Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

82 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

the conical white crown of Upper Egypt, his native region, and accompanied by his sandal

bearer, the king grabs an enemy by the hair and prepares to strike him with his mace. The king is

depicted with face and legs in profile, eye and torso frontal. This method of showing the human

body would remain standard through the many centuries of Egyptian civilization even into the

Roman period. To the right of the king, a falcon, representing the sky god Horus, holds by a cord

the curious figure of a man with papyrus leaves sprouting from his body. Horus, the alter ego of

the pharaoh, has captured Lower Egypt, personified here by the papyrus man. In a smaller zone

at the bottom of the palette, humiliatingly placed below the king’s feet, two naked captives are

shown as if floating, stripped of the dignity of clothing and the security of firm ground.

The other side is divided into three zones. In the uppermost, the pharaoh inspects the

beheaded bodies of the defeated. The artist indicates his kingly status by showing him towering

above his attendants. To complement the royal headgear on the other side, the king here wears

the red crown of Lower Egypt, the land he has conquered. In the second zone, two long-necked

monsters are secured by a rope in the hands of an attendant; the monsters may represent larger,

cosmic forces of chaos, now subdued by the king. At the bottom, a bull, another symbol for

the king, tramples a naked enemy. Beyond them lies a walled town, an example of the Lower

Egyptian settlements captured by Narmer and his forces.

The glyphs for the king’s name and the pictographic nature of some images on the palette

remind us that writing began in Egypt in the century or two before Narmer’s unification of

Upper and Lower Egypt. Egyptian writing, in use for over 3,000 years, is one of the fascinating

achievements of this culture.

EGYPTIAN WRITING

The language of the ancient Egyptians belongs to the Hamito-Semitic language family at home in

south-west Asia and north Africa. The idea of writing arose in Egypt at approximately the same

time as it did in Mesopotamia, and marks a certain stage in the development of the state reached

in both regions.

Although we can now understand Egyptian scripts, we do not know how words were pro-

nounced. The Egyptians wrote in three scripts. Hieroglyphs, or “holy carving,” the picture signs,

were used from ca. 3050 BC to 394 AD. It could be written in lines or columns from either left to

right or right to left, with the signs reversible according to the direction in which they were read.

The second script is hieratic, used from Dynasty I well into the Late Period. Written from right

to left only, hieratic was a cursive version of hieroglyphs, adapted in particular for writing with

a reed brush in ink on papyrus (Egyptian paper, made from the fibrous interior of the papyrus

reed) or on ostraka (potsherds or limestone flakes). The third script was demotic, a Late Egyptian

cursive script used especially for secular documents. Eventually, in the late third century AD, the

much evolved Egyptian language was written in an adapted Greek alphabet. The language and

this new script are called Coptic. Spoken into the sixteenth century AD, Coptic is still the liturgical

language of the Christian Coptic church in Egypt.

The hieroglyphic script consists of approximately 700 signs. These signs can be phonograms

(conveying sounds) representing one, two, or three consonants; ideograms (an image of the

object or idea); or determinatives (showing the class to which a word belongs). Words often con-

sisted of a combination of phonograms followed by an ideogram and a determinative. Although

the system may seem awkward, as a monumental script used for visual effect it has had few rivals

in the history of writing.

EGYPT OF THE PYRAMIDS 83

The decipherment of the hieroglyphic script was made possible by the Rosetta Stone, a bilin-

gual inscription discovered in 1799 by French soldiers near the town of Rosetta (Rashid) in

the Nile Delta. The inscription, a decree of the Hellenistic king Ptolemy V Epiphanes issued

in 196 BC, is actually written in three scripts, the first two Egyptian (with different forms of the

Egyptian language) – hieroglyphs (top) and demotic (middle) – and the third Greek (bottom).

Comparison of the Greek with the Egyptian texts allowed rapid advances in the understanding

of the Egyptian scripts. The comprehensive breakthrough, announced in 1822, was made by

Jean-François Champollion. Champollion had mastered Coptic en route, believing (correctly)

that it held a key to the long forgotten ancient language.

BURIALS OF THE ARCHAIC PERIOD

The first two dynasties are often labeled the Early Dynastic or Archaic Period. Although this

period is poorly known, it seems that the main features of Egyptian civilization were established

then: not only the conventions of drawing the human body and hieroglyphic writing but also

the organization of the state, religious and funerary beliefs, and art and architectural forms. Our

assessment of these important developments depends heavily on the monumental tomb com-

plexes that have survived so well. Written documents are short, and the towns, such as Memphis,

the early capital, buried in Nile silt or under modern occupation, are difficult to investigate. Since

the tomb complexes were erected in the desert beyond the zone of cultivation, they have been

much more accessible to archaeologists. Abydos and Saqqara contain the key cemeteries of the

period.

The dry climate of Egypt, because it preserves organic materials – including the human body

– surely influenced Egyptian notions of the afterlife. The Egyptians believed that life continued

after death with little change. The body was resurrected, and the deceased led the same sort of

life he did before: the same family members, village, and socio-economic conditions. But this

afterlife did not materialize automatically. Burial procedures and rites had to be performed cor-

rectly and, at least from the Fifth Dynasty on, Osiris, the god of the underworld, had to give

his approval. The wrapping of the body, the selection of objects placed in the grave, and the

decoration of the tomb were carefully done to ensure that the deceased reached the afterlife and

flourished there. Thieves could disrupt this well-planned journey, however. In consequence, the

long history of tomb design in ancient Egypt was the never-ending search for the perfect protec-

tion for the body and accompanying materials.

Embalmment and mummification

In Predynastic Egypt, a body buried in a simple pit would be well preserved by the hot, desiccat-

ing sand. As tomb structures became more complex, the body was placed in shafts or chambers

well removed from that beneficial sand. Despite advances in tomb design, the body decom-

posed rapidly. Eventually the Egyptians became aware of the consequences, and to counter

them, developed elaborate procedures of mummification, that is, embalmment and wrapping of

the body. The term comes from the Arabic word “mumiya,” meaning bitumen, a tar in which, it

was mistakenly thought, the blackened, poorly embalmed bodies from the late periods had been

dipped.

The earliest known evidence of classic or standard mummification is from the tomb at Giza of

Queen Hetep-heres, the mother of Khufu, the important king of the Fourth Dynasty. Although

84 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

her body was not found, a Canopic chest containing four of her organs proved that the stan-

dard process of embalmment was already being performed. The most skillful mummifications

come from the New Kingdom. Although classic techniques faded in the Hellenistic period, the

practice continued, with different degrees of elaboration (depending on how much one could

afford), into the early Christian period.

The organs were removed (except for the heart, the spiritual sentinel, which remained in the

body in order to testify at the moment of Judgment), since they putrefied first. Four key organs

were given special treatment: the stomach, the intestines, the lungs, and the liver, but not, inter-

estingly, the brain, which was apparently discarded. They were washed, packed and dried in

natron (a naturally occurring salt), painted with resins, wrapped in separate bundles, and packed

in four Canopic jars, and placed in the tomb. Each was protected by a special divinity.

The body was dried in natron. After a certain period, at least forty days, the natron was

removed and the body was prepared for burial by anointing with oils and resins, and packing

with linen stuffing to restore its original shape. Finally it was tightly wrapped with linen strips to

safeguard that shape, with amulets interspersed in the wrapping.

Mastaba tombs at Abydos and Saqqara

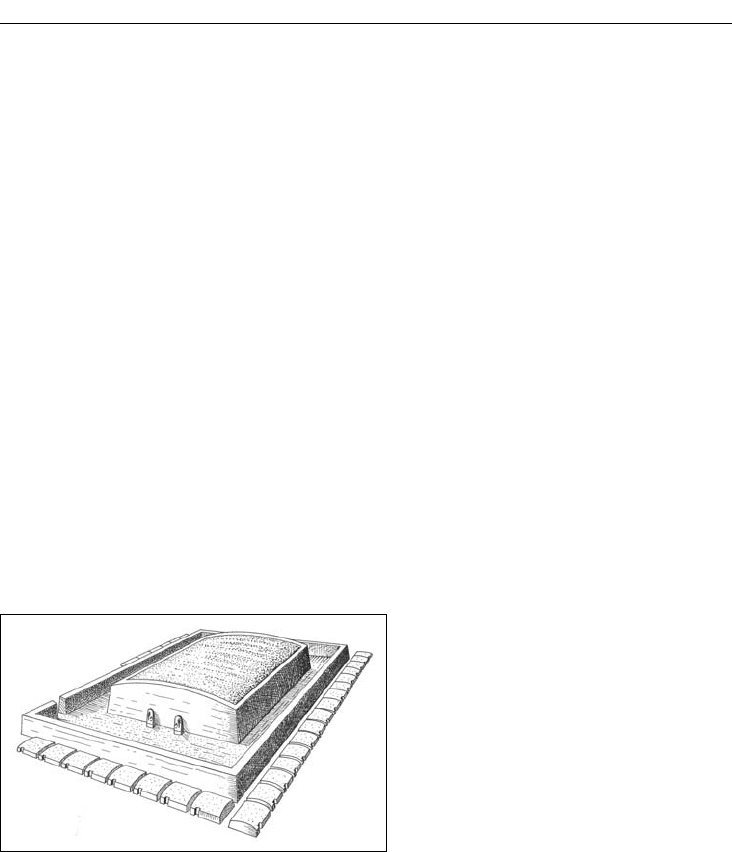

In Predynastic times, burials were simple, with bodies placed in flexed position in shallow pits.

Simple grave gifts might be added, such as a few pots, figurines, tools, cosmetics, and orna-

ments. In the Archaic period, practices became more elaborate. The body was wrapped in linen

and placed with grave goods in a pit sunk 3m–4m into the ground. This burial spot and any

adjacent rooms were covered and protected first by a low mound of earth, and then by a mastaba,

a low, flat, rectangular structure made of

mud brick, a series of compartments cov-

ered by a single roof (Figures 5.3 and 5.4).

The façades were decorated to resemble a

house, with the grandest showing the same

sort of indented façades believed to have

been featured on the palace at Memphis,

the capital city. Such indented façades

were standard in the mud brick architec-

ture of Mesopotamia and, together with

the use of cylinder seals and perhaps the

idea of writing, indicate the high level of

Near Eastern contact in this formative

period of Egyptian civilization.

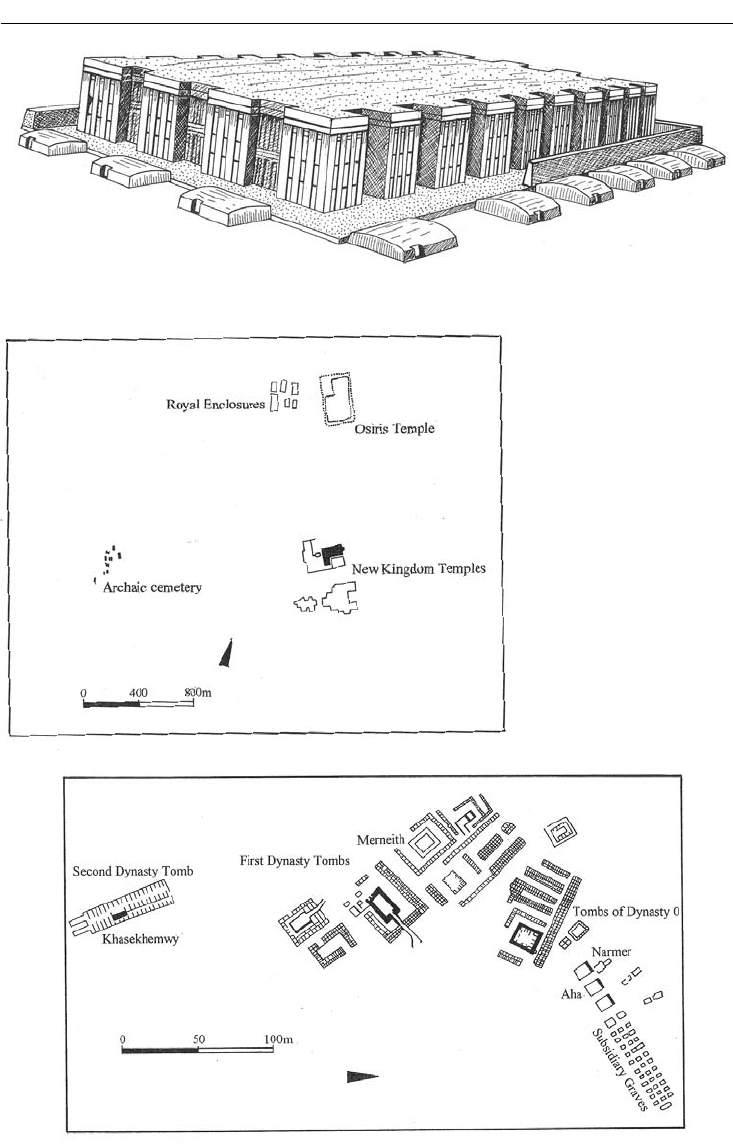

Mastaba tombs beginning with that of King Aha (First Dynasty; Narmer’s successor) at

Abydos were surrounded by simple graves for servants and craftsmen buried with the tools of

their particular trades (Figures 5.5 and 5.6). Thirty-four such tombs accompanied Aha’s burial;

they belonged to seemingly healthy young men, none older than twenty-five, plus a pair of lions.

The men may have been dispatched to accompany their master in the afterlife; their presence

recalls the array of sacrificed servants in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. This practice did not continue

beyond the Archaic period. A good supply of servants was eventually assured by the placing in

tombs of such stand-ins as figures painted or sculpted on tomb walls (beginning in the Fourth

Dynasty); small-scale models of activities from daily life (farming, preparation of food and drink,

etc.), from the First Intermediate Period on; and shabtis (mummiform statuettes), starting in the

Figure 5.3 Mastaba tomb of Queen Merneith

(reconstruction), Abydos

EGYPT OF THE PYRAMIDS 85

Figure 5.4 Mastaba tomb also attributed to Queen Merneith (reconstruction), Saqqara

Figure 5.5 Overall site

plan, Abydos

Figure 5.6 Plan, the Archaic cemetery, Abydos

86 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Middle Kingdom. All these images were given life through the texts written on the walls and

the magic of ritual.

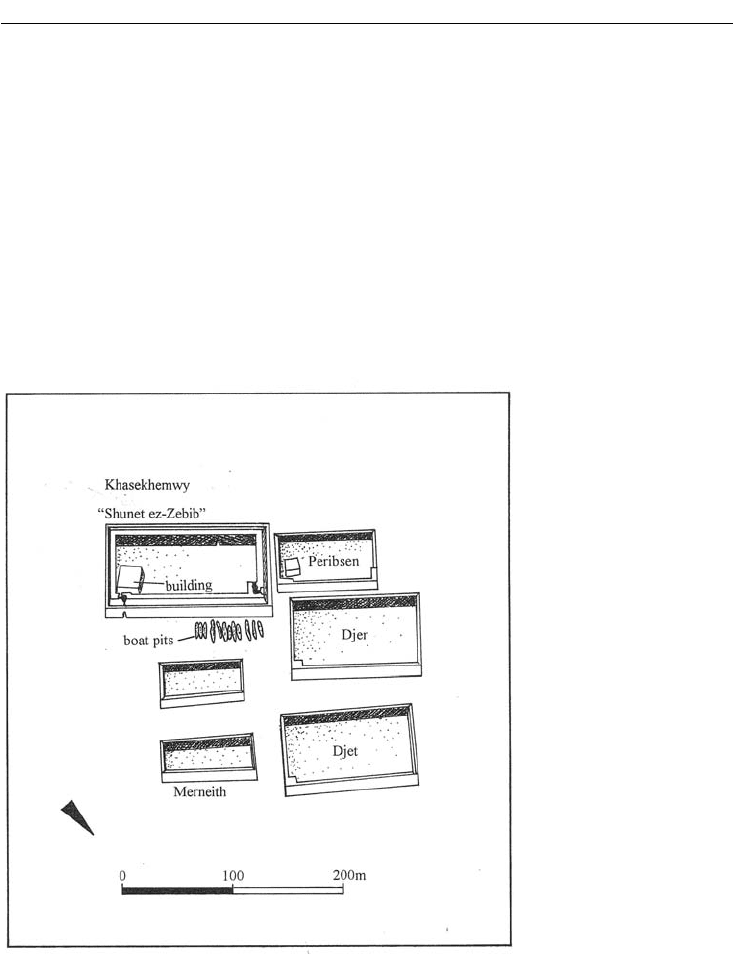

The Archaic cemetery at Abydos contains an important feature seemingly absent at Saqqara:

funerary enclosures. Such enclosures are associated with royal burials. The enclosures may rep-

resent palace courtyards, impressive locations for ceremonial appearances of the kings (Figure

5.7). A few kilometers separate them from the tombs; they lie closer to the cultivation zone,

more accessible for the living. Their walls have indented “palace-facade” decoration, like the

mastabas. Inside they are largely empty space; but the best preserved enclosure, the “Shunet ez-

Zebib,” that of the late Second Dynasty king Khasekhemwy, contained a small building in one

corner. Outside the eastern wall, twelve wooden boats (19m–29m in length) buried in pits may

be connected either with this enclosure or with the adjacent. The presence of the enclosures and

the buried boats in the first two dynasties is significant, for both will reappear dramatically in the

great tombs of the succeeding Third and Fourth Dynasties (see below).

The identity of those buried in the Early Dynastic mastaba tombs at Abydos and Saqqara has

been much argued. Which tombs belonged to the kings? The combination of mastaba tomb

and funerary enclosure makes it probable that Abydos, not Saqqara, was the location for most

First and several Second Dynasty royal burials. Also favoring Abydos is apparent continuity in

burials of distinguished individuals from the later Predynastic period, and the greater number of

subsidiary graves of retainers. In this view the Saqqara mastabas would belong to high officials,

or might represent northern cenotaphs of the rulers buried at Abydos. The question remains

Figure 5.7 Royal funerary

enclosures, Abydos

EGYPT OF THE PYRAMIDS 87

controversial, however, for the mastaba tombs at Saqqara were larger, grander than those at

Abydos, even if without enclosures, and the capital city, Memphis, lay conveniently nearby. In

the Second Dynasty, royal tombs may well have been divided between Abydos and Saqqara.

SAQQARA: THE STEP PYRAMID

The cultural transition from the Archaic period to the Old Kingdom was smooth. The Old

Kingdom consists of Dynasties III–VI, spanning nearly 500 years from ca. 2675 to 2190 BC.

Saqqara, to the west of Memphis, became the prime burial site of the Old Kingdom. Other sites

in the region were also used for cemeteries, but none had the lasting appeal of Saqqara. The

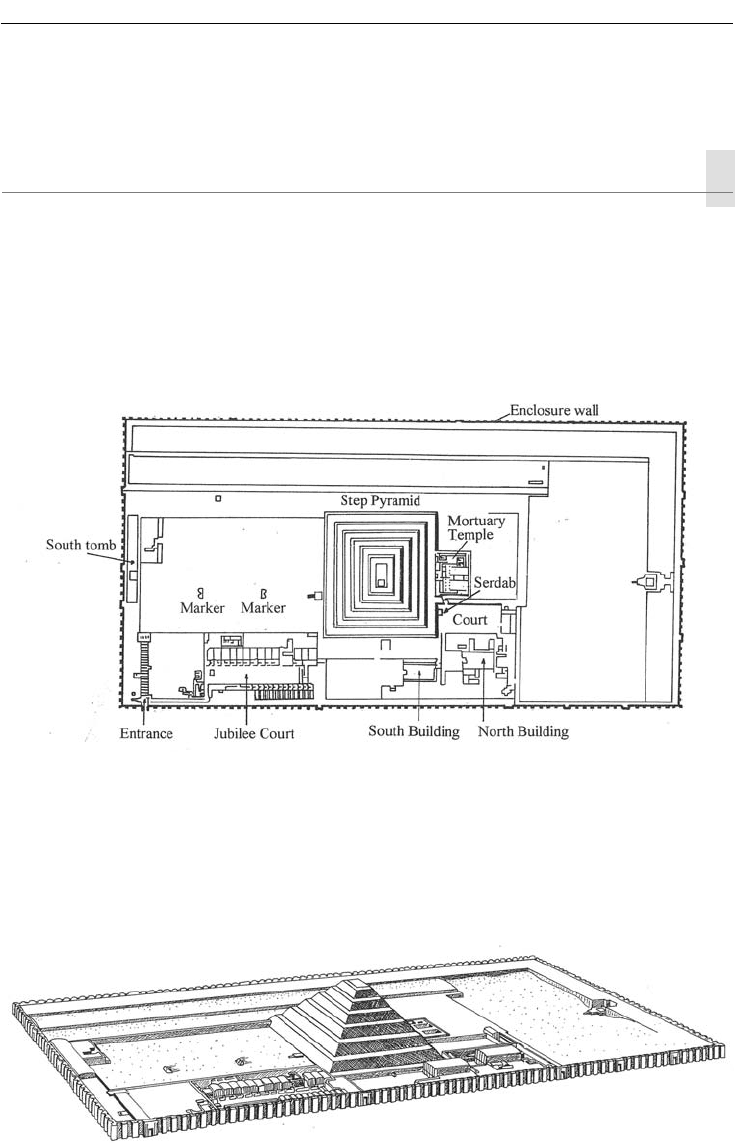

grandest tomb at Saqqara, and one of the key buildings of all Egyptian architecture, is the Step

Pyramid, built for the pharaoh Djoser (or Zoser) of the Third Dynasty, ca. 2650 BC (Figures 5.8

and 5.9).

The Step Pyramid shows bold innovations in both form and building technique. Its form

marks a transition for royal burials from the earlier mastaba tombs to the smooth-sided pyra-

mids of the Fourth Dynasty and later. In construction technique, it is equally important. Instead

of sun-dried mud bricks, stone is the building material. As far as we know, such use of stone

Figure 5.8 Plan, the Step Pyramid and Funerary Complex of Djoser, Saqqara

Figure 5.9 The Step Pyramid and Funerary Complex of Djoser (reconstruction), Saqqara

88 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

has no precedent. Stone was used earlier for details, but never for an entire building. Because

the Egyptians themselves so admired this complex, the name of the architect was remembered

through the centuries: Imhotep. Later Egyptians revered Imhotep as the architect and wise

counselor of the pharaoh Djoser and as a physician. In the Late Period he was deified; during the

Greco-Roman era he was identified with the Greek god of healing, Asklepios.

The funerary complex of Djoser developed the burial practices and tomb forms of the Archaic

period on a grand scale. The large area of 15ha, a rectangle oriented north–south, was enclosed

by a wall, 545m × 278m, made of small stones and decorated with “palace-façade” indentations

familiar from mud brick architecture and from the funerary enclosures at Abydos. Like many

elements of the complex, the wall has been restored in modern times. The walls have fourteen

apparent entrances, but only one is real, the south-east entrance. Dummy doors carved in open

position lead into a colonnade lined with twenty pairs of columns, each attached to the side

wall and carved with convex fascicles to resemble thick bunches of reeds. The ceilings origi-

nally resembled palm logs. Such details throughout the complex make clear an important source

for Imhotep’s creation, for they are all translations into stone of traditional architecture in less

durable materials: mud brick, wood, and reeds.

The colonnade eventually leads to a large court, bordered on the north by the Step Pyramid

that overlies the king’s burial, and on the south by a walled court that contains an underground

cenotaph, or dummy tomb, a simpler version of the northern burial. Such duplication of fea-

tures is one of the interesting aspects of the complex, perhaps reflecting the celebration of cer-

tain kingly rituals such as funerals in both Upper Egypt (at Abydos) and Lower Egypt (here at

Saqqara), as homage to the two regions perhaps still imperfectly welded into a single state. Now,

with two sets of buildings, the rites could be conveniently celebrated in this single location.

The large court contained two B-shaped markers, evidently used for a ceremonial race run by

the king during the important rite of rejuvenation, the sed-festival. The presence of sed-festival

paraphernalia in this funerary complex indicates that these ceremonies would be performed in

the afterlife as well. Related rituals also took place in the smaller Jubilee Court to the east, a long,

narrow space lined by dummy shrines housing statues of the gods that represented the nomes,

or provinces, of Upper and Lower Egypt.

North of the Jubilee Court lie two additional complexes of courts and buildings, possibly

representing administration buildings for Upper and Lower Egypt. Architectural details include

columns with fluting (vertical concave channeling), an early occurrence of a feature seen in later

Egyptian and Greek architecture. Just inside the doorway of the South Building, graffiti, in hier-

atic script, record the visit of New Kingdom tourists from Thebes some 1,000 years later.

The Step Pyramid itself dominates the entire complex. First conceived as a mastaba on a

square plan, the structure ended as a pyramid of six tall, unequal steps, rising to a height of 60m.

The stages of construction have been clarified by the limestone casings, the fine stonework

used as exterior surfaces for rubble cores, found at various points within the pyramid. The final

version was originally encased in Tura limestone, the high-quality limestone from nearby quar-

ries on the east bank of the Nile. The burial chamber, a granite-lined room measuring 2.96m ×

1.65m × l.65m, lay below the pyramid at the bottom of a shaft 28m deep, in the middle of a large

complex of corridors and rooms perhaps intended as an underground version of the royal palace

(Figure 5.13). Despite the depth of the burial and the protection of the labyrinthine corridors, the

grave was robbed, probably in the First Intermediate period.

North of the pyramid the ruins of the mortuary temples overlie the entrance to the corridor

leading to the burial chambers. In these temples rituals were performed for the king, to benefit

his spirit in the next life. Pyramids were generally entered from the north, an auspicious direc-

EGYPT OF THE PYRAMIDS 89

tion because of the presence there of the circumpolar stars

that the king would want to join, and because the rising of

Sothis, the Dog star, in the northern sky on 19–20 July sig-

naled the imminent arrival of the annual Nile flood and the

revitalization of farmlands.

The visitor with sharp eyes will note a tiny chamber

resembling a large rectangular box tilting backward against

the lowest of the six sloping steps on the north-east side of

the pyramid. The front wall is pierced by two small holes at

eye level; otherwise, there is no access. This chamber is the

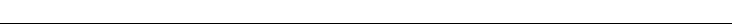

serdab. Inside was found a seated statue of Djoser (Figure

5.10), the original now replaced by a copy.

The statue had a precise religious function. It was

intended as the residence of the ka, one of the various souls

with which, according to ancient Egyptian belief, each mor-

tal was born. The ka was a person’s double, or “self,” the

life force animating the body; but when the person died, the

ka survived. It was free to move about, but needed a home

base. The corpse of the deceased, preserved by careful

wrapping and later, by mummification, was best, but statues

could serve perfectly well if they bore written identification

and were properly activated by such rites as the Opening of

the Mouth (see below). The two holes in the north wall of

this serdab allowed contact between the living and the dead,

and permitted the statue to enjoy such pleasures as the smell

of incense that might seep in.

The statue of Djoser, 1.42m in height, of painted lime-

stone, displays certain standard features of pose and cos-

tume that will continue for centuries. The king, identified by

his name carved on the base, sits stiffly, his feet together, on

a chair with a low back. He wears the cloak of the sed-fes-

tival, but the thin cloth reveals his body beneath. He also wears a royal wig and headdress, and

a long false beard, another symbol of kingship. His downturned mouth and his mutilated eyes,

once inlaid in separate materials, give him a grim look. Because the full mouth also occurs on

depictions of Djoser in relief sculpture, the image we see here must to some degree reflect the

actual appearance of this king.

TRANSITION TO THE TRUE PYRAMID

The purpose of the pyramid form is uncertain. Perhaps the pyramid represented the first land

that emerged from the waters, or a staircase to heaven, following indications in the Pyramid

Texts (ritual texts inscribed on the interior walls of pyramids beginning in the Fifth Dynasty), or

a solar symbol – or indeed all the above. Whatever its meaning, the form developed smoothly

from previous funerary architecture, from the mound heaped over early burials, to the mastaba

that encased a mound, to Djoser’s Step Pyramid, an elaboration enclosing a mastaba and ris-

ing from it. Other step pyramids are known from the Third Dynasty, but none has survived

Figure 5.10 Djoser, seated statue,

from Saqqara. Egyptian Museum,

Cairo

90 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

as well as Djoser’s. The change to the true pyramid, that is, a pyramid with smooth sides, took

place at the end of the Third and the beginning of the Fourth Dynasties. Built to shelter royal

tombs throughout the Old Kingdom, pyramids continued into the Middle Kingdom, with the

last major pyramids erected in Dynasty XIII at Mazghuna and Saqqara. But thieves always man-

aged to penetrate the pyramids and rob the burials. Because they failed in their prime mission,

the protection for the afterlife of the king’s body and belongings, during the New Kingdom

pyramids disappeared, replaced by tombs secretly cut out of the rock in remote locations on the

west bank at Thebes. Yet despite the precautions, virtually all these tombs, too, were robbed.

After the New Kingdom, the placement of royal burials changed again. Such tombs were now

located not in remote desert valleys, but in the precincts of urban temples.

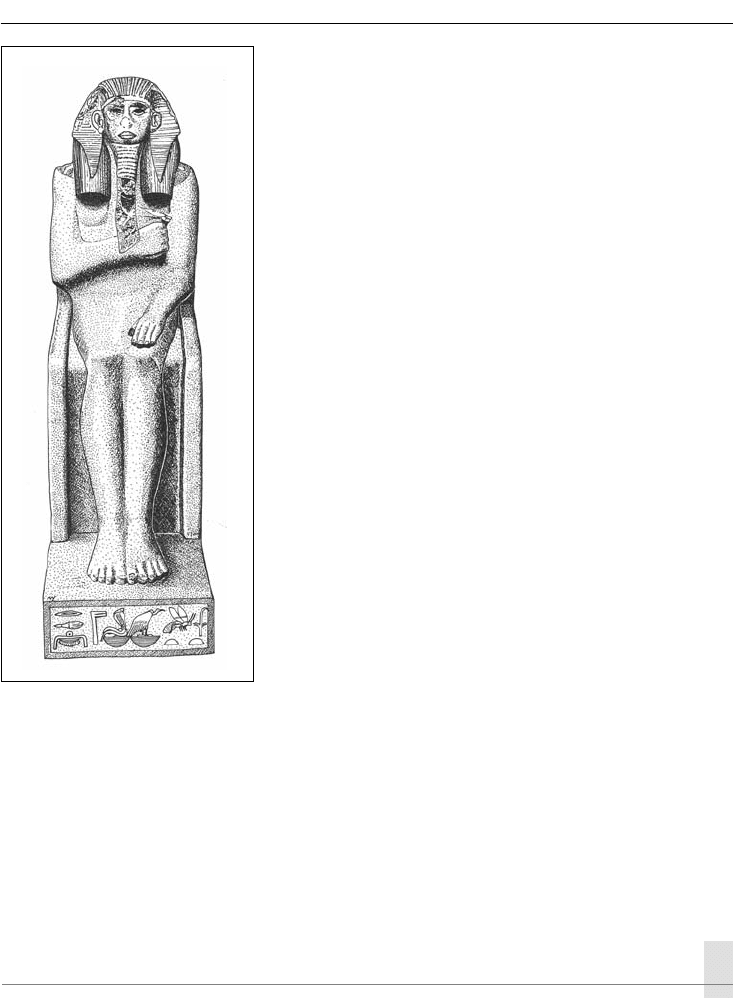

GIZA: A FOURTH DYNASTY FUNERARY COMPLEX

During the Fourth Dynasty, major royal tombs were constructed just north of Saqqara at Giza

– still close to the ancient capital, Memphis. Because of its three monumental pyramids and the

Great Sphinx, and its convenient location on the western outskirts of Cairo, Giza has long been

a prime destination for tourists (Figure 5.11).

The great pyramids

Three of the six kings of the Fourth Dynasty were buried here, Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure

(ca. 2575–2500 BC). In addition to the great pyramids that mark their burials, Giza contains

smaller pyramids for queens, temples devoted to the funerary cults, and a large number of

Figure 5.11 The Great Sphinx and the Pyramids of Menkaure (left) and Khafre (right), Giza

EGYPT OF THE PYRAMIDS 91

mastaba tombs, set out in rows, belonging to high officials and their families (Figure 5.12). The

size of the pyramids and the proximity of the mastaba tombs indicate the great prestige and power

of the pharaohs in this period. With their walls decorated with scenes of daily life, carved in low

relief sculptures and painted bright colors, these tombs have given important information about

Old Kingdom society. Also discovered at Giza are remains of the villages housing pyramid build-

ers and those who later maintained the area and serviced the cult needs of the many shrines.

Since little is known of the history of these rulers, these grandiose funerary monuments have

generated much speculation about the socio-economic conditions that promoted their construc-

tion. The building methods themselves are still debated. It has been proposed, for example, that

a step pyramid was erected first, with the steps later filled and the entire structure faced with

good-quality stone. Such hypotheses are difficult to test, however, for no one is about to disas-

semble these famous, well-preserved monuments to see how the inner blocks were laid.

Despite these difficulties, certain details of construction seem clear. After the rocky ground

was leveled, a limestone platform was constructed, the base for the pyramid. When the pyra-

mid was finished, it was enclosed by a low wall. The long sides were oriented to the cardinal

points, with the main entrance on the north. The interior was made of local limestone, the visible

exterior of high-quality limestone from Tura. Later pyramids might have cores of different

materials, rubble or even mud brick.

Figure 5.12 Plan, the Necropolis, Giza