Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

42 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

The ED period and the first era of Sumerian supremacy came to an end with the victory of

Sargon the Great, the Semitic ruler of Akkad, over Lugalzagesi, the powerful ensi of Uruk, and

Sargon’s subsequent conquest of the entire region (see Chapter 3).

To illustrate selected aspects of ED city life, we shall examine the Temple Oval at Khafajeh

and evidence for temple decoration and religious practice from Ubaid and Tell Asmar, and an

important cemetery at Ur, the so-called “Royal Tombs.”

EARLY DYNASTIC RELIGIOUS LIFE: THE TEMPLE OVAL

AT KHAFAJEH

Sumerian cities of the ED period were located on a watercourse and protected by fortification

walls. As before, temples to the patron deity, his or her spouse, and their children occupied

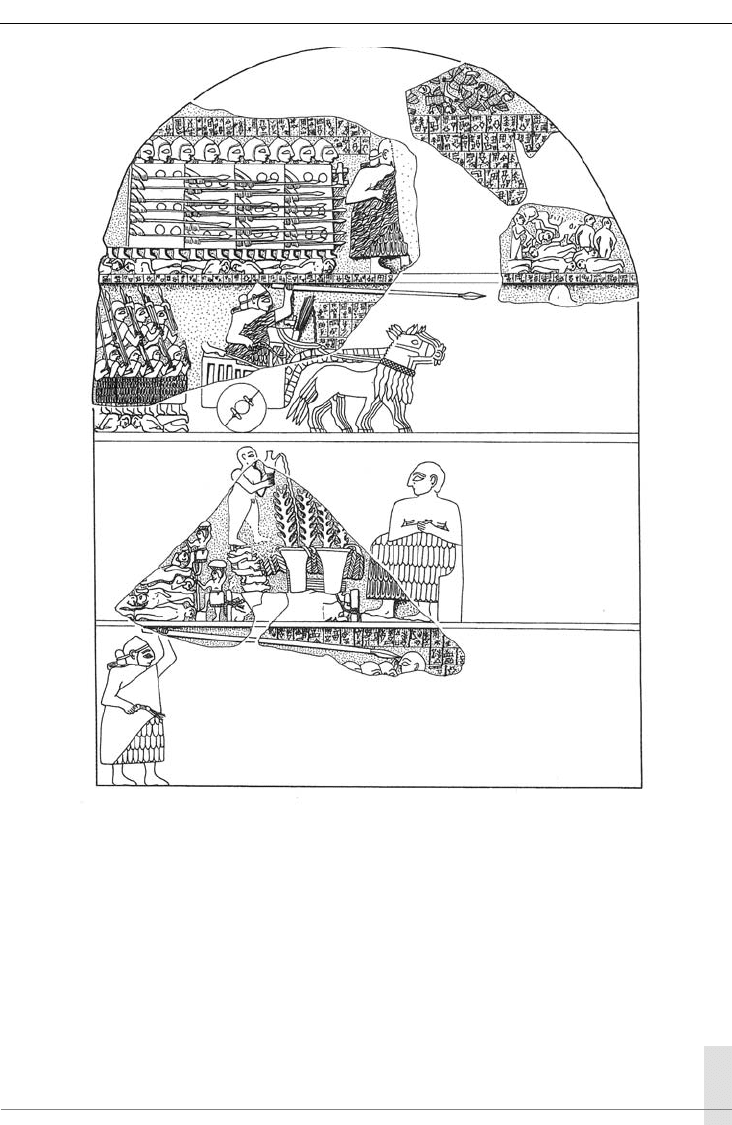

Figure 2.11a Obverse, Stele of the Vultures, ED III, from Telloh (Girsu). Louvre Museum, Paris.

EARLY SUMERIAN CITIES 43

a prominent position in the town. Smaller shrines, popular as well as official, were scattered

throughout the city, in residential quarters marked by cramped and winding streets. Construc-

tion of huge palaces began in the ED III period, reflecting the increasing power and wealth of

the ruler. These palaces, of which good examples can be seen at Eridu, Ubaid, Kish, and, to the

north-west, Mari, served both as residence of the king and as the administrative and bureaucratic

headquarters. But it is the religious buildings that continue to be so distinctive of Sumerian

cities.

The coexistence of a “high temple” with “ground-level temples,” which we have seen at Pro-

toliterate Uruk, is a pattern that is maintained in the layout of a Sumerian city’s religious build-

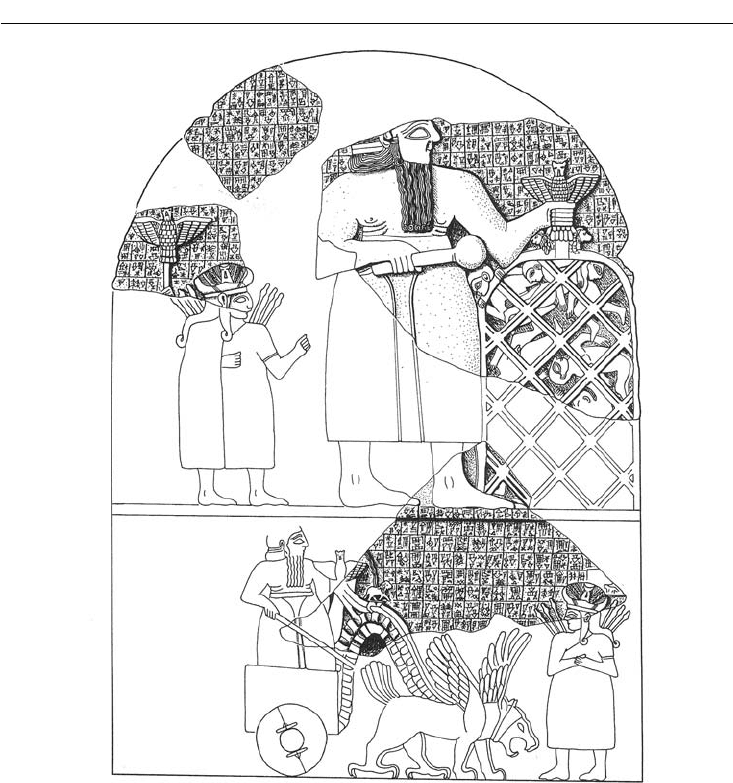

ings. One of the most striking of all ED “high temples” was the Temple Oval, uncovered at

Khafajeh (ancient Tutub), north-east of Baghdad in the Diyala River basin (Figure 2.12). Since

the identity of the god worshipped here is unknown, the modern name of the complex reflects

its most distinctive trait, the unusual oval contour of its outer walls. In addition to this “high

Figure 2.11b Reverse, Stele of the Vultures

44 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

temple,” the city of Khafajeh also contained an imposing complex of “ground-level” temples,

the main one of which was dedicated to the moon-god, Sin.

Although the Temple Oval was poorly preserved, with only a few brick courses of the ground

plan surviving, three stages of construction and remodeling during ED II and III could be docu-

mented. Before the construction of the walls, the entire sacred area, approximately 100m across,

was cleared to a depth of 4.6m and filled with clean sand. The excavator, Pinhas Delougaz of

the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, estimated the quantity of sand at 64,000 m

3

.

After this ritual preparation, intended to create a pure environment for the god’s residence, the

area was bounded by an oval wall. Plano-convex bricks were used, bricks with a flat bottom and

a curved top, a shape that enjoyed great popularity only in ED Mesopotamia. They were set

diagonally in a herringbone pattern: one course tilted to the right, the next course tilted to the

left, and so on.

An inner oval enclosed a rectangular court lined with rooms serving for workshops and for

storage. Such non-religious concerns in the heart of the temple complex remind us of the multi-

faceted concept of the temple as an economic and administrative as well as spiritual center. At

the rear of this court the temple proper stood on a platform. Only the outline of the platform

and a trace of the stairway leading up to it have survived. The temple plan is uncertain. It would

not, however, have repeated the familiar tripartite plan with exterior indentations; that type had

disappeared in early ED I. The reconstruction drawing presents a simple temple based on evi-

dence from a nearby city, Tell Asmar.

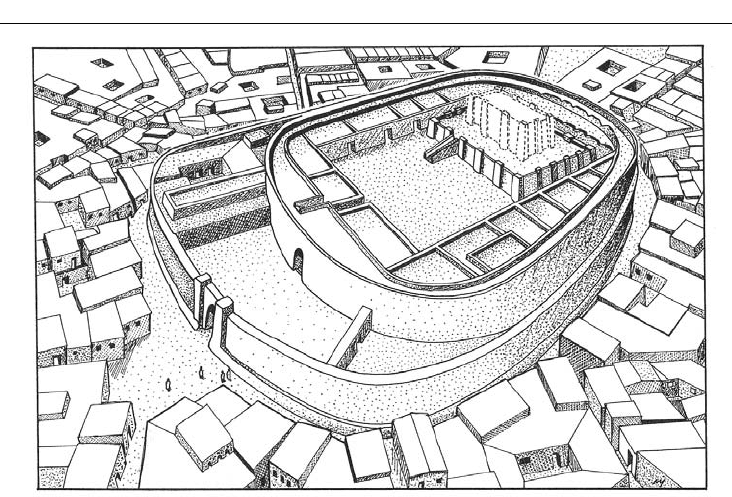

The decoration of the Temple Oval has entirely disappeared, but some idea of the elaborate

architecture ornament is supplied by a large bronze lintel discovered at another oval temple

complex, dated to ED III (ca. 2550

BC), at Ubaid. The lintel, 1.07m high, consisting of cop-

per sheeting over a wooden core, carries in high relief depictions of the ferocious lion-headed

bird Imdugud (also known as Anzu) flanked by two stags with spiky antlers (Figure 2.13). Such

Figure 2.12 The Temple Oval (reconstruction), Khafajeh

EARLY SUMERIAN CITIES 45

monsters had a magical protective role in Mesopotamian antiquity. This lintel, it is conjectured,

graced the top of the main doorway into the temple to the mother goddess Nin-Khursag. Frag-

ments of similar relief sculptures sheathed in copper have been assigned to other walls of the

temple. Other decorations included inlaid columns in the form of date palm trunks and friezes

inlaid on the walls. Because the building itself has disappeared, the exact deployment of the

decorations is not known.

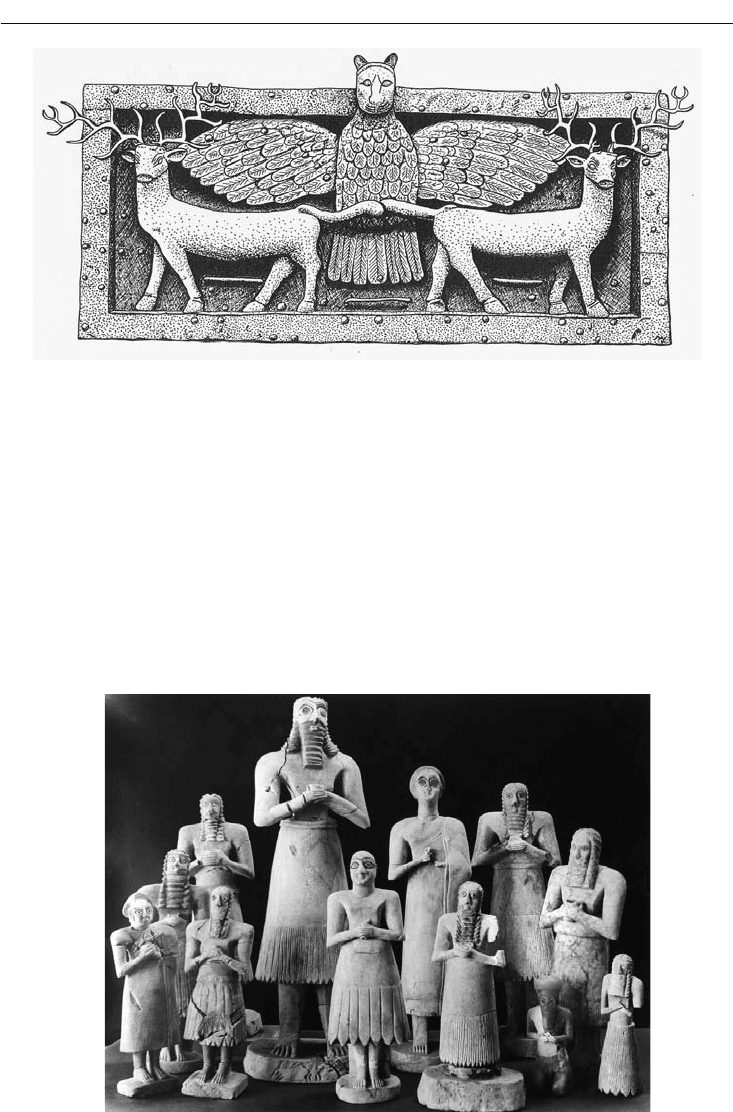

The appearance of Sumerian worshippers at such temples survives in sculpture, for example

in a group found at the Square Temple at Tell Asmar (capital of the ancient state of Eshnunna

of which Khafajeh was a part) (Figure 2.14). They date to ED II, ca. 2700 BC. According to

the inscriptions on similar examples of later (ED III) date, these statues are votives, that is, gifts

Figure 2.13 Bronze Lintel with Imdugud (Anzu) and stags, from Ubaid. British Museum, London

Figure 2.14 Worshippers, stone figurines, from Tell Asmar. Iraq Museum, Baghdad; and Oriental

Institute, University of Chicago

46 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

offered by worshippers to the deities. The tallest of the statues are 0.75m, half life-size. They

represent the worshippers themselves, not gods, all clasping their hands in front of their chest

in the proper position for prayer. The large eye sockets and grooves for eyebrows, filled with

bright white and black paste, shell and lapis lazuli, and the square shoulders and pointed elbows

give them a distinctive appearance. The women dress in a simple garment that passes diagonally

across the breast and is draped over one shoulder, whereas the men choose wool skirts with

fringe on the bottom. Priests can be recognized by their clean-shaven heads and faces. Lay peo-

ple also have distinctive hair styles: women feature a braid encircling the head with a knot in the

rear, while men wear their hair long and have squared beards. These squared beards which fall in

tiers will remain a favorite fashion throughout Mesopotamian civilization (see the Neo-Assyrian

reliefs of the first millennium BC). One wonders if the wave patterns of the beards resulted from

special treatment, such as curling with hot irons or waxing.

UR: THE ROYAL TOMBS

Ur is the most extensively explored of the great Sumerian cities, revealed notably by the excava-

tions conducted in 1922–34 by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley on behalf of the

University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania and the British Museum. Modern interest

in this ancient city has been sparked not only by Woolley’s discoveries, but also by the site’s apoc-

ryphal identification with Ur of the Chaldees, the home of the biblical patriarch Abraham.

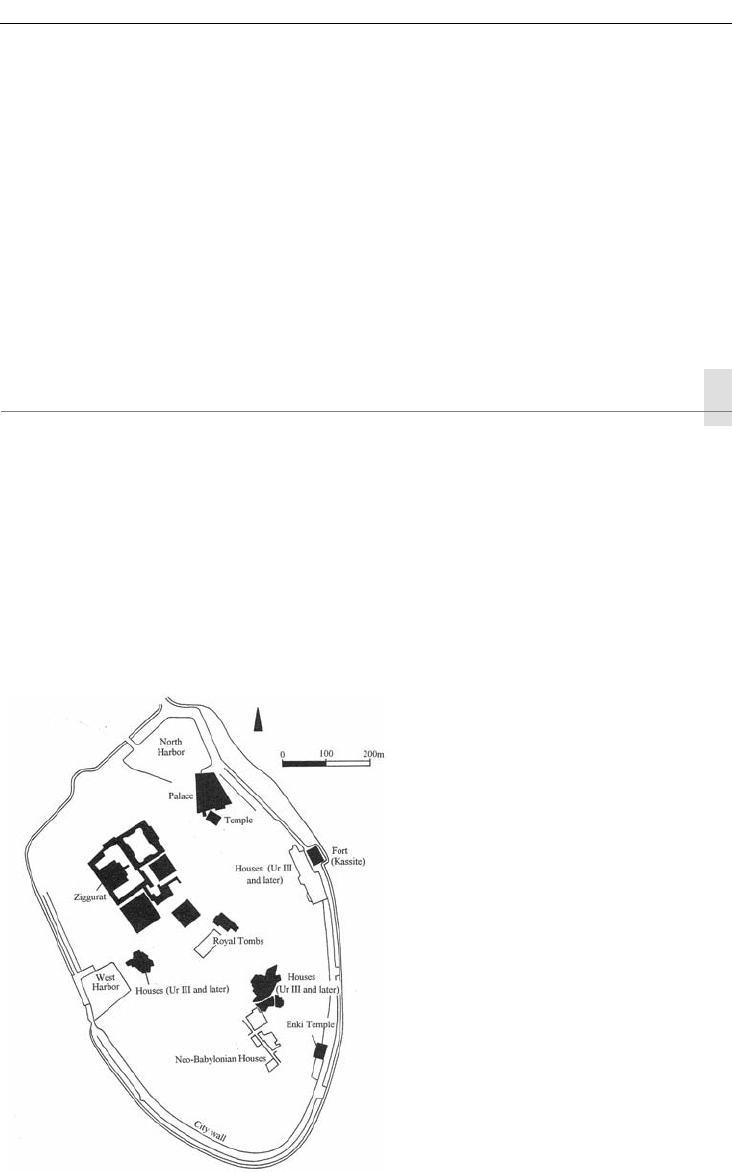

Like so many cities of southern Mesopotamia, Ur was inhabited for several thousand years,

from the fifth well into the first millennia BC. Here we shall examine the most famous part of the

ED city, the Royal Tombs. In the next chapter our attention will focus on aspects of Ur in a later

period, during the reign of the city’s greatest ruler, Ur-Nammu: the city walls, the city center with

its ziggurat, and the private houses (Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15 City plan, Ur

EARLY SUMERIAN CITIES 47

The sixteen Royal Tombs of the ED III period were among the earlier burials in a centrally

located cemetery containing some 2,000 interments ranging in date from Ubaid to Neo-Sume-

rian times. The names of some of the persons buried here are known, written on objects found

in the tombs: a queen or priestess Pu-abi (called Shubad by Woolley), and two kings of Ur,

Akalamdug and Meskalamdug. The unknown may well include high-ranking administrators or

religious figures.

The Royal Tombs, unique to Ur, are striking not only for the splendor of the grave offer-

ings and for the tomb construction, but also for the traces of the elaborate mortuary ritual that

included human sacrifice. In each tomb, the important person, on occasion with companions,

and a magnificent array of objects were placed in one or more burial chambers at the foot of

a steep ramp. The participants in the funerary procession lay neatly arranged on the ramp: the

remains of the draft animals in front of the wheeled vehicles they pulled and the skeletons of

soldiers and female attendants. Although their clothes had disintegrated, adornments of precious

metal survived. Tomb no. 1237, whose occupant remains anonymous, contained the largest

number of bodies: seventy-four, including sixty-eight women still wearing their finest gold jew-

elry. Did these attendants meet death willingly, with resigned acceptance? What purpose did they

believe they were serving? Such practices have been attested at no other city. Textual evidence

offers no convincing explanation.

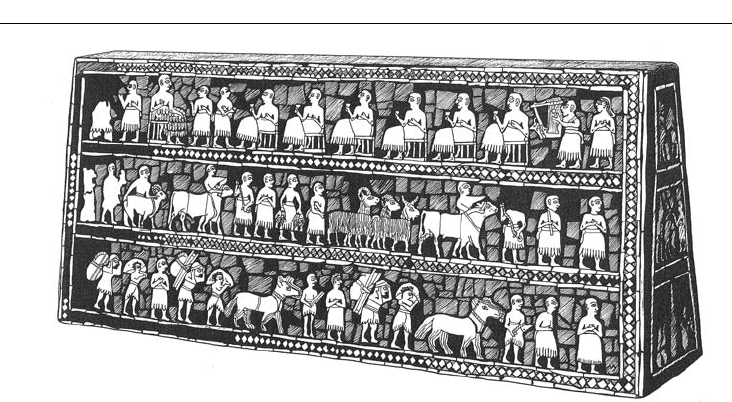

Grave goods: a bull’s headed lyre and the Royal Standard

Although Sumerian thieves had cleared out some of the graves, many funerary gifts remained

in situ, such as jewelry, vessels of gold and silver, musical instruments, weapons, game boards.

Shown here are two of the finds, a lyre decorated with a bull’s head and inlay on the sound box

and the so-called Royal Standard of Ur.

This lyre, the finest of several examples from the tombs, was discovered in the tomb of King

Meskalamdug (Figure 2.16). Although the wooden parts had rotted away, the shape of the lyre

was preserved in the ground. By pouring liquid plaster

into the cavity, the excavators could accurately reas-

semble the form and the non-perishable decorations.

Measuring 1.22m in height, the instrument consists of

a wooden sounding box on the bottom and an upright

section on either end, all inlaid with colored materials.

A horizontal bar across the top would have held the

strings running up from the sounding box, and tuning

pegs. The golden head of a bearded bull decorated the

front, perhaps an apotropaic image to ward off evil.

Such lyres were not just for show, for on one side of

the Royal Standard of Ur, a priest can be seen pluck-

ing happily on a virtually identical instrument.

The Royal Standard may itself have been an elabo-

rate sounding box for a harp or lyre, or, as originally

thought, a standard placed on a pole and carried

before the king in ceremonial processions (Figure

2.17). The wooden core measures ca. 20cm

× 45cm.

After preparing the surface with bitumen, a tar used

in antiquity as a sealant and glue, the artisan applied

Figure 2.16 Lyre (reconstructed), from

Ur. University of Pennsylvania Museum of

Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia

48 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

the mosaic, figures and borders of bits of shell against a blue background made of pieces of lapis

lazuli. The Royal Standard is notable not only for the fine preservation of its inlay, one of the

favorite crafts of the Sumerians, but also for its figural scenes, expressions of royal imagery. Each

side has three registers; the scenes are read as a continuous story from the lowest register to the

uppermost. The reverse, “War,” depicts the king, his infantry, and his chariots, with enemies

trampled, whereas the obverse, sometimes called “Peace,” shows banqueting, and the transport

of animals, agricultural products, and booty. Wheeled vehicles are first depicted earlier, in ED

I, typically as war chariots. The animals pulling the ungainly four-wheeled chariots shown in the

scene of “War” on the Royal Standard were thought to be onagers (wild asses). Recent research

in Syria and Palestine suggests they may instead be mules, a hybrid between donkeys and very

small horses. The horse was long considered to have been introduced into Mesopotamia in the

mid-second millennium BC, an import from Central Asia. The issue is now open for discussion.

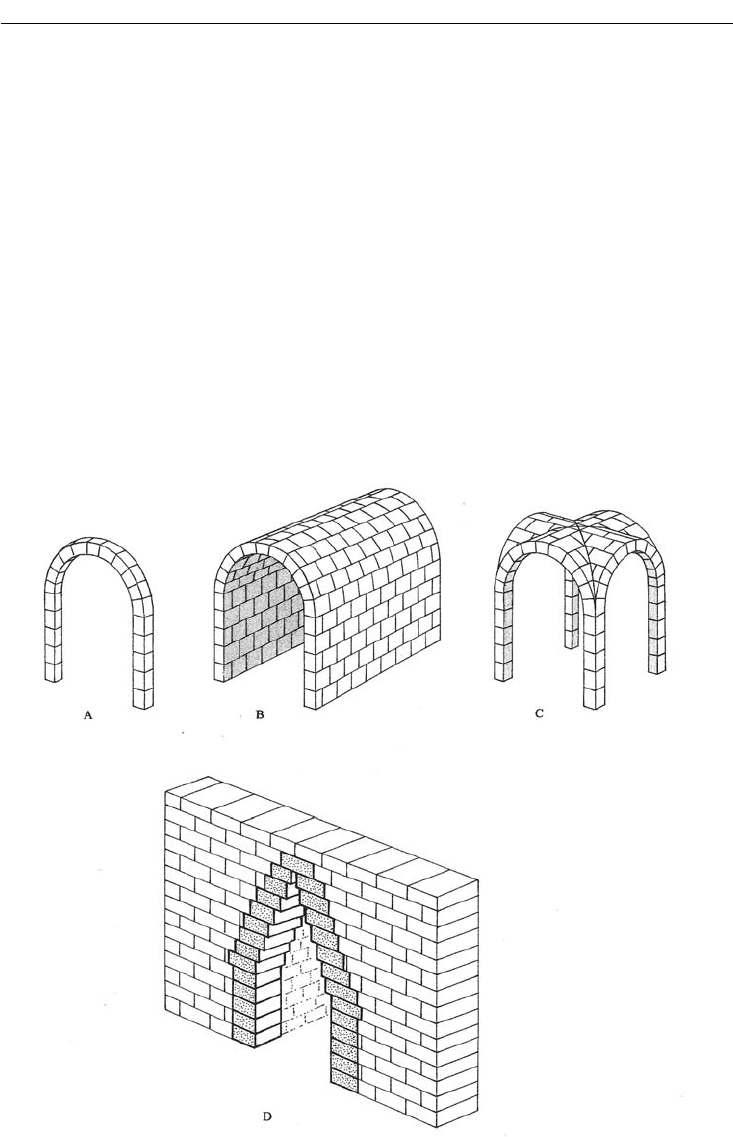

Roofing techniques: arches and vaults

The roofing of the tomb chambers is of particular interest, because evidence for the roofs of

Sumerian buildings is rare. Stout timbers, reed or palm frond matting, and a sealing of clay

would have created a sturdy roof for a house, strong enough to hold the weight of a person. The

same system could have been used for larger buildings, if interior columns divided the span of a

room into manageable dimensions. In certain cases a more elaborate roofing of mud bricks was

attempted. In the Royal Tombs of Ur, the chambers were vaulted or, rarely, domed with brick

or limestone rubble, using the technique of corbelling (see below). Valuable evidence for vaulting

techniques has come from excavations conducted in the 1960s at the second millennium

BC

site of Tell al Rimah, in north-west Iraq; well-preserved mud brick arches and vaults, some in

the pitched-brick technique, are essential components of a large temple of the early second mil-

lennium

BC.

The progression to the true arch and domical vault (= the dome) is one of the important archi-

tectural developments in the ancient Mediterranean and Near East and will be examined later in

Figure 2.17 “Peace,” the obverse of the “Royal Standard,” inlaid panel, from Ur. British Museum,

London

EARLY SUMERIAN CITIES 49

this book. The early techniques just mentioned, corbelling and pitched-brick, merit explanation.

But first, the distinction between an arch and a vault needs to be appreciated: an arch is a two-

dimensional span, covering a doorway or window, whereas a vault is three-dimensional, covering

a room. The principles of arch construction can often be applied to vaults.

In a corbelled arch, on each of the two sides each successive block projects further inward until

finally the two sides touch at the top (Figure 2.18d). If left by itself, the corbelled arch will even-

tually collapse: the weight pressing down toward the empty center of the arched space is not

sufficiently counterbalanced by the weight of one brick on top of another. To solve this prob-

lem, a counterweight needs to be placed on the outside, to press the outer edges of the bricks

downwards, to direct pressure toward the brick just below. If well incorporated into a sturdy

wall, a corbelled arch could stand. In contrast, vaults made in the corbelling technique never

stand alone, without counterweight, unless the space they cover is small (as in a small room of a

house). Good-sized corbelled vaults are underground, with a packing of earth around and above

the structure to provide the necessary counterpressure.

In the true arch as distinct from the corbelled, stones are specially cut in wedge shapes to fit

into one continuous curve (Figure 2.18a). The form and placement of the keystone, the wedge

Figure 2.18 Diagram: (a) true arch; (b) barrel vault; (c) groin vault; and (d) corbelled arch

50 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

at the top of the arch, illustrates how the pressure from each stone is not directed exclusively

downwards, but also to the side. The vertical struts that support the arch need to be reinforced

in order not to buckle outwards, but the arch itself should not collapse. As with corbelling, the

principles of true arch construction can be extended to three-dimensional forms, the vault (two

are important in Mediterranean antiquity, the barrel vault and the groin vault: Figures 2.18b and c,

respectively) and the dome (a hemispherical vault).

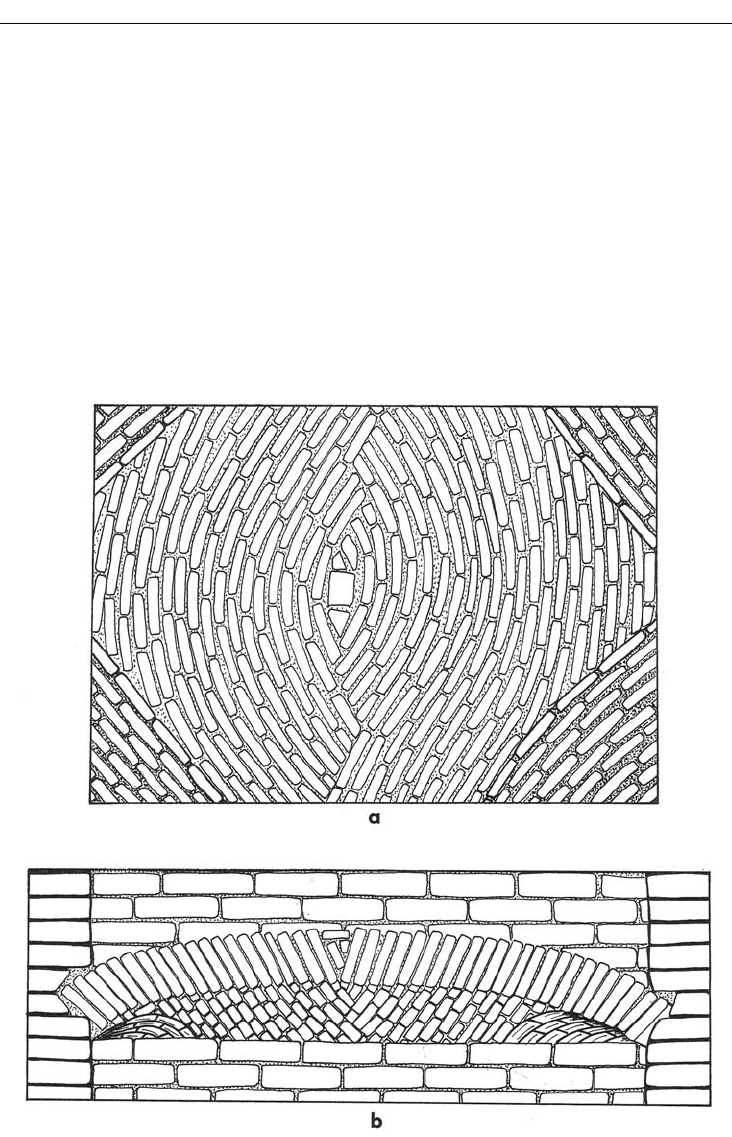

The pitched-brick technique of roofing falls somewhere between the above two methods

(Figure 2.19a–b). The bricks are not specially cut into wedge shapes, nor are they placed flat one

on top of the other. Instead, each successive brick is tilted slightly in order to form a curved line.

The extra space at the top is filled with fragments. Although much more fragile than a true dome,

such a structure can stand on its own.

Figure 2.19 Diagram: The pitched brick vault: (a) view from below; and (b) in cross section

EARLY SUMERIAN CITIES 51

SUMMARY

By 2350 BC, the city was already firmly established in southern Mesopotamia as the center of social,

economic, and political life. Owned by the gods, administered for them by kings, Sumerian cities

controlled their regional agriculture and water supplies, promoted industries, and participated in

the long-distance trade that ensured provisions of raw materials unavailable locally. The cities

themselves were fortified nuclei located on agricultural land and their life-giving watercourses.

Dominating the city, the temple of the tutelary deity was the city’s original religious, economic,

and administrative center. During the ED period the royal palace first appeared, the focus of the

rising rival power of the earthly ruler. The town would be further divided into neighborhoods by

canals, streets, and walls, but not according to any general pattern repeated from one Sumerian

city to the next. Social and economic aspects of the early Sumerian city include – and here we can

remind ourselves of Childe’s list of ten criteria for the true city – a hierarchical society; a variety

of non-agricultural occupations; the development of scientific observation, especially to assist

agricultural practice; an expanded range of monumental architecture; figural art with extensive

royal and religious imagery; and writing, by 2350 BC recording not only the economic data that

inspired its initial development but also myth, ritual, and historical and contemporary events. If

the Neolithic period gave rise to the embryonic city, in southern Mesopotamia in the fourth and

third millennia BC the full-fledged city was born.