Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

VINCE GARDINER

16

and Folkestone and Dover Water Services Ltd with French companies. At the time of writing,

Wessex Water is the subject of a take-over bid from the American utility company, Enron.

Indeed, water privatisation has been seen as part of an inevitable global privatisation process

by transnational companies and corporations

Undoubtedly, there has been a change in ethos in the water industry within the last

decade, from that of a public service to that of a provider of a consumer need. This has been

harshly underlined by the debate on disconnections of domestic supplies of those most

disadvantaged in society who have been unable to pay for water, and by the enforced use of

pre-payment meters. There have been many contentious and sometimes very controversial

issues raised, and these are discussed below. However a crucial element in understanding

these issues is the existence of regulatory bodies in the new structure of the water industry.

These will therefore be described before addressing the controversial issues.

Regulation in the water industry

OFWAT (the Office of Water Services) is a non-ministerial central government agency

employing (in 1997/8) 206 staff, and with running costs of £9.9 million per year, plus

another £2.2 million for its consumer committees. Its head, the the Director-General of

Water Services, is the economic regulator of the water and sewerage industry in England

and Wales. His (the current Director-General is a man) primary duties are to ensure that

the companies carry out their functions in accord with legislation, and that they are able

to finance their functions. His secondary duties are to ensure that no undue preferences or

discriminations are shown in charging—for example between urban and rural areas, large

and small consumers, metered or unmetered consumers—and that customers’ interests

are protected. In some senses, he acts to even out geographical differences. However, the

Director-General has called for his responsibility to protect the interests of customers to

be made his single primary duty, putting customers’ interests at the heart of water

regulation. The Director-General has a duty to promote efficiency of water use, to facilitate

competition in the industry, and a general environmental responsibility. He does not set

environmental standards, but works closely with the Environment Agency (which is

responsible for protecting the quality of rivers, estuaries and coastal waters) and the

Drinking Water Inspectorate (which oversees the quality of tap water) (see pp. 18–21).

He carries out his regulatory duties largely by means of setting price caps which allow the

companies to finance their functions; he does not control profits or dividends directly.

The current price limits were set in 1994, and will be reset in 1999. He also compares the

performance of the companies, which helps the poor performers to rise to the standards

of the best, and by setting targets, for example for leakage reduction. There are also ten

Regional Customer Service Committees, and a National Customer Council. Strong and

effective arrangements for the independent representation of the interests of customers

are seen as vitally important in the regulation of a monopoly utility, where customers cannot

take their custom elsewhere.

The ten regional Customer Service Committees of OFWAT have a statutory duty to

investigate complaints made by customers. These can concern water quality, pressure, supply,

sewerage, billing, charges and administration. Complaints about the industry have declined

annually since 1992/3, although showing an upturn in 1997/8. There is some indication that

the temporal, and perhaps spatial, distribution of complaints accords with media coverage

WATER RESOURCES

17

of the industry, and changes in public confidence in and awareness of the complaints

procedure. The proportion of complaints received in each category varies markedly with

region. Of the ten combined water and sewerage companies, South West Water receives by

far the highest rate of complaints per connection, many of which are about billing, charges

or administration. Mid Kent receives a greater proportion of complaints than any other water-

only company.

The Environment Agency is a non-departmental public body established by the

Environment Act 1995. It is sponsored by the Department of the Environment, Transport

and the Regions, with policy links to the Welsh Office and the Ministry of Agriculture,

Fisheries and Food. It took over the functions of its predecessors, the National Rivers

Authority, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Pollution, Waste Regulation Authorities, and parts

of the Department of the Environment. The Environment Agency has the central role in the

planning of water resources at the national and regional levels, and in co-ordinating action

between water undertakings; the industry’s three regulators have the duty of ensuring that it

is carried out properly.

The Drinking Water Inspectorate is responsible for checking that water companies in

England and Wales supply water that is safe to drink and meets the standards set in the UK’s

Water Quality Regulations. Most of these come directly from an obligatory European

Community Directive, but some UK standards are more stringent. Most standards are based

on World Health Organisation guidelines, and generally include wide safety margins. There

are standards for bacteria, chemicals such as nitrates and pesticides, metals, and the

appearance and taste of water.

A tension necessarily exists between the need for regulation to ensure the safeguarding

of the public and the environment, and the need for the water companies to be able to act

freely within the market in terms of pricing and the adoption of technological innovation. It

has been argued (see for example the debate in Economic Affairs, 1998) that there is a need

for further deregulation of the industry, that price controls and rate-of-return regulation lead

suppliers to lower the quality of services, that regulation can never be a substitute for

competition, and that the price mechanism is the most effective means of matching supply

to demand in the long term.

As well as there being debate about the need for regulation, public debate, controversy

and undoubtedly sometimes resentment have focused on many other issues, including the

need for integrated long-term planning and resource management; the impact of privatisation

on quality of water in rivers, lakes and streams; the quality of water supplied; the impact of

EC legislation; financial aspects, including the ‘fat cat’ salaries paid to the chairmen of the

privatised water companies, the soaring stock market values of shares in utilities, and the

high cost of water services to consumers; the absence of any real competition in the industry;

and waste through pipe leakages and other inefficiencies. These are considered below.

Long-term planning

Prior to privatisation, strategic and integrated planning of water resources at the national

level was the concern of the Water Resources Board. Its final report, in 1993, envisaged

higher growth in the demand for water, to be met by large-scale responses including, for

example, estuarial storage of water, increased use of river regulation, and inter-basin

transfers of water. It paid relatively little attention to likely environmental impacts. By

VINCE GARDINER

18

comparison, the National River Authority’s report in 1994 (Water: Nature’s Precious

Resource) questioned whether major developments were in fact necessary for the next

thirty years, and placed much more emphasis upon sustainability, the precautionary

principle, and improved management of demand. By 1994 OFWAT was predicting no

significant growth in demand for the next two decades, and suggesting that localised

shortfalls in water could be met by increased sharing of resources and significant reduction

in leakages. This report favoured universal water metering after the abolition of water

rates at the end of the century, in order to contain demand, although the water companies

opposed this strategy because they would have to bear the cost of installing meters. Strategic

planning of water resources is now the responsibility of the Environment Agency, and

their assessment of the long-term sustainability of the UK’s water resource policies is

summarised below.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland strategic water resource issues have been less

critical, if only because these countries are rather better endowed with the basic natural

resource—rainfall. In Scotland from 1974, water services were the responsibility of the

Regional Councils. From 1996 three water authorities were formed in conjunction with

local government reform, and these became responsible for the provision of both water

and sewerage services. Monitoring of all aspects of water services in Scotland is carried

out by the Scottish Water and Sewerage Customers’ Council. The largest water authority

is West of Scotland Water, which serves the areas formerly served by Strathclyde and

Dumfries and Galloway Regional Councils—over 2.25 million people in an area of over

20,000 square kilometres, which includes not only the industrial heartland of Scotland

and major cities, but also extensive rural areas. Supply is largely from surface water, and

includes thirteen natural lochs, 134 impounding reservoirs, and ninety-five stream

abstraction points, springs and boreholes. East of Scotland Water supplies water services

to 1.58 million people in Edinburgh, Lothians, Borders, the Forth Valley, Fife and Kinross,

and parts of Dunbartonshire and North Lanarkshire. This area has a mean annual

precipitation of 111.5 cm and supply comes from 107 surface sources, including reservoirs,

lochs, and rivers, and thirty-two groundwater sources. Water services for the rest of

Scotland, including the Western Isles, Orkney, Highlands, Grampian, Tayside and

Shetlands, are provided by North of Scotland Water.

In Northern Ireland, the Water Service both supplies water and collects and treats

sewage. It supplies on average 150 million gallons per day to approximately 560,000 homes

and 70,000 businesses, including farms, using reservoirs, pumping stations and treatment

plants at 2,600 locations. A considerable amount of money is being spent in Northern Ireland

on improvement projects to upgrade the standards of sewage and water treatment.

Quality of water

The quality of natural waters is covered in Chapter 18 of this book. Since privatisation the

quality of drinking water in England and Wales has been monitored and reported upon by

the Drinking Water Inspectorate (DWI), who carry out an annual assessment of the quality

of drinking water supplied by each water company, and inspections of individual companies.

Millions of tests are carried out each year by the water companies, and the DWI check these

against the legal standards for drinking water embodied in the Water Quality Regulations.

Most of these stem from an obligatory EC Directive, although some UK standards are more

WATER RESOURCES

19

stringent, and most are

based on World Health

Organisation guidelines.

There are standards for

bacteria, chemicals, metals

and the appearance and

taste of water.

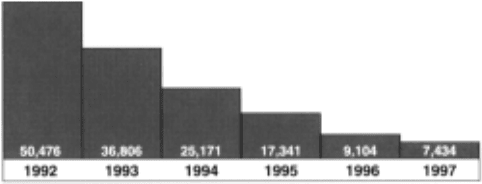

Overall, drinking

water in England and

Wales is of very high

quality, and has been

improving since 1992

(Figure 2.5). In 1997, all

but 0.25 per cent of the

nearly 3 million tests

carried out at treatment works, service reservoirs and in supply zones demonstrated

compliance with the standards set. About 80 per cent of these tests were carried out on

samples taken from consumers’ taps. This improvement, compared with previous years,

reflects the ongoing impact of the enforcement process which has resulted in

improvement programmes. There is no evidence that any of the contraventions found

during these routine compliance tests endangered the health of consumers, as they were

of limited magnitude or duration, or concerned assessment parameters of only aesthetic

significance.

Much concern has been expressed concerning pesticides in drinking water,

originating from their use by farmers, gardeners and highway authorities. The standard

for individual pesticides is very strict, but in recent years there has been a highly significant

improvement in compliance. In 1997, 94.6 per cent of water supply zones met the standard,

compared with 87 per cent in 1996, and 79.2 per cent in 1995. However it must be noted

that if just one sample from a zone fails the test during the year, the zone is treated as

having failed for the whole year. In 1997, 99.96 per cent of the 789,000 tests carried out

for pesticides met the standards, as compared with 99.81 per cent in 1996 and 99.22 per

cent in 1995. This improvement is the result of improvement programmes costing around

£1 billion since 1989.

Overall, for eleven of the seventeen key parameters indicative of water quality, there

were improvements in zone compliance in 1997 compared with the previous year.

Compliance for faecal coliforms was unchanged, and there were small increases in zone

non-compliance for taste and nitrite. However, there were significant increases for coliforms,

colour and trihalomethanes.

The DWI also report upon the extent to which companies conform to monitoring

requirements set by the EC’s Drinking Water Directive. Generally, the companies conform,

although action has been considered against seven companies in 1997 for minor shortfalls

in sample numbers or inappropriate sampling methodology. Each company also met the

Regulations in terms of making the data readily available to the public, although the DWI

are concerned that water consumers make very little use of the public record of drinking

water quality.

FIGURE 2.5 Tests on drinking water which failed to meet standards,

1992–7. In 1997 the water companies carried out nearly 3 million

tests, of which 99.75 per cent passed—a considerable improvement

over 1992

Source: Drinking Water Inspectorate Annual Report, on DWI World

Wide Web pages.

VINCE GARDINER

20

There has been some concern expressed about consistency in the notification of

water quality incidents. Between 1990 and 1995 the DWI analysed 317 incidents. Over

this period the number of incidents at service reservoirs decreased, but those arising in

the distribution system increased. In 1997, ninety-five incidents were notified—a slight

increase over previous years. However, this is thought to be due to increased diligence

in reporting as well as to difficulties in the distribution system. Of the ninety-five

incidents, fifty-two arose from the distribution system. Some were microbiological

failures, but thirty-one stemmed from bursts or as a result of operational activities

resulting in discoloured water in supply. Decisions on prosecution for alleged offences

under the Water Industry Act 1991 of supplying water unfit for human consumption

have been delegated to the DWI since 1996. In 1997 there were four successful, three

of Dwr Cymru, and one of Yorkshire Water, with fines totalling £37,500. A case against

South West Water was dismissed.

In 1997, nine incidents related to either an increase in the illness cryptosporidiosis

or the detection of cryptosporidium oocysts in water. Five were considered to be

associated with water supply. The most serious occurred in North London in February

1997, with 345 cases of the illness, showing a strong association with water from the

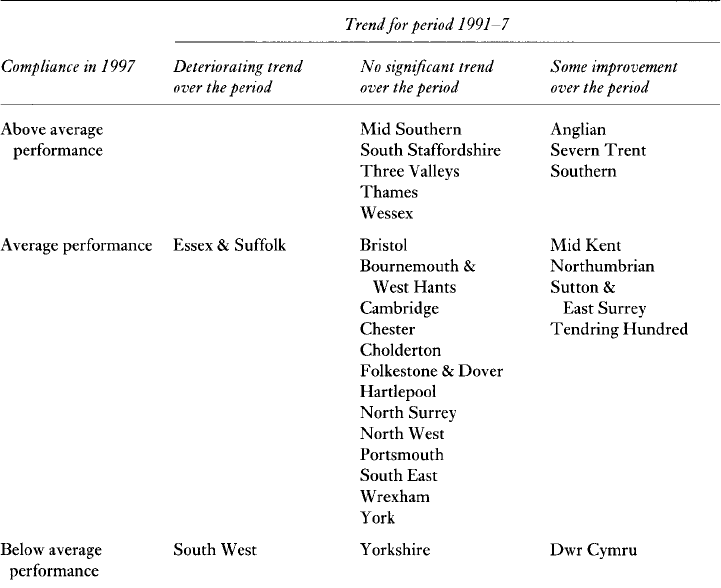

TABLE 2.3 Compliance for iron, 1991–7, for water companies in England and Wales

Source: Drinking Water Inspectorate, 1998, Chief Inspector’s Statement (on World Wide Web).

WATER RESOURCES

21

Clay Lane works of the Three Valleys Water Company. Continuous sampling for

cryptosporidium is now being proposed, and a treatment standard is likely to be

introduced in 1999.

Is there a geography of drinking water quality in England and Wales? This is difficult

to answer, as the Regulations embrace fifty-five different parameters. One approach is to

examine the percentage of total determinations which fail to reach the compliance standard.

No company has more than 1 per cent of determinations failing to comply, and only Sutton

and East Surrey and Cambridge Water Companies and North West Water have more than

half of 1 per cent non-compliance. At the other extreme, Chester, Cholderton, Folkestone

and Dover, and North Surrey Companies have less than a tenth of 1 per cent non-

compliance. However one incident may produce a number of different non-compliance

determinations, and as water quality is dependent upon a range of different characteristics

it is not felt meaningful to rely on such a simple single index. An alternative approach is

to recognise that consumers’ perceptions of quality depend very much on the aesthetic

factors and chemical qualities which determine the appearance of water, especially iron

content. Iron comes largely from rusty mains, but although it discolours water it is unlikely

to be harmful to health. Table 2.3 summarises 1997 compliance data for iron, in terms of

both average performance and trend over the period 1991–7, for all water companies for

which data are adequate. Thus Anglian, Severn Trent and Southern are achieving above

average performance, and are improving, whereas South West is below average, and

deteriorating. This relative company performance is a complex situation, but reflects both

the enforcement process and skill in operating the distribution systems, as well as many

other factors, including the historical development of the system, and difficulties

experienced during drier years. The standard for iron was met in 76.9 per cent of water

supply zones in 1997, and overall the trend is an improving one, as many companies have

major programmes to replace or reline corroded mains, which will take a further twelve

years to complete.

The impact of EC legislation

The Drinking Water Directive was adopted by the EC in 1980, and sets out standards of

water intended for human consumption. In 1995 the EC published proposals for a revised

Directive, and negotiations are proceeding. The Directive sets out standards for a range of

microbiological, physical and chemical properties to be met in drinking water. The

requirements were incorporated into UK legislation in 1989, and in some respects this

legislation is more stringent than the EC Directive. The financial impact on the UK water

industry and individual companies is immense. For example, it is estimated that East Scotland

Water requires £900 million in investment in the next few years in order to meet EC targets

on water quality. Between privatisation and March 1996 the companies invested £9 billion

on water services, including £3.4 billion specifically for improving drinking water standards.

Investment continues, with £4 billion planned for 1995 to 2005.

The Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive of 1991 passed into UK legislation in

1994. Its purpose is to protect the environment from the adverse effects of sewage

discharges, including an end to the dumping of sewage sludges at sea. Works must comply

with the requirements by various dates, between 1998 and 2005. There are currently about

6,500 sewage treatment works in England and Wales, and the estimated cost of work

VINCE GARDINER

22

necessary to comply with the Directive is £6 billion of capital investment, and £1 billion

per year in operating costs. The impact of this legislation could fall differentially on the

water companies, according to the amount of coastline and number of bathing beaches.

In effect, residents in popular holiday areas are having to pay through their higher water

charges to ensure that beaches remain clean for visitors. OFWAT have estimated that the

Environment Agency’s proposed wide-ranging environmental action plan could cost water

companies up to £11 billion and could add an extra £46 to the average household bill

between 2000 and 2005. For this reason, OFWAT have in 1998 proposed a ‘bucket and

spade’ tax on tourism to help pay this huge cost. The tax would be paid to local authorities

by local businesses that benefited from tourism, but would undoubtedly be passed on to

the holidaymaker, for example as higher prices for services and goods so diverse as hotel

rooms, fish and chips, donkey rides and flip-flops. Businesses reacted with alarm to this

proposal, which at the time of writing is out for consultation. This debate illustrates some

of the difficulties associated with multiple regulators of a privatised industry, whose

objectives may conflict with one another.

Financial aspects

One major source of complaint following privatisation was the size of water bills. It is,

however, important to note that average water bills are relatively stable or falling in real

terms, although sewerage bills have continued to rise for some customers to pay for

improved sewage treatment. The main factor which has forced water prices up has been a

huge programme of spending, which will amount to about £24 billion in the ten years

from 1994/5. At least half of this was to improve the quality of drinking water and sewage

treatment. Most of this expenditure is to meet legally enforceable UK and EC requirements

for better drinking water and a cleaner environment, as described above. Companies are

also meeting a substantial element of the costs from their own resources, from efficiency

savings, and from borrowing—in 1996/7 their spending exceeded income by over £700

million. The limits to prices companies are allowed to charge for water and services were

set initially in 1989 on privatisation, and are reviewed periodically by OFWAT. OFWAT

has been rigorous in restraining price increases wherever possible, consonant with allowing

companies to realise their planned investment programmes, and in the realisation that

companies have to make profits in order to attract investment to finance spending.

OFWAT’s report on the financial performance and capital investment of the water

companies in England and Wales shows that capital expenditure is now approximately

double the average level of that in the 1980s (inflation-adjusted), at over £3 billion per

year, so to that extent it can be argued that one of the primary aims of the whole privatisation

process has been achieved.

The public perception of water company performance has been heavily influenced by

the criticisms raised by both the media and politicians of the so-called ‘fat cat’ salaries and

bonuses received by the chairmen and other senior executives of the privatised companies,

despite a perceived lack of adequate performance. For example, in 1997 the chief executive

of Yorkshire Water received an extra £55,000 on top of his basic salary, which with benefits

brought his total remuneration to £298,000. This was set in the media against the background

of the company having failed to maintain supplies to customers in 1995, of it telling customers

that they faced being cut off if they had a bath, and that prices were being raised by 8.1 per

WATER RESOURCES

23

cent for unmetered and 6.1 per cent for metered supplies. Water companies counter that

their executives’ salaries are set as the market average for equivalent jobs in the sector.

OFWAT has no direct control over profits, share prices, dividends or chairmen’s salaries, all

of which have been bones of contention with the public. However, OFWAT and the

government have urged the utilities to adopt best practice in the supervision of board-room

pay by shareholders, and OFWAT are proposing to introduce objective comparative

information on company performance, so that performance-related pay policies can reflect

actual performance in the competitive market. The present government is also reported to

be looking into ways in which utility executive salaries are set, and how they could be linked

to standards of performance achieved by the companies.

It is important to note that the average cost of water in the UK is still low. For 1998/

9 the average water and sewerage bill works out at around 66p per day—a bath costs about

11p, a cycle of a washing machine the same, and watering the garden costs 75p. By contrast

heating the water for a bath or washing machine costs almost 20p, and a litre of bottled

water costs typically more than 50p. Average bills for water and sewerage range from

£,201 (Thames Water) to £354 (South West Water). For water, averages range from £158

(South East Water) to £73 (Portsmouth), and for sewerage from £102 (Thames) to £229

(South West Water). In the four years since OFWAT set price limits, average household

bills have increased by 4.5 per cent in real terms (17.8 per cent taking inflation into

account). In the same period, average household sewerage bills have increased by 10.5

per cent (24.6 per cent with inflation), this reflecting the greater investment necessary to

meet legal standards for treatment. For metered properties the average total bill is £223,

compared with £245 for unmeasured ones.

Traditionally, most water supplies to domestic properties in the UK have been

unmetered, and most charges for household water and sewerage services are still based

on the rateable value of the property (despite the fact that the domestic rating system ended

in 1990, with the consecutive advents of the Poll Tax, Community Charge and Council

Tax). However, in the last two decades metering has become more common, with 14 per

cent of households now having meters. Metering trials have been held, in which the majority

of customers found metering led to lower bills, although about one in five paid more than

previously. Metering has potentially an important role to play in conserving water

resources, and OFWAT believes that it is sensible to meter where it is cheap or economic

to do so—for example in new properties, for high non-essential users and where resources

are limited. However, consumer bodies have expressed concern that some 95 per cent of

domestic water consumption is essential, and therefore insensitive to changes in prices,

and heavy reliance on charges to encourage customers to reduce consumption by metering

is unlikely to be effective. OFWAT does not advocate either universal metering or a crash

programme of metering. Thirteen companies (out of twenty-eight) now offer free meters

and installation to every customer. There are some additional costs associated with

metering, and OFWAT has issued guidance as to how much of these it is reasonable to

pass on to customers. Initially the government planned to end rateable-value-based charging

by 2000, but this deadline has been extended.

Companies in the south and east of the country, whose water resources are most short,

are the most likely to adopt compulsory metering of existing properties; Anglia Water has

announced plans to meter 95 per cent of households by 2014–15. However, installing meters

in all homes would be uneconomic, and most companies are introducing meters selectively,

VINCE GARDINER

24

to large users (e.g. those using sprinklers and hosepipes, hotels and guest houses). Alternatives

to metering include a flat rate, or a banding system similar to that used for Council Tax,

based on the type of property.

Since 1945 water suppliers have had the legal power to disconnect customers’ water

supply (but not sewerage services) for non-payment of charges. This continued after

privatisation, and there was much public concern about the risk to public health caused

by disconnection, and unfair debt recovery procedures. OFWAT issued guidelines in

1992 to ensure companies acted consistently and fairly, and since then disconnection

figures have fallen consistently. For six years running disconnections from the water

supply for non-payment of bills have fallen. In 1998 1,907 household disconnections

were made (a 39 per cent reduction over the previous year); 1,774 non-household

disconnections were also made. Water companies have increasingly differentiated

between customers who are unable to pay, and those unwilling to pay—in 1991/2, 21,282

household disconnections were made. OFWAT believes that disconnection should be

used only as a last resort.

A major review of water-charging policy and tariffs was initiated by the issue of a

consultation paper in March 1998, and this is likely to result in more metering and more

sophisticated tariff structures than at present, with, for example, more cost-reflective tariffs

for large users, and seasonally variable tariffs.

Competition in the water industry

The Director-General of Water Services has duties to promote economy and efficiency, and

to help create effective competition. As the water industry is made up of local companies set

up in 1989 to provide water and sewerage services, as vertically integrated services with a

regional monopoly, normal market competition cannot exist. Opportunities for direct

competition are limited, as the cost of transportation of water across the clear geographical

boundaries of the companies is high. Any attempt to duplicate the distribution system would

lead to prohibitive increases in costs, and there is no independent production of water possible.

However comparative competition can help to achieve results similar to those achieved in a

competitive market. OFWAT does this by comparing the performance of individual

companies and then setting price limits that give the companies incentive to increase their

efficiency. Comparisons between companies can also lead to the adoption of best practice

so that all customers can benefit. The consultation paper issued in March 1998 is also

addressing issues related to competition, in increasing consumer choice and developing more

cost-reflective tariffs.

In addition, a direct mechanism for at least limited direct competition and

choice has been developed, as the so-called ‘inset-appointments’. These can be

granted to a company to provide water and/or sewerage services either on a greenfield

site without water supply, within the existing appointee’s area, or to a site supplied

with 250 megalitres or more of water per year. An inset appointment can be granted

to an existing company, or a new entrant to the industry; a large customer can

effectively become its own supplier by setting up an affiliated company to be the

appointee. Water for an inset appointee can come from a new source, but in practice

is more likely to come from a connection to the existing appointee. There is some

limited evidence that the procedure, or the threat of it, is beginning to be effective

WATER RESOURCES

25

in driving down prices to large users. In the charging year 1998/9 some twenty-two

(of twenty-eight) companies will have large user tariffs and three (of ten) will have

large user sewerage tariffs, resulting in a reduction of 15–30 per cent in prices. The

first two successful inset appointments were granted in 1997, to a large chicken

processing firm and to a Royal Air Force station, both in Anglian Water’s area. A

third application, which will involve a new entrant to the industry, Albion Water

Ltd, has been approved, to supply a paper manufacturer in the Dwr Cymru area.

Other changes to legislation are currently under discussion in order to facilitate

competition, including changes to abstraction licensing.

Leakage and efficiency

Considerable media and public concern has been expressed about leakage. Alarmingly,

almost a quarter of the water which is expensively abstracted from sources or stored

in reservoirs, and then treated to potable quality by the water companies, never reaches

the consumers as it is lost from leaking mains en route. Losses for individual companies

vary from 15 per cent to 38 per cent. In 1995/6, almost 5,000 ml/d were lost. OFWAT

has monitored this closely, and asked the industry to set its own targets for leakage

reduction. In the first year the water industry in England and Wales achieved a 9.5 per

cent reduction, and from 1996/7 to 1997/8 it managed to reduce leakage overall by

more than 12 per cent, with South West Water, Folkestone and Dover and Hartlepool

companies reporting reductions of more than 20 per cent. Savings of over 1,000 ml/

d have been made nationally in the last two years. However, three companies (Anglian,

Portsmouth and Mid Kent) failed to meet their self-set leakage targets for 1997/8, and

the mild winter probably helped many others, who only barely met their targets.

Thames Water remains a particular concern, with leakage considerably above the

industry average. Henceforth, more stringent OFWAT-set targets will be used to judge

company performance in reducing leakage, and it is expected that the biggest fall in

leakage will come in 1998/9.

Leakage is only one aspect of efficient use of water. At a Water Summit held in May

1997 companies were asked to review their water efficiency plans in line with the

government’s ten-point plan. Since 1996 companies have had a duty to promote the efficient

use of water, although co-ordinated strategies have been slow to emerge in some cases.

However, particular initiatives introduced by many include providing a freephone leakline

number, free supply pipe repairs, free water audits, and a free cistern device (e.g. Thames’

‘hippo’) to reduce toilet flushing volumes (of which 4 million have been distributed).

Companies now have to monitor and report to OFWAT on their progress against strategies

to promote efficient water use.

There are sufficient sewers in England and Wales to go more than seven times around

the world. Over 1,400 kilometres have been renewed since privatisation, and, despite some

media campaigns, there is no evidence nationally of long-term deterioration in serviceability

of sewer networks. Sewers can last a very long time. Indeed, the performance of the system

is improving—since 1992/3 the number of properties flooded by sewers has fallen from

10,858 to 4,627, and there is no evidence of an increase in the number of sewer collapses

over the last fifteen years. The companies spend about £80 million each year on maintenance,

and about £150 million on renewals.