Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

RON JOHNSTON

6

and more people (though not only the excluded) are seeking relief through addictive drugs

(another source of economic enterprise—albeit illegal, except in the cases of nicotine and

alcohol). Poverty, unemployment, addiction and crime interact and generate spirals of decay.

They cause stresses within households and initiate the break-up of many partnerships and

families. Sheffield illustrates this for us through the film The Full Monty, whose underlying

theme is not just of men made unemployed by the collapse of the steel industry but also of

men without prospects, even hope; their roles in life are increasingly taken over by women

who succeed in the new service economy and who make men feel not only redundant but

also obsolescent. In some places, it is not just individual households that have fractured

under such strains (with consequent implications for housing and child-rearing) but entire

communities. The pit villages of South Yorkshire illustrate this, and another film —Brassed

Off—delivers the message superbly. The miners’ strike empowered women there for the

first time, both economically and politically, and when the strike was over many were

unwilling to return to their former domestic roles as expected by the men.

Social and cultural changes have been manifold within the culture of contentment in

the more affluent sectors of the economy too. Changing attitudes to childbearing and child-

rearing accompanied the increased participation of women in the labour force throughout

their lives, with a consequent expansion in the number of dual-career families dependent on

a range of formal and informal ways of providing childcare. Many of those families, especially

in the professions, involve one or both of the partners in long-distance commuting: substantial

numbers operate two homes during the working week. Commuting patterns are increasingly

complex and cross-cutting: many depend on private transport and contribute to the build-up

of traffic and its associated problems in rush-hours which begin on Sunday evenings and

end on Saturday mornings.

Social, cultural and economic changes are intertwined and inscribed in the country’s

landscapes. They interact with the political processes, and these too have been very

substantially modified in recent years. The post-war settlement which lasted from 1945

until the late 1970s was based on the goals of full employment and the reduction of

inequalities, enshrined in the five pillars of the welfare state—combating want, disease,

ignorance, squalor and idleness. This came under increasing attack from economists and

right-wing politicians as both unsustainable and a major constraint on the individual and

corporate enterprise necessary for successful economic restructuring in a globalising world:

the corporate-welfare state’s high and spiralling costs meant that taxation rates were too

high to encourage risk-taking while the necessary government borrowing both led to high

interest rates (another brake on investment and enterprise) and stimulated inflation. By the

mid-1990s, the case for reforming the welfare state was accepted by all political parties.

The critique of the welfare state was part of a broader attack on the state’s role in

contemporary society, accompanied by a rhetoric that it encouraged dependency and

discouraged self-help. The state was implicated in too many aspects of people’s lives, it

was argued, and its role should be reduced: people should take more control of their

present and future, and more of their necessities should be provided through much more

efficient and effective market mechanisms. At the same time, those services which remained

with the state—such as health-care and education—should be subject to the rigours of the

marketplace: many others, such as the public utilities, should be returned to that

marketplace, with the state, if necessary, acting only as a regulator to safeguard society’s

interests.

INTRODUCTION

7

Much of this rhetoric was implemented during the 1980s and 1990s, creating a new

political map of the United Kingdom. One of the main mechanisms chosen was to place a

wide range of public services—such as health-care trusts and many educational institutions

—under the management of non-elected boards of directors and governors which were

accountable to central government for their expenditure and the achievement of specified

targets, but not subject to direct democratic control. These quangos, as they became known,

were dominated by political appointees who accepted the pervasive rhetoric. Complementing

this trend was a decline in the role of the democratic state: central government oversight of

the detailed implementation of policies was reduced while local government powers were

eroded and in some cases eliminated.

Once again, Sheffield Attercliffe illustrates what has happened. Economic and social

regeneration was vested not in the democratically elected and accountable Sheffield City

Council (South Yorkshire County Council having already been eliminated as redundant in

1987) but in a quango—the Lower Don Development Corporation, whose membership was

dominated by government appointees (most of them businessmen) and who were responsible

for developing public-private partnerships to redevelop the valley. The City Council’s

responsibilities for land-use planning were substantially reduced and control of what went

on in a substantial component of their city was largely taken away from Sheffield residents.

At the same time, local government powers in other areas were reduced —they were required

to sell their council housing to sitting tenants at cut-price rates, for example, and prevented

from using the receipts to build more homes. Eventually, even those local councils dominated

by large left-wing Labour majorities were forced to accept the new ideology and

methodologies—radical Sheffield, in Patrick Seyd’s telling phrase, shifted its emphasis from

socialism to entrepreneurialism, replacing its role as a focus for anti-Thatcherism opposition

by joining the competition for inward investment in an ‘enterprise-favourable environment’,

while some of its leaders abandoned their socialist credentials and became avid supporters

of New Labour.

Local government was restructured too, by legislative fiat in Scotland, Wales and

Northern Ireland, and by a complex system of pseudo-consultation in England that largely

failed, producing a complicated system of authorities. The goal was to make local government

more efficient and effective, reaping the economies of scale and scope—though the scope

could be that of the purchaser of services from outside contractors rather than the traditional

role of provider.

Government became both more centralised and less open to democratic accountability:

even the functions remaining with the local state apparatus were under strict central control,

notably (but not only) on the amount raised through local taxation. There was a growing

democratic deficit. Much of this occurred when the country was very divided politically:

the northern areas which suffered most were predominantly represented at Westminster and

governed locally by the Labour Party, which was in opposition nationally from 1979 until

1997, whereas almost all of the booming southern regions’ MPs were Conservatives, as

were a majority of councillors in most of their local governments until the Tory fall from

grace after 1992. The national political map changed in 1997, not because the northern

regions were becoming much more prosperous again relative to their southern counterparts

but because the electorate in the latter were increasingly disillusioned with the government,

with its divisions (especially over the major issue of British participation in the European

Union), sleaze, lack of leadership, and failed macro-economic policies (as exemplified by

8

Black Wednesday in September 1992 when sterling was forced out of the Exchange Rate

Mechanism, the precursor of European Monetary Union). New Labour replaced it with a

government having the largest House of Commons majority for sixty years: it won middle-

class support and seats in the south, not because it offered an alternative macro-economic

policy—indeed, it pledged that it would continue many of its opponents’ policies—but

because it looked better able to continue providing much of what had been delivered by the

Conservatives in the 1980s.

The democratic deficit has stimulated calls for constitutional reform, though much

of this has been elite-driven rather than populist. The main exception has been in Scotland,

where pressure for a devolved Parliament with tax-raising powers was substantially

confirmed in a 1997 referendum and the first elections were held in 1999. The Welsh also

voted in 1997 (by a slim majority) for a weaker form of devolution—a Welsh Assembly,

also elected in 1999; following the 1998 ‘Good Friday Agreement’ a devolved Assembly

was rapidly created in Northern Ireland, as part of a programme to end thirty years of

bloody inter-community strife there, with its first elections only three months later; and

Londoners voted in May 1998 for their own reconstituted metropolitan government led

by a separately elected ‘strong mayor’. There is considerable pressure for devolution to

some English regions—notably the North East and the South West—too. The political

map is being redrawn yet again, with potential implications for economic and social

directions.

All of this change is taking place on a landscape which is a palimpsest of many

thousands of years of human occupance, and which itself presents major constraints and

opportunities. It is experiencing growing demands to provide the fundamentals needed for

affluent living, not only agricultural products but also the raw materials for construction

projects; it is under pressure to contain those lifestyles, not least the further 4 million homes

which the government estimates are required over the next two decades; it is required to

absorb an increasing volume of waste materials; and it is affected by various global

environmental changes. Conservation and preservation of physical landscapes and the human

imprint upon them is in increasing conflict with those demands, and makes sustainable

living for future generations increasingly difficult to ensure.

All of the change described here has taken place in the last twenty years: it

represents another epoch in the remaking of the UK landscape. Each edition of this

book has appeared at what seemed to be a critical moment in that continual process: in

1983, at the end of a long period of reconstruction after the major slump of the early

1930s, punctuated by a world war; in 1991, after a decade of change as the welfare state

came under fire and the assumed superiority of the market was being put to the test; and

now in 1999 in the early stages of a new approach to that experiment. The basic themes

identified here are developed in the various chapters that follow; who can guess how

Robert Waller will represent their playing out in Sheffield Attercliffe before the general

election of 2007?

9

Chapter 2

Water resources

Vince Gardiner

In concluding the chapter on water resources in the previous edition of this book, Park said:

‘The water industry in the United Kingdom during the 1990s will look and act very differently

from how it did in the 1980s’ (Park 1991:169). This has undoubtedly proved to be the case,

with the privatisation of the water industry, legislation concerning water quality, and changes

in patterns of both demand and supply all interacting to ensure rising public awareness of,

interest in and controversy about water resource issues. In this Chapter the basic geography

of use and supply of water is outlined, and then developments and events during the 1990s

are discussed. The major theme of this discussion is the changing structure of the water

industry, especially in England and Wales.

The basic geography of water use and supply in the

United Kingdom

Although it is not always possible to differentiate clearly between supply of and demand for

water (see Park’s discussion, 1991), it is possible to think in at least conceptual terms of the

ways in which water is used, and the sources of supply of that water. In the United Kingdom

water is used for a great variety of purposes, which may be broadly categorised as domestic,

industrial and agricultural. Total use is discussed first, before individual uses are examined.

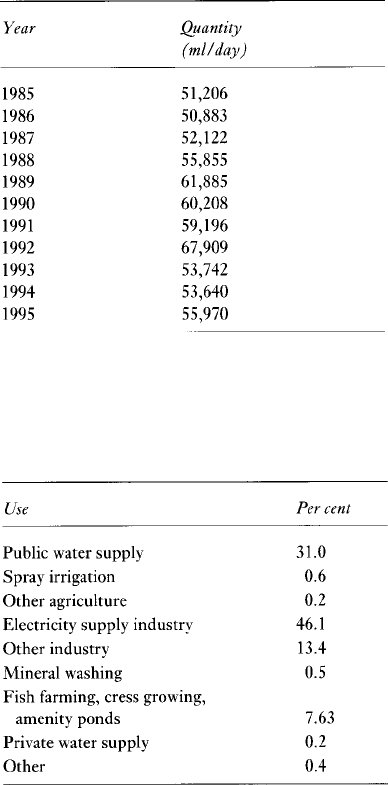

Total abstraction of water from all sources in England and Wales is shown in Table 2.1.

Although there is significant year-to-year variation, there is little evidence of a systematic trend

of increasing abstraction. In 1995, the total abstraction in England and Wales was divided as in

Table 2.2. About a third was used for public water supply, by the water companies; this includes

both water used in homes and water supplied to a wide variety of commercial, business and public

buildings. Figures for water put into public supply over the last twenty years show a 15 per cent

increase from 1974/5 to 1994/5, but only a 3 per cent increase within the last decade. Although

OFWAT (see p. 16) suggested in 1994 that the demand for public water supply was virtually

VINCE GARDINER

10

static, and would remain so until 2014– 15,

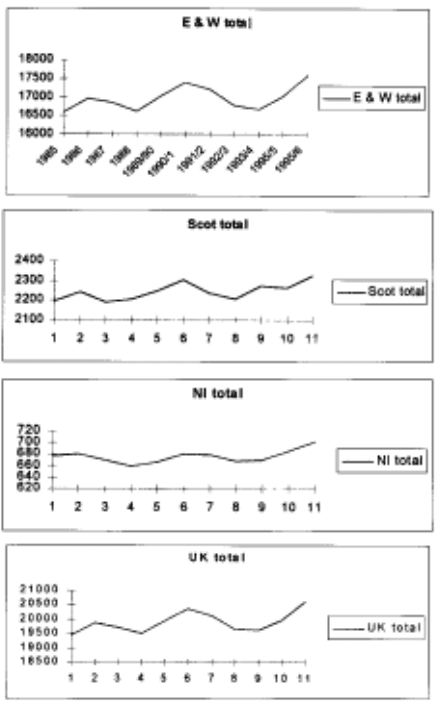

here is some suggestion (Figure 2.1) that

periodic and almost cyclic fluctuations in

demand are superimposed on a generally

rising trend. Troughs in total demand

occurred in 1988 and the early 1990s, but

overall demand continues to rise slowly,

for both the UK as a whole and its

constituent countries. A more detailed

analysis of the uses of water put into public

water supply in particular regions is shown

in Figure 2.2 for the end of the period

considered above.

Although the demand for water

supply fell until 1993, there has since been

an upturn in demand for both metered and

unmetered supplies. The growth in

demand for metered supplies varies from

company to company, being least in the

areas served by the South West and

Yorkshire companies, where rates are high

and there have been strong public

campaigns against charges. For

unmetered supplies again variation exists,

with North West, Southern, South West

and Yorkshire not indicating consistent

growth, unlike in the other areas.

Domestic use accounts for about

40 per cent of all water abstracted for

the public supply, and is affected by

increasing affluence and higher

standards of living. The average

household uses about 380 litres per day,

or about 160 litres for every person, one-

third of which is used for each of toilet

flushing and miscellaneous uses. Only

around 5 litres per day is used for

drinking and cooking. The main

increases in household water use are for

personal hygiene and for watering of

gardens, both of which are most significant in summer, when supplies are under most stress.

The accuracy of forecasts of future demand will remain heavily dependent on predictions

of economic, lifestyle and cultural changes within the communities of consumers, and are

likely to be further influenced by climatic change.

About half of the water abstracted in 1995 in England and Wales went to the electricity supply

industry, mainly for hydropower. Other industry accounted for about an eighth of the total. Only a

TABLE 2.1 Estimated actual abstractions from all

surface and groundwater sources in England and

Wales, 1985–95 (for limitations of these data, see

source)

Source: Abstracted from data in the Department of

the Environment, Transport and the Regions

(DETR) World Wide Web pages.

TABLE 2.2 Total abstraction of water in England

and Wales, 1995

Source: Abstracted from data in the DETR World

Wide Web pages.

WATER RESOURCES

11

very small proportion was used for

irrigation in agriculture (less than 1

per cent), although there is an

underlying trend for this to increase.

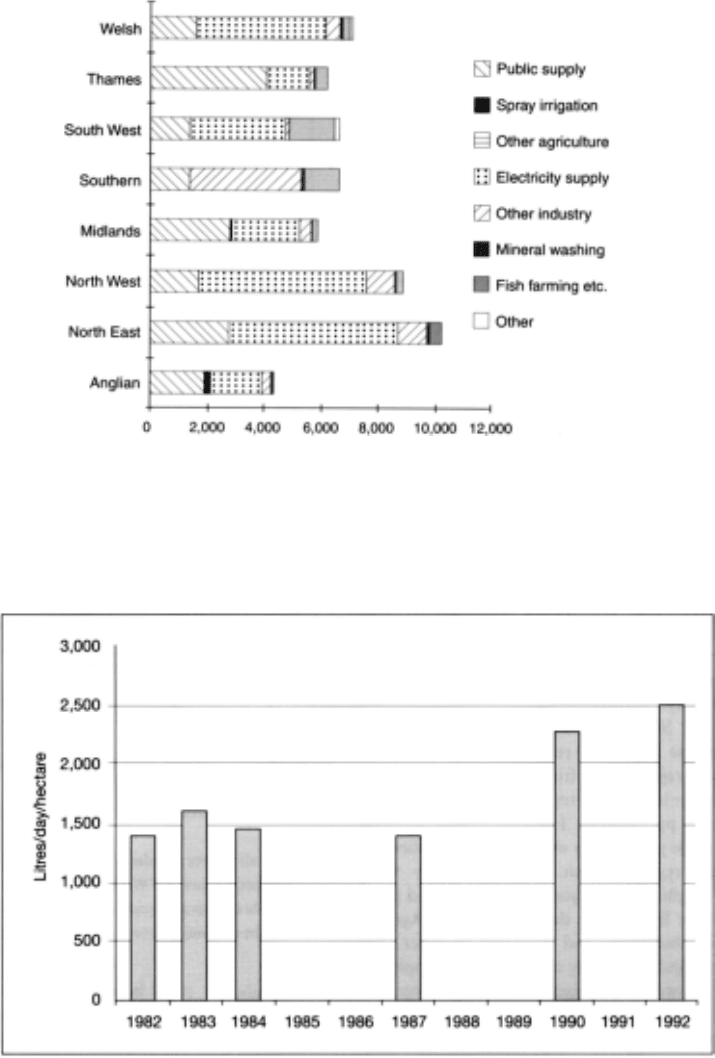

Although spray irrigation forms

only a very small proportion of the

total demand for water, it can be very

significant because the water is

immediately lost as a resource, and

it occurs in a concentrated period of

the year, usually in the driest areas,

and in driest years (Figure 2.3). Over

the last forty years changes in

agricultural practices have moved

the emphasis in irrigation away from

increasing yields and towards

securing better quality and a more

reliable supply. Irrigation rates have

doubled from approximately 1,300

litres per day per hectare in 1982 to

2,500 litres per day per hectare in

1992, although these rates depend

greatly on weather conditions.

Potatoes account for most of the

water used (59 per cent in 1992),

closely followed by other vegetables

(see also Chapters 5 and 19).

There has been a general

reduction in the amount of water

abstracted for industry and

general agricultural purposes

over the last decade, attributed

partly to increased efficiency in

use, and partly to the shift in the

national economy away from

manufacturing and towards

service industries using less water

(see Chapter 7). This decline has

however been accompanied by a

general increase in the demand

for water for irrigation, fish farming and associated uses, and hydropower.

Since 1989, the vast majority of people in the UK have received their water and

sewerage services from companies appointed under licence and regulated by official bodies

(see pp. 16–17). However, such services can be provided by others. These supplies are not

regulated, but need to comply with recognised water quality standards, and need to be licensed

by the Environment Agency for abstraction and discharge of water. An unregulated supply

FIGURE 2.1 Trends in public water supply in the United

Kingdom, 1985–96

Source: From figures in the DETR World Wide Web

pages.

Note: For all figures and data in this chapter derived

from Environment Agency, OFWAT and DETR data,

there are considerable caveats and qualifications to be

attached to the data, and the original source should be

consulted.

VINCE GARDINER

12

FIGURE 2.2 Variations in use of water abstracted from surface and groundwater

for Environment Agency Regions, 1995

Source: From figures in the DETR World Wide Web pages.

FIGURE 2.3 Irrigation water used per hectare of irrigated land, England and Wales (litres per day)

Source: Derived from figure in the DETR World Wide Web pages.

WATER RESOURCES

13

could be a well supplying the owner’s premises and perhaps several neighbouring sites, or

could be a larger supply serving a village through a pipe network. There are around 50,000

self-contained water supplies in England and Wales which supply more than one property,

and many industrial customers have their own sewage treatment works; 4 per cent of domestic

properties in England and Wales are not connected to main sewers, having either individual

septic tanks and cesspools, or private treatment works.

Sources of water

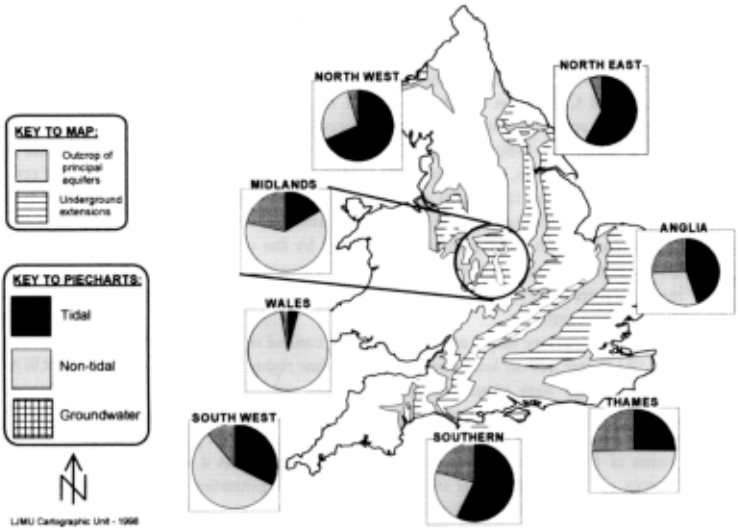

Water for water supply in the United Kingdom originates from both surface water, as rivers

and lakes, and from groundwater. Although most parts of the country draw water from both

sources, the balance between the two varies markedly, depending on both the availability of

adequate surface water supplies and the suitability of the underlying rocks to provide

groundwater (Figure 2.4). In general, the wetter north and west parts of the UK, which tend to

be underlain by rocks which are poor aquifers, rely predominantly on surface water, whereas

the drier south and east, which also have more aquifers, are more reliant on groundwater.

Substantial amounts of water are also drawn from estuaries for industrial purposes,

especially for cooling in electricity generation. It should be noted that many industrial uses of

water, for example for hydroelectric power and for cooling, and fish farming, do not ultimately

consume water resources, as the water is shortly returned to surface water within the hydrological

FIGURE 2.4 Estimated abstractions from various sources of water, 1995

Source: From data in the DETR World Wide Web pages.

VINCE GARDINER

14

cycle, albeit in some cases as of degraded quality. In contrast, some uses, such as spray irrigation

and abstractions for evaporative cooling, do represent a loss to the water resource.

The framework of public water supply

The present legislative, administrative and organisational framework for water resource

management in the UK differs considerably from that which existed when the previous

editions of this book were published. The public supply of water in the United Kingdom

was first carried out by a multitude of private water companies and local authorities, with

over 3,000 such bodies before the First World War. The 1945 Water Act encouraged

amalgamations, and by 1963 the numbers had reduced to 100 water boards, fifty local

authorities and twenty-nine privately owned statutory water companies—some of which had

been operating since the seventeenth century. However, the need was recognised for larger

units which could provide the integrated management of water resources within major river

basins, and ten Regional Water Authorities (RWAs) were set up by the 1974 Water Act, as

public undertakings. The twenty-nine statutory water companies then in existence acted as

their agents for water supply, with the water supply and disposal functions of numerous

local authorities being combined together into a river basin framework under the water

authorities. The ten multipurpose water authorities, based on major river basins, had a wide

range of responsibilities connected with the water cycle, including conservation, pollution,

drainage, fisheries, water supply and sewerage. The majority of their members were from

local authorities, and they calculated customers’ bills on the basis of rateable values.

In the second half of the 1970s, however, there was insufficient maintenance of and

capital investment in the water distribution system, whilst the RWAs were accused of

individually building substantial empires, including capital investment in large supply

schemes such as the Carsington (Derbyshire) and Kielder (Northumberland) reservoir

schemes, which were arguably neither efficient nor necessary within the national context.

During the 1980s, the RWAs increasingly became subject to government targets and

financial controls, similar to those of the nationalised industries. At a time of economic recession

they were faced with a need for increased expenditure and investment in capital projects to

meet increased water quality and environmental standards, mainly resulting from EC legislation.

Their budgets were squeezed by the conflicting pressures of the need for investment and limits

on public funding and borrowing. Prices inevitably rose, and there was increasing pressure to

find alternative sources of finance for the required environmental and quality improvements.

A preliminary move away from public control occurred in 1983, when as a result of

the 1983 Water Act the local authorities lost some rights of representation on the RWAs, and

their meetings were closed to the press and public, although Consumer Consultative

Committees were set up as some degree of compensation. A discussion paper on privatisation

of the industry was published in 1986, which advocated privatisation of the RWAs as a means

of freeing them from government control, and as a means of ensuring access to sources of

funds for capital investments. Many organisations and individuals expressed concern about

privatising the regulatory aspects of the water authorities, seeing possible conflicts in a role

combining responsibility for water quality with that for sewage disposal. Despite concerted

campaigns, especially from environmentalists and those opposed to the privatisation of the

regulatory role of the RWAs, the 1989 Water Act allowed the RWAs to be sold off as part of

the Conservative government’s programme of privatisation. Independent regulatory bodies

WATER RESOURCES

15

were set up: the National Rivers Authority to deal with water quality in natural water bodies;

the Director-General of Water Services (OFWAT) to regulate prices in the industry; and the

Drinking Water Inspectorate, to deal with drinking water quality. The then twenty-nine private

companies were brought under the same regulatory controls

While privatisation was being discussed, the implications of EC legislation on water

quality standards became more apparent. In recognition of this, the government wrote off

£5 billion of the industry’s debts before privatisation, and endowed them with a further £1.6

billion cash injection (the so-called ‘green dowry’). Shares in the ten water companies which

replaced the RWAs were offered for sale in November 1989, and the offer was oversubscribed.

Most of the private water-only companies in existence before 1989 have since re-registered

under the Companies Act 1985, so that their earlier restrictions on borrowing and paying of

dividend no longer apply. Since 1989, twelve of these companies which were in common

ownership have been brought together under five single licences.

Under the present system the privatised water companies, comprising the ten large

water service (water supply and sewerage) companies, resulting from the sale of the former

RWAs, and the much smaller water supply companies which had never been absorbed into

the RWAs, have a statutory duty to maintain supplies. Under the 1989 Act regulatory roles

were given to three new agencies, the National Rivers Authority, OFWAT and the DWI (see

pp. 16–17). A regulator was felt necessary, as water formed a natural monopoly. Regulation

relies on comparative competition and on competition for capital in the financial markets.

OFWAT has allowed prices charged for water to be increased above the rate of inflation, but

only in order to allow for investments necessary in order to meet raised standards, although

there are those who believe that this is a failure of the regulatory system. It has been argued

that the mergers which have taken place have reduced the scope for comparative competition.

Since privatisation, the industry has been affected by further legislation, which has

consolidated existing legislation, and strengthened the powers of regulators. In addition, in

1994, the government relinquished its special (‘Golden Share’) holdings in the water and

sewerage companies, which has exposed them to the potential of merger and take-over as

for any other quoted company. However the Monopolies and Mergers Commission has to

be consulted if any proposal would result in a new water enterprise with gross assets exceeding

£30 million, and there is also European legislation governing certain large mergers.

Notwithstanding this, since 1989 several of the water-only companies have been taken over

by major shareholders, and their number has been reduced by amalgamations, to eighteen

at the time of writing. Mergers have occurred between various utility companies of different

kinds (e.g. North West Water and NORWEB, the electricity company, 1995); between water-

only and water and sewerage utilities (e.g. Northumbrian Water and North East Water in

1995); and between water-only companies (e.g. East Surrey Water and Sutton Water in 1995).

Some water and sewerage companies are now part of multi-utility groups (for example North

West Water, Dwr Cymru and Southern Water Services are all joined to a regulated electricity

business), and these multi-utility groups are increasingly moving into other competitive utility

businesses such as telecommunications and gas. A number of the smaller water-only

companies have also entered into the competitive gas business. Each company is required

to operate at arm’s length from its associates, and without cross-subsidy, and further

investigations are continuing into trading relationships and the transparency of financial

performance. Some of these groupings have an international dimension, for example as in

the linking of Southern Water and Scottish Power, and the merger of Northumbrian Water