Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 1

Neolithic towns and villages in

the Near East

Urbanism is a recent phenomenon in the long history of humankind. If we subscribe to Childe’s

ten-point defi nition of a city (see Introduction), then cities proper, with all ten criteria pres-

ent, began in the fourth millennium BC in south-western Asia. These cities did not spring from

nowhere, however, but developed from the experiences of towns and villages established in

ecologically favored locations throughout western Asia during the previous 5,000 years. With

the fi nal receding of the glaciers around 10,000 BC, a warmer, moister climate was established

that proved favorable for a radical change in human social and economic development. This new

era, known as the Neolithic period, is the time when men and women fi rst organized themselves

in fi xed settlements and brought the reproduction and exploitation of plants and animals under

their control. Many of Childe’s ten characteristics of a city fi rst appeared in the towns and villages

of this long period.

The true city, then, had a long gestation. After considering first the physical world of the

Ancient Near East and then the nature of Neolithic food production and its consequences for

human habitation, this chapter will present four sites that illustrate the development of towns

during this important era: Jericho (in Palestine), Çayönü, and Çatalhöyük (both in Turkey), and

Göbekli Tepe (also in Turkey), a ceremonial center surely of larger regional significance.

GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, AND THE NEOLITHIC

REVOLUTION

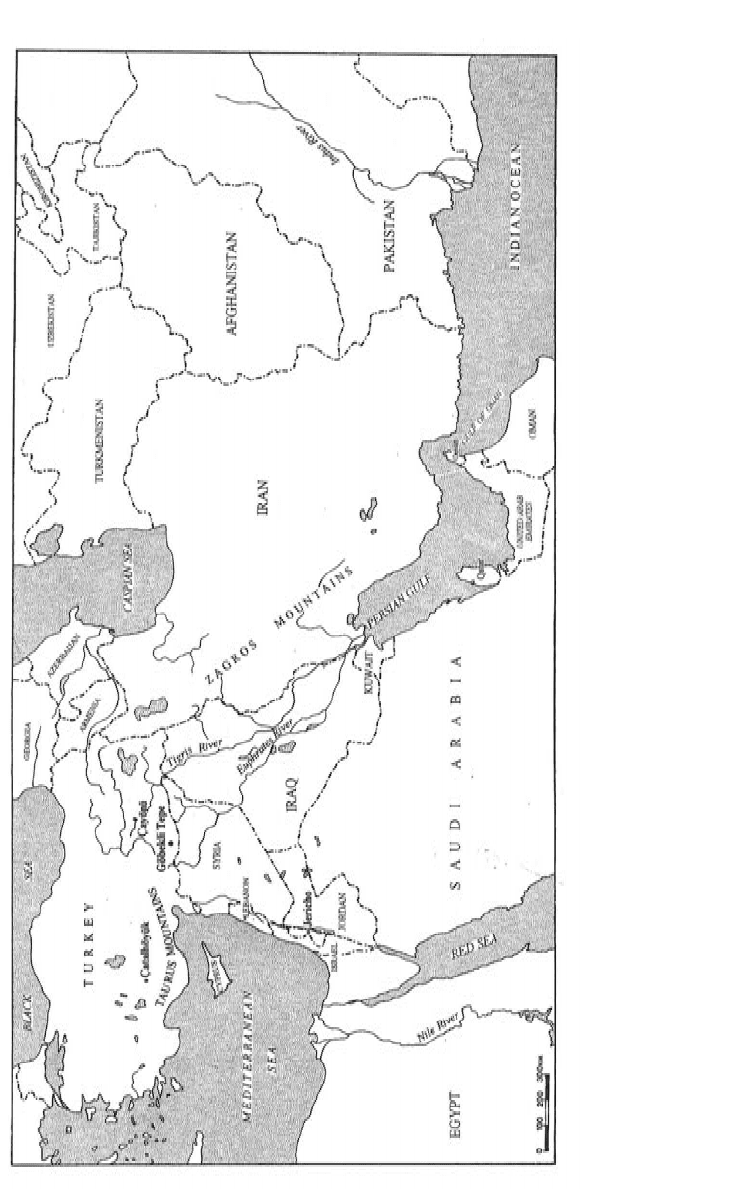

The Ancient Near East includes cultures stretching from Turkey to Pakistan (Figure 1.1). This

large area contains a variety of topographic and climatic zones: alluvial lowlands, uplands, moun-

tains, and desert. In the heart of the Near East lies Mesopotamia, the land between the two great

rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates. This region corresponds with modern Iraq, north-east Syria,

and south-east Turkey. The Euphrates, the longer of the two rivers, makes its leisurely way down

from the mountains of eastern Turkey across Syria and southwards through Iraq. The Tigris also

originates in Turkey, but follows a swifter path to the south. The two rivers meet in southern Iraq

and flow together to the Persian Gulf in a marshy waterway known as the Shatt al-Arab.

Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods: ca. 35,000–8550 BC

Neolithic period in the Near East: ca. 8550–5000

BC

Halaf and Ubaid periods: ca. 5000–3500 BC

Figure 1.1 The Near East: Neolithic towns

NEOLITHIC TOWNS AND VILLAGES 15

The southern half of Iraq is flat, its climate hot and dry. Farmers depend on irrigation from

the rivers, not on rainfall. This is the area in which Sumerian civilization flourished in the fourth

and third millennia BC.

The Taurus Mountains run east–west, crossing southern and eastern Turkey, northern Syria,

and northern Iraq, and link with the Zagros Mountains of western Iran. Beyond the mountains

lie great plateaus: the Anatolian to the north of the Taurus, and the Iranian to the east of the

Zagros. The remote mountain regions provide the snow that feeds the great rivers of the Near

East. The difficult terrain has discouraged social and economic unification, although trade and

movement of peoples can be active. The mountain people have always been autonomous and

independent, and throughout antiquity, just as today, have often annoyed or terrorized the estab-

lished cultures of the lowlands. The hostile environment of the desert has nurtured similarly

free-spirited peoples.

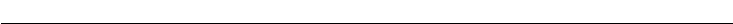

Between mountains and lowlands lie the uplands, or foothills. This zone, which forms a great

arc from eastern and northern Iraq westwards across northern Syria and then southwards toward

the southern Levant (Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Jordan) is often called the Fertile Crescent

(Figure 1.2). Although not part of the traditional Fertile Crescent, the Anatolian plateau of cen-

tral and eastern Turkey shares the same features and thus merits its place on our map. Despite

dry summers, precipitation (rain and, in places, snow) during the cooler months of the year is

sufficient to sustain agriculture. This region had rich natural resources; most important for early

people were gazelle, acorns, and wild grasses. Also among the species present, but not necessarily

so significant for food foragers, were the ancestors of plants and animals that would be domes-

ticated during the Neolithic period. Wheat, barley, and other grains grew wild, and wild sheep,

goats, cattle, and pigs roamed freely.

In this region, with food sources close at hand, early men and women could sustain them-

selves with relative ease. They subsisted by hunting wild animals and gathering edible plants.

They lived in small groups, and moved with the seasons to track animals or collect ripened fruit

and vegetables. Natural shelters, such as caves, often served them as seasonal dwelling places.

These hunters and gatherers crafted tools made from flakes of flint or pieces of bones; their

European contemporaries even painted fantastic scenes of such crucial events as the hunt or

modeled figurines of plump nurturing mothers. This situation lasted through the fourth gla-

ciation. This long period is variously known as the late Pleistocene (the geological term) or the

Upper Paleolithic and the succeeding Mesolithic (the cultural terms).

But these Paleolithic and Mesolithic men and women did not know the art of pottery or met-

alworking, they could not read or write, and they had little control over their food sources. These

skills – agriculture (including cultivation and animal husbandry), pottery making, and metallurgy

– plus recording systems utilizing clay tokens (but not yet actual writing) were developed during

the Neolithic period in the Near East. So important was the transformation that Childe termed

this the “Neolithic Revolution.” The word “revolution” may be misleading, however. Although

indeed drastic, these changes did not take place overnight. They developed over long periods, at

varying rhythms in different regions, often blending or coexisting with earlier modes of subsis-

tence and seasonal movements.

Anyone can spot the existence of pottery or metal objects. In contrast, the search for speci-

mens of domestic vs. wild plants and animals from this period of transition demands special

skills and training. Archaeologists working at such early sites collect animal bones and plant

remains, with the smaller specimens obtained by passing excavated dirt through a fine-meshed

screen. Plant remains can also be collected by means of flotation: a sample of excavated earth is

poured into water; seeds and other plant remains will then float to the surface, from which they

Figure 1.2 The Fertile Crescent in the earlier Pre-Pottery Neolithic, ca. 7500–6500 BC

NEOLITHIC TOWNS AND VILLAGES 17

can easily be removed. Since the forms of the domesticated versions of seeds and bones have

changed distinctly if slightly from their wild ancestors, the specialist can assess how far the pro-

cess of controlling certain plant and animal species had advanced at a particular place and time.

At present, it appears that plant cultivation began in the southern Levant, probably in that

part of the Levantine corridor between Damascus and Jericho. Here, in well-watered areas with

a range of edible wild plants and animals, people had already established settlements (even as

simple as seasonal encampments) during the late ninth to early eighth millennia BC. The onset

of a drier climate, reducing the fertility of wild plants, may have spurred people to cultivate their

own plants as a supplement to dwindling wild supplies. A subsequent return to a wetter climate

ensured the survival and growth of these experiments in farming.

Animal domestication developed later than plant cultivation, and in a broader area of the Near

East, the Levantine corridor plus the highlands of Anatolia and the Zagros (Iran). Settled farmers

kept herds of, first, goats and sheep, beginning in the late eighth millennium BC. Cattle and pigs

would be widely domesticated later, from the later seventh millennium BC.

With the control of food sources developed in the Neolithic Revolution, people no longer

needed to move around in order to take advantage of seasonal and fl uctuating resources, but

could remain in one place. Farmers could sow crops as they wished (subject to local climate and

soil conditions, of course), and maintain herds of animals. Hunting and gathering of wild animals

and plants would continue, but now for the purpose of supplementing the diet. This sort of

agricultural economy was the basis for permanent, year-round settlements. Out of small village

clusters would emerge towns and eventually cities. Just as the existence of sedentary settlements,

however simple, was a prerequisite for plant cultivation, so in turn would the practice of agricul-

ture (plant cultivation and animal husbandry) give rise to concepts of land use and ownership

that would infl uence the nature of the settlements, and subsequent urbanism.

JERICHO

Jericho, in the Jordan River Valley in Palestine, inhabited from ca. 9000 BC to the present day,

offers important evidence for the earliest permanent settlements in the Near East. Explored

during the 1930–36 excavations of British archaeologist John Garstang and more extensively in

1952–58 by his compatriot Kathleen Kenyon, the first settlements at Jericho surprise us still with

a variety of features of town layout unexpected (and still unparalleled) at such an early date.

Two early levels from the mound at Jericho are of particular interest for us: the Pre-Pottery

Neolithic (“PPN”) A and B phases, ca. 8500–6000 BC. They lie on top of the earliest known

settlements at Jericho, seasonal occupations attributed to so-called “Natufian” Mesolithic and

Proto-Neolithic (= earliest Neolithic) hunters and gatherers. A key attraction for all these early

inhabitants was the spring, a reliable source of water.

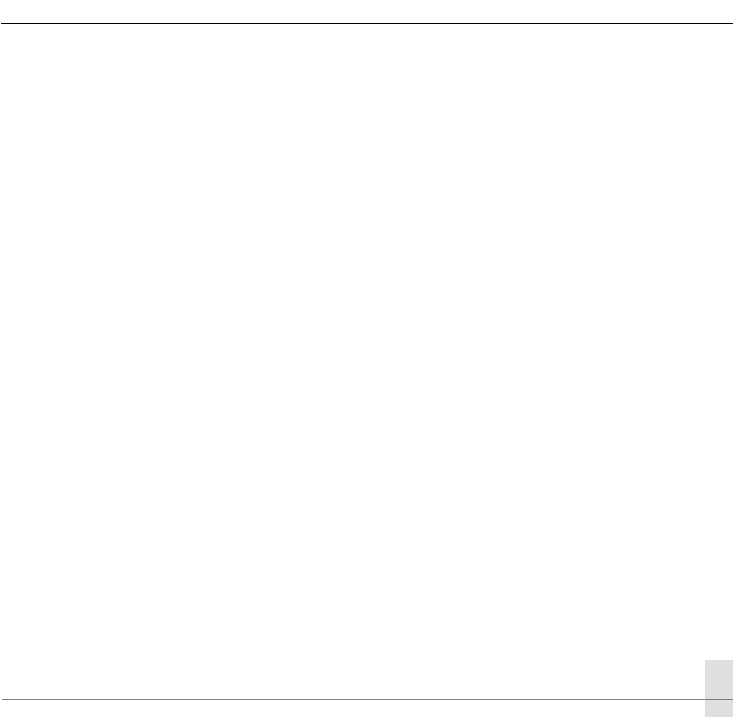

Spread over an area of ca. 4ha, the PPNA settlement has yielded both houses and a fortifica-

tion wall (Figure 1.3). The houses are round, and made of sun-dried mud bricks with a distinctive

rounded top (“hog backed,” or “plano-convex”). The town was protected on the west side, at

least, by an impressive stone wall 3.6m high with an internal circular tower of undressed stones

measuring 9m in diameter at its base and preserved 8m in height, and a rock-cut ditch in front.

Internal stairs led to the top of the tower, perhaps the site of cultic activities. Exactly what the

wall and ditch were protecting the town against has been the subject of controversy; enemies

both human and natural (such as seasonal flash floods) have been proposed. The mere existence

of this complex fortification system implies a society organized in a way quite different from

18 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

that of earlier hunters and gatherers. Conflicts with people outside were serious enough to war-

rant a major fortification wall, and nature need not dominate but could be subdued. The actual

construction of the wall demanded a concerted, sustained effort on the part of the inhabitants. It

was a remarkable architectural and social achievement.

The presence of obsidian objects in the town indicates trade contacts with far-off lands. A

volcanic glass prized as a material for sharp blades in this era before metalworking, obsidian

occurs in only a few scattered and, for the inhabitants of Jericho, distant sources. Finding it here

demonstrates that even at this early period materials could be transported long distances, in this

case from the volcanic mountains of central and eastern Anatolia.

Jericho in the subsequent PPNB phase featured new architectural forms, possible indicators

of social changes. House builders abandoned the round house in favor of the rectangular plan,

with rectangular rooms arranged around a central courtyard. Construction used a different form

of sun-dried mud brick: “cigar-shaped’’ bricks with finger impressions across the top to key in

the mud mortar. House decoration now included walls often painted red or pink, floors plastered

with gypsum, and the occasional reed mat, attested by impressions surviving on the floors.

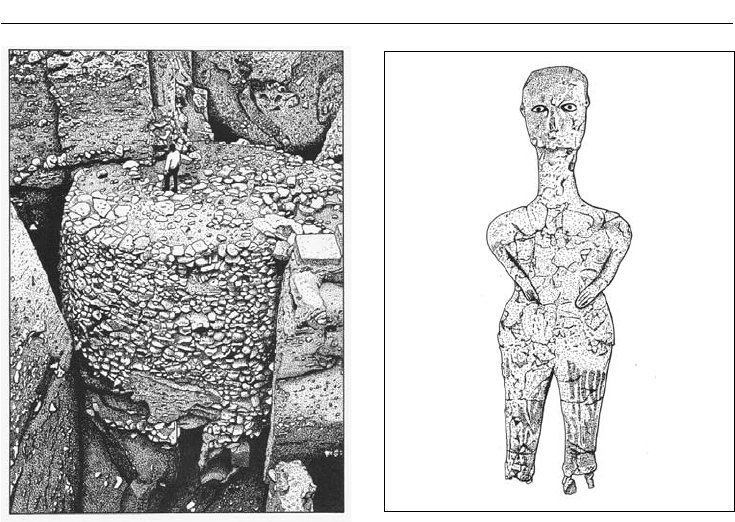

The PPNB has also yielded evidence for religious practices. One particularly large room (6

× 6m) may represent a shrine. A dramatic find from beneath a house floor was a series of ten

human skulls with faces carefully recreated from added plaster and, for the eyes, pieces of shell.

Related are two anthropomorphic figurines made of lime plaster on a wicker core, with painted

decoration and shell for eyes. These two are now supplemented by thirty-two examples found at

Ain Ghazal, near modern Amman; they measure 0.35–1.00m in height, thus monumental in rela-

tion to the smaller images of earlier times (Figure 1.4). These objects must have had some cultic

purpose, the former perhaps relating to the veneration of ancestors, the latter perhaps represent-

ing deities. Ancestor worship has been an important practice in those farming societies in which

Figure 1.3 Tower with staircase, PPNA, Jericho Figure 1.4 Anthropomorphic figurine, PPNB, Ain

Ghazal. Archaeological Museum, Amman

NEOLITHIC TOWNS AND VILLAGES 19

the extended family is the major social grouping, for a long chain of ancestors lends authority to

a family’s claim to its land and helps justify and stabilize the family unit.

In terms of the economy, the PPNB period marked a growing agricultural prosperity. The

success of plant cultivation in PPNA led to the spread of domesticated plants elsewhere in the

Near East during PPNB. In addition, animal husbandry began at this time. Wild game would

have dwindled in the immediate vicinity of settlements, so the domesticated herd animals were

relied on for food. In addition to this primary product, meat, the so-called “secondary products”

of these animals (such as milk, hair, skin, transport, and their use for traction, that is, pulling

plows and vehicles) now became valuable. Consequences of this agricultural prosperity included

agricultural surpluses, an increase in human population, specialization of occupation (not every-

one had to be a farmer), and an increasing complexity in social organization. No wonder, then,

that Bar-Yosef and Meadow have called the PPNB “the brewing period for the emergence of

major civilizations” (1995: 92).

Following the end of the PPNB town at Jericho, a gap in occupation lasted some 1,500 years.

This collapse of the social “proto-urban” system was general throughout the southern Levant,

with a few exceptions in Transjordan. The reasons for this change are not clear. Eventually

Jericho was resettled, but by a pastoralist community smaller than the earlier PPNB town. The

newcomers counted pottery-making among their skills. But Jericho was no longer at the fore-

front of innovation. Already in the seventh millennium BC, at the same time as the PPNB phase

at Jericho, the art of pottery had emerged in Iran, northern Iraq, and Anatolia.

ÇAYÖNÜ

Excavations at Çayönü allow us to trace the development of early towns ca. 8250–5000 BC, from

the PPNA and PPNB phases, as seen at Jericho, to the next stage, the Pottery Neolithic. Particu-

larly striking are the varieties of architectural expression that occur over this long span of time,

and the early appearance of such technologies as metallurgy. Unlike Jericho, Çayönü never had a

fortification wall. What we do see are houses and public buildings of varied plans and materials,

and open spaces, arranged in differing ways. Çayönü gives us a broad range of the possibilities of

town plans in the Neolithic period.

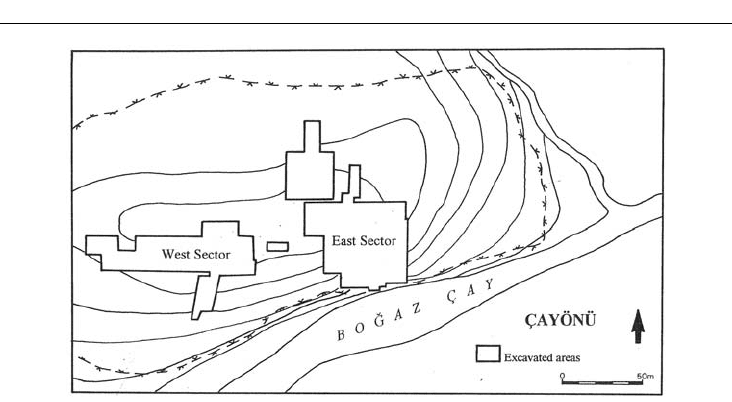

The site of Çayönü is located 60km north of Diyarbakır in south-eastern Turkey, on a tribu-

tary of the Tigris River that flows by the foothills of the Taurus Mountains (Figure 1.5). Exca-

vations were conducted here from 1964 to 1991 by the universities of Istanbul, Chicago (the

Oriental Institute), Karlsruhe, and Rome, under the direction of, first, Halet Çambel and Robert

Braidwood, and, later, Mehmet Özdog˘an. Although Çayönü is far from being the largest of Near

Eastern Neolithic sites, it does boast the largest area of Neolithic settlement as yet exposed by

archaeological excavation: 8,000m

2

.

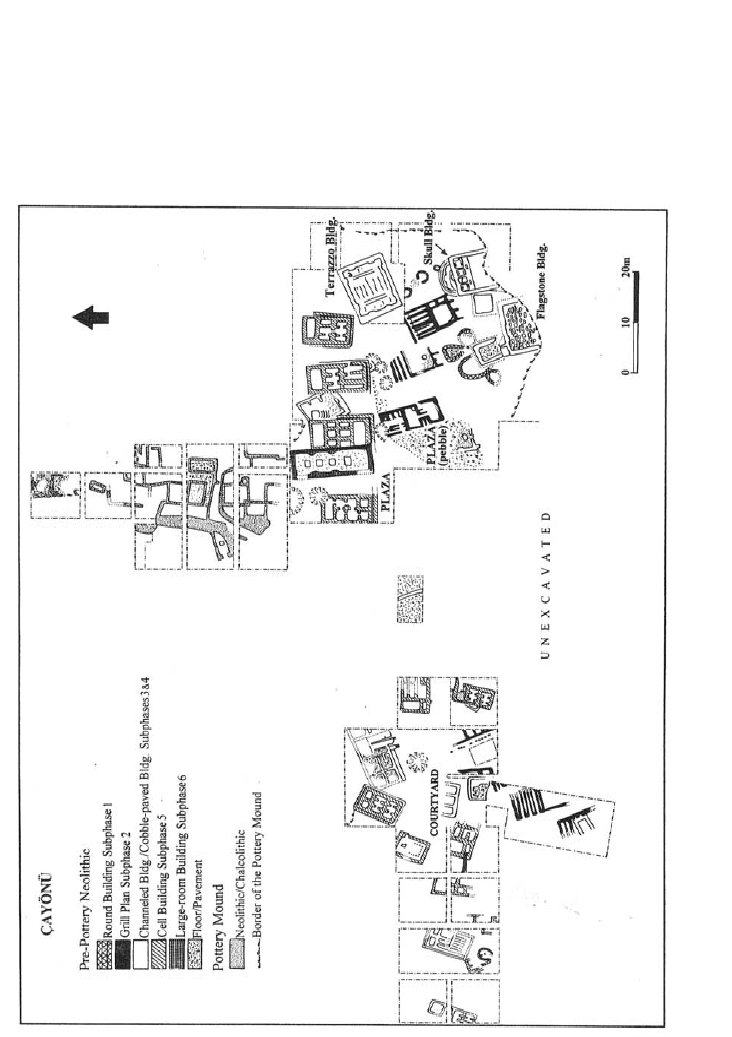

The PPN (PPNA and PPNB together = Phase I) consisted of six subphases, each named after

its characteristic architectural type (Figure 1.6). Subphases 2, 5, and 6 are the most striking. In

Subphase 1, the Round Building subphase, the village contained round or oval houses made of

wattle-and-daub, a rough lattice of twigs and branches covered with a mix of mud, straw or grass,

and perhaps dung. Floors were sunk below ground level. Subphase 2, the Grill Plan subphase,

featured rectangular houses with foundations of parallel stone walls, a pattern that resembles a

grill. Flooring, laid on top of these foundations, consisted of twigs and branches covered with

lime and clay. The superstructure continued to be made of wattle-and-daub. In plan, houses had

three parts, a living area (on the foundations described above), an enclosed courtyard, and a small

20 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

storage area. Houses resembled each other in size, plan, and orientation, and were arranged in a

checkerboard pattern. These regular features suggest the existence of a well-defined architectural

code obeyed by all.

In Subphase 3, the Channeled Building subphase, the house foundations were largely filled

in, leaving only drainage channels. The village grew larger in area, but with houses scattered at

greater intervals. A cult area was established on the eastern edge of the settlement, a neatly kept

open space called the “Plaza” by the excavators. In this subphase, two rows of large standing

stones were set onto the clay floor.

Subphase 4, the Cobble-paved Building subphase, saw houses protected from groundwater by

cobble fill instead of drainage channels. The Plaza continued as before.

In Subphase 5, the Cell Building subphase, houses were much larger than before. As in all the

subphases, earlier buildings were deliberately abandoned and filled in, with the new type erected on

top as a concerted renewal project. The division of the stone foundations into cell-like compart-

ments, perhaps used as storage rooms, characterizes the architecture. The superstructures were

made of mud brick, not wattle-and-daub. House plans and sizes varied, sometimes including large

courtyards. The Plaza was now encircled by the largest houses of the settlement, a testimony to

the importance of the space. Furthermore, the finds within the houses varied. Such differences of

house plans and contents, contrasting with the uniformity of Subphase 2, suggest social distinctions

in operation: Childe’s second criterion of the city, “developed social stratification.”

Subphases 1–5 featured four striking communal buildings. The later three have been identified

as cult centers, because of their distinctive architectural features and contents. Their exact place-

ment in the architectural subphases is not certain, because they were erected on their own terraces

cut into the edge of the site and co-existed through various rebuildings. Nonetheless, the order of

construction seems to be as follows. The earliest was a large round structure. The next, the large

“Flagstone Building,” contained a floor of polished limestone slabs 2m long; large stones were set

upright on the floor. The third is the “Skull Building,” rebuilt at least six times, but always contain-

ing human skeletons or fragments. Seventy human skulls were found when the building was first

excavated; the bones represent the remains of over 450 individuals. This building must have been

a charnel house for secondary burials. Perhaps it served as well as a focus for the commemoration

of the dead, a variant of the ancestor worship postulated for Jericho.

Figure 1.5 Overall site plan, Çayönü

Figure 1.6 Plans, Neolithic and Chalcolithic levels, Çayönü