Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

322 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

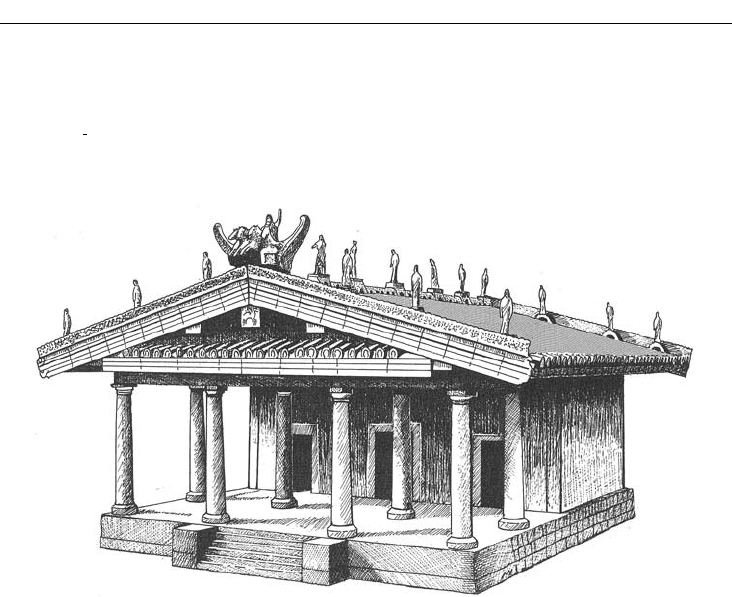

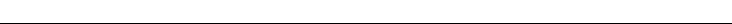

temple serves as a typical example of the Tuscan temple, an Etruscan form that would take its

place in the forefront of Roman religious architecture.

The Tuscan temple was discussed at length by the Roman architect Vitruvius in his treatise de

Architectura. The only book by an ancient artist or architect that has survived to modern times,

this work has had enormous influence on the understanding and appreciation of Greco-Roman

architecture. The Tuscan temple differs in key ways from the Greek temple (Figure 19.11). It sits

raised on a podium, and, as Vitruvius tells us (Book IV. 7, 1–5), it should be nearly square, six

parts in length, five parts in width, and further, it is divided into two equal parts, a deep porch in

the front, and a cella (or cellas) in the rear half. One enters from the front only, where a special

flight of steps leads up to the porch. The columns had smooth shafts, but rested on bases. The

capitals of this so-called “Tuscan order” are similar to the Greek Doric. Overall the Tuscan

temple offered an aesthetic impression quite different from the Greek: sitting high on a podium

and with emphasis on the front, in contrast with the visual unity of the Greek temple provided

by the surrounding steps and colonnade.

The temple at Veii consisted of a columned pronaos (porch) and a triple cella. The principal

divinity worshipped here was Menrva, the later Roman Minerva. The reconstruction shows the

wide eaves, designed to protect the mud-brick walls from the elements, which give the building

is distinctive top-heavy appearance.

The temple is dated to ca. 500 BC on the basis of its painted terracotta decorations. These terra-

cottas consist of plaques that covered the wooden structure of the roof; antefixes, the decorations

along the bottom of the roof tiles on the two long sides, some with spouts for the evacuation

of rainwater; and acroteria, here a group of statues that stood one after another in a line on the

ridgepole of the roof. Acroteria, both stone and terracotta, commonly decorated the roof lines

of Greek temples. The Etruscans, who absorbed this Greek habit, became particularly fond of

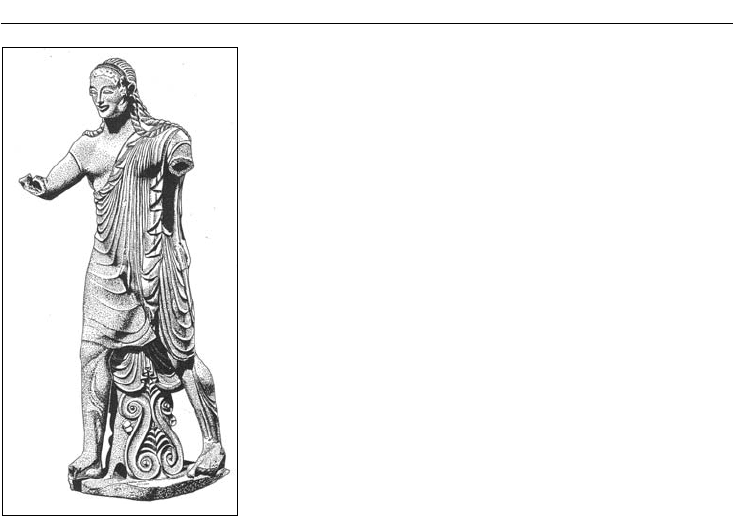

them. The best-known Etruscan acroterion comes from Veii, the life-sized “Apollo,” a terracotta

work whose style recalls that of Archaic Greek sculpture (Figure 19.12). This statue and its com-

panions from the Portonaccio temple were hollow, and fired in a kiln; their bases were specially

Figure 19.11 Reconstruction of an Etruscan temple, such as the Portonaccio Temple, Veii.

GREEK AND ETRUSCAN CITIES IN ITALY 323

shaped to fit the curved tiles that protected the ridge pole. The

examples from Veii were discovered broken, but carefully bur-

ied, a sign of the reverence in which they were held.

Tombs

The most striking monuments of the Etruscans are their

tombs. Constructed in permanent material (frequently carved

out of the bedrock, volcanic tufa), and often containing lively

wall paintings, sarcophagi with sculpted decoration, and abun-

dant grave goods, Etruscan tombs recall Egyptian burials and

indicate a similar devotion to preparations for the afterlife. Sur-

viving in vast numbers, these tombs and their contents are the

major source of information about Etruscan culture. In addi-

tion, the tombs have been important repositories for Greek

vases. The Etruscans appreciated Attic pottery, imported it,

and placed it in their graves. Like Egyptian graves, Etruscan

tombs have fascinated travelers, beginning in the Renaissance.

George Dennis, a British traveler, published in 1848 a famous

account of his explorations, widely consulted still today:

The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria. In addition to travelers, the

tombs have also attracted looters, from antiquity to the pres-

ent. With unscrupulous collectors ready to pay big money for

ancient objects, tomb robbers are in steady supply. Because of

these illegal excavations for which no records are kept, valuable information about the Etruscans

has been lost forever.

The Etruscans buried their dead in various ways. In the early centuries, cremation was the

norm. In northern Etruria, cremation remained popular until the end of Etruscan civilization.

By the fifth and fourth centuries, inhumation had become the prevailing rite in the south. In

inhumation, the body was wrapped in linen cloths, and set on a funeral couch or stone-carved

equivalent, or else placed inside a sarcophagus of wood or terracotta, or a stone imitation of a

wooden chest. After cremation, the ashes were placed in an urn, either metal or ceramic (such

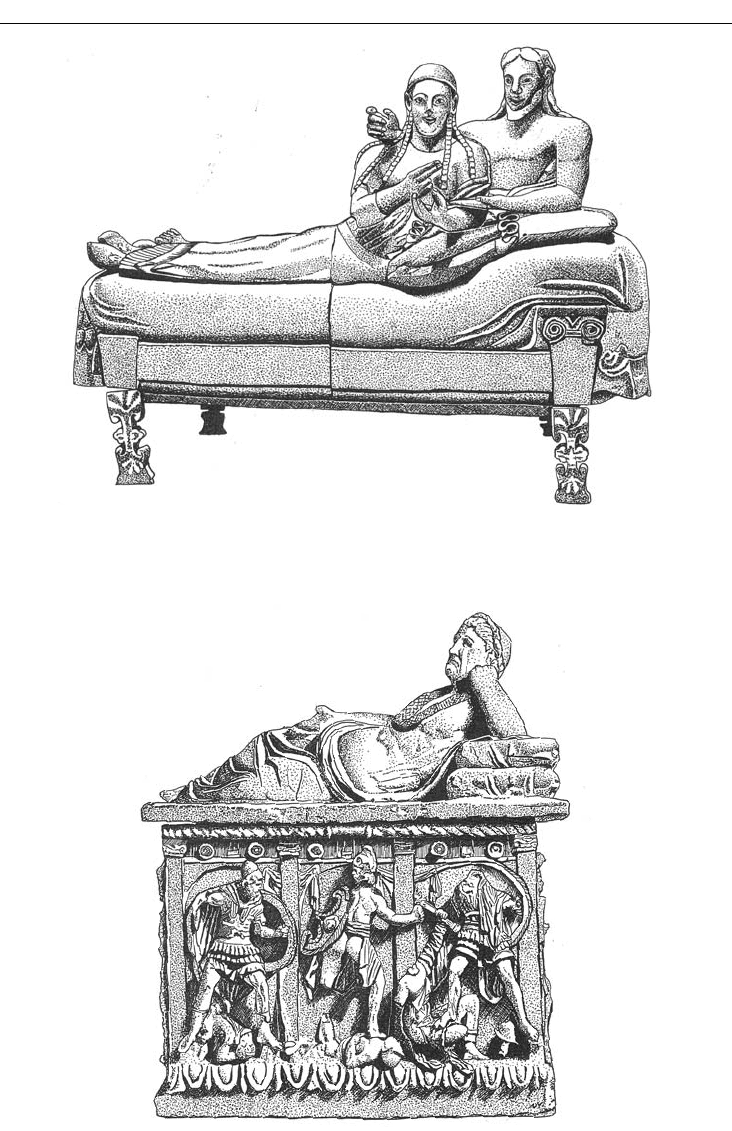

as Figure 19.8), itself placed in a tomb. A terracotta sarcophagus (probably a large ash urn) of ca.

525 BC from Caere (modern Cerveteri) shows a man and wife, life-size, reclining on a banquet

couch (Figure 19.13). Unlike the Greeks and early Romans, Etruscan women dined with their

husbands, one mark of the greater mixing of the sexes in private and public life. The couple

smiles in the Archaic manner borrowed from the Greeks, but within a few centuries Etruscan

urns and sarcophagi will show distinct portraits of individuals, not generic types (Figure 19.14). It

is possible that the Roman predilection for realistic portraiture derived from Etruscan practices.

The tombs themselves were either carved out of the tufa, or built underground with blocks

of tufa. Sometimes a cluster of tombs was covered with a tumulus. In other cases, the tombs

were not signaled above ground. The interior of the tombs resembled the inside of a house, with

rooms with pitched roofs, and as such, complement knowledge about houses gleaned from the

surviving foundations and debris discovered at habitation sites.

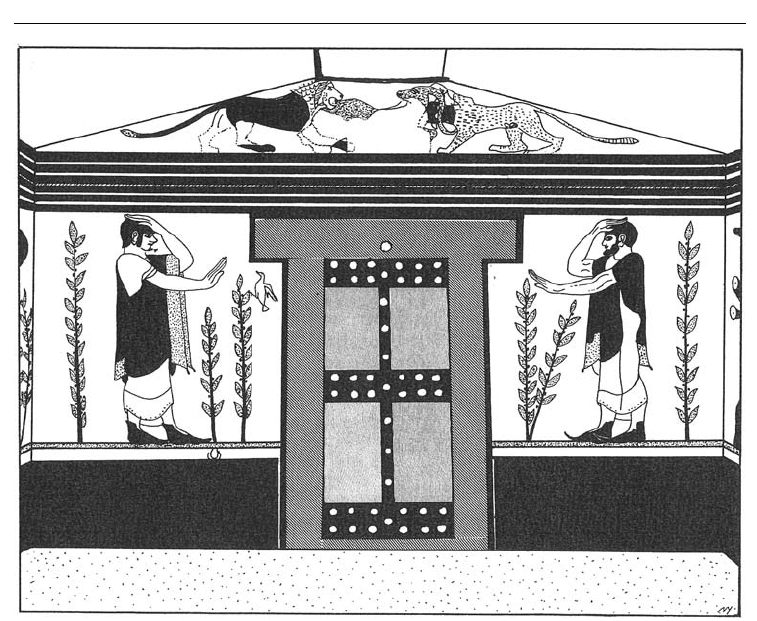

At Tarquinia, the vast cemeteries extend over the hills that ring the city. The Tomb of the

Augurs, ca. 530

BC, is a good example of an early chamber tomb with well-preserved wall paint-

ings (Figure 19.15). The tomb itself is small, a single chamber. The painted decorations display

Figure 19.12 Apollo, terracotta

statue from Veii. Museo

Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

324 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Figure 19.13 Terracotta sarcophagus of a married couple, from Caere (Cerveteri). Museo Nazionale

di Villa Giulia, Rome

Figure 19.14 Terracotta funerary urn, from Volterra. Deceased man (lid); battle with Gauls

GREEK AND ETRUSCAN CITIES IN ITALY 325

the arrangement popular from the sixth century onwards. In earlier tombs, painting was concen-

trated around a real or false doorway; depictions of animals or monsters, the guardians of the

gateway, were frequent. In the Middle Archaic Tomb of the Augurs, the entire wall space of the

chamber is covered. This decoration is divided into four horizontal zones: from bottom to top,

(1) a dado, or base, painted black; above this, (2) a tall zone with human figures walking on a red

base line; then (3) stripes, in place of the entablature; finally (4) a pedimental space. The rear wall

has a false door painted on it, a door with a solid lintel resting on posts that slope inward, the

door leaves strengthened with broad studs – the symbolic gateway to the world of the dead. Male

mourners stand on either side. Their costumes are forerunners of the Roman toga.

The rest of the room shows activities honoring the dead, funeral games and the attendant

festivities. The Romans relished the violent spectacle of gladiator combats; these too began as

funeral games, and it is tempting to search for their origin in Etruscan practice. On the long

side, two nude men whose names were painted above them wrestle over a stack of metal basins,

prizes for victory. Their contest recalls Greek practice. But other figures painted on the walls of

this tomb depart from the Greek world. To the left of the wrestlers, a robed man holds a curved

staff. This official has been interpreted as an Etruscan version of the Roman augur, or soothsayer;

hence the name of the tomb. To the right, a man wearing a demon mask holds by leash a dog

and a man, blindfolded by a sack over his head, whose thigh the dog is ferociously biting. Blood

is drawn; the shedding of blood, often depicted, was done for ritual or symbolic reasons. Blood

gave vitality to dead souls, for example. Elsewhere, a similarly masked man is taunting a runner.

Figure 19.15 Wall painting, Tomb of the Augurs, Tarquinia

326 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

These masked men are labeled phersu (= Latin persona), and seem to represent figures from the

underworld. In the pedimental spaces, lions attack a deer or gazelle.

Other scenes popular in tomb decoration include daily life, as in the scene of fishermen on

their boat, surrounded by birds, depicted on the rear wall of the interior chamber in the Tomb

of Hunting and Fishing, Tarquinia, ca. 510–500 BC. In the period just after 480 BC, paintings of

banqueters stretched out on couches and the dancers who entertained them became popular (see

Figure 19.13 for an earlier sculptural representation). It is not known whether the depictions of

banquets recalled the earthly life of the deceased, the funerary banquet held in his or her honor,

or the delights of life in the hereafter. The Tomb of the Leopards, ca. 480–470 BC, also from

Tarquinia, contains a good example of this subject.

Paintings in tombs of later centuries become gloomier, as if to reflect the pessimism of a soci-

ety aware of its irreversible decline. Quality of execution is no less good, however. The Tomb of

Orcus, at Tarquinia, shows new tendencies. The tomb consists of two chambers originally dug

separately, but later joined by a corridor for unknown reasons. The first chamber was decorated

ca. 350 BC, the second in the early third century BC. A banquet scene, damaged, decorated the

walls of the first chamber. A demon, Charun, now is present at this oft-shown meal, thereby

making clear that the event is taking place in the underworld. In Greek mythology, Charon was

the man who ferried the deceased across the River Styx, one element in the descent to the under-

world. The Etruscan Charun derives from the Greek Charon, but does not have a boat or the oar

that are the attributes of the Greek figure. Instead he wields a hammer and is depicted in far more

hideous form than Charon. He has companions such as the death angel Vanth and Tuchulcha,

a monster who hovers by Theseus in the underworld scene in the second chamber of the Tomb

of Orcus. In the painting from the first chamber of the Tomb of Orcus, Charun, himself painted

in a macabre greenish-blue, the coloring of a decomposing body, is magnified by the presence of

dark clouds that hover behind the banqueters.

A different type of Etruscan tomb was favored at Caere (Cerveteri). Here tumuli, sometimes

up to 33m in diameter, have been piled above clusters of underground rock-cut tombs. Between

tumuli ran streets, with ruts cut for ancient hearses still visible. Sometimes tombs follow the same

orientation, suggesting a family group; they would be reused for new burials. The tumulus, added

on top, gave a touch of monumentality to a family plot.

In early tombs, rooms were strung out in a line, on an axis. The interiors were modeled on

contemporary house types. We see a steep gabled roof line and a ridge pole in the Tomb of the

Thatched Roof, early seventh century BC. Later tomb types are more compact in the arrangement

of rooms. In the “Complex Etruscan Tomb Plan,” rooms were placed next to each other, with

their entrances off the main axis. Architectural features in this rock-cut construction included

corbeled vaulting in the entrance area, doorframes, windows cut through to rear chambers, ceil-

ing beams, columns with capitals, and an adaptation of a porch.

One of the largest tombs at Caere is the Tomb of the Painted Reliefs, early third century BC. In

a layout popular in the Etruscan Hellenistic period, the tomb no longer consists of small cham-

bers, but a single large space, its low ceiling held up by square pillars. The room is provided with

ledges and niches for up to approximately thirty burials. There are no wall paintings. Instead, the

walls and pillar faces display objects of daily life, such as cups, tools, kitchen tools, and armor, all

carved from the rock or formed in stucco; this relief sculpture was then painted. Cerberus, the

three-headed dog, guards the underworld, but humans are not shown. These relief sculptures

count as an unusual decoration for an Etruscan tomb, and among the most striking. A simpler,

earlier tomb with relief motifs is illustrated here, the Tomb of the Shields and Chairs, ca. 600–550

BC, also from Caere (Figure 19.16).

GREEK AND ETRUSCAN CITIES IN ITALY 327

Just as the Etruscans believed a person had a fixed number of years to live, so they believed

their cities and indeed their nation had a finite existence. Their nation was destined to last ten

saecula, a saeculum “corresponding to the longest lifetime of any person born at the moment

the saeculum commenced” (E. Richardson 1976: 249). And indeed, if we reckon 10 × 80 years

and begin at 800 BC, we reach the time of Augustus, by which time Etruscan culture had been

absorbed into the Roman. The Etruscans were astonishingly prescient about the duration of

their civilization.

Figure 19.16 Tomb of the Shields and Chairs, Caere (Cerveteri)

CHAPTER 20

Rome from its origins to the

end of the Republic

We now turn to the Romans, whose great civilization was the last to dominate the Mediterranean

region in ancient times. From modest beginnings at a fording point on the Tiber River in central

Italy, the city of Rome eventually controlled a huge territory stretching from Britain to North

Arabia, from the Danube River to Morocco. Admiring and assimilating Greek and Etruscan

culture in particular, the Romans created their own social and artistic synthesis, an outlook that

would profoundly influence the Mediterranean world and Europe well after the demise of pagan

antiquity, through the Middle Ages to the present day.

Roman history is divided into two main periods. After the initial settlement and a century of

rule by Etruscan kings, the Romans organized themselves as a republic. The Roman Republic,

the formative age of Roman civilization, lasted for nearly 500 years, from 509 to 27 BC. After

decades of disruptive civil war, Octavian, later called Augustus, brought peace to the waning

Republic, then transformed the state into a newly harmonious unity, the empire. Prosperous and

powerful for two centuries, the empire began to fracture in the third century AD. The Roman

Empire would nonetheless last into the Middle Ages, until AD 476 in its western half, accord-

ing to conventional periodizations, and until AD 1453 in its eastern, Byzantine half. This book

will trace the Romans to the fourth century AD only, to the end of pagan antiquity, when the

character of the empire was profoundly transformed by the change of the state religion to Chris-

tianity.

We begin with the origins of Rome and its subsequent development during the Republic.

Because evidence from the city is fragmentary, Republican Rome having been heavily remodeled

and rebuilt in imperial and medieval times, we shall complement our examination of Rome with

visits to other, better preserved towns for a fuller understanding of the period: in particular Cosa,

but also (in Chapter 22) two cities originating in the Republic that continued during the Empire

– Pompeii and Ostia.

Traditional foundation: 21 April, 753 BC

Etruscan rule: ca. 600–509 BC

The Roman Republic: 509–27 BC

Julius Caesar: prominent from 60 BC until his

assassination in 44

BC

His heir: Octavian

Battle of Actium: 31

BC

Octavian proclaimed Augustus in 27 BC

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 329

GEOGRAPHY

The city of Rome straddles the Tiber River at a point some 24km inland from the Mediterranean

Sea, at a ford (using the little island in the Tiber) on the north–south route leading northward to

Etruscan territory, and on the east–west route important in the transport of salt from the sea to

the Sabine herders and other peoples in the interior. This trade is reflected in an ancient street

name still used today, the “Via Salaria,” the “Salt Road.” The Tiber marks the boundary between

Etruria (the Etruscan heartland) to the north, and Latium, a region dominated by Rome. Latium

consists primarily of a plain, but also includes the Alban Hills and their lakes, created by volcanic

activity; these hills are a good source of tufa, the soft brown volcanic stone that Roman builders

favored. Rome itself encompasses seven main hills, projections of plateaus extending like fingers

westward toward the Tiber. Originally streams ran in the valleys in between the hills. Three of the

hills are close by the river – the Capitoline, the Palatine, and the Aventine – while the other four

lay behind – the Quirinal, the Viminal, the Esquiline (a cluster of smaller hills), and the Caelian

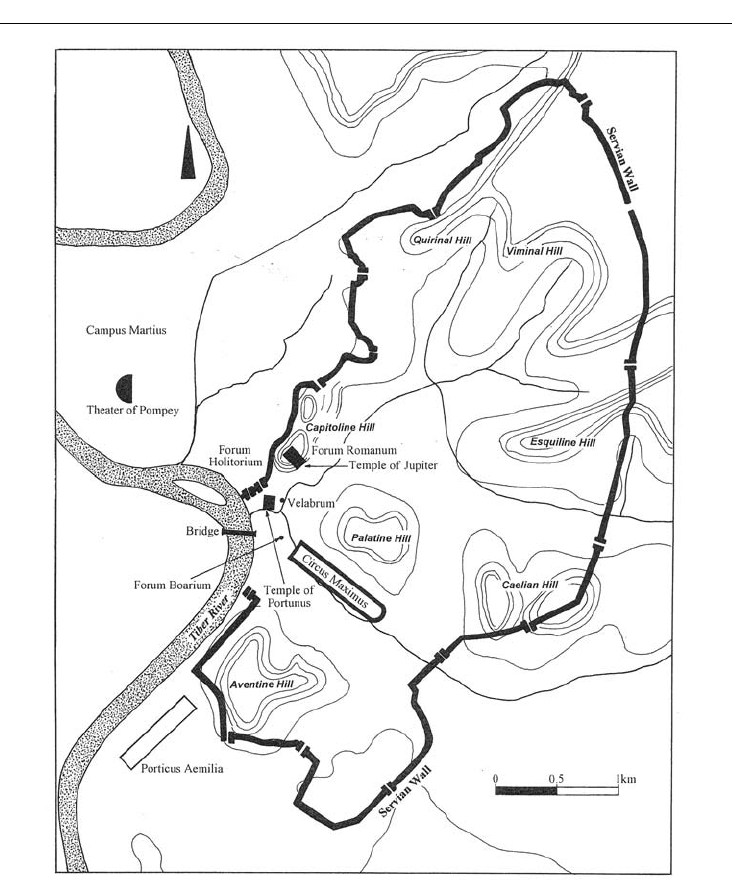

(Figure 20.1). As was true in Etruscan cities (and Veii is very close, only 20km to the north-east),

early occupation took places on the hills.

EARLY HISTORY AND SETTLEMENT, CA. 753–509 BC

The early history of Rome, such as it can be reconstructed from the legends recounted notably

by Livy, a historian of the Augustan period, divides into two periods, the first under the rule of

four Latin kings (ca. 753–600 BC), the second under the rule of three Etruscan kings (ca. 600–509

BC). According to legend, Rome was founded by Romulus and his twin brother Remus on April

21, 753 BC. As happened to such other leaders as Moses and Telephos (the mythical founder

of Pergamon), Romulus and Remus, grandsons of a deposed king of Alba Longa and poten-

tial threats to the usurper, were set adrift in a basket into the river. Instead of overturning and

drowning, the babies were rescued and reared to a glorious destiny. In this case, the rescuer was a

she-wolf, who nursed the boys at her own breasts until a herdsman and his wife took the children

under their care. From the early third century BC the Romans maintained a statue of a she-wolf

to commemorate the miraculous event, and indeed kept wolves in cages on the Capitoline hill.

In adulthood, Romulus and Remus restored their grandfather to his throne, then founded a new

city nearby: Rome (Roma, in Latin). Romulus killed his brother in an argument, but went on to

rule. In the fabrication of the legend, the names of the city and its founder have mingled; which

came first, Roma or Romulus, is not known.

Archaeology contributes an architectural and topographical reality to this mythological pic-

ture of early Rome. The earliest known settlement was on the Palatine hill. Foundations of huts

have been discovered, with holes to support the posts of the simple houses cut into the rock.

Houses were simple: one room, with walls of wattle-and-daub and vertical poles supporting a

thatched roof. They recall the houses of Iron Age Greece, and fit well with our picture of other

Iron Age villages in central Italy. Further evidence for the appearance of these houses comes

from hut urns, small pots in the shape of huts that held the ashes of a cremated body (such

as Figure 19.8). The steeply sloped roofs of these urns include a hole for the evacuation of

smoke, and suggest that the roofing material was straw or thatch. Such a hut stood on the slope

of the Palatine in later centuries. Carefully maintained until the fourth century

AD, often restored,

the Casa Romuli (House of Romulus) provided a conscious reminder of the humble origins

of the city.

330 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

The area at the foot of the north slope of the Palatine Hill was destined to be the site of

the Roman Forum. In earliest times, however, this low-lying, swampy terrain served as a burial

ground. In the eighth century BC, cremation was practiced. The ashes of the deceased were placed

inside hut urns or small pots; these were in turn put in a larger pot, itself set inside a circular pit

dug from the ground.

Changes in the town’s material culture occurred in the sixth century BC, the century of Etruscan

rule. The Etruscans, noted for their skills at regulating water, drained the swamps and channeled

the streams that fed them, especially in the area that would become the center of the town, the

Forum Romanum. Above, on the Capitoline hill that lies adjacent to the Palatine, they built their

Figure 20.1 City plan, Rome, Republican period

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 331

citadel and their principal temple, dedicated

to the god Jupiter. The possible remains of

this early Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, or

Jupiter Optimus Maximus, have been dis-

covered under the Renaissance Palazzo dei

Conservatori and the adjacent Palazzo Caf-

farelli on the south side of the Campido-

glio, the square designed by Michelangelo

for the twin summits of the Capitoline Hill.

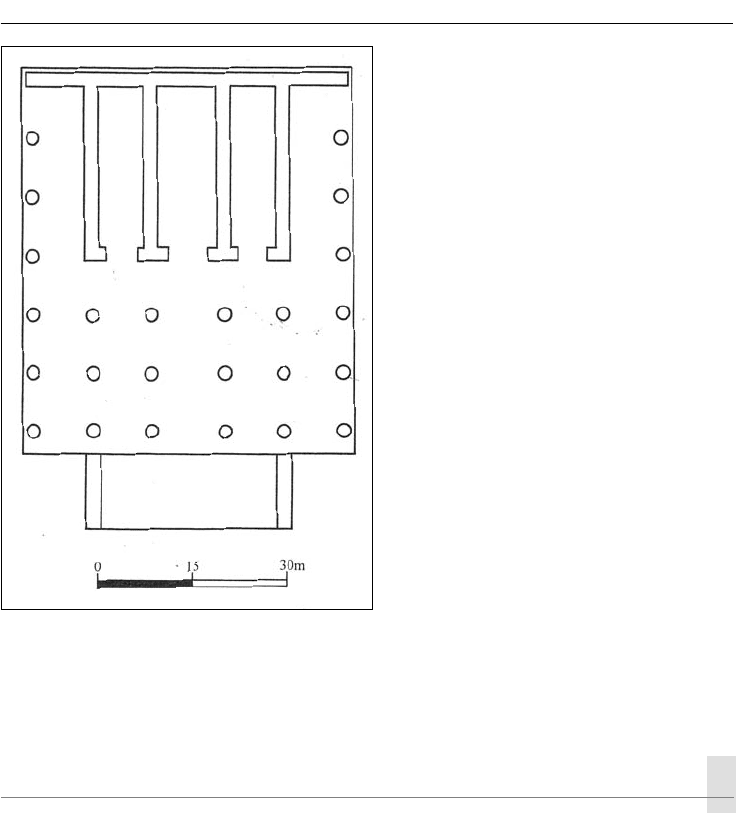

Because the ruins are scanty, the appear-

ance of the temple cannot be reconstructed

with certainty (Figure 20.2). We do know it

had three cellas in typical Etruscan fashion,

with Jupiter housed in the center, Juno and

Minerva on either side. These three became

the chief divinities of the Roman state. An

Etruscan artist, Vulca of Veii, was com-

missioned during the reign of Tarquin the

Proud (530–509 BC) to make a terracotta

cult statue of a standing Jupiter, painted red,

wielding a thunderbolt. This cult statue has

vanished, but the terracotta figures from the

Portonaccio Sanctuary at Veii (see Figures

19.11 and 19.12 ), roughly contemporane-

ous, give some idea of its appearance. The

temple would later burn twice, in 83 BC and

AD 80, to be rebuilt magnificently each time,

with the original layout piously preserved.

THE ROMAN REPUBLIC: CIVIC INSTITUTIONS

For nearly 500 years after securing independence from the Etruscan kings in the late sixth cen-

tury BC, Rome, the city itself and the territories it took over, was organized as a republic. The

word “republic” comes from the Latin res publica, “the public thing,” the Roman term for their

state – a loose, vague title for a strong, life-shaping notion of a social entity with clearly defined

obligations and rewards for its members. As in the Greek “democracy” (“power of the people”),

participation in running the Republic was restricted. Male citizens took charge, thereby exclud-

ing a large part of the population: women, slaves, and freedmen, and conquered peoples. Within

the male citizenry, power was weighted in favor of aristocratic families, especially if wealthy:

the patricians, as opposed to the common people, the plebeians. The central institution of this

oligarchy was the Senate, a council of, in the second century BC, 300 wealthy, influential citizens,

largely ex-magistrates, who were appointed for life. The Senate advised the magistrates, who in

turn brought their proposals to the citizenry at large for ratification (see below). Indeed, the Latin

formula Senatus populusque romanus (abbreviated SPQR), “the Senate and the Roman People,” by

whose authority laws were issued, indicates the prestige and power of the Senate. As the Repub-

lic grew, the increasingly powerful plebeians forced concessions from the patricians, thereby

Figure 20.2 Plan (reconstruction), Temple of Jupiter

Optimus Maximus, Rome