has arcaded windows at the top, a sort of clerestory; concrete groin vaults in the ceiling; and

interior walls faced with red brick. The exterior of the basilica was covered with white stucco,

imitating masonry. Originally oriented east–west, Constantine changed this plan by placing an

apse on the north and stairs to the forum on the south.

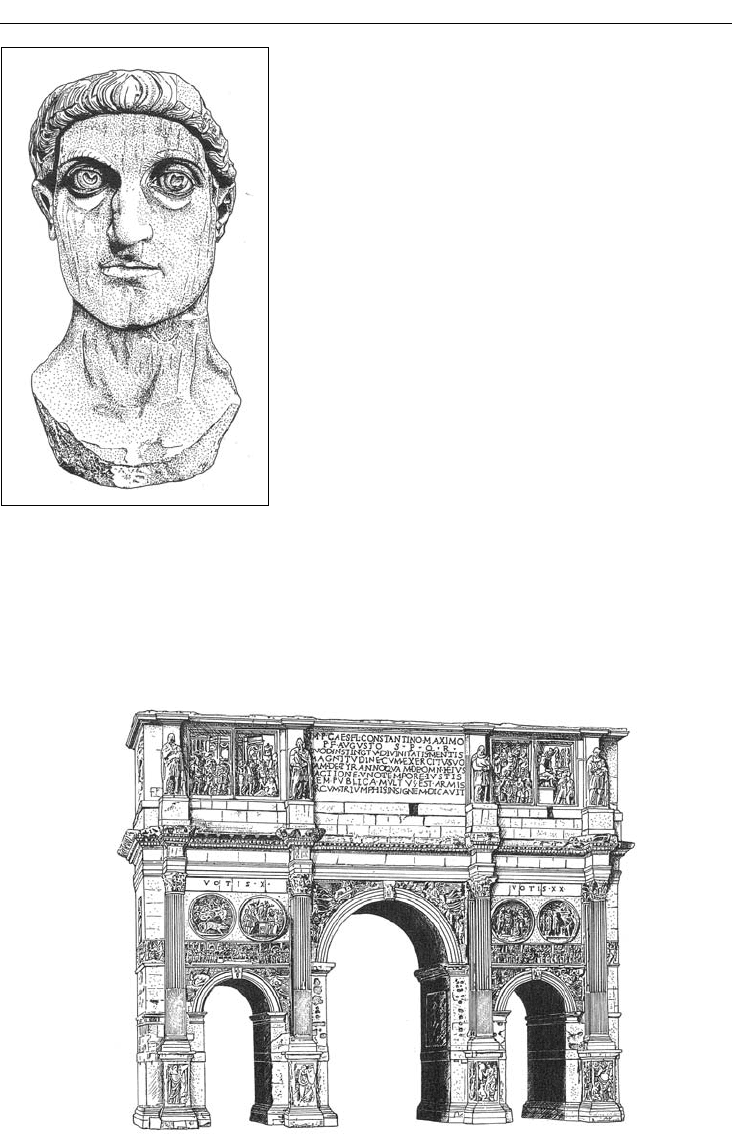

On a huge base in a west apse of the basilica stood a colossal seated statue of Constantine,

made in 324–330. Fragments were found in 1486. In a tradition going back to Near Eastern

Figure 25.6 Plan, Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine, Rome

420 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

practice, the statue was composed of different materi-

als: a brick core; the body of wood covered by bronze;

and the head and limbs made of Pentelic marble. The

head is 2.6m high, and weighs 8–9 tons (Figure 25.7). It

was joined with plaster to the neck. The emperor’s eyes

are slightly upturned; although the head is clearly from

the Greco-Roman style, the fixed gaze and upward turn

of the eyes projects us into the Middle Ages, when the

Christian emperor, considered an intermediary between

ordinary people and God, was depicted in an optically

non-realistic manner.

The Arch of Constantine

The Arch of Constantine has been called the “Gateway to

the Middle Ages” by modern art historians because of its

frieze, among the earliest examples of the medieval style

on a prominent imperial monument. Built in 312–315 to

commemorate Constantine’s victory over Maxentius, and

to celebrate his co-rule with Licinius, the arch has three

arched passages, the central being the largest (Figure 25.8).

The arch is noteworthy for its eclectic mix of sculptural

decoration. Panels were taken from monuments of the

second century, roundels from the Hadrianic period, rect-

angular plaques from the period of Marcus Aurelius, and stuck on in the attic of the arch. Such

reused stone sculpture and architectural members are known as spolia. In the Middle Ages, Greek

Figure 25.7 Constantine the Great,

colossal marble sculpture. Capitoline

Museums, Rome

Figure 25.8 Arch of Constantine (north side), Rome

LATE ANTIQUE TRANSFORMATIONS 421

and Roman buildings, destroyed or neglected, were excellent sources of building material for

new construction; spolia were sometimes used for decorative effect.

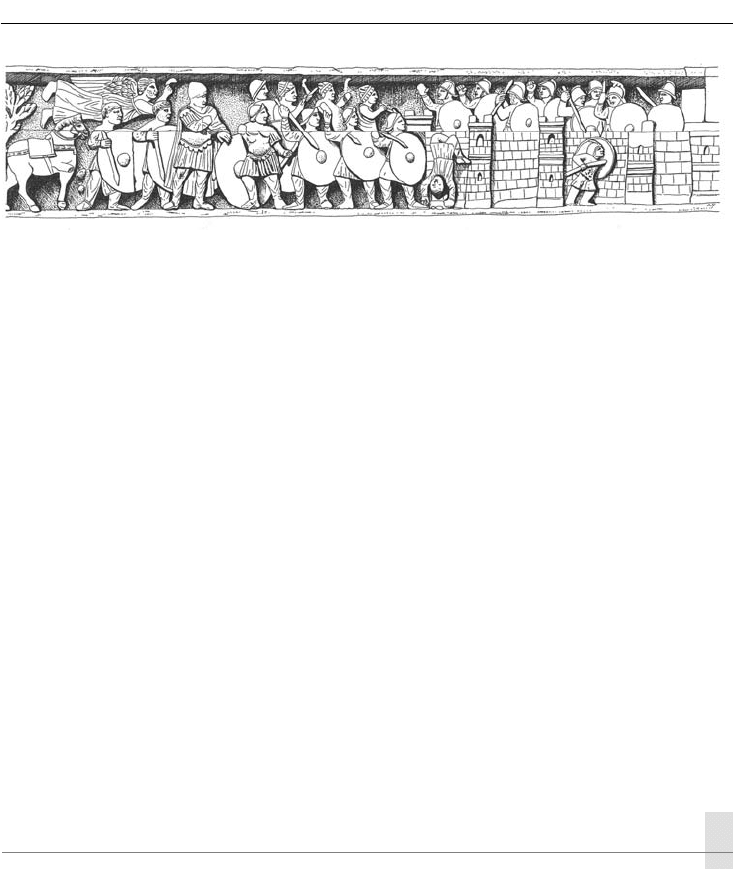

Contemporary with the building of the Arch of Constantine, however, are the friezes just

above the side arches. The frieze, in six panels on all four sides of the monument, recount the

campaign of Constantine, from his departure from Milan to the Siege of Verona (Figure 25.9),

the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, and his addressing the Roman people in the Forum Romanum

and distributing money. While the second-century sculpture is pure classical in style, with opti-

cally realistic views of the human body in action, the frieze is rigid, formally laid out with the

emperor in the center. In addition, squat body proportions are used, and people are not shown

as individuals, but as types. For observers since the Renaissance, it has been surprising that

an emperor would choose to reject the Classical style (esteemed by western Europe since the

Renaissance) in favor of what was judged an inferior medieval style. For medieval is in fact what

this style is, and there is no doubt that it was sanctioned from on high. Why? The breakdown

of the Classical style and the adoption of the medieval style is a great moment in the history of

European art. Its explanation is not evident, but must be due to many factors at work throughout

the vast empire. The change was not abrupt, and indeed Greco-Roman art continued to exert

influence, to varying extents, throughout the Middle Ages. Apparently art was changing in order

to reflect a new hierarchical concept of society, with the emperor firmly on top, others fixed in

their particular ranks and professions. These friezes fulfill the mission of visually explaining the

status of societal groups; optical realism was no longer sought.

CHURCHES

Directly following the Edict of Milan in 313, Christian churches began to be built in the open.

The first major church in Rome was St. John Lateran (later much rebuilt), located on the edge of

the capital, thus well away from the heart of the city and its important shrines such as the Capi-

tolium and the Pantheon. Another shrine had already developed on the west bank of the Tiber

at the tomb of St. Peter. In the early fourth century, a major church was erected on this site. This

was the Old St. Peter’s. It would stand for over 1,000 years until demolished in the early sixteenth

century in order to be replaced by an even more magnificent church, the Renaissance-Baroque

St. Peter’s cathedral still in use today.

Rome: Old St. Peter’s

Old St. Peter’s makes clear a key development in early church architecture: an already

existing architectural type, the basilica, a civic building, was adapted for use as a religious

Figure 25.9 Siege of Verona, relief sculpture, south-west frieze, Arch of Constantine