Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

342 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

begun by Julius Caesar in 44 BC. The Comitium, an officially consecrated open area, served as

the meeting area for the Comitia curiata. Originally without architectural form, it eventually was

given a fan shape, with steps. The rostra, the platform for speakers, originally stood here, but later

Augustus had a new set built at the north-west end of the forum. Rostra, a plural word, means

ships’ beaked prows. From the third century BC, the bronze battering rams of defeated warships

were displayed here. The Lapis Niger (black stone) is an area paved with black marble (in the time

of Caesar or Augustus) that covered earlier shrines, including, according to legend, the tomb of

Romulus. But no tombs have been discovered here, despite many artifacts from the early periods

of the city’s occupation.

Two covered halls lined the north and south sides of the forum, the Basilica Aemilia (or Basil-

ica Paulli) and the Basilica Julia. The Basilica Aemilia of 179 BC was the first in Rome, but it was

essentially rebuilt in 54–34 BC by L. Aemilius Paullus and his son, then restored by Augustus after

a fire of 13 BC, and again in AD 22. A row of shops gave onto the forum; passages led between

the shops into the basilica proper. Its central nave measured 82m × 16m, its two side aisles 7.5m

in width each. For Pliny the Elder, a prominent writer of the first century AD, this was one of

the most beautiful buildings in the city, due especially to its high-quality Phrygian marble. The

Basilica Julia, begun by Julius Caesar in 54 BC thanks to the spoils from his Gallic wars, finished

by Augustus, and refurbished after later fires, was built between the Temples of Castor and Sat-

urn, opposite the Basilica Aemilia. This basilica was used especially for banking.

The Tabularium, on the west side of the forum on the side of the Capitoline hill, is the best

preserved building from Republican Rome. Here the state archives were housed. An inscription

gives it date of construction, 78 BC, and records its patron, the consul Q. Lutatius Catulus, and its

architect, Lucius Cornelius. The plan is irregular and somewhat uncertain; it did have at least two

stories, the upper one being an arcade framed with Doric pilasters from which one had a good

view over the forum. During the Renaissance, modifications were made, the most important

being Michelangelo’s replacing of the ruined upper sections with the Palazzo del Senatore.

The Capitoline and Palatine Hills

The Roman Forum was bordered on the west and south by the Capitoline and Palatine Hills,

respectively. On the Capitoline stood the most important shrine of the city, the Temple of Jupi-

ter, while on the Palatine Hill, upper-class Romans had their city mansions. Also on the Palatine

was the Temple to Magna Mater, the great mother, built after 203 BC (consecrated in 191 BC),

but later burned and rebuilt. This shrine housed the sacred black stone of the Anatolian mother

goddess brought to Rome from Pessinus in central Anatolia, an early and famous example of the

syncretistic in-gathering of cults from the many peoples conquered by the Romans.

Outside the Roman Forum

Much is known about areas outside the Forum Romanum during the Republican period. In the

remainder of this chapter we shall visit markets, bridges, aqueducts, theaters, and the circus (see

Figure 20.1).

Markets

The main market area was located near the river. Important markets include the Forum Holito-

rium, a fruit and vegetable market; the Forum Boarium, the “cattle market,” a commercial area

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 343

crammed with shops and warehouses;

and the nearby Velabrum, a huge gen-

eral market. These market areas also

contained temples. Two are particu-

larly well preserved: one round, one

rectangular. The rectangular temple,

the Temple of Portunus, the god of

the ford in this place where in earliest

times the Tiber was crossed, is particu-

larly well preserved thanks to its trans-

formation into a church (Figure 20.9).

Built in the first century BC, it is a good

example of a Tuscan-type temple with

strong Greek influence. Tuscan ele-

ments include the high podium (2.3m

high) on which it sits; and its frontality,

marked by a broad flight of steps on the

front side and a deep front porch with

only engaged columns around the sides

and rear of the cella. Greek influence

includes the Ionic capitals and the shal-

low pediment. The “Portunium,” the

district around this temple, was a center

for flower and garland dealers.

An additional market hall stood somewhat to the south alongside the Tiber: the Porticus

Aemilia, built by two officials, the aediles M. Aemilius Lepidus and L. Aemilius Paullus, in 193

BC, with restoration in 174 BC. This long hall (487m × 60m) was one of a series of market halls

that served as distribution points for goods shipped on the river. In design it consisted of paral-

lel rows of linked barrel vaults, with arched openings in their long sides creating a large interior

space. The Porticus Aemilia was built of concrete, whereas others were wooden.

Bridges

Permanent bridges eventually spanned the Tiber; two are of particular interest for us. The Aemil-

ian Bridge (Pons Aemilius) was the first stone bridge, complementing wooden and pontoon

bridges; its piers, erected in 179 BC, were connected by arches in 142 BC. The bridge was partially

destroyed by floods in 1557 and 1598; in 1887 two of the three remaining arches were taken

down, leaving only one arch still surviving. The bridge is thus known today as the Ponte Rotto,

the Broken Bridge. To the north of the city lies the Milvian Bridge (Pons Mulvius); the important

road leading to the north, the Via Flaminia, crossed the Tiber here. The Via Flaminia was built

in 220 BC, but the stone version of the bridge arrived a century later in 109 BC. It was here in AD

312 that Constantine defeated his rival Maxentius, thereby securing his rule over the western half

of the Roman Empire.

Aqueducts

Aqueducts (Latin aqua, pl. aquae) were the channels by which water was brought to towns and

cities. Water flowed downwards, by gravity, from distant sources. Channels were normally

Figure 20.9 Temple of Portunus, Rome

344 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

underground but, if necessary, could be carried on arches. Rome would eventually be serviced by

many aqueducts. The oldest was the Aqua Appia, built in 312 BC by the censors Appius Claudius

Caecus (the paver of the Via Appia) and C. Plautius Venox. Most of its length (16km) from an

as yet unidentified spring lay underground. The Aqua Appia served low-lying areas, notably the

Forum Boarium. The longest of the city’s aqueducts was the Aqua Marcia, 91km in length, of

which 80km lay underground. It carried 187,000m

3

of water per day, a capacity exceeded only by

the Anio Novus aqueduct (190,000m

3

per day).

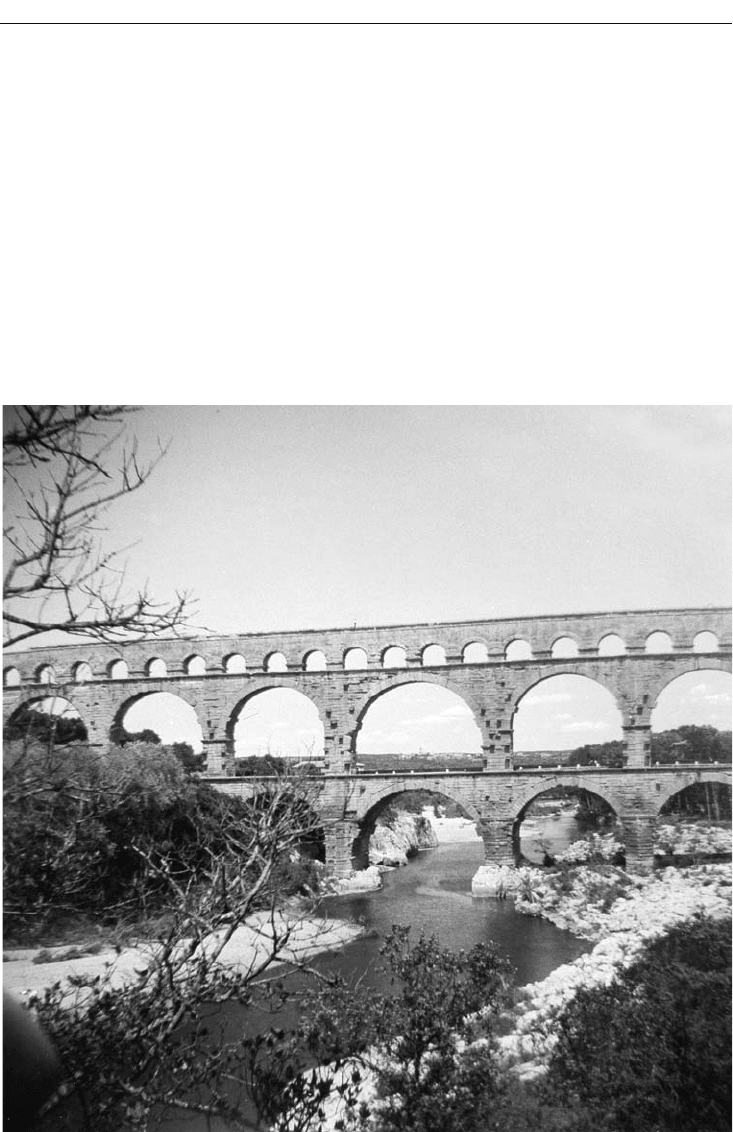

For a spectacular example of an aqueduct surviving from the immediately post-Republican

era, we turn to southern France, to the Pont du Gard of AD 14 (Figure 20.10). This bridge

was but one segment of an aqueduct that brought water from Uzès to the Roman town of

Nemausus (modern Nîmes). The level of the water channel slowly fell 18m over its length of

48km. Three stories and 54m high, the bridge carried the water channel, lined with hydraulic

Figure 20.10 Pont du Gard, France

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 345

cement, at its top, and thereby ensured that the carefully maintained level of the water

channel would not be interrupted by the river valley. Each story contained typical round Roman

arches, the uppermost level (with the water channel on top), the smallest, marked by the smallest

arches.

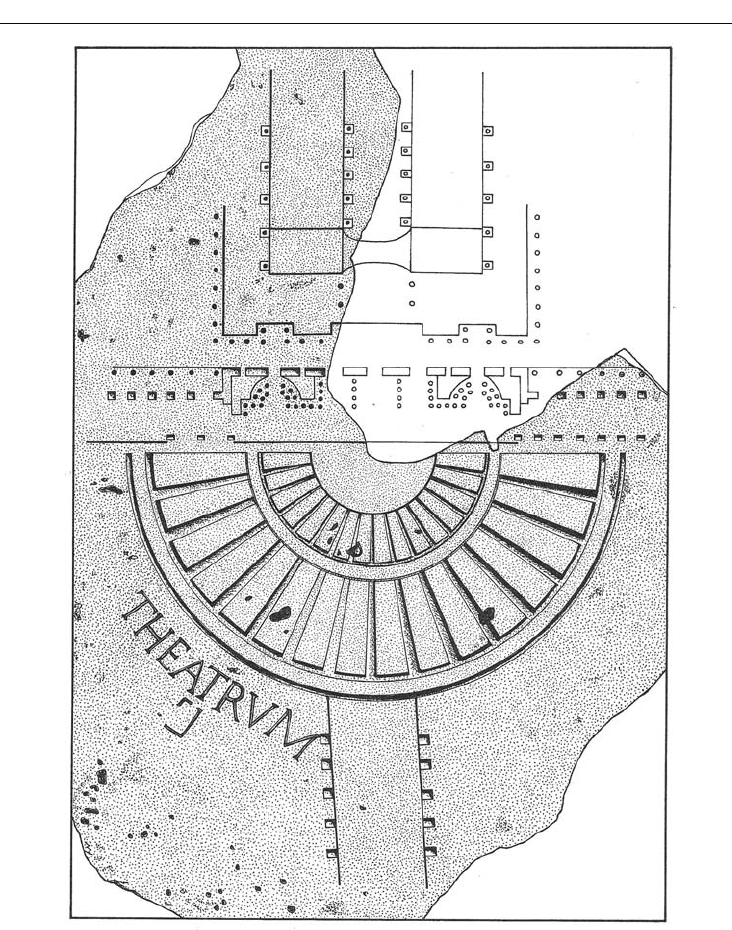

The Theater of Pompey and the Circus Maximus

Republican Rome also saw the building of theaters, under Greek influence, and formal structures

for amusement, notably the Circus Maximus. The early Theater of Pompey (55 BC) would remain

the city’s most important. The general Pompey, after winning victories in the eastern Mediterra-

nean, celebrated by building Rome’s first stone theater and an enclosed peristyle garden behind.

Although the theater was often rebuilt in antiquity, being much favored by emperors, only the

substructure of the cavea still remains; in addition, its contours are preserved in the modern

street plan of Rome. More details are known thanks to mentions in literary sources and to its

appearance in the surviving fragments of the Forma Urbis, a marble plan of the city carved in the

Severan period between AD 203 and 211 (Figure 20.11).

The theater is based on Greek models, since theater originated as a Greek practice. The-

aters of both wood and stone had already been in use in Italy, especially in southern areas

under more direct Greek influence. Although theatrical performances had originated in Greek

religious practice, evidently by the first century BC that association had diminished. Pompey

renewed this religious connection by having a Temple to Venus Victrix constructed at the top

of the cavea, facing the stage, and three, perhaps four, additional shrines. Subsequent Roman

theaters did not include such temples. Greek theaters were built on hillsides; this one was not,

but instead, profiting from Roman technological advances, was erected on vaults of concrete

faced in part with opus reticulatum. The plan departs from the typical Greek theater in hav-

ing a semicircular cavea. Seating is estimated at 11,000. But it still has open parodoi and a low

wide stage, probably made of wood but decorated with portrait sculpture. During the empire

Roman theaters would be much elaborated. The cavea and stage building were connected in

a single unified structure. Multi-story stage buildings, decorated with marble revetments, fea-

tured complex architectural frameworks of architraves and columns, creating niches for the

display of full-size statues.

The Circus Maximus, Rome’s oldest and largest track for horse racing events, was laid out

south of the Palatine Hill in the early Republic. The first starting gates, probably wooden but

painted in bright colors, are dated to 329 BC. The long narrow track was divided lengthwise

down the middle by the spina, at first only a natural stream that happened to run through this

area, but later elaborated with bridges and structures holding sculpture and such other monu-

ments as an obelisk of the Egyptian king Ramses II. Enlargement to its final size, 621m × 118m,

took place in the late Republic. Seating in permanent materials was eventually provided in the

lowest of the three cavea zones, first wooden seats, later stone. According to Pliny, maximum

capacity was 250,000, a number that indicates the huge popularity of the favorite event, races of

chariots drawn by four horses. Teams, or factions, were like modern professional sports teams,

with directors and patrons and full support staff as well as the racers themselves, and of course

followed by avid fan groups. A race normally consisted of seven laps around the spina; a full day

consisted of twenty-four races.

346 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Republican Rome: summary

Despite the fragmentary nature of the surviving evidence, we can nonetheless obtain a picture of

Republican Rome, especially in the second and first centuries

BC, as a prosperous city with devel-

oped religious, governmental, commercial, and leisure activities, with an infrastructure of roads,

bridges, sewage, and water circulation. The imperial period will continue the lines established

Figure 20.11 Theater of Pompey, shown on the Forma Urbis Romae

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 347

during the Republic, adding notably palaces, huge municipal bath complexes, and public com-

memorations in sculpture – all the result of the change in government and patronage of art and

architecture from oligarchy to monarchy. Important, too, will be the enlarging of the repertoire

of architectural forms, developments linked to the use of concrete. We turn first to the city of

Rome at the time of Augustus, the transition from Republic to Empire.

CHAPTER 21

Rome in the age of Augustus

The city of Rome was transformed during the reign of Augustus, the first of the Roman emperors.

Augustus understood uncannily well the impact that images, buildings, and materials could have

on the prestige of a city. He set a new standard for the physical world of the Roman city that

would continue for several centuries. Before we examine some of his building projects in Rome,

let us first look briefly at his life and at one famous image of him, with a view to identifying

elements that he considered important in the creation of the urban environment.

AUGUSTUS, THE FIRST OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS

Octavian, the grandnephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar, assumed complete control of

the Roman state after defeating Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.

Four years later, the Senate granted him the title Augustus, and it is under that name that we

know him best. Until his death in AD 14 he ruled the Roman Empire with enormous vision and

competence, bringing enduring peace and prosperity after decades of civil war. Interestingly, this

great ruler who understood so well the value of grandeur in the public arena cultivated a personal

life style of moderation, of deliberation, of self-control. Two sayings attributed to him by the late

first- to early second-century biographer Suetonius show clearly his outlook on life: a favorite

Greek proverb, “Make haste slowly” (reflecting his energy combined with deliberation) and, at

the end of his life, the remarkable words: “How does it look? Have I performed the comedy of

life properly?”

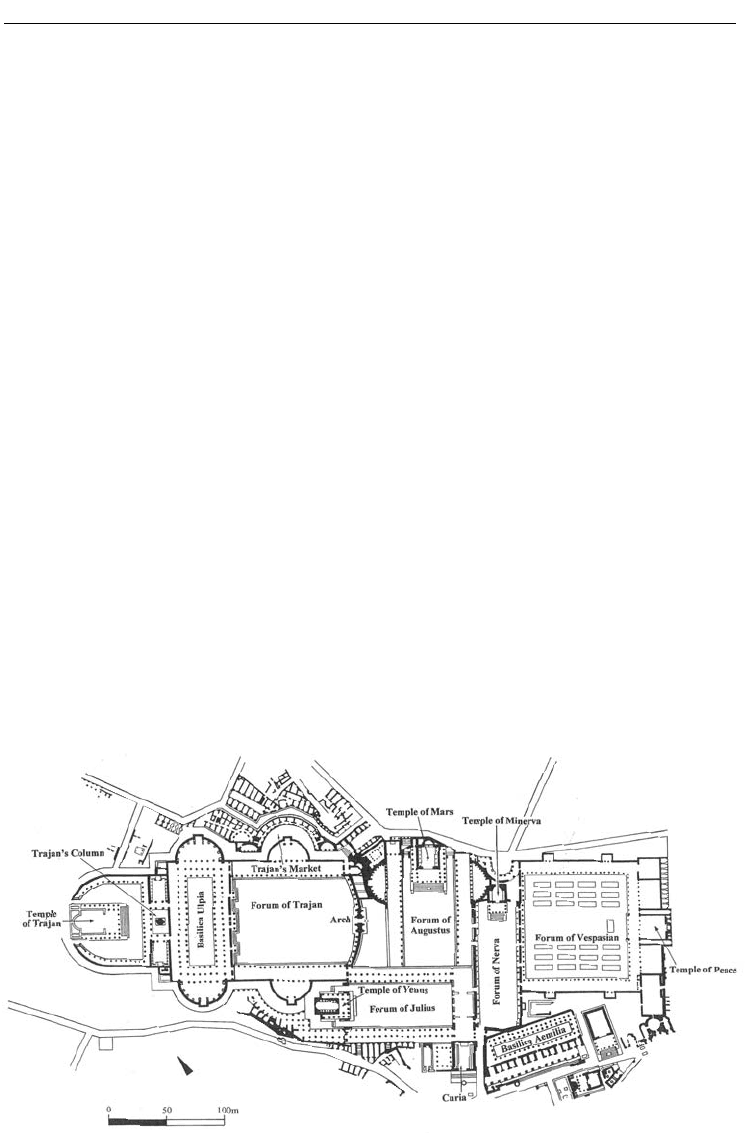

The Augustus of Primaporta

The majestic statue of Augustus from Primaporta brings to the fore his understanding of the

power of images (Figure 21.1). The work combines Greek and Roman features, idealized and

specific, a calculated blend that served as an official image of the emperor. The head portrays

Augustus as a young man. Following the realistic tradition of Etruscan and Roman portraiture,

the features appear specific, such as the broad skull and the narrow chin, and confirm Suetonius’s

description of Augustus as extremely handsome. This attractive, idealized face had become a

standard image, one that Augustus used until the end of his long life, in accordance with the

Greek view that portraits should function as types, not as optically faithful records.

Augustus born 63 BC; ruled 31 BC–AD 14

ROME IN THE AGE OF AUGUSTUS 349

With the body, however, the image departs from reality, for Suetonius described Augustus

as rather short, even if well-proportioned. The body reproduces the stance and the heavy

musculature of the “Doryphoros” of Polykleitos, a Greek work of the fifth century BC much

copied by the Romans, and so connects Augustus with the idealized heroic image that Greeks

projected in statues of nude athletes. But Augustus is clothed, even if the cuirass is revealingly

form-fitting. His military garb specifically identifies him as a soldier and recalls his personal

heroism on behalf of the Roman state. Further, the armor serves as a vehicle for details about

Augustus’s military achievements. Relief sculpture on the cuirass includes the depiction of a

Parthian returning captured standards to a Roman, a symbol of peace brought to the uneasy

eastern frontier of the Roman Empire.

The statue may be a marble copy of a bronze original made after the Romans retrieved their

standards in 20 BC. It was found in 1863 at Primaporta outside Rome in a villa that perhaps

belonged to Livia, Augustus’s wife; it may have stood outdoors as a garden decoration, as stone

statuary often did in Roman times.

AUGUSTUS AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF ROME

We return to the city of Rome itself with another declaration that Suetonius attributed to

Augustus, that he found the city made of brick and left it made of marble. Augustus realized the

importance of making the capital Rome into an architectural showcase for the world. As with the

other arts, his grand design featured the integration of Greek forms and materials with traditional

Figure 21.1 Augustus of Primaporta, marble statue

from Rome. Vatican Museums

350 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Italic features. Marble, a favorite Greek material heretofore imported into Rome, now became

familiar, thanks to the opening of an Italian source, the Carrara quarries of north-west Italy.

Among Augustus’s many architectural contributions, three buildings in particular illustrate his

approach to symbols, architecture, and the image of his own personality: the House of Augustus,

the Forum of Augustus, and the Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace). Let us begin with the simplest, the

House of Augustus.

The House of Augustus

For a ruler of such wealth and power, the house Augustus chose to live in was surprisingly

modest. It would not have been simple: a building of at least two stories, its rooms fairly small

but certainly well appointed. Wall paintings were of high quality, often showing architectural

scenes. But this was not the lavish palace preferred by many of his successors. For Augustus, this

moderation was important. Also significant was the symbolic value of its location. The house

stood on the Palatine Hill in a sector where modern archaeology has revealed remains of Iron

Age houses of earliest Rome. Indeed, one would have seen nearby a model of the House of

Romulus. The proximity allowed Augustus to connect symbolically with the legendary founder

of the city. Also adjacent to the house was the Temple of Apollo Palatinus; Apollo was credited

with giving Augustus key support in his victory at Actium. The house, already burned and rebuilt

in Augustus’s lifetime, seems to have been abandoned after his death and seriously damaged

during the great fire during the reign of Nero, in AD 64.

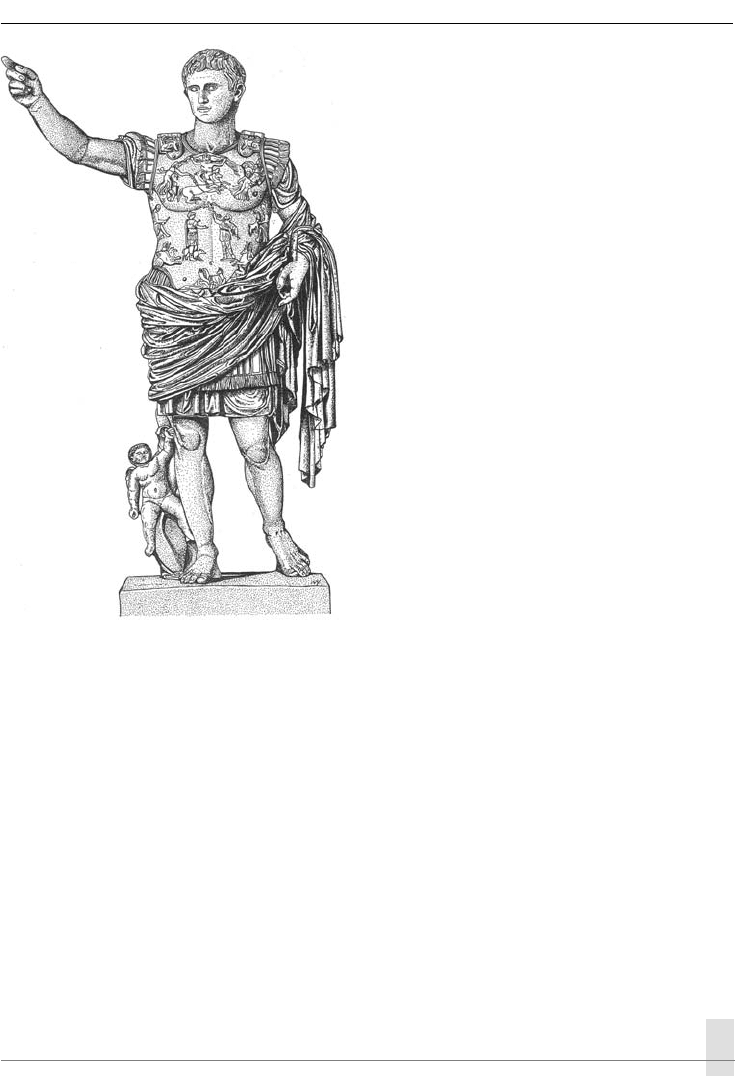

Imperial fora: the Forum of Julius and the Forum of Augustus

The greatest architectural complex in the city of Rome during this period was the Forum of

Augustus. In order to understand it, we must first backtrack to the Forum of Julius (Figure 21.2).

Julius Caesar, the dominant military and political leader from ca. 60 BC until his assassination

in 44 BC, was, like Augustus after him, active in improving the architecture and services of the

Figure 21.2 Plan, imperial fora, Rome

ROME IN THE AGE OF AUGUSTUS 351

capital. In 54 BC he commissioned a monumental public square to serve as an expansion of

the crowded Roman Forum. Because of its desirable downtown location, the land, purchased

from private owners, was extremely expensive. The resulting Forum of Julius consisted of an

open-air space lined with colonnades. A Temple of Venus Genetrix dominated the square. Julius

considered himself a descendent of Venus, the goddess of love. As the mother of Aeneas, the

Trojan hero and ancestor of the legendary founders of Rome, Venus was additionally venerated

as a special ancestress of the Roman state. Although a temple in a colonnaded court was a Greek

concept, the Greekness further emphasized by the use of marble as an elegant building material,

an Italic flavor was achieved by placing the temple on a high podium at one end of the space. The

temple was dedicated by Julius Caesar in 46 BC, but completed by Augustus. The Forum of Julius

was the first of a series of imperial fora, regular self-contained architectural units each planned

separately, all so different from the Roman Forum which had developed gradually and irregularly

over many centuries.

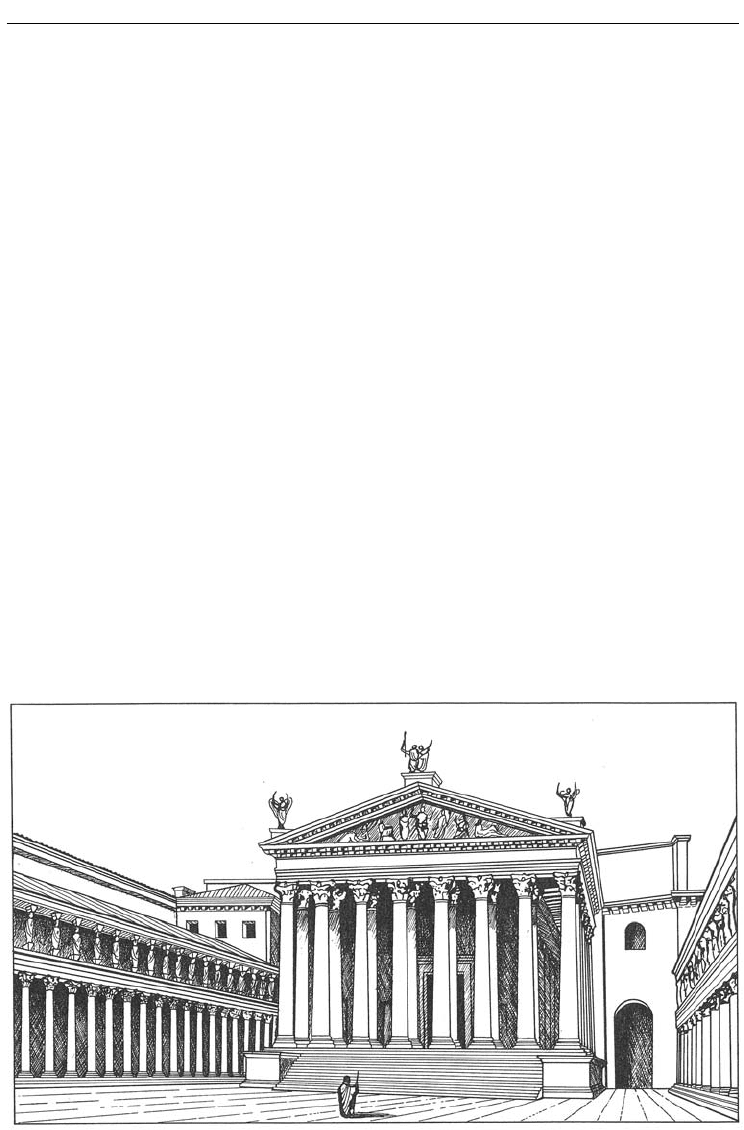

The Forum of Augustus builds on the concept of the Forum of Julius: a centrally located

civic complex that is monumental; civilized with its Hellenic decoration; connected with the

gods (by including a temple); and rich with symbolism important for the state. After his victory

over the assassins of Julius Caesar at the Battle of Philippi in northern Greece in 42 BC, Octavian

(later Augustus) vowed to build a temple to Mars the Avenger (Mars Ultor). The Forum of

Augustus would be the frame for the new temple. Work on the forum probably had begun by

24 BC; the temple was eventually dedicated in 2 BC, although not quite finished. Like the Forum

of Julius, this forum consisted of a rectangular space (measuring ca. 125m × 90m) lined by

two colonnaded porticoes. New, however, were the semicircular spaces (hemicycles) beyond the

colonnaded portico, possibly unroofed spaces that brought light through the colonnades. The

columns were made of different colored stone, with the fine Corinthian capitals of white marble.

Like the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum of Julius, the Temple of Mars Ultor, placed

against the rear wall of the forum, was the focus of the broad rectangular space (Figure 21.3). Its

Figure 21.3 Forum of Augustus with Temple of Mars Ultor (reconstruction), Rome