Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

22 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

The fourth and last has been called the “Terrazzo Building.” Its large single room featured a

well-prepared floor, a very hard layer 40cm thick of polished cobbles and pinkish lime, this last

made by burning limestone. Linear patterns were created by white stones set into the floor. Such

“terrazzo” floors have been found elsewhere, but after this period the technique was forgotten

until the Iron Age some 5,000 years later.

In Subphase 6, the Large-room Building subphase, the character of the village changed dramati-

cally. The settlement became smaller. Communal buildings were absent, and the Plaza was used

as a refuse dump. Houses consisted of one or two large rooms only. Clearly some major social

change happened at Çayönü; further evidence for change has come from the economic data, as

noted below.

The Pottery Neolithic (Phase II), ca. 6000–5000 BC, is defined by the sudden appearance of pot-

tery, a technique assumed to be imported from outside because no beginning, experimental

stages have been identified. The settlement continues from before, without dramatic break, but

now the neat arrangement of buildings originally established during the Grill Plan subphase

(Subphase 2) is replaced by the clustering of irregularly shaped houses along narrow streets.

Communal buildings continue to be absent.

As for the economy of Neolithic Çayönü, the excavations have documented the evolution of

a village economy from food collection into food production over this continuously inhabited

period of 3,000 years. During Subphases 1–5, the villagers depended on the collecting of wild

plants and the hunting of wild animals. The cultivation of pulses, lentils, and vetch, followed by

the addition of Einkorn wheat, offered supplements to the diet. Only in the later PPNB, in Sub-

phase 5, did this pattern change. Domesticated sheep and goat then appeared in great numbers,

becoming a dietary staple. The hunting of wild animals diminished considerably.

Çayönü has yielded striking evidence for early metallurgy. Native copper and malachite, found

nearby, were worked in Subphase 2, with an intensification in metallurgy in Subphases 3 and

4; subsequently, metalworking declined. The ore was hammered unheated to create such tools

as pins, hooks, and drills – a simple start to a technology that would later prove so important.

Annealing was also practiced: heating, but not smelting, of copper lumps to shape them more

easily. The finds at Çayönü count among the earliest known use of metal in the Near East.

Other crafts were practiced as well, such as bead making and weaving. A cloth impression

made of domestic linen gives early evidence in the Near East for the craft of weaving. The pres-

ence of obsidian and sea shells, used for tools and decoration, indicates long-distance trade.

Not known is whether or not the artisans of Çayönü practiced their crafts full time. If they did,

they fulfill Childe’s third criterion for the city, “occupations other than farming.” Other factors

on Childe’s list present at Çayönü may include social stratification (as noted above) and monu-

mental public architecture. But other elements of his definition are absent. What the excavations

of Çayönü have revealed to us is the gradual appearance during the Neolithic period of certain

features of social life that will eventually coalesce into the fully developed city of the later fourth

and third millennia BC.

GÖBEKLI

.

TEPE: AN EARLY NEOLITHIC CEREMONIAL

CENTER

A sensational discovery of recent years that raises fascinating questions about the role of ideology

in the material world of early Neolithic people is the ceremonial center at Göbekli Tepe, 15km

north-east of S¸anlıurfa in south-eastern Turkey (Figures 1.7 and 1.8). Excavated since 1995 by a

NEOLITHIC TOWNS AND VILLAGES 23

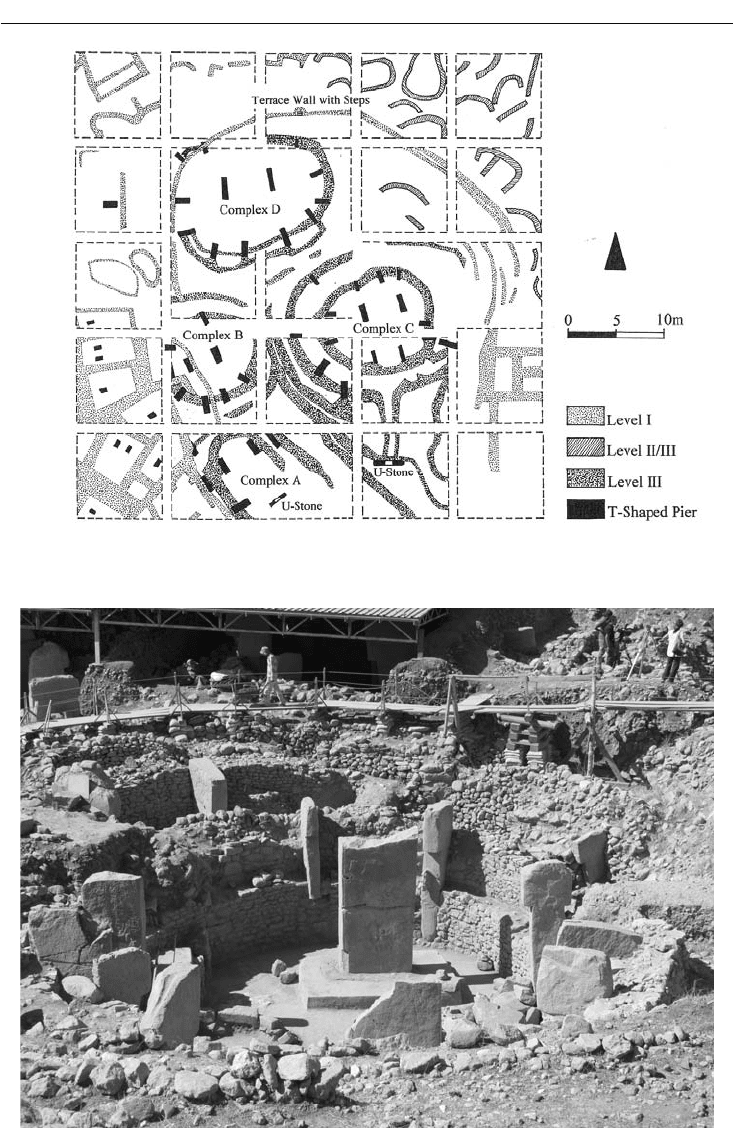

Figure 1.7 Plan, Central area (in 2007), Göbekli Tepe

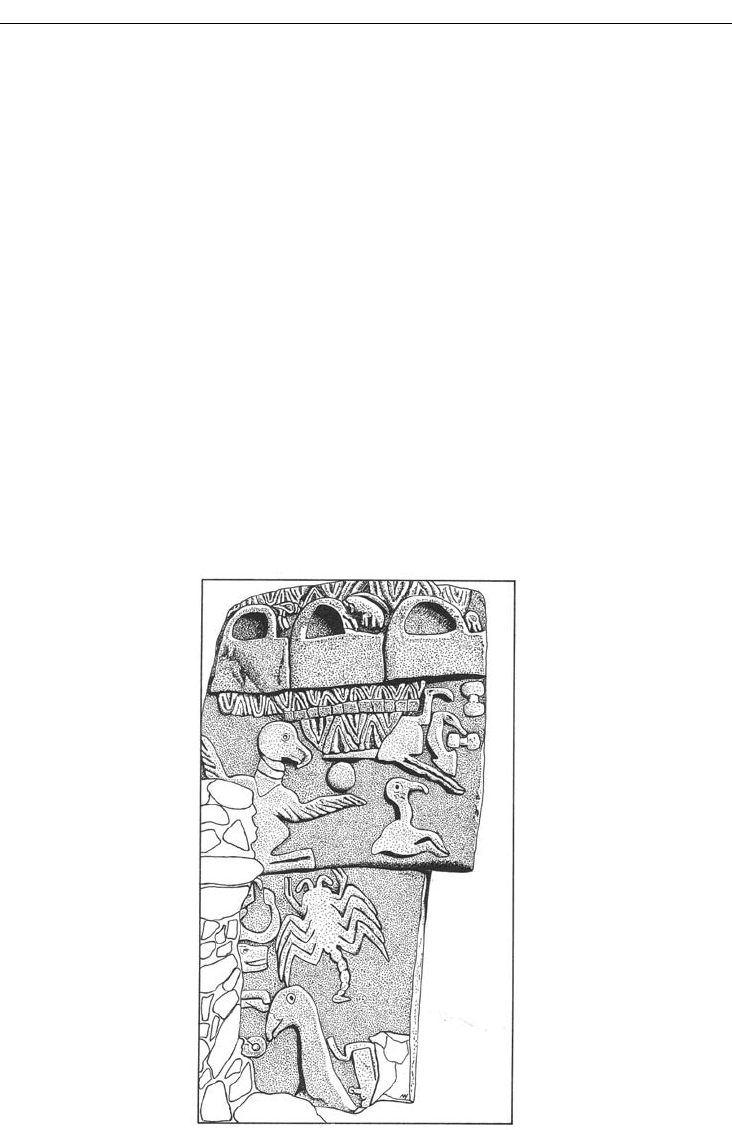

Figure 1.8 Complex C (foreground) and Complex B, Göbekli Tepe

24 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

team from the German Archaeological Institute and the S¸anlıurfa Museum under the direction

of Klaus Schmidt, this dramatic hilltop site consists of a series of at least twenty circular rooms

placed on its south and west slopes. The rooms are well preserved because they were deliberately

“buried” with fill up to the original height of the building.

The rooms are formed by a stone wall, sometimes by a series of concentric walls. In some,

large, monolithic T-shaped stone piers are placed at right angles in the wall as reinforcements

and roof supports. Two piers, also monolithic, T-shaped, very tall, and rectangular in section, are

typically found in the center of a room as additional supports for the roofing. These rooms may

have been embedded in the ground, Schmidt has speculated, with entrance from the roof, like

kivas, the subterranean ceremonial rooms of the Pueblo Indians of the south-west United States.

The largest of the excavated rooms is Complex C, measuring in diameter 12m (interior) to 30m

(the outermost of its four concentric walls). Its piers are 5m in height.

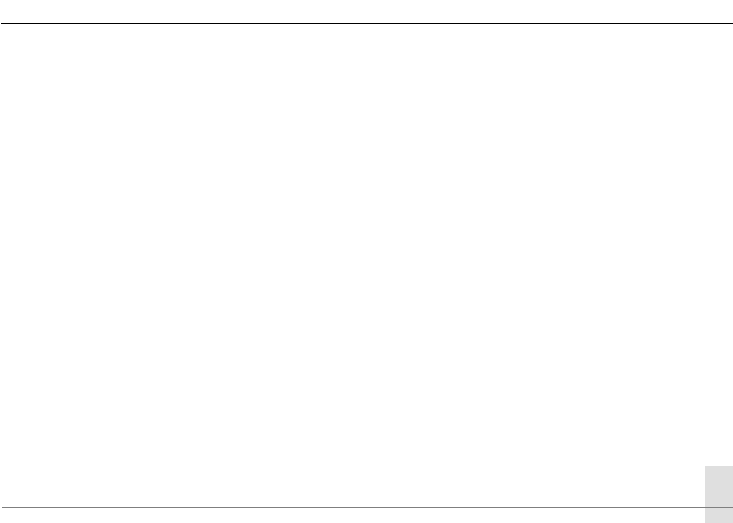

The central piers and many of those placed in the enclosing walls are typically decorated with

relief sculpture depicting a frightening array of predatory animals, birds, and insects, such as

lions, foxes, vultures, snakes, and scorpions (Figure 1.9). Some piers, with long, thin arms carved

on each side, the hands meeting on the narrow front side, seem to represent humans. The mean-

ing of these images must be connected to the rituals celebrated and the ideology that underlay

them, whatever they may have been.

The absence of any established settlement, at least in the early level (Level III) represented by

these circular complexes, makes it clear that this was a cult or ceremonial center. Beyond that,

Figure 1.9 Partially excavated Stele from Complex D, Göbekli Tepe

NEOLITHIC TOWNS AND VILLAGES 25

much about Göbekli Tepe is still uncertain. The circular complexes were built at different times,

it is thought, but at what intervals and by whom? The commanding view of the countryside from

this hilltop suggests that the center was developed and patronized by people from a large region.

Who were these people? Were they villagers, nomads, or hunter-gatherers? Who organized the

huge amount of labor involved in the quarrying, carving, and construction?

As for the chronology of the site, Level III is placed in PPNA (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A; see

above, under “Jericho”).The subsequent Level II, with smaller circles, small oval huts, and rect-

angular houses, is assigned to PPNB. Based on C14 results, Schmidt has dated Level III to the

late tenth millennium BC, Level II to the nineth millennium BC. These absolute dates are contro-

versial; for some scholars, they seem too early.

The only site yet known with comparable features, such as monolithic piers with sculpted

images, is Nevalı Çori, a PPNB settlement with cult center located on the east shore of the

Euphrates River. Excavated in 1993, this site now lies below the lake formed behind the Atatürk

Dam. The distance between Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori is 70km. It may be that within this

radius from Göbekli Tepe, other sites with similar cultic features once thrived in the Early

Neolithic period. Further information is eagerly awaited.

ÇATALHÖYÜK

Trends of the Neolithic period discussed above – developments in town planning, architecture,

agriculture (including animal husbandry), technology, and religion – come together dramatically

at Çatalhöyük (western Turkey, near Konya), in twelve well-preserved building levels dated ca.

6500–5500 BC. The site lies in the Konya plain, in a favorable environmental setting. Geomor-

phological study has revealed that in Neolithic times the town stood near a river, a lake, and

marshes, with hills not far off. The site consists of two adjacent mounds, east and west. The east-

ern mound contains the Neolithic remains that interest us here, whereas the western mound has

later occupation, Early Chalcolithic. The eastern mound measures over 13ha, unusually large for

this period. Only 0.4ha was excavated in the early 1960s by James Mellaart of the British Institute

of Archaeology at Ankara, but current investigations, begun in 1993 under the direction of Ian

Hodder, now at Stanford University, are expanding the area exposed.

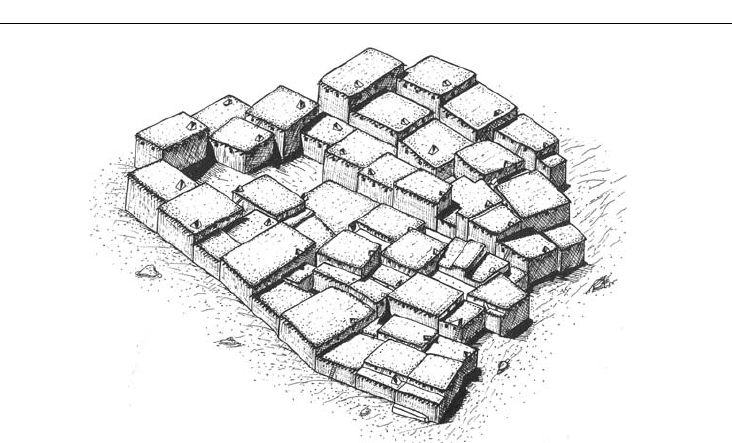

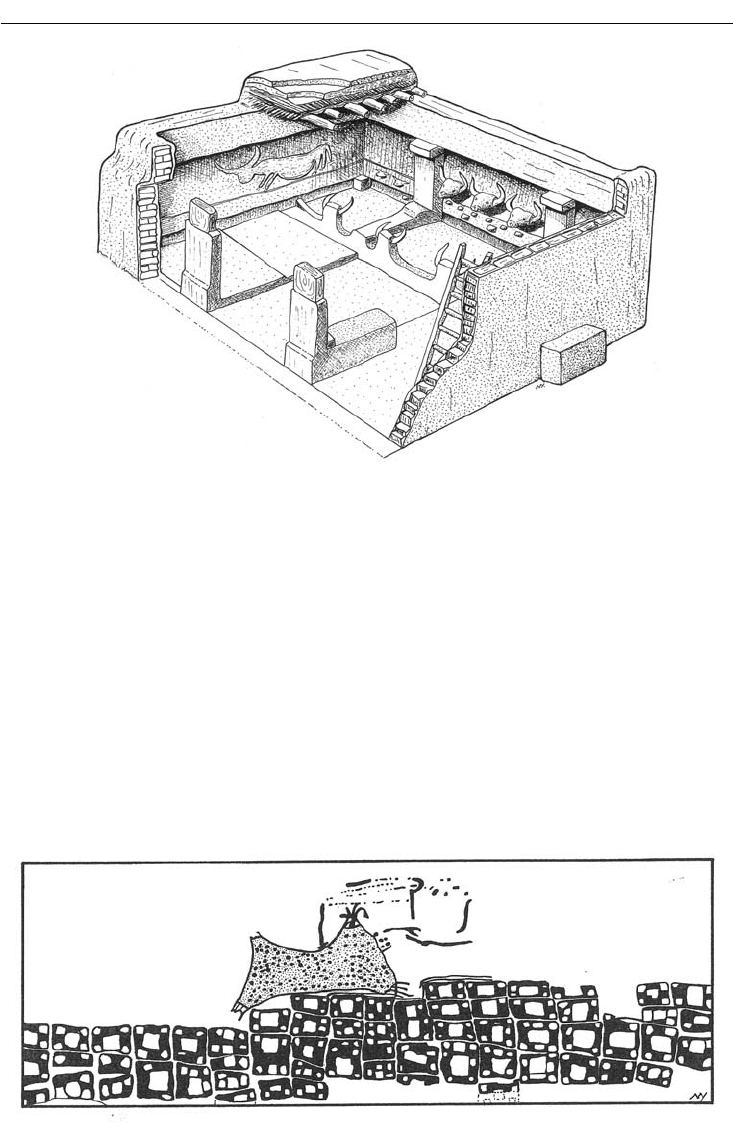

The appearance of the town recalls the Native American pueblos of the south-west United

States and is otherwise unattested in the Ancient Near East (Figure 1.10). Houses were made

of mud brick, often with a framework of wooden pillars and beams. The flat roofs consisted of

clay on top of a network of wood. The houses clustered together, their walls touching those of

their neighbors. Although small courtyards connected by streets lined the edges of the excavated

area, within the cluster courts existed but streets did not. People entered houses from the flat

rooftops, descending to the floor by means of a ladder. Since the town lay on sloping ground, the

height of the roofs varied. Could this honeycomb arrangement have been intended as a system of

defense? Was it used throughout the site, or just in this excavated neighborhood? Some of these

questions may be answered by the new excavations.

The rather small interior of a typical house consisted of a main room with an adjacent storeroom,

together making up a maximum 30m

2

of floor space. It is hypothesized that small windows high

up in the walls provided light and, together with the usual hole in the roof, allowed smoke from

the hearth and ovens to escape. Each house contained at least two low platforms, with a raised

bench at one end of the main platform. The built-in “furniture” must have led to a division of the

room for different purposes, for work or for leisure. In addition, the bones of the dead were buried

26 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

beneath these platforms, perhaps after the bodies had been exposed outside the settlement, the

flesh removed by vultures. One exceptional burial contained the remains of a young woman hold-

ing a plastered skull whose face was painted red. As at Jericho, the presence of ancestors beneath

the floors of a house may have been a way for early agriculturalists to mark eternal possession of the

land, to legitimize their occupation. Such intramural burials contrast sharply with the later Classical

practice of scrupulously keeping cemeteries outside the city walls: for the Greeks and the Romans,

the dead menaced and polluted the land of the living and had to be kept at a distance.

Organic remains were unexpectedly well preserved at the time of Mellaart’s excavations,

thanks to the high water table. Recently, because of developments in the local farming industry,

the water table has dropped dramatically; archaeological preservation may be adversely affected.

Plants grown at Çatalhöyük included cereals (such as barley and wheat), nuts (pistachios and

almonds), and legumes (peas and bitter vetch). The largely vegetarian diet was supplemented by

beef, sheep, and goat. Analysis of the cattle bones has revealed that cattle were domesticated,

among the earliest examples yet known from West Asia. Wild animals hunted include red deer,

boar, wild cattle, and sheep (although traces of woollen textiles show the presence of domesti-

cated sheep, wool being a product of domesticated animals).

The residents of Çatalhöyük included accomplished craftsmen. Beautiful pressure-flaked

obsidian spearheads and arrowheads and flint daggers attest to the skill of the makers of chipped

stone tools. The finding of lead pendants and copper slag indicates knowledge of metallurgy.

Pottery, always handmade without recourse to a potter’s wheel, occurs from the earliest levels,

but finds of wooden bowls, cups, and boxes remind us that containers of normally perishable

materials (skins and basketry as well as wood) played an equally important role in daily life. Frag-

ments of woollen and perhaps flaxen textiles, like the wooden items preserved by burning, are

unusually early examples. Patterns used in weaving may be depicted in the wall paintings here.

Çatalhöyük participated in an extensive trade network, with obsidian a key commodity.

Much obsidian was found here, not surprising with nearby sources in central Anatolia, near the

volcanoes Karaca Dag˘ and Hasan Dag˘. Items from farther distances include Mediterranean sea

shells, valued especially as beads, and turquoise from the Sinai.

Figure 1.10 Houses (reconstruction), Çatalhöyük

NEOLITHIC TOWNS AND VILLAGES 27

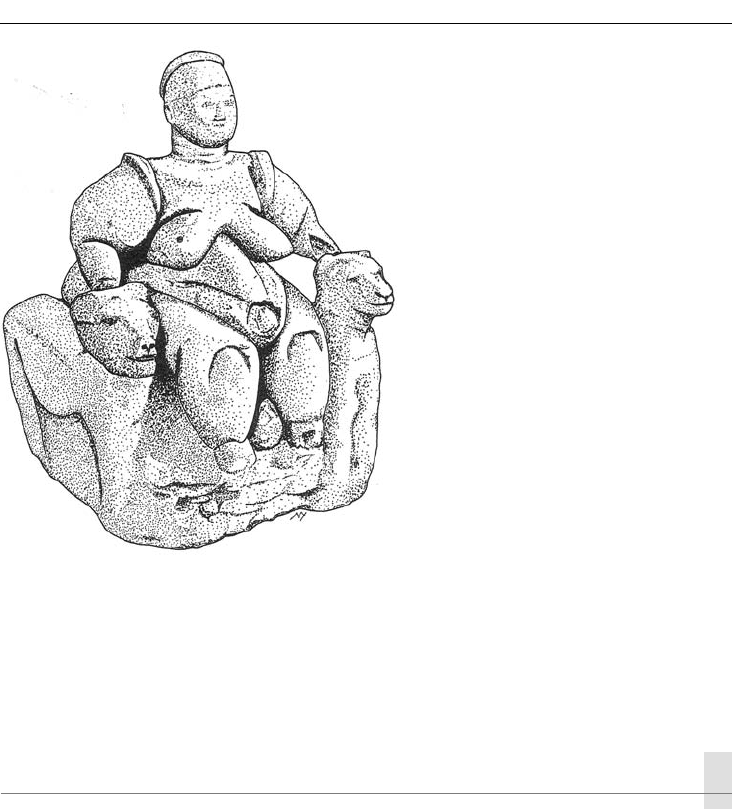

Evidence for religious practices is abundant. Over forty houses scattered through the many

building levels have been identified as shrines. While their plans do not differ from those of

regular houses, their decoration does. Craftsmen appointed these particular rooms with wall

paintings, relief sculpture, free-standing figures, and the actual horns of bulls and caprines and

jaws of foxes (Figure 1.11).

The wall paintings are of exceptional interest for their depictions of life in a Neolithic town.

Some walls have up to 100 layers of plaster, any of which might bear paintings – quite a chal-

lenge for the conservators. The technique of painting consisted of natural pigments mixed with

fat and applied on a background of white plaster. Subjects included the textile patterns already

mentioned, vultures attacking headless humans, cattle and deer hunts, and wild bulls relent-

lessly pursued by humans. One wall painting shows a stylized depiction of what may be a town

beneath an erupting volcano (Figure 1.12). Certain paintings were three-dimensional, reliefs built

Figure 1.11 House shrine (reconstruction), Çatalhöyük

Figure 1.12 Erupting volcano and town, wall painting, Çatalhöyük. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations,

Ankara

28 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

up from plaster. They depict bull or ram

heads (often with real horns incorporated

into the relief), occasionally leopards, and

a bear (formerly identified as a female

figure).

Free-standing figures similarly empha-

size the magical power of animals and

the desire for fertility. The figurine of a

massive woman (a goddess?) expresses

these beliefs to great effect (Figure 1.13).

Seated between two leopards (or pan-

thers), the woman is in the process of

giving birth. For ancient men and women

her obesity must have denoted abundant,

dependable food sources. Her prosperity,

her fecundity, and her mastery over wild

animals made her a symbol of much that

Neolithic people wished to attain.

To reconstruct the religious practices of the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük, we must rely on anal-

ogy with practices attested for later literate cultures and for those recorded by modern ethnogra-

phy. The striking images provided by the paintings and sculpture of Çatalhöyük tempt us to be

concrete in our interpretations. But we should be cautious. We must keep reminding ourselves

that the beliefs of people who lived 7,500 years ago still lie largely in shadow.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHIEFDOMS AND STATES

Çatalhöyük has seemed so remarkable in part because when it was initially excavated, its cultural

context was largely unknown, with little research available to evaluate contemporary settlements

in the area. Subsequent projects in central and south-eastern Turkey (such as Çayönü), Syria,

Iraq, and Iran have been fi lling in the picture. Nonetheless, Çatalhöyük, with its exceptional

preservation, gives us in a still distinctive way an idea of what other Neolithic towns and villages

may have looked like.

With the abandonment of Çatalhöyük in the mid-sixth millennium BC, the striking innova-

tions of central Anatolia came to a halt. Villages continued in the region, but for important

developments our focus shifts eastward to Mesopotamia. The next 2,000 years, the Halaf and

Ubaid periods, witnessed the gradual evolution of the Neolithic communities into chiefdoms

and states, both centralized political systems, culminating in the great urban civilization of the

Sumerians. A chiefdom is a political system in which a single ruler, a chief, exercises authority

over two or more local groups, his power distributed downward through a ranked hierarchy of

subordinates. The state is a more formal system, with power invested in a centralized govern-

ment, a combination of economic, military, legal, and ideological institutions. The state is able to

Figure 1.13 Seated fat woman (goddess?),

terracotta figurine, Çatalhöyük. Museum of

Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara

NEOLITHIC TOWNS AND VILLAGES 29

regulate its affairs in an impersonal way, and can use force, can mete out punishments in order

to support its decisions. Social stratifi cation is a characteristic feature of the state, as indeed it is

of the chiefdom.

Although the precise nature of the development of Near Eastern society during the Halaf and

Ubaid periods is controversial, the broad outlines seem clear. Social organization was varied. In

some towns an egalitarian society was the norm, with no groups holding special privileges, but

elsewhere, economic and social hierarchies emerged, whereby some members of the community

enjoyed more status, privileges, and possessions than others. Eventually hierarchy would prevail.

Management of food sources seems to have been responsible for this, with excess production,

which can be stored and sold or traded, providing accumulated wealth and power for some.

Religion may have offered an ideological justifi cation for such inequality. These periods were

marked in addition by innovations in technology (wheel-made pottery, sheet metal), transpor-

tation (boats with sails), and agriculture (tree crops). Trade networks continued, as the broad

distribution of Halaf and Ubaid pottery indicates, from Mediterranean Turkey to Iran. Little by

little the technological, commercial, and social world of the Ancient Near East was preparing

itself for the rise of full-fl edged cities.

CHAPTER 2

Early Sumerian cities

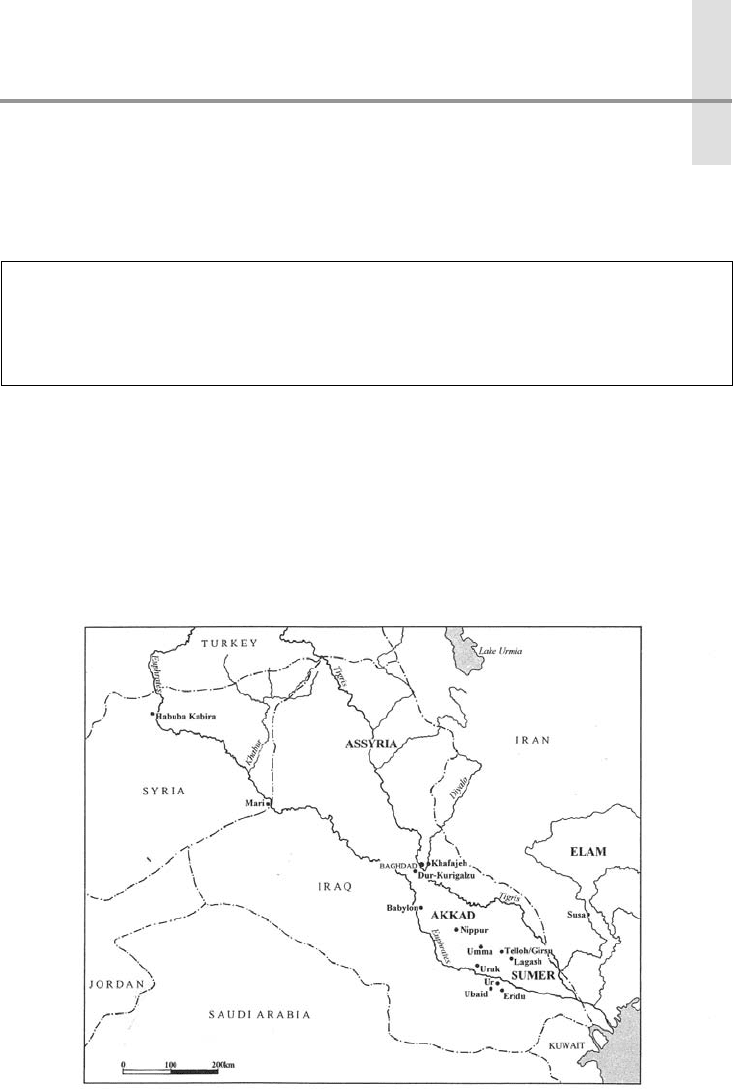

The first cities in the Near East–Mediterranean basin appeared in southern Mesopotamia, or

Sumer, the creation of a people we call the Sumerians (Figure 2.1). We have seen that environ-

mental changes in south-west Asia during the previous 5,000 years led to human control over

food production; with this mastery came major social changes, including fixed settlements. The

socio-economic development of these towns and villages is marked by the gradual appearance

of the ten criteria proposed by Childe as a mark of the true city. All ten factors finally emerge in

Sumer during the later fourth millennium BC.

Ubaid period: ca. 5000–3500 BC

Protoliterate (Uruk) period: ca. 3500–2900

BC

Early Dynastic period: ca. 2900–2350 BC

Figure 2.1 Mesopotamia: Bronze Age cities

EARLY SUMERIAN CITIES 31

This chapter will explore early Sumerian cities. We will want to ask why true cities originated

in southern Mesopotamia, a small region that did not figure in the Fertile Crescent and the Ana-

tolian–Zagros highlands, areas so important for the domestication of plants and animals. What

factors led the Sumerians to develop writing, the tool that propelled their settlements into the

rank of “city”? What characterized the Sumerian city, and how did it compare and contrast with

the Neolithic towns presented in Chapter 1? As examples, we shall inspect in particular the city

of Uruk and its northern colony at Habuba Kabira. Aspects of two additional cities will also be

examined: the Temple Oval, an important religious complex at Khafajeh; and the Royal Tombs of Ur,

a spectacular group of burials from the Early Dynastic III period, found intact. But first, before

we turn to Uruk, some background information about the Sumerians is needed.

THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT

The Sumerians, the known inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia from the fourth into the early

second millennia BC, are so called after the ancient Akkadian name for this region, “Shumer.”

Thanks to their writing, invented during the fourth millennium BC, far more is known about the

Sumerians than about their anonymous predecessors of the Neolithic age. The survival of the

clay tablets on which they wrote together with the remains of their cities allow us to trace with

greater confidence the increasing complexity of society in the ancient Near East.

The Sumerians stand alone in human history. Their language has no known relatives, and their

architecture and artifacts do not indicate ethnic ties with cultures of other regions. The continu-

ity of the material remains at their cities suggests, however, that the Sumerians had already settled

in southern Iraq in the later Neolithic period, at the end of the sixth millennium BC, well before

they developed the art of writing. This era of the earliest known settlements in the region is

called the Ubaid period, named after a site that has yielded a good sample of these early remains.

Subsequent periods are the Protoliterate or Uruk period (when the city of Uruk was dominant);

then the Early Dynastic period, divided into three parts (abbreviated as ED I, II, and III), during

which the Sumerian city-states became increasingly prosperous.

Cities are a distinctive feature of the Sumerians. Indeed, the independent, self-governing

city was their basic political unit. In this respect Sumer resembles ancient Greece, as we shall

see. Geography seems not to be the determining factor in this political development, for the

landscape of Sumer is flat, its terrain marked only by rivers and canals, whereas Greece is

divided by mountains and valleys. Instead, religious reasons seem responsible. Each Sume-

rian city-state nominally belonged to a god or goddess. The temple, the house of the divinity,

was thus the focus of both ritual and economic activity. It also became the regional admin-

istrative center. Each town that grew around such a temple was entrusted, on behalf of the

presiding deity, to the care of a mortal king (lugal, in Sumerian) or viceroy (ensi). Kingship first

began in the city of Eridu, according to Sumerian myth. The institution was later copied and

spread to other towns. The city-state, then, originated in remote, heroic times, the work of the

gods; the divinely sanctioned city-state would be for the Sumerians the basic unit of political

organization.

Rivalries between cities grew intense in the Early Dynastic period, thanks to territorial disputes

in this region where agricultural land was precious. Warfare drove people from the countryside

into the cities, now well protected with serious fortifications. No one city gained the upper hand.

Instead, a certain balance prevailed, resulting in the reinforcement of the city-state as the basic

political, religious, and social unit. Indeed, some thirty cities were federated in a league nominally