Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

122 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

and cult center. In general, what survives is the basement floor, and many of the above activi-

ties are attested in the small basement rooms. The appearance and purpose of the now largely

vanished upper stories are uncertain. Nevertheless, some evidence survives to suggest the recon-

struction of these sections. In the south-east, the “Residential Quarters,” the Grand Staircase

connected at least four superposed levels. Periodic indentations in the west facade of the palace,

thickened ground floor walls, fallen debris (such as shattered wall paintings), and large columns

bases found in situ on upper floors suggest that large public rooms lay upstairs, covering a cluster

of basement rooms. So the original appearance of the palace, and the overall balance of larger

and smaller rooms, would have been quite different from what one can visualize today.

The palace at Knossos is linked by its complicated plan with a striking legend of the later

Greeks, that of King Minos, the Minotaur, and the labyrinth. According to the legend, Pasiphae,

Minos’s wife, was struck with a passion for a bull. She had Daedalus, the master craftsman,

construct a model of a cow for her to climb inside. So skillful was the model that the bull was

fooled. In due course Pasiphae gave birth to a monstrous creature, half man, half bull, called the

Minotaur. The unfortunate Minotaur was banished to a specially built complex, again designed

by Daedalus, a maze-like warren of rooms called the Labyrinth. There the monster consumed an

annual tribute of fourteen Athenian youths, male and female, until at last he was slain by Theseus,

with the assistance of Minos’s daughter, Ariadne.

Although no evidence from the Bronze Age attests to the existence of Minos or his family, the

remains of the “Palace of Minos,” as Evans called it, do conjure up the legend of the labyrinth.

The plan shows a profusion of small rooms, and at first glance it makes little sense. But Minoan

architecture has its own logic. Indeed, the general similarities between the palaces and other

sites indicate that labyrinthine layout was not a specifically Knossian feature, but a general trait,

and that these ground plans were deliberate. J. W. Graham, a specialist on Minoan architecture,

even claimed that a Minoan foot measured 0.3036m, slightly smaller than the English foot, and

proposed that the indented west blocks of the palace at Phaistos, at least, were laid out in even

numbers of Minoan feet.

If we approach the palace at Knossos from the north-west, coming in along the paved Minoan

street known today as the Royal Road, we reach first a low complex of two flights of shallow steps

that meet at a right angle, one leading eastwards toward the north entrance to the palace, another

leading south toward the flagstone-paved west court and the west entrance. Evans labeled these

steps the Theatral Area, imagining ritual dances taking place in the small paved area at the base of

the steps. Probably they served simply to direct people toward the two entrances of the palace. The

palace entrances are both modest, especially considering the size of the palace. They lead into nar-

row corridors, not grand halls, providing access to the central court or to stairs to the upper floor.

From the north entrance one passes through one side of a pillared hall which supported a dining

room above. The discovery of many cooking pots just to the east suggests a kitchen in the area.

The rectangular central court is a standard feature in all Minoan palaces. At Knossos it mea-

sures ca. 50m × 25m, somewhat larger than the courts elsewhere. Oriented north–south, the axis

of the court points toward the notched peak of Mt. Juktas, the prominent landscape feature to

the south. Minoans revered mountain peaks; they established shrines near summits and some-

times, as here, deliberately oriented their major buildings toward them. In addition to providing

access to most sections of the palace, the central court may have been the location for bull sports.

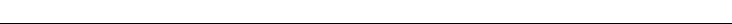

Several representations of a sport between men (or boys), women (or girls), and bulls survive

from Minoan art, among them the Fresco of the Bull Leapers (also known as the Taureador

Fresco), a wall painting from the Court of the Stone Spout in the north-east sector of the palace

(Figure 7.3). The evidence such images present is somewhat confusing, but it seems the sport

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 123

involved vaulting over a bull, either by grabbing its horns or by doing a handspring on its back.

The risk of getting gored was great, as some depictions show. In what context these sports were

performed, whether religious or secular, we do not know.

The basement rooms along the west side of the central court were devoted to cult. The Throne

Room, so-called by Evans on the basis of the armless stone chair with the back cut out in a flame

pattern that was found against its north wall, was in reality a cult room. This small complex con-

sisted of the chair; stone benches along the walls; wall paintings of griffins, imaginary creatures

with a lion’s body and an eagle’s head that served as magical protective beings; and, adjacent to

the main room, a so-called lustral basin, a gypsum-lined space sunk below the floor of the main

room and accessible by two flights of steps. Another common feature in Minoan palaces and vil-

las, lustral basins could be used as bathrooms (Minoans eventually took up bathing in clay tubs) or

as places for ritual anointings or ablutions. To the south of the Throne Room, beyond the broad

staircase that leads to the upper floor, lie a Triple Shrine façade and storerooms for cult objects,

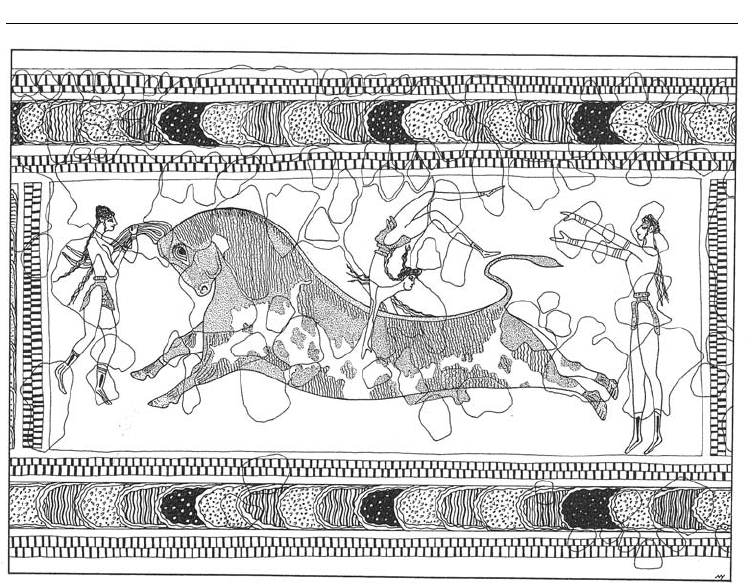

including two stone-lined pits sunk in the floor, the Temple Repositories. In these were discovered

statuettes of women in typical Minoan multi-layered flounced skirts and tight short-sleeved jackets

that exposed the breasts, with snakes wound around their arms (Figure 7.4). These figurines may

represent the goddess who seems to stand at the head of the deities worshipped by the Minoans, or

these women might be priestesses. The material is faience, a substance related to glass.

To the west of the cult rooms one finds a series of storerooms, narrow rooms that give onto

a north–south corridor. The rooms contained pithoi (large clay jars) and boxes, lined variously

with gypsum, plaster, or lead, sunk into the floor. The pithoi were used for the storage of olive oil,

grain, and lentils, important crops in the subsistence-based (or agricultural) economy of the Mino-

Figure 7.3 Fresco of the Bull Leapers, partly restored, from Knossos. Herakleion Museum

124 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

ans; the lined boxes could hold valuables as well as food

products. Important information about the economy

of Knossos during the later Post-Palatial period comes

from the clay tablets inscribed in the Linear B script. But

these tablets are associated with the Mycenaean occu-

pation of the palace; how accurately they reflect earlier

Minoan-controlled economic activity is unclear.

The north-east sector of the palace, badly ruined,

was the center for craft workshops, such as the pro-

duction of stone vases. The south-east sector con-

tained the Residential Quarters. Thanks to Evans’s

reconstructions, these rooms can be well appreciated

by visitors. The hill slopes down toward the east, as in

fact it does toward the south and west, but on this side

the builders of the palace took advantage of the slope

and cut down two fl oors worth from the level of the

central court. A Grand Staircase leads down, lined with

red columns, oval in cross-section, that taper down-

wards, and round black column capitals (the red and

black colors have been restored, based on the evidence

of wall paintings). The main rooms on the lowest fl oor

were named by Evans the Queen’s Megaron and the

Hall of the Double Axes. Both illustrate key features

of Minoan domestic architecture.

The Queen’s Hall, as it is better called to avoid con-

fusion with the megarons of Mycenaean palaces (see

below), consists of a main room with a lustral basin,

or bathroom, off it, on the west side. On the east side, one looks first through a row of piers,

then beyond, through a row of two columns to a

light well, a tiny open-air courtyard enclosed by high

walls. The first row of piers contains niches in their

sides, into which the wooden door flaps could be

folded during the warm months when the circula-

tion of air was desired, or opened across the spaces

between the piers, to close the main room off from

the outside air. This sort of divider that can be con-

verted into a wall from a series of piers, either as a

whole or in part, is called a pier-and-door parti-

tion. The light well provided air and light down to

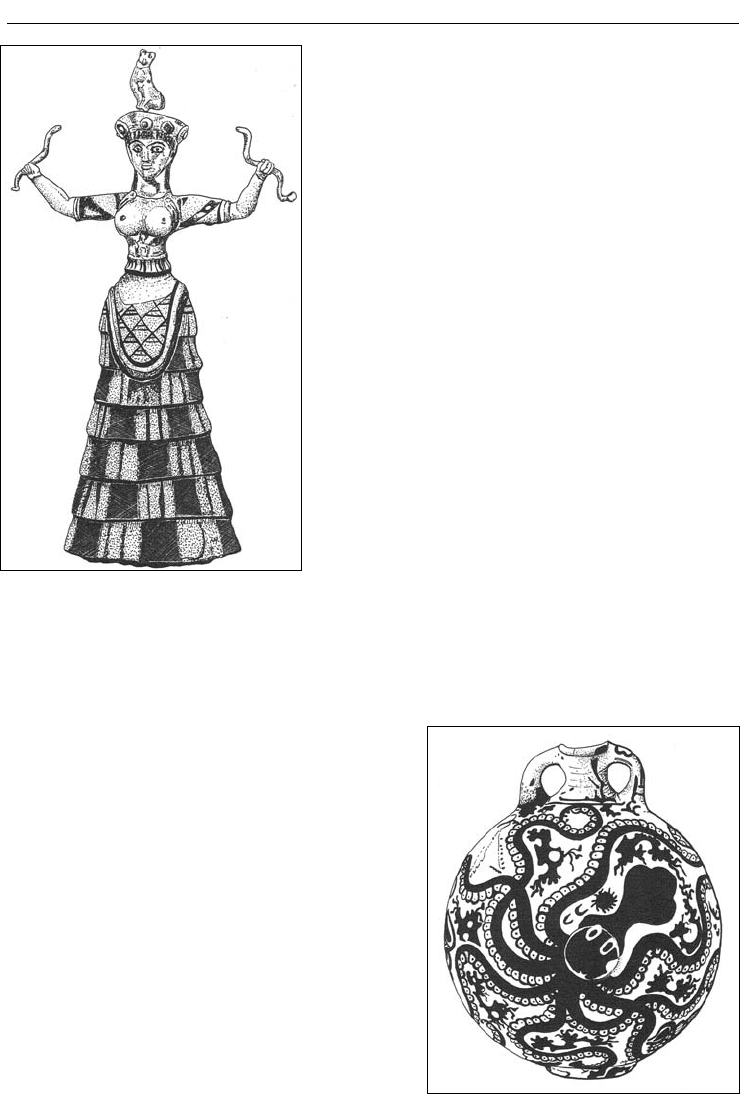

this low level. The Queen’s Hall was decorated with

wall paintings, mostly geometric patterns. A fresco

of dolphins has been installed on the north wall, but

this is not its original location. The fragments of the

painting, found in the adjacent light well, had fallen

from an upper room where they belonged to a deco-

rated floor. The fresco illustrates the Minoan love of

sea creatures as subjects for art (for another example

Figure 7.4 Snake goddess, or priestess;

faience figurine, head and left forearm

restored, from Knossos. Herakleion

Museum

Figure 7.5 Lentoid flask with octopus;

Marine Style, LM IB; from Palaikastro.

Herakleion Museum

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 125

of this theme, see Figure 7.5). Presumably the Queen’s Hall served as a bedroom, but for whom,

despite the regal name given in modern times, is completely unknown. A corridor leads westward

to small rooms, stairways to upper floors, and a toilet, this last linked to the extensive system of

stone-lined drains that ensured sanitation in this part of the palace.

The bigger Hall of the Double Axes has a somewhat different layout. It too has a main room,

paved with gypsum fl agstones, that looks out through pier-and-door partitions across a second

room toward a light well. But here the main room is enclosed on three sides by pier-and-door

partitions, and the second room is just as large as the fi rst. In addition, in the direction opposite the

light well, the main room gives onto a colonnade and a terrace, with a private and soothing view,

we might imagine, to a garden or grove of trees, the stream below, and the ridge beyond. The Hall

takes its name from the symbol carved on its walls. The double axe seems to have had mystical

importance for the Minoans. Why there should be so many carved in this room, whether private

apartment or public audience hall, is a mystery.

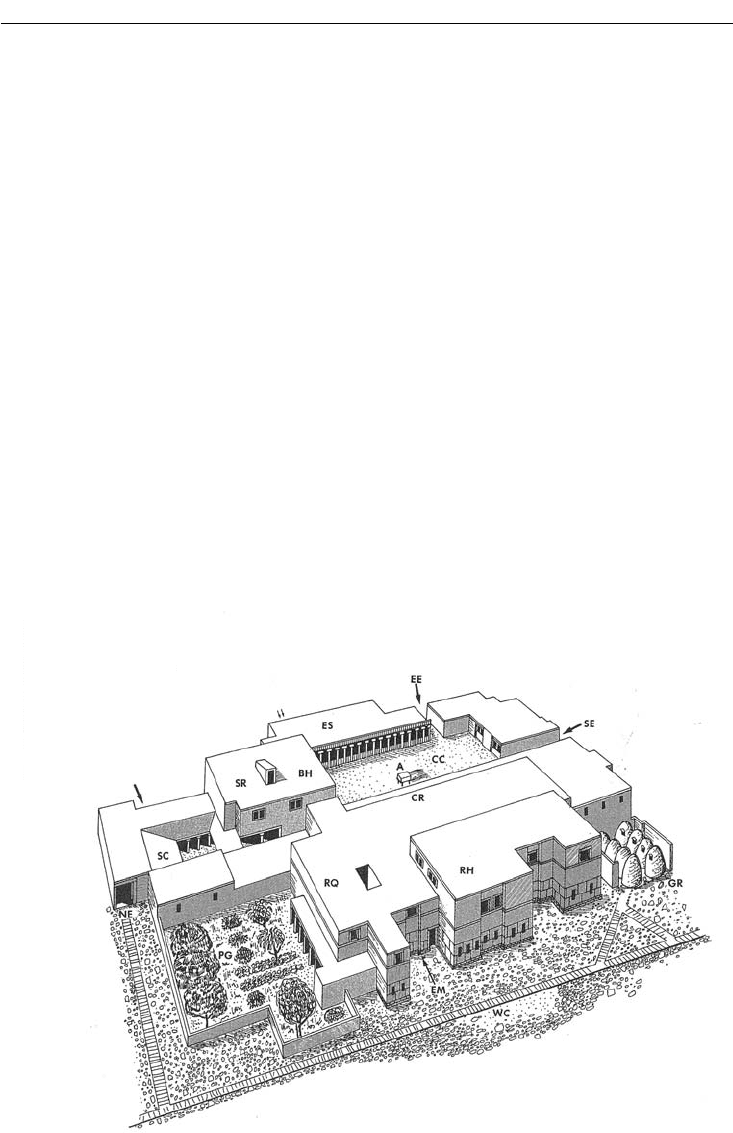

The other palaces known so far show similar features in function and plan. So, too, on a

smaller scale, do the “villas” or mansions, found both in the Knossos area and in the countryside.

But variations occur as well, especially in siting, dimensions, and decoration. For a comparison

with Knossos, the palace at Mallia offers a good contrast (Figure 7.6).

Minoan towns: Knossos and Gournia

Although the palaces dominate any consideration of Minoan architecture, we must not forget

that they were only the cores of larger towns. At Knossos, a region of 10km

2

(1000ha) around

Figure 7.6 Palace of Mallia from the north-west (reconstruction)

A Altar in Central Court

BH Banquet Hall

CC Central Court

CR Cult Rooms

EE East Entrance

EM Entrance in the West Magazines

ES East Storerooms

GR Granaries

NE North (Service) Entrance

PG Palace Garden

RH Reception Halls

RQ Residential Quarter

SC Service Court

SE South (Main) Entrance

SR Stairway to Roof

WC West Court

126 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

the palace has been explored over many

decades by the British School of Archae-

ology at Athens. In the course of exca-

vations and surface surveys, buildings,

tombs, roads, and other features of Neo-

lithic, Bronze Age, and Classical antiquity

have been recorded on the overall urban

plan. The coastal settlement at Amnisos

apparently served Knossos as its port.

Sinclair Hood, an expert on this region,

has estimated that the palace and city of

Knossos during the New Palace period

occupied 75ha, with 12,000 inhabitants.

Greater Knossos, an area estimated at

20km

2

, comprising the city and its imme-

diate hinterland including the harbor, may

have contained 15–20,000 persons. Colin

Renfrew, another specialist, has estimated

4–5,000 in the palace, 50,000 in the entire

territory controlled by Knossos.

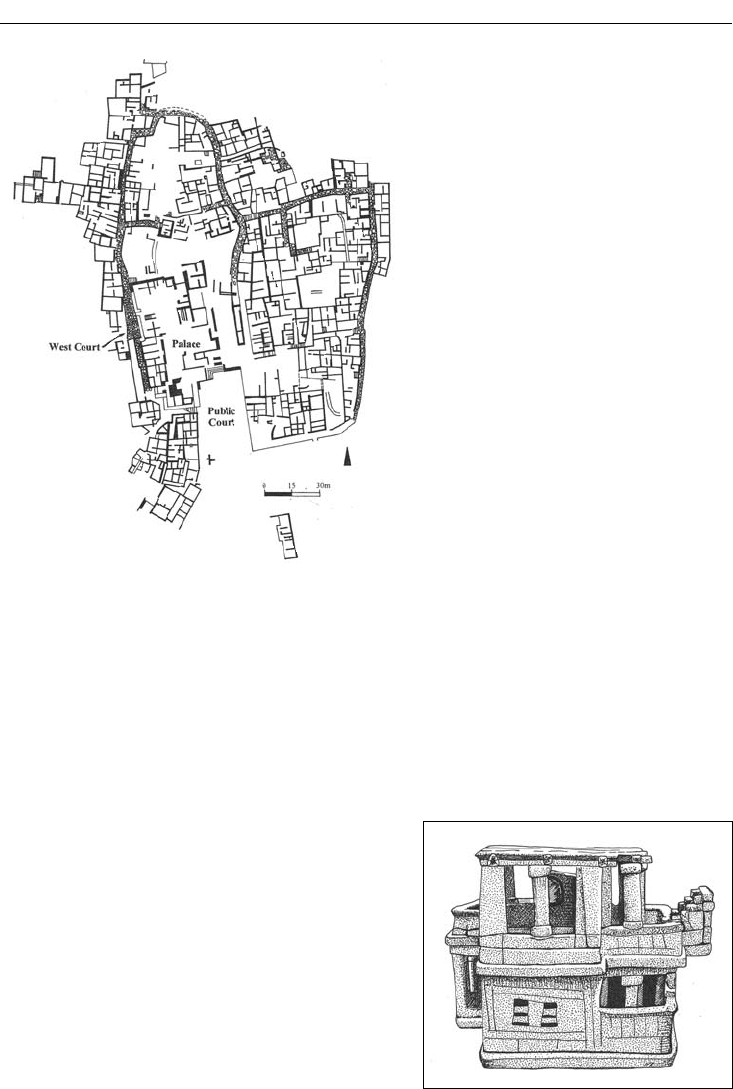

The only Neopalatial Minoan town

excavated in its entirety is Gournia. This

small settlement on a hill by the sea in east-

ern Crete was excavated by the American

Harriet Boyd Hawes in the fi rst decade of this century. Barred from the then men-only excava-

tions, she decided to undertake her own project, and set off on donkey-back for eastern Crete with

fellow archaeologist Edith Hall. Gournia has a palace-like building that sits at the summit of the

hill and dominates the settlement. The slopes of the hill are covered with blocks of small houses

divided by meandering paved streets (Figure 7.7). Houses were often two-storied, with rooms for

animals and storage on the ground fl oor, and living quarters for the owners on the upper fl oor.

A stairwell led up through the center of the house. Where it emerged on the fl at roof, or onto a

terrace covered with light materials (a thatch awning,

for example), it was protected by a built cover. This

and other features can be seen in a series of small

faience plaques from Knossos known as the Town

Mosaic, and in the remarkable clay model of a house

discovered at Arkhanes (Figure 7.8).

The plan of Gournia, with a main building domi-

nating a village of small houses, is but one type of

town layout seen in Neopalatial Crete. Other config-

urations include a central palace surrounded by large

houses, or villas (e.g. Knossos); house blocks aligned

along cobbled streets, without a dominating palace

or villas (Palaikastro); a cluster of villas (Tylissos);

and solitary villas off in the countryside, the centers

of agricultural estates (Vathypetro).

Figure 7.7 Town plan, Gournia

Figure 7.8 House model, terracotta; MM

IIIA; from Arkhanes. Herakleion Museum

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 127

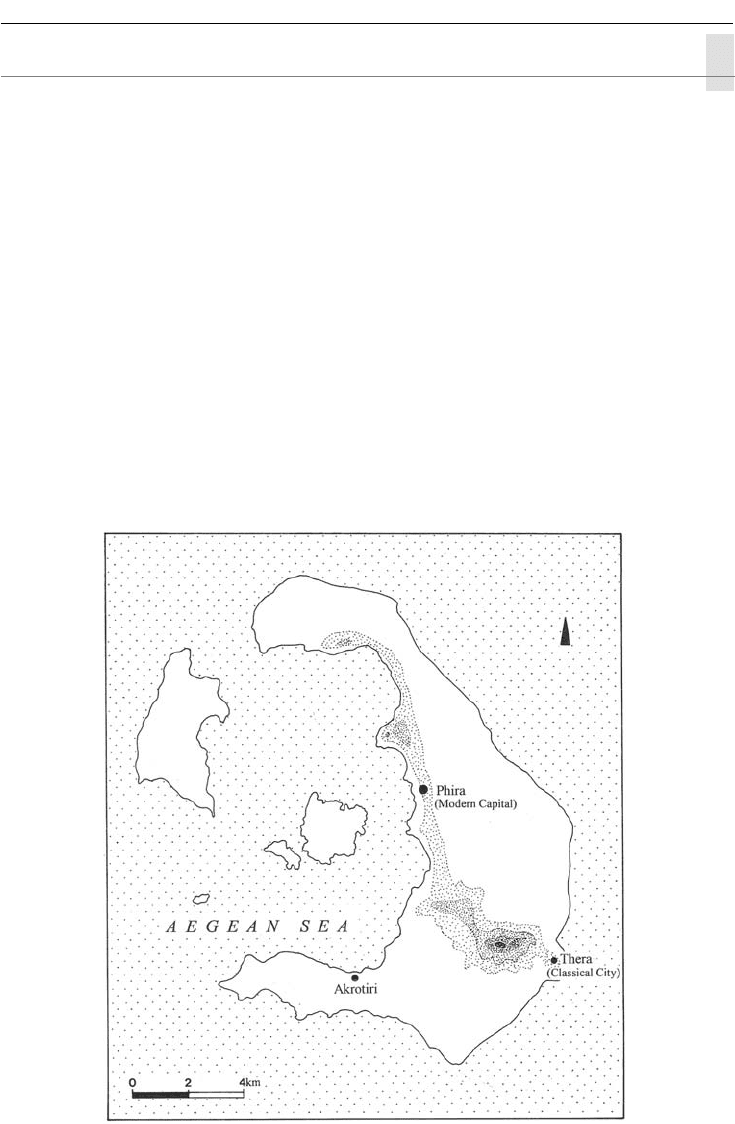

THERA: AKROTIRI

Thera, or Santorini (its medieval name), is a cluster of islets in the southern Aegean that once

formed part of a single irregularly shaped volcanic island. When the volcano erupted in the mid-

second millennium BC, the center collapsed into the sea, leaving only the broken rim above water

– the islands we see today (Figure 7.9). Volcanic activity since the Bronze Age has produced a

new island in the center of the caldera, and from this fumes continue to spew forth.

In 1967, spectacular results from the new excavations at Akrotiri on the southern end of the

main island of Thera focused attention on the Bronze Age explosion and its effect throughout

the Aegean region. Spyridon Marinatos, the Greek excavator of Akrotiri, had long believed that

the explosion of Thera caused or triggered the widespread destructions at the end of the New

Palace period on Minoan Crete, ca. 1450 BC. This theory seemed to receive confirmation at

Akrotiri: an entire town buried in volcanic pumice and ash. But the pottery found at Akrotiri is

contemporary with an earlier phase on Crete, LM IA, and so the date of the explosion has now

often been placed ca. 1520 BC. This date is, however, highly controversial. Arguments based on

scientific evidence, such as ice-cores from Greenland and growth patterns in tree rings from Ire-

land, and on new interpretations of correlations of archaeological materials between the Aegean

and the Levant and Egypt, have led some to champion an even earlier date, ca. 1628 BC. At least

Figure 7.9 Thera (Santorini)

128 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

it is now clear that whatever its effects on Crete, the eruption had no direct influence on the end

of the New Palace period.

Only a small portion of Akrotiri had been uncovered by 1974 when the accidental death of

Marinatos brought the excavations to a halt. Nevertheless, one gets a good impression of the

ancient town. Houses are preserved up to the third story. Sometimes they stand alone, but often

they are grouped in clusters. Doorways, windows, stairs, sewage drains, and the walls of mud

brick and irregular stones with wooden branches and beams added for reinforcement can be

seen. Streets are not straight and even, but turn, widen, and narrow with irregularity. Sometimes

small squares are formed (Figure 7.10). The architecture resembles that of Minoan Crete, but

differs in detail, both in form and in construction techniques. The Therans liked pier-and-door

partitions, for example, but rarely used light wells. The north facade of one building, Xeste 4,

shows an interesting technique of stone masonry, one not seen on Crete: its ashlar courses get

progressively smaller from top to bottom.

Figure 7.10 West House, Akrotiri, Thera

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 129

Although Akrotiri has been called a Bronze Age Pompeii, after the Roman town buried in

the eruption of the volcano Vesuvius (see Chapter 21), it differs from Pompeii in one important

respect. The inhabitants of Akrotiri were aware of impending disaster, perhaps through earth trem-

ors or fumes, and so escaped, taking their precious belongings with them. Objects left in the houses

included pottery and cooking equipment, as well as furniture such as beds, and stone tools and

vases, but virtually no metal or other truly valuable luxury items. The many wall paintings, however,

they could not remove. These frescoes were in general well preserved, indeed far better than any

other from the Bronze Age Aegean, although they often survived only as plaster fragments heaped

at the bases of the walls. Restoring and reassembling the pieces has been a painstaking task.

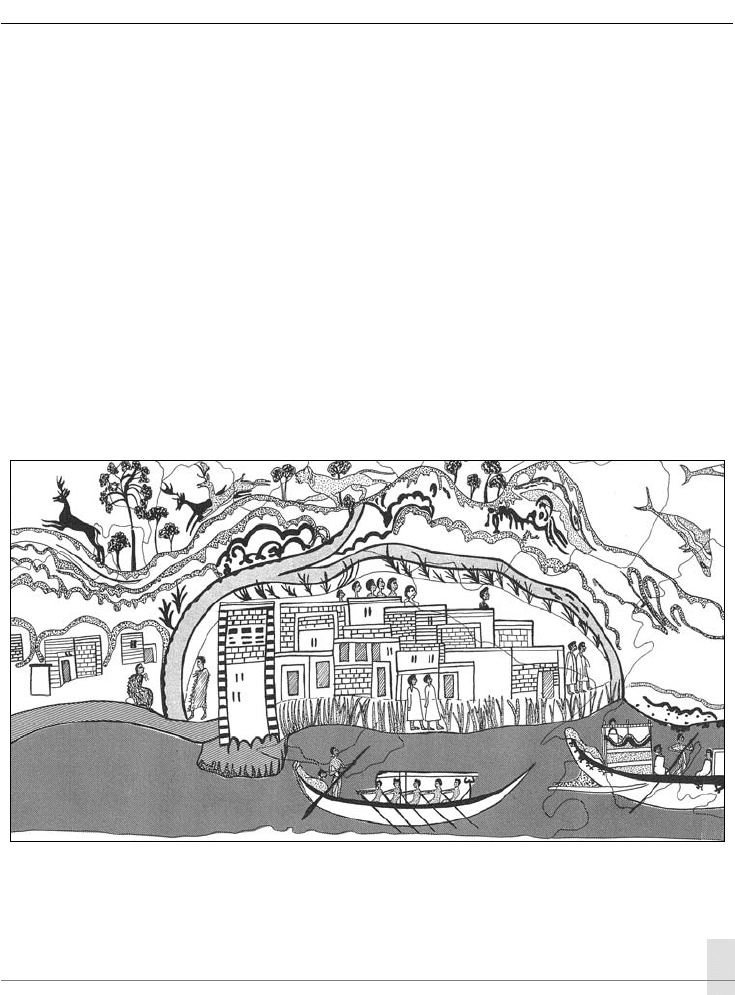

The most important of the paintings is a long strip 40cm high that shows a group of elegant

boats making their way between two towns (Figure 7.11). This miniature wall painting comes

from Room 5 on the upper floor of the West House, where it was part of a larger program of

wall decorations showing people in five towns and a variety of landscapes. The precise subject is

much debated: which towns, and which occasion? Lyvia Morgan, in a comprehensive analysis of

the painting, favors a nautical procession, a festival celebrating the resumption of the navigation

season in late spring, from a minor Theran town to the important center of Akrotiri itself.

THE MYCENAEANS: MYCENAE AND PYLOS

The Mycenaeans held sway in central and southern Greece during the Late Helladic period (the

term used to denote the Late Bronze Age on the Greek mainland), from ca. 1650–1050 BC. Their

culture jelled in two regions, in Messenia in south-west Greece, and in the home region of Myce-

nae, the Argolid, the area dominated in Classical Greek times by the city of Argos. From the fif-

teenth century

BC on they expanded their holdings across the Aegean to the Anatolian shore, taking

over the territories once controlled by the Minoans. They developed extensive contacts not only

with the established civilizations of Egypt and the Levant but also with Europe and the lands of the

Figure 7.11 Ship Fresco (detail); South wall, West House; Akrotiri, Thera

130 THE NEAR EAST AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

western Mediterranean. At some point they fought the Trojans of north-west Anatolia, if we accept

that some kernel of truth lay behind the later Greek legends of the Trojan War. Economic conflicts

may have sparked the war, perhaps a dispute over access to the rich lands of the Black Sea.

The Mycenaeans were speakers of the earliest known form of Greek. They wrote in the Linear

B script, a syllabary derived from the Minoan Linear A. It is not known when the Greek language

originated or where, whether inside Greece or brought from elsewhere, but its development has

been connected with the movements of peoples speaking other Indo-European languages of

which Hittite was another early example (see Chapter 8). The archaeological record shows major

changes in material culture during the final phases of the Early Bronze Age, ca. 2300–2000 BC,

but after that, a smooth development through the Middle Helladic into the Mycenaean period.

We might postulate, as many have, major immigrations of people from Anatolia and south-east

Europe into Greece toward the end of the Early Bronze Age, with a continuing trickle after-

wards, and gradual fusion of the newcomers’ language with those of the locals into what we

know as Mycenaean Greek. But this is only a hypothesis. Movements of language groups cannot

always be traced in distribution of pottery or other objects, and conversely, a change in material

culture need not indicate a change in ethnic group.

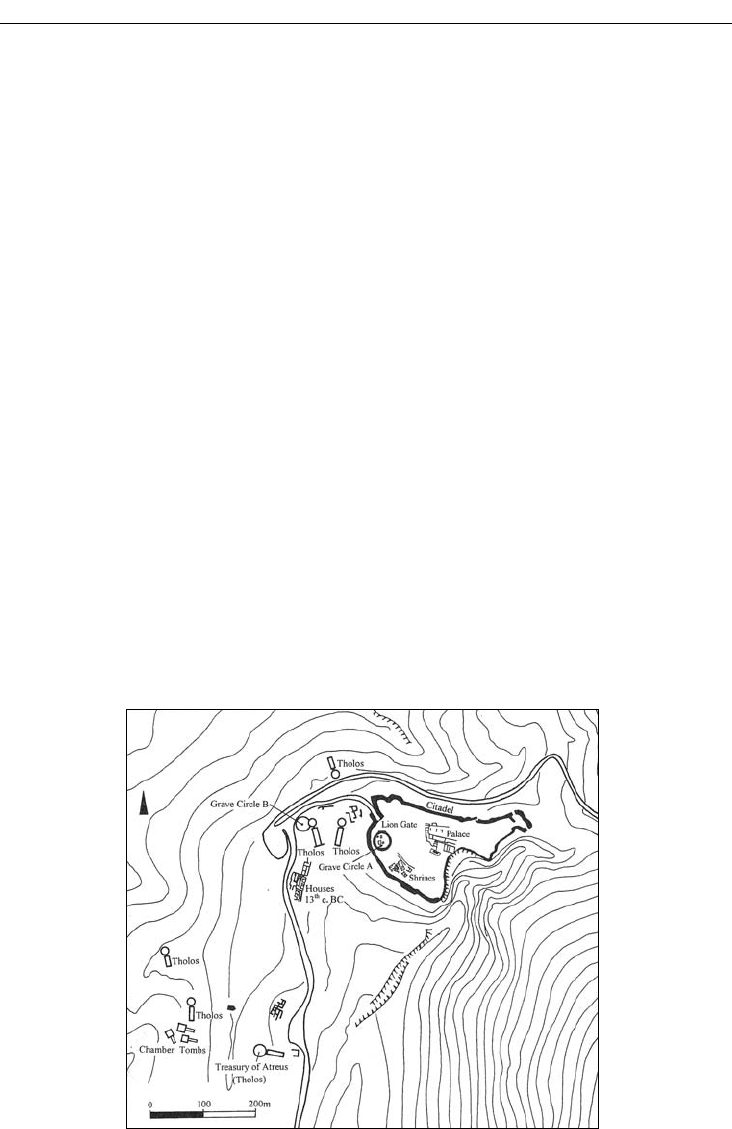

Mycenae

Mycenae, the city that has given its name to the culture, lies 15km from the sea at the north end of

the Argive Plain. Its citadel sits on a prominent hilltop, itself in the protective crook of two larger

hills. The site was first explored in 1876 by Heinrich Schliemann, the great pioneer of Aegean pre-

history, and has been excavated to the present day by a succession of Greek and British archae-

ologists (Figure 7.12). As an urban entity, Mycenae seems disconcertingly fragmented. Because

of erosion and the building activities of post-Bronze Age inhabitants, remains of the Late Bronze

Figure 7.12 Overall site plan, Mycenae: the Late Bronze Age

AEGEAN BRONZE AGE TOWNS AND CITIES 131

Age town have been erratically preserved. Its 600 years of history have to be assembled from bits

and pieces – some of which are quite spectacular.

The Shaft Graves of Mycenae

The first dramatic evidence of the Mycenaeans comes from Mycenae itself: the Shaft Graves,

with their fabulous gold treasure. The Shaft Graves occur in two clusters. The earliest group, dat-

ing to ca. 1650–1550 BC, lies outside the thirteenth century BC citadel, near the modern parking

lot. It was surrounded by a low circular wall. Because this cluster was the second to be discov-

ered, in 1951–52, it is known as Grave Circle B.

The later group, ca. 1600–1500 BC, in part contemporaneous with the burials of Circle B, in

part later, was discovered by Schliemann in 1876 and Panayiotis Stamatakis in 1877 just inside the

entrance to the citadel. These graves were also surrounded by a circular wall. But this wall was built

some 250 years later, part of the rebuilding of the citadel in the thirteenth century BC. Although

this later group of Shaft Graves is conveniently known as Grave Circle A, there is no convincing

evidence for the existence of a circular wall around them at the time the graves were dug.

A shaft grave is a stone-lined rectangular trench placed at the bottom of a shaft dug out of the

bedrock or accumulated earth and lined with rubble walls. The deceased was placed on a floor

of pebbles; objects were left in the tomb with the body; the trench was covered with a roof of

thin stone slabs supported on wooden beams; and the remaining shaft was then filled with earth.

After the funerary meal, the debris, bones and crockery, were thrown into the shaft. Earth was

mounded over the top, and in many cases, a stele, or thin stone slab, sometimes carved, was

planted upright in the earth as a grave marker. When the tomb was reused, as was often the case,

the shaft had to be cleared and the roof of the tomb removed. This proved cumbersome, and

may explain why the shaft grave type fell out of use by the fifteenth century BC.

Circle B contained fourteen true shaft graves and one later tomb built of masonry. Twenty-

four persons were buried here. In Circle A, six Shaft Graves were found, as well as remains of

other miscellaneous burials. Nineteen persons were buried in the six shaft graves, eight men,

nine women, and two children. The grave goods in these tombs were far more lavish than in

the burials of Circle B. Now on display in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens,

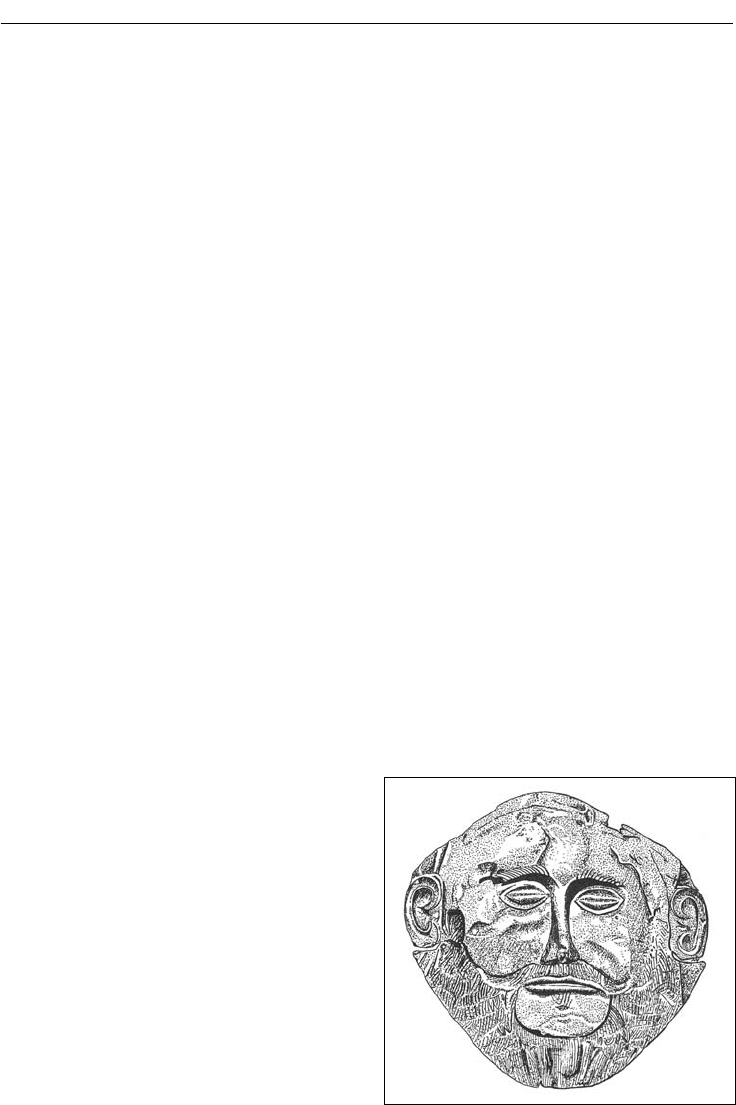

they include gold funeral masks (Figure 7.13);

gold jewelry; bronze daggers inlaid with hunt-

ing scenes depicted in gold, silver, and niello,

a black metallic compound; a silver rhyton, or

ceremonial drinking cup with a pointed bot-

tom, with the siege of a fortress depicted on it

in repoussé (the technique of making an image

in relief by delicately hammering the metal

sheet from the back); and vessels of pottery,

stone, and precious metals. Minoan influence is

strong. The Mycenaeans had not yet conquered

Crete but, although just emerging from the

rustic doldrums of the Middle Helladic period,

they already recognized the Minoans as the

providers of the finest in design and craftsman-

ship. Minoan style would continue to exert a

great attraction for Mycenaean artists long after

Figure 7.13 Gold funeral mask; Shaft Grave

V, Grave Circle A; Mycenae. National

Archaeological Museum, Athens