Fleet K. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 1, Byzantium to Turkey, 1071-1453

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

howard crane

dating to Bayezid’s original foundation, while the one on the north-east was

probably added by Mehmed I between 815/1413 and 821/1421.

While the domes of the Ulu Cami of Bursa are all of equal dimension, the

mihrab axis is nonetheless highlighted by the raised elevation of the domes

placed along it. This tendency to emphasise the mihrab and its axis is char-

acteristic of beylik and early Ottoman-period congregational mosques, and

accounts for the placement of the transept on the mihrab axis of the

˙

Isa Bey

Camii of Ayasoluk, for the increased breadth and height of the central nave

of ‘basilical’ mosques like the Sungur Bey Camii of Ni

˘

gde and the Ulu Cami

of Birgi, and for the large dome constructed over the mihrab bay of Latifiye

Camii in Mardin. Of course, none of these devices are the innovations of the

fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century builders. All have antecedents reaching

back to the earliest centuries of Islamic architecture and are encountered in

buildings such as the Great Mosque of Qairawan in Tunisia and the Azhar

and Hakim mosques in Cairo, not to mention the Seljuk-period mosques of

thirteenth-century Anatolia. Rather more original was a tendency in some bey-

lik and early Ottoman congregational mosques of the hypostyle type to merge

several bays before the mihrab under a single larger dome, a tendency not only

giving expression to the importance of the mihrab, but reflective as well of an

ongoing interest on the part of Anatolian Turkish architects in experimenting

with domical vaulting and pushing its limits as covering for ever larger interior

spaces (as in the closed court medreses of Celaleddin Karatay and Fahreddin Ali

in Konya). In western Anatolia towards the end of the fourteenth century, this

tendency to experiment with the construction of large domes, now over the

mihrab bays of multi-bay hypostyle congregational mosques, is encountered

in the Ulu Cami (778/1376) of Manisa (Fig. 8.8).

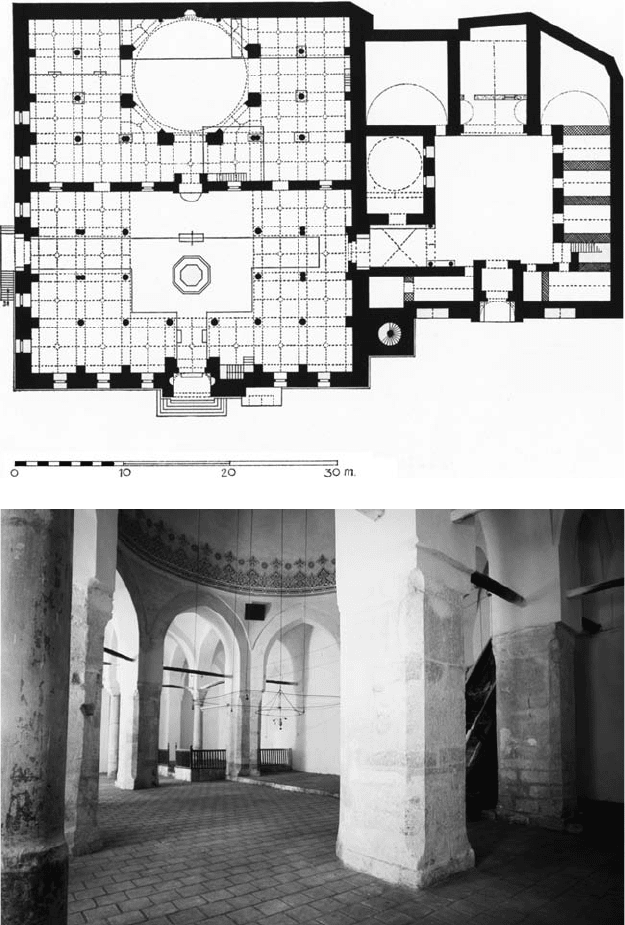

Built by

˙

Ishak Bey, the ruler of the principality of Saruhan, it has been

described as having the most important and most interesting plan of any of

the fourteenth-century mosques in Anatolia. It was built as part of a complex

including, in addition to the mosque, a medrese and the tomb of the founder,

both contiguous to it on the west. In plan, the mosque is formed of two

approximately equal spaces, a prayer hall on the south and a portico-enclosed

fountain court on the north, both measuring approximately 16 by 30 metres.

Not only are the dimensions similar; the plans of the two units mirror one

another as well. Thus, the prayer hall, nine bays wide and four bays deep, is

covered by a series of small domical vaults, except for the space, equivalent

to nine bays, before the mihrab niche. This latter is surmounted by a single

large dome of 10.8 metres on pendentives, carried by an octagon of arches

supported by six great piers and the kıble wall. Although the placement of

290

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

(a)

(b)

Figure 8.8 (a, b)

˙

Ilyas Bey Camii, Manisa, plan (after Riefstahl, Southwestern Anatolia,

fig. 3) and view of prayer hall interior (Photo Walter B. Denny)

291

howard crane

a large dome on an octagon before the mihrab niche to create a prayer hall

with unified interior space has, possibly, some tenuous connection with similar

arrangements in south-east Anatolian mosque architecture of the twelfth and

early thirteenth century, the use of this formula in the Ulu Cami of Manisa

represents a new development for western Anatolia, one which was to be

of considerable significance for the later evolution of Ottoman architecture.

Important as well in the context of Ottoman architectural development is the

courtyard of

˙

Ishak Bey’s mosque. Like the prayer hall, it measures seven bays

in width and four in depth, but with the area on the south, again equivalent

to nine bays, left open and forming a fountain court immediately before the

prayer hall fac¸ade. This open, arcaded fountain courtis a feature almost entirely

absent from Anatolian Seljuk mosque architecture, and along with the large

dome of the prayer hall, is a feature which anticipates developments more fully

expressed in the Ottoman architecture of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

It is in mosques such as the G

¨

uzelce Hasan Bey Camii (809/1406–7)of

Hayrabolu near Tekirda

˘

g and, more significantly, in the

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli Cami of

Edirne (841–51/1437–47) that these tendencies first manifested in the Manisa

mosque are taken up by the Ottomans. The

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli Mosque, in particular

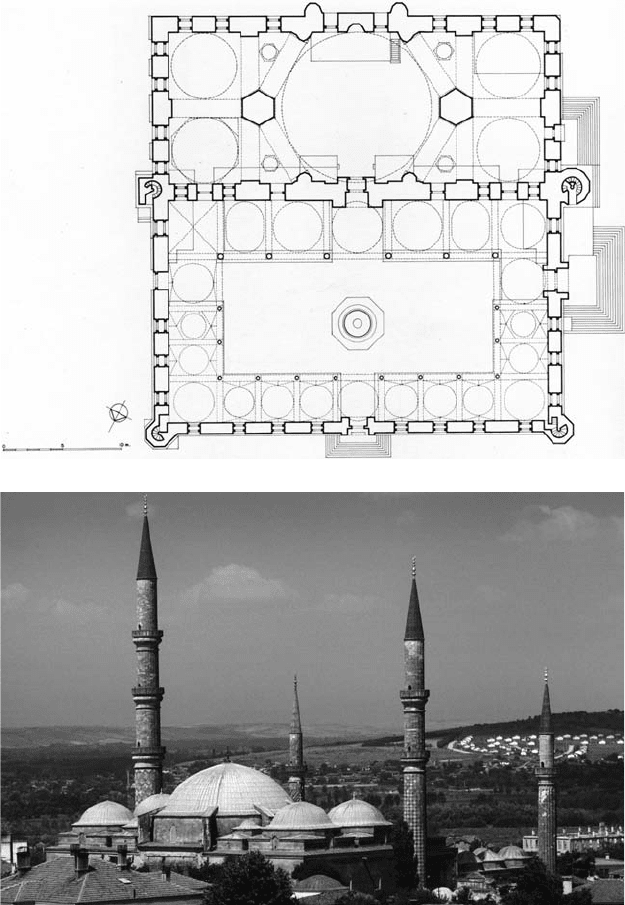

(Fig. 8.9), represents a bold leap in both planning and structure. Built by Murad

II in the years immediately before the conquest of Constantinople, the mosque

is almost square in layout, measuring 66.5 by 64.5 metres, with an oblong prayer

hall approximately two-thirds as deep as the fountain court that precedes it.

The courtyard, which can be entered through the main portal on the north

and a lateral gateway on the west, is surrounded by a portico covered by

twenty-two round and elliptical domes of various sizes, with five bays along

the south side of the courtyard and seven along its north. It is the oblong prayer

hall, however, which is the most distinguishing feature of Murad’s mosque.

Like the Ulu Cami of Manisa, it can be seen as a multi-domed congregational

mosque of eight units, the four central units of which have been merged

and covered by a large central dome of 24 metres. The effect produced by

its lower flanking domes and high central dome is one that foreshadows the

pyramidal massing of volumes characteristic of the great imperial mosques

of Istanbul of the sixteenth century. In contrast to the Ulu Cami of Manisa,

the central dome of the Edirne mosque is carried on a hexagon, supported

on north and south by the walls of the prayer hall and on east and west by

a pair of enormous hexagonal piers. On the exterior, the dodecagonal drum

of the central dome is reinforced by eight flying buttresses, apparently the

first use of this device in Ottoman architecture. As seen from the interior, the

central dome completely dominates the senses, although the perception of

292

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

(a)

(b)

Figure 8.9 (a, b)

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli Cami, Edirne, plan (after Kuran, Mosque,p.177, courtesy

University of Chicago Press) and view of covering showing arrangement of prayer hall

domes (Photo Walter B. Denny)

293

howard crane

spatial unity that it is intended to produce is decreased by the low hang of the

hexagon’s arches. Four minarets of unequal height and disparate design are set

at the corners of the courtyard, that at the south-west, soaring to a height of

67.65 metres,being, after the minaretsof the nearby SelimiyeCamii,the highest

in Ottoman architecture. Its three balconies (s¸erefe) give Murad’s mosque its

name.

The

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli Cami is, thus, a kind of climax to Turkish architectural

developments of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, deriving as it

does, on the one hand, from the Anatolian hypostyle congregational mosque

of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and, on the other, from the con-

tinuing experimentation by Turkish builders with the construction of ever

more expansive domical vaults. In both plan and structure, the mosque must

be seen as the point of departure for the development of the great mosques

dominated by vast, centralising domes that characterise Ottoman architecture

of the classical period of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

17

Finally, in addition to simple single-domed mosques and a variety of con-

gregational mosques, art historical literature frequently distinguishes a third

Turkish mosque type of the fourteenth and early fifteenth century, the so-

called Bursa or reverse-T mosque. Recent research suggests that this latter

type was, in fact, a multi-purpose building serving a variety of functions, edu-

cational, social and religious, and with this in mind the term zaviye-mosque

has been proposed to describe it. Arguments in favour of the multi-functional

explanation have been most systematically put forth by Semavi Eyice, who

notes that these buildings are typically characterised by a T-plan with a dome-

covered mihrab hall on the kıble side of the building, a dome-covered fountain

court behind it, symmetrically arranged chambers flanking the fountain court

on right and left, and a portico along the north fac¸ade. Minarets, where they

exist, can generally be shown to be later additions.

More than sixty structures of this sort dating to the fourteenth and fif-

teenth centuries are still extant, almost all of them on territories which had

been brought within the frontiers of the Ottoman principality. Early examples

include the Nil

¨

ufer Hatun

˙

Imareti (790/1388) and Yakub C¸ elebi Zaviyesi (late

fourteenth century) in

˙

Iznik, and the Firuz Bey Camii (797/1394–5) in Milas.

It is in Bursa and Edirne, however, that the finest buildings of this sort are to

be found, among them the H

¨

udavendigar

˙

Imareti (767–87/1366–85)ofMurad

17 For the Ulu Cami of Bursa, Ayverdi, OM

˙

ID,pp.401–18; Gabriel, Une capitale turque, i,

pp. 31–9;Kuran,Mosque,pp.151–3. For the Ulu Cami of Manisa, see Riefstahl, Southwest

Anatolia,pp.7–15; for the

¨

Uc¸S¸erefeli of Edirne, Kuran, Mosque,pp.177–81; Aslanapa,

Turkish Art and Architecture,pp.203–5; Ayverdi, C¸SMD,pp.422–62.

294

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

IinC¸ ekirge, Yıldırım Bayezid’s Bayezid

˙

Imareti (begun c.793/1390) in Bursa’s

eastern suburbs, and Murad II’s Muradiye Camii (830/1426) to the west of the

Hisar and Muradiye Zaviyesi (839/1436) on the northern outskirts of Edirne,

each the core of a larger complex including tombs, medreses, hamams and

imarets.

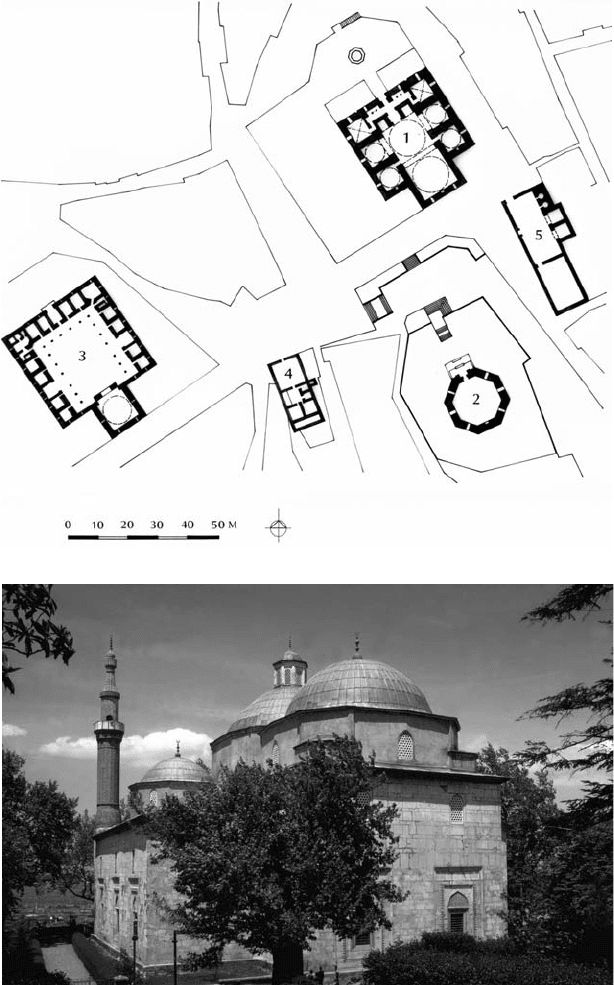

Unquestionably the most spectacular of the zaviye-mosques of Bursa is the

Ye s¸il Cami (822/1419–20) (Fig. 8.10), built by C¸ elebi Mehmed, with work on its

decoration continuing until 1424.Partofak

¨

ulliye including a medrese, imaret

and tomb, its architect was Hacı

˙

Ivaz b. Ahi Bayezid, who also built the C¸ elebi

Sultan Mehmed Camii (824/1421) at Dimetoka in eastern Thrace. The mosque

was originally preceded by a five-bay portico that collapsed in the earthquake

of 1855. In its present form, therefore, the fac¸ade is divided into two storeys,

reflecting the two-storey elevation of the entry block behind it. While the

windows on the first storey are enclosed in muqarnas frames and richly carved

blind arches, those of the second storey are designed as balconies and contain

low, openwork stone balustrades. The tall portal, extending to the roofline, is

recessed into the fac¸ade. Carved with low-relief vegetal interlace decoration,

it represents a clear break with the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century design

and is the first in an imperial Ottoman style which will be continued with little

change until the nineteenth century.

In the interior the mosque has four eyvans – three large and one small –

opening on the domed central fountain court. That on the south contains a

mihrab and functioned as a prayer hall. The two side eyvans, slightly smaller in

size, are each flanked by a pair of rooms, while the smaller north eyvan was the

entrance passage. The lavishly decorated entrance block includes a second-

storey balcony overlooking the fountain court which must have functioned

as an imperial tribune (h

¨

unkar mahfili). While the entrance eyvan is covered

by a barrel vault, the side eyvans, kıble eyvan and central courtyard are all

covered by domes on belts of Turkish triangles and squinches. An octagonal

pool stands at the centre of the fountain court under the dome’s nineteenth-

century lantern that replaced the open oculus of the fifteenth century. Also of

nineteenth-century date are the two minarets that stand at the corners of the

entry fac¸ade.

While there is little in the overall design of the Yes¸il Cami to distinguish it

from other contemporary zaviye-mosques in Bursa and Edirne, its decoration

imparts to it a quality of richness and exuberance that supports its claim to

be

the most beautiful of early Ottoman architectural monuments. Indeed, it

seems no effort or expense was spared in its construction and embellishment.

Built of carefully drafted stone, its fac¸ade, portal and window frames are all of

295

(a)

(b)

Figure 8.10 (a, b) Yes¸il complex, Bursa, site plan and view of south-west exterior of

mosque (Photo Walter B. Denny)

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

marble. But the most sumptuous part of the mosque is its interior, originally

enriched with painted (kalem is¸i) foliate arabesques, some traces of which still

survive to the present day, and by extravagant revetments of cuerda seca tiles

recalling in both technique and aspiration the expansive tile fac¸ades of Timurid

Samarkand and Herat.

18

While popular opinion and some architectural historians continue to hold

that these T-plan buildings were mosques, as the current name of C¸ elebi

Mehmed’s foundation, Yes¸il Cami, would seem to affirm, scholars have long

puzzled over the function of the side rooms which flank the central court,

describing them as, among other things, halls of state and medreses. It was

the Turkish architect Sedat C¸ etintas¸ who first advanced the notion that they

functioned as zaviyes, that is, as hospices for itinerant dervishes and travellers,

an idea which was further supported by the research of Semavi Eyice, who saw

their most immediate precursors in such buildings as the thirteenth-century

hanekah of the Sahib Ata Fahreddin Ali (678/1279–80) adjoining his Larende

Camii in Konya. That the side rooms do seem to have functioned as hospice

rooms (tabhane) is suggested by the presence in them of built-in cupboards and

fireplaces, which could be used for storage and for the comfort of guests. Even

more telling is the fact that in their foundation inscriptions, their vakfiyes and

other contemporary documents, many of these buildings are referred to not

as mosques but as imaretsorzaviyes. Thus, despite their present designations,

these buildings seem to have been multi-purpose structures, serving the needs

not only of worship but also of charity and learning. Their foundation appears

to have been associated in at least some cases with ahi fraternities, those semi-

religious orders of late Seljuk and early Ottoman times recruited mainly from

among the ranks of craftsmen devoted to the ideals of f

¨

ut

¨

uvva. While intended

to provide shelter for travellers (Ibn Battuta’s account of his travels in early

fourteenth-century Anatolia includes descriptions not only of hospices of this

sort but of the ahis who maintained them), they at the same time provided

moral and material support for the process of Turkicisation and Islamicisation

in newly settled areas during the period of Ottoman expansion. Subsequently,

as the ahi orders lost their original character in the sixteenth century, these

zaviye-mosques lost some of these functions and were transformed into the

simple mosques that they are today.

19

18 See the section on ceramics, pp. 336–46, below.

19 For an important general discussion of the so-called ‘Bursa’ type mosques and their

function, see Eyice, ‘

˙

Ilk Osmanlı Devrinin Din

ˆ

ı-

˙

Ic¸tima

ˆ

ı bir M

¨

uessesesi’, pp. 3–80. For the

Ye s¸il Cami, see Ayverdi, C¸SMD,pp.46–94; Gabriel, Une capitale turque,pp.79–94.

297

howard crane

Medreses

Medreses of the beylik and early Ottoman periods continue the two types of

Seljuk medreses of the thirteenth century. The more common of these, the open

court type, is found not only in Anatolia but in the Ottoman Balkans as well.

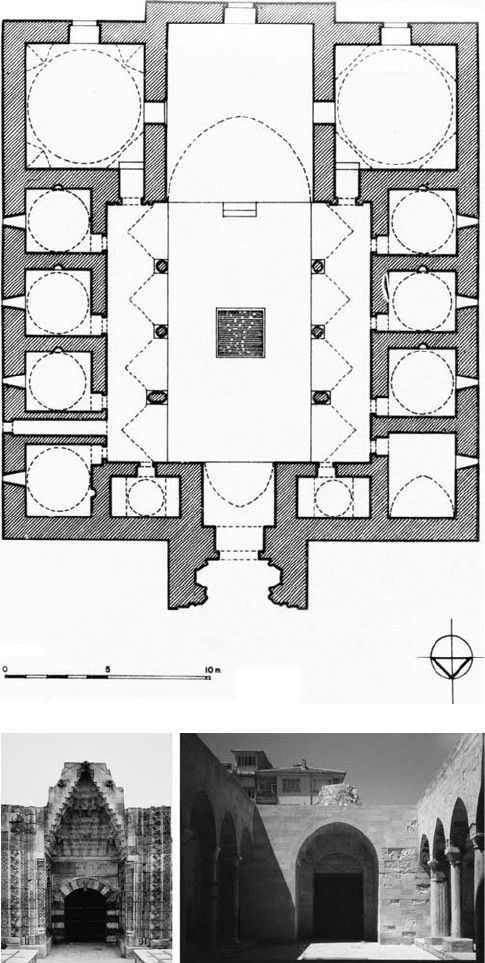

A fine example is the Hatuniye Medrese (783/1381–2) (Fig. 8.11) in Karaman

founded by Nefise Sultan, the wife of the Karamanid ruler Alaeddin Bey and

daughter of the Ottoman sultan Murad I. Symmetrical in plan, the building

has a heavily decorated and rather archaic gateway copied from that of the

thirteenth-century G

¨

ok Medresesi in Sivas, which projects strongly from the

north fac¸ade. Beyond the gateway, a small entry eyvan flanked by a pair of

small domed rooms gives access to the medrese’s central courtyard. The sides

of the courtyard were bordered by arcaded porticos of reused columns, behind

which were domed student rooms. At the back of the courtyard a raised eyvan

presumably served as the summer classroom (dershane). In the traditional

Seljuk manner, it is flanked on either side by a pair of square, domed rooms

entered through doors enclosed by frames richly carved with palmette and

lotus motifs. Although her cenotaph (sanduka) is no longer extant, the room

to the left of the eyvan originally contained the tomb of the founder, while

that to the right was perhaps a winter classroom. Meinecke has established

that both the eyvan and the tomb chamber had dados of dark turquoise-green

glazed hexagonal tiles and it may well be that the cenotaph was revetted with

faience as well. An inscription on the gateway identifies the architect (mimar)

as Hoca Ahmad b. Nu‘man. Although the medrese is today heavily restored, it

is clear that it was originally the most richly decorated building of Karaman.

Similarly planned beylik open court medreses include the Karamanid Tol

Medrese (740/1339–40) in Ermenak and the Hatuniye Medrese (835/1431–2)in

Kayseri, the Hamidid Dyndar Bey Medresesi (701/1301–2)ofE

˘

gridir and the

Ilkhanid Bimarhane (708/1308) of Amasya. The finely wrought Ak Medrese

(812/1409–10)ofNi

˘

gde is remarkable for its two-storey construction and

for its balcony of Gothic-appearing bipartite arcades, rather like that of the

H

¨

udavendigar

˙

Imareti at Bursa, across the second storey of the main fac¸ade.

The large and traditional Zincirli Medrese (mid-fifteenth century) of Aksaray

is notable for its four-eyvan plan.

Closed court medreses, although rather rare in the beylik period, derive like

their open court counterparts from Seljuk models. The earliest beylik exam-

ples, the Ilkhanid Yakutiye (710/1310–11)

and Ahmediye (714/1314–15) medreses,

were built in Erzurum. Both have rectangular centralcourts covered with groin

and barrel vaults recalling the hospital of Turan Melik (626/1228–9) in Divri

˘

gi.

298

(a)

(b) (c)

Figure 8.11 (a, b, c) Hatuniye Medrese, Karaman, plan (Bo

˘

gazic¸i

University, Aptullah Kuran Archive), view of portal (Photo Bernard O’Kane)

and view of courtyard (Photo Katharine Branning)