Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

112 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Gem Aten (“Aten has been found”), a series of six open-air courts, each one smaller than the pre-

ceding. This building was surrounded by 365 offering tables on both the north and the south sides,

tied to the days in the solar year. Offerings were not strictly vegetarian, as the discovery of a butch-

er’s yard in the vicinity of the temple has made clear. Since much of the yard was open to the sky,

and since Egypt gets very hot, especially during the summer, performing ceremonies outdoors must

have been a strenuous task, the food offerings on the countless tables quick to spoil and smell.

The main temple lay in the east sector of the enclosure. In contrast with usual Egyptian prac-

tice, the main temple was not roofed but open air, because the Aten did not inhabit a statue in a

dark room, unlike other Egyptian gods, but manifested itself in the direct rays of the sun.

Houses

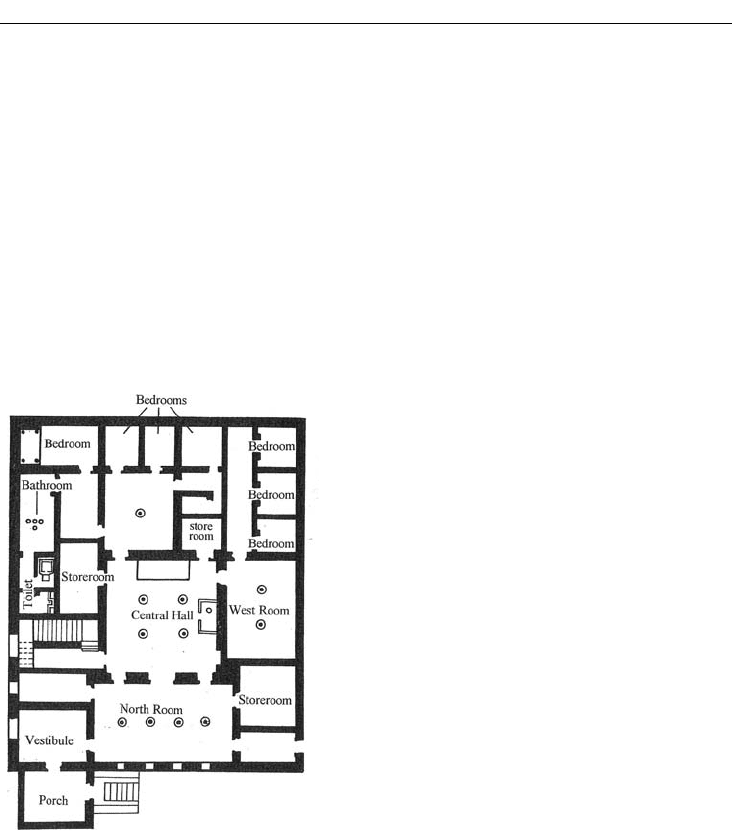

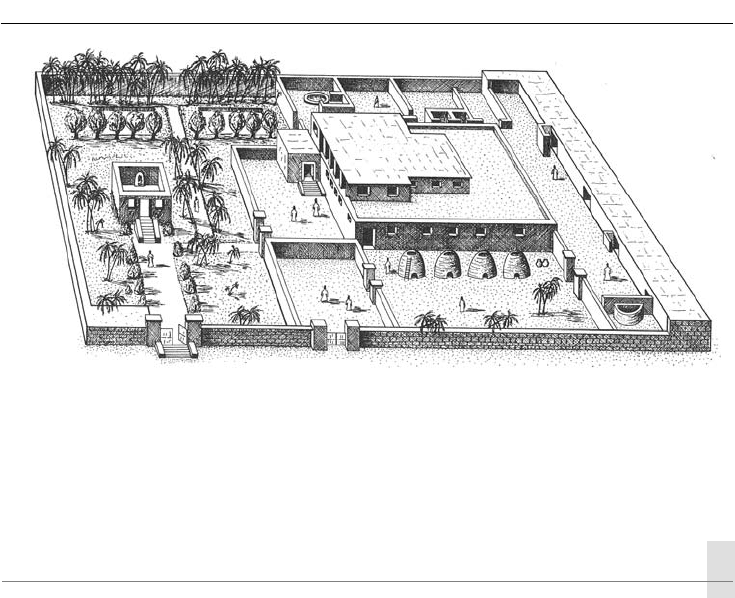

Amarna has given us fine examples of private free-standing houses of the well-to-do, in districts

to the north (North suburb) and south of the Central City (Figures 6.13 and 6.14). Their fea-

tures are fairly constant. Generally raised slightly on a

low platform, the typical house had a small entrance

room, followed by a larger two-storied loggia (“North

Room” on Figure 6.13) whose roof was supported

by wooden columns. A square hall lay in the center

of the house, insulated against extremes of tempera-

ture by surrounding rooms. Its ceiling, held up by

columns, rose above that of the adjacent rooms (with

the exception of the loggia), allowing for high win-

dows or clerestories immediately below the roof line.

The room might contain a low brick platform where

the owner and his wife would sit, a plastered stone

washing place for water jars, and a shrine to the Aten

and the royal family. Decoration was simple: plas-

tered walls, perhaps with painted geometric designs.

Off this main room lay smaller rooms, bedrooms,

toilets and bathrooms, storage rooms and stairs up

to the flat roof. Houses of the well-to-do were set

in a walled yard. Such compounds would contain a

well for water; a garden with trees, food plants, and

flowers; storage for grain and other food stuffs; ser-

vants quarters; kitchens (with circular clay ovens for

baking bread, open fires for the rest); a shelter for animals; and frequently a chapel to the Aten.

Sanitation remained primitive. There was no public drainage system at Amarna. Although bath-

rooms could be lined with stone, liquid wastes simply drained into the closest ground.

The end of Amarna

Upon Akhenaten’s death, the dynastic succession entered a period of turbulence. As tradi-

tional interests reasserted themselves, Amarna was abandoned in favor of Thebes, and the Aten

gave way to Amun. Eventually the state was salvaged by the general Horemheb and his vizier,

later Ramses I, the first of the family that would rule as the Nineteenth Dynasty. But between

Akhenaten and Horemheb briefly ruled a young king who would have been a mere footnote in

Figure 6.13 Plan, House, Amarna

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 113

the long list of Egyptian monarchs were it not for the almost miraculous survival of his tomb

virtually intact into the twentieth century: Tutankhamun.

THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS AND DEIR EL-MEDINA

Akhenaten was buried at Amarna, his now empty tomb identified by archaeologists. Virtually all

other New Kingdom monarchs were buried at Thebes, in a remote desert valley known as the

Valley of the Kings. This valley is but one part of the extensive Theban necropolis that lies on

the west bank of the Nile beyond the zone of cultivation.

The Valley of the Kings lies over the cliffs to the west of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

at Deir el-Bahri. Beginning with Thutmose I, most kings of the Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynas-

ties were buried here. Sixty-two tombs have been located, including some belonging to high offi-

cials. Many are decorated with wall paintings, but some are plain and some were never finished.

By the New Kingdom, the incidence of tomb robbery was high enough that kings were no

longer interested in visible signs that marked their graves, such as pyramids. Mortuary temples,

placed in the Nile Valley proper, would fulfill the desire for prestige as well as offering a setting

for the necessary ritual. The tomb itself had to be hidden, to ensure the survival of the pharaoh’s

body and his possessions. The workmen who carved out these tombs and decorated them lived

in a small, walled village, isolated from the rest of Thebes in order to keep their projects secret.

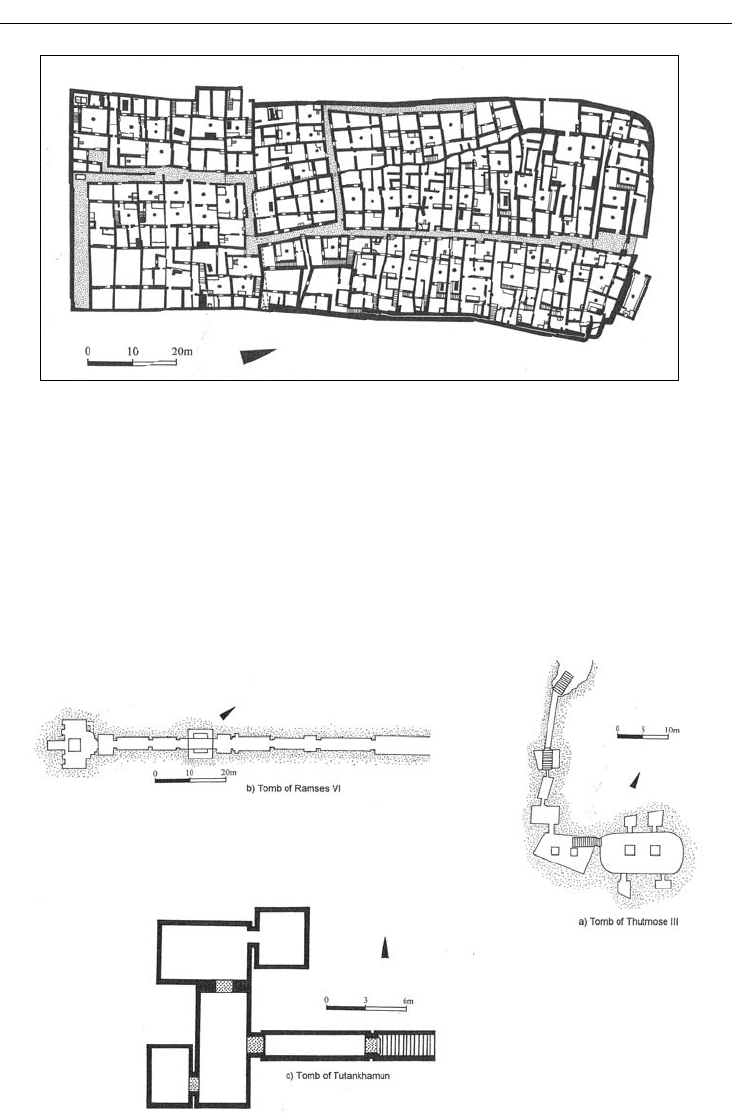

This village is today known as Deir el-Medina. The most important excavations of this site

were carried out by Bernard Bruyère, a French archaeologist, from 1922 to 1940 and, after the

Second World War, from 1945 to 1951. The plan of Deir el-Medina is rectangular, ca. 130m ×

50m, bisected lengthwise by a street with a dogleg plan (Figure 6.15). The house plans are known

from their well-preserved stone foundations. Houses were narrow, with rooms in a line, typi-

cally an entry room, a main room with a higher ceiling held up by one or two wooden columns,

a bedroom, and, behind a staircase leading to the rooftop, a kitchen. Excavations also yielded

thousands of ostraka, limestone flakes on which people wrote (in the cursive hieratic script) and

sketched; these documents have provided an exceptionally rich source of fascinating informa-

tion about the daily life of these workmen and their families.

Figure 6.14 House (reconstruction), Amarna

114 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings were laid out according to one of two ground plans. In

the first plan, followed in the first half of the Eighteenth Dynasty from Thutmose I to Amenho-

tep III, galleries arranged on a north–south axis descend along a gradual slope to a pit or well and

an offering chamber beyond. But the burial chamber, often a large oval in shape (like the royal

cartouche, the written form of the pharaonic name), lies to the west side, perpendicular to the

main axis of the galleries (Figure 6.16a: Tomb of Thutmose III). Later tombs preferred a second

plan, in which the galleries and burial chamber all lay along a single east–west axis (Figure 6.16b:

Tomb of Ramses VI).

Figure 6.15 Plan, Deir el-Medina

Figure 6.16 Ground plans of three tombs, Valley of the Kings, Thebes: (a) Tomb of Thutmose III;

(b) Tomb of Ramses VI; and (c) Tomb of Tutankhamun

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 115

The Tomb of Tutankhamun

The elaborate precautions taken to conceal the royal burials rarely sufficed. Only one tomb in

the Valley of the Kings was found substantially intact in modern times, the burial of the late

Eighteenth Dynasty king Tutankhamun (ruled ca. 1336–1327 BC), the young son-in-law, perhaps

also the son, of Akhenaten. Robbed twice in antiquity, although little was taken, the resealed

tomb was effectively hidden by the later construction of the adjacent tomb of Ramses VI, a king

of the Twentieth Dynasty. The discovery of the tomb in

November 1922 by British Egyptologist Howard Carter

represented the culmination of years of painstaking

examination of the already scrutinized valley. Ten more

years were needed to record the grave goods and remove

them from the chambers, and the scholarly publication

of the objects continues to this very day, long after Cart-

er’s death in 1939.

The Tomb of Tutankhamun differed from the stan-

dard type, but then it was originally destined not for

royalty but for an official. Upon the early death of the

king, it was hurriedly pressed into service. At the foot

of a descending passage lie four small unfinished rooms

(see Figure 6.16c), only one of which has wall paintings.

A tremendous array of objects was packed into this small

space. Included were statues of sentries, both human (in

the image of the king) and of Anubis, the jackal-headed

god who presided in cemeteries; furniture, such as chairs

and beds; hunting equipment, such as chariots, bows

and arrows; personal effects, such as gaming boards;

and food. Most of these are on display in the Egyptian

Museum in Cairo.

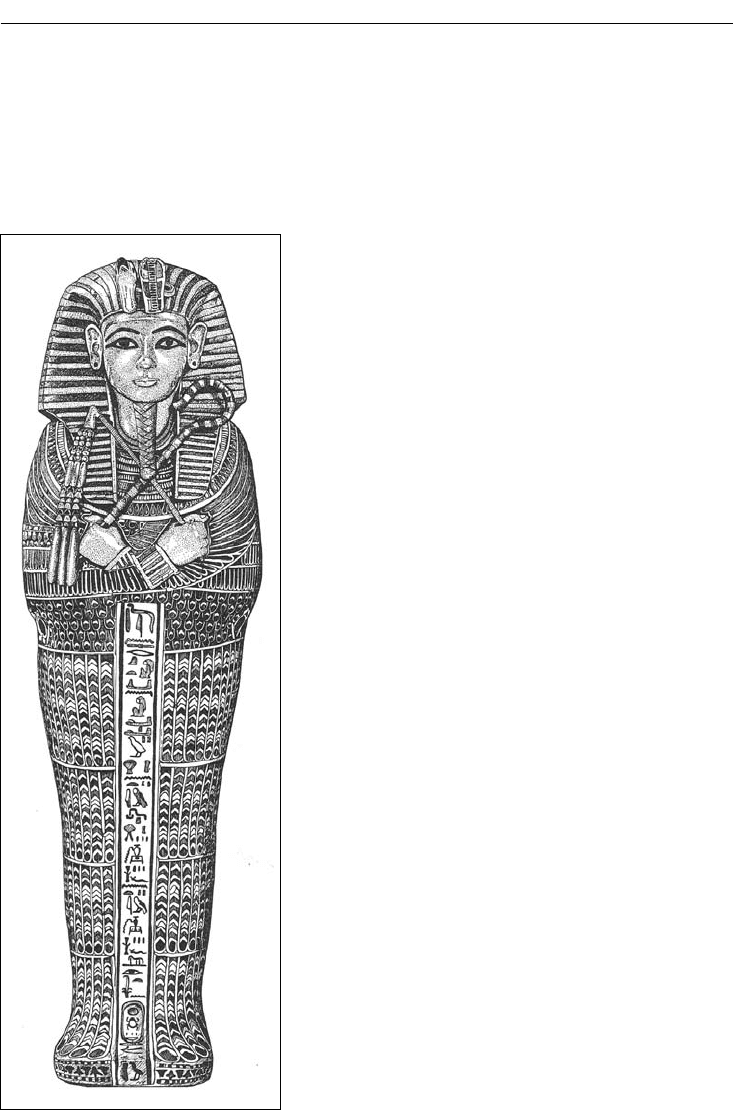

The king was only sixteen or seventeen when he died.

The cause of his death is unknown. He was buried inside

an elaborate complex of shrines and coffins that took

up most of the space in the burial chamber proper. Four

shrines covered with gold leaf, one inside the other, con-

tained a rectangular sarcophagus of yellow quartzite.

Inside the sarcophagus were found three anthropomor-

phic coffins, also one inside the other. The innermost

coffin was solid gold, weighing 110kg. Holes were left

for the eyes, however, so that the mummy could look

out. A mask of gold in the likeness of Tutankhamun,

inlaid with glass and lapis lazuli, provided further protec-

tion for the king’s head (Figure 6.17: this miniature cof-

fin for the organs imitates the full-sized middle coffin).

Tucked into the linen strips that wrapped the body was a

magnificent collection of jewelry and amulets. As for the

body itself, it has not fared so well; despite careful mum-

mification, the copiously used embalming fluids proved

corrosive rather than protective.

Figure 6.17 Coffin for the Organs,

Tomb of Tutankhamun. Egyptian

Museum, Cairo

116 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

THE NINETEENTH DYNASTY: RAMSES II AND

ABU SIMBEL

Although Ramses I ruled only two years, his descendants of the Nineteenth Dynasty continued

for another century (ca. 1295–1186 BC). His son, Seti I, and especially his grandson, Ramses II,

presided over a particularly powerful period in Egyptian history.

Ramses II is especially well known. He reigned sixty-seven years (ca. 1279–1213 BC), with

administrative centers at Thebes and at Per-Ramses in the Delta. He built some of the best

surviving and largest of Egyptian monuments, famously clashed with the Hittites, and has been

associated with the biblical story of the Hebrew exodus (this last is controversial). He avidly

promoted his own glory through his building projects, supplemented with wall decorations and

colossal statues of himself. We have already noted his additions to the Temples of Amun at

Luxor and at Karnak. One more monument of his merits our attention: the remarkable temple

at Abu Simbel, located in a remote spot near the southern frontier of modern Egypt.

This temple, and an accompanying smaller temple of his queen, Nefertari, were carved out of

the sandstone cliffs that lined the Nile in Nubia. Like the fort at Buhen, these monuments lay

in the region destined for flooding after the construction of the High Dam in Aswan. But these

temples met a kinder fate than Buhen: an international team under the aegis of UNESCO cut the

temples into blocks and reassembled them on dry land, some 210m inland and 65m higher.

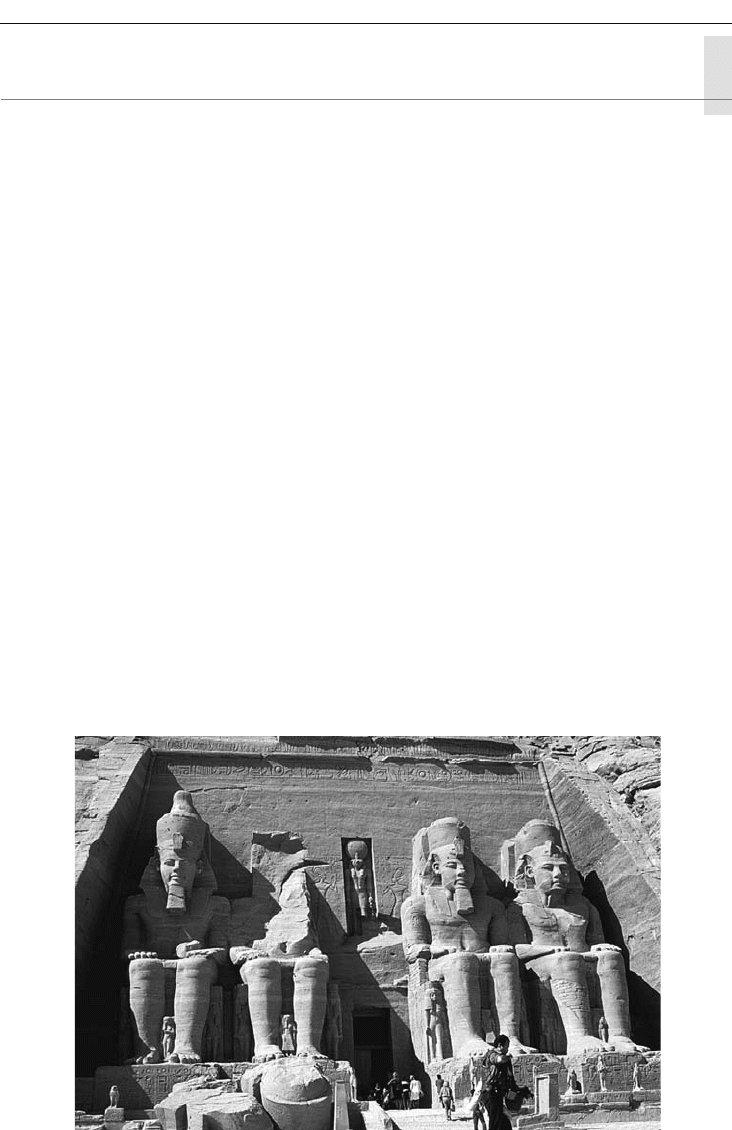

Ostensibly honoring the gods, in actuality this shrine at Abu Simbel glorifies Ramses II – a

monument to royal power exceptional even in a culture in which rulers rarely shrank from public

display of their greatness. The façade of the larger temple overwhelms the visitor with its four

colossal seated statues of Ramses II, each 20.1m high (Figure 6.18). Everyone else is smaller

and subordinate: the wives and children who stand by his lower legs, the prisoners paraded

beneath his chair in front of the entrance, even the god Re-Harakhte placed above the doorway.

Inside, the temple consists of four rooms on axis, a larger hall, a smaller hall, a vestibule, and the

sanctuary. Several side chambers, probably used as storerooms, lie off this axis. The large hall is

Figure 6.18 Exterior, Temple of Ramses II, Abu Simbel

EGYPTIAN CITIES, TEMPLES, AND TOMBS 117

dominated by two rows of columns carved with the standing likeness of the king as Osiris, the

important god of the afterlife. The side walls show reliefs of the king’s military triumphs, includ-

ing the Battle of Qadesh fought in Syria against the Hittites. Scholars believe this battle was actu-

ally a stand-off, but Ramses II had no interest in being objective about the result. The sanctuary

at the rear contains four seated states, Ramses II and three major gods, Re-Harakhte, Amun, and

the supreme god of Memphis, Ptah. The temple was aligned so that twice a year, in February and

October, the sun’s rays would reach the rear of the temple and shine on the three gods and the

pharaoh. The first date may correspond to Ramses II’s coronation day, or perhaps the date of his

first jubilee, since the temple was built to celebrate this event.

AFTERMATH

The Egyptian kingdom prospered through the early twelfth century BC. Two kings, Merneptah

of the later Nineteenth Dynasty, and Ramses III, the greatest ruler of the Twentieth Dynasty,

fought off foreign challengers, the Libyans from the north-west, and the Sea Peoples, an enig-

matic coalition of peoples from south-east Europe and western Asia who had already caused

great destruction in the coastal cities of the eastern Mediterranean. In traditional fashion, the

triumphs against the Sea Peoples are recorded in the relief sculptures on the walls of the massive

mortuary temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu, Thebes. Ramses III was succeeded by eight

more kings of that name. None would match his greatness, and once again the Egyptian kingdom

would feel the weakening of central authority. The New Kingdom was followed by the Third

Intermediate Period and the Late Period, Dynasties Twenty-one to Thirty, the final dynasties of

Manetho’s list. Dynastic Egypt ended with a second brief occupation by Persians, themselves

overcome in 332 BC by a greater conqueror, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great. Egypt

then passed into the world of the Greeks and the Romans, first pagan, later Christian. After 3,000

years, pharaonic culture was slowly extinguished.

CHAPTER 7

Aegean Bronze Age towns and cities

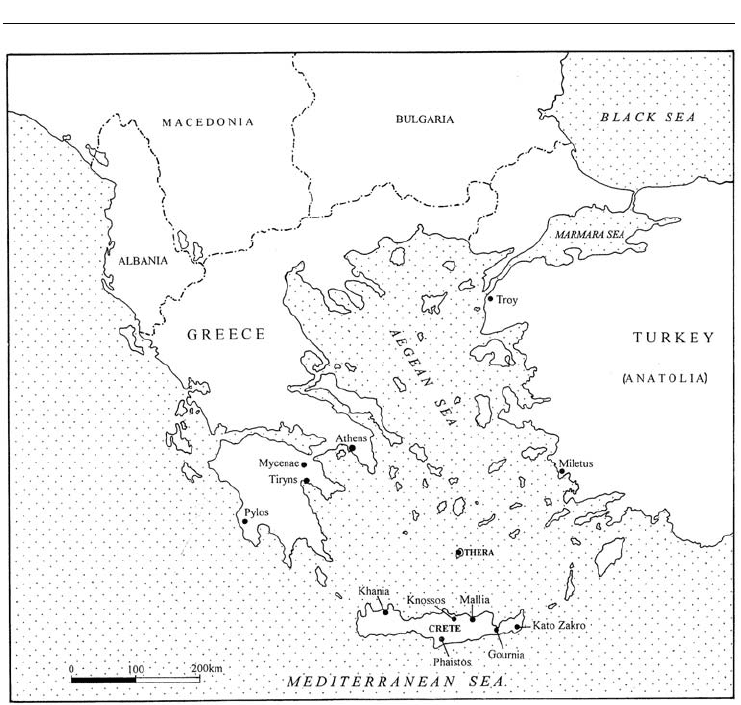

AEGEAN CIVILIZATIONS AND CITIES

In Mediterranean archaeology, the term “Aegean” refers to the Neolithic and Bronze Age cul-

tures of the lands that borders the Aegean Sea, and the Aegean islands, lands now belonging to

modern Greece and Turkey (Figure 7.1). These cultures first came to scholarly attention in the

second half of the nineteenth century, especially with the discoveries of Heinrich Schliemann,

a businessman interested in ancient history. Determined to discover historical truth behind the

Greek legends of the Trojan War, Schliemann excavated some of the important towns participat-

ing in the drama, Troy, Mycenae, and Tiryns (see also Chapter 8). On Crete, large-scale excava-

tion became possible by 1900 when the island was newly freed from the Ottoman Empire; within

a decade the main characteristics of the distinctive Bronze Age culture of Crete were clear. This

culture was dubbed “Minoan” by Arthur Evans, the excavator of Knossos, after Minos, the

Minoan Crete:

Old Palace (Protopalatial) period: ca. 1930–1700

BC (= Middle Minoan IB-II)

New Palace (Neopalatial) period: ca. 1700–1450

BC (= Middle Minoan III,

Late Minoan IA and B)

ca. 1450

BC, most sites destroyed, with

the major exceptions of Knossos

and Khania.

Late Minoan II: ca. 1450–1400

BC

Probable Mycenaean occupation at Knossos and Khania

Post-Palatial: ca. 1425–1050

BC (= Late Minoan IIIA,

B, and C)

Major destructions at Knossos ca. 1375

BC and probably ca. 1200 BC

Thera (Santorini): Volcano erupts ca. 1520 BC

Mycenaean Greece:

Middle Helladic (late) ca. 1650–1500

BC

and Late Helladic I:

Shaft Graves at Mycenae

Late Helladic II: ca. 1500–1400

BC

Late Helladic IIIA: ca. 1400–1340 BC

Late Helladic IIIB: ca. 1340–1185 BC

Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae; Citadels at Mycenae and Tiryns; Palace at Pylos

Late Helladic IIIC: ca. 1185–1050

BC

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 119

legendary king of the island. On mainland Greece, the Late Bronze Age culture that flourished in

its southern and central sections is called “Mycenaean,” after the city of Mycenae. A spectacular

new chapter in Aegean prehistory was opened in 1967 with the first large-scale excavations at

Akrotiri, a settlement on the Aegean island of Thera, well preserved under the volcanic debris

from the eruption of the island that may have taken place around 1520 BC.

Although the names of many Bronze Age cities are well known, thanks to the literature of the

later Greeks, the nature of Aegean urbanism is not well understood. With a few notable excep-

tions, excavations have focused on certain monumental elements of the city, such as palaces,

villas, and citadels, or on tombs, their design and their contents. Moreover, the textual evidence is

limited: the written documents surviving from the Bronze Age Aegean, when they can be clearly

understood, record a limited range of subjects. However, if we consult Childe’s definition of a

city (see Introduction), it seems likely that the main settlements were indeed cities. All criteria

from his list are clearly met, with the one possible exception of the practice of exact and predic-

tive sciences, as yet unconfirmed. Our look at Minoan, Theran, and Mycenaean cities and towns

will follow the lead of traditional research concerns. Nonetheless, we will want to keep in mind

that future investigation has much to reveal about how these striking structures and finds relate

to the overall settlements of which they form a part.

Figure 7.1 Aegean Bronze Age towns, second millennium BC

120 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

CRETE: KNOSSOS AND THE MINOANS

Crete is the largest island of modern Greece, about 200km long and, at its maximum, 58km wide.

It sprawls at the southern end of the Aegean Sea, the last landfall between Greece and Africa. The

Cretan landscape combines rugged mountains with pockets of fertile agricultural land, while its

Mediterranean climate features rainy, chilly winters and long hot, dry summers.

Minoan history

In the absence of legible records – the “hieroglyphic” and Linear A scripts used by the Minoans

are imperfectly understood – the history of the Minoans still has many mysteries. During the

New Palace period, the high point of Minoan civilization, the Minoans seem to have controlled

the southern Aegean, including the coastal regions of south-east Greece and south-west Anatolia

(Turkey). The New Palace period ended ca. 1450

BC in a wave of destruction, the cause of which

is uncertain. The Mycenaeans of mainland Greece either contributed to or profited from the col-

lapse. They were on the ascendant, and apparently occupied Knossos and Khania (the important

town in as yet little explored western Crete) at this time. They took control of the Minoan ter-

ritories in the southern Aegean, and probably continued their occupation of Crete through the

Late Bronze Age, imposing their own language (the earliest known form of Greek) and writing

system (the Linear B script) as the medium of administration. The remains of this period, the

fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BC, are poorly known, with the history of Knossos being

particularly controversial.

Knossos: The Palace of Minos

The palace is the hallmark of Minoan architecture. The term “palace” is misleading, it must be

stressed. “Palace” suggests a royal residence. For Minoan Crete, we are unsure who the rulers

were. The later Greeks wrote of a King Minos (see below), but from the Bronze Age itself,

evidence for the rulers – pictorial, textual, or other – is absent. Nonetheless, the term “palace”

is entrenched in the archaeological literature; it is best to divorce the palace from royalty and,

instead, to consider it a large architectural complex housing a variety of functions.

Four large palace complexes are known from Bronze Age Crete: Knossos, Mallia, Phaistos,

and Kato Zakro. Smaller structures, comparable in design and built of the same ashlar masonry

technique, have been discovered at Galatas, Gournia, and Petras. Of these, Knossos is the largest

and most important, and has yielded examples of most characteristic features of Minoan civili-

zation. Indeed, so dominant was its position in Cretan culture from the Neolithic through the

Bronze Age that archaeologist Jeffrey Soles has persuasively identified it as a cosmological center:

a focus of cultural origins, a wellspring of human and divine energy and cultural creativity.

A sustained campaign of excavation began in 1900. Arthur Evans, then fifty years old, had

the good fortune to live another forty-one. He was able to present his findings in a magisterial

four-volume publication, The Palace of Minos. Not only did he expose the palace and several of

the outlying buildings, he also restored portions of the architecture and numerous objects so the

public could have a better understanding of the remains. These restorations, virtually impossible

to dismantle, are now viewed by scholars as a handicap, for they make it difficult to imagine

the evidence in its original state at the time of discovery – important for any re-evaluation of its

significance.

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 121

Although occupation began at Knossos during the Neolithic period and continued through

the Bronze Age and indeed well beyond, the ruins one sees today are largely from the heyday of

the palace in the New Palace Period and the ensuing seventy-five years, ca. 1700–1375 BC. The

terminology for the different phases of Minoan civilization can be confusing, because two sys-

tems are used, each serving a useful purpose. The original framework designed by Evans divided

Minoan culture into three periods: Early, Middle, and Late Minoan, with further subdivisions

(I, II, and III; A and B). Although it continues to serve well the study of pottery development,

this system does not correlate with the major breaks in the architectural sequence. To highlight

these events, a second system was devised: the Pre-Palatial (= Early Bronze Age), Protopalatial

(= Old, or First, Palace), Neopalatial (= New, or Second, Palace), and Post-Palatial periods. The

correspondences between the two systems are given in the introductory chart on page 118.

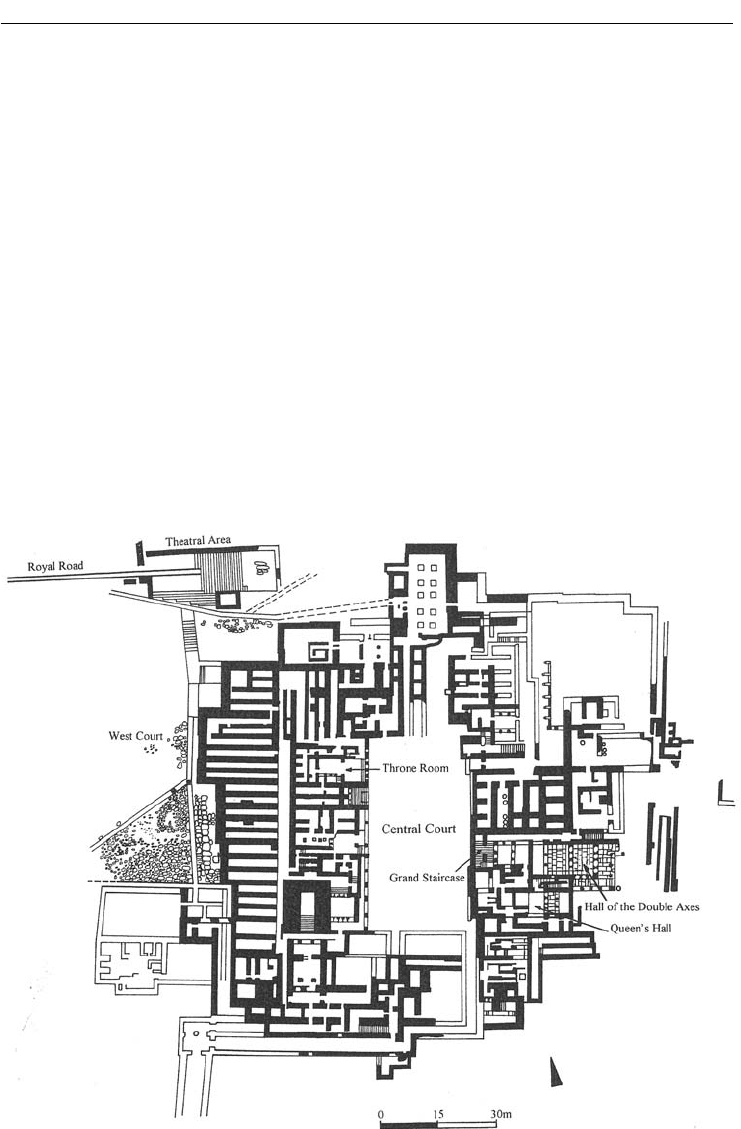

The palace occupies an area of 1.3ha on a low hilltop in a well-watered valley some 10km from

the sea, not far from the modern city of Heraklion (Figure 7.2). The site is unfortified; indeed,

the lack of fortification walls is a striking feature of Minoan towns and palaces during the New

Palace period. Only Mallia has yielded a hint of a city wall, nothing more. This absence of fortifi-

cations suggests an age of political harmony throughout the island, perhaps under the leadership

of Knossos.

The palace complex served many functions, such as residence (although we are not sure who

resided here), seat of administration, treasury, depot for agricultural and manufactured products,

Figure 7.2 Plan, The Palace of Minos, Knossos