Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

352 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Corinthian order establishing the Greek tone, the temple also showed traditional Italic features

such as the high platform on which it stood and its frontality, with a broad flight of steps leading

up to the porch.

Dio Cassius, a senator and historian of the late second to early third centuries AD, gave a detailed

list of the activities that took place in this forum. Noted especially as the center for administration

of the provinces, the Forum of Augustus was also the place where boys formally put on the toga,

symbol of manhood; commanders sent abroad began their missions; and the Senate voted triumphs

to victorious generals, and where those same victors paid homage to Mars, god of war, by dedicating

to him their crown and sceptor of victory and captured military standards.

This forum was appropriately decorated with allusions, in sculpture, to the illustrious past

of the Roman state. Subjects were carefully chosen for their symbolic value in this space so

important for functions of the state. In the prominent large niche in each of the hemicycles

stood statues that combined references to the founders of the Latin nation and of Rome itself:

on the west, Aeneas carrying his father and leading his son out of burning Troy, and on the east,

Romulus, bearing on his shoulders the trophy from the first Roman victory in the 750s BC. Other

niches were filled with statues of important people, such as members of the Julian family, and

perhaps a colossal statue of Augustus. Only a few fragments of these statues survive.

Inside the temple, the cult statues were apparently three: Mars, of course, fully armed as the

Avenger, but with him Venus with Cupid (on his right) and the divine Julius Caesar (to his left).

The pediment displayed similar figures.

Above the Corinthian colonnade sixty-two caryatids supported a second story, smaller-scale

copies of the caryatids from the Erechtheion on the Athenian acropolis. For the Romans these

caryatids were not merely decorative. According to Vitruvius, they represented defeated peoples,

subjected in order to bring about peace. Between the caryatids were shields decorated with the

heads of gods. Horned Jupiter heads, perhaps Jupiter Ammon, an important syncretistic deity of

Egypt, may refer to the Roman capture of Egypt.

Ara Pacis

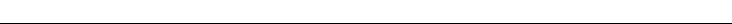

The last of the great architectural monuments from the city of Rome during the reign of Augustus

is the Ara Pacis Augustae, the Altar of Augustan Peace, a modest-sized (ca. 10m

2

) free-standing

altar designed for sacrifices to the goddess Pax, or Peace (Figure 21.4). Voted by the Senate in 13

BC, then built on the Campus Martius along a main thoroughfare, the Via Flaminia, the altar was

officially dedicated in 9 BC. The monument did not survive intact into modern times. Sculptural

pieces have turned up under the privately owned Palazzo Fiano since the sixteenth century, with

excavations carried out in 1903 and 1937–38. The altar was then reconstructed with the surviving

fragments, although not on its original location or orientation.

The altar proper lay inside an open-air space bounded by an enclosure wall, with entrances

on the west (main entrance) and the east. Relief sculpture decorated the entire monument,

with the figural scenes on the upper half of the outside of the precinct wall attracting most

attention. The monument commemorates the peace brought to the Roman state by Augustus,

and discreetly honors Augustus as a new founder of the city and state, a worthy successor of

Romulus and Aeneas. As we have seen, these themes, the bringing of peace and the linking of

the Augustan present with the legendary origins of the state, play an important role in the public

arts of Augustan Rome. The style of the sculpture is very much in the naturalistic tradition of

Greek art, a fact that reminds us that however Italic or Roman the subjects, a Greek manner of

presentation still mattered enormously.

ROME IN THE AGE OF AUGUSTUS 353

The east and west doorways were flanked by large relief panels with allegorical scenes

emphasizing the divine and heroic underpinnings of the Roman state. On the north-east side a

personification of the goddess Roma sits on a pile of armor. The message is clear: peace through

conquest, with Roma defeating her enemies in order to bring peace. On the left side is a well-

preserved (and partly restored) panel showing “Fruits of Peace.” A female personification of

plenty, variously identified as Mother Earth (Tellus), Venus, Italia, or Peace, holding two babies,

sits on a rock, surrounded by animals, plants, and fruits. On either side, nymph-like creatures

framed by billowing cloaks attest to peace on both land and sea. They ride animals: one woman

is on swan back, above an overturned jug, which represents the beginning of a spring, whereas

on the other side, we see a nymph on a rather frightening sea creature.

Beside the west entrance, the main entry to the altar, the fragmentary north-west panel shows

the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus. Mars, the boys’ father, and the shepherd who later

raised the children look on. On the better-preserved south-west panel, Aeneas, just landed in

Latium, pours a libation of thanks onto an altar. Two boys bring fruit and a sow for sacrifice.

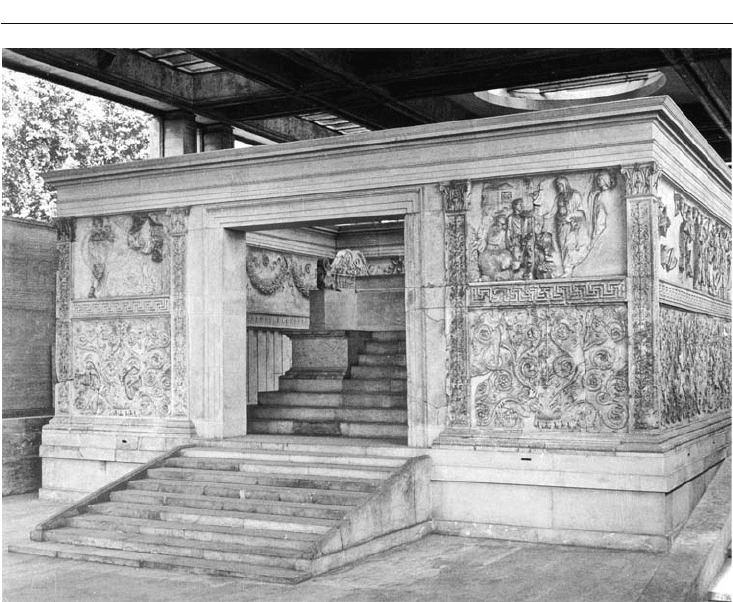

The south and north exteriors, again the upper half (the lower half being carved throughout

in elegant floral patterns), are decorated with a different kind of scene altogether. Here we see a

specific historical event: men, women, and children in procession, coming to celebrate the laying

of the foundation stone of the altar on July 4, 13 BC (Figure 21.5). Augustus walks among them,

in the center of the south side, but he is inconspicuous, as befitted the public persona he liked

to project. Also processing are officials, priests, and members of Augustus’s family, including

women and children, each person illustrated with a slightly different stance, movement, or

Figure 21.4 Ara Pacis, Rome

354 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

expression. The scene is tranquil, calm, dignified. The style recalls that of the Parthenon frieze

from fifth-century BC Athens, with idealized naturalistic representations of people, but there

are significant differences. Although the Parthenon frieze also shows a religious procession, it

is generalized; it does not show a particular procession in a specific year. Moreover, its cast of

characters differs: horseback riders, animals brought for sacrifice, and gods in attendance – but

not the Athenian political leadership. In another series of processional images that we have seen,

the reliefs of Achaemenid Persepolis (Chapter 10), the overall calm, harmonious tone matches

that of the Ara Pacis. But at Persepolis the processors bear tribute; the king awaits, seated, to

receive it. The smooth functioning of the empire is emphasized, but so, too, is the distinction

between ruler and ruled. Augustus, in contrast, hides his rulership, instead taking his place among

the many functionaries who together embody the Roman state.

The message imparted by the Ara Pacis procession is the orderly, beneficial rule of Augustus

and his family. With such other pictorial vehicles for ideology as the mythological panels on

the east and west sides of the Ara Pacis and the sculpture of the Forum of Augustus, and the

lesson proclaimed by his discreet house carefully located on the Palatine Hill, Augustus could

feel confident that public art and architecture in the capital city contributed fully to the new

chapter in Roman history: the end of decades of civil war and the renewal of the Roman state.

Figure 21.5 Procession frieze (detail), Ara Pacis, Rome

ROME IN THE AGE OF AUGUSTUS 355

Legitimacy stressed by connections with the key gods and heroes of the Roman people; his

own achievements made clear, never for his own glory, but always, really, for the stability and

prosperity of the Roman state – these themes Augustus made basic to his concept of rule. There

is something very Greek about this – fifth-century BC Athenian, that is. Augustus’s successors,

as we shall see, will continue to adorn the city with great monuments. But in a Hellenistic rather

than Periklean manner they will offer themselves the grandeur, private as well as public, that they

considered appropriate to their imperial status.

CHAPTER 22

Italy outside the capital

Pompeii and Ostia

Let us leave Rome for the moment and visit two cities where archaeological excavations have

given valuable information about ancient Roman town life that complements what we have

learned from the capital city. Pompeii was a modest-sized farming city located near Naples.

Developed during the Republic, it was destroyed in the early Empire by the eruption of the

volcano Vesuvius. Ostia, Rome’s port city, prospered from the Republic into the late Empire.

Because of the extensive preservation of their ruins, these two towns count among the richest

archaeological sites of Roman Italy.

POMPEII

Pompeii occupies a special place in Roman archaeology, for this city and its neighbors, notably

Herculaneum, were remarkably well preserved under the volcanic debris that rained down from

Mt. Vesuvius in AD 79. The ruins give an unequalled glimpse of the daily life of town dwellers

during the late Republic and early Empire. In contrast, in Rome itself, because of continuing

rebuilding throughout the Empire, remains from these periods are only sporadically preserved.

Explorations began at Herculaneum in 1732 and at Pompeii in 1748 under government patron-

age of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the first major archaeological excavations on a Classical

site. At first, methods were primitive; only in the 1860s, under the direction of Giuseppe Fiorelli,

did investigations take on a systematic form. Excavations have continued ever since, with most

of Pompeii now uncovered.

Historical introduction

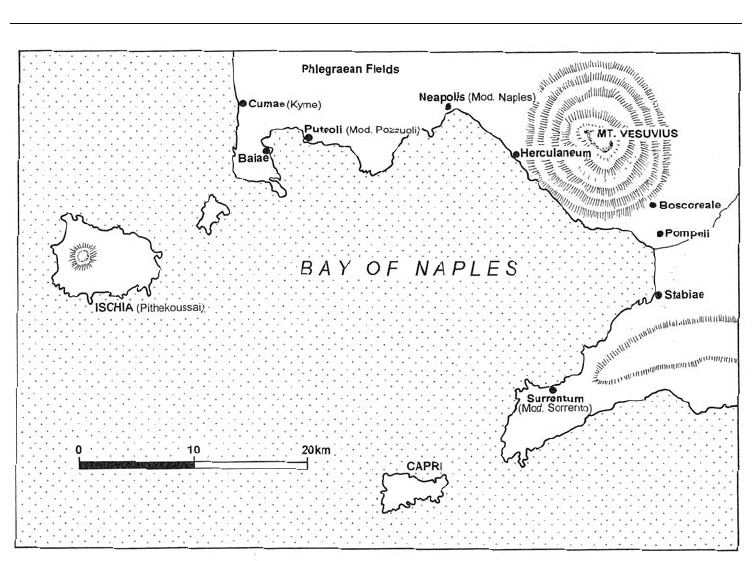

Pompeii is located on the Bay of Naples south of the city of Naples (Figure 22.1). The town lay

well sited close to the sea at a crossroads point where an important route to the interior branched

off from the coast road. The larger region of Campania and the Bay of Naples had already seen

much development by the time Pompeii was first settled in the sixth century BC. Greeks had

established themselves at the north end of the bay two centuries earlier, first at Pithekoussai on

the island of Ischia, then at Kyme (later Cumae) on the mainland opposite. A late sixth-century

BC Doric temple in the Triangular Forum records their influence in early Pompeii. Etruscans

expanded into Campania in the sixth century BC, only to be expelled by the Greeks in 474 BC;

finds of Etruscan pottery in deep soundings excavated below Pompeii’s main forum attest to

their contacts with the town. By the fifth century BC, Pompeii was the preserve of the Samnites,

a local people related to the Latins. But the Romans were expanding, and in 290

BC they defeated

the Samnites and took control of Campania. Pompeii remained ethnically Samnite, however. In

POMPEII AND OSTIA 357

the 80s BC, Pompeii joined other Campanian cities in the “Social War,” an unsuccessful uprising

against Roman domination. In the aftermath of his victory, the Roman general Sulla established a

veterans’ colony in Pompeii, with his veterans displacing local Samnite notables. The Romaniza-

tion of the city was now complete.

During the first century AD Pompeii prospered as a commercial and farming center, with a

population of 10,000–20,000. Its chief commodities included wool, flowers and perfume, and

garum, a highly prized fish sauce made of fermented sardine entrails. In AD 62 Nature struck a

first blow with a damaging earthquake. Then in the year 79, on August 24, Vesuvius erupted

without warning, spewing forth pumice, stone, poisonous gases, ash, and mud. Most people

escaped, but some were trapped; the forms of their bodies would be preserved in the volcanic

matrix long after flesh and bone had disintegrated. A letter written some thirty years later by

Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus describes the catastrophe, recounting how Pliny’s

uncle, Pliny the Elder, met his death. Pompeii and Herculaneum were largely covered, Pompeii

by 4m of pumice and ash, Herculaneum by up to 16m of volcanic mud. Salvage and looting went

on, and possibly even sporadic occupation at Pompeii, but full-scale reconstruction must have

seemed an impossible task. The ruined towns soon fell into oblivion.

Town plan

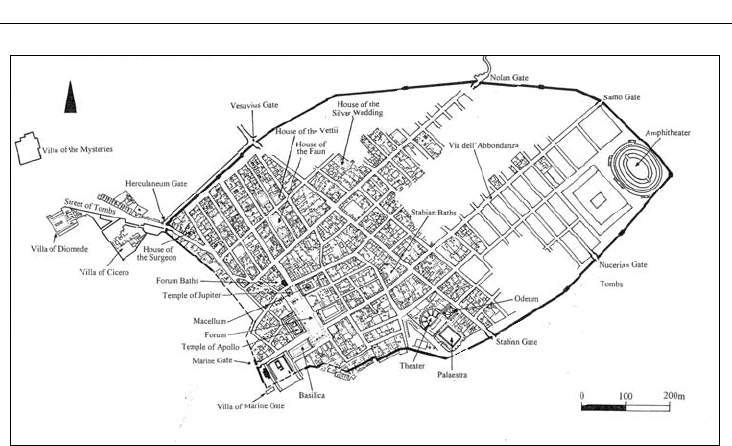

The early city lay in the south-west, a small area with irregular streets (Figure 22.2). The forum

lies within this sector. By the fourth century

BC the town expanded north of the forum, now

following a grid plan. City blocks in the north area contain some of Pompeii’s oldest surviving

Figure 22.1 Bay of Naples

358 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

houses. A circuit wall ca. 1200m × 720m was erected some time in the third century BC, enclosing

fields and gardens. Around 200 BC a further expansion took place toward the east. During the

second century BC, the last Samnite period, the town had two major north–south and east–west

streets; much building took place, including the theater, baths, and the portico that framed the

forum. The arrival of Sulla’s veterans stimulated a new building boom, with such structures as

the amphitheater and the odeum erected in the first century BC.

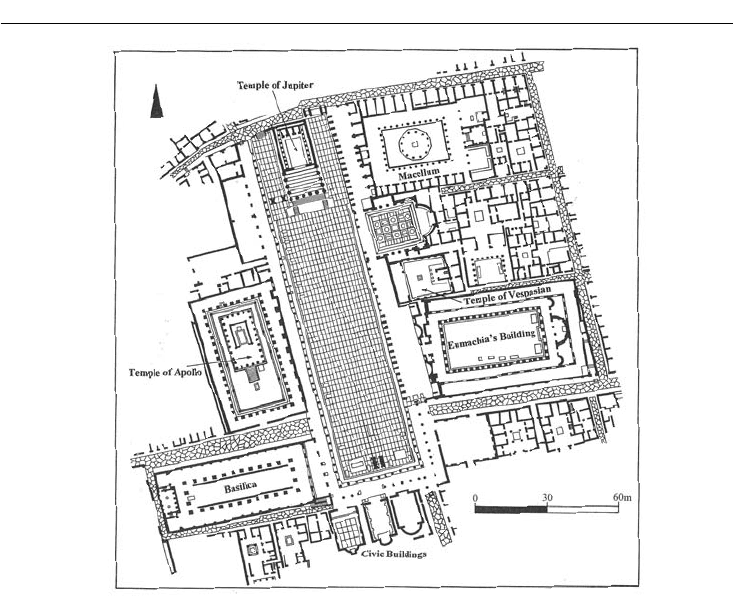

The Forum

The forum and its surrounding area contain the city’s most important group of public buildings

(Figure 22.3). The forum itself is a long (142m) and unusually narrow rectangular space. Origi-

nally colonnades lined the area, porticoes or covered walkways that hid most buildings behind in

the typical Hellenistic fashion already seen at Cosa. Prominently visible at the north, short end of

the forum, however, was the Temple of Jupiter. The temple was built in the second century BC in

the Italic style, on a high podium with steps in front, but with Corinthian columns. When Pom-

peii became Roman in the first century BC, the interior space of the temple was modified so that

Juno and Minerva could take their place alongside Jupiter. With the revered Roman triad now

installed, this central temple mirrored the venerable Capitolium of Rome itself – an important

connection with the capital city. The formality of the forum was further marked by the display of

statues of prominent citizens and by a prohibition on wheeled vehicles.

Behind the screen of the colonnades stood buildings that served a variety of religious, civic,

and commercial purposes. Connected with the forum were at least two temples in addition to the

Capitolium. A Temple of Apollo lies parallel to the forum, standing on a podium inside its own

colonnaded precinct. The temple uses Corinthian capitals, whereas the precinct features Ionic.

The cult of Apollo began as early as the sixth century

BC, as inscribed Etruscan vases attest, but

the temple was built later, in the second century BC.

Figure 22.2 City plan, Pompeii

POMPEII AND OSTIA 359

Across the forum, another temple honored the deified emperor Vespasian. Vespasian had

contributed to repairs after the earthquake of 62, and so was awarded this prominent place on

the east side of the forum. Emperors were routinely worshipped as divinities; the cult of the dei-

fied emperor served to link towns throughout the huge empire not only with the distant capital,

but also with each other.

Civic buildings occupied the south end of the forum. The Comitium met here. So too did the

duoviri, the chief magistrates of the town; the aediles, who policed the city; and the town council,

whose members were called the decuriones. On the south-west lies the basilica, placed at a right

angle to the forum. Built ca. 125 BC, this is the earliest preserved example of the type anywhere, a

large roofed hall (ca. 60m × 26m) with the higher-ceilinged central part allowing for a clerestory.

Its columns were made of baked brick, an unusual choice of material for the late Republic, but

covered with stucco in order to imitate more expensive stone. Ionic capitals were used on the

lower level, Corinthian above. This building housed many functions, such as law courts and

business activities.

Commerce was the purpose of the remaining major buildings that lined the east side of the

forum. The largest is Eumachia’s building (AD 14–37), a guild hall for the wool processors of

Pompeii. Eumachia, a wealthy woman, dedicated the building in the names of herself and her

son. Not being citizens, women could not participate directly in the political process, but their

public-minded gifts were always welcome. In the extreme north-east lies the macellum, a complex

containing the meat and fish markets and a small chapel to the imperial cult.

Figure 22.3 Plan, Forum, Pompeii

360 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Street life

Leaving the forum for other sectors of the town, the visitor has a wide choice of streets to follow.

The most impressive is today called the Via dell’Abbondanza. Like many other streets, it is paved

with lava blocks, has sidewalks and curbs and large stepping stones at intersections to get safely

over any mud or sewage. Shops were frequent. They include thermopolia, wine shops or snack

bars, with big clay storage jars embedded in the counter for easy serving of the beverages. Hot

wine was a great favorite. We can also see a mill and bakery, with stone mills for grinding flour

and an oven for baking bread. Street walls display advertisements for carpenters, politicians, and

gladiatorial shows, among others. Representations of phalloi are widespread, and have helped

identify brothels. Graffiti are everywhere. “Vote for Lucius Popidius Sabinus – his grandmother

worked hard for his last election and is pleased with the results,” reads one election appeal – or

humorous put-down. Sex and love are popular topics. “Fortunatus, you sweet little darling, you

great fornicator, this is written by someone who knows you!” reads one. Another, more serious:

“Noete, light of my life, goodbye, goodbye, for ever goodbye!” (Grant 1971: 208, 210).

Theaters and the amphitheater

Like all Roman towns of any size, Pompeii had its own theaters. The theater district lay in the

south part of the city. A large horseshoe-shaped theater was built in the Greek manner against a

natural slope; its date, late third or first half of the second centuries BC, places it earlier than any

surviving theater in Rome. The final remodeling took place in the Augustan period. In Roman

fashion, the stage building was connected with the seating, and the stage itself was placed low so

that important spectators sitting in the front rows could see well.

Next to the large theater is the odeum, a small roofed theater seating 1,000–1,500 people. It

was built ca. 80–75 BC, well after the large theater. The odeum (= Greek odeion) became a favorite

building type in the Roman world, a small hall for concerts and recitals, always covered, a useful

complement to the large open-air theater adapted from the ancient Greeks.

Behind the large theater lies a large square surrounded by a Doric colonnade, intended as a

shelter for spectators in case of rain and as a backstage area for the theater. By the time of the

city’s destruction this portico served as a barracks for gladiators, according to the finds: helmets,

armor, weapons, and related equipment, as well as graffiti referring to teams of gladiators. On the

east side of the colonnade, in excavations of 1767–68, skeletons of at least fifty-two people were

discovered, including children, and much jewelry. These people surely gathered here intending to

flee through the nearby Stabian Gate to the harbor, but died before they could escape.

Gladiators were the combatants in the brutal spectacles enjoyed by the Romans. Fights to the

death by armed men had distant origins in funeral rites of Etruscans and Campanians. By the

third and second centuries BC, such combats, detached from funerary contexts, became a stan-

dard part of public celebrations, often sponsored by a wealthy person. The popularity of such

entertainment continued unabated through the imperial period. Often originating as prisoners of

war, gladiators became true professionals, well-trained and well-equipped, because the rewards

for success could be enormous. The repertoire of combats expanded ever creatively. Gladiators

might face exotic wild animals imported from afar or unarmed criminals, already sentenced to

death. On the grand scale, mock battles were presented, even naval battles when an arena could

be filled with water.

The structure developed to present these spectacles was the amphitheater. The word means

“double theater,” and indeed the Roman amphitheater was completely round or oval. The

amphitheater at Pompeii, built ca. 80

BC in the south-east sector of the town, is one of the

POMPEII AND OSTIA 361

oldest surviving examples. Originally it was called not an amphitheater but “arena and spec-

tacula.” Arena meant the space, or sand, where the events took place, while spectacula meant the

viewing area where spectators sat. Pompeii’s amphitheater was unusual in being excavated into

the ground, its floor thus lying below ground level, its seating partially supported by earth yet

also rising above ground. Although the shows in amphitheaters were normally free, seating was

regulated according to social status, with important people in the best seats at the bottom, the

middle classes in the middle zones, and the poor – and perhaps most women – at the top.

The amphitheater seated 20,000, with spectators coming both from the city and from the sur-

rounding region. Indeed, the Roman historian Tacitus recorded a riot that erupted in the amphi-

theater in AD 59 between Pompeiians and fans from nearby Nuceria. The event is confirmed in

a Pompeiian wall painting that shows both amphitheater and fighting men. Because there were

deaths, the Roman Senate banned Pompeii from staging such spectacles for ten years.

Baths

By the time of the eruption, Pompeii had four large public bath complexes and many smaller

ones. Public baths were an important institution of the Roman world. Although some wealthy

houses had their own washing facilities, most people went to the public baths. The baths were not

simply for cleaning oneself, but were social centers where one exercised, relaxed, ate, attended

cultural events, and met friends and business associates. They generally opened at noon and

closed at sunset. Men and women had separate areas or, in small complexes, separate hours or

days. The grandest bath buildings were those of the capital city during the later empire. As one

would expect, the Pompeiian examples were more modest.

The origins of Roman bath complexes are disputed. Since many of the technical terms for

components of baths were Greek, the Romans may have taken much from the Hellenistic

Greeks. But local practices, such as taking advantage of the natural hot springs in Baiae, in Cam-

pania, surely contributed to the tradition.

The Stabian Baths, the earliest at Pompeii, were built originally in the second century BC,

later remodeled after 80 BC. The plan is irregular (Figure 22.4), but does include the key rooms

of the typical bath complex. One entered from the street into the changing room (apodyterium),

continued into a warm room (tepidarium), possibly a small sweat room (laconicum), and a hot room

(caldarium), then ended with a dip into a cold pool (frigidarium). The Stabian Baths also have a large

open-air swimming pool (natatio), a court for exercise (palaestra), smaller rooms, and a latrine.

Heating originally came from portable braziers, following Greek practice, but eventually the

warm and hot rooms were heated from below the floor. In this hypocaust system, the floors of

these rooms were raised on piles of bricks so that hot air from central furnaces could circulate

freely in the space below. Some bath complexes also contained walls fitted with flues for hot air,

a type of supplemental heating popular especially in the northern, colder areas of the empire, in

Germany, Gaul, and Britain.

Seneca, who lived above a bath establishment in first-century AD Rome, gives colorful tes-

timony about the crowded, lively, vibrant world of the baths. Rich men made grand entrances

accompanied by their servants; bath personnel circulated, offering equipment such as bath oil,

food such as cakes and sausages, and services such as plucking hair and giving massages; and

slaves operated the furnaces and kept the premises clean.

The Roman bath culture depended on the aqueducts bringing large quantities of water; main-

taining the aqueducts necessitated in turn economic and political stability. With the disruptions

of the Middle Ages, the system fell apart. In western Europe, the bath culture came to an end by