Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

72 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

the Great Bath served some ritual purpose involving water, not merely hygiene or sheer pleasure,

the main functions of later Roman bathing establishments.

Next to the Great Bath, on the west, was found the substructure of a building identified

as a granary by Sir Mortimer Wheeler, thanks to his explorations in 1950. This substructure,

whose original core measured 46m × 23m before an enlargement was made on the south side,

consisted of twenty-seven solid blocks of baked bricks divided by a grid of narrow passageways,

two east-west, eight (later nine) north-south. The building proper, set on these foundations,

was made of wood. Traces of the sockets for holding wooden beams were discovered embed-

ded into the brick podium. The passageways would have contributed to the aeration of the

building and its contents. Wheeler’s interpretation is controversial, however. The finds from the

building neither support nor disprove his theory, for they were not carefully recorded at the

time of the original excavations in the 1920s. All we can be certain of, then, is a large wooden

building. According to J. M. Kenoyer, this may well be a large hall. It does differ in design,

however, from another candidate for such a function, the “Assembly hall” located to the south

(see below).

A similar building at Kalibangan in the Indian Punjab may shed light on the function of this

building. Here, clear traces of ritual practice were found, evidence lacking in the “granary” of

Mohenjo-Daro. In the south part of the citadel mound at Kalibangan, brick platforms were sepa-

rated by narrow brick-paved passages. The surfaces of these platforms were damaged. On one

platform a row of seven fire altars was discovered, as well as a rock-lined pit containing animal

bones and antlers, a well head, and a drain. This area, entered by a broad flight of steps on the

south, must have been a ritual center for animal sacrifice, ritual bathing, and a cult of the sacred

fire. Similar fire pits have been found in a small brick-walled courtyard set apart in the lower town

of Kalibangan. Because fire worship was associated with the later Indo-Aryans, some scholars

have postulated their presence here, even at this early date.

Although it is tantalizing to imagine such functions for the “Granary,” excavations have not

yielded supporting evidence. The link between the two buildings may simply be in the common

approach to monumental architecture, with solid brick foundations separated by channels – a

structural basis that could be adapted for a variety of purposes.

Buildings to the north and east of the Great Bath at Mohenjo-Daro include one called the

“College.” Marshall attributed it to a high priest or group of priests, but there is no evidence to

support such an interpretation. Its function remains unclear.

The last of the major buildings on the citadel lies in the south-east, apart from the above-

mentioned three. The “Assembly hall,” as it is called, originally measured 28m

2

. Its interior was

divided into equal aisles by three rows of five brick plinths, bases for wooden columns. The floor

consisted of finely sawn brick work, recalling the typical flooring of bathrooms. Large square

rooms of this sort with columns or piers to hold up the roofing are found most notably in Egyp-

tian and Achaemenid Persian architecture, and served public gatherings on the grand scale, either

religious or secular. The name of the building, the Assembly hall, was suggested by this analogy.

The lower town

The town proper lies to the east of the citadel. Streets running approximately north-south and

east-west divided the large area into blocks of ca. 370m × 250m. Of perhaps twelve blocks, seven

have been investigated by archaeologists. The citadel may, in fact, occupy one of the central

blocks on the west side. Main streets could be as wide as 10m, while side streets were narrower,

CITIES OF THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION 73

1.5–3.0m in width. Although unpaved, the streets were provided with covered drains of baked

brick. Manholes, covered, located at periodic intervals provided access into the drains. Clay pipes

and chutes allowed waste material from private houses to reach the drains in the street. What

happened to the refuse when it reached the edge of the city is not known.

Private houses appear comfortable. They vary in size, from single-room houses to medium-

sized (court and one dozen rooms) to big (several courts, several dozen rooms). As in Mesopo-

tamia, the house focused on a central courtyard. Rooms surrounded it, usually arranged on two

stories. Baked brick was the standard building material for walls, an urban practice that contrasts

with the air-dried mud brick typically used in towns and villages. House floors consisted either of

beaten earth or brick, baked or air-dried. Roofing materials have not survived, but we may guess

they consisted of lighter timber, reeds, and clay, as elsewhere in the Near East. Cuttings, some-

times square, indicate the use of precisely cut wooden beams; such beams spanned distances as

great as 4m. Although mud plaster was occasionally used to coat internal wall surfaces, the walls

were never decorated with paintings.

Houses usually had their own well. Indeed, 600 wells have been found at Mohenjo-Daro.

Houses were furnished also with bathrooms, generally on the ground floor. The flooring of

bathrooms was lining with finely sawn bricks or, in some cases, a plaster of brick dust and lime.

Smaller rooms constructed in the same technique were identified as toilets.

Throughout the city, other buildings surely sheltered a variety of functions: residential, reli-

gious, or commercial. Of particular interest are the following. Some barrack-like groups of single-

roomed tenements were found, possibly housing for the poor, or even for slaves. House A1, a

building in the area labeled HR, may indeed be a prominent house, or it might be a temple. It

stands out, with its monumental entrance and double stairway leading to a raised platform on

which was discovered a rare stone sculpture of a seated figure. Other buildings with thick walls

or unusual plan have also been tentatively interpreted as temples, but the evidence is nowhere

compelling. Shops existed throughout the lower town; potters’ kilns, dyers’ vats, metal works,

shell-ornament makers, and a bead-maker’s shop have been identified.

The architectural features seen in this major city appear throughout the vast region

occupied by the Harappan civilization. The quality of the baked brick construction, the regu-

lar layout of city blocks in a rough grid plan, the extensive and well-built drainage system, and

the large buildings on the “citadel” indicate a complex society fully as sophisticated as any

seen in Mesopotamia and Egypt. In contrast, during the final stage of the Harappan period,

Mohenjo-Daro experienced a marked deterioration in town planning and in the quality of

construction.

LOTHAL

On the south-east edge of the Harappan world, in the Indian state of Gujarat, the ruins of

Lothal were explored in the 1950s by S. R. Rao of the Archaeological Survey of India. Although

much smaller than Mohenjo-Daro, this city displays many of the same key features of urban

design and architecture. Size differences thus did not affect the basic template of the Harappan

city.

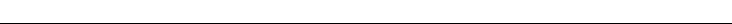

Laid out on a grid plan and provided with a good system of drainage, the city originally occu-

pied 12ha within a fortification wall (Figure 4.4). Later the town expanded beyond the wall, even-

tually doubling its area. Like other Harappan sites, Lothal too had its “citadel,” 48.5m × 42.5m,

built on an artificial platform of mud brick, ca. 4m high. But this citadel lay clearly within the

74 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

town and, unusually, in the south-east sector. The citadel would have served for defense against

floods, to secure storage for food, and as a showcase for the prestige of the rulers of the town.

The notable building on the citadel is a mud brick structure with ventilating channels, here, Rao

proposed, possibly the foundation for a warehouse.

In the town proper, the main street runs north–south. The principal streets are 4–6m wide,

the lesser streets only 2–3m. Houses were built of baked brick, and were routinely provided with

brick-lined drains. Workshops have been identified, among them a copper and goldsmith shop

and a bead factory.

On the east side of the city mound, at the edge of the citadel, lies Lothal’s most fascinating

monument, a massive brick platform alongside a large rectangular enclosure, ca. 225m × 37m

× 4.5m, lined with baked brick. The enclosure had a sluice gate at one of the short ends. Heavy

pierced stones, perhaps ancient anchors, were found on its edge. The excavator considered this

structure a dock for ships sailing up the river from the Indian Ocean. Lothal lies ca. 20km from

the sea, near a tributary of the Sabarmati River. Channels or estuaries would have provided a con-

nection with the river. If this interpretation is correct, Lothal has given us an unusually early and

sophisticated port installation from western Asia. A more recent analysis, however, has proposed

this to be a vast storage tank for fresh water in this low-lying region where the modern water

resources, at least, are saline. The issue is not yet settled.

Figure 4.4 City plan, Lothal

CITIES OF THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION 75

AGRICULTURE, TECHNOLOGY, CRAFTS, AND ARTS

The well-being of Harappan cities depended on successful agriculture. In addition, urban life was

enriched by a variety of crafts, no doubt the work of specialists. Agriculture prospered through

the natural flooding of the river. Evidence is lacking for irrigation, since alluvial deposits have

covered any traces of irrigation systems. Among the crops grown, wheat, barley, and millet were

staple cereals. Rice may have been grown in the south-east sector on the Indian coast. Mohenjo-

Daro and Lothal have yielded cotton cloth, rare evidence for early cultivation of this plant that

would continue to be so important for textiles of the subcontinent. Animals raised featured two

varieties of domesticated cattle, one humped (see Figure 4.5b), the other humpless. Other ani-

mals exploited included water buffalo, donkeys, and elephants.

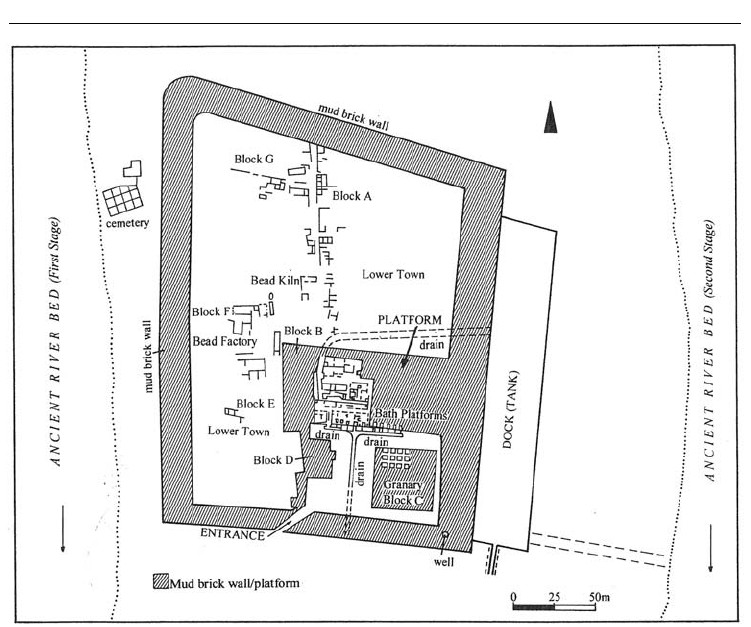

The best-known surviving craft is the stamp seal, usually made of steatite. About 2,000

examples have been discovered. Most are square with a perforated boss on the back for the

attachment of a cord. Round stamp seals and cylinder seals are rare. After the piece of stone

was cut with a saw, designs were carved with a small chisel and a drill. A coating of alkali was

applied to the entire surface, then heated to produce a luster. Animals were the favored subject.

The repertoire focused on animals of daily life, often shown posed in front of a standard, a

manger, or an incense burner, but imaginary composite creatures sometimes appeared

(Figure 4.5). Most seals were inscribed. At Lothal, several clay sealings with impressions of cord

or matting on the rear were found among the ashes in the ventilation shafts of the brick plat-

forms of the “granary” or “warehouse.” This find spot suggests that these seals had a commercial

function.

Such stamp seals as well as etched carnelian beads, bone inlays, and other small objects have

been found at Mesopotamian towns dating from ED III through the Larsa period (2600–1750

BC). Indeed, Harappan traders set up a small colony at Tell Asmar, where their houses stand

out because of the fine bathrooms, toilets, and drains. In contrast, Mesopotamian objects are

exceedingly rare at Harappan sites. Imports from Mesopotamia and south-west Iran (Susa)

must have consisted of raw materials or perishable products, foodstuffs and textiles, transported

Figure 4.5 Stamp seals, with (a) unicorn, and (b) humped bull, both from Mohenjo-Daro. National

Museum, Karachi (a); and Islamabad Museum (b)

76 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

principally by middlemen by boat through the Persian

Gulf. Evidence for an overland route is meager.

Metallurgy was practiced, copper and bronze for

tools, with gold used for jewelry. Pottery, a develop-

ment of the Neolithic period, continued to be produced,

now including examples painted with motifs both deco-

rative and, it seems, religious. Textiles may have been

a focus for Harappan creativity, although evidence for

textile production is scanty. A well-documented craft

of Harappan cities is bead making, thanks to finds of

workshops with materials, tools, and beads in differ-

ent stages of completion. In addition to the above-

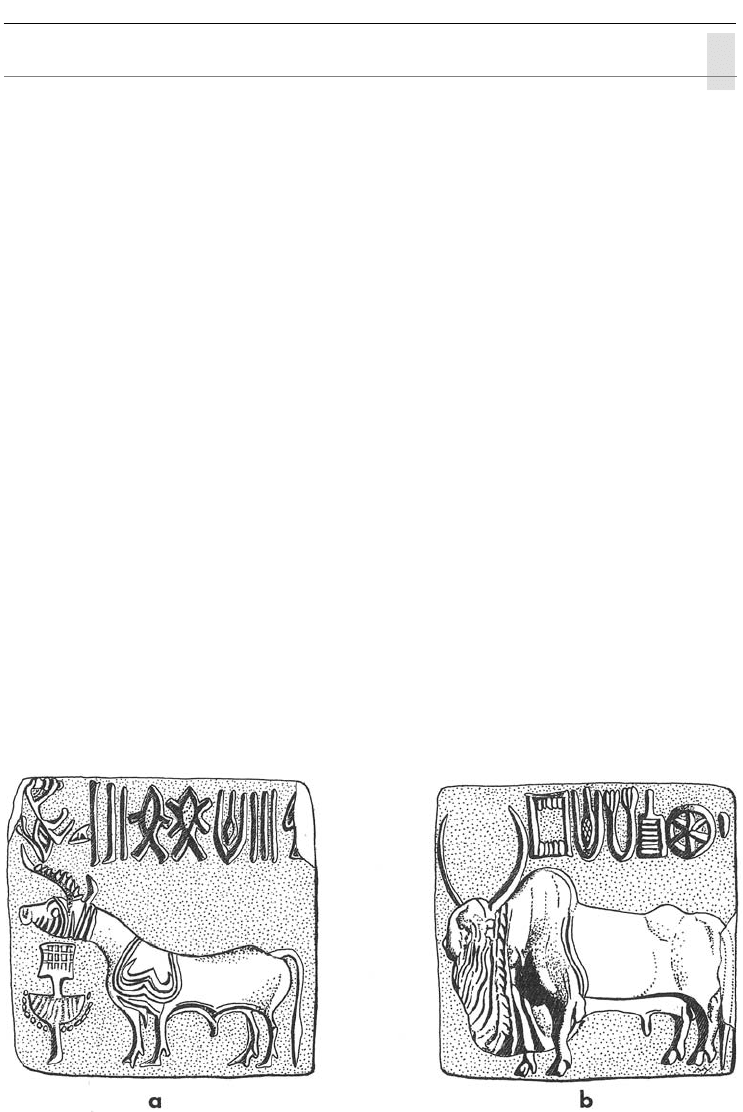

mentioned products, terracotta figurines of birds, ani-

mals, and humans are frequent. An elaborately dressed

and adorned female, well represented among these

figurines, might be a goddess. Sculpture in stone and

metal was rare and tended to be small in scale. Most

examples of stone sculpture were cult images des-

tined for temples, it is thought. A bronze statuette of

a dancing girl from Mohenjo-Daro must have filled

some quite different purpose (Figure 4.6). Approxi-

mately 11.5cm high and cast in the lost wax method,

she came not from a temple, but from a private

house. Clad only in a necklace, an elegant hairdo,

and a mass of bracelets, this woman delights us with

her jaunty pose and cool, confident expression.

This kind of vignette is unusual in the art of south-west Asia, in which stiff formality is much

preferred.

Lacking in Harappan representational art are clearly identifiable images of rulers. Also absent

are depictions of warfare. Both subjects are staples of Mesopotamian art, as we have seen. Among

the many Bronze Age civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, and the Near East, only

Minoan Crete (see Chapter 7) similarly excludes both rulers and warfare from its arts. One must

wonder what elements of government and society these two otherwise very different cultures

might have had in common that would result in such a distinctive approach to the subjects

deemed appropriate for pictorial art.

THE END OF THE HARAPPAN CITIES

The Harappan phase of the Indus Valley Civilization came to an end some time at the beginning

of the second millennium BC. The unified urban civilization dissolved into local village-based

cultures lacking the technological and architectural competence of their predecessors. The break-

down was gradual, the result of many factors. Some elements can be spotted. Environmental

changes weakened the economy, such as flooding, deforestation, and overgrazing, and the drying

up of the Saraswati River. Other factors elude us, such as possible political and religious changes.

Early in the modern study of Harappan civilization, invasions had been proposed as an agent of

change. Speakers of Indo-European languages, the writers of the Rig-Veda and the ancestors

Figure 4.6 Dancing girl, bronze figurine,

from Mohenjo-Daro. National Museum,

New Delhi

CITIES OF THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION 77

of most of the inhabitants of the northern half of India today were thought to have entered the

sub-continent at this time. But traces of invasion are few on Harappan sites. A suitable group of

skeletons scattered in the latest habitation of Mohenjo-Daro may show the eruption of violence,

but this has yet to be matched at other sites. Outright invasion is thus rejected now as an expla-

nation of the dissolution of the urban culture of the Harappans. Future excavations will surely

continue to shed light on what must have been a complex series of events.

CHAPTER 5

Egypt of the pyramids

INTRODUCTION

The civilization of ancient Egypt, the third of the three great river-based cultures of West Asia

and the East Mediterranean basin, stands in brilliant contrast to both Mesopotamia and the

Indus Valley. The Egyptian remains seem so abundant, so well preserved, so awesome: pyramids,

gold coffins, inscriptions meticulously chiselled in stone. In contrast, Mesopotamian remains

can seem drab and fragmentary, the Harappan curiously limited. This state of affairs represents

an accident of survival. The Egyptians lavished attention and material resources on religion

and death. Temples and tombs were either built or carved from stone and, thanks to remote

locations or the protective covering of sand, these stone structures have survived remarkably

well.

The impression such monuments give is that ancient Egypt was a civilization without cities.

The reality was different. The Egyptians had cities, but archaeologists have generally ignored

them because their remains are difficult to trace. For civic buildings, houses, and even palaces,

sun-dried mud bricks were the preferred building material – much less resistant than the stone of

the temples and tombs. Compounding the archaeological problem, towns were situated along-

side the Nile and so have been buried deep under the mud left by the annual flooding of the

river, and in some cases covered by habitation continuing to the present day. When excavators

have not shied from the practical difficulties, their results not only confirm that the Egyptians

had cities, towns, and villages but also make clear that these settlements played a key role in the

perpetuation of Egyptian culture.

Because of this distinctive case of material survival, this chapter and the next will concen-

trate less on the remains of cities than on other sorts of experiences an Egyptian city or town

dweller would have encountered during his or her lifetime. Aspects of Egyptian life that we

shall explore include the power of the ruler as conveyed through art and architecture; rituals and

Predynastic: ca. 5000–3050 BC

Early Dynastic (Archaic): ca. 3050–2675 BC

First and Second Dynasties

Old Kingdom: ca. 2675–2190

BC

Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Dynasties

First Intermediate period: ca. 2190–2060

BC

Seventh to Tenth Dynasties and earlier Eleventh Dynasty

EGYPT OF THE PYRAMIDS 79

religious architecture; burial practices, tombs, and funerary monuments; warfare, weaponry, and

fortresses; and geography, economy, and trade. But towns and cities will not be ignored, with

Kahun, Amarna, and greater Thebes examined in Chapter 6.

GEOGRAPHY

The borders of modern Egypt trace a large area, but most of it consists of desert. Only a small

portion can sustain human life, the fertile strips alongside the Nile and a handful of oases in the

western desert.

The Nile runs northward from two main sources: Lake Victoria in central Africa and Lake

Tana in Ethiopia. The White Nile and the Blue Nile, as these two branches are called, join at

Khartoum, the capital of the Sudan, and continue another ca. 3,000km until emptying into the

Mediterranean Sea. At six places between Khartoum and Aswan the smooth course of the water

is obstructed by granite rock formations known as “cataracts” that render navigation difficult.

These cataracts are numbered from north to south, in reverse order to the direction of the river’s

flow. The First Cataract, located at Aswan some 950km south of the Mediterranean, marked the

southern boundary of ancient Egypt.

For much of its course northward from Aswan, the Nile flows through a narrow channel

formed first in granite (at Aswan), then sandstone (from Aswan to Edfu), and finally limestone

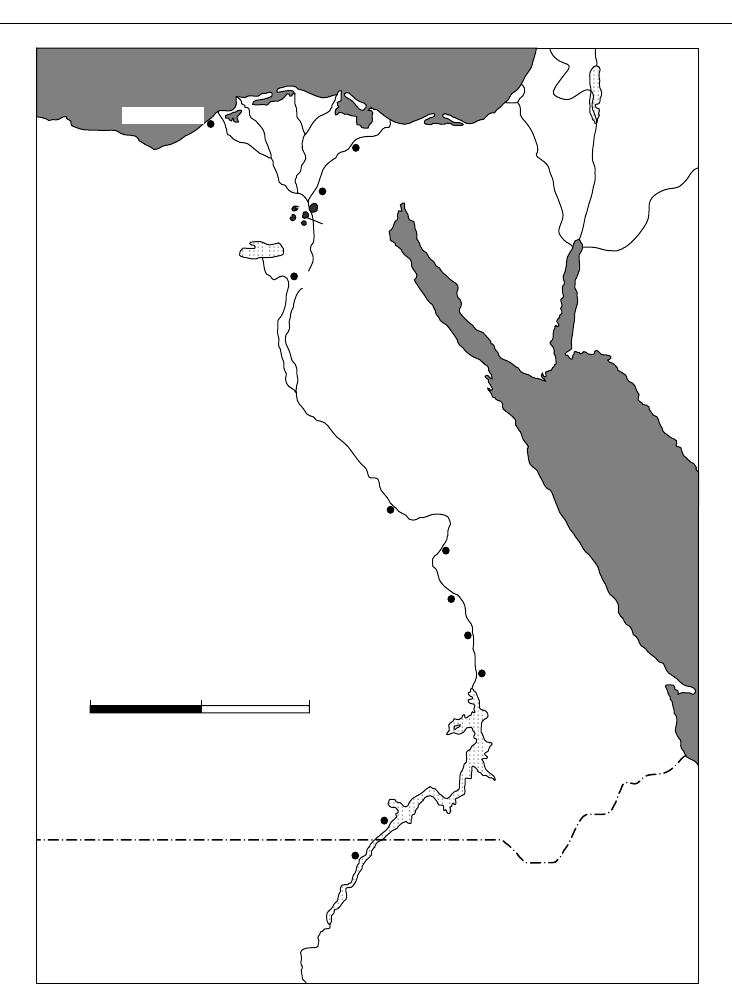

(from Edfu to Cairo) (see Figure 5.1). Just north of Cairo, the Nile enters a flat coastal plain and,

as it makes its way to the Mediterranean, fans out over an area shaped like an inverted triangle

– the inverted form of the Greek letter “delta,” as the ancient Greeks observed. The long, narrow

stretch from Aswan to Cairo and the short, broad delta marked two distinct regions in ancient

Egypt: Upper Egypt, the former (called “upper” because it lies upstream), and Lower Egypt, the

delta. Unification of the two regions (in ca. 3050 BC) marked the beginning of Egyptian history,

but during times of governmental crisis the two areas would typically split apart.

Because Egypt has little rainfall, the fertility of the land has depended on the Nile and espe-

cially, until the construction of the Aswan High Dam (built in 1960–71) blocked the natural flow

of the river, on its annual flood. Swelling from spring rains in central Africa and the Ethiopian

highlands, the river becomes rich with silt washed from the hills. Gradually this surfeit of water

and silt travels northward, reaching Egypt a few months later. Egypt saw the Nile at its lowest

in May, but then the river would rise until mid-August when it spilled over its banks into the

adjacent fields. For two months the land lay buried beneath the floodwaters. Then in October

the river receded, flushing away noxious salts and leaving behind a new layer of rich, fertile soil.

Farmers repaired their system of dikes and began the chores of planting. A 6m–9m rising of the

river was reckoned beneficial. A higher or lower rising could seriously disrupt the agricultural

system, causing famine in the worst instances. Small wonder that the Egyptians worshipped the

flood as a god, Hapy – a man, but supplied with pendant breasts and belly, attributes of fertility.

The Aswan Dam now keeps the waters at predictable levels, but the nourishing silt no longer

comes. Artificial fertilizers must be used, and damaging salts have built up in the soil.

EARLY HISTORY

Egyptian history proper, dynastic Egypt, begins with the unification of the country ca. 3050 BC.

In chronological terms, this corresponds to the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.

80 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Following this event, Egypt was ruled for nearly 3,000 years by a sequence of thirty dynasties,

or ruling families (see the Introduction). These dynasties have been grouped by historians into

periods of strength and weakness. The three great periods of cultural achievement, marked by

a strong central government, are known as the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the

Giza

Abu Gurab

Saqqara

Memphis

Cairo

Heliopolis

Avaris

Faiyum

Kahun

Abydos

Thebes

Aswan

Hierakonpolis

Edfu

Abu Simbel

Buhen

SUDAN

NUBIA

Nile River

Israel

PALES

JORDAN

SINAI

SAUDI ARABIA

EGYPT

0 100 200km

Alexandria

Alexandria

R E D S E A

RED SEA

Figure 5.1 Egypt

EGYPT OF THE PYRAMIDS 81

New Kingdom. Each was followed by a period of weakness in which the central government

disintegrated, with regional rulers wielding power: the First, Second, and Third Intermediate

Periods. The Late Period, which followed the Third Intermediate Period, comprises the final

centuries of independent Egypt before the conquests of the Persians, Greeks, and Romans.

According to Manetho, the important ancient chronicler of Egyptian history, the unification

of Upper and Lower Egypt ca. 3050 BC was accomplished by Menes. The name “Menes” is not

attested on remains or documents of the period, however. Instead, those objects indicate a king

Narmer as the great conqueror, but it may be that Menes and Narmer are in fact the same person.

In any case, Manetho may have simplified events. Mounting evidence suggests that political and

cultural unification did not occur suddenly, but developed over 100–200 years, with the south

gradually imposing its control over the north. The term “Dynasty 0” is used by some to denote

this period of transition.

The Narmer Palette

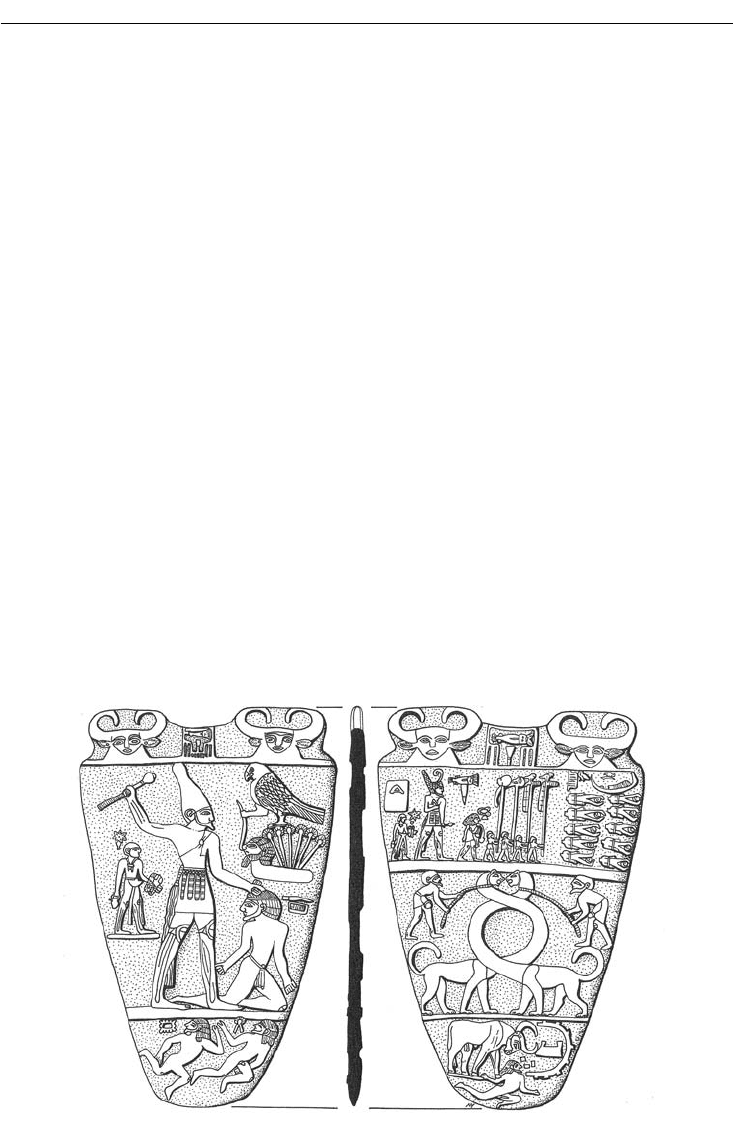

Striking evidence for Narmer and the unifi cation of Egypt comes from the Narmer Palette

(Figure 5.2). Slate palettes were fl at slabs much used in Predynastic Egypt for the grinding of

minerals for cosmetics. Although most were small, some, like the Narmer Palette (63cm high),

were large ritual objects, elaborately decorated with relief carving. Found in 1898 during the

excavations of J. E. Quibell in the Temple of Horus at Hierakonpolis, the Predynastic capital of

Upper Egypt, the Narmer Palette was evidently a votive gift to the temple.

The scenes carved in relief on both sides of this palette represent a remarkable pictorial expres-

sion of contemporary events that is rare for its time. They illustrate the victory of Narmer: the

conquest of northern Lower Egypt by southern Upper Egypt. Narmer is named in a glyph denot-

ing the king on both sides of the palette, on the top between images of Bat, a sky goddess, shown

with cow ears and horns and a human face. On one side, the king dominates the scene. Wearing

Figure 5.2 Narmer Palette: obverse, cross section, and reverse. Slate palette, from Hierakonpolis.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo