Fleet K. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 1, Byzantium to Turkey, 1071-1453

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

(a)

(b)

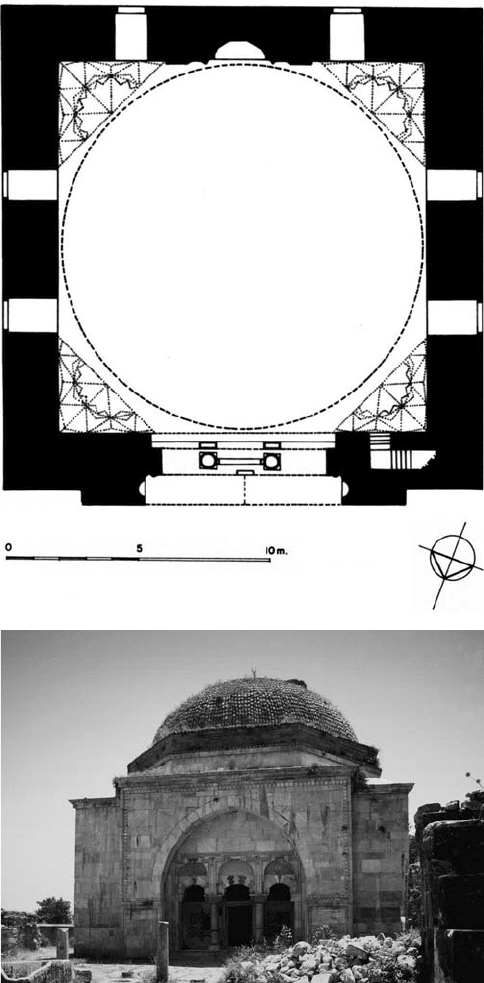

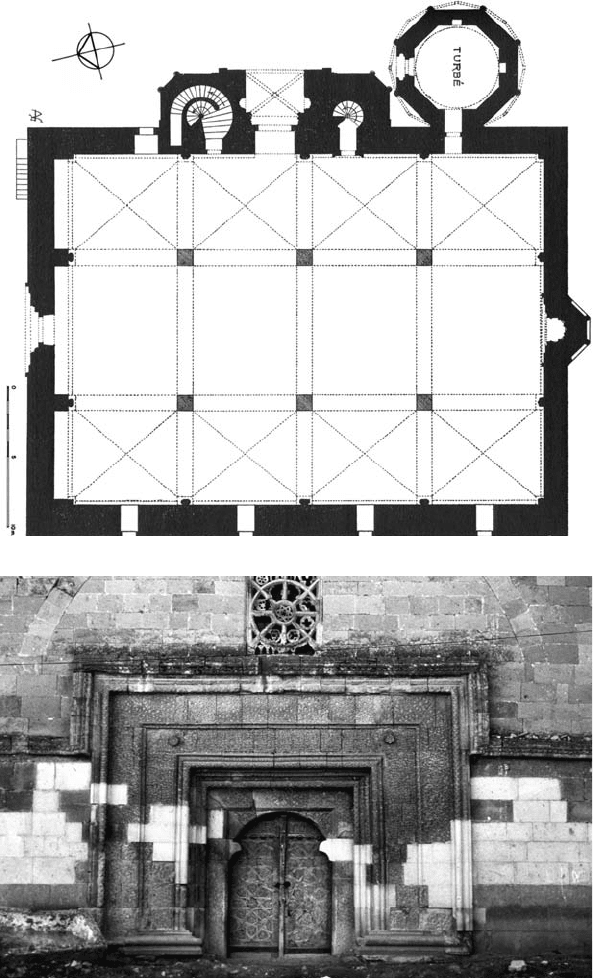

Figure 8.2 (a, b)

˙

Ilyas Bey Camii, Balat (Miletus), plan and view of north fac¸ade

(Photo Walter B. Denny)

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

Antique monuments of Miletus. In old photographs a brick minaret can be

seen adjoining its north-west corner. The square prayer hall is covered by

a 14-metre dome on squinches filled with Turkish triangles and scalloped

fluting. Illumination is provided by two rows of windows, the lower ones

covered by iron grates while the upper windows are screened with marble

grilles of geometric openwork. On their exteriors these windows are framed

by varied torus and muqarnas mouldings and are spanned by relief-carved

lintels enriched with geometric, epigraphic and vegetal compositions, some

inlaid in blue and red marble intarsia work. The eyvan-like porch on the north

fac¸ade, virtually unique in Anatolia, encloses three hipped arches of bichrome

(ablak) voussoirs in the Mamluk style, carried on reused Antique columns

with muqarnas capitals. Geometric openwork screens close off the openings

to the right and left of the central gateway bay. The interior of the mosque

is dominated by a magnificent marble mihrab framed by borders of muqarnas

and geometric strapwork with vegetal compositions in the spandrels and six

rows of muqarnas in its half dome. The stone carving of the

˙

Ilyas Bey Camii,

extraordinary for its meticulous and elegant workmanship, makes the Balat

mosque one of the outstanding monuments of the period of the emirates.

Typologically, however, the mosque belongs to the simple, single-dome group,

although its dome is one of the largest of the period.

A common variant on the single-dome mosque has a portico (son cemaat

yeri) of two, three or five domed or vaulted bays across the entry fac¸ade.

This arrangement is encountered in fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century

mosques throughout Anatolia and the Balkans, including the mosques of Hacı

¨

Ozbek (734/1333–4)in

˙

Iznik,

˙

Ibn Neccar (754/1353) in Kastamonu, the Kurs¸unlu

Camii (779/1377–8)inK

¨

utahya, the Ak Mescid (800/1397–8) in Afyon, the Kara-

hasan Camii (early fifteenth century) in Tire and the Eski Cami (811/1408–9)at

Za

˘

gra in Bulgaria. A further variant is characterised by an extension in one or

more directions of the mosque’s interior space beyond the limits of the square,

dome-covered bay. Such is the case, for example, with the Orhan Gazi Camii at

Bilecik (early fourteenth century), covered by a dome measuring c.9.50 metres

supported on four enormous corner piers linked by pointed arches so as to

form an interior with a cruciform plan. A more common variant, found in

Murad II’s Dar

¨

ulhadis Camii (838/1434–5) in Edirne, has a vestibule between

the portico on the mosque’s entry fac¸ade and the domed prayer hall. The most

outstanding example of this arrangement is the Yes¸il Cami in

˙

Iznik (Fig. 8.3),

constr

ucted by the architect (banı) Hacı bin Musa between 780/1378 and

794/1392 for C¸ andarli Halil Hayreddin Pas¸a (d. 1387). The mosque’s portico

of three bays is covered by a flat-topped cross-vault, with a tall octagonal drum

281

(a)

(b)

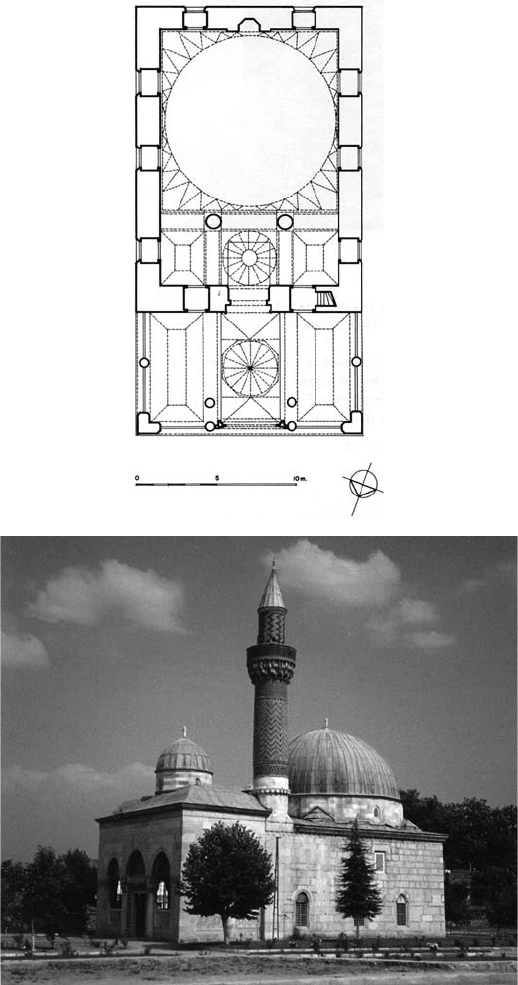

Figure 8.3 (a, b) Yes¸il Cami,

˙

Iznik, plan (Bo

˘

gazic¸i University, Aptullah

Kuran Archive) and view from north-west (Photo Katharine Branning)

Art and architecture, 1300–1453

topped by a fluted dome rising from the centre vault. The square prayer hall,

a typical single-domed square mosque, has a belt of Turkish triangles in the

zone of transition. Between the prayer hall and the portico stands a vestibule

screened from the rest of the mosque’s interior by a pair of massive columns

linked by pointed arches. Consisting of three bays, the vestibule, in its vaulting,

mirrors the portico, with the centre vault supporting a tall fluted dome with

a blind lantern. The exterior of the mosque, like that of

˙

Ilyas Bey at Balat, is

revetted with a veneer of marble, which is applied to the lower part of the

interior walls as well. As with the Balat mosque, a brick minaret adjoins the

mosque on the right and is decorated in the Seljuk manner with glazed tiles,

from the colours of which the mosque, not surprisingly, derives its name.

14

Many, although by no means all, single-domed mosques functioned as

mahalle or small neighbourhood mosques. Congregational mosques (cami)

were generally larger than most single-dome mosques and were characterised

by a wide variety of plans, including both hypostyle and basilical arrangements.

The most conservative of these congregational mosques are to be found in

central Anatolia, in the principality of Karaman, and are distinguished by one

or more arcades or colonnades running parallel to the kıble wall, as in the Ulu

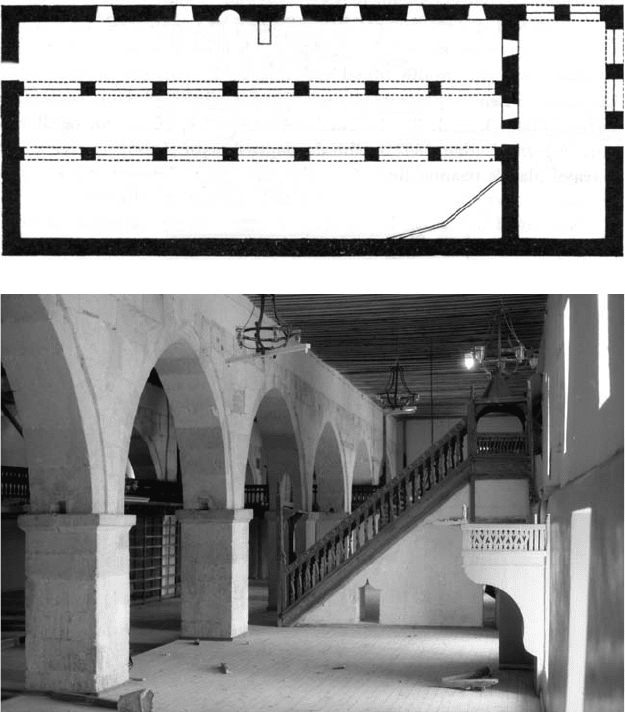

Cami (1302–3) of Ermenak (Fig. 8.4). A plainly constructed building of roughly

drafted stone, it has a rectangular prayer hall divided into three aisles by squat,

heavy masonry arcades. A small entry vestibule stands to the west of the

prayer hall and the entire structure was covered by a flat timber and earthen

roof. Recalling in its plan such Seljuk period mosques as the east wing of the

Alaeddin Camii (probably before 1155) of Konya, the Ulu Cami of Ermenak

finds Karamanid parallels in the Hacıbeyler (759/1357–8), Arapzade (1374–1420)

and Dikbasan mosques (840/1436) of Karaman.

While the Ulu Cami of Ermenak was no doubt the reflection of an indige-

nous, Anatolian vernacular tradition, other related mosques with aisles paral-

leling the kıble wall, but with large, domed bays or transepts on the axis of the

mihrab, have Syrian connections. The earliest examples of this type are to be

found in the Artukid lands of south-east Anatolia. Examples include the Ulu

Cami of Diyarbakır (seventh century but rebuilt in 1091–2 and restored later),

the Ulu Cami of Mayyafarikin (Silvan, finished in 1157) and the Ulu Cami of

Dunaysir (601/1204). That mosques of this sort continued to be built in south-

east Anatolia into the fourteenth century is attested by the Latifiye Camii

14 For the

˙

Ilyas Bey Camii in Balat (Miletus), see Aynur Durukian, Balat

˙

Ilyas Bey Camii

(Ankara, 1988); K. Wulzinger, P. Wittek and F. Sarre (eds.), Das Islamische Milet (Berlin,

1935). The Yes¸il Cami of

˙

Iznik is treated by Otto-Dorn, ‘Das Islamische

˙

Iznik’, pp. 20–33;

Ayverdi, OM

˙

ID,pp.309–19;Kuran,Mosque,pp.61–3.

283

howard crane

(a)

(b)

Figure 8.4 (a, b) Ulu Cami, Ermenak, plan (based on Diez et al., Karaman Devri Sanatı,

p. 6) and view of prayer hall interior along kıble wall (Photo Bildarchiv/image archive

Das Bild des Orients, Berlin, photographer J. Gierlichs)

of Mardin (772/1371), built by a certain ‘Abd al-Laif b. ‘Abdallah, an official in

the service of the Artukid rulers Melik Mahmud el-Salih and Melik Davud II el-

Muzaffer. It was in the principality of Aydın in western Anatolia, however, that

the most interesting and historically significant example of this sort of mosque

was built in the fourteenth century. The

˙

Isa Bey Camii (776/1375) (Fig. 8.5)in

Ayasoluk, built by the emir of Aydın

˙

Isa b. Muhammad, is a large rectangular

284

(a)

(b)

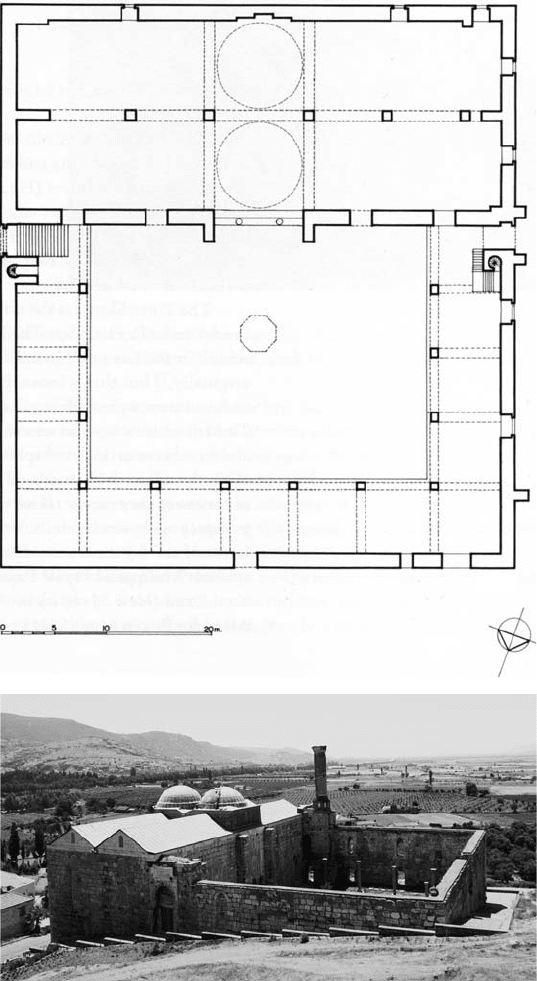

Figure 8.5 (a, b)

˙

Isa Bey Camii, Ayasoluk, plan (after Kuran, Mosque,p.62,

courtesy University of Chicago Press) and view from south (Photo Walter B. Denny)

howard crane

structure measuring some 52 by 56 metres, enclosed by high walls of limestone

and marble, much of it spoils from the nearby ruins of Ephesus. While the

north, east and south walls are of roughly drafted masonry, that on the west is

fashioned of carefully cut stone, emphasising its importance as the mosque’s

main fac¸ade. Within, the

˙

Isa Bey Camii is divided into a long, narrow prayer

hall on the south preceded on the north by a rectangular courtyard, formerly

enclosed by colonnaded porches on three sides. Three gateways give access

to the courtyard, one on the north, and another pair functioning as well as

the plinths of a pair of minarets, at the point where, on east and west, the

porches join the prayer hall. In its interior the prayer hall is divided by a

colonnade into a pair of aisles paralleling the kıble, which in turn are cut by a

transept of two domed bays on triangular pendentives on the axis of the mihrab.

The antecedent for this plan is immediately apparent as being found in the

Umayyad caliph al-Walid’s early eighth-century Great Mosque of Damascus, a

connection which is explained by the name of the architect, ‘Ali b. al-Dimashqi,

given in the construction text over the west portal. This Syrian link is further

emphasised by the portal’s tall, narrow dimensions, by the angular knotting

in bichrome marble reminiscent of Ayyubid Aleppo in its spandrels and by the

bichrome (ablak) joggled joints of the relieving arches over the lower windows

of the west fac¸ade.

15

A second type of beylik-period congregational mosque has columns or piers

arranged in rows perpendicular to the kıble wall to form a central nave and

side aisles. Like the Ulu Cami of Ermenak, the origins of this ‘basilical’ type

are to be sought in Seljuk mosque architecture of the thirteenth century, in

buildings such as the Ulu Cami (626/1229)ofDivri

˘

gi, the Alaeddin Camii

(620/1223)ofNi

˘

gde, and the Es¸refo

˘

glu Camii (699/1299–1300)ofBeys¸ehir. A

particularly fine fourteenth-century example is Sungur Bey Camii (736/1335–6)

of Ni

˘

gde (Fig. 8.6) with its unusual north and east portals (the latter flanked

by a pair of minarets) and its manifestly Gothic features, including bipartite

and rose windows and a ribbed pointed groin vault in the east porch, inspired

perhaps by Cilician Armenian architects. Although much modified following

a fire in the eighteenth century, there can be no question but that the interior

was originally divided by arcades into a central nave and side aisles covered

by groin and star vaults (although Gabriel speculates that the bays of the

nave were covered with domes). In the principalities of western Anatolia,

15 For the Ulu Cami of Ermenak, see Diez et al., Karaman Devri Sanatı,pp.5–7; Kızıltan,

Anadolu Beyliklerinde Cami,p.20; the mosques of Karaman are discussed in ibid., pp. 26–9;

also Diez et al., Karaman Devri Sanatı,pp.35–43. For the

˙

Isa Bey Mosque in Ayasoluk, see

Otto-Dorn, ‘Die Isa Bey Moschee in Ephesus’.

286

(a)

(b)

Figure 8.6 (a, b) Sungur Bey Camii, Ni

˘

gde, plan (after Gabriel, Monuments turcs d’Anatolie,

i,p.125) and view of north portal (Photo Walter B. Denny)

howard crane

‘basilical’ plans are found in the Ulu Cami of Birgi (712/1312–13), the Ulu Cami

of Tire (early fifteenth century) and the Mahmud Bey Camii (768/1366–7)of

Kasaba K

¨

oy

¨

u near Kastamonu. Examples from the Ottoman lands include the

Yıldırım Camii of Bergama (801/1398–9), the H

¨

udavendigar Camii of Plovdiv

(c.1389) and, following

˙

I. H. Ayverdi and Robert Anhegger’s reconstructions,

the S¸ehadet Camii in the Hisar of Bursa (767/1365–6).

16

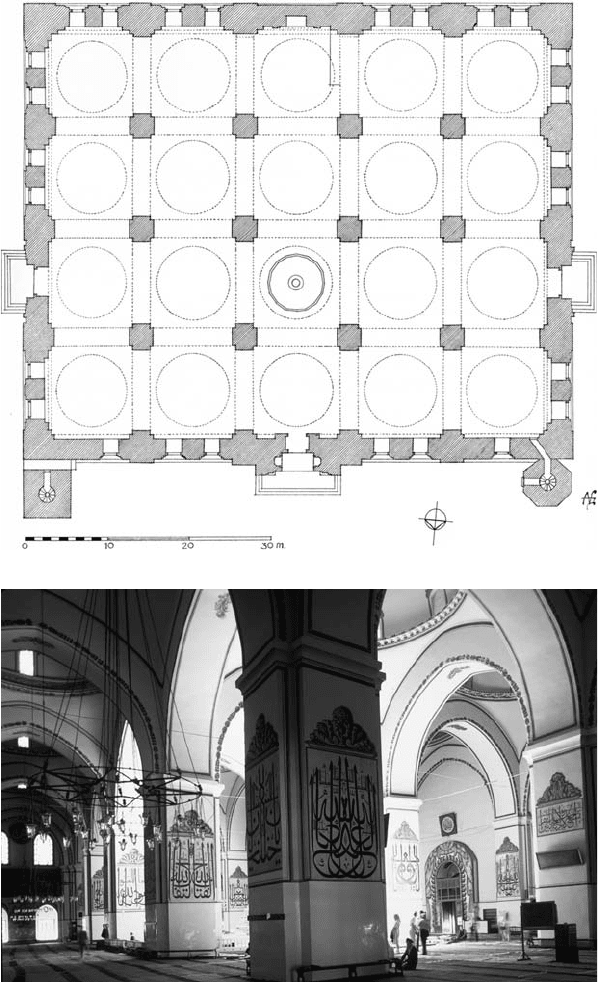

Still another type of congregational mosque, one associated most closely

with the Ottomans, is characterised by a hypostyle arrangement of piers

or columns which divide the interior into a multiplicity of equal bays, each

covered with a separate dome. An early example is the Hamidid Yivli Minare

Camii (774/1373) of Antalya, divided by twelve reused columns into six equal

bays covered by domes on Turkish triangles. Built on the foundations of an

earlier Byzantine church, the symmetry of the mosque is disrupted by the awk-

ward trapezoidal extension of the prayer hall on the west. Other examples of

this domed hypostyle type are to be found in what was the Ottoman principal-

ity, the two most outstanding being the Ulu Cami of Bursa (c.802/1399–1400)

builtbyBayezidI to commemoratehis victoryin the battle of Ni

˘

gbolu (Nikopo-

lis), and the Eski Cami of Edirne (805–16/1403–14), begun by S

¨

uleyman C¸ elebi

and completed by his brother Musa. The former (Fig. 8.7), a large, rectangular

building measuring 68 by 56 metres, is built of finely drafted limestone with

exterior fac¸ades enlivened and unified by blind arcades that mirror each row

of domes and frame two storeys of windows. The main entrance in the north

fac¸ade is a projecting portal in the Seljuk manner, although its carving is less

exuberant than that of most of its thirteenth-century antecedents. In the inte-

rior the mosque is divided into twenty equal bays by twelve enormous piers,

with each bay in turn being covered by a hemispheric dome on pendentives.

The dome at the intersection of the mosque’s longitudinal and transverse axes

as established by its north portal and mihrab niche, and its two side portals, has

an open oculus beneath which there is a sixteen-sided pool with a fountain.

Although on the interior the domes appear equal in height, it is apparent on the

exterior that as one moves from the sides towards the centre the elevation of

each row of domes is increased. The mosque, though devoid of a portico, has

two minarets, placed at the corners of the north fac¸ade, that on the north-west

16 For the Sungur Bey Camii, Ni

˘

gde, see Gabriel, MTA, i,pp.123–35; for the Ulu Cami of

Birgi, Riefstahl, Southwest Anatolia,pp.26–30; the Ulu Cami of Tire, Aslano

˘

glu, Tire,

pp. 24–6. For the Yıldırım Camii in Bergama, the H

¨

udavendigar Camii in Plovdiv and

the S¸ehadet Camii in Bursa, see Oktay Aslanapa, Turkish Art and Architecture (New York,

1971), p. 196; Ayverdi, OM

˙

ID,pp.267–75, 295–303, 373–8; Robert Anhegger, ‘Beitrage

zur Fr

¨

uhosmanischen Baugeschichte’, in Zeki Vel

ˆ

ıd

ˆ

ı Togan’a Arma

˘

gan (Istanbul, 1950–5),

pp. 301–30.

288

(a)

(b)

Figure 8.7 (a, b) Ulu Cami, Bursa, plan (Bo

¨

yazic¸i University, Aptullah Kuran Archive)

and interior of prayer hall (Photo Walter B. Denny)