FTA (изд-во). Flexography: Principles And Practices. Vol.1-6

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

times. Negatives are not used during back

exposure. The exact back-exposure times

are determined using a back-exposure step-

test procedure.

Main Exposure

The plate material is turned over and the

coversheet is removed. Clean negatives are

placed emulsion down on the material and

the vacuum sheet is smoothed over the

material. In systems equipped with dual light

sources, the plate material does not need to

be turned and this step is combined with the

back-exposure step. The UV lights are then

turned on for a specified amount of time.

When the plate material is exposed through

the negative with UV light, the areas corre-

sponding to clear areas on the photographic

negative are hardened. The areas, corre-

sponding to the black areas in the negative

remain unexposed (uncured).

Face-test Exposures

Face-test exposures should be conducted

to determine the exposures necessary to

reproduce the copy detail. Image-stepped

test negatives containing a variety of copy

detail and tonal values are available from

various suppliers. Once the desired back

exposure is established, these images are

face exposed for various periods to establish

the times necessary for plate production.

Plate Processing

After exposure, the plate is ready to be

processed in the washout unit. This unit

removes uncured photopolymer material,

leaving the cured image in relief. A process-

ing solution together with a brushing action

removes the uncured material, which then

dissolves in the solution. Washout condi-

tions may vary considerably from one manu-

facturer’s system to another. Most plate

material suppliers also supply an alternative,

more environmentally friendly, line of sol-

vents than those marketed in the past. Plate-

processing units come in both rotary and in-

line versions. Some important considera-

tions in processing are brush pressure and

replenishment of solvent chemistry.

Typically, short washout time can cause

shallow relief, tacky and uneven background

(floor), and surface scum (dried polymer on

image surface). Long washout time can

cause damaged or missing characters,

excessive swelling and uneven plates.

Consult the appropriate polymer processing

manuals for the best processing times.

Preliminary Inspection

After a brief time in the dryer, the plates

should be inspected and wiped to remove the

thin film of residue that may remain on the

print surface of the plate. Failure to remove

this film will result in the appearance of

“orange peel” or dry-down spots, which may

appear principally on solid areas and around

reverses. The plate should also be checked

for correct processing and floor formation. A

poorly processed plate may be reclaimed by

reprocessing at the correct settings.

Plate Drying

When solid-sheet plates are removed from

the washout unit, they are soft, swollen and

tacky. Processing solvent is absorbed into

the plate during washout, causing the plate

to swell. As a result, straight lines become

wavy and type is distorted. Oven drying will

evaporate this absorbed solvent. The plate’s

swelling will reduce, making the images

sharp and clean. A fully dried plate will

return to the original gauge of the material.

Time and temperature must be controlled

for proper plate drying. Plates not dried suf-

ficiently may be swollen and uneven in

gauge. If the drying temperature exceeds

140° F (60° C), the polyester backing may

shrink and cause the plate’s dimension to

change. Process-color plates generally take

longer to dry than line plates. Follow the

plate material and equipment supplier’s rec-

PLATES 35

36 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

ommendations for setting dryer tempera-

tures and times.

Plates will still be tacky when removed

from the dryer, and care must be taken not

to touch the surface of the plates because

fingerprints will be left on the finished plate.

After drying is complete, the plate back

should be wiped with clean solvent and a

lint-free wipe to remove any polymer residue

prior to light finishing.

Light Finishing and Post-exposure

Light finishing and post-exposure are per-

formed image-side-up in the unit. Light fin-

ishing eliminates surface tackiness of the

dried sheet photopolymer plate. This

process uses shortwave (germicidal) UV-C

light to finish the plates before post-expo-

sure. Light finishing times will vary with

plate type. Prolonged exposure in the light-

finishing unit can cause premature cracking

of the print surface during subsequent print-

ing and storage.

After the plates are light-finished, they

must be post-exposed using UV-A light to

complete the polymerization process, ensur-

ing the whole plate is fully cured and has the

optimum physical properties for printing.

Light finishing and post-exposure may be

run simultaneously on the appropriate

equipment. Table 7 summarizes conditions

in order to maintain plate quality.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Problems in plate performance can usually

be traced to changes in platemaking condi-

tions or press techniques. Appendix Ccovers

some common photopolymer plate problems

and offers suggested remedies. Note that a

problem may be caused by a combination of

factors (for example a “wavy line” can be

caused by a combination of inadequate expo-

sure time and long washout time).

Table 7

TRIMMING PLATES:

■ Use a sharp blade, to avoid creating nicks or

fuzzy edges

■ Make cuts from the backing sheet (preferred)

INSPECT PLATES FOR:

■ Thickness and levelness

■ Relief

■ Surface finish, free from blemishes and pits

■ Reverse-image depth

■ Register line rip marks

■ Hardness (durometer)

PROPER PLATE HANDLING AND STORAGE:

■ Avoid 180° bends

■ Use a soft-bristled brush for cleaning

■ Avoid kinking the backing sheet

■ Use proper washup solvents

■ Clean plates before storage

■ Store plates in cool, dry and dark areas

MAINTAINING PLATE QUALITY

Checklist

P

lates, particularly the laser-

engraved variety, have been

directly imaged for a number of

years. Direct-imaging technolo-

gy is now being applied to sheet

photopolymers, as well as rub-

ber, but in the case of sheet photopolymers,

conventional processing is still required

after the direct-imaging setup.

LASER-ENGRAVED PLATES

Laser-engraved rubber plates are pro-

duced by engraving the rubber compound

with a high energy laser unit similar to that

used when producing ceramic anilox rolls.

The high energy laser ablates the unwanted

rubber in the relief area of the plate, leaving

the raised image. Laser-engraved rubber

plates combine the excellent printing char-

acteristics of rubber and direct imaging from

computer-generated artwork, thereby elimi-

nating the need for negative films. Most

images for laser-engraved plates are pro-

duced from computer-generated artwork.

The engraving process is, however, time

consuming, especially with thicker plates

like those used for direct corrugated print-

ing. Laser technology is continually improv-

ing, increasing both the image fidelity and

production speeds.

Rubber used for the printing plate is sup-

plied either as prevulcanized sheets of spe-

cific thickness for the range of plate gauges

used in flexography and letterpress, or raw

gum compounds for design-roll applications.

The prevulcanized sheet material may be

imaged on a flatbed machine or on a rotary

drum laser-imaging machine. Both types of

machines are directly linked to a raster

image processor (RIP) which drives the

laser. Figure

2!

shows the dot structure of

the finished plate.

LASER ABLATION OF LIQUID

PHOTOPOLYMERS

Laser ablation works very well with liquid

photopolymers. The photopolymer is cast on

a standard exposure unit and a large, solid

plate is made. This plate is produced in the

normal fashion, and then imaged using a

laser unit similar to laser engraving a rubber

plate. Ablation time is typically shorter than

ablation of rubber. Dual-durometer capped

plates have shown excellent imaging and

printing results when laser ablated. Table 8

summarizes the advantages and disadvan-

tages of laser ablation.

DESIGN ROLLS

Many designs for floor coverings, wallpa-

PLATES 37

Direct-Imaged Plates

2!

This laser-engraved

image profile reveals

dot structure of the

finished rubber plate.

2!

38 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

pers and flexible packaging have continuous

patterns or solid-color backgrounds whose

appearance is improved by eliminating

seams. For good decorative printing, the

absence of “plate breaks” is virtually manda-

tory. Seamless pattern printing is the most

obvious feature and is the main reason for

using laser-engraved design-roll cylinders

(Figure

2@

). Table 9 summarizes the condi-

tions to consider for design roll use.

In flexible packaging and some other flex-

ographic applications, it is not unusual for

the printer to use a laser-engraved design

roll, together with one or more conventional

plate-mounted rolls, when printing a multi-

color design. Laser-engraved design rolls are

often used for multicolor images being

mated to cutting dies or patterned emboss-

ing rolls, requiring a degree of registration

accuracy difficult to achieve with conven-

tional plate-mounting techniques.

Various rubber compounds, polyurethane

materials or photopolymers may be applied

to the surface of a standard press cylinder

and cured in place to form a continuous

sleeve of flexible plate material. The print

surface of the design roll is preground,

before laser-engraving, producing a high

level of concentricity. This concentricity,

together with a sharp, clean laser-engraved

relief, give design rolls a very long press life

– several times that of most individually

mounted printing plates.

PREPARING THE ROLL

Laser-engraved design rolls can be created

on practically any print-cylinder base – inte-

gral-shaft cylinders, de-mountable metal

cylinders or rigid metal sleeves – on which

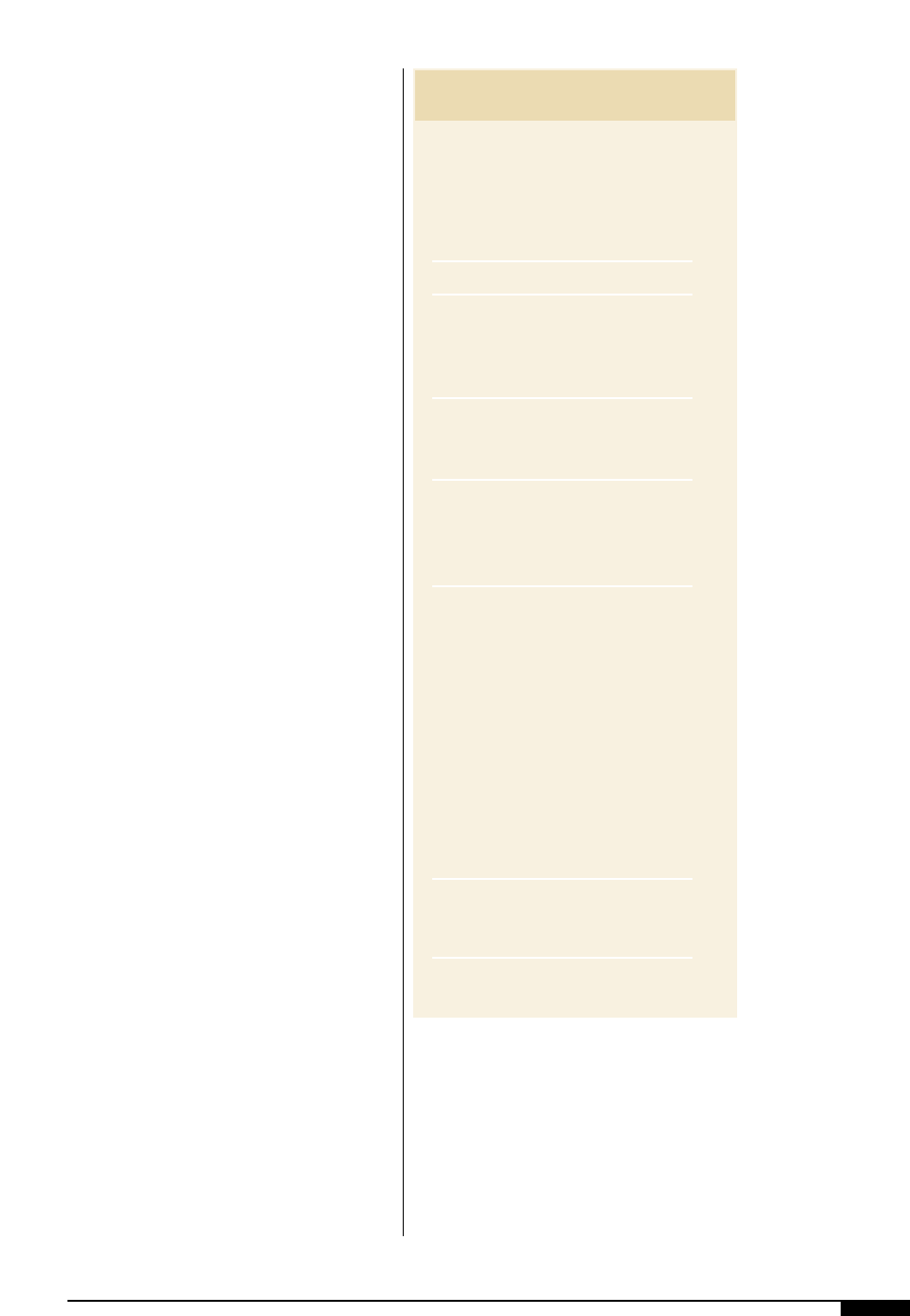

2@

For good decorative

printing, the absence

of “plate breaks” is

mandatory. Seamless

pattern printing is the

most obvious feature

and is the principle

reason for using laser-

engraved design-roll

cylinders.

2@

Table 8

ADVANTAGES

■ No film production

■ No light scatter during exposure

■ Excellent tone reproduction

DISADVANTAGES

■ Increased plate costs (due to no liquid

polymer reclaim in nonimage areas)

■ Slower plate turnaround

■ High cost of the laser-imaging units

LASER ABLATION OF LIQUID PHOTOPOLYMERS

Table 9

■ Seams between plate units would show

objectionable breaks in a continuous pattern

design

■ The nature of the design demands intricate

plate mounting with a large number of small

repeats

■ Close register is required.

■ Plates will be used over a long period and be

subject to numerous washups

■ Repeat orders necessitate plates be on and

off the press over a period of time

CONSIDERATIONS FOR

DESIGN ROLL USE

conventional flexographic printing plates

might be mounted. Design rolls can be man-

ufactured for most cylinder sizes, from small

narrow-web cylinders to the very large wide-

web types.

The thickness of rubber or photopolymer

plate compound, applied during manufac-

ture of the design roll, is typically 0.125" or

greater. This makes a standard plate-mount

cylinder, undercut from the gear pitch diam-

eter to allow 0.125" or more of combined

plate and stickyback, ideal for laser-

engraved design roll application.

Vulcanized Rubber

Compound Selection

For vulcanized laser-engraved design rolls,

a range of natural rubber, synthetic rubber

and polymer compounds are available. Some

of these, however, are not usable for the

molded-plate applications. The printer may

specify a rubber compound for mounted-

plate operations, or depend upon the exper-

tise of the laser engraver to recommend the

best compound for the environment in which

the roll will be used. Characteristics to con-

sider when choosing the best rubber cover-

ing for the printing process include ink and

solvent exposure, press speed, ambient tem-

perature, substrate to be printed and run

lengths.

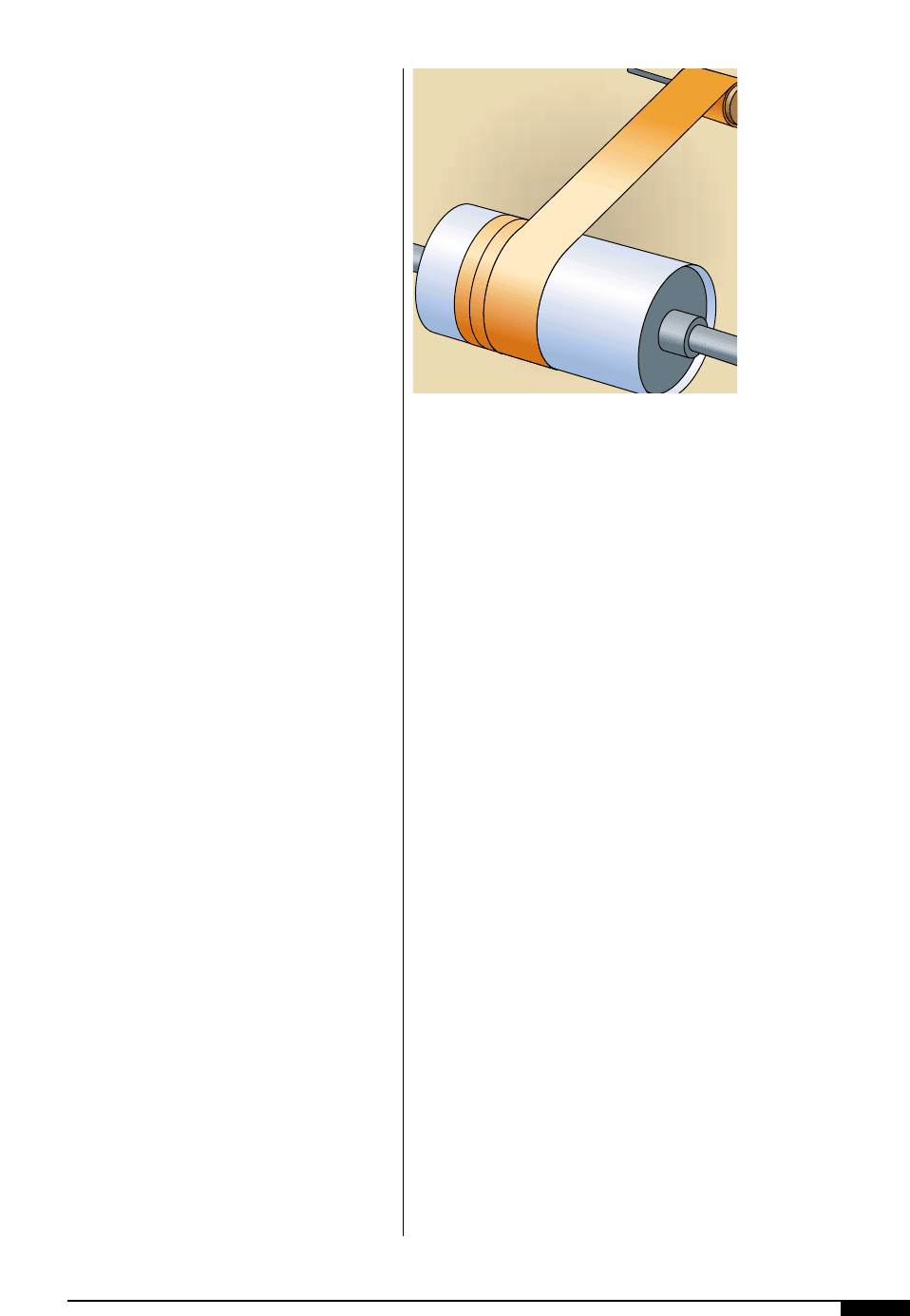

Compound Application

Before the application of the compound,

the surface of the cylinder is coated with a

suitable adhesive to ensure bonding during

vulcanization. Usually, thin, latex-like, sheets

of the chosen compound are wrapped

around the cylinder or sleeve under tension

and pressure to ensure that no air is trapped

between the successive layers (Figure

2#

).

Excess compound is applied to allow for

shrinkage during the subsequent vulcaniza-

tion process and to allow for grinding to size.

The wrapped compound is then tightly

wound with wet shrink tape, and end plates

are applied to prevent the compound from

escaping during the vulcanizing process.

Vulcanizing

The wrapped roll is placed in an autoclave,

where, under elevated temperature and

pressure, it is “cooked” until the compound

is vulcanized (fused) to form a solid sleeve

that is firmly bonded to the cylinder base.

Vulcanizing time will vary relative to roll size

and compound thickness.

Photopolymer Application

Strippable sheet photopolymer may also

be used to coat the print cylinder to form a

print surface for a laser-engraved design roll.

Raw (uncured) sheet photopolymer is first

stripped from the polyester backing material

and applied to the surface of the print cylin-

der. When sufficient photopolymer has been

applied to the surface of the cylinder, it is

fully cured using high energy ultraviolet light

before grinding and polishing.

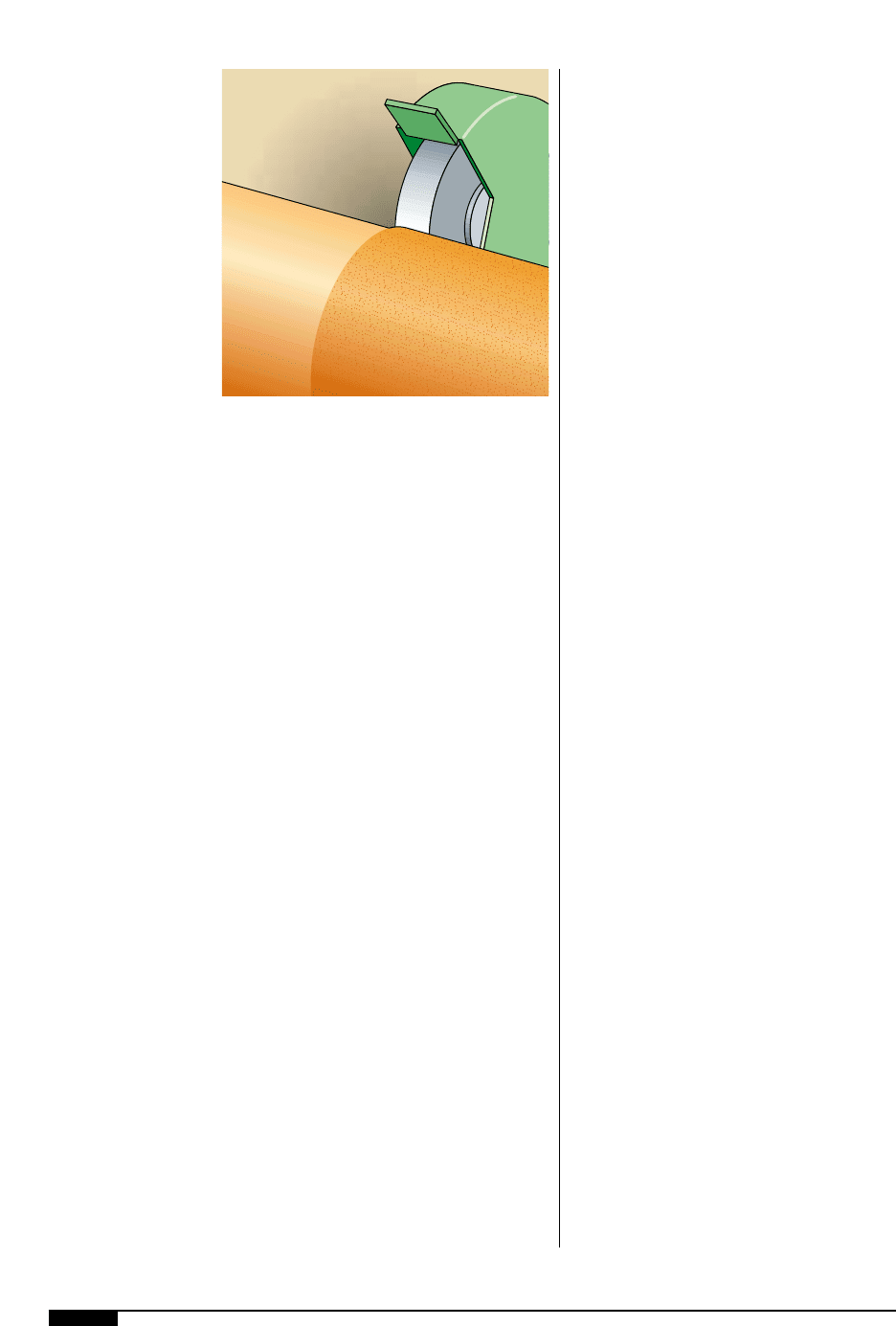

Grinding and Polishing

A vulcanized roll must be allowed to

“cook” for up to 24 hours to stabilize the

compound before it can be cooled and

rough-ground to remove excess rubber

(Figure

2$

). Up to four more days must

elapse before final grinding and polishing

PLATES 39

2#

2#

Thin, latex-like sheet of

rubber or photopolymer

is wrapped around the

cylinder or sleeve.

Tension, or pressure,

is applied to ensure

that no air is trapped

between the layers.

40 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

can take place. The objective is to produce a

stress-free roll that is dimensionally stable,

concentric and smooth within a dimensional

tolerance of 0.001".

One advantage of using photopolymer is

that cured photopolymer is more dimension-

ally stable and may be ground to the final

diameter without the aging or seasoning

delay. This also applies to polyurethane cov-

erings.

Polyurethane Covering

In certain flexographic applications, par-

ticularly those requiring a high order of

resistance to wear and damage, cylinders

are covered with cast polyurethane, selected

for laser compatibility, ink transfer and

toughness. These cylinders are finished and

sized in the same way as rubber.

PREPARING ARTWORK

FOR DESIGN ROLLS

The cylinder surface of a design roll is

dimensionally stable and seamless; there-

fore, the stretching and shrinkage factors

associated with conventionally produced

plates, need not be considered when provid-

ing artwork for laser engraving. The ideal

input for laser-engraved rolls is one-up,

uncompensated digital graphics. Hard-copy

art, or undistorted positive or negative films,

may be used, but then need to be scanned

and digitized before they can be utilized for

laser engraving.

Digital artwork can be modified, stepped-

and-repeated, or otherwise layed out to meet

the requirements of repeat length (cylinder

circumference) and print width for the par-

ticular job. Digital artwork can also offer

specified trap between colors, provide bleed

and precisely place registration marks, eye

spots or other devices as part of the design.

Digital-proof prints may be produced direct-

ly from the electronic file or color keys and

glossy proofs can be made from convention-

al image-set films for review and approval of

the design before actual engraving is under-

taken. The final digital graphic files will then

be used to drive the laser output. Refer to

Table 9 for a summary on the use of design

rolls.

Engraving the Cylinder

While there are at least two different laser-

engraving technologies in use, each differing

in the way the laser beam is guided, both

achieve the desired result by using the con-

centrated high energy of the laser to remove

the plate material from the nonprinting areas.

The plate material, whether rubber, poly-

urethane or cured photopolymer, is vaporized

by the laser, leaving a clearly defined image.

Depending on the technology used and the

requirements of the specific application,

engraving depth can be varied from cylinder

to cylinder and the image shoulder profile

may be vertical, sloped or stepped.

Proofing and Inspection

The laser-engraved design roll can be

proofed on any one of several proofing

machines to check print uniformity with

minimum pressure. Proofs can also be made

to assist in mounting plates on other rolls to

be used in conjunction with the laser-imaged

design roll. The cylinder print surface and

2$

Excess rubber from the

vulcanized roll is rough-

grounded to produce a

dimensionally stable,

concentric and smooth

roll.

2$

images, as well as its mechanical compo-

nents, are inspected using special lighting

and magnification.

SPECIAL CARE CONSIDERATIONS

Unlike mountable printing plates, design

rolls are solid integral units, which cannot

easily be repaired or replaced if damaged.

With proper use and care, they are suitable

for long, or repeated, pressruns.

On press, cylinders should be exposed to

the minimum pressure consistent with qual-

ity printing. As the cylinders warm up on the

press, they may expand and print pressure

should be further reduced. As soon as a run

is completed, the cylinders should immedi-

ately be removed from the press and

cleaned. A cylinder can be cleaned quickly

and without damage using ample quantities

of cleaning agents designed for that purpose,

together with a soft-bristle brush.

All polymers and rubber compounds tend

to age and suffer changes in their physical

properties over time, especially if exposed

to elevated temperature, ozone or fluores-

cent light. If the cylinder is to be used again,

it should be stored in a cool area, suspended

by its journals, or by a rod through the bore.

It should be loosely wrapped to allow any

cleaning solutions it may contain to evapo-

rate, while protecting it from direct fluores-

cent light or sunlight.

Most electrical equipment, especially elec-

tric motors, produce ozone that may attack

rubber compounds and photopolymers.

Therefore, cylinders should not be stored

near such equipment. These precautions

also apply to standard plate-mounted cylin-

ders or plates being saved for future use.

DIRECT-TO-PLATE IMAGING

The newest technology to enter the flexo-

graphic printing plate market utilizes direct-

to-plate (DTP) or computer-to-plate (CTP)

imaging. These technologies are following

the trend in the general printing industry

toward film-less platemaking. Table 10 sum-

marizes some of the advantages and disad-

vantages of the direct-to-plate process.

In a conventional platemaking process,

the digital images in the graphics computer

are raster image processed or RIPped to the

emulsion of a photographic film to form a

negative image. The negative film is then

placed on the photopolymer with the emul-

sion in contact with the print surface of the

plate to be imaged. In all cases, there is a

thin “slip-film” on the surface of the pho-

topolymer to prevent the negative film from

sticking to the polymer during the exposure.

This slip-film proves detrimental and con-

tributes to image spread during plate expo-

sure, creating the shoulder on the relief char-

acters that is typical of a flexographic print-

ing plate. The supporting shoulders evident

in the relieved areas of a photopolymer

plate, are the result of light scattering within

the photopolymer. A conventionally imaged

(with film) plate is exposed in a contact

frame, where atmospheric gases, including

oxygen, are evacuated from the area imme-

diately surrounding the plate. This oxygen-

deprived environment contributes to the

development of the sharp transition from

printing surface to shoulder. As the plate is

impressed onto the substrate during print-

ing, the shoulder on the image causes the

print element to gain in size, creating the

“halo” that typifies flexographic printing.

With direct-imaged printing plates, the dig-

ital image in the graphics computer is RIPped

directly to a masking material that is an inte-

gral part of the print surface on the pho-

topolymer (Figure

2%

). The masking mater-

ial is burned away or ablated by a focused

laser beam. Once the mask is ablated with

eth RIPped date and a negative image crat-

ed, the plate is handled as a conventional

photopolymer plate. The one exception is

that during the exposure step, no vacuum is

PLATES 41

42 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

required, as the image-carrying mask is

alrady in intimate contact with the polymer

surface. There are, therefore, no materials to

interfere with the imaging light as it impacts

the plate surface. More importantly, expo-

sure and polymerization take place in the

presence of oxygen, which inhibits polymer-

ization at the plate surface. As a result, the

images that form in the plate are actually

smaller than the image that was written into

the integral mask; the shoulder is not as

sharp when compared to a conventionally

made plate imaged from the same electronic

file. This is an important factor when printing

highlight dots in halftone process screens

and stochastic images. Figure

2^

and

2&

show the enlarged dot structure of the same

highlight dot exposed conventionally and

digitally. While the digital difference is most

apparent in highlights, the full tonal range or

an image is affected.

The use of direct-to-plate imaging affects

more than just the platemaking step of the

flexo process. No film negative is generated

to make the plate, and consequently, no film

negative is available to make a proof. The

entire workflow right up to the press is now

digital. Color management and digital proof-

ing become essential elements of the

process. Some of these required technolo-

gies, in turn, will continue to improve, as

more of the process becomes digital. Digital

proofing, for example, has been available for

some time, yet, there is still reluctance to

accept these proofs as contract proofs.

Doubtless, continued progress will be made

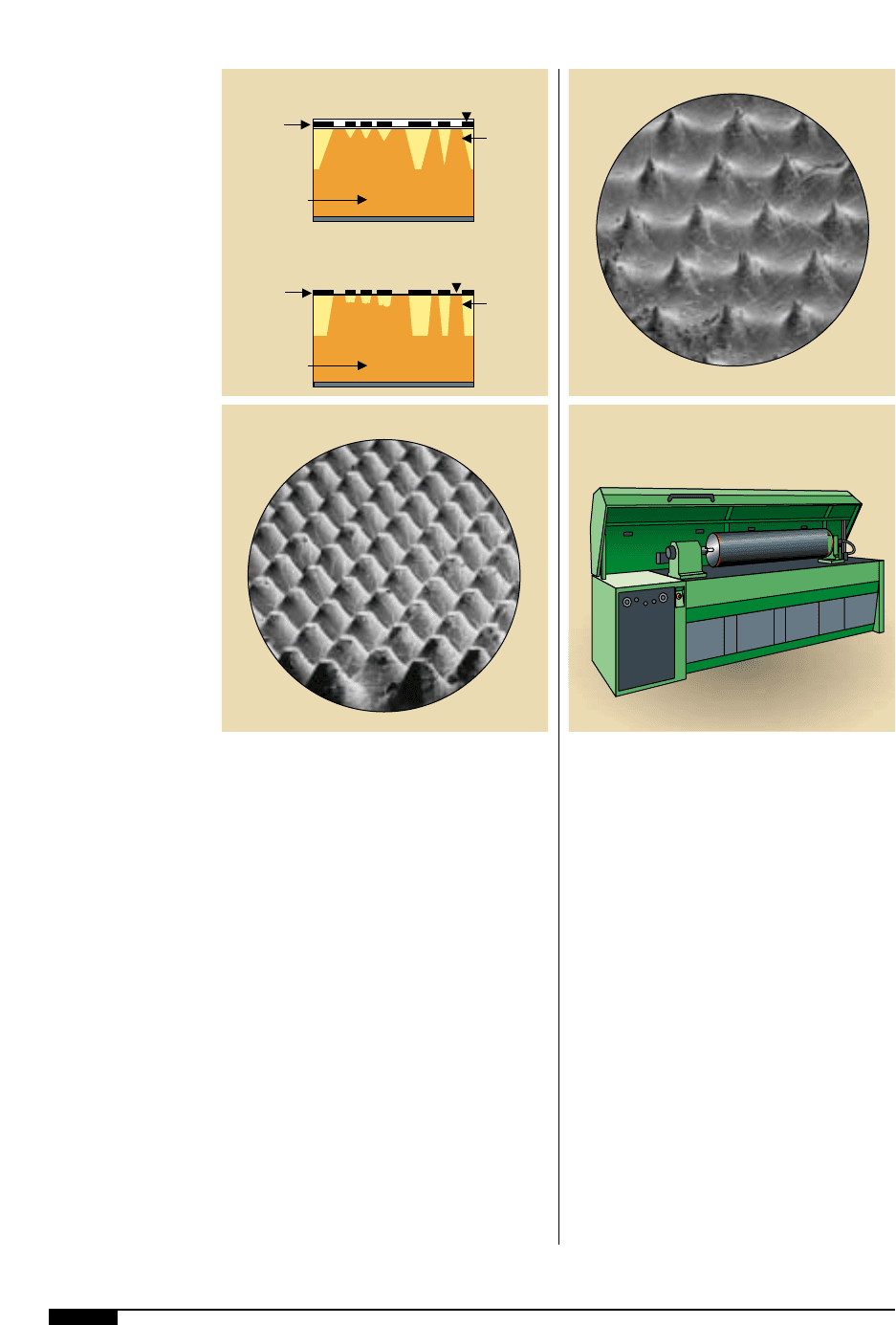

2%

Cross-sections of a

conventional and direct-

imaged plate reveals the

steeper shoulders of the

digital process.

2^

An enlarged detail of

a hightlight dot on a

conventional photo-

polymer plate.

2&

An enlargement show-

ing a highlight dot on

a digitally imaged pho-

topolymer plate.

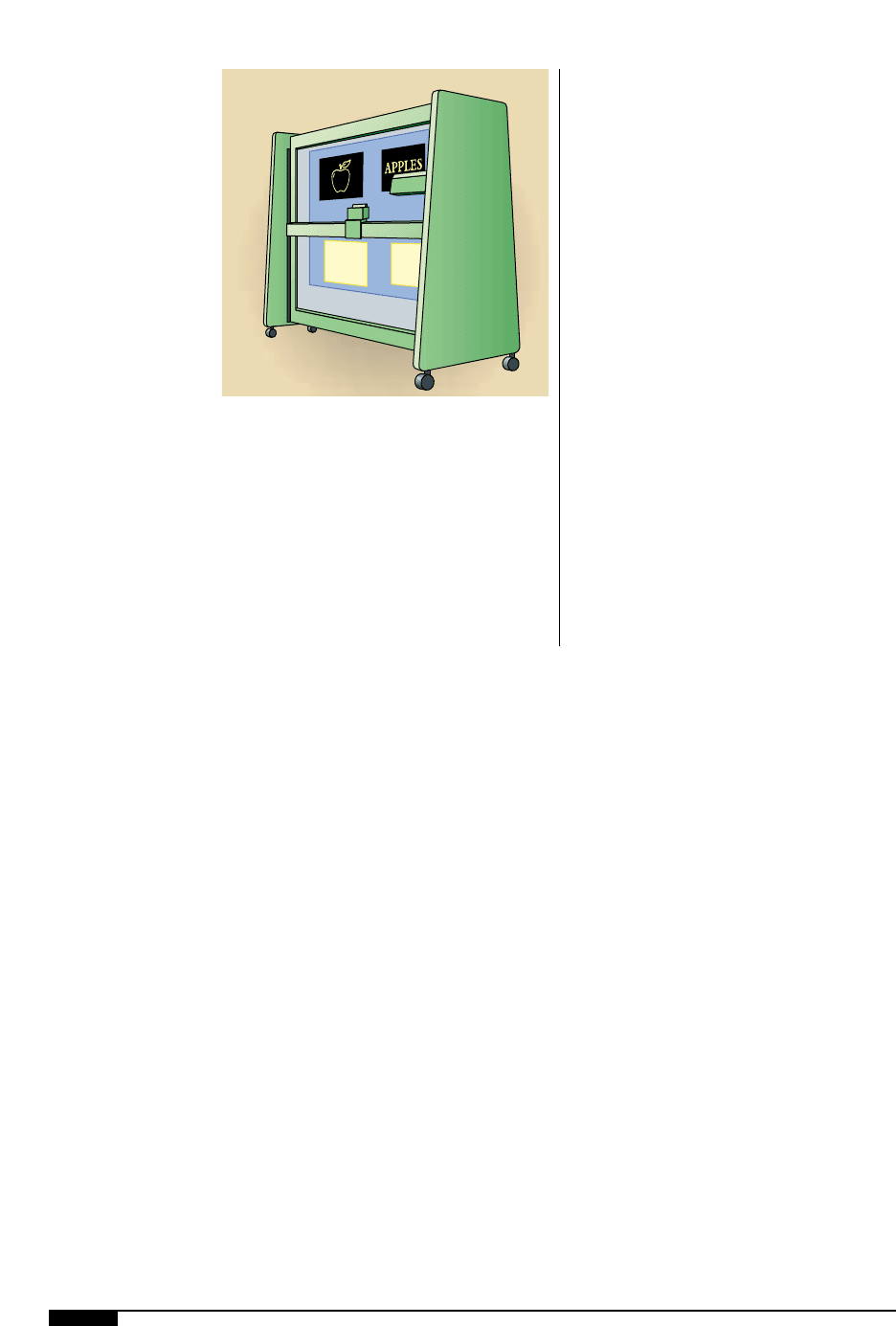

2*

The direct-to-plate

imager uses a laser

beam to ablate or vapor-

ize masking material on

the photopolymer plate

that is mounted on the

drum.

Negative Emulsion

Conventional Imaging

Slip Film

Photopolymer

Image

Shoulder

Direct-to-Plate Imaging

Ablated Image

Mask

Layer

Photopolymer

Image

Shoulder

2%

2^

2&

2*

in this area so that a completely digital work-

flow is possible. Process control and consis-

tency have always been required for quality

printing. New methods, tools, skills and

training are required for successful imple-

mentation of direct-to-plate.

Integral Mask Technology

This technology utilizes sheet photopoly-

mer, as well as in-the-round photopolymer,

bonded to sleeve, sized to fit typical plate

cylinders. The basic concept of this CTP

technology is to build a “mask” onto the

image surface of the raw plate material dur-

ing manufacture of the sheet or after surface

preparation of sleeved photopolymer. The

mask is a thin layer of material that blocks

ultraviolet light. The integrated mask mate-

rial on the plate is imaged by a laser that

ablates only the masking material in the

image areas of the plate. The laser imaging

equipment (Figure

2*

) is similar, in concept,

to that used to image offset printing plates,

laser imaged films, laser engraved rubber

cylinders and some rotogravure cylinders.

Note: In most equipment, the sheet pho-

topolymer is mounted on a drum for laser

ablation. If the exposure drum is of a dif-

ferent diameter than the print cylinder,

care must be taken to correctly calculate the

distortion compensation required. Also, the

exposure system may impose on the drum

in order to use all of the plate material. If

any images are rotated in order to fit effi-

ciently, compensation will need to be made

on a per-image basis, not globally. If done

globally, the compensation on the rotated

images would be incorrect. The supplier of

the imaging equipment should be consulted

for proper handling of the issue.

Ink-jet Mask Technology

The ultraviolet-blocking mask is generat-

ed on the surface the photopolymer of the

sheet photopolymer using ink-jet technolo-

gy (Figure

2(

). This DTP system is espe-

cially advantageous in the corrugated post

print sector, where many small pieces of

plate are generally mounted flat on a large

single carrier sheet. In this application, indi-

vidual pieces of sheet photopolymer are cut

roughly to the size of the image elements in

PLATES 43

Table 10

ADVANTAGES

■

All digital workflow eases implemen-

tation of color management and aids

in consistent, predictable image and

copy reproduction

■

Superior color registration is attained

■

No film is needed, resulting in saving

of the cost of film as well as the film

production, handling and storage

costs

■

Step and repeat can be incorporated

into the RIP, reducing file sizes and

speeding up output time

■

Vacuum is not needed during plate

exposure. Imaging faults caused by

air and dust trapped between the neg-

ative and plate are reduced

■

Intimate contact of mask on the plate

during exposure produces a sharper,

high definition plate image and

improves retained tone values, partic-

ularly in the highlights. Dot gain is

minimiezed throughout the entire

tonal range

DISADVANTAGES

■ Higher plate costs during initial

adoption of this technology

■ Learning curve of a new process

requires training on new equipment

and processes

■ High costs of the imaging units

DIRECT-TO-PLATE (CTP)

44 FLEXOGRAPHY: PRINCIPLES & PRACTICES

the design. The pieces of plate are mount-

ed in position on the large carrier sheet that

will be used on the press. The ultraviolet

blocking mask is then printed on the sur-

face of the individual plate pieces.

The fully computerized system reduces

overall plate production and mounting times

by as much as 30%, while dramatically

reducing plate material waste. The inherent

positional accuracy obtained when produc-

ing multicolor images, without the time-con-

suming mounting process, combined with

the material cost saving, more than offsets

the imaging cost.

The fully computerized system reduces

overall plate production and mounting times

by as much as 30%, while dramatically

reducing plate-material waste. The inherent

positional accuracy, obtained when produc-

ing multicolor images without the time con-

suming mounting process, together with the

material cost saving, more than offsets the

imaging cost.

Exposure and Processing of

Direct-imaged Plates

In both direct-imaging processes (integral

mask technology, ink-jet mask technology),

the plate is exposed on a standard platemak-

ing exposure unit, and processed in the nor-

mal fashion.

2(

The ink-jet mask imager

uses an ink-jet to create a

UV-blocking mask on the

surface of the photopoly-

mer.

2(