Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

132 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Minoan Crete had lost its political independence. Certain motifs, however, are specifically Myce-

naean in taste, not Minoan; for example, the scenes of hunting and warfare mentioned above.

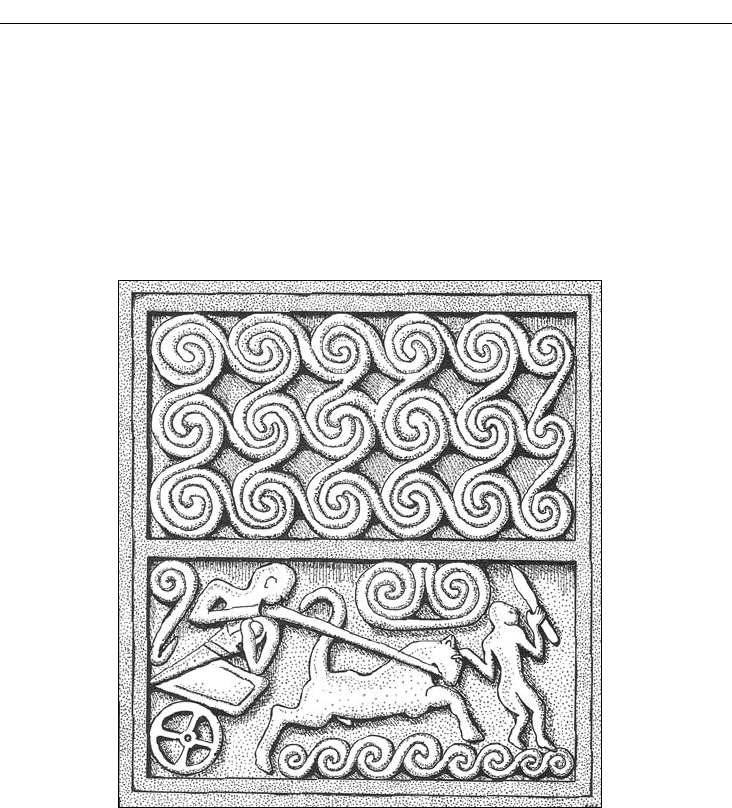

The grave stele found over Shaft Grave V exemplifies this, with its crude but animated carving

of a horse, chariot, charioteer, and servant, bordered by thick bands of spirals (Figure 7.14).

Despite its feline tail, the creature shown does indeed seem to be a horse, which reminds us that

the horse had only recently entered Greece, sometime in the Middle Bronze Age, long after its

fellow domesticates, the sheep, goat, pig, and cow. The horse, an import from central or western

Asia, may be an authentic sign of migrating Indo-Europeans.

The Treasury of Atreus

By the fifteenth century BC, the burial form of choice for the top of Mycenaean society was no

longer the shaft grave but the tholos tomb. As we shall see, tholoi (pl. of tholos) are elaborate

structures. For ordinary citizens, the chamber tomb sufficed, a room cut out of the rock.

The Greek word “tholos” means a round building, and is applied to round structures serving

a wide array of functions from all periods of Greek antiquity. In the Mycenaean world, tholoi are

round dome-shaped tombs built of fieldstones or, exceptionally, well-cut stone masonry, laid in

the corbelling technique (see Figure 2.18), and then buried, so the earth will provide the neces-

sary counterpressure for the corbelling.

Mycenaean tholoi are first attested in Messenia, but the largest and best known are at

Figure 7.14 Grave stele; Shaft Grave V, Grave Circle A; Mycenae. National Archaeological Museum,

Athens

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 133

Mycenae itself. The best preserved of the nine tholoi at Mycenae is the so-called Treasury of

Atreus, a misnomer bestowed already in Classical antiquity. Dating of tholoi is difficult

because most of them were stripped of their contents in antiquity. On the basis of the masonry

techniques and a deposit of datable pottery found under the threshold, this tomb is placed

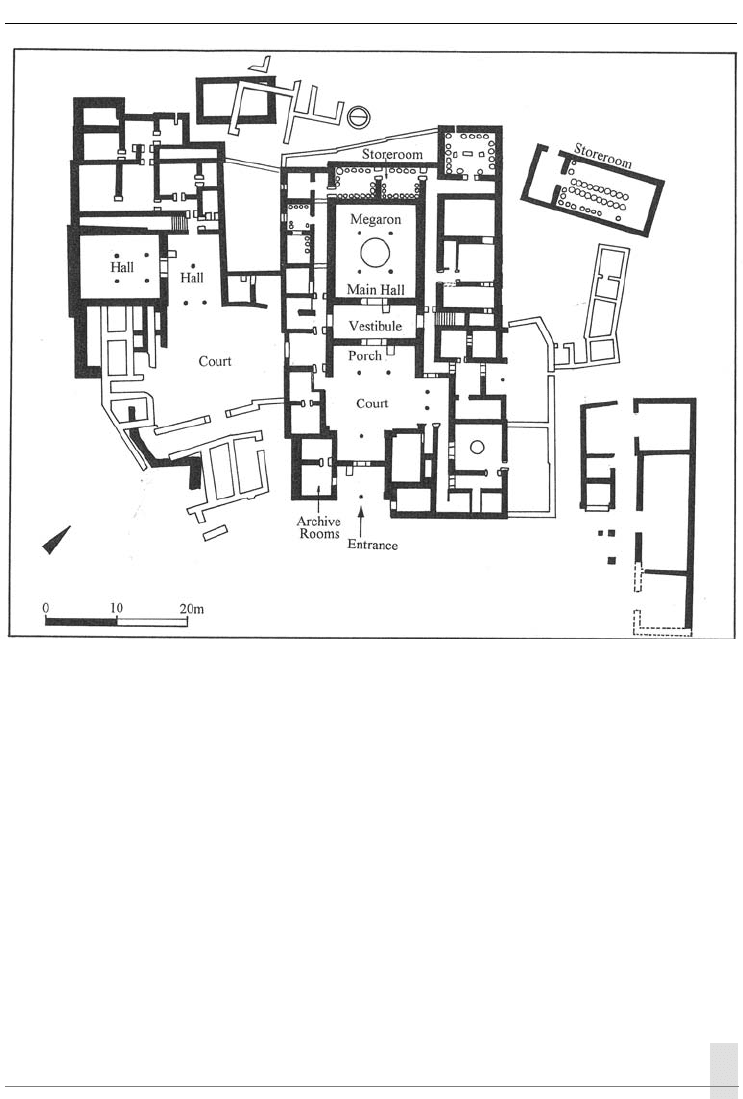

fairly late in the series, ca. 1300 BC. A dromos, or entrance way, 36m long and lined with fine

masonry, leads up to the round tomb chamber (Figure 7.15). It is not known whether the

dromos remained clear in antiquity, so one could see the great doors, or whether it too was

hidden under earth.

One passes through the grand doorway, originally closed with double doors of wood with

bronze fittings, and flanked by half columns of green stone (lapis Lacedaemonius) that rose in

two tiers. Red porphyry was used for a triglyph and half-rosette frieze in the upper story. Two

massive lintel blocks form the top of the doorway. The larger inner block measures over 8m long

and weighs more than 100 tons. To relieve pressure, a triangular space above the lintels was left

empty; masked by the frieze just mentioned, it was invisible from the exterior. This feature is

called the “relieving triangle.”

The interior is 14.5m in diameter at the base, 13.2m in height. Horizontal rows of nail holes

suggest gilded bronze rosettes may have decorated the walls. The Treasury of Atreus is unusual

in having a side chamber, hewn out of the bedrock. The burials would have been in pits in the

floor, to judge from intact examples from other sites, in this case probably in the side chamber.

Not a trace has survived. Interestingly, a virtually identical tomb, although less well-preserved,

the so-called Treasury of Minyas, was discovered quite some distance away at Orchomenos in

Boeotia (central Greece). It may well have been the work of the same architect.

Figure 7.15 Dromos and entryway, Treasury of Atreus, Mycenae

134 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

The citadel

Fortified citadels are characteristic of the Mycenaean centers, especially in the coastal regions of

the eastern mainland of Greece. Strong walls protected the nucleus of the settlement. Like the

Minoan palace, this core served a variety of activities, administrative, economic, and religious.

Unlike the Minoan palace, these purposes were carried out in separate buildings. The most nota-

ble of the buildings is the palace, but the Mycenaean palace differs from its Minoan counterpart

in several important respects.

The bulk of the populace lived outside the walls. No comprehensive town plan has been

recovered from the Mycenaean world, nothing comparable to Gournia, say, on Minoan Crete.

But surface surveys conducted in many areas of central and southern Greece have revealed abun-

dant traces of Mycenaean presence. The Mycenaeans had an extensive system of roads; other

civil engineering projects, such as the securing of water supplies, large-scale drainage, and dams,

have also been located by archaeologists. The best-known project, the draining of the low-lying

Copaic basin in Boeotia and protection of the land from encroachment by the sea with a series of

dikes, still seems an astonishingly ambitious undertaking for the Bronze Age Aegean.

The citadel walls at Mycenae, 900m in perimeter, enclose an area of ca. 38,500m

2

. The walls

seen today were built in the LH IIIA and B periods. The main entrance is in the north-west (see

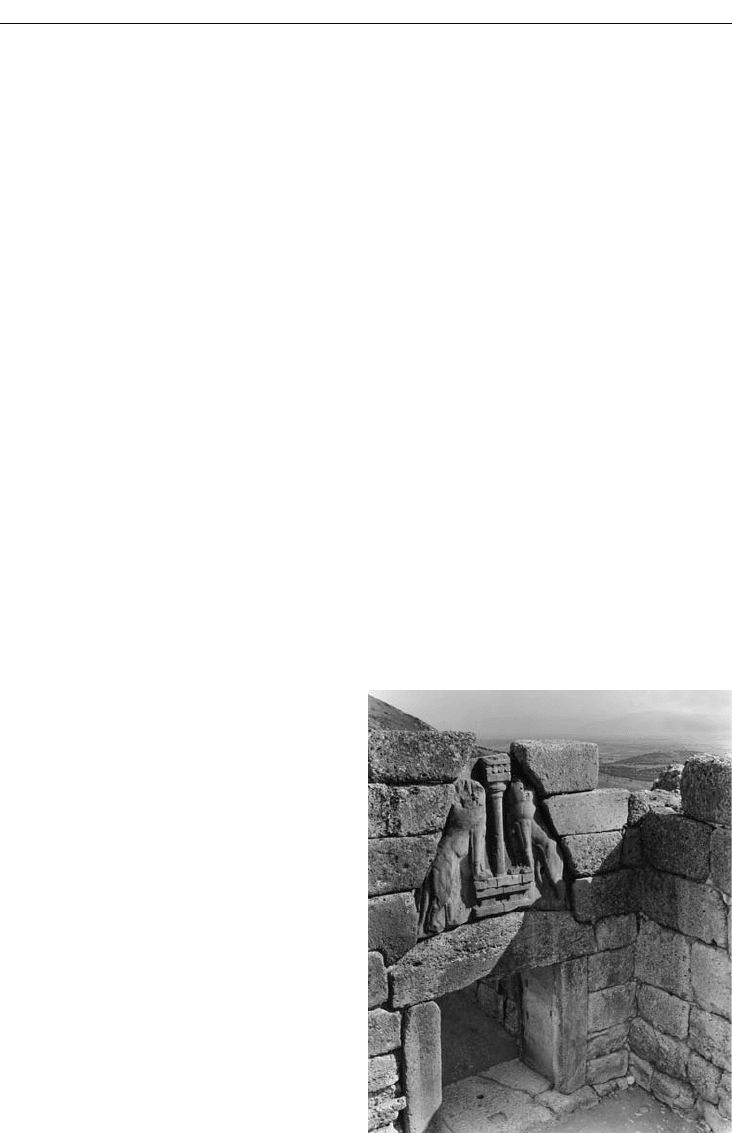

plan, Figure 7.12), the Lion Gate. This gate, erected in the thirteenth century BC, was made of four

enormous blocks of local conglomerate, comprising the threshold, the two jambs, and the lintel.

Round cuttings can be seen in the lintel and threshold blocks for the fitting of door posts onto

which door leaves were attached, and in the jambs for a horizontal bar to insert behind the closed

gates. Above the lintel is a relieving triangle covered in front with a striking relief sculpture of

two lions in a heraldic pose, their forepaws resting on a pair of altars supporting a single column

(Figure 7.16). The lions give their name to the gate. Their heads are missing, however. The possi-

bility therefore exists that these animals were griffins, mythical protective beasts with the heads of

eagles and the bodies of lions. Such griffins

were earlier depicted by the Minoans in the

frescoes that flank the carved stone seat in

the Throne Room at the Palace of Minos at

Knossos. The Mycenaeans featured them as

well, notably at the palace at Pylos.

The citadel walls contain different types

of masonry, easily distinguished by the visi-

tor today. These include coursed conglom-

erate ashlar, used at the Lion Gate; Cyclopean

masonry, that is, huge blocks crudely fitted

with tiny stones filling the interstices; and

a rusticated limestone polygonal masonry,

employed much later in Hellenistic times.

Cyclopean masonry received its name from

the later Greeks who believed that only

giants such as the Cyclopes could wield such

large stones. Cyclopean masonry is also seen

at Hattusa, the Hittite capital – a puzzling

coincidence, considering that links between

the Mycenaeans and the Hittites are other-

wise rare.

Figure 7.16 The Lion Gate, Mycenae

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 135

By the mid- to late thirteenth century BC the fortified enclosure was completed, an enlarge-

ment of the earlier citadel. Also refurbished at this time was Grave Circle A, with a circular

parapet constructed around the much earlier Shaft Graves. Notable among the buildings inside

the citadel are a series of shrines discovered in the south-west sector of the citadel, including

the Room with the Fresco and the House of the Idols, small dark rooms with, respectively, wall

paintings and grotesque clay figurines of humanoids and coiled snakes. Such small rooms, all

that Mycenaean sites have so far yielded in terms of temples, recall the shrines in Minoan pal-

aces. Names of divinities revealed on Linear B tablets include gods familiar from the later Greek

period, such as Zeus, Hera, and Poseidon.

The ground rises steeply from the Lion Gate. The highest ground within the walled citadel

was occupied by the palace, as was typical. Due to its lofty and exposed location, the palace at

Mycenae has largely eroded away. The tourist standing amidst its fragmentary ruins must content

him or herself with the magnificent view over the Argive plain. For a clearer understanding of the

layout of a Mycenaean palace, one must travel across the Peloponnesus to extreme south-west

Greece, to Pylos in Messenia.

Pylos: the Palace of Nestor

In 1939, American archaeologist Carl Blegen discovered a Mycenaean palace at Ano Englianos,

a hilltop overlooking the Bay of Navarino to the south, not far from the modern town of Pylos.

Under the influence of Homer, Blegen attributed the palace to Nestor, the wise ruler of Pylos in

the Iliad and the Odyssey. Although the place is named (PU-RO) in several of the many Linear B

tablets found here, Nestor is not, so Blegen’s leap of faith must be regarded with caution.

The palace we see today was built largely in the thirteenth century

BC, in the LH IIIB period,

and burned ca. 1200 BC. This palace did not have a fortifi cation wall, most unusual for a Myce-

naean center. Evidently it had no rivals in its immediate vicinity, unlike Mycenae. Its destruction

would be the work of invaders from afar. Indeed, the palace served as the nerve center for a large

area in south-west Messenia, a region whose history from the Bronze Age to the present was

documented in the 1990s by an ambitious multi-disciplinary survey project, the Pylos Regional

Archaeological Project (PRAP, for short).

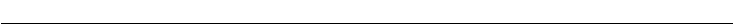

The palace is small, only a quarter the size of the palace at Knossos (Figure 7.17). Walls were

built of rubble cores reinforced with a timber framework, and faced with pale limestone ashlar

masonry. One enters through a modest gateway, flanked by two archive rooms on the left (find

spot of ca. 1000 Linear B tablets and fragments) and a possible tower on the right. After pass-

ing through a small court, one reaches the distinctive core of this and all Mycenaean palaces,

the megaron. “Megaron” is the word used in Homer to denote the great hall. From Schliemann

on, Classically minded archaeologists have attached this word to a variety of hall-like rooms. In

Mycenaean architecture the word has assumed a distinct meaning. The Mycenaean megaron is a

unit of normally three rectangular spaces, arranged along a single axis: a porch, a vestibule, and

a much larger main room. At Pylos, the main room would have been attractive, although dark

and smoky. Dominating the room is a large, low circular platform: a hearth. The hearth rim was

repeatedly coated with lime plaster and painted with spirals, its sides with flame patterns. The

floor and walls of the room were plastered and decorated with frescoes. Four wooden columns,

arranged around the hearth, held up the ceiling. The columns have long since vanished, but the

small round holes into which they were inserted can still be seen, preserved by the plastered floor

laid around them. Also gone is the roofing, of branches, twigs, and clay, but the broad clay pipes

136 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

through which smoke from the fire on the hearth escaped have survived. What sort of windows

might have existed, if any, is unknown. In the floor along the north wall is a cutting for a wooden

chair, probably similar in design to the stone chair in the Throne Room at Knossos. Next to this

is a curious and unexplained hollow in the plaster floor, two small basins connected by a curved

groove.

The megaron is surrounded by rooms devoted to the important economic activities of the pal-

ace. As the Linear B tablets attest, the palace was the center for the collection and redistribution

of the agricultural produce and manufactured products of the region. Storerooms for wine, olive

oil, and grain have been identified, as have workshops for smiths, masons, and the manufacture

of perfume. The palace has also yielded much pottery. In one room, 2,853 stemmed drinking

cups were found, leading Blegen to joke that Nestor, an august figure in the Homeric poems, was

a dealer in kitchenware.

THE END OF MYCENAEAN CIVILIZATION

The Palace of Nestor was destroyed ca. 1200 BC. The people responsible are unknown, but the

destruction fits in with a pattern of disasters that overwhelmed the established cultures of the

eastern Mediterranean in the late thirteenth and twelfth centuries BC. At Mycenae and the neigh-

Figure 7.17 Plan, Palace of Nestor, Pylos

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 137

boring fortress of Tiryns, impending danger is seen in the citadel architecture. At both sites, the

inhabitants secured their supply of water by enclosing a spring within a new north-east extension

of the walls (Mycenae) or digging an underground passageway from within the citadel to the

spring just outside (Tiryns). Mycenae underwent a series of challenges during this period. Invad-

ers were perhaps responsible, but local unrest may also have contributed, perhaps stimulated by

climate changes and crop failures. Whatever the reasons, by the end of the twelfth century BC the

sophisticated economic and social system based on the palaces and citadels and their dependent

cities, with records written in Linear B, had collapsed. The Aegean basin reverted to a village-

based economy, with little external trade and few luxuries. Self-sufficiency became the byword

of the Greek Dark Ages.

CHAPTER 8

Anatolian Bronze Age Cities

Troy and Hattusa

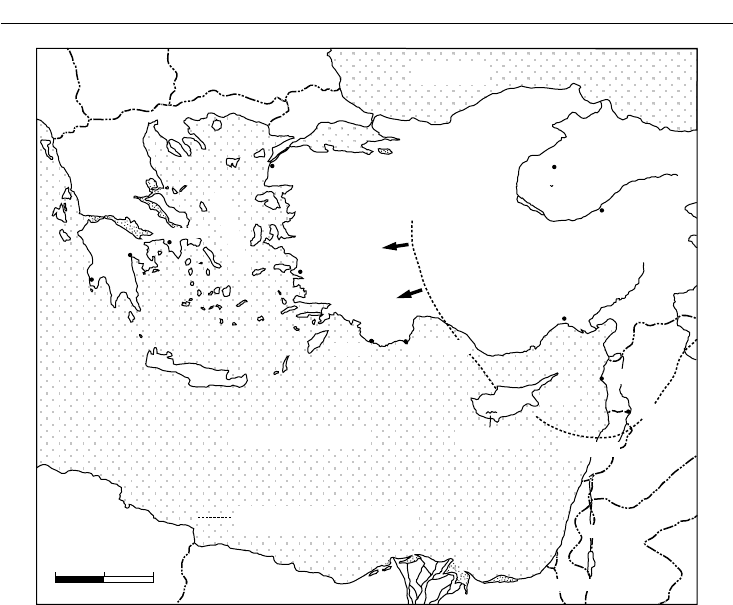

The term Anatolia, derived from the Greek word for “east,” is commonly used to denote the Asian

territory of modern Turkey in pre-Classical antiquity. Anatolia is divided into two geographical

zones: the coast and the interior. The coastal zones have a moderate climate, with cool, rainy

winters and hot, rainless summers, whereas the interior plateau, at an elevation of 1000m, has a

continental climate with snowy winters and dry summers. The geographical distinctions between

the two areas have been accompanied by cultural differences even down to the modern day. Cit-

ies of the coast have looked across the seas for their livelihood, while the interior has depended

on its conservative self-contained farming and craft traditions. Two well-known cities of Bronze

Age Anatolia illustrate the dichotomy between these two regions: Troy, in the coastal region of

north-west Anatolia, and Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites, in the central plateau (Figure 8.1).

TROY

Troy is one of the most famous cities of Mediterranean antiquity. The war supposedly fought

here between the Trojans and the Mycenaeans (or Achaeans, as Homer called them) occupied

a preeminent place in the consciousness of the ancient Greeks, with the works of countless

writers, sculptors, and painters bearing witness to the pull of this dramatic conflict. The archae-

ological evidence, however, presents a Troy rather different from that described in the liter-

ary sources. We should see this discrepancy not as a roadblock but as a fascinating intellectual

problem: how should we interpret the complementary but often conflicting contributions that

Troy:

Troy I: ca. 2900–2400

BC

Troy II: ca. 2400–2100

BC

Troy III–V: ca. 2100–1800

BC

Troy VI: ca. 1800–1300

BC

Troy VIIa: ca. 1300–1260

BC

Troy VIIb 1: ca. 1260–1190

BC

Troy VIIb 2: ca. 1190–1100

BC

The Hittites:

Old Hittite Kingdom: ca. 1575–1400

BC

Middle Kingdom: ca. 1400–1350 BC

Hittite Empire: ca. 1350–1200 BC

ANATOLIAN BRONZE AGE CITIES 139

literary and archaeological evidence make to our understanding of antiquity?

If we follow the indications of the ancient Greeks, the war must have taken place during what

we call the Late Bronze Age. No contemporary accounts of the war exist. Some modern scholars

have even doubted whether this conflict took place at all, considering it instead a myth developed

by later Greeks to flesh out their remote past. The question is difficult to answer. Most probably

the story contained a kernel of truth, even if the actual events were much distorted in the telling.

What that kernel might be has been much debated, and with it, the explanation of the archaeo-

logical site of Troy.

The site came to public attention in the mid-nineteenth century with the excavations of Hein-

rich Schliemann. Schliemann (1822–90), the son of a German pastor, made a fortune in business

in Russia and in the United States. Since childhood, or so he claimed, he cherished an obsessive

interest in the Iliad and the Odyssey, the great epic poems of Homer. Against prevailing scholarly

opinion, he believed the poems had a basis in reality, and he determined to prove it. In 1870,

he obtained a permit from the Ottoman government and began excavations at the mound of

Hisarlık in north-west Turkey, the site he equated with the Troy of Homer. Although contro-

versy still surrounds the accuracy and honesty of his reports, it cannot be denied that in the

course of his work at Troy, and at other sites mentioned in the Homeric poems, notably Mycenae

and Tiryns, he completely altered the study of the pre-Classical Aegean world.

The site of Hisarlık was known in Classical times as Ilion, a name used in Homer as an alter-

nate for Troy. Through the Roman period it was only a small town, but Greeks and Romans

venerated it as the site of Homeric Troy. Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar both paid their

ALBANIA

MACEDONIA

GREECE

Mycenae

Troy

BULGARIA

Miletus

Kition

CYPRUS

JORDAN

SYRIA

Tarsus

Hattusa

(Bogazköy)

Kanesh

(Kültepe)

TURKEY

(ANATOLIA)

Pylos

MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Approximate Political Boundaries

of Hittite Empire

LIBYA

0 200 400 km

EGYPT

CRETE

Nile

Troodos Mts

Enkomi

Uluburun

Cape Gelidonya

AEGEAN SEA

BLACK SEA

Ugarit

Qadesh

LEBANON

PALESTINE

ISRAEL

Athens

Figure 8.1 Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean in the Late Bronze Age

140 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

respects here to the long vanished heroes. After antiquity, the site was abandoned and by the

nineteenth century had lost all association with the events recorded in Homer. Consequently,

even for those who believed in the reality of the war, the plain in which Troy sits offered other

appealing candidates for the site of the famous citadel.

Schliemann believed Hisarlık the best candidate. He was not, however, the first to dig at this

site. That distinction belongs to Frank Calvert, an Englishman who served as the American

consul in the nearby city of Çanakkale, and who first directed Schliemann’s attention to Hisarlık.

But Schliemann’s campaigns, on a large scale hitherto unmatched and with precise intellectual

aims, captured the attention of the educated world at large. Schliemann at first had no idea of the

significance of his finds. But he was a pioneer, with precious little to guide him; before he began

at Troy, the sequence and dating of cultures in the Aegean Bronze Age were poorly understood.

Great advances were made in the following decades, but Schliemann’s life drew to a close before

he could fully assimilate these new findings. It would fall to Wilhelm Dörpfeld, the young archi-

tect Schliemann had taken on as an assistant, to clarify, in the 1890s, the sequence at Troy, with

further modification in the 1930s by Carl Blegen and a team from the University of Cincinnati.

Since 1988, a joint project of the Universities of Tübingen and Cincinnati has continued to refine

our knowledge of the site.

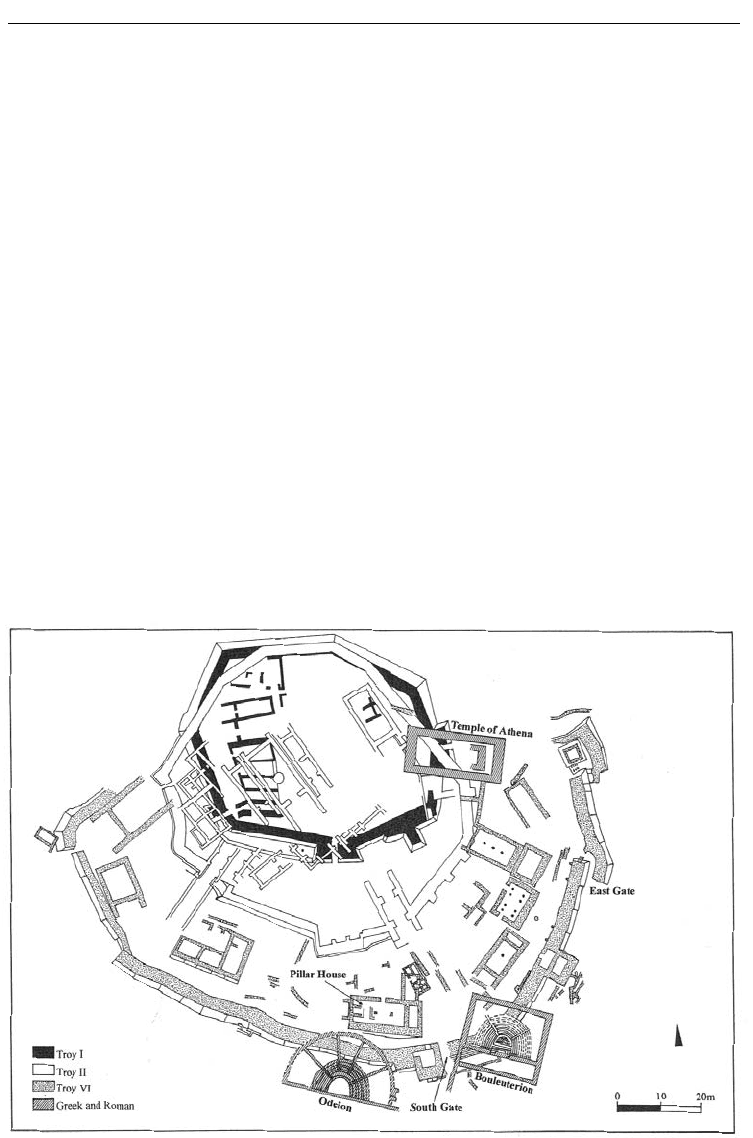

Troy is a höyük, that is, an artificial mound consisting of the remains of successive layers of

human habitation, very much like other such mounds in the Aegean, Anatolia, and the Near

East. Built at the end of a natural ridge that projects from east to west into the plain of the Sca-

mander River, just south of the Dardanelles, the mound developed in the standard manner with,

in general, each succeeding town built on top of the preceding one and enlarging its boundaries,

spilling out beyond the confines of the earlier settlement (Figure 8.2). Today’s visitor does not

Figure 8.2 Plan, the Citadel, Troy: major buildings

ANATOLIAN BRONZE AGE CITIES 141

see this clearly, because the construction in the Greek period of a Temple to Athena sheared off

the top of the mound. Moreover, extensive modern excavations have also removed much. What

one sees, then, is a series of concentric circles, the remains of the lowest sections of each level.

Schliemann and Dörpfeld divided the many habitation levels into nine major periods; sub-

sequent research has split these into numerous phases. These “nine cities” of Troy range in

date from the Early Bronze Age (Troy I) through the Greek (Troy VIII) and Roman (Troy IX)

periods. Which level corresponds to the Troy of Priam and Homer is still a subject of debate

(see below).

The current excavations, begun in 1988, have contributed important new information about

the site. The previously excavated mound has been demonstrated to be only the small (2ha) for-

tified citadel of a larger town. Exploration south of the citadel has revealed the existence of an

enclosed lower city of Troy VI and VII, 18ha in area, underlying the much later Roman town. The

combination of citadel and lower city is familiar from such Aegean sites as Tiryns. Middle and

Late Bronze Age Troy has now become a respectably sized town, comparable to other Aegean

centers, and as such a credible opponent of Mycenae and its allies. But Troy also had Anatolian

connections. The fortification wall is of Anatolian-Near Eastern type, with foundations consist-

ing of stone-walled compartments filled with earth. Such “casemate” walls have been discovered

also at LBA Miletus, further south on the Aegean coast, and at Hattusa, the Hittite capital.

What was the nature of the site? It would seem that the walled citadel contained houses and

meeting places for rulers and some of their subjects, and offered refuge in times of trouble. The

lower city of Troy VI and VII contained more extensive habitation. Beyond the walls would be

farmhouses and such connected areas as cemeteries, but this is still poorly known. For a sample

of the remains of Troy, let us look at three levels of particular interest: Troy II, with its fortifica-

tions and megarons; Troy VI, with its walls, gates, and representative houses; and Troy VIIa,

with its possible preparations for a siege.

Troy II

Troy II is the major level of the Early Bronze Age. The walls enclose a roughly circular area some

110m in diameter. Like those of the preceding Troy I, these walls were built of stone foundations

with a sun-dried mud brick superstructure. The foundations alone survive, 2m high, made of

small, unworked stones. Their exterior surface is battered, that is, sloping, a distinctive character-

istic of the walls of Troy in all periods. Towers stood at intervals of 10m. Today, the visitor can

admire in particular the south-west gate (Figure 8.3). A long steep ramp leads up to the gateway,

laid out on a three-part plan, outer and inner gates with a central room in between. Such a plan

allows for a better control of those coming in or out.

The main buildings inside Troy II are called megarons, after Homer – here, simple long rect-

angular structures, with a front porch and a larger rectangular room behind. In contrast with later

Mycenaean megarons, the Troy II examples are freestanding, not embedded inside a larger palace

complex. They stand parallel to each other, aligned on a north-east to south-west axis. The largest

has been labeled Megaron II A. Although much of its western side was destroyed by Schliemann

before he realized what he was digging through, its measurements can be reconstructed as roughly

30m × 10m. Its walls consisted of sun-dried bricks, reinforced by wooden beams, erected on

foundation of large unworked stones. Remains of a circular clay platform, the ancestor of the

hearth in the Mycenaean megaron, were discovered in the middle of the beaten clay floor. The

building is sufficiently wide that a central row of columns must have supported the flat roof of clay

and reeds laid on beams. Presumably the columns were of wood, but all traces have vanished. As