Fleet K. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 1, Byzantium to Turkey, 1071-1453

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

howard crane

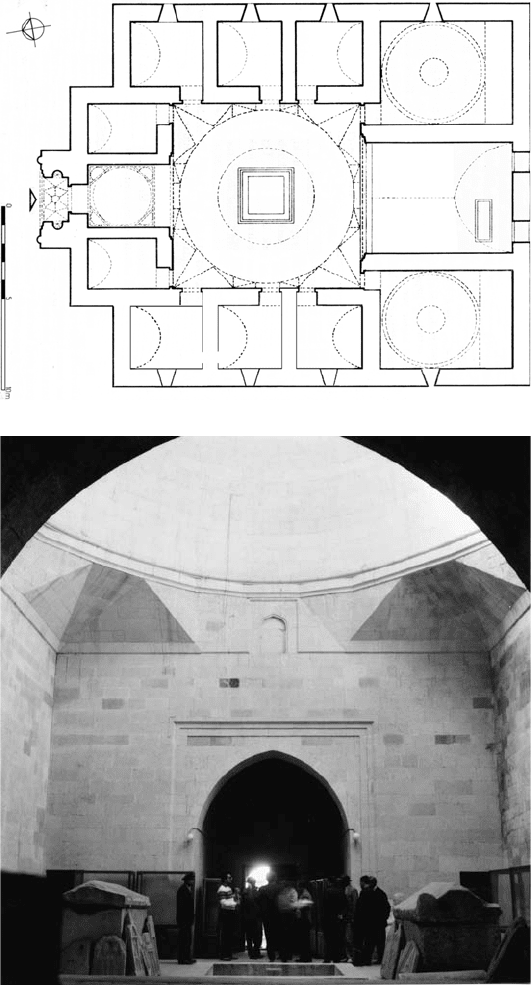

The Yakutiye in particular, with its fine, relief-carved portal, its fac¸ade origi-

nally flanked by a pair of brick minarets, and domed mausoleum at the back

is reflective of the nearby C¸ ifte Minareli Medrese dating to the mid-thirteenth

century. Beylikperiod closed court medreses in central Anatolia are rather closer

to the Konya tradition, with hemispherically domed courtyards recalling the

Karatay (649/1251–2) and

˙

Ince Minareli (c.1265) medreses. Two such buildings

were formerly found in Karaman. The first, the no longer extant Emir Musa

Medresesi, was founded by Karamano

˘

glu Musa Pas¸a and dated to the middle

years of the fourteenth century, while the second, identified by its foundation

inscription as an imaret, though in form belonging to the closed court medrese

type, was built by Karamano

˘

glu

˙

Ibrahim Bey in 836/1432. A third closed court

medrese of the Konya type dating to the early beylik period is the Vacidiye

Medresesi in K

¨

utahya (Fig. 8.12), in the principality of Germiyan. Local tradi-

tion holds the Vacidiye Medresesi to have been an observatory and connects

it with a certain ‘Abd al-Wajid ibn Muhammad (d. 1434), a Khurasani authority

on the religious and secular sciences, who is said to have settled in K

¨

utahya

during the reign of the Germiyanid ruler S

¨

uleyman S¸ah(1363–87). The founda-

tion inscription on its portal, however, states that it was founded as a medrese

in 714/1314 by one of the Germiyano

˘

glu emirs, Yakub Bey I, Mubarizeddin

Umur Savci, whose daughter was the mother of Yakub Bey II, using the cizye

(poll-tax on non-Muslims) of Alas¸ehir.

20

Constructed of drafted sandstone, the

medrese has in recent years been extensively restored. It is, nonetheless, clear

that its plan was originally strictly symmetrical. The main fac¸ade has a three-

tier arrangement with a rather simple but strongly projecting portal on the

medrese’s longitudinal axis. An entrance hall, covered by a dome on squinches

and flanked by a pair of small, barrel-vaulted rooms, gives access to the central

courtyard covered by a 9.5 metre dome on Turkish triangles with a large ocu-

lus. A square pool occupies the centre of the courtyard, which is flanked on

either side by three barrel-vaulted student rooms. At the back of the medrese,

following an oft-repeated formula, a raised eyvan covered by a pointed barrel

vault is flanked symmetrically by a further pair of domed rooms. Although

the eyvan must originally have functioned as a classroom, it today contains

a cenotaph (sanduka) said to be that of Molla Vacid (d. 1434), who served as

m

¨

uderris (teacher) of the medrese. Whether either of the rooms flanking the

eyvan originally functioned as the mausoleum of the founder, Mubarizeddın

Umur, is uncertain; no trace of a cenotaph can be seen in either. Overall, the

medrese presents a rather plain and unadorned appearance, with relief-carved

20 RCEA, 5346.

300

(a)

(b)

Figure 8.12 (a, b) Vacidiye Medresesi, K

¨

utahya, plan (Bo

˘

gazic¸i University, Aptullah Kuran

Archive) and view of courtyard and eyvan (Photo Katharine Branning)

howard crane

decoration restricted to the portal and to a narrow frame around the eyvan.

Formally, however, it adheres closely to the closed court medrese tradition of

Konya and C¸ ay of the second half of the previous century.

21

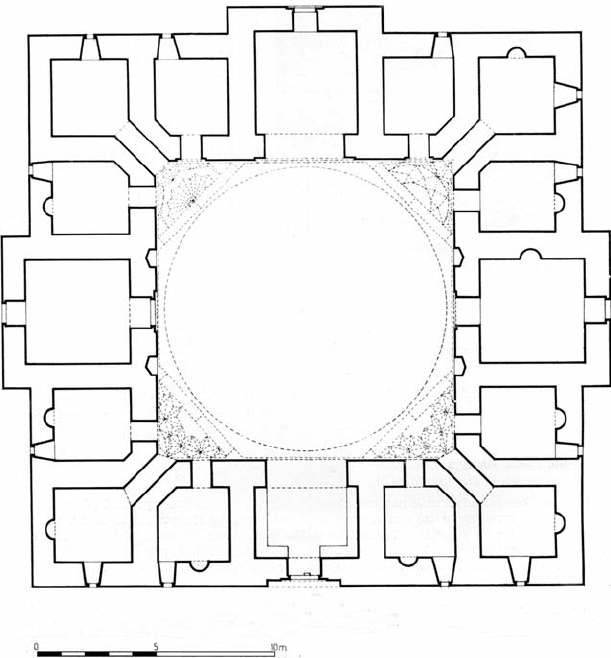

Closed court medreses are virtually unknown in the Turkoman principalities

of western Anatolia. A single Ottoman exceptionwould seem to be that of Hacı

Halil Pas¸a (the Haliliye Medresesi) (Fig. 8.13) in the town of G

¨

um

¨

us¸ some 25

kilometres from Merzifon. Built by Halil Pas¸a, the emir of G

¨

um

¨

us¸ Madeni who

was later made beylerbeyi in 1413 by C¸ elebi Mehmed, it is constructed of rubble

stone and brick and has a square plan with classrooms projecting from three of

the four sides. Although the central courtyard is today enclosed by an arcaded

portico carried on wooden columns, squinches filled with Turkish triangles

found beneath the portico make clear the fact that originally the courtyard was

covered by a dome measuring c.12.6 metres. Built, according to its inscriptions,

between 816/1413 and 818/1415, the medrese is unique in Ottoman architecture,

which favoured the open court medrese in the thirteenth-century tradition,

albeit with minor variations.

Although a number of medreses are recorded as having been built in Bursa,

˙

Iznik and Yenis¸ehir in the reigns of Orhan Gazi and Murad I, only a handful

survive, most notably the Lala S¸ahin Pas¸a Medresesi in Bursa, the S

¨

uleyman

Pas¸a Medresesi in

˙

Iznik, and the medrese in the second storey of Murad

H

¨

udavendigar’s imaret at C¸ ekirge. In all cases these are asymmetrical or anoma-

lous buildings, and it is not until the reign of Yıldırım Bayezid that open court

medreses of the type that was to become typical of Ottoman architecture are

attested. Frequently these are built as part of larger religious and social com-

plexes (k

¨

ulliye), as is the case with Yıldırım Bayezid’s medrese in his complex

in the eastern suburbs of Bursa completed in c.802/1399–1400. A long, nar-

row rectangular structure, it was entered through an eyvan in the main fac¸ade

covered by a dome atop a high, octagonal drum. The courtyard is enclosed

on three sides by porticos behind which were ranged student cells. A square

classroom, its floor two steps above the pavement of the courtyard, stood

21 The Hatuniye Medresesi is discussed in Diez et al., Karaman Devri Sanatı,pp.55–

66; Michael Meinecke, Fayencedekorationen seldschukischer Sakralbauten in Kleinasien

(T

¨

ubingen, 1976), pp. 165–70; Aptullah Kuran, ‘Karamanlı Medreseleri’, Vakıflar Der-

gisi 8 (1969), 216–17. For the Ermenak, Kayseri, Amasya and Aksaray medreses, see Kuran,

‘Karamanlı Medreseleri’; also Diez et al., Karaman Devri Sanatı,pp.20–4, 177; Gabriel,

MTA, i,pp.70–3; ii,pp.46–50. For the Yakutiye and Ahmediye medresesofErzurum,

see

¨

Unal, Erzurum,pp.32–57; the Emir Musa Medresesi and

˙

Ibrahim Bey

˙

Imareti are

discussed in Diez et al., Karaman Devri Sanatı,pp.50–4, 67–84; also Kuran, ‘Karamanlı,

Medreseleri’, pp. 211–12. For the Vacidiye Medresesi, see Sayılı, ‘The W

ˆ

ajidiyya Madrasa’;

also Metin S

¨

ozen, Anadolu Medreseleri, Selc¸uklu ve Beylikler Devri, 2 vols. (Istanbul, 1970–3),

ii,p

p.80–3.

302

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Figure 8.13 Haliliye Medresesi, G

¨

um

¨

us¸, Merzifon, plan

opposite the entrance and was again covered with a large dome atop a high

octagonal drum, mirroring the vaulting of the entry eyvan. Signs of a new

Ottoman architectural style include the abandonment of the exaggerated dec-

oration of the Seljuk gateways, the transformation of the classroom eyvan into

a square room open to the courtyard and covered by a domical vault, and, from

the exterior, the transformation of the block-like mass of the thirteenth- and

fourteenth-century medreses into a more articulated composition characterised

in its covering by a rhythmic sequence of domes and chimneys.

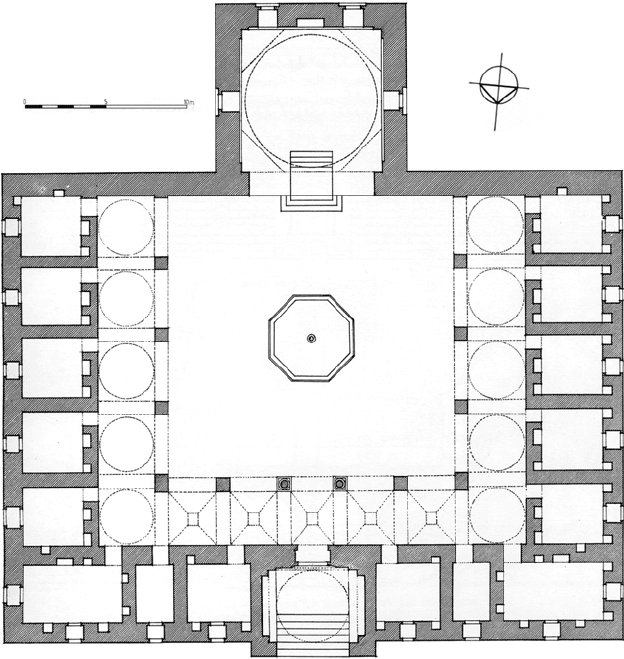

Of all surviving early Ottoman medreses, it is that of Bursa’s Muradiye com-

plex (Fig. 8.14) that is the most attractive both in its proportions and in its sober

and harmonious decoration. Situated immediately to the west of Murad II’s

303

howard crane

Figure 8.14 Muradiye Medresesi, Bursa, plan (after Gabriel, Une capitale turque,p.113)

mosque, the medrese is an Ottoman reworking of the traditional Anatolia open

court medrese plan. A classroom at the back projects on the exterior beyond

the south wall and opens on the north on to the rectangular central court-

yard, the other three sides of which are enclosed by domed and groin-vaulted

porticos. On the north a domed porch precedes the portal. Student cells dis-

tributed symmetrically along the east and west of the courtyard each contain

a fireplace and niches set into the walls for personal possessions. These, as

well as the service rooms ranged along the north side of the courtyard, are all

vaulted. The classroom, the floor of which is raised eight steps above the level

of the courtyard, is covered with a hemispheric dome on an octagonal drum

carried on muqarnas-filled pendentives. Although harmoniously proportioned,

304

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

the most striking and attractive aspect of the medrese is the ornamental treat-

ment of its masonry. Exterior and interior fac¸ades are for the most part con-

structed of alternating courses of brick and stone with more elaborate patterns

workedout above the courtyard porticos and on the fac¸ades of the gateway and

classroom. The nuanced and sober effect obtained through the utilisation of

simple brick and stone contrasts pleasingly with the colours of the octagonal,

turquoise-blue tiles used for the dado around the interior of the classroom.

22

Tombs

After mosques, it is commemorative architecture which is the single most

common building type in thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century Anatolia.

These monuments were founded for essentially two categories of individuals:

members of the ruling elite, that is, rulers, members of princely families, emirs

and high state officials; and revered religious figures, including popular saints

and, occasionally, honoured members of the ulema. Of the two groups, the

former is by far the better represented in terms of the number of standing

monuments, and is generally associated with the more outstanding examples

of tomb architecture as well. This should come as no surprise, given the fact

that it was the ruling elite who commanded the resourcesneeded for ambitious

architectural projects. It should be noted, however, that scale and elaboration

of surface treatment aside, in formal and planning terms, the mausolea built

by and for these two groups are essentially indistinguishable.

As in the Seljuk period, the tomb (t

¨

urbe, k

¨

unbed) architecture of the Turko-

man principalities, with a few notable exceptions which obstinately refuse to

fit any category, can be divided between the two basic types encountered in

Iranian commemorative architecture: the tower tomb and the domed square

or canopy tomb. Of the two, the tower tomb in its many variations is by far

the more common in beylik Anatolia and is even more varied than in the

Seljuk period. Nonetheless, the Anatolian Seljuk tradition is apparent in the

proportions of these buildings in that they tend to be far less lofty than is

the case with the tower tombs of the eastern Islamic world.

In both the beylik and early Ottoman periods, tomb architecture generally

retains its centralising and vertical character. As in thirteenth-century Anatolia,

mausolea consist of a cylindrical or polygonal shaft enclosing an uncompart-

mentalised room with one or more windows, entered through a single door.

22 For the G

¨

um

¨

us¸ Medrese, see Ayverdi, C¸SMD,pp.171–7, with photographs of the

squinches. For the medrese of Yıldırım Bayezid, see Gabriel, Une capitale turque,pp.73–4;

Ayverdi, OM

˙

ID,pp.447–54. For the Muradiye Medrese, see Gabriel, Une capitale turque,

pp. 112–14; Ayverdi, C¸SMD,pp.316–20.

305

howard crane

Although these rooms often contain symbolic sarcophagi or cenotaphs (san-

duka) and a mihrab, this is not unfailingly the case, suggesting that the main

function of this space is not in fact to house any particular object, but rather to

serve simply as an architectural interior. Generally, in beylik tombs the shaft

is covered by a conical or polyhedral cap, while in those of the early Ottoman

period, domical caps are more usual. Frequently, the shaft stands atop a square,

rectangular or polygonal crypt (mumyalık) covered with a barrel vault, groin

vault or dome, although such semi-subterranean chambers are not always

present. In many cases, their presence cannot be definitively ascertained short

of excavation, since frequently they do not have entrances. Where in fact a

mausoleum marks an actual burial site and is not simply a commemorative

cenotaph, the deceased is always interred in the ground, whether or not a

crypt is present, and never in the sanduka found on the raised floor of the

room within the tomb’s shaft.

Typologically, it is the form of the shaft that more than any other feature

servesto distinguish groupsof mausolea from one another. Thelargestnumber

of beylik tombs is polygonal in shape, most commonly octagonal, with pyrami-

dal roofs. Unelaborated examples include the tombs of Zincirkıran Mehmed

Pas¸a (779/1377) in Antalya, of Kalender Baba (c.1428) in Konya and the Hocendi

or B

¨

uy

¨

uk T

¨

urbe (c.1326) in Mut. In some instances monumental portals or

porches are added to the entry fac¸ade, as in the Ali Cafer T

¨

urbesi (c.1350)in

Kayseri, where this feature took the form of a small, enclosed vestibule, and the

Emin

¨

uddin T

¨

urbesi (c.1452) in Karaman, which had a domed porch supported

by columns. Perhaps the most spectacular of these octagonal tombs, one of

the most outstanding among Anatolian mausolea, is the t

¨

urbe of H

¨

udavend

Hatun in Ni

˘

gde (Fig. 8.15), the exterior surfaces of which are richly worked

in geometric, vegetal and zoomorphic relief. Situated atop a low, octagonal

base that may house a crypt, the tomb is covered by a pyramidal roof on the

exterior and a hemispheric dome in the interior. The tomb chamber is reached

by a double flight of three steps, and entered through an elaborately framed

gateway that is mirrored in the decoration of the mihrab within. The three win-

dows have pointed relieving arches above their lintels, the lunettes of which

are filled with openwork screens of vegetal arabesque flanked in the spandrels

by high-relief harpies, sphinxes and eagles. A dedicatory inscription identifies

the person for whom the tomb was built as one of the daughters of the late

Seljuk ruler R

¨

ukneddin Kılıc¸ Arslan IV, H

¨

udavend Hatun, who is thought to

have been the wife of a Mongol prince. Although the inscription states that

the tomb was erected in 712/1312–13, the inscription on her cenotaph informs

us that she did not die until 732/1331–2.

306

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Figure 8.15 H

¨

udavend Hatun T

¨

urbesi, Ni

˘

gde, general view (Photo Walter B. Denny)

While the largest number of polygonal funerary monuments of the beylik

period is octagonal in plan, there exist a small number of pentagonal, hexagonal

and dodecagonal tombs as well. These latter forms first make their appearance

in Anatolia in the period of the emirates. The Y

¨

ur

¨

uk Dede T

¨

urbesi (late four-

teenth century) in Ankara is a unique example of a pentagonal tomb, while

the hexagonal type is represented by the t

¨

urbe of Hızır Bey (mid-fourteenth

century) belonging to the Tas¸kın Pas¸a complex in Damsa K

¨

oy

¨

u,

¨

Urg

¨

up. The

dodecagonal plan is particularly associated with the Karakoyunlu in the region

around Lake Van. Examples include the tombs of Halime Hatun (760/1358–9)

in Gevas¸ and of Erzen Hatun (799/1396–7) in Ahlat. The mausoleum of Alaed-

din Bey in Karaman (c.1388) is the only example of this type in central Anatolia.

Funerary monuments with cylindrical shafts and conical caps are rather rare

as well. Their origins are to be found in the regions of Erzurum and Ahlat

and for the most part they date to the latter part of the thirteenth century.

307

howard crane

Beylik-period examples include the Sırc¸alı K

¨

umbet in Kayseri, an Eretnid tomb

of the mid-fourteenth century, and the unique Akkoyunlu tomb of Zeynel

Mirza (second half of the fifteenth century) at Hısn-i Keyf (Hasankeyf) on the

Tigris in south-east Anatolia. This latter, a Timurid-appearing structure, built

according to its inscription for Zeynel Bey, the son of Sultan Hasan Bahadur

Han (presumably Akkoyunlu Uzun Hasan), is constructed of brick with square

kufic renderings of the names of the Prophet and Rightly Guided Caliphs in

blue-green glazed brick on its shaft, and is covered by a bulbous, Timurid-style

dome.

Square tombs constitute a more complex and diversified group. The most

common type has a square base supporting an octagonal drum with prismatic

elements in the zone of transition resembling exposed squinches. Examples

include the Ilkhanid Nureddin ibn Sentimur T

¨

urbesi (713/1314) in Tokat and

the Karamanid tombs of Fakih Dede (860/1455–6) in Konya and of

˙

Ibrahim

Bey (868/1463–4) adjoining his imaret complex in Karaman. Far grander in

scale but similar in plan are the tomb of S¸eyh Hasan Bey, the emir of Eretna,

in Sivas, known as the G

¨

ud

¨

uk Minare (748/1347), with a system of exposed

Turkish triangles around the zone of transition and a cylindrical shaft and

conical roof, and those of Seyyid Mahmud Hayrani in Aks¸ehir and Celaleddin

Rumi in Konya. Both of the latter, though originally built in the Seljuk period,

were rebuilt in their present form by the Karamanid emirs in the early fifteenth

century and have great, fluted, cylindrical drums above square bases. Other

examples of this square type of tower tomb, such as the G

¨

undo

˘

gdu T

¨

urbesi

(745/1344)inNi

˘

gde, have square bases with bevelled upper corners forming

an octagon atop which is placed an octagonal drum. The most extraordinary

variant on the square type, however, is the tomb of the fourteenth-century

Turkish poet and mystic, As¸ik Pas¸a (d. 733/1333) in Kırs¸ehir (Fig. 8.16). Rectan-

gular in plan, it consists of a vaulted entry hall along one of the sides of the

tomb and a square tomb chamber covered by a hexagonal drum and dome

on pendentives. Entrance into the tomb chamber is through a door in one

of the long sides of the entry hall, requiring that the visitor turn through 90

degrees to pass from the entry hall into the tomb interior. It is the main fac¸ade

of the building that, even more than the plan, is the tomb’s most remarkable

aspect, however. Veneered in marble, it is dominated in the Seljuk manner

by a monumental portal projecting from the mausoleum’s north-west cor-

ner. Curiously, although harking back to thirteenth-century antecedents in its

composition, the portal is profoundly un-Seljuk in terms of the specific forms:

a frame relief carved knotting in place of geometric interlacing and central

niche headed by a fluted shell form in place of a muqarnas-filled semi-dome.

308

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Figure 8.16 As¸ık Pas¸a T

¨

urbesi, Kırs¸ehir, general view (Bo

˘

gazic¸i University,

Aptullah Kuran Archive)

The result is a tomb absolutely unique in the context of Anatolian Turkish

architecture.

In early Ottoman tomb architecture, in contrast to that of the other Turko-

man principalities, it is variations on the domed square rather than the tower

tomb that are most commonly encountered in the period before the middle

of the fifteenth century. Although a tomb said to be that of Ertu

˘

grul Gazi is

located in S

¨

o

˘

g

¨

ut, and those of Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi are located in the

Hisar in Bursa, all are late reconstructions of earlier buildings ordered by sul-

tans Abd

¨

ulaziz and Abd

¨

ulhamid II in the second half of the nineteenth century.

The earliest surviving Ottoman tombs do, nonetheless, date to the reign of

Orhan Gazi, and include those of Osman’s son C¸ oban Bey, in Bursa, of Lala

S¸ahin Pas¸a (c.749/1348) in Mustafakemalpas¸a (Kirmastı) and, in all likelihood,

the tomb known as the Kırgızlar T

¨

urbesi (mid-fourteenth century) in

˙

Iznik.

These last two are particularly interesting because of their unique plans: a

domed square tomb chamber preceded by a deep eyvan, an arrangement met

nowhere else in Turkish Anatolian architecture.

More typically, early Ottoman tombs are characterised by square tomb

chambers, frequently preceded by an open porch or small vestibule. Such,

for example, was the case with the tombs of Yıldırım Bayezid and G

¨

ulc¸ic¸ek

Hatun, the wife of Murad I and mother of Bayezid I. Bayezid’s tomb, one of

309