Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 3

Mesopotamian cities in the late

third and second millennia BC

In this chapter our examination of Mesopotamian cities reaches into the late third and second

millennia BC. This is a period of important political change, when the traditional Sumerian con-

cept of the city-state is challenged by state builders, even empire builders, resulting in the larger,

more comprehensive political units of the Akkadians and the Third Dynasty of Ur. With these

political changes come new emphases in architecture and royal imagery, always important ele-

ments of the ideology of cities and their rulers. Most attention will be given to the Sumerian city

of Ur, already introduced in Chapter 2, and to Mari, famous for its monumental palace, a city

created by one of the non-Sumerian Semitic peoples of central and northern Mesopotamia who

would dominate the region for many centuries to come.

THE AKKADIANS

The first era of independent Sumerian city-states in southern Mesopotamia was shattered

by Sargon, King of Akkad (reigned ca. 2370–2315 BC), who conquered the entire region

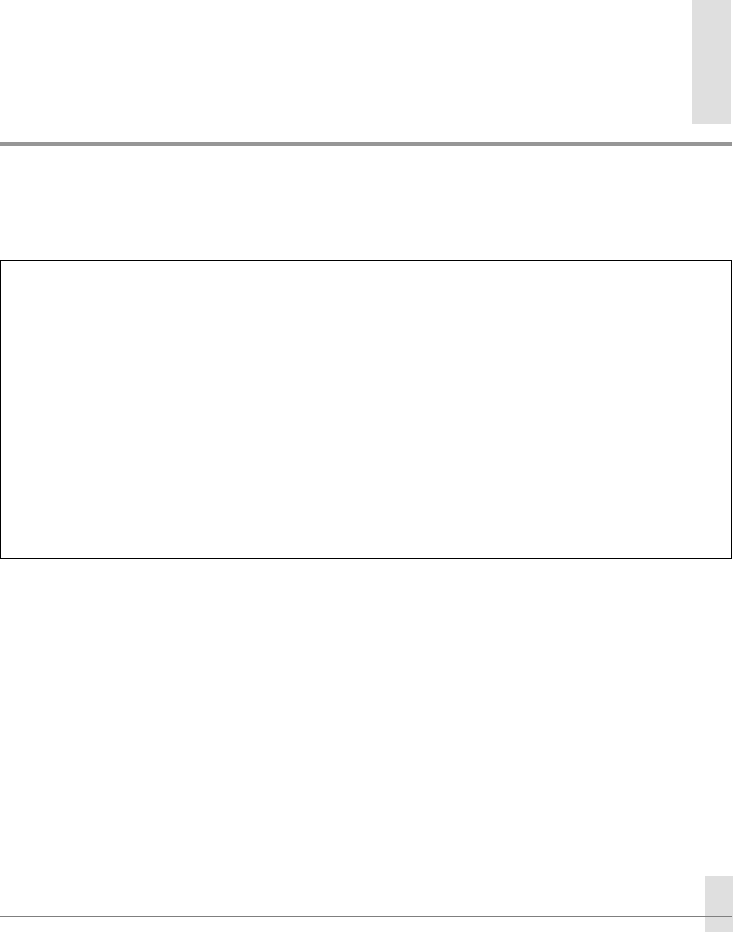

ca. 2350 BC. This great king’s likeness may survive in a life-size (30cm high) cast copper

head found out of context in a much later Neo-Assyrian temple at Nineveh in northern Iraq

(Figure 3.1). With the elaborately braided hair tied in the back, the curled beard, and the

placid smile, this head is elegant and serene. Only the damaged eyes and ears, perhaps

intentional mutilations by the ruler’s enemies to destroy the spirit present in the statue, mar its

tranquility.

The Akkadians: ca. 2350–2150 BC

The Gutians: ca. 2150–2000

BC

The Sumerians (second period of domination):

Neo-Sumerian period: ca. 2125–2000

BC

Gudea of Lagash

Ur III period (= Third Dynasty of Ur): ca. 2100–2000

BC

Old Babylonian period: ca. 2000–1530 BC

Isin-Larsa period: ca. 2000–1760 BC

First Dynasty of Babylon: ca. 1830–1531 BC

Hammurabi of Babylon: ca. 1728–1686 BC

The Kassites: ca. 1530–1150 BC

MESOPOTAMIAN CITIES 53

The Akkadian state is generally considered the first

empire in south-west Asia. The heart of Sargon’s king-

dom was central Mesopotamia, in the region of Babylon

and modern Baghdad. He established a new capital city,

Agade (Akkad), thus breaking with traditional Sumerian

seats of power. To the chagrin of archaeologists, Agade

has not yet been identified, and so we have no Akkadian

city to describe.

Sargon’s activities, however, and those of his succes-

sors are amply reported in the cuneiform tablets. Once

he had conquered the Sumerian cities, Sargon turned

his attention to the east, to Elam (south-west Iran), and

then northwards up the Tigris and westwards up the

Euphrates into central Anatolia. If the ancient accounts

are to be believed, he ventured even as far as the south-

ern edge of the Arabian peninsula and into the Medi-

terranean to Cyprus and Crete. Only parts of this vast

area could be firmly maintained under his authority. But

these campaigns must have had the effect of stimulat-

ing commercial contacts between Akkad and distant

suppliers of timber, metals, and other raw materials.

Sargon was a Semite, not a Sumerian. The language he

spoke, Akkadian, written in a modified cuneiform script

based on the Sumerian, would remain the lingua franca

of the Near East for some 2,000 years until gradually it

ceded its place to Aramaic. The evidence of names of

people and places in the Sumerian tablets indicates that a substantial contingent of Semites lived

in ED Sumer. The further north one went within Mesopotamia, the greater their numbers. Their

origins are uncertain, as is true for the Sumerians themselves. Despite different speech, these

peoples shared the same cultural patterns, the same religious beliefs. For example, Enheduanna, a

daughter of Sargon, became a priestess of Nanna, the moon god of Sumerian Ur. The Akkadian

rulers, however, contributed a new concept of kingship to ancient Mesopotamia, the elevation of

the mortal rulers to the position of ultimate authority in the state, in place of the gods.

The Stele of Naram-Sin

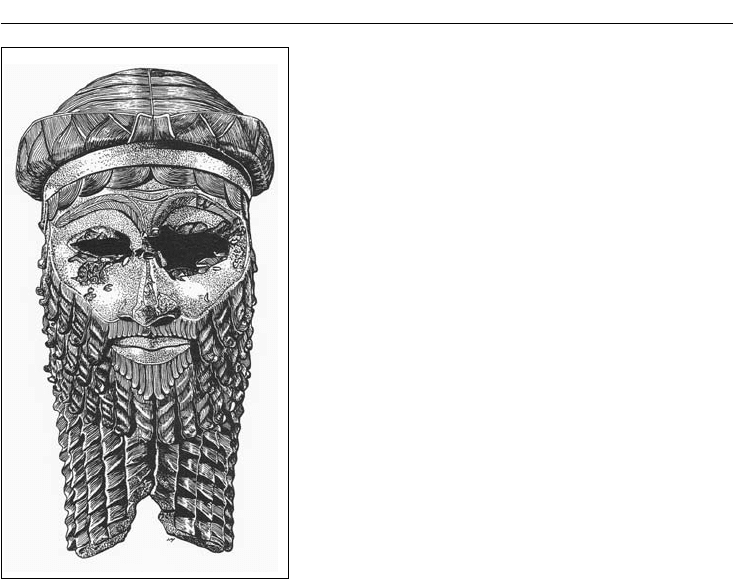

The Stele of Naram-Sin is a parabolic-shape slab of pink sandstone, almost 2m tall, decorated

on one side with relief sculpture that commemorates an Akkadian victory over the Lullubi, a

mountain people living in what is today western Iran (Figure 3.2). The victorious king, here cel-

ebrated by his dominant place in the relief, is Naram-Sin, the grandson of Sargon. During a later,

twelfth-century

BC Elamite invasion of Mesopotamia, the stele was seized as booty and taken to

Susa, the Elamite capital – where the French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan uncovered it in

the late nineteenth century.

The martial theme is already familiar from earlier Near Eastern art, but the composition of

the scene differs from Sumerian examples. Naram-Sin stands high on a steep forested hillside.

He wears a horned helmet, the symbol of divinity, and carries a bow. A representative col-

lection of defeated enemies lies wounded or dead at his feet. In the middle of the stele one

Figure 3.1 Bronze head, Akkadian

period, from Nineveh. Iraq Museum,

Baghdad

54 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

victim plunges head first into the ravine. Below

the king, his own soldiers stride up the hill, or

turn to gaze upwards (those on the right side

of the scene). The sun and the moon (the two

rosette disks in the sky), divinities here, look

down on Naram-Sin and on what may be a

conical mountain – or perhaps a parabola-

shaped commemorative stele.

The relief serves the same propaganda pur-

pose as, for example, the earlier Stele of the

Vultures: the exaltation of the king and his

great victory. On the Stele of the Vultures

(Figure 2.11), the identity of the king Ean-

natum among the warriors is never in doubt,

for he is shown larger than life. But the god

Ningirsu, larger still, very much takes part in

the battle; victory is in fact won because of the

favorable intervention of the god. The Stele

of Naram-Sin builds on this ideological and

visual foundation, but the pictorial expres-

sion of the ruler and indeed the very concept

of kingship have moved in a new direction.

No longer confined to the narrow horizon-

tal bands of Sumerian art, the Akkadian ruler

is displayed in a single grand image. Assisted

by the diagonal lines of the hillside and the

soldiers’ faces turned upwards, the eye of the

viewer focuses immediately on the king. Not

only is he much larger than the other men,

he is also virtually the sole figure in the entire

upper half of the scene. Most important, as

his horned helmet signifies, he has himself become a god. In confirmation of the image, texts tell

us that Naram-Sin was addressed as a god during his lifetime, the first Mesopotamian ruler to be

accorded this distinction. In this way, the king could claim a share of the prestige and possessions

attributed to the deities.

Assertions of might and divinity did not suffice to protect Naram-Sin and his son Shar-kali-

sharri. The Akkadian dynasty established by Sargon, now over-extended and weakened, was

brought to an end by the Gutians, another mountain people from western Iran, neighbors of

the Lullubi. A Sumerian poet writing several centuries later attributed the disaster to an act of

sacrilege committed by Naram-Sin. According to this poet, Naram-Sin sacked the holy city of

Nippur and defiled the Ekur, the sanctuary to the god Enlil. In revenge, Enlil sent the Gutians

on a rampage. To spare the other cities of Sumer, eight major gods agreed that Agade must suffer

the same fate she inflicted on Nippur:

City, you who dared assault the Ekur, who [defied] Enlil,

May your groves be heaped up like dust . . .

May your canalboat towpaths grow nothing but weeds,

Figure 3.2 Stele of Naram-Sin, from Susa. Louvre

Museum, Paris

MESOPOTAMIAN CITIES 55

Moreover, on your canalboat towpaths and landings,

May no human being walk because of the wild goats, vermin (?), snakes, and mountain

scorpions,

Agade, instead of your sweet-flowing water, may bitter water flow.

(from “The Curse of Agade: the Ekur Avenged,” in Kramer 1963: 65)

And indeed, that seems to be exactly what happened to this proud city.

THE NEO-SUMERIAN REVIVAL: HISTORICAL SUMMARY

The Gutians, the conquerors of the Akkadians, controlled Mesopotamia for less than a century,

leaving few traces in the material record. Gradually the Sumerian cities reasserted themselves,

first, Lagash, notably under the reign of Gudea, and later Uruk, leader of a wide-spread revolt

against the Gutians ca. 2120 BC. Gutian domination was finally ended by Ur-Nammu, king of

Ur. For the next century, Ur-Nammu and his four successors ruled over a united central and

southern Mesopotamia. This great period in the history of Ur is known as the Ur III period, or

the Third Dynasty of Ur. Although Sumerian was restored as the official administrative language,

in other respects the Ur III kingdom took its inspiration from the state of Akkad. Administra-

tion was centralized, from taxation and weights and measures to religious and military matters.

Moreover, Shulgi, the second of the Ur III kings, followed the precedent set by Naram-Sin and

declared himself a god.

GUDEA OF LAGASH

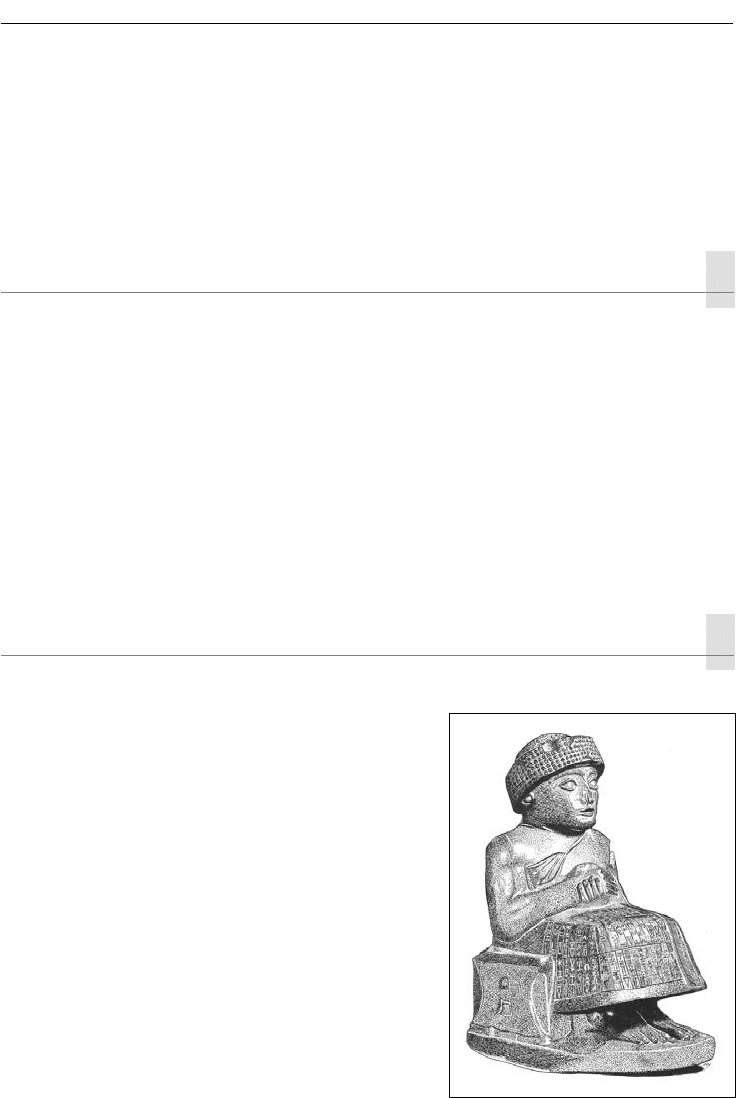

Gudea, a Neo-Sumerian king of the city-state of Lagash, occupies a special position in Mesopo-

tamian archaeology. Tablets discovered during the early

French excavations at Telloh (ancient Girsu) document

his reign exceptionally well. In addition, his image and

that of his son, Ur-Ningirsu, have survived in a strik-

ing series of diorite statues (Figure 3.3). The image of

kingship they present differs markedly from that seen in

the Stele of Naram-Sin. For Gudea, a king best serves

his city not as a warrior, but as a devoted servant of the

gods.

At most half life-size, the statues reflect the predilec-

tion for small-scale figures already seen in the ED figu-

rines of worshippers from Tell Asmar (Figure 2.14). It

is fortunate that inscriptions on the statues themselves

identify the figures as the king, because the features of

face and dress alone do not indicate this. Not true por-

traits, these are standardized, idealized representations

of a king in the position of worshipper. Although occa-

sionally bare-headed and bald, Gudea usually wears a

characteristic headdress, a cap with a broad woven brim.

Whether sitting or standing, he always clasps his hands

Figure 3.3 Gudea, seated statue made

of diorite, from Telloh (Girsu). Louvre

Museum, Paris

56 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

reverently in front of his chest. In one unusual example, a drawing board with the plan of a

temple rests on his knees. The god Ningirsu ordered Gudea, in a dream, to rebuild his temple; the

pious king duly carried out the order, and had the statue made, with an explanatory text carved

on it, to commemorate the deed.

The statues would have been given as gifts to temples. Unfortunately, the exact architectural

context is unknown. While retrieving figures of hard black stone presented no difficulties to the

explorers of Telloh in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, recovering the remains of mud

brick temple walls from a matrix of dirt lay beyond their interest and capabilities.

UR IN THE UR III AND ISIN-LARSA PERIODS

The city of Ur reached its apogee in the late third and early second millennia BC, first as the seat of

the kingdom of Ur-Nammu and his successors. After the demise of the Ur III kingdom, follow-

ing an invasion of Elamites, the city rebounded during the succeeding Isin-Larsa period, enjoying

economic prosperity and continuing as a prestigious religious center. In Chapter 2, we looked

at the Royal Tombs from ED III. More extensive information about the appearance of the city

comes from the later Ur III, Isin-Larsa, and Neo-Babylonian periods and will be examined here:

the fortification walls, the religious center, and the residential neighborhoods (for the city plan,

see Figure 2.15).

At its greatest extent during the Isin-Larsa period, the city measured ca. 60ha, with additional

settlement outside its walls. Population of the city proper may have been approximately 12,000,

using one standard benchmark of 200 persons per hectare, calculated according to an estimated

number of houses per hectare, and of persons per house. But it should be kept in mind that

ancient populations are extremely difficult to determine, and the figures proposed by modern

specialists can vary significantly.

The extant city walls were built in the sixth century BC by Neo-Babylonian monarchs. The

dating of the walls and indeed other construction is much helped by the ancient use of bricks

stamped with the insignia of rulers. Because he did not find in the walls any bricks stamped

with the name of Ur-Nammu, Woolley assumed that the Ur III fortifications were deliber-

ately dismantled by the Elamite conquerors. However, the impressive Neo-Babylonian walls

may well have resembled the Ur III fortifications in both location and appearance. Situated

on a promontory between an arm of the Euphrates and a navigable canal, the city could be

approached by land only from the south. Despite the protection of water on three sides, an

imposing wall 27m thick was built all around. The lower part consisted of a steeply sloping

mud brick rampart, or glacis. This section enclosed and capped the edge of the already existing

mound. On this stood the upper section of baked brick, the wall proper. Defended by water

and such massive walls, the city must have seemed impregnable. But as history has witnessed

time and time again, fortifications and the weapons of war are only as strong as the men and

women who use them.

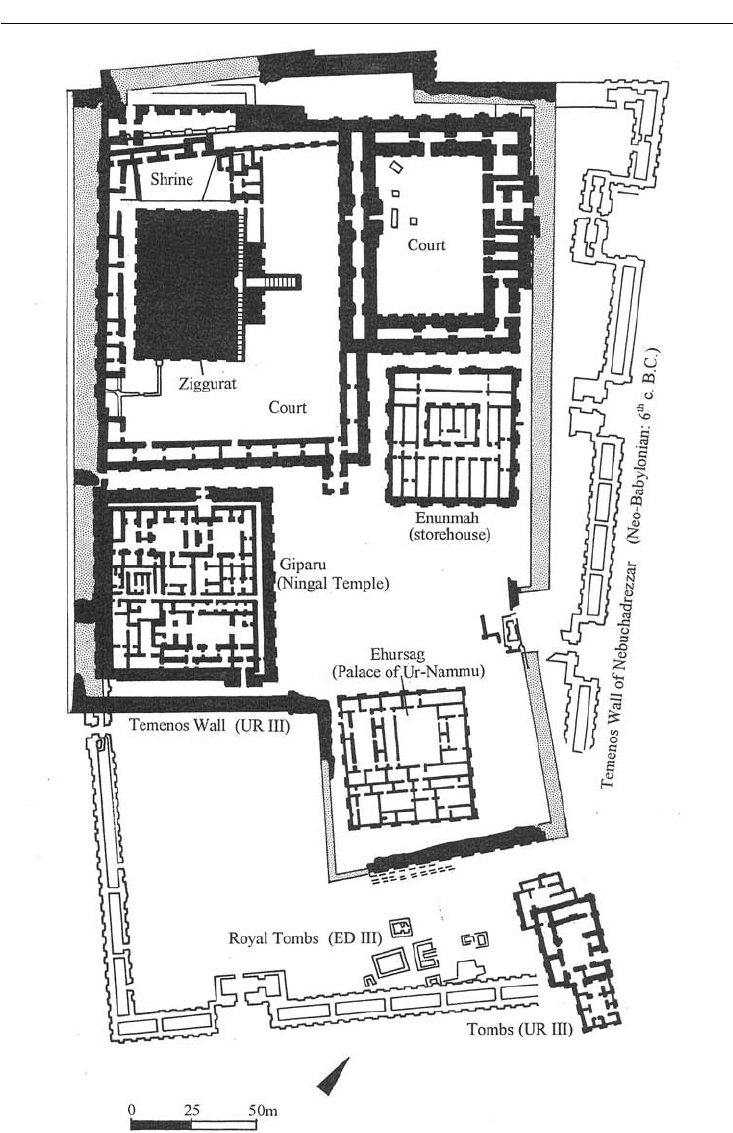

The religious center of Ur

The religious center, devoted to the cult of Nanna, the moon god and patron deity of Ur, and his

wife, Ningal, was a focus of Woolley’s excavations; as a result, much is known about it (Figure

3.4). This temenos, or sacred area, lay in the north-west, the traditional site of the important build-

ings of a Sumerian city. The propitious north-west sector had the healthiest air, it was believed.

MESOPOTAMIAN CITIES 57

Figure 3.4 Plan, the religious center, Ur

58 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Such an attitude may lie behind the frequent orientation of buildings throughout the site toward

the cardinal points: one side would normally face the north-west and its soothing breezes.

Its corners oriented toward the cardinal points of the compass, the entire temenos measured

some 400m × 200m. Buildings were preserved in foundations only, the upper parts having been

destroyed during the Elamite invasion at the end of the Ur III period. The precinct contained

temples, courtyards, and rooms to house the religious personnel and store offerings and cult para-

phernalia, and an enormous ziggurat (see below). In ground plan, the area looks quite forbidding,

with its many thick and reduplicated walls protecting courts and labyrinthine buildings such as the

Giparu, a complex of shrines dedicated principally to Ningal and a residence for high priestesses.

Closely linked to the sacred compound and probably in greater need of the security provided

by the walls was the royal center. The king held audience in the small rooms of the gateway into

the compound for the ziggurat. His palace, the Ehursag, stood close by, just to the east, and

immediately beyond that lay the Royal Cemetery. The tombs of the kings of the Third Dynasty

were not as well hidden as the earlier ED Royal Tombs. Looted in antiquity, only their archi-

tecture has survived, mortuary chapels at ground level with stairs down to vaulted tombs below

– construction on a scale much grander than in the ED tombs.

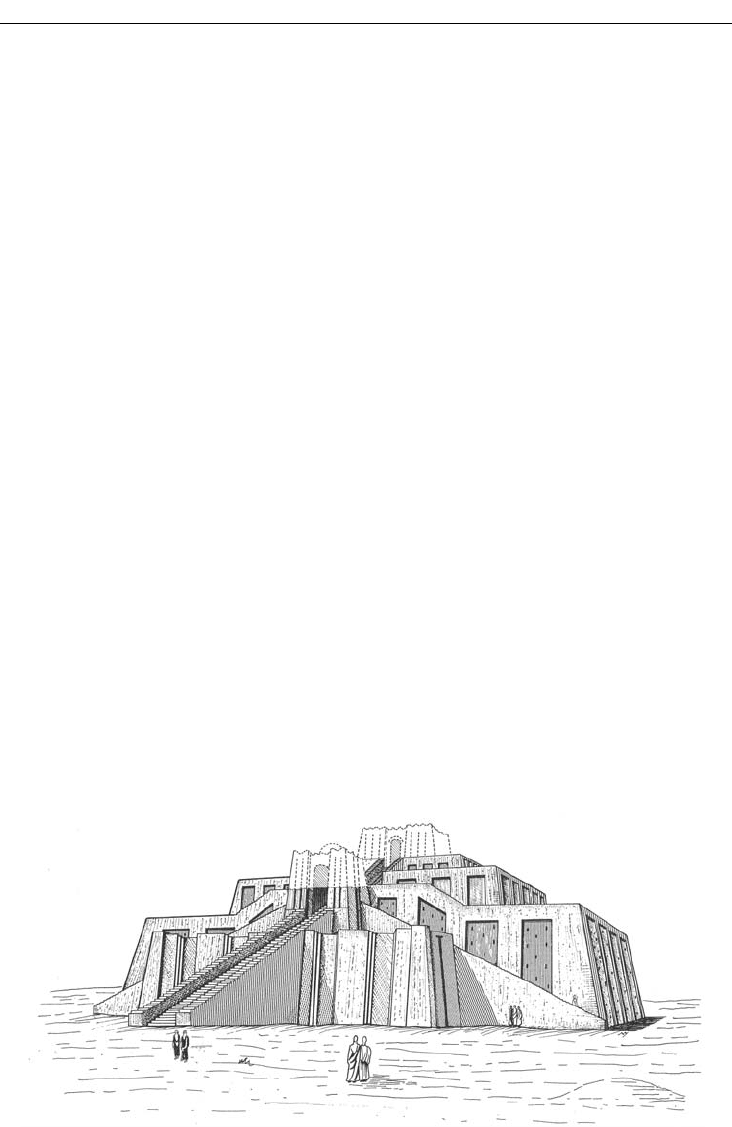

The best-known building of the temenos is the ziggurat, the best-preserved example in Meso-

potamia (Figure 3.5). Erected under Ur-Nammu and his son Shulgi, the ziggurat was restored by

successive generations of kings in Mesopotamia for 1500 years after its initial construction, and

again in modern times by the Iraqi government.

A ziggurat is a tower built of successively smaller platforms one on top of the other, with

a small shrine on the summit. The name may come from Akkadian words for “summit” or

“mountain top” (ziqquratu) and “to be high” (ziqaru). It serves as an artificial mountain in flat

land, reaching up to heaven and the gods, an elaboration of the tall platform which had held up

the Mesopotamian “high temple” ever since the fifth millennium BC.

The ziggurat at Ur consists of three platforms. The temple on top did not survive, so its appear-

ance is conjectural. The lowest platform measures 61m × 45.7m × 15m. A majestic triple staircase

leads up to it and then on to the upper two stages and the shrine on top. Sun-dried mud bricks and

periodic layers of woven reeds make up the solid core of the structure. The exterior was faced with

a thick (2.4m) layer of more durable baked bricks, set in bitumen. Drainage holes pierced the facade

of the lowest platform, a detail that has intrigued observers. Noting finds of carbonized tree-trunks,

Figure 3.5 Ziggurat of Ur-Nammu (reconstruction), Ur

MESOPOTAMIAN CITIES 59

Woolley proposed that the tops of the terraces

were planted with trees. The holes would have

helped drain the specially watered garden. This

appealing vision of the ziggurat as a forested

mountain peak has not been confirmed else-

where.

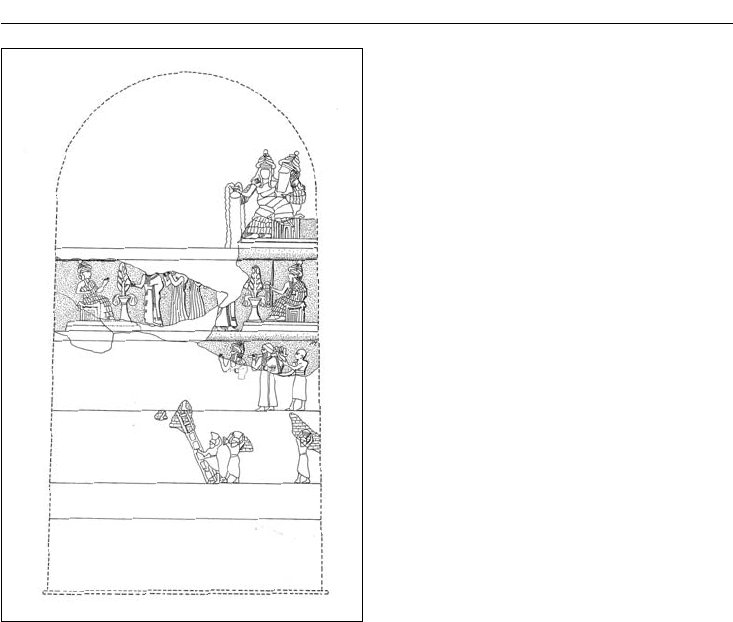

The Stele of Ur-Nammu

The building projects of Ur-Nammu in the

temenos at Ur are honored in relief sculpture

on the Stele of Ur-Nammu, a fragmentary

stele discovered during Woolley’s excava-

tions (Figure 3.6). As did other Mesopota-

mian rulers, Ur-Nammu wished to record

his piety in sculptural form. Like the art of

Gudea, the Stele stresses the king’s adora-

tion of the gods rather than his considerable

military achievements. Not only does its mes-

sage about kingship contrast with that of the

Stele of Naram-Sin (Figure 3.2), the composi-

tion of the relief also differs from the earlier

work, divided as it is into horizontal bands

in traditional Sumerian fashion. In the best-

preserved register, the king appears twice, in

audience with two different divinities, a god-

dess (left) and a god (right). In each scene, the

deity, seated on a platform, watches as the king pours a libation into a plant or small tree growing

in a tall conical pot. Behind the king stands a woman, her hands upraised; also a goddess, she

has the responsibility of presenting the king to the seated gods. Lower, damaged zones depict a

good work of the king, the construction of a temple. Ur-Nammu carries builder’s tools, assisted

by a clean-shaven priest. Nanna, wearing the horned hat reserved for gods, accompanies them in

procession to the building site.

Private houses

Woolley excavated several residential neighborhoods within the city. The best examples, found

south-east of the temenos, date to the Isin-Larsa period, in the twentieth century BC. The plan

with its curving streets and massing of houses contrasts with the regular layout of Protoliter-

ate Habuba Kabira of some 1,200 years before. There was no attempt to place straight, wide

streets at regular intervals. The paths granting access to pedestrians and pack animals never

received much consideration from home owners or municipal authorities, and their courses

must have weaved back and forth as the buildings that lined them were demolished and rebuilt.

Further, trash would be randomly discarded into the streets. In the ancient city, as indeed in the

Middle East today, the interior of the home, one’s private space, was the focus of respect and

attention, not the public streets outside. Even so, the need for some regulation of public streets was

recognized, as this omen text indicates:

Figure 3.6 Stele of Ur-Nammu, Ur. University

of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and

Anthropology, Philadelphia

60 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

If a house blocks the main street in its building, the owner of the house will die; if a house

overshadows (overhangs) or obstructs the side of the main street, the heart of the dweller in

that house will not be glad.

(Frankfort 1950: 111)

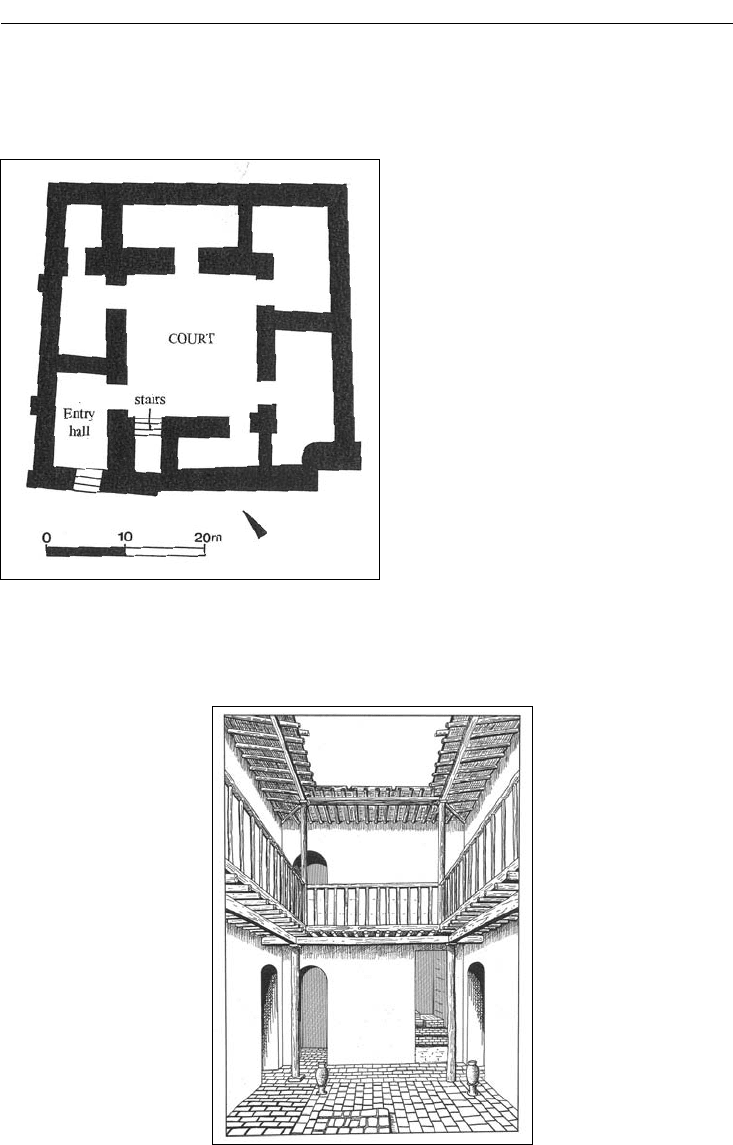

The grandest houses at Ur surpass their

counterparts at Habuba Kabira. They con-

sist of two stories of rooms arranged around

an open air court (Figures 3.7 and 3.8). This

design differs from house plans at Habuba

Kabira, in which a single story and set of

rooms lay at the rear of a court. As typical

in all periods, the walls as seen from the

street are completely unadorned. What lies

inside belongs strictly to the family and their

friends. In addition, the dead were often bur-

ied in the house beneath the ground floor, a

practice reminiscent of Neolithic Çatalhöyük.

But burial practices could vary. Cities would

often have separate areas for cemeteries.

Simpler house plans also exist. These

evidently belonged to shops, distributed

throughout the residential quarters with

heavier concentrations in the southern part

of the city. In addition to houses and shops,

the city plan also contained small shrines,

located at street crossings.

Figure 3.7 House plan, Isin-Larsa period, Ur

Figure 3.8 House interior (reconstruction), Ur

MESOPOTAMIAN CITIES 61

HAMMURABI OF BABYLON AND THE OLD

BABYLONIAN PERIOD

The second period of Sumerian domination in southern Mesopotamia came to an end with the rise

to power of Hammurabi, king of Babylon, in the late eighteenth century BC. Indeed, Babylon, one

of the great cities of the Ancient Near East, first emerged as a major political center at this time.

Hammurabi’s achievements were considerable. Not only did he bring north and south Mesopota-

mia under his control, duplicating the accomplishment of Sargon of Akkad, but he also revamped

the administrative system of the country. Noted particularly for codifying the traditional laws of

Mesopotamia, he had his legal reforms inscribed on a near-cylindrical basalt stele 2.1m high, the

so-called Stele of Hammurabi (Figure 3.9). On the top of the stele is a single scene, a relief sculp-

ture that shows Hammurabi in audience with the seated god Shamash, god of justice. The encoun-

ter of king with god resembles that shown on the Stele of Ur-Nammu. The imagery on the latter

stele stresses the deference of the king to the deities, however, as Ur-Nammu pours a ritual libation

before both god and goddess. In contrast, Hammurabi seems to be consulting directly with the

god, without other deities present. It is almost, but not quite, a relationship of equals.

The era in Mesopotamian history that centers on Hammurabi and the dynasty to which he

belonged is called the Old Babylonian period. With the ascendancy of the Semitic Babylonians,

Sumerian disappeared as a spoken language, replaced by Akkadian. Sumerian did continue as a

written language, however, esteemed as the vehicle of religious and literary values – one reminder

of the enduring strength of Sumerian culture.

MARI: THE PALACE OF ZIMRI-LIM

The key example of an Old Babylonian city is not Hammurabi’s capital at Babylon, where later

constructions of the first millennium BC survive best (see Chapter 10), but Mari, halfway up the

Euphrates in modern Syria close to the Iraqi frontier. The evidence provided by the Palace of

Zimri-Lim, the principal building of eighteenth-century BC Mari, is well complemented by the

important find of over 25,000 clay tablets; together, architecture, art, and texts give us a full

picture of the life of this city. Excavations conducted by French teams since 1933 have barely

touched the town beyond the walls of the palace. Because the palace by itself seems like a town

in miniature, this lack has not drawn much attention until recently.

Already important in the Early Dynastic period, Mari reached its height during the rule of

Zimri-Lim, a regional potentate, ca. 1715–1700 BC. Zimri-Lim and the inhabitants of Mari were

Semites. They wrote in the Akkadian language, but proper names and non-Akkadian words

found in the Mari tablets place them in the north-west Semitic sphere together with such peoples

as the Amorites. Mari grew rich thanks to its advantageous location on the trading routes from

the west and the Mediterranean to both the Assyrian area to the north-east and Babylonia to the

south-east. Taxes were imposed on all goods that passed through. The palace that Zimri-Lim

inherited and remodeled so grandly was destroyed by Hammurabi of Babylon in ca. 1700 BC, but

the substantial remains initially excavated in only five years under the direction of André Parrot

allow a good look both at the architecture and at the workings of society and economy in the

eighteenth century BC.

This palace illustrates an important shift in the government of ancient Mesopotamian cities.

For the early Sumerians, everything belonged ultimately to the gods; human beings merely held

the cities and the land and its fruits in trust for them. During the Protoliterate and Early Dynastic