Fleet K. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 1, Byzantium to Turkey, 1071-1453

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

howard crane

Significant patronage was also provided by other members of the Ottoman

dynasty, including Orhan Gazi’s brothers Alaeddin Bey (d. 1331) and C¸ oban

Bey, and his son Gazi S

¨

uleyman Pas¸a; Murad I’s sons Yakub C¸ elebi and Yahs¸i

Bey; and Bayezid’s sons Ertu

˘

grul and Musa C¸ elebi. Similarly, royal women,

including Orhan’swife Nil

¨

ufer Hatun, G

¨

ulc¸ic¸ek Hatun (the wife of Murad I and

mother of Bayezid I), Devlet Hatun (d. 1414, the wife of Bayezid I and daughter

of Germiyano

˘

glu Yakub Bey, who was also the mother of Mehmed I), and

Hafsa Sultan and Selc¸uk Hatun (both daughters of Mehmed I) were important

patrons of architecture. Among the early Ottoman emiral families, it was the

C¸ andarlı who were the most outstanding builders through several generations

beginning with Halil Hayreddin Bey, followed by Ali Pas¸a,

˙

Ibrahim Pas¸a, Halil

Pas¸a and Mahmud C¸ elebi. Their most important foundations are located in

Bursa and

˙

Iznik. Likewise Kara Timurtas¸Pas¸a and his sons Oruc¸Bey,Umur

Bey and Ali Bey were noteworthy patrons of architecture in Bursa, Edirne,

K

¨

utahya, Dimetoka and Manisa. Several members of the ulema seem also to

have been important builders. They include the first Ottoman s¸eyh

¨

ulisl

ˆ

am,

S¸emseddin Mehmed Fenari (d. 1431), Hafuzeddin Mehmed Efendi (d. 1424),

the Hanifi jurist, and Amasyalı Sufi Bayezid, the tutor (lala) of Mehmed I.

Finally, a scattering of foundations can be identified as being the work of

members of the commercial and artisan classes, including the merchants Hacı

S¸ihabeddin, who foundedtheSeyyid Nasir Mescid and Zaviye(before 855/1451),

Hoca Sinan, who built the Boyacı Kulu K

¨

opr

¨

us

¨

u (before 836/1443) in Bursa,

and a Bezirgan Bedreddin, who built a caravansary near Denizli. As regards

architects and artisans, Hacı

˙

Ivaz Pas¸a, the architect of the C¸ elebi Mehmed

Camii in Dimetoka and the Yes¸il complex in Bursa (who was also for a time

Mehmed I’s grand vezir), built mosques in Ankara, Bursa and Tokat, while

Nakkas¸ Ali, the decorator of the Yes¸il Camii, built the mosque bearing his

name inside the Hisar in Bursa.

The arts

The arts of the century and a half between the beginning of the fourteenth and

the middle of the fifteenth century are very unevenly represented in the corpus

ofsurvivingartefacts,although a lack of objects is occasionally compensated for

to a degree by other sources. While a number of finely carved wood furnishings

and architectural fittings survive, and fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century

pottery and ceramic developments are fairly well understood from excavated

materials and the glazedtile decorationpreserved in situ in architectural monu-

ments, only a scattering of objects representative of the arts of the book

320

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

and of the textile arts have been preserved. Literary sources are of some help

in reconstructing a more complex picture of the silk industry than known and

dated objects might suggest, and scattered examples of manuscript illumina-

tion and architectural painting can be of some assistance in supplementing the

very limited picture of book illustration in the period that could be had from

the single known example that has come down to the present day. Metalwork

remains a little explored area concerning which there has been considerable

speculation in light of the number of significant objects in brass, bronze, steel

and precious metals that survive from the Seljuk period. It is likely, therefore,

that metalwork of artistic merit was produced in the beylik period, but until

now only a handful of dated objects, including a silver inlaid bowl in the Mam-

luk style inscribed with the name and titles of Murad II, today in the Hermitage

in St Petersburg (Hermitage nt 359), have been identified.

31

Painting

Only four illustrated manuscripts of diverse provenance, disparate content

and uneven quality survive from thirteenth-century Anatolia, far too few to

permit discussion of a school of Anatolian Seljuk book painting. Manuscript

illustration is even less well known with regard to the fourteenth and early

fifteenth centuries, and although rather unconvincing attempts have been

made to attribute a group of paintings in the Istanbul Albums depicting

demons, monsters, dervishes and nomads to eastern Anatolia,

32

in fact not

a single work can be attributed to the Turkoman emirates of the east. Liter-

ary sources refer to an atelier of painters at the Ottoman court in Edirne

in the second quarter of the fifteenth century and praise the skill of the

painter Husamzada Sunullah, but none of his work survives. An illumi-

nated double frontispiece dated 838/1434–5 and dedicated to Murad II in a

treatise on music, the Maqasid al-Alhan of Abd

¨

ulkadir b. Gaybi al-Maragi,

33

hints at the high quality of contemporary work at Edirne.

34

That the ate-

lier continued to function into the third quarter of the fifteenth century is

clear from the copy of the Dilsizname of Badieddin al-Tabrizi in Oxford,

35

31 See A. S. Melikian-Chirvani, Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, 8th–18th Centuries

(London, 1982), pp. 356–68; also J. S. Allan, ‘From Tabr

ˆ

ız to Siirt – Relocation of a

Thirteenth-Century Metalworking School’, Iran 16 (1978), 182–3.

32 See Bayhan Karama

˘

garali, ‘Anadolu’da XII–XVI Asırlardaki Tarikat ve Tekke Sanatı

Hakkında’, Ankara

¨

Universitesi

˙

Ilahiyat Fak

¨

ultesi Dergisi 21 (1976), 247–84.

33 Topkapı Sarayı, r 1726.

34 See Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, The Anatolian Civilizations, vol. III: Seljuk

and Ottoman (Istanbul, 1983), p. 107.

35 Bodleian Library, MS. Ouseley 133.

321

howard crane

the colophon of which states that the manuscript was produced at Edirne in

860/1455–6.

36

Only a single manuscript, a text of the

˙

Iskendername of Ahmedi, copied in

Amasya in 819/1416 (Fig. 8.19),

37

three years after the author’s death, serves

to document the existence of Ottoman book illustration prior to the reign of

Mehmed II. Although the manuscript is illustrated with twenty paintings, only

three of these (folios 117v, 295v and 296v) are actually painted on the pages of

the manuscript and so can be assumed to be contemporary with the copying of

the text. All seventeen of the remaining illustrations are cut from two earlier

manuscripts, one apparently with paintings in the mid-fourteenth century

Ilkhanid style associated with the so-called small format Shahnames and the

other in the Inju style of Shiraz. All the miniatures, both originals and those

pasted into the text, are in poor condition, so it is difficult to establish their

stylistic features. In terms of subject, the three original paintings depict groups

of gold-nimbed riders set on blue or green grounds speckled with gold dots.

Although Grube has seen a late Byzantine inspiration for these paintings,

their most striking quality is perhaps their sheer primitiveness and lack of

sophistication in terms of both composition and execution. The paintings do,

nonetheless, betoken a demand for illustrated manuscripts at Amasya during

the reign of C¸ elebi Mehmed, when the city enjoyed a considerable cultural

and political prestige, and attest to the presence there of a painter of at least

modest talent.

38

Although only three of the paintings in the Biblioth

`

eque Nationale

˙

Iskendername can be considered contemporary with the date given in its

colophon, those paintings reused from earlier manuscripts are nonetheless

enclosed in decorative frames of bold leafy and floral patterns characterised

by the same gold speckled backgrounds as the three original paintings, sug-

gesting that they are work of the same moment. It is interesting to note that

these framing compositions, examples of the art of illumination (tezhip), bear

a passing resemblance to some of the painted decoration in contemporary

architectural monuments. This latter, generally executed on dry plaster in a

kind of fresco a secco, is referred to generically as kalem is¸i, or brushwork paint-

ing. Although the technique must have been quite widely used in both beylik

36 Ivan Stchoukine, ‘Miniatures turques du temps de Mohammad II’, Ars Asiatiques 15

(1967), 47–50.

37 Biblioth

`

eque Nationale, suppl. Turc 309.

38 For Biblioth

`

eque Nationale, suppl. Turc 309, see Esin Atil, ‘Ottoman Miniature Painting

under Sultan Mehmed II’, Ars Orientalis 9 (1973), 103–20; also Ernst J. Grube, ‘Notes on

Ottoman Painting in the Fifteenth Century’, in Essays in Islamic Art and Architecture in

Honor of Katharina Otto-Dorn, ed. Abbas Daneshvari (Malibu, 1981), pp. 51–61.

322

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

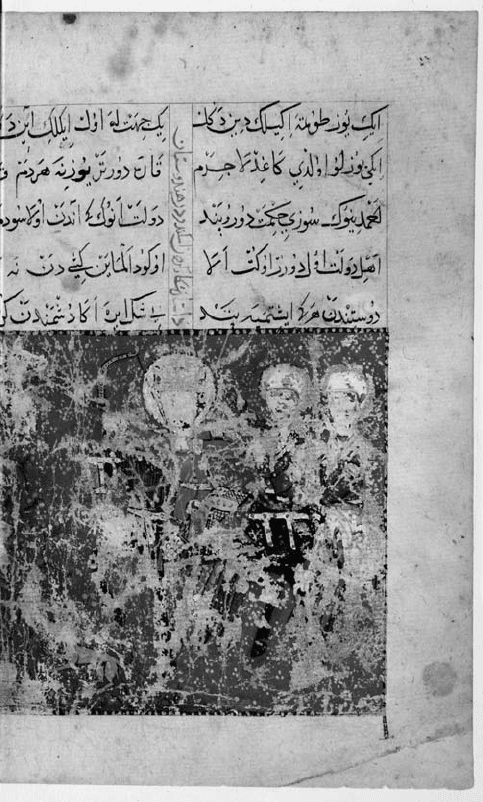

Figure 8.19

˙

Iskendername, dated 819/1416, Biblioth

`

eque Nationale de France,

suppl. Turc 309, folio 117v (courtesy Biblioth

`

eque Nationale de France, Paris)

and early Ottoman times, little of this work has survived the ravages of age

and damp or the restorer’s or whitewasher’s brush. Nonetheless, fragments

of such decorative programmes are still found in a number of fourteenth- and

early fifteenth-century buildings. The earliest surviving Ottoman examples are

in the drum of the dome of the mid-fourteenth-century Kırgızlar T

¨

urbesi in

323

howard crane

˙

Iznik. Coloured red, black, yellow and green, they depict not only such classic

motifs as arabesques of rumi leaves and blossoms on slender spiral stems, but

unfamiliar elements such as vases and columns as well.

With this single exception, all other surviving examples of early Ottoman

kalem is¸i would seem to pertain to the first half of the fifteenth century and

can in most cases be dated with considerable precision. Significant examples

have come to light in the Yes¸il Cami (822/1419–20 with work on decoration

continuinguntil 827/1424), as wellas in the tomb of S¸ehzadeAhmed (c.1430) and

the Hatuniye T

¨

urbesi (853/1449) in Bursa, in the Beylerbeyi Camii (832/1429)

and

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli Cami (847–51/1443–7) in Edirne, and in the Yahs¸i Bey Camii

(c.1440) in Tire. The finest surviving examples from the period, however, are

located in the prayer hall and fountain court of the Edirne Muradiye (839/1436).

Of the three painted layers, only the first can be dated to the period in question.

Its iconography includes naskhi, thuluth and kufic inscriptions set against leafy

arabesques and floral scrolls, ogival medallions filled with vegetal arabesques

set against dense floral backgrounds, a paradisiac garden of cypress trees and

flowering bushes on a flat ground (Fig. 8.20) and geometric interlace patterns

placed in a floral ground. Forms are outlined in black on a red ground and are

infilled in white, azure and yellow. That the paintings are contemporary with

the founding of the mosque is established by the fact that the blue underglaze

painted tiles of the prayer hall dado, which can be securely dated to the mid-

fifteenth century by the presence of analogous tiles in the mihrab, overlap the

painted decoration. Because so few examples of early kalem is¸i survive, it is

not possible to say much about its stylistic development in the early Ottoman

period. While later examples from the Classical period, such as the painted

decoration of the Selimiye Camii in Edirne (1569–74), resemble contemporary

textiles, earlier examples would seem to show a greater affinity to the art of

illumination.

39

Textiles

Although the production of luxury textiles in fourteenth- and early fifteenth-

century Anatolia is confirmed by numerous references in contemporary trav-

els, histories and documents, little survives from the time in the form of actual

woven fabrics. It is clear that silk production had for some time been associ-

ated with several places in Anatolia. In a well-known passage of his Travels,for

39 For kalem is¸i, see Elisabetta Gasparini, Le pitture murali della Muradiye de Edirne (Padua,

1985); Yıldız Demiriz, Osmanlı Mimarisi’nde S

¨

usleme, I, Erken Devir (1300–1453) (Istanbul,

1979), pp. 23–4, and under specific buildings.

324

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Figure 8.20 Detail, kalem is¸i, Muradiye, Edirne (Photo Walter B. Denny)

example, Marco Polo informs us that silk fabrics of crimson and other colours,

as well as many other kinds of cloth, were woven in Anatolia, and earlier

the Seljuk historian Karim al-Din Aqsara’i, in an enumeration of tribute gifts

sent from the Seljuk court in Konya to the Ilkhanid ruler in 1258, mentions

Antalya brocades (kamkha-i Antali).

40

Writing in the early fourteenth century,

al-‘Umari records that the principality of Akira (presumably Ankara) to the

south of Sinop, on the northern borderof the domains of Orhan Gazi, produced

large quantities of silk which was the equal of Byzantine brocade and cloth

of Constantinople.

41

Other sources imply that silks were produced in Aydın

in the early fourteenth century and that red silk stuffs were manufactured in

40 Marco Polo, The Book of Ser Marco Polo the Venetian Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of

the East, tr. and ed. Henry Yule (London, 1921), i,p.43; Karim al-Din Aqsara’i, M

¨

us

¯

ameret

¨

ul-ahb

¯

ar: Mo

˘

gollar Zamanında T

¨

urkiye Selc¸ukluları Tarih, ed. O. Turan (Ankara, 1944),

p. 62.

41 Al-‘Umari, Masalik al-absar, Al-‘Umari’s Bericht

¨

uber Anatolien, ed. F. Taeschner (Leipzig,

1929), p. 43.

325

howard crane

Alas¸ehir (Philadelphia), then still under Byzantine control, during the reign of

Murad I. Concerning more common textiles, Mustaufi states that cotton was

produced in Sivas, Ankara, Erzincan, Konya and Malatya,

42

and Ibn Battuta

takes note of an unparalleled cotton cloth with borders of gold, renowned for

the strength of its weaving and the quality of its cotton, named for the town

of Ladik (the ancient Laodicea) in the upper reaches of the Menander near

Denizli.

43

Just when the silk industry was established in Bursa is uncertain, although it

seems clear from the fact that Orhan Gazi built a bezzazistan (drapers’ market)

in his capital in the middle of the fourteenth century that the textile trade

must already have been of some importance. Such was certainly the case

when Bertrandon de la Broqui

`

ere passed through the city in 1432, for he notes

that all sorts of silk materials as well as cotton stuffs were for sale in the bazaar

of Bursa, although he does not state that the silks were actually produced

locally. That the manufacture of silk textiles was already established in Bursa

by the end of the fourteenth century, and its products were being exported to

Europe, is confirmed by Schiltberger, who compares the city’s silk trade and

industry with that of Damascus and Caffa and adds that its products were sent

from there to Venice and Lucca.

44

The raw silk used in the local manufacture of luxury textiles was not pro-

duced in Bursa itself, but was imported from the districts of Gilan and Mazan-

daran, south of the Caspian Sea in Iran. From there it was transported for

the most part overland via Tabriz, Erzurum, and Erzincan to Bursa, where

Persian traders established direct contacts with local and foreign merchants.

Because of the strong demand for silk brocades, velvets and satins, and because

the state treasury derived substantial revenues from the silk trade, it appears

that the Ottomans pursued a conscious policy of establishing Bursa as a major

entrep

ˆ

ot for Persian silk, and that this aim was at least in part the motivation

behind the extension of their political and military authority eastward in the

direction of Amasya, Tokat and Erzincan, and south toward Malatya, that is,

along the silk routes out of Iran.

45

42 Mustaufi, Geographical,pp.95, 98, 102.

43 Ibn Battuta, Travels, ii,p.425. 44 Schiltberger, Bondage and Travels,p.34.

45 Medieval literary references to textile production in Anatolia are collected by R. B.

Serjeant, in ‘Material for a History of Islamic Textiles up to the Mongol Conquest’, Ars

Islamica 15–16 (1951), pp. 57–9. The production of silks in Alas¸ehir is notedby As¸ıkpas¸azade,

Vom Hirtenzelt zur Hohen Pforte, tr. Richard F. Kreutel (Graz, Vienna and Cologne, 1959),

p. 87. For Aydın, see Pegolotti, Fr Balducci Pegolotti, La Pratica della Mercature, ed. A. Evans

(Cambridge, Mass., 1936), pp. 208, 297, 300;H.

˙

Inalcık, ‘Harir’, in The Encyclopaedia of

Islam, 2nd edn (Leiden, 1960–2006) [henceforth EI2], iii,pp.211–12. For Bertrandon de la

326

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Although tantalising references to the silk trade in fourteenth- and early

fifteenth-century Anatolia are to be found in the various literary sources, when

it comes to actual woven textiles,almost nothingsurvives whichcanbesecurely

attributed to the period. That this should be the case is at first glance, perhaps,

surprising, given the existence of the enormous collection of royal garments

and other textile pieces totalling some 2,500 items housed in the Topkapı

Museum in Istanbul. Comprising ceremonial garments and embroideries, the

collection had its origins in the Ottoman custom of bundling up the belongings

of a deceased ruler or prince and preserving them in the palace treasury.

Although this practice assured the preservation of these textiles, it in no way

guaranteed that a proper recording of their date and ownership would be kept.

Not surprisingly, inaccurate inventory lists, the mixing up of labels among

bundles at times of periodic inspection and the often speculative attributions

made by court officials resulted in a situation in which little reliance can be put

on the court records concerning these materials. Despite this, the Turkish art

historian Tahsin

¨

Oz, in a pioneering study of Turkish woven fabrics based on

this collection, attributedtothe fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries a group

of ten white cotton and silk kaftans, all with large floral patterns surrounded

by long serrated leaves in silk and silver thread. In the light of present research,

however, his attributions must be regarded as speculative at best.

To this questionable body of material there can be added a single silk bro-

cade, found today in the treasury of the twelfth-century monastery of Stu-

denica in Serbia, where it is held by popular tradition to have been the funeral

pall of the Serbian king Stefan Prvoven

ˇ

cani, donated by Olivera-Despina, the

younger daughter of the Serbian Prince Lazar, who was taken by Bayezid I as

his wife after the battle of Kosovo in 1389. The organisation of the textile into a

succession of stripes patterned alternately with geometric, floral and cloud

band motifs and bands of calligraphy is distinct from that of the vast majority

of later Ottoman textiles, but is frequently encountered in fourteenth-century

luxury fabrics from Persia, Egypt, North Africa and Spain. Two inscriptions in

thuluth on the pall repeat the invocations ‘the wise and just Sultan’ (al-sultan

al-‘alim al-‘adil) and ‘Sultan Bayezid Han, may his victory be glorious’ (Sultan

Bayazıd Han ‘azza nasruhu), and when interpreted in the context of both the

Broqui

`

ere’s comments, see Voyage d’Outremer, tr. Kline, p. 84; for Schiltberger, Bondage

and Travels,p.34. For the statement that by the end of the fourteenth century Bursa

already possessed an industry in silk fabrics, see

˙

Inalcık, ‘Harir’, EI2, iii,p.216. For the

Ottoman policy of promoting Bursa as a major entrep

ˆ

ot for Persian silk, see ibid.,p.212;

Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby,

˙

Ipek: The Crescent and the Rose: Imperial Ottoman Silks

and Velvets (London, 2001), pp. 155–9.

327

howard crane

historical and stylistic evidence, would appear to refer to the Ottoman Sultan

Bayezid I. Although several of the motifs, most notably the flowers and cloud

bands, derive from Chinese sources, and it is not impossible that the piece was

produced by Chinese weavers for a Near Eastern patronage, the late Richard

Ettinghausen argued persuasively that owing to its historical inscription, the

richness of its decoration and its royal connections, the Studenica silk must

be regarded as the outstanding example of late fourteenth-century Turkish

textile arts.

46

Carpets

As compared with contemporary Turkish textiles, carpet weaving in

fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century Anatolia is considerably better docu-

mented both by extant pieces and representations of carpets in contemporary

European painting.

47

That fine carpets were made in thirteenth-century

Anatolia is attested by Marco Polo (tepedi ottimi e li piu belli del mondo),

who passed through the region in 1271,

48

and by the Mamluk historian and

geographer Abu’l-Fida, who states on the authority of Ibn Sa‘id (d. 1274)

that Turkoman carpets were made in Aksaray.

49

Ibn Battuta, writing in the

early fourteenth century, confirms this remark, asserting that, ‘There are

manufactured there [in Aksaray] the rugs of sheep’s wool called after it, which

have no equal in any country and they are exported from it to Syria, Egypt,

Iraq, India, China and the lands of the Turks.’

50

In addition, Bertrandon de la

46 The kaftans in the Topkapı are numbered tks 414, 415, 416, 417, 418, 419, 4640, 4641,

4642 and 4463 and are discussed and illustrated by Tahsin

¨

Oz in Turkish Textiles and

Velvets: XIV–XVI Centuries,vol.I(Ankara,1950), pp. 23–4 and 45, and illustrated in Plates

I, II, IV. For a discussion of the Studenica pall, see Richard Ettinghausen, ‘An Early

Ottoman Textile’, First International Congress of Turkish Art, Communications (Ankara,

1961), pp. 134–43; Atasoy and Raby,

˙

Ipek,pp.240, 253–4.

47 For general accounts of early Turkish carpets, see Wilhelm von Bode and Ernst K

¨

uhnel,

Antique Rugs from the Near East, 4th edn, tr. Charles Grant Ellis (Ithaca, 1984); Kurt

Erdmann, The History of the Early Turkish Carpet, tr. Robert Pinner (London, 1977);

Erdmann, Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpets, ed. Hanna Erdmann, tr. May H. Beattie

and Hildegard Herzog (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1970); S¸erare Yetkin, Historical Turkish

Carpets (Istanbul, 1981). The Beys¸ehir carpets are discussed by Rudolf M. Riefstahl,

‘Primitive Rugs of the “Konya” Type in the Mosque of Beyshehir’, The Art Bulletin 13

(1931), 177–220; also Yanni Petsopoulos, ‘Beyshehir IX’, Halı 8 (1986), 56–8. For rugs from

Divri

˘

gi,

Charles

Grant Ellis, ‘The Rugs from the Great Mosque of Divrik’, Halı 1 (1978),

269–73. For the Anatolian animal carpets see C. J. Lamm, ‘The Marby Rug and Some

Other Fragments of Carpets Found in Egypt’, Svenska Orients

¨

allskapets Arsbok (1937),

51–130; Mackie, ‘An Early Animal Rug at the Metropolitan Museum’, Halı 12, 5 (1990),

pp. 154–5;S¸erare Yetkin, ‘Yeni Bulunan Hayvan Fig

¨

url

¨

u Halıların T

¨

urk Halı Sanatındaki

Yeri’, Sanat Tarih Yılıl

˘

gı [henceforth STY] 5 (1972–3), 291–307.

48 Marco Polo, The Book of Ser Marco Polo, i,p.46.

49 Abu’l-Fida’, Taqw

¯

ım al-Buld

¯

an, ed. T. Reinaud and M. de Slane (Paris, 1840), p. 379.

50 Ibn Battuta, Travels, ii,pp.432–3.

328

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Broqui

`

ere remarks that in 1432 he witnessed the way in which carpets were

woven while travelling near

˙

Iznik.

51

The so-called Konya-type carpets are widely accepted as being of thirteenth-

and early fourteenth-century date. Examples of this type were first discovered

by F. R. Martin in 1905 in the Alaeddin Camii in Konya. Additional fragments

were subsequently found by R. M. Riefstahl in the Es¸refo

˘

glu Camii in Beys¸ehir

and in Fustat (old Cairo), the latter confirming Ibn Sa‘id and Ibn Battuta’s

statements that Anatolian carpets were exported to Egypt. The Konya pieces,

three very large though damaged carpets and five smaller fragments, are all

today in the T

¨

urk ve

˙

Islam Eserleri M

¨

uzesi in Istanbul,

52

while two of the

Beys¸ehir pieces are in the Mevlana Museum in Konya and the third is divided

between the Keir Collection in London and a private collection in Germany.

Eight Fustat fragments of the Konya type are dispersed among the National-

museum in Stockholm, the R

¨

ohsska Konstsl

¨

ojdmuseum in G

¨

oteburg and the

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. On the whole, these carpets are

sufficiently well known as to require only some general comments. As a group

they are characterised by wide borders with monumental pseudo-kufic char-

acters or large stars, which contrast strongly with the field patterns composed

of single small geometric motifs arranged in staggered rows, some isolated and

others connected. The austerity of their design is reinforced by their sombre

colour scheme of five to eight tints, including a medium and a dark shade

of blue, a medium and dark red, yellow, ivory and dark brown. The carpets

are entirely of wool but are not very finely woven, having an average density

of seventy-seven symmetrical ‘Turkish’ knots to the square inch. Erdmann

noted that given the dimensions of the three damaged full carpets from the

Alaeddin Camii, the largest measuring some 2.85 by 5.50 metres, these could

not have been the products of nomad or village weavers, but must have been

done in urban workshops, since the looms on which they were woven had to

have been more than 2.5 meters in width. Just where these workshops were

located remains an unanswered question. Speculation as to whether these are

the products of some sort of court workshop is inconclusive, though there

is every reason to suppose that they were produced by weavers who catered

to the needs of the ruling elite. While their provenance is generally agreed

to be central Anatolia, the precise date of the Konya-type carpets remains

something of a mystery. Indeed, they have been placed anywhere from the

early thirteenth to the early fifteenth century. That rugs of this sort must

51 Bertrandon de la Broqui

`

ere, Le Voyage d’Outremer de Bertrandon de la Broqui

`

ere, ed. Ch.

Schefer (Paris, 1892), p. 86.

52 T

¨

urk ve

˙

Islam Eserleri M

¨

uzesi, 678, 681, 684, 685, 688, 689, 692/3.

329