Fleet K. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 1, Byzantium to Turkey, 1071-1453

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

howard crane

of technique, colour scheme and motifs, there is little to distinguish beylik-

period work from that of the thirteenth century. Other notable examples of

Seljuk-style cut tile used for beylik-period architectural decoration are the

interior of the dome of the tomb of Gazi Mehmed Bey (734/1334) at Birgi,

the pendentives of the mihrab bay of the

˙

Isa Bey Camii (776/1375) at Ayasoluk

and the mihrab of the Hasbey Dar

¨

ulhuffaz (824/1421) in Konya. Turquoise

or green glazed brick is worked into geometric patterns on the shafts of the

minarets of the Yakutiye Medresesi (710/1310–11) in Erzurum and the Ulu Cami

(778/1376) of Manisa, and on the drum of the G

¨

ud

¨

uk Minare (748/1347)inSivas.

On the whole, however, as compared with the glories of Seljuk architectural

faience of the previous century, the beylik period is one of scattered efforts

and decline, mirroring perhaps the diminished resources available for such

purposes.

The earliest Ottoman use of faience and glazed brick for architectural deco-

ration dates back to the end of the fourteenth century and is to be found on the

shaft of the minaret of the Yes¸il Cami (780–94/1378/9–91/2)in

˙

Iznik, which is

completely revetted with cut tile and glazed bricks. Despite the minaret’s catas-

trophic restoration using modern K

¨

utahya tiles in the early 1960s, it remains

clear that the

˙

Iznik minaret continues in the tradition of Seljuk glazed brick

and faience decorated minarets of the thirteenth century. Its shaft, covered

with a zigzag pattern of glazed bricks, is framed by borders of intersecting

octagons and braided and geometric star patterns, and is surmounted by a

balcony carried on moulded faience muqarnas. The dominant colour is green,

to which fact, obviously, the mosque’s name is to be attributed, but tiles of

turquoise, cobalt, purple and yellow were used as well.

Although monochrome tiles in turquoise and cobalt were used a few

years later in the decoration of the Yıldırım Bayezid’s mosque and hospi-

tal (c.793–802/1390–1399/1400) in Bursa, the most magnificent ensemble of

early Ottoman ceramic decoration is to be found in the mosque and tomb

of the Yes¸il complex (822–7/1419–24) of Mehmed I. Tile-revetted areas in the

mosque include the mihrab niche, dados around the main and side eyvans,

the

flanking tabhanes, the two mahfils at the back of the fountain court,

and the upper-storey imperial tribune (h

¨

unkar mahfili) and flanking ante-

chambers and balconies. In the case of the tomb, both exterior and interior are

enriched with faience decoration. On its exterior, broad expanses of turquoise

faience contrast dramatically with the epigraphic tympana above the windows

and the exuberant calligraphic and vegetal decoration of the portal niche

(Fig. 8.26), while the interior, dominated by a splendid faience mihrab,is

enriched as well by a turquoise dado with great arabesque medallions,

340

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Figure 8.26 Ye s¸il T

¨

urbe, Bursa, general view of exterior (Photo Walter B. Denny)

and a magnificent tiled cenotaph atop a high plinth (Fig. 8.27). The tiled

revetments of the Yes¸il complex are noteworthy not only for the scale on

which the work was carried out, but also for the range of techniques used in

the project. Indeed, three techniques can be identified. Twoof these, veneers of

monochrome glazed turquoise, green and blue tile and cut-tile faience mosaic,

hark back to the Seljuk tradition of ceramic architectural decoration of the

thirteenth century. To these, however, a new technique was added, one that

has its origins in Timurid Iran. Known as cuerda seca (‘dry cord’), it involved

the decoration of a single tile in glazes of several colours, a technique made

possible by outlining the design on the ceramic body in thin lines using a greasy

black pigment. Glazes of different colours applied within these contours were

thus prevented from running together.

341

howard crane

Figure 8.27 Mihrab and cenotaph (sanduka), Yes¸il T

¨

urbe, Bursa (Photo Walter B. Denny)

It is significant that the cuerda seca technique was unknown to either the

Seljuks or the Ottomans before the construction of the Yes¸il complex. As such

Mehmed’s foundation must be seen, not only in its scale and sumptuousness,

but also in terms of technology, as an important point of departure in the

history of Ottoman art. While cuerda seca tiles are not encountered in Anatolia

before this date, they had already, as early as the 1360s, been used in Timurid

Central Asia in the decoration of the tombs of the Shah-i Zinda in Samarkand,

where, after 1385, they were juxtaposed with work in cut-tile mosaic, possi-

bly introduced to the Timurid capital by craftsmen brought from what had

been Seljuk Anatolia and Ilkhanid Azerbaijan. The juxtaposition in Mehmed’s

foundation of cuerda seca tiles with ceramic techniques long established in

Anatolia thus suggests the involvement of craftsmen familiar with Timurid

tilework, a supposition confirmed by a Persian inscription on the mosque’s

mihrab identifying it as ‘The work of the Masters of Tabriz’.

Further evidence for the involvement of Persian craftsmen in the decoration

of the Yes¸il complex is to be found in a signature on one of the tomb’s wooden

doors, stating that it is ‘The work of Ali bin Hacı Ahmed of Tabriz’, and in

an inscription dated 827/1424 over the mosque’s imperial tribune containing

the name of Ali bin

˙

Ilyas Ali, who apparently functioned as the overseer of the

entire decorative programme. This latter person, known from other sources

342

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

as Nakkas¸ Ali (Ali the Designer), was a native of Bursa who had been carried off

to Transoxiana by Timur in 1402. There he evidently became familiar with the

Timurid style and in time, returning to Bursa, was instrumental in transmitting

aspects of Timurid design and visual culture back into his homeland. It is also

noteworthy that, according to the historian As¸ıkpas¸azade, the sultan’s vezir,

˙

Ivaz Pas¸a, who was both administrative overseer and architect of the Yes¸il

complex, brought craftsmen from Acem, that is from Iran, to work on it.

Timurid influence is also suggested by the range of colours employed in

the tilework of the Yes¸il complex and by the style of its decoration. Thus,

in addition to the turquoise and eggplant purple of Seljuk tilework, yellow,

green, white and a matt red are used. Likewise, new and richer styles of deco-

ration make their appearance, in particular spiralling leafy compositions with

convoluted cloud bands and the stylised lotus blossoms sometimes referred to

as hatayı or Cathayan. Deriving directly from the orientalising international

Timurid art of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, these elements are

played off against arabesques of split leaf palmettes and elongated pointed

foliage connected by slender, undulating stems in the rumi style, and geomet-

ric borders and bands of calligraphy. Indeed, the entire aesthetic of Mehmed’s

tomb is Timurid in the manner of Samarkand and Herat. And yet if foreign

influence is strongly felt in design, in range of colours, in glazing techniques

and in decorative motifs, it is significant that the tiles themselves are indis-

putably the work of local potters, for in their fabrics of red earthenware cov-

ered with white slip and lead glaze, they have no connection whatsoever with

the white frit tiles of Iran, but rather, are identical to contemporary ‘Miletus

wares’.

Thus,the ambitious use of glazedceramic asarchitectural decoration,which

had fallen into decline in fourteenth-century Anatolia, experienced a sudden

revival at the beginning of the fifteenth century. That this revival was the work

of an atelier of foreign craftsmen who identified themselves as the ‘Masters

of Tabriz’ is clear both from epigraphy and from the tile-making techniques

that they used. It is further apparent that the ‘Masters of Tabriz’ were not only

involved with Mehmed I’s great building programme, but continued in the

service of the Ottoman sultans for the next half-century. Although some of

their work is to be found in Bursa, in the mosque and medrese of the Muradiye

complex (828–30/1425–6), beginning around 1429 the key focus of their activity

appears to have shifted to Edirne. Here they were involved in the decoration

of the S¸ahmelek Camii (832/1429), and most significantly in Murad’s two key

monuments in that city, the Muradiye Camii (839/1436) and the

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli

Cami (847–51/1443–7). In the former, tiles are used to revet the enormous

343

howard crane

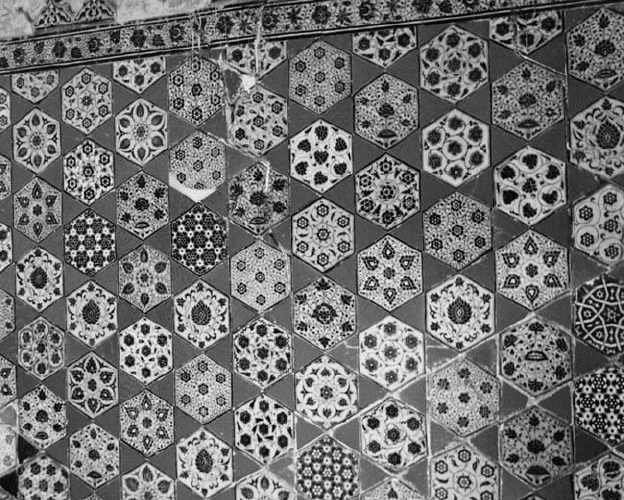

Figure 8.28 Muradiye, Edirne, detail of dado showing hexagonal blue-and-white tiles

(Photo Anthony Welch)

mihrab and the dado running around the three sides of the mihrab bay. The

former, executed largely in cuerda seca tiles, bears such a striking resemblance

to the mihrab of the Yes¸il Cami in Bursa that there can be little question but

that it too is the work of the same craftsmen.

At the same time, the Muradiye testifies to significant changes in the tech-

nical range of the ‘Masters of Tabriz’. The use of cut tile seems to have been

abandoned by them after 1425, while in the Muradiye a new type of cobalt

blue-and-white underglaze painted tile is introduced. This latter is encoun-

tered most strikingly in the dado of blue-and-white hexagonal and turquoise

green triangular tiles (Fig. 8.28) and is worthy of note for several reasons.

First, these are the earliest examples not only of underglaze painted tile but

also of blue-and-white ceramic to be produced by the Ottomans; and second,

they are the earliest Ottoman ceramics to be produced with white frit bodies.

Significantly, the frit fabric, while similar in appearance to that of later

˙

Iznik

wares, was produced using an alkaline frit technology typical of Iran rather

than the lead frit that is typical of later

˙

Iznik pottery.

344

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Among the 479 blue-and-whitehexagonal tiles of the dado,53 distinct painted

types can be identified. A number of these are geometric and radial compo-

sitions derived from the repertoire of Islamic design, but the majority are

inspired by Chinese blue-and-white wares of the Yuan and early Ming periods.

Chinoiserie forms encountered on these tiles include a type of distinctive lobed

and pointed leaf with pairs of spikes on either side familiar from fourteenth-

century Chinese porcelain, and lotus flowers, often outlined in the Chinese

manner on slender, sometimes curved or undulating stems, inspired by early

fifteenth-century Chinese blue-and-white wares.

Curiously, the tiles of the dado friezes are a later addition to the mosque.

This is shown by the fact that fragments of the painted (kalem is¸i) decoration

which originally covered the full elevation of the walls of the mihrab bay have

been found behind the dado tiles, making it clear that the latter were not part

of the Muradiye’s original decoration but were applied at some later date. Just

when that might have been is uncertain, but the blue-and-white hexagonal

tiles must have been produced by the same workshop as the mihrab and hence

be of approximately the same date as the mosque since moulded muqarnas

prisms in the frame and the border frieze of the cuerda seca mihrab are done in

underglaze blue-and-white.

The ‘Masters of Tabriz’ were also involved in the decoration of Murad II’s

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli Mosque, where they were commissioned to produce eighteen tiled

tympana for the windows of the courtyard. Only two of these have survived.

That they were the work of the ‘Masters of Tabriz’ is apparent from their

frames of running floral scrolls that are similar to those framing the dado

in the Muradiye. The fields of the two surviving lunettes are practically the

same, consisting of dramatic inscriptions in soaring thuluth script interlaced

with smaller inscriptions in an angular kufic, set against a background of

spiral stems and rumi leaves. Here the Tabrizi potters have abandoned the

cuerda seca technique and substituted for it a new polychrome underglaze

painted colour scheme in turquoise, cobalt blue and manganese purple which,

however, replicates to some degree the cuerda seca colour scheme.

The workshop of the ‘Masters of Tabriz’ continued to function into the

years following the conquest of Constantinople, as is clear from the presence

of two similar tympana in the courtyard of the Fatih Mosque in Istanbul, built

between 1463 and 1470. While reminiscent of the Edirne panels in design, they

arenotably differentinonerespect,namelythe inclusion of yellowin thepalette

of underglaze painted colours. That the workshop of the ‘Masters of Tabriz’

survived as late as the end of the 1470s seems apparent from an examination

of the so-called Tomb of Cem Sultan (884/1479) in Bursa, for although the

345

howard crane

workmanship of the blue and purple underglaze tiles in the dado borders and

tympana is of distinctly lesser quality than is that of the Muradiye tiles, their

designs – split palmettes in the borders, geometric motifs and palmettes on

the octagonal tiles of the tympana – clearly continue in a design tradition

having origins forty years earlier. Following the completion of the Tomb of

Sultan Cem, the production of underglaze painted frit tiles comes to an end

in western Turkey until revived in the second decade of the sixteenth century.

By that time, however, the workshop of the ‘Masters of Tabriz’ was no longer

in existence, for not only are the colour scheme and design of these tiles, now

associated with the potteries of early sixteenth-century

˙

Iznik, distinct from

those of the Tabriz potters, but the technology is one based on the use of the

lead frit preferred by Turkey rather than the alkaline frit used by the Iranian

craftsmen and their followers.

Woodcarving

Woodcarving

63

occupies an important place among the Turkish arts of Anato-

lia. Carefulworkmanship was lavished on architectural fittings and furnishings,

including minbers, lecterns (rahle), doors, window shutters, columns, capitals,

beams and consoles. Generally, these furnishings are fashioned of hard woods,

most especially of walnut, but also of apple, pear, cedar, ebony and rosewood.

While in general the woodwork of the beylik and early Ottoman periods fol-

lows closely the tradition of the preceding Seljuk period, a few new departures

do manifest themselves in both technique and style. These include not only

the incorporation into the wood craftsmen’s repertoire of pattern new motifs

such as the hatayı blossom from the international Timurid style, but also the

first tentative use of wood and bone inlay, a technique which appears in Cairo

at the end of the thirteenth and beginning of the fourteenth century and which

was to become especially important in the Ottoman art of the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries.

63 Woodwork of the beylik and early Ottoman periods is discussed in G

¨

on

¨

ul

¨

Oney,

‘Anadolu’da Selc¸uklu ve Beylikler Devri Ahs¸ap Teknikleri’, STY 3 (1969–70), 135–49;

Demiriz, Osmanlı Mimarisi’nde S

¨

usleme, I, Erken Devir, with general overview on pp. 24–

6, followed by discussion of various specific monuments; Hal

ˆ

uk Karama

˘

garalı, ‘C¸orum

Ulu C

ˆ

amiindeki Minber’, STY 1 (1964–5), 120–42;

¨

Om

¨

ur Bakirer, ‘

¨

Urg

¨

up’

¨

un Damsa

K

¨

oy

¨

u’ndeki Tas¸kın Pas¸a Camii’nin Ahs¸ap Mihrabı’, Belleten 35 (1971), 367–82 (with English

summary); M. Zeki Oral, ‘Anadolu’da San’at De

˘

geri Olan Ahs¸ap Minberler, Kitabeleri

ve Tarihc¸eleri’, Vakıflar Dergisi 5 (1962), 23–78. For the development of ivory, bone and

wood inlay in Egypt, see E. K

¨

uhnel, ‘Der Mamlukische Kassettenstil’, Kunst des Orients

1 (1950), 55–68.

346

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Of the techniques most commonly employed by the woodworker, either

alone or in combination with one another, the simplest involved the relief

carving of various motifs and profiles into a single plank. It was a technique

used especially for smaller architectural fittings such as shutters and the doors

of minbers, but required wood of high quality, without defects, and had as a

drawback the tendency of furnishings fashioned in this manner to warp or

split as they dried. To counteract this tendency, a second technique, that of

tongue-and-groove construction (k

¨

undekari), was used. Tongue-and-groove

construction seems to have developed in the twelfth century and appears in

Anatolia at about the same time as in late FatimidEgypt and Syria. Favoured for

the construction of mihrabs and doors with their broad, flat surfaces, k

¨

undekari

furnishings and fittings are made up of tongue-edged panels of polygonal or

stellate shape carved with arabesque relief, which are then fitted into grooved

frames. Because the grain of the panels runs in directions different from that

of the frame, warping is retarded and cracking or splitting counteracted. True

k

¨

undekari places high demands on the joiner’s skill, however, and as a result

a third technique, sometimes referred to as false k

¨

undekari, was developed,

whereby whole planks were carved in relief with the stellate and polygonal

patterns of true k

¨

undekari and were then mounted on the framework of a

minber or other piece of furniture with pins. In some rare instances, strips of

wood imitating in appearance the narrow frames of true k

¨

undekari panels were

nailed or glued into the channels between the relief carving on these planks as

well. Although the visual effect is that of true k

¨

undekari, this ‘false k

¨

undekari’

suffered from the same warping and splitting as furnishings cut from a single

plank.

A surprisingly large number of outstanding fourteenth- and early fifteenth-

century minbers and wooden architectural fittings bear inscriptions giving the

names and titles – neccar or der

¨

udger (carpenter) or as nakkas¸ (decorator) –

of the craftsmen who made them. In some cases, these inscriptions serve to

identify families through which the craft was transmitted. Muzaffereddin b.

Abd

¨

ulvahid b. S

¨

uleyman, who fashioned the minber of the Ulu Cami of Birgi

in 722/1322 at the command of Mehmed Bey, the emir of Aydın, for exam-

ple, was apparently the son of the carpenter (neccar) Abd

¨

ulvahid b. S

¨

uleyman,

who carved a lectern (rahle) of an unspecified date in the thirteenth century

now in the Islamic Museum in Berlin (No. j. 584). In other instances, several

works can be attributed by these inscriptions to a single craftsman. Thus, Hacı

Muhammed b. Abd

¨

ulaziz bin al-Dakı is known for two wooden minbers, that of

the Ulu Cami of Manisa, made by order of the Saruhanid ruler C¸ elebi

˙

Ishak b.

˙

Ilyas in 788/1376–7 f

ollowing the design (kataba khattahu wa rasama naqshahu)

347

howard crane

of a certain Yusuf b. Fakih, and that of the Ulu Cami of Bursa, executed at

the command of Sultan Bayezid b. Murad Han in 802/1399–1400.Thenakkas¸

Abdullah b. Mahmud worked in Kastamonu and Ankara during the second

half of the fourteenth century and is known for four works spanning a quarter-

century: a wooden cenotaph for the mausoleum of Ahi S¸erafeddin in Ankara

dated in Receb 751/September 1350; the doors of the mosque of

˙

Ibn Neccar in

Kastamonu dated 9 Zilhicce 758/23 November 1357; the doors of the mosque

of Mahmud Bey at Kasaba K

¨

oy

¨

u in the vicinity of Kastamonu, dated Ramazan

768/May 1367, and those of the Mahmud Bey Camii at Ilısu, dated 776/

1374–5.

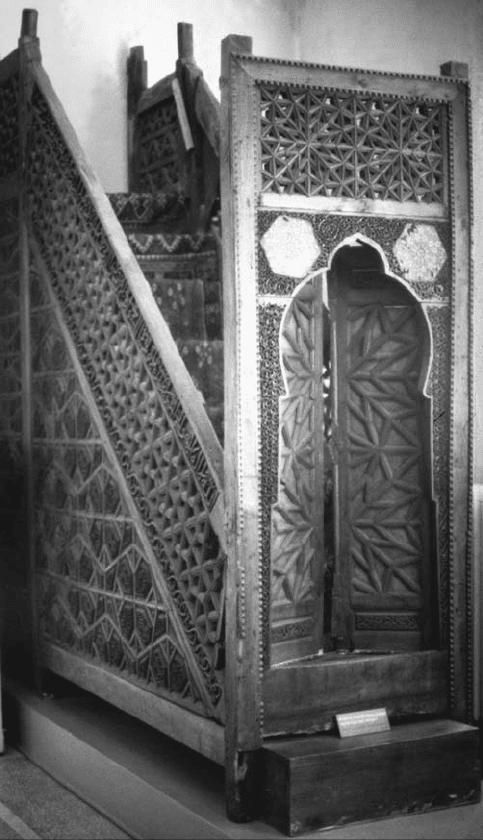

An outstanding example of a beylik minber done in the true k

¨

undekari tech-

nique is that of the Sungur Bey Camii in Ni

˘

gde (736/1335–6), now in the Dis¸

Cami in the same town, the work of Ebubekr b. Muallim. False k

¨

undekari

work can be seen in the unique wooden mihrab of the mosque of Tas¸kın Pas¸a

in Damsa K

¨

oy

¨

u dating to the middle of the fourteenth century, today in the

Ethnographic Museum in Ankara, and the minber of the Ulu Cami of C¸ orum,

dated 10 Safer 706/22 August 1306, signed by two craftsmen who identify them-

selves by their nisbas as having links with Ankara, Davud bin Abdullah and

Muhammed bin Ebubekr. Earlier work by the latter is found in the minbers

of two late thirteenth-century mosques in Ankara, the Arslanhane Camii and

the no longer extant Kızıl Bey Mescidi (the latter minber today in pieces in

the Ethnographic Museum). From a technical point of view, the minber of the

Tas¸kın Pas¸a Camii in Damsa K

¨

oy

¨

u

(mid-fourteenth century) (Fig. 8.29)and

the inner door of the T

¨

urbe of Hacı Bayram Veli from Ankara (early fifteenth

century), both today in the Ethnographic Museum in Ankara, are of special

interest for the fact that they combine bone and wood inlay. In the former

the inlay is found in a pair of rosettes in hexagonal frames in the spandrels of

its gateway, while in the latter it is used in the stars and polygons filling the

geometric strapwork on its face.

The earliest example of Ottoman woodcarving is a shutter of the Orhan

Camii in Gebze, dating to the mid-fourteenth century. Consisting of three

walnut panels in a frame of the same wood, it is a rather unambitious example

of true k

¨

undekari, carved in a single plane of relief. This arrangement into three

panels, so typical of beylik and Ottoman shutters and doors,is encountered also

on the leaves of the main door of the Bayezid Pas¸a Camii in Amasya (817/1414).

While the upper panels of the two leaves are filled with calligraphy, the large

rectangular panels in the middle of each leaf is inscribed in its upper part and

filled with an infinite pattern based on a twelve-pointed star below. Finally,

the bottom panels are decorated with infinite patterns of palmettes. Like

348

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Figure 8.29 Minber bone inlay, Tas¸kın Pas¸a Camii, Damsa K

¨

oy

¨

u,

¨

Urg

¨

up

(today in the Etnografya M

¨

uzesi, Ankara) (Photo Walter B. Denny)

349