Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

102 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

them from the country. Thus began the Eighteenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom, the greatest

period in ancient Egyptian history.

THE NEW KINGDOM AND THEBES

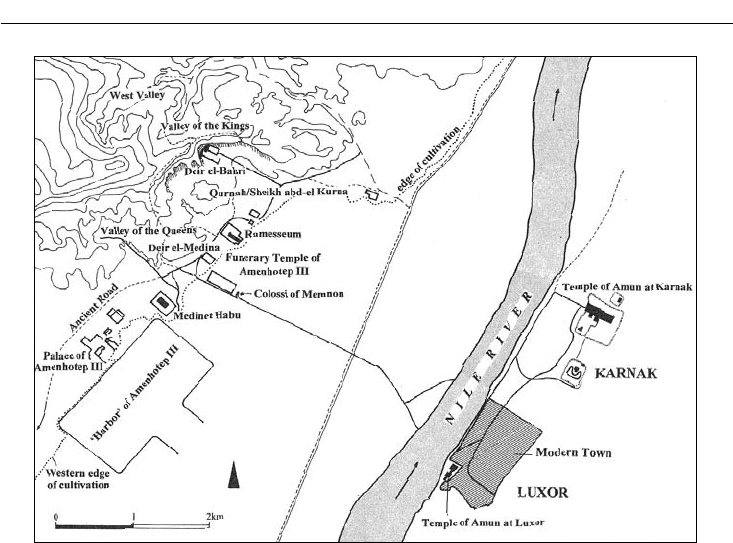

Three dynasties, Eighteenth to Twentieth, make up the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 BC). Most

major monuments preserved from this period lie in the region of ancient Thebes, modern Luxor,

the major city of Upper Egypt in ancient times. We shall also travel northwards from Thebes to

Tell el-Amarna for an instructive look at a New Kingdom city, and southwards to Abu Simbel,

to inspect the grandiose temple built by Ramses II (see map, Figure 5.1).

The Eighteenth Dynasty rulers established their capital in Upper Egypt at Thebes. Memphis

continued as a regional capital of Lower Egypt, but little survives. Thebes has a long history of habi-

tation, and indeed had been the royal center during the Eleventh Dynasty, but it gained particular

prominence at this time and served as a capital for most of the New Kingdom. The ancient Egyp-

tians called the city “Waset” or “No-Amun” (“City of Amun”). The name “Thebes” was given by

the ancient Greeks, for unknown reasons; there is no known connection with the famous Greek

city of Thebes. For the Egyptians, Thebes was “The City,” the prototype of all cities:

Waset is the pattern of every city,

Both the flood and the earth were in her from the beginning of time,

The sands came to delimit her soil,

To create her ground upon the mound when the earth came into being.

Then mankind came into being within her;

To found every city in her true name

Since all are called “city” after the example of Waset.

(Seton-Williams and Stocks 1993: 536)

The early rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty re-established control over Egypt’s frontiers and

trade routes. In the north, campaigns were led into west Asia against the Hyksos in Palestine and

the Mitanni in north-east Syria. More important was the south, where the Egyptians penetrated

Nubia beyond the Third Cataract, refurbishing the Middle Kingdom forts and establishing new

towns. An Egyptian trading mission to a more remote region, the land of Punt, usually identified

with the east horn of Africa, is recorded on the first of the great surviving buildings of Eigh-

teenth Dynasty Thebes, the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri.

Deir el-Bahri: the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut

The town of Thebes straddled both banks of the Nile. The habitation quarters, poorly known

today, must have been located on the east bank under the modern city of Luxor. Also on the east

bank are the two major temple complexes, the temples to Amun and other gods at Karnak and

at Luxor (see below). The west bank served different purposes. Some royal palaces were found

on this bank beyond the zone of cultivation, but today the region is better known for its cities

of the dead, the tombs and the temples devoted to funerary cults, and dwellings for those who

working making tombs (Figure 6.4).

Deir el-Bahri lies on the west bank, on the east side of massive limestone cliffs. To the west, on

the other side of the cliffs, is found the Valley of the Kings, the desolate burial ground of most

New Kingdom rulers. In this striking spot, adjacent to an important mortuary temple built by

the pharaoh Mentuhotep II of Dynasty XI, Hatshepsut (reigned ca. 1479–1457

BC) had a

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 103

magnificent temple erected for the perpetuation of her funerary cult. It marks a new trend, the

formal separation of the mortuary temple from the actual burial place, hidden far from the tem-

ple. The ruined temple at Deir el-Bahri was largely buried in sand and the debris of later Coptic

buildings when members of Napoleon’s expedition examined it in 1798. Serious excavation and

restoration work began in the 1890s under the direction of Swiss Egyptologist Edouard Naville

for the Egypt Exploration Fund, and continues today by a Polish/Egyptian team.

Rarely did women rule in their own right in ancient Egypt. Indeed, Hatshepsut began as co-

regent with her young nephew, Thutmose III, but quickly assuming full control and complete

royal regalia, she dominated the government for some twenty years. Although her texts fre-

quently used feminine grammatical gender, she had herself depicted as a man, the expected sex

of pharaohs, with the usual ceremonial beard. Her eventual fate is a mystery. Her mummified

body has not been conclusively identified, and no one knows whether she died a natural death or

was overthrown and killed. We do know that Thutmose III (reigned ca. 1479–1425 BC, including

the period of Hatshepsut’s co-regency) regained power, becoming one of the celebrated military

leaders of New Kingdom Egypt. But bad blood remained between them, it has been proposed,

for he did his best to eradicate all public mention of her by having her depictions and names

hacked away or replaced by his own.

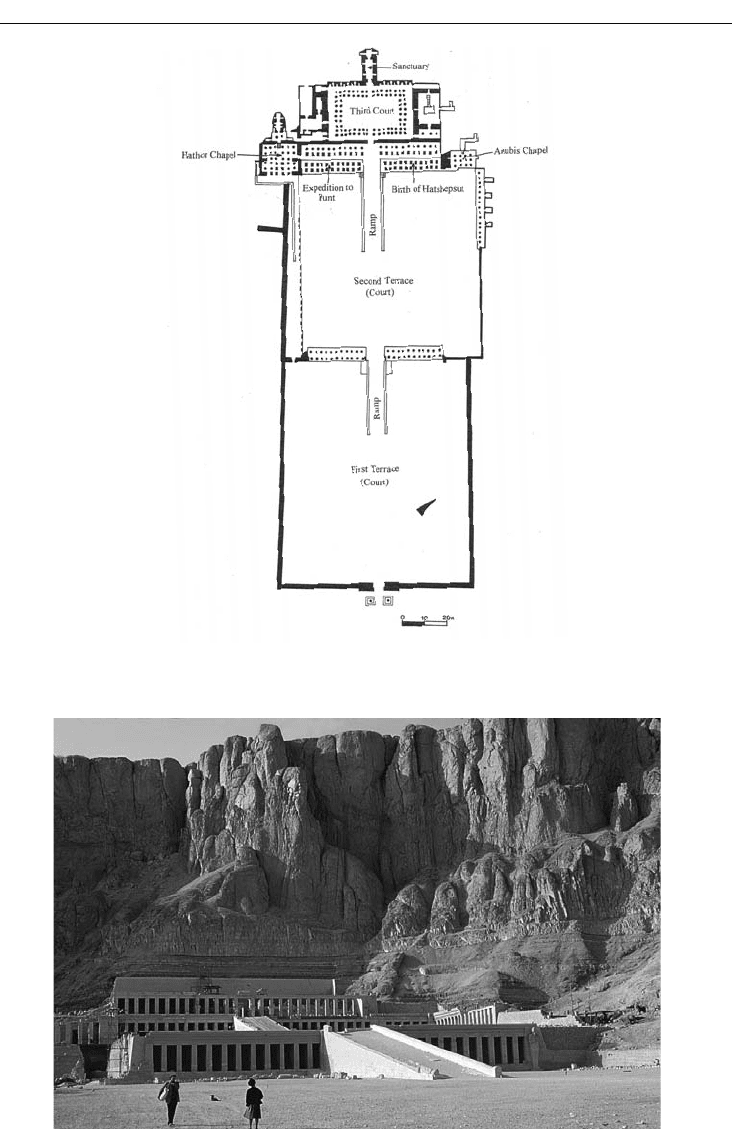

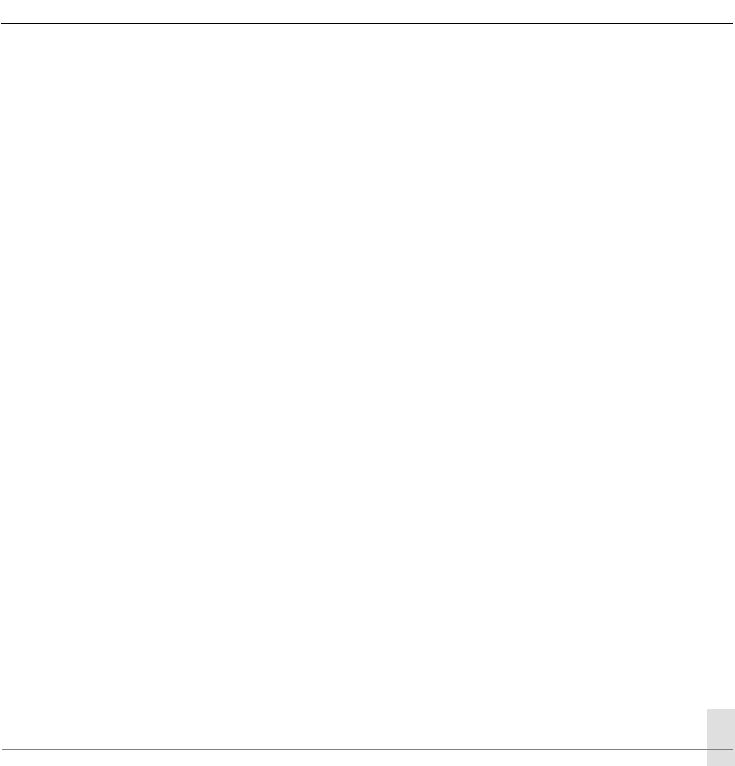

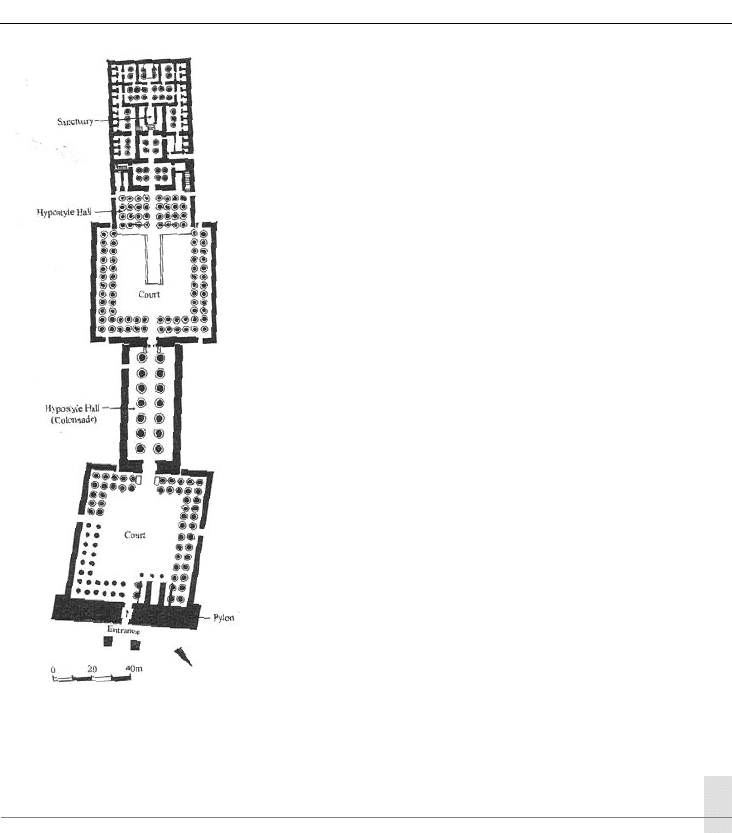

The temple is laid out on a series of three terraces (Figures 6.5 and 6.6). With its use of pillared

facades, the layout resembles models seen in the Middle Kingdom, both in the adjacent temple

of Mentuhotep II and in tombs or nobles elsewhere in Upper Egypt, and differs, as will be seen,

from the plan typical of later cult temples. The relief sculptures that decorate the walls sheltering

the colonnades promote the accomplishments of Hatshepsut, presenting a reign full of achieve-

ment despite the absence of the usual masculine exploits of war and hunting.

Figure 6.4 Regional plan, Thebes

104 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Figure 6.5 Plan, the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Deir el-Bahri

Figure 6.6 The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Deir el-Bahri

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 105

The lowest terrace consisted of a large walled area originally planted with trees. A double

colonnade, twenty-two columns arranged in two rows, lies at the rear of this terrace, divided into

two sections by the ramp that ascends to the second terrace. Painted reliefs on the rear wall of the

colonnade show the transport of the two obelisks Hatshepsut had made for the temple of Amun

in Karnak. The second terrace, smaller than the first, is itself bordered on the rear by a colonnade

(the Second Colonnade), again two sections of eleven columns arranged in two rows. The walls

of the south half display in painted reliefs scenes from the expedition to Punt, a distant land that

provided Egyptians with myrrh trees for the temple terraces, incense for religious ceremonies,

wild animals, electrum, hides, and timber. This delightful and unparalleled ethnographic record

illustrates scenes of the village of round huts on stilts where the Egyptians were received by the

chief, his obese wife, possibly a victim of elephantiasis, and their children. In the north section

of the Second Colonnade additional reliefs recount the divine birth of Hatshepsut. In order to

substantiate her right to rule, she asserted that her true father was not the pharaoh Thutmose I,

but the god Amun who entered the body of Thutmose I at the crucial moment of conception.

The full story was depicted here.

The Second Colonnade is flanked by two chapels, one on the south to the goddess Hathor,

and another, on the north, to the god Anubis. The portico of the Anubis Chapel and the colon-

nade that borders the north side of the second terrace just beyond the chapel are lined with a

series of columns that with their faceted sides and capitals, like columns from subsidiary build-

ings in the Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara, recall later Greek columns. Later Greeks were

indeed greatly influenced by Egyptian stone working traditions in architecture and sculpture, and

models such as these would have made a lasting impression.

A second ramp leads to the Third or Upper Terrace, an open-air court surrounded on four

sides by a portico. The sanctuary of the temple lies to the rear, cut into the limestone cliff, later

enlarged in Ptolemaic (Hellenistic) times, a small dark room typical of the Egyptian holy of

holies.

THE TEMPLE OF AMUN AT LUXOR

The main god of Thebes was Amun, worshipped as Amun-re, a fusion with the sun god, Re. He

formed a triad with his wife Mut and their son Khonsu. He is generally shown as a man wearing

a crown with two tall plumes and a disk, his characteristic headdress. The two major temples at

Thebes, one at Luxor, the other at Karnak, were dedicated to the cult of Amun, although both

complexes contained chapels to other deities. The Luxor Temple was also dedicated to the cult

of the royal ka, perhaps more so than to Amun. One might wonder what sort of relations these

large, neighboring temples enjoyed. One important link between the temples is illustrated on

the walls of the first hypostyle hall, or colonnade, in relief sculpture carved during the reign of

Tutankhamun (ca. 1336–1327 BC). Each year, at the height of the Nile flood, the Opet, or Great

New Year Festival, was celebrated. The statue of Amun was brought on his sacred barge from

Karnak to Luxor, highlighting the union of Amun with the king (the royal ka). This visit, lasting

some three weeks, was the occasion for sacrifices, pomp, and entertainment. This relationship

between the two temples, at least, was friendly.

In plan, both temples differ significantly from the funerary temples excavated at Giza and at

Deir el-Bahri. Little is known, however, of cult temples without funerary associations before

the New Kingdom. The Temple of Amun at Luxor is easier to comprehend than the temple

at Karnak, because it is the smaller of the two and because it was built in only two main stages

106 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

(Figure 6.7). The main part was constructed over an ear-

lier, smaller Middle Kingdom temple, by Amenhotep III

(ruled ca. 1391–1353 BC), a monarch who presided over

an exceptionally prosperous Egypt. In the following cen-

tury, the great Nineteenth Dynasty king Ramses II added

a court and the entrance pylon onto the north. (A pylon is

a gateway consisting of a wall, normally wedge-shaped in

cross-section – that is, with walls that slope slightly out-

wards from top to bottom – with a passageway through

the middle.)

The temple is oriented north–south, parallel to the

Nile, unusual for Egyptian temples which are normally

oriented east–west, attuned to the rising and setting of

the sun. Otherwise the temple follows tradition, contain-

ing the standard elements of a cult temple: an entrance

pylon; open-air courtyards; colonnaded (hypostyle) halls;

and a sanctuary surrounded by small cult rooms. These

elements had symbolic meaning. The sanctuary or small

holy of holies, the home of the god, where his or her statue

was kept, was built on the highest ground that symbolized

the original earth that emerged from the watery chaos at

the world’s creation. A hypostyle hall, with floor, columns,

and ceiling, represented the marshy ground of the earliest

world, the reeds that grew there, and the sky above. The

open-air court permitted worship of the sun; the pylon

represented the mountains of the distant horizon between

which the sun rises and sets.

THE TEMPLE OF AMUN AT KARNAK

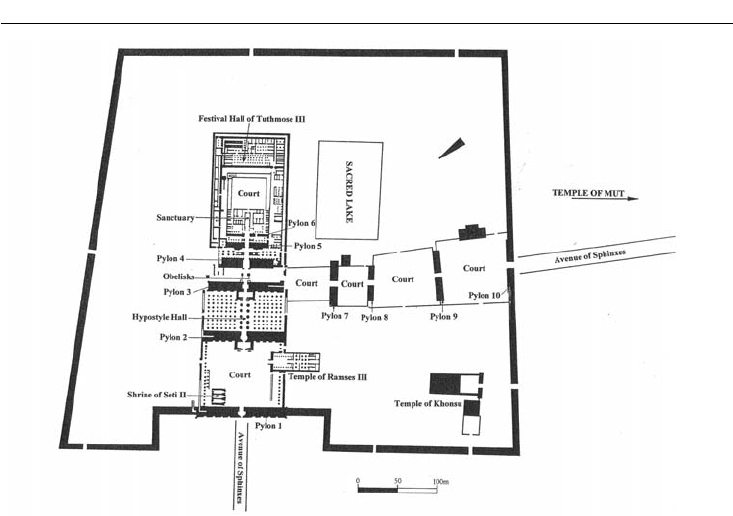

The Temple of Amun at Karnak follows the basic principles of temple layout seen at Luxor but

on a much grander scale (Figure 6.8). This temple had its origins in the Middle Kingdom. Indeed,

remains of the Middle Kingdom town of Thebes have been discovered in the precinct. But the

temple seen today is largely the work of the New Kingdom, with important additions of the Late

and Hellenistic Periods (first millennium BC). Its plan is agglutinative. The sanctuary, the residence

of the god’s statue, was the key room of a temple. Once this was built, an endless succession of the

other elements of a cult temple could be added: hypostyle hall, courts, and pylons. This is what hap-

pened at Karnak. It was not conceived as a unified plan; rather, a pharaoh would add a section to

the existing complex, thereby increasing the size of the building. Hatshepsut was a contributor, as

was Thutmose III; they were followed by many others. Some monarchs even disassembled existing

shrines, reusing the blocks in new constructions, or had their names inscribed in the place of the

original sponsors. The building history of the complex thus becomes difficult to unravel.

The ruins cover an area of 2ha, a large sacred precinct enclosed by a low wall that includes

the Temple to Amun with its southern projection, the Sacred Lake, and various small temples.

Figure 6.7 Plan, the Temple of

Amun, Luxor

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 107

Today’s visitor approaches the temple from the west along an avenue of sphinxes with ram’s

heads. The major section of the temple lies on this east–west axis. The avenue leads to the first

of the six pylons on this axis, the massive barriers or cross walls with doorways, sloping sides, and

niches for flagpoles that mark the transitions between inner and outer spaces. The so-called First

Pylon, the first entrance on the west, was the last to be built, begun perhaps during the Twenty-

fifth Dynasty; it was never completed.

The first court contains two temples of the later New Kingdom, a small tripartite shrine built

by Seti II to Amun, Mut, and Khonsu, and, on a north–south axis, a temple to the same triad

built by Ramses III. This last is more than a chapel; it is a complete temple in itself, with court,

hypostyle hall, and sanctuary.

The Second Pylon, contributed by Ramses II, included in its core a portion of the 60,000

small sandstone blocks that belonged originally to a Temple to the Aten, the sun god worshipped

as the sun disk, erected here at Karnak by the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten (other blocks were

found also inside the Ninth and Tenth Pylons and underneath the main Hypostyle Hall). In reac-

tion to Akhenaten’s religious policies, Horemheb, ruling soon after, had this temple dismantled,

but carefully, so the blocks could be reused. Beyond this pylon lies the great Hypostyle Hall,

completed by Seti I and Ramses II, and reconstructed in this century by French archaeologists

working for the Egyptian Department of Antiquities (Figure 6.9). This huge room, perhaps the

most famous in all Egyptian architecture, measures 102m × 53m, with the twelve columns along

the central passage rising 21m, the remaining 122 columns to the north and south rising 13m.

The higher columns in the center permitted a clerestory arrangement, that is, a line of windows,

which was the only source of illumination for this room. The resulting area is said to be large

enough to contain the entire cathedral of Notre Dame of Paris and the column capitals broad

enough that 100 people could stand on each. But the columns are thick and tightly spaced, and

it is difficult to sense the overall dimensions of the space.

Figure 6.8 Plan, the Temple of Amun, Karnak

108 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Such buildings devoted to the cult of the state god

served also as vehicles for the recording of royal achieve-

ments. This hypostyle hall is decorated on its columns

and side walls, both inside and out. The exterior walls,

for example, feature episodes from the military victo-

ries of Seti I and Ramses II. If the human audience for

these images was restricted, the gods were always pres-

ent. Royal successes accomplished with divine support

merited such commemoration on a grand scale.

The Third Pylon, built by Amenhotep III, the patron

of the Temple of Amun at Luxor, marks the beginning

of the earlier Eighteenth Dynasty section of the temple.

Modern exploration has revealed that this pylon, origi-

nally covered with gold and silver, contained in its fill

ten dismantled shrines and temples, notably the Jubilee

Pavilion for the Twelfth Dynasty pharaoh Senwosret I.

Re-erected just north of the main entrance, this pavil-

ion is the earliest building to be seen at Karnak today.

The Third Pylon is followed by the Central Court of

the temple. Two pairs of obelisks originally stood here,

gifts of Thutmose I, the mortal father of Hatshepsut,

but only one survives in situ. By the New Kingdom,

obelisks had become tall, slender poles, square in section with a pyramidal top, usually donated

in pairs perhaps for symmetry, perhaps to represent the sun and the moon. They were carved

from single blocks of granite, quarried near Aswan. The pink granite obelisk of Hatshepsut that

still stands between Pylons 4 and 5 measures 27.5m in height and weighs an estimated 320 tons;

its capstone was originally sheathed in electrum. Quarrying, transporting, and erecting such mas-

sive pieces of stone, which took seven months for these obelisks, would be an amazing triumph

of engineering even today.

A second set of courts and four pylons (pylons 7–10) extends southward from this court on

a north–south axis. These too date to the Eighteenth Dynasty. Pylons 7 and 8 are attributed to

Thutmose III and Hatshepsut, respectively, 9 and 10 to Horemheb. In the court just north of

Pylon 7, an enormous pit was discovered in 1902 which contained over 2,000 stone statues and

17,000 bronze figures, apparently a ritual clearing late in the temple’s history of the offerings left

in what must have been a very cluttered temple complex. From Pylon 10 one can leave the pre-

cinct sacred to Amun and follow a sphinx-lined route southward to the Temple of Mut.

Let us instead return to the main east–west axis and the early Eighteenth Dynasty core of

the temple. Pylons and courts become compressed here. Pylons 4 and 5, built by Thutmose I,

enclose a small colonnade, originally roofed. Some of the drama of Eighteenth Dynasty history

is attested in this small area. Hatshepsut had her pair of obelisks installed here, and removed part

of the roof to do so. Their transport is depicted on the rear walls of the First Colonnade at Deir

el-Bahri. Thutmose III not only replaced his aunt’s name with his own, but erected a wall around

the obelisks (as high as the ceiling of the hall) to hide them instead of tearing them down.

Beyond Pylon 5 lies a second small colonnaded hall, also erected under Thutmose I, and then

the last and smallest of the pylons, Pylon 6, an insertion of Thutmose III. Finally one reaches

the Sanctuary for the divine boat, a typically small room, long, narrow, and dark. The statue of

Amun lived here, and three times each day was washed by the high priest, dressed, perfumed, and

Figure 6.9 Central passageway, Hypo-

style Hall, Temple of Amun, Karnak

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 109

presented with food and drink. The original boat shrine was built by Hatshepsut; its dismantled

blocks have been recovered from inside Pylon 3. The present sanctuary, of pink granite, was a

late remodeling of ca. 330 BC, a contribution of Philip Arrhidaeus, the half-brother of Alexander

the Great. On the outside wall, south side, Philip is shown being crowned and taken in hand by

the gods. Despite Philip’s Greek origin, the style of these reliefs is purely Egyptian.

Behind the Sanctuary lie an open court and the Festival Hall of Thutmose III. Of the many

small rooms that lie beyond the hall, one is of particular interest, the so-called “Botanical Room,”

with reliefs of exotic plants, birds, and animals brought to Egypt by Thutmose III from his cam-

paigns in western Asia. To the south lies the Sacred Lake, 200m × 117m, fed by underground

channels from the Nile. Priests purified themselves in its waters. The visitor who finds himself

or herself here in the late afternoon is rewarded with a magnificent view of the ruined temple

illuminated in deep golden sunlight.

AKHENATEN AND TELL EL-AMARNA

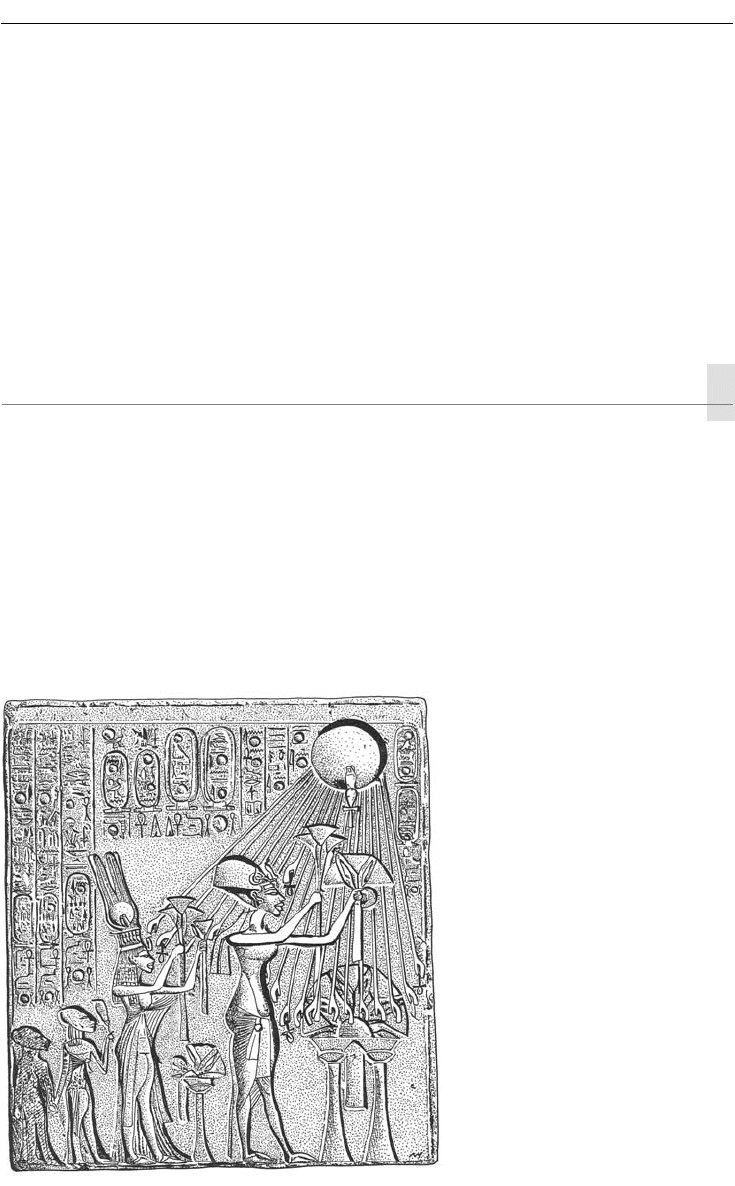

Amidst centuries of Theban preeminence, presided over by the supreme god Amun, one ruler of

startling originality briefly challenged this status quo: Amenhotep IV (ruled ca. 1353–1337 BC).

He became a passionate devotee of a single deity, the Aten, the life force depicted as a sun disc

with radiating rays (Figure 6.10). He changed his name to Akhenaten, meaning “He who is useful

to the Sun-disc” or “Glorified spirit of the Sun-disc,” and instituted a distinctive style for repre-

senting himself and his family in sculpture and painting, with exaggerated curves and elongations

of the head and body. And in the fifth year of his reign he moved his capital from Thebes to the

newly founded city of Akhetaten (“Horizon of the Sun-disc”), located halfway between Thebes

and Memphis. Akhetaten is commonly known as Tell el-Amarna, or simply Amarna, modern

names derived from two of the local villages, Et-Till and El-Amran.

Figure 6.10 Akhenaten and his family

worshipping the Aten, relief

sculpture, from the Royal Tomb,

Amarna. Egyptian Museum, Cairo

110 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

The ruins of Amarna give us our best and fullest look at an ancient Egyptian city. The reasons

are three. First, much of ancient Amarna lay just inland from the river’s flood zone; its remains

were thus accessible to archaeologists, not buried beneath meters and meters of Nile silt. Second,

the city had an extremely short life. Constructed on previously uninhabited land, the new capital

was occupied only during the final eleven years of Akhenaten’s reign and a few years after. The

site was then abandoned; apart from a small Roman fort, no building activity ever disrupted the

remains. And third, we know much about the city thanks to extensive excavations conducted

intermittently from the late nineteenth century until 1936, and again since 1977 by the Egypt

Exploration Society under the direction of British archaeologist Barry Kemp.

With such a short life, Amarna should not be considered typical. Established cities such as

Memphis must have been crowded, full of buildings arranged in haphazard city plans developed

over centuries. Nonetheless, the results from Amarna are valuable for their insights into four-

teenth-century BC Egyptian notions of what a planned city, and a royal capital, should look like.

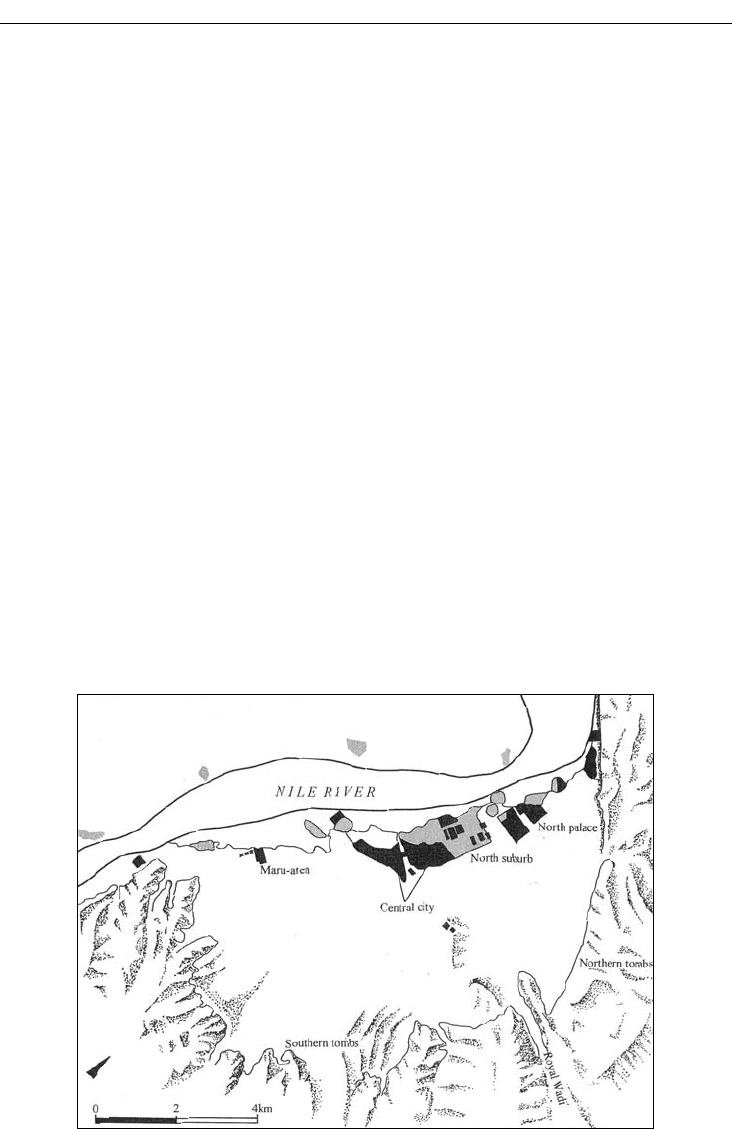

Although the city proper lies on the east bank of the Nile, a larger area totaling some 18 km

2

marked by fourteen boundary stelai extended across the river to the edge of the western desert.

The city was not walled. It was divided into various sectors, loosely linked by a north–south

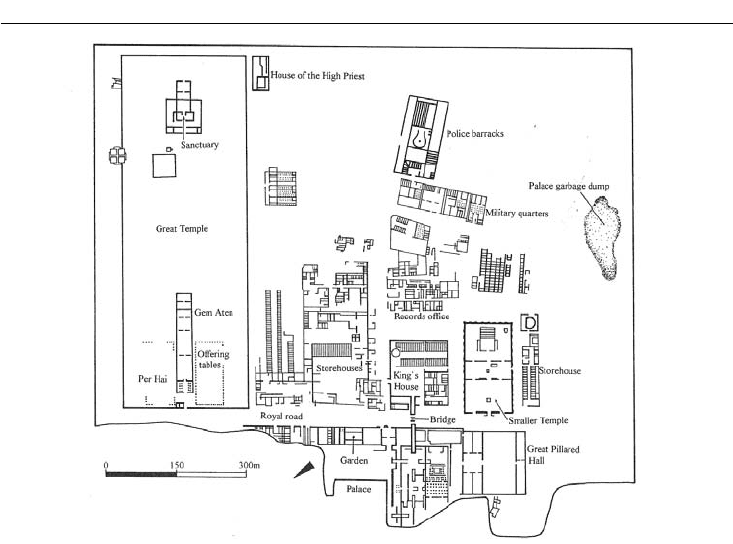

“Royal Road” that paralleled the river (Figure 6.11). Temples, storehouses, police barracks,

administrative buildings (including the “Records Office” that contained the invaluable “Ama-

rna Letters,” clay copies of correspondence with foreign states in west Asia), and a huge palace

occupied the central zone, laid out on a grid of streets in an orthogonal plan. Secondary residen-

tial and commercial areas were spread out to the north and south in a line that stretched over

8km parallel to the river. On the edge of the north suburb, an accretion of slum dwellings had

appeared by the end of the occupation of the town, crowding the more spacious housing. To the

east, an arc of desert cliffs provided the location for rock-cut tombs. Of these many informative

sectors we shall examine in more detail the palace and the Great Temple, both in the Central

Figure 6.11 Overall plan, Amarna

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 111

City (Figure 6.12), and the houses, which provide good evidence for the daily life of the ancient

Egyptians.

The Palace

The Palace straddles the Royal Road slightly to the south of the Great Temple. Much of the

complex lies beneath the zone of cultivation, and so has not been excavated and probably never

will be. Far larger than any private dwelling, the palace demonstrates the vast distance between

the pharaoh and the rest of society. Its plan consisted of a succession of flat-roofed buildings,

courts, and gardens, and larger pillared reception halls, some decorated with colossal statues of

Akhenaten. The king’s private quarters lay on the east side, the reception and administrative area

on the west. A covered bridge across the Royal Road linked the two sides. From a large window

in the bridge, the Window of Appearances, the pharaoh and his family could be greeted by their

subjects. The palace was built quickly, as were all buildings in this city, of mud brick, with wood

or stone for columns and such details as doorsills. Limestone revetments were used for wall

decoration. Some bore reliefs; some were plastered and then painted.

The Great Temple

The Great Temple occupied a large walled area, 760m × 290m. Our knowledge of the origi-

nal appearance of this temple and the rituals performed there depend on pictures of ceremo-

nies carved on the walls of tombs at Amarna. The main entrance lay on the west side, a small

brick pylon on the Royal Road. The sacred enclosure contained several shrines. A long narrow

building consisting of a hypostyle hall called the Per Hai, the “House of Rejoicing,” led to the

Figure 6.12 Plan, City center, Amarna