Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Beach renourishment

During the early 1970s there was a proposal to develop

a huge tidal-power facility at the upper Bay of Fundy, to

harvest commercial energy from the immense, twice-daily

flows of water. The tidal barrage would have extended across

the mouth of Minas Basin, a relatively discrete embayment

with a gigantic tidal flow. Partly because of controversy

associated with the enormous environmental damages that

likely would have been caused by this ambitious develop-

ment, along with the extraordinary construction costs and

untried technology, this tidal-power facility was never built.

A much smaller, demonstration project of 20 MW was

commissioned in 1984 at Annapolis Royal in the upper Bay,

and even this facility has caused significant local damages.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Thurston, H. Tidal Life: A Natural History of the Bay of Fundy. London:

Camden House Publishing, 1990.

The 2000 Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: McLelland and Stewart.

Beach renourishment

Beach renourishment, also called beach recovery or replen-

ishment, is the act of rebuilding eroded beaches with offshore

sand and gravel that is dredged from the sea floor. Renour-

ishment projects are sometimes implemented to widen a

beach for more recreational capacity, or to save structures

built on an eroding sandy shoreline. The process is one that

requires ongoing maintenance; the shoreline created by a

renourished beach will eventually erode again. According to

the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA), the estimated cost of long-term restoration of a

beach is between $3.3 and $17.5 million per mile.

The process itself involves

dredging

sand from an

offshore site and pumping it onto the beach. The sand

“borrow” or dredging site must also be carefully selected to

minimize any negative environmental impact. Dredging can

stir up

silt

and bottom

sediment

and cut off oxygen and

light to marine

flora

and

fauna

.

Under the Energy and Water Development Appropri-

ations Act of 2002, 65% of beach renourishment costs are

paid for with federal funds, and the remaining 35% with

state and local monies. Beach renourishment programs are

often part of a state’s coastal zone management program. In

some cases, state and local government work with the U.S.

Army Corp of Engineers to evaluate and implement an

erosion

control program such as beach renourishment.

Environmentalists argue that renourishment is for the

benefit of commercial and private development, not for the

117

benefit of the beach. Erosion is a natural process governed

by weather and sea changes, and critics charge that tampering

with it can permanently alter the

ecosystem

of the area in

addition to threatening endangered sea turtle and seabird

nesting habitats.

In some cases, it is the coastal development that brings

about the need for costly renourishment projects. Coastal

development can hasten the erosion of beaches, displacing

dunes

and disrupting beach grasses and other natural barri-

ers. Other human constructions, such as sea walls and other

armoring, can also alter the shoreline.

Results of a U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers

Study

completed in 2001—the Biological Monitoring Program for

Beach Nourishment Operations in Northern New Jersey

(Manasquan Inlet to Asbury Park Section)—found that al-

though dredging in the borrow area had a negative impact

on local marine life, most

species

had fully recovered within

24–30 months. Further studies are needed to determine the

full long-range impact of beach renourishment programs on

biodiversity

and local coastal habitats.

[Paula Anne Ford-Martin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dean, Cornelia. Against the Tide: The Battle for America’s BeachesNew York:

Columbia University Press, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Cen-

ter. The New York District’s Biological Monitoring Program for the Atlantic

Coast of New Jersey, Asbury Park to Manasquan Section Beach Erosion Control

Project Final Report, 2001.

U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Admin-

istration, National Ocean Service, Office of Ocean & Coastal Resource

Management. “State, Territory, and Commonwealth Beach Nourishment

Programs: A National Overview.” OCRM Program Policy SeriesTechnical

Document No. 00-01 (March 2000).

O

THER

National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, Coastal Services Center.

Beach Renourishment in the Southeast http://www.csc.noaa.gov/opis/html/

beach.htm. Accessed June 5, 2002.

Bear

see

Grizzly bear

Mollie Beattie (1947 – 1996)

American forester and conservationist

Mollie Hanna Beattie was trained as a forester, worked as

a land manager and administrator, and ended her brief career

as the first woman to serve as director of the U.S.

Fish

and Wildlife Service

. Beattie’s bachelor’s degree was in

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bellwether species

philosophy, followed by a master’s degree in forestry from

the University of Vermont in 1979. Later (in 1991), she

used a Bullard Fellowship at Harvard University to add a

master’s degree in public administration.

Early in her career, Mollie Beattie served in several

conservation

administrative posts and land management

positions at the state level. She was commissioner of the

Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and

Recreation

(1985–1989), and deputy secretary of the state’s Agency of

Natural Resources

(1989–1990). She also worked for pri-

vate foundations and institutes: as program director and

lands manager (1983–1985), for the Windham Foundation,

a private, nonprofit organization concerned with critical is-

sues facing Vermont, and later (1990–1993), as executive

director of the Richard A. Snelling Center for Government

in Vermont, a public policy institute.

Before becoming director of the Fish and

Wildlife

Service, Beattie was perhaps most widely known (especially

in New England) for the book she co-authored on managing

woodlots in private ownership, an influential guide reissued

in a second edition in 1993. As a reviewer noted about the

first edition, for the decade it was in print “thousands of

landowners and professional foresters [recommended the

book] to others.” Especially noteworthy is the book’s empha-

sis on the responsibility of private landowners for effective

stewardship of the land. This background was reflected in

her thinking as Fish and Wildlife director by making the

private lands program—conservation in partnership with pri-

vate land-owners—central to the agency’s conservation ef-

forts.

As director of the Fish and Wildlife Service, Beattie

quickly became nationally known as a strong voice for conser-

vation and as an advocate for thinking about land and

wild-

life management

in

ecosystem

terms. One of her first

actions as director was to announce that “the Service [will]

shift to an ecosystem approach to managing our fish and

wildlife resources.” She emphasized that people use natural

ecosystems for many purposes, and “if we do not take an

ecosystem approach to conserving

biodiversity

, none of

[those uses] will be long lived.”

Her philosophy as a forester, conservationist, adminis-

trator, and land manager was summarized in her repeated

insistence that people must start making better connec-

tions—between wildlife and

habitat

health and human

health; between their own actions and “the destiny of the

ecosystems on which both humans and wildlife depend;”

and between the well-being of the

environment

and the

well-being of the economy.” She stressed “even if not a single

job were created, wildlife must be conserved” and that the

diversity of natural systems must remain integral and whole

because “we humans are linked to those systems and it is in

our immediate self interest to care” about them. She reiter-

118

ated that in any frame greater than the short-term, the

economy and the environment are “identical considerations.”

Though Beattie’s life was relatively short, and her ten-

ure at the Fish and Wildlife Service cut short by illness,

her ideas were well received in conservation circles and her

influence continues after her death, helping to create what

she called “preemptive conservation,” anticipating crises be-

fore they appear and using that foresight to minimize con-

flict, to maintain biodiversity and sustainable economies,

and to prevent extinctions.

[Gerald L. Young]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Beattie, M., C. Thompson, and L. Levine. Working With Your Woodland:

A Land-Owner’s Guide. Rev. ed. Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New

England, 1993.

Beattie, M. “Biodiversity Policy and Ecosystem Management.” In Biodiver-

sity and the Law, edited by W. J. Snape III. Washington, D.C.: Island

Press, 1996.

P

ERIODICALS

Beattie, M. “A Broader View.” Endangered Species Update 12, no. 4/5 (April/

May, 1995): 4–5.

———. “An Ecosystem Approach to Fish and Wildlife Conservation.”

Ecological Applications 6, no. 3 (August 1996): 696–699.

———. “The Missing Connection: Remarks to Natural Resources Council

of America.” Land and Water Law Review 29, no. 2 (1994): 407–415.

Cohn, J. P. “Wildlife Warrior.” Government Executive 26, no. 2 (February

1994): 41–43.

Bees

see

Africanized bees

Bellwether species

The term bellwether came from the practice of putting a

bell on the leader of a flock of sheep. The term is now used

to describe an indicator of a complex of ecological changes.

Bellwether

species

are also called indicator species and are

seen as early warning signs of environmental damage and

ecosystem

change.

Ecologists have identified many bellwether species in

various ecosystems, including the Attwater

prairie

chicken(-

Tympanuchus cupido attwateri), the Northern diamondback

terrapin(Malaclemys terrapin terrapin), the Northern and

Southern giant petrels (Macronectes giganteus and M. halli),

and the polar bear(Ursus maritimus). There are many more.

Problems with these species are extreme indicators of trou-

bles within their ecosystems.

The Attwater prairie chicken is almost extinct. It once

numbered in the millions in Louisiana and along the Texas

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Hugh Hammond Bennett

coast. The Northern and Southern giant petrels, large

scav-

enger

birds of the Antarctic Peninsula, are also heading

towards

extinction

as

commercial fishing

fleets head fur-

ther and further south. In Massachusetts’ Outer Cape, con-

servationists are trying to save the Northern diamondback

terrapin. Troubles for the Arctic polar bear are indicating

ecosystem change in the Arctic, as humans interact more

and more with that ecosystem.

[Douglas Dupler]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Helvarg, David. “Elegant Scavengers: Giant Petrels are a Bellwether Species

for the Threatened Antarctic Peninsula.” E Magazine, November/Decem-

ber, 1999. <http://www.emagazine.com>.

Walsh, J. E. “The Arctic as a Bellwether.” Nature, no. 352 (1999): 19–20.

Below Regulatory Concern

Large populations all over the globe continue to be exposed

to low-level radiation. Sources include natural

background

radiation

, widespread medical uses of

ionizing radiation

,

releases and leakages from

nuclear power

and weapons

manufacturing plants and waste storage sites. An added po-

tential hazard to public health in the United States stems

from government plans to deregulate

low-level radioactive

waste

generated in industry, research, and hospitals and

allow it to be mixed with general household trash and indus-

trial waste in unprotected dump sites.

The

Nuclear Regulatory Commission

(NRC) plans

to deregulate some of this

radioactive waste

and treat it

as if it were not radioactive. The makers of radioactive waste

have asked the NRC to treat certain low levels of

radiation

exposure

with no regulations. The NRC plan, called Below

Regulatory Concern (BRC), will categorize some of this

waste as acceptable for regular dumping or

recycling

. It will

deregulate radioactive consumer products, manufacturing

processes and anything else that their computer models proj-

ect would, on a statistical average, cause radiation exposures

within the acceptable range. The policy sets no limits on

the cumulative exposure to radiation from multiple sources

or exposures or multiple human use.

In July 1991 the NRC responded to public pressure

and declared a moratorium on the implementation of BRC

policy. This was a temporary move, leaving the policy intact.

The U. S. Department of Energy (DoE) has already dumped

radioactive trash on unlicensed incinerators. Although DoE

is not regulated by the NRC, this action reflects an adoption

of the BRC concept. If the BRC plan is eventually approved,

radioactive waste will end up in local landfills, sewage sys-

tems, incinerators, recycling centers, consumer products and

119

building materials,

hazardous waste

facilities and farm-

land (through

sludge

spreading).

Some scientists maintain that there are acceptable low

levels of radiation exposure (in addition to natural back-

ground radiation) that do not pose a threat to public health.

Other medical studies conclude that there is no safe level

of radiation exposure. Critics claim BRC policy is nothing

more than linguistic

detoxification

and will, if imple-

mented, inevitably lead to increased radiation exposure levels

to the public, and increased risk of

cancer

,

birth defects

,

reduced immunity, and other health problems. Implementa-

tion of BRC may also mean that efficient cleanup of contam-

inated

nuclear weapons

plants (Oak Ridge, Savannah

River, Fernald), nuclear reactors, and other radioactive facili-

ties might not be completed.

Its critics contend that BRC is basically a financial,

not a public health, decision. The nuclear industry has pro-

jected that it will save hundreds of millions of dollars if BRC

is implemented.

[Liane Clorfene Casten]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Below Regulatory Concern, But Radioactive and Carcinogenic. Washington,

DC: U. S. Public Interest Research Group, 1990.

Low-Level Radioactive Waste Regulation—Science, Politics and Fear. Chelsea,

MI: Lewis, 1988.

Below Regulatory Concern: A Guide to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s

Policy on the Exemption of Very Low-Level Radioactive Materials, Wastes

and Practices. Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1990?.

Hugh Hammond Bennett (1881 –

1960)

American soil conservationist

Dr. Bennett, a noted conservationist, is often called the

father of

soil conservation

in the United States. He was

born on April 13, 1881, in Anson County, North Carolina,

and died July 7, 1960. He is buried in Arlington National

Cemetery.

Dr. Bennett graduated from the University of North

Carolina in 1903. After completing his university education,

he became a

soil

surveyor in the Bureau of Soils of the

U.S. Department of Agriculture

. He recognized early the

degradation to the land from soil

erosion

and in 1929

published a bulletin entitled “Soil Erosion, A National Men-

ace.” Soon after that, the nation began to heed the admoni-

tions of this young scientist.

In 1933, the U.S. Department of Interior set up a Soil

Erosion Service to conduct a nation-wide demonstration

program of soil erosion, with Bennett as its head. In 1935,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Benzene

the

Soil Conservation Service

was established as a perma-

nent agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and

Bennett became its head, a position he retained until his

retirement in April 1951. He was the author of several

books and many technical articles on soil

conservation

.He

received high awards from many organizations and several

foreign countries.

Dr. Bennett traveled widely as a crusader for soil con-

servation, and was a forceful speaker. Many colorful stories

about his speeches exist. Perhaps the most widely quoted

concerns the dust storm that hit Washington D.C. in the

spring of 1935 at a critical moment in Congressional hearings

concerning legislation that, if passed, would establish the

Soil Conservation Service. A huge dust cloud that had started

in the Great Plains was steadily moving toward Washington.

As the storm hit the district, Dr. Bennett, who had been

testifying before members of the Senate public lands com-

mittee, called the committee members to a window and

pointed to the sky, darkened from the dust. It made such

an impression that legislation was promptly approved, estab-

lishing the Soil Conservation Service.

Dr. Bennett was an outstanding scientist and crusader,

but he was also an able administrator. He visualized that if

the Soil Conservation Service was to be effective, it must

have grass roots support. He laid the foundation for the

establishment of the local soil conservation districts with

locally elected officials to guide the program and Soil Con-

servation Service employees to provide the technical support.

Currently there are over 3,000 districts (usually by county).

The National Association of Conservation Districts is a

powerful voice in matters of conservation. Because of Dr.

Bennett’s leadership in the United States, soil erosion was

increasingly recognized worldwide as a serious threat to the

long-term welfare of humans. Many other countries then

followed the United States’ lead in establishing organized

soil conservation programs.

[William E. Larson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bennett, H. H. Soil Conservation. Manchester: Ayer, 1970.

Benzene

A hydrocarbon with chemical formula C

6

H

6

, benzene con-

tains six

carbon

atoms in a ring structure. A clear volatile

liquid with a strong odor, it is one of the most extensively

used

hydrocarbons

. Because it is an excellent solvent and

a necessary component of many industrial

chemicals

, in-

cluding

gasoline

, benzene is classified by United States

federal agencies as a known human

carcinogen

based on

120

studies that show an increased incidence of nonlymphocytic

leukemia

from occupational exposure and increased inci-

dence of neoplasia in rats and mice exposed by inhalation

and gavage. Because of these cancer-causing properties, ben-

zene has been listed as a hazardous air pollutant under Sec-

tion 112 of the

Clean Air Act

.

Benzo(a)pyrene

Benzo(a)pyrene [B(a)P] is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

(PAH) having five aromatic rings in a fused, honeycomb-

like structure. Its formula and molecular weight are C

20

H

12

and 252.30, respectively. It is a naturally occurring and man-

made organic compound formed along with other PAH in

incomplete

combustion

reactions, including the burning

of

fossil fuels

, motor vehicle exhaust, wood products, and

cigarettes. It is classified as a known human

carcinogen

by the EPA, and is considered to be one of the primary

carcinogens in

tobacco smoke

. Synthesized in 1933, it was

the first carcinogen isolated from

coal

tar and often serves

as a surrogate compound for

modeling

PAHs.

Wendell Erdman Berry (1934 – )

American writer, poet, and conservationist

A Kentucky farmer, poet, novelist, essayist and conservation-

ist, Berry has been a persistent critic of large-scale industrial

agriculture—which he believes to be a contradiction in

terms—and a champion of environmental stewardship and

sustainable agriculture

. Wendell Erdman Berry was born

on August 5, 1934, in Henry County, Kentucky, where his

family had farmed for four generations. Although he learned

the farmer’s skills, he did not wish to make his living as a

farmer but as a writer and teacher. He earned his B.A. in

English at the University of Kentucky in 1956 and an M.A.

in 1957. He was awarded a

Wallace Stegner

writing fellow

at Stanford University (1958–1959), where he remained to

teach in the English Department (1959–1960). He spent

the following year in Italy on a Guggenheim fellowship. In

1962 Berry joined the English faculty at New York Uni-

versity.

Dissatisfied with urban life and feeling disconnected

from his roots, in 1965 Berry resigned his professorship of

English at New York University to return to his native

Kentucky to farm, to write, and to teach at the University

of Kentucky. His recurring themes—love of the land, of

place or region, and the responsibility to care for them—

appear in his poems and novels and in his essays. Many

modern farming practices, as he argues in The Unsettling of

America (1977) and The Gift of Good Land (1981) and else-

where, deplete the

soil

, despoil the

environment

, and deny

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Best available control technology

the value of careful husbandry. In relying on industrial scales,

techniques and technologies, they fail to appreciate that

agriculture is agri-culture—that is, a coherent way of life

that is concerned with the care and cultivation of the land—

rather than agri-business concerned solely with maximizing

yields, efficiency, and short-term profits to the long-term

detriment of the land, of family farms, and of local communi-

ties. A truly sustainable agriculture, as Berry defines it,

“would deplete neither soil, nor people, nor communities.”

Berry believes that too few people now live on and

farm the land, leaving it to the less-than-tender mercies of

corporate “managers” who know more about accounting than

about agricultural stewardship. The so-called miracle of

modern agriculture has been purchased by selling our birth-

right, the God-given gift of good land that Americans have

heedlessly traded for the ease, convenience and affluence of

urban and suburban living. As a consequence we have be-

come disconnected from our cultural roots and have lost a

sense of place

and purpose and pleasure in work well done.

We have also lost a sense of connection with the land and

the lore of those who work on and care for it. Instead of

food from our own fields, water from rainfall and

wells

,

and stories from family and friends, most Americans now

get food from the grocery store, water from the faucet, and

endless entertainment from television. A wasteful throwaway

society produces not only material but cultural junk—throw-

away farms, throwaway marriages and children, disposable

communities, and a wanton disregard for the natural envi-

ronment. The transition to a culture of consumption and

convenience, Berry believes, does not represent progress so

much as it marks a deep and lasting loss.

Although Berry does not believe it possible (or desir-

able) that all Americans become farmers, he holds that we

need think about what we do daily as consumers and citizens

and how our choices and activities affect the land. He sug-

gests that the act of planting and tending a garden is a

“complete act” in that it enables one to connect consumption

with production, and both to a sense of reverence for the

fertility and abundance of a world well cared for.

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Berry, Wendell. A Continuous Harmony: Essays Cultural and Agricultural.

New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

———. A Place on Earth. rev. ed. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1983.

———. Another Turn of the Crank. Washington, DC: Counterpoint

Press, 1995.

———. Collected Poems, 1957–1982. San Francisco: North Point Press,

1985.

———. The Gift of Good Land. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1981.

———. Home Economics. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1981.

121

———. Sex, Economy, Freedom and Community. New York: Pantheon

Books, 1993.

———. The Unsettling of America. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1977.

———. What Are People For? San Francisco: North Point Press, 1990.

Merchant, Paul, ed. Wendell Berry. American Authors Series. Lewiston,

Idaho: Confluence Press, 1991.

Best available control technology

Best available control technology (BACT) is a standard used

in

air pollution control

in the prevention of significant

deterioration (PSD) of

air quality

in the United States.

Under the

Clean Air Act

, a major stationary new source of

air pollution

, such as an industrial plant, is required to have

a permit that sets

emission

limitations for the facility. As

part of the permit, limitations are based on levels achievable

by the use of BACT for each pollutant.

To prevent risk to human health and public welfare,

each region in the country is placed in one of three PSD

areas in compliance with National Ambient Air Quality

Standards (NAAQS). Class I areas include national parks

and

wilderness

areas, where very little deterioration of air

quality is allowed. Class II areas allow moderate increases in

ambient concentrations. Those classified as Class III permit

industrial development and larger increments of deteriora-

tion. Except for national parks, most of the land in the

United States is set at Class II.

Under the Clean Air Act, the BACT standards are

applicable to all plants built after the effective date, as well

as preexisting ones whose modifications might increase

emissions of any pollutant. To establish a major new source

in any PSD area, an applicant must demonstrate, through

monitoring and diffusion models, that emissions will not

violate NAAQS or the Clean Air Act. The applicant must

also agree to use BACT for all pollutants, whether or not

that is necessary to avoid exceeding the levels allowed and

despite its cost. The

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) requires that a source use the BACT standards, unless

it can demonstrate that its use is infeasible based on “substan-

tial and unique local factors.” Otherwise BACT, which can

include design, equipment, and operational standards, is re-

quired for each pollutant emitted above minimal defined

levels.

In areas that exceed NAAQS for one or more pollut-

ants, permits are issued only if total allowable emissions of

each pollutant are reduced even though a new source is

added. The new source must comply with the

lowest

achievable emission rate

(LAER), the most stringent lim-

itations possible for a particular plant.

Under the Clean Air Act, if a new stationary source

is incapable of BACT standards, it is subject to the

New

Source Performance Standard

(NSPS) for a pollutant, as

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Best management practices

determined by the EPA. NSPSs take into consideration the

cost and energy requirements of emission reduction pro-

cesses, as well as other health and environmental impacts.

This contrasts with BACT standards, which are determined

without regard to cost. Strict BACT requirements resulted

in a more than 20% reduction in particulates and

sulfur

dioxide

below NSPS levels.

[Judith Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Findley, R. W., and D. A. Farber. Environmental Law. St. Paul, MN:

West Publishing Company, 1992.

Plater, Z. J. B., R. H. Abrams, and W. Goldfarb. Environmental Law and

Policy: Nature, Law, and Society. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Com-

pany, 1992.

Best management practices

Best management practices (BMPs) are methods that have

been determined to be the most effective and practical means

of preventing or reducing non-point source

pollution

to

help achieve

water quality

goals. BMPS include both mea-

sures to prevent pollution and measures to mitigate pollution.

BMPS for agriculture focus on reducing non-point

sources of pollution from croplands and farm animals. Ag-

ricultural

runoff

may contain nutrients,

sediment

, animal

wastes, salts, and pesticides. With

conservation tillage

,

crop residue, which is plant residue from past harvests, is

left on the

soil

surface to reduce runoff and soil

erosion

,

conserve soil moisture, and keep nutrients and pesticides on

the field. Contour strip farming, where sloping land is

farmed across the slopes to impede runoff and soil movement

downhill, reduces erosion and sediment production. Manag-

ing and accounting for all

nutrient

inputs to a field ensures

that there are sufficient nutrients available for crop needs

while preventing excessive nutrient

loading

, which may re-

sult in

leaching

of the excess nutrients to the ground water.

Various BMPs are available for keeping insects, weeds, dis-

ease, and other pests below economically harmful levels.

Conservation

buffers, including grassed waterways,

wet-

lands

, and riparian areas act as an additional barrier of

protection by capturing potential pollutants before they move

to surface waters. Cows can be kept away from streams

by streambank fencing and installation of alternative water

sources. Designated stream crossings can provide a con-

trolled crossing or watering access, thus limiting streambank

erosion and streambed trampling.

Coastal shorelines can also be protected with BMPs.

Shoreline stabilization techniques include headland breaker

systems to control shoreline erosion while providing a com-

122

munity beach. Preservation of shorelines can be accom-

plished through revegetation, where living plant materials

are a primary structural component in controlling erosion

caused by land instability.

Stormwater management in urban developed areas also

utilize BMPs to remove pollutants from runoff. BMPS in-

clude retention ponds, alum treatment systems, constructed

wetlands, sand

filters

, baffle boxes, inlet devices, vegetated

swales,

buffer

strips, and infiltration/exfiltration trenches.

A storm drain stenciling programs is an educational BMP

tool to remind persons of the illegality of dumping litter, oil,

pesticides, and other toxic substances down

urban runoff

drainage

systems.

Logging

activities can have adverse impacts on stream

water temperatures, stream flows, and water quality. BMPS

have been developed that address location of logging roads,

skid trails, log landings and stream crossings, riparian man-

agement buffer zones, management of litter and fuel and

lubricant spills, and reforestation activities.

Successful control of erosion and

sedimentation

from

construction and mining activities involves a system of BMPs

that targets each stage of the erosion process. The first stage

involves minimizing the potential sources of sediment by

limiting the extent and duration of land disturbance to the

minimum needed, and protecting surfaces once they are

exposed. The second stage of the BMP system involves

controlling the amount of runoff and its ability to carry

sediment by diverting incoming flows and impeding inter-

nally generated flows. The third stage involves retaining

sediment that is picked up on the project site through the use

of sediment-capturing devices.

Acid

drainage from mining

activities requires even more complex BMPs to prevent acids

and associated toxic pollutants from harming surface waters.

Other pollutant sources for which BMPS have been

developed include

atmospheric deposition

, boats and ma-

rinas,

habitat

degradation, roads, septic systems, under-

ground storage tanks, and

wastewater

treatment.

[Judith L. Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Urban Water Infrastructure Management Committee. A Guide for Best

Management Practice (BMP) Selection in Urban Developed Areas. Reston,

VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, 2001.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.NPDES Best Management Practices

Manual.Rockville, MD: Government Institutes, ABS Group, Inc., 1995.

O

THER

Logging and Forestry Best Management Practices.Division of Forestry, Indiana

Department of Natural Resources. May 30, 2001. [June 15, 2002]. <http://

www.state.in.us/dnr/forestry/bmp/logindex.htm>

Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

Control.North Carolina State University Water Quality Group. June 15,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Beyond Pesticides

2002. [June 17, 2002]. <http://h2osparc.wq.ncsu.edu/info/bmps_for_

agnps.html>

Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Non-Agricultural Nonpoint Source

Pollution Control: Nonpoint Source Pollution Control Measures—Source Cate-

gories.North Carolina State University Water Quality Group. June 15, 2002.

[June 17, 2002]. <http://h2osparc.wq.ncsu.edu/info/bmps.html>

Best practical technology

Best practical technology (BPT) refers to any of the catego-

ries of technology-based

effluent

limitations pursuant to

Section 301(b) and Sections 304(b) of the

Clean Water Act

as amended. These categories are the best practicable control

technology currently available (BPT); the

best available

control technology

(BAT) economically feasible (BAT);

and the best

conventional pollutant

control technology

(BCT).

Section 301(b) of the Clean Water Act specifies that

“in order to carry out the objective of this Act there shall

be achieved—(1)(A) not later than July 1, 1977, effluent

limitations for point sources, other than publicly owned

treatment works (i) which shall require the application of

the best practicable control technology currently available as

defined by the Administrator pursuant to Section 304(b) of

this Act, or (ii) in the case of

discharge

into a publicly

owned treatment works which meets the requirements of

subparagraph (B) of this paragraph, which shall require com-

pliance with any applicable pretreatment requirements and

any requirements under Section 307 of this Act;...”

The BPT identifies the current level of treatment and

is the basis of the current level of control for direct discharges.

BACT improves on the BPT, and it may include operations

or processes not in common use in industry. BCT replaces

BACT for the control of conventional pollutants, such as

biochemical oxygen demand

(BOD), total suspended sol-

ids (TSS), fecal coliform, and

pH

. Details such as the amount

of constituents, and the chemical, physical, and biological

characteristics of pollutants, as well as the degree of effluent

reduction attainable through the application of the selected

technology can be found in the development documents

published by the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA). These development documents cover different in-

dustrial categories such as diary products processing, soap

and

detergents

manufacturing, meat products, grain mills,

canned and preserved fruits and vegetables processing, and

asbestos

manufacturing.

In accordance with Section 304(b) of the Clean Water

Act, the factors to be taken into account in assessing the

BPT include the total cost of applying the technology in

relation to the effluent reductions to the results achieved

from such an application, the age of the equipment and

facilities involved, the process employed, the engineering

123

aspects of applying various types of control technologies and

process changes, and calculations of environmental impacts

other than

water quality

(including energy requirements).

As far as evaluating the BCT is concerned, the factors are

mostly the same. By they include consideration of the reason-

ableness of the relationship between the costs of attaining

a reduction in effluents and the benefits derived from that

reduction, and the comparison of the cost and level of reduc-

tion of such pollutants from the discharge from publicly

owned treatment works to the cost and level of reduction

of such pollutants from a class or category of industrial

sources. Control technologies may include in-plant control

and preliminary treatment, and end-of-pipe treatment, ex-

amples of which are

water conservation

and

reuse

, raw

materials substitution, screening, multimedia

filtration

, and

activated

carbon absorption

.

[James W. Patterson]

Beta particle

An electron emitted by the nucleus of a radioactive atom.

The beta particle is produced when a

neutron

within the

nucleus decays into a proton and an electron. Beta particles

have greater penetrating power than alpha particles but less

than x-ray or gamma rays. Although beta particles can pene-

trate skin, they travel only a short distance in tissue. Beta

rays pose relatively little health hazard, therefore, unless they

are ingested into the body. Naturally radioactive materials

such as potassium-40, carbon-14, and strontium-90 emit

beta particles, as do a number of synthetic radioactive materi-

als. See also Radioactivity

Beyond Pesticides

Founded in 1981, Beyond Pesticides (originally called the

National Coalition Against the Misuse of Pesticides) is

a non-profit, grassroots network of groups and individuals

concerned with the dangers of pesticides. Members of

Beyond Pesticides include individuals, such as “victims” of

pesticides, physicians, attorneys, farmers and farmworkers,

gardeners, and former chemical company scientists, as well

as health, farm, consumer, and church groups. All want

to limit

pesticide

use through Beyond Pesticides, which

publishes information on pesticide hazards and alternatives,

monitors and influences legislation on pesticide issues, and

provides seed grants and encouragement to local groups

and efforts.

Administrated by a 15-member board of directors and

a small full-time staff, including a toxicologist and an ecolo-

gist, Beyond Pesticides is now the most prominent organiza-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bhopal, India

tion dealing with the pesticide issue. It was established on

the premise that much is unknown about the toxic effects

of pesticides and the extent of public exposure to them.

Because such information is not immediately forthcoming,

members of Beyond Pesticides believe the only available way

of reducing both known and unknown risks is by limiting

or eliminating pesticides. The organization takes a dual-

pronged approach to accomplish this. First, Beyond Pesti-

cides draws public attention to the risks of conventional

pest

management; second, it promotes the least-toxic alternatives

to current pesticide practices.

An important part of Beyond Pesticides’s overall pro-

gram is the Center for Community Pesticide and Alterna-

tives Information. The Center is a clearinghouse of informa-

tion, providing a 2,000-volume library about pest control,

chemicals

, and pesticides. To concerned individuals it sells

inexpensive brochures and booklets, which cover topics such

as alternatives to controlling specific pests and chemicals;

the risks of pesticides in schools, to food, and in reproduc-

tion; and developments in the

Federal Insecticide, Fungi-

cide and Rodenticide Act

(FIFRA), the national law gov-

erning pesticide use and registration in the United States.

Through the Center Beyond Pesticides also publishes Pesti-

cides and You (PAY) five times a year. It is a newsletter sent

to approximately 4,500 people, including Beyond Pesticides

members, subscribers, and members of Congress. The Cen-

ter also provides direct assistance to individuals through

access to Beyond Pesticides’s staff ecologist and toxicologist.

In 1991 Beyond Pesticides also established the Local

Environmental Control Project after the Supreme Court

decision affirming local communities’ rights to regulate pes-

ticide use. Although Beyond Pesticides supported bestowing

local control over pesticide use, it needed a new program

to counteract the subsequent mobilization of the pesticide

industry to reverse the Supreme Court decision. The Local

Environmental Control Project campaigns first to preserve

the right accorded by the Supreme Court decision and sec-

ond to encourage communities to take advantage of this

right.

Beyond Pesticides marked its tenth anniversary in

1991 with a forum entitled “A Decade of Determination:

A Future of Change.” It included workshops on

wildlife

and

groundwater

protection,

cancer risk assessment

,

and the implications of GATT and free trade agreements.

Beyond Pesticides has also established the annual National

Pesticide Forum. Through such conferences, its aid to vic-

tims and groups, and its many publications, Beyond Pesti-

cides above all encourages local action to limit pesticides

and change the methods of controlling pests.

[Andrea Gacki]

124

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Beyond Pesticides, 701 E Street, SE, Suite 200, Washington, D.C. USA

20003 (202) 543-5450, Fax: (202) 543-4791, Email: info@beyond

pesticides.org, <http://www.beyondpesticides.org>

Bhopal, India

On December 3, 1984, one of the world’s worst industrial

accidents occurred in Bhopal, India. Along with Three Mile

Island and Chernobyl, Bhopal stands as an example of the

dangers of industrial development without proper attention

to

environmental health

and safety.

A large industrial and urban center in the state of

Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal was the location of a plant owned

by the American chemical corporation, Union Carbide, Inc.

and its Indian subsidiary, Union Carbide India, Ltd. The

plant manufactured pesticides, primarily the

pesticide

car-

baryl (marketed under the name Sevin), which is one of the

most widely used carbamate class pesticides in the United

States and throughout the world. Among the intermediate

chemical compounds used together to manufacture Sevin is

methyl isocyanate (MIC)—a lethal substance that is reactive,

toxic, volatile, and flammable. It was the uncontrolled release

of MIC from a storage tank in the Bhopal facility that caused

the death of 5,000 people, seriously injured another 20,000

and affected an estimated 200,000 people. The actual num-

ber of casualties remains unknown; many believe the num-

bers cited above to be serious underestimates.

MIC (CH3-N=C=O) is highly volatile and has a boil-

ing point of 89°F (39.1°C). In the presence of trace amounts

of impurities such as water or metals, MIC reacts to generate

heat, and if the heat is not removed, the chemical begins to

boil violently. If relief valves, cooling systems and other safety

devices fail to operate in a closed storage tank, the pressure

and heat generated may be sufficient to cause a release of MIC

into the

atmosphere

. Because the vapor is twice as heavy as

air, the vapors if released remain close to the ground where

they can do the most damage, drifting along prevailing wind

patterns. As set by the Occupational Health and Safety Ad-

ministration (OSHA), the standards for exposure to MIC are

set at 0.02 ppm over an eight-hour period. The immediate

effects of exposure, inhalation and ingestion of MIC at high

concentrations (above 2 ppm) are burning and tearing of the

eyes, coughing, vomiting, blindness, massive trauma of the

gastrointestinal tract, clogging of the lungs and suffocation of

bronchial tubes. When not immediately fatal, the long-term

health consequences include permanent blindness, perma-

nently impaired lung functioning, corneal ulcers, skin dam-

age, and potential

birth defects

.

Many explanations for the disaster have been ad-

vanced, but the most widely accepted theory is that trace

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bhopal, India

amounts of water entered the MIC storage tank and initiated

the hydrolysis reaction, which was followed by MIC’s spon-

taneous reactions. The plant was not well designed for safety,

and maintenance was especially poor. Four key safety factors

should have contained the reaction, but it was later discov-

ered that they were all inoperative at the time of the accident.

The refrigerator that should have slowed the reaction by

cooling the chemical was shut off, and, as heat and pressure

built up in the tank, the relief valve blew. A vent gas scrubber

designed to neutralize escaping gas with caustic soda failed

to work. Also, the flare tower that would have burned the

gas to harmless by-products was under repair. Yet even if

all these features had been operational, subsequent investiga-

tions found them to be poorly designed and insufficient for

the capacity of the plant. Once the runaway reaction started,

it was virtually impossible to contain.

The poisonous cloud of MIC released from the plant

was carried by the prevailing winds to the south and east of

the city—an area populated by highly congested communi-

ties of poorer people, many of whom worked as laborers at

the Union Carbide plant and other nearby industrial facili-

ties. Released at night, the silent cloud went undetected by

residents who remained asleep in their homes, thus possibly

ensuring a maximal degree of exposure. Many hundreds died

in their sleep, others choked to death on the streets as they

ran out in hopes of escaping the lethal cloud. Thousands

more died in the following days and weeks. The Indian

government and numerous volunteer agencies organized a

massive relief effort in the immediate aftermath of the disas-

ter consisting of emergency medical treatment, hospital facil-

ities, and supplies of food and water. Medical treatment was

often ineffective, for doctors had an incomplete knowledge

of the toxicity of MIC and the appropriate course of action.

In the weeks following the accident, the financial, legal

and political consequences of the disaster unfolded. In the

United States Union Carbide’s stock dipped 25% in the

week immediately following the event. Union Carbide India

Ltd. (UCIL) came forward and accepted moral responsibility

for the accident, arranging some interim financial compensa-

tion for victims and their families. However its parent com-

pany, Union Carbide Inc., which owned 50.9% of UCIL,

refused to accept any legal responsibility for their subsidiary.

The Indian government and hundreds of lawyers on both

sides pondered issues of liability and the question of a settle-

ment. While Union Carbide hoped for out-of-court settle-

ments or lawsuits in the Indian courts, the Indian govern-

ment ultimately decided to pursue class action suits on behalf

of the victims in the United States courts in the hope of

larger settlements. The United States courts refused to hear

the case, and it was transferred to the Indian court system.

Warren Anderson, then chairman of Union Carbide, refused

to appear in Indian court. The case is still under litigation

125

and the interim compensation set aside has reached only a

fraction of the victims.

The disaster in Bhopal has had far-reaching political

consequences in the United States. A number of Congres-

sional hearings were called and the

Environmental Protec-

tion Agency

(EPA) and OSHA initiated inspections and

investigations. A Union Carbide plant in McLean, Virginia,

that uses processes and products similar to those in Bhopal

was repeatedly inspected by officials. While no glaring defi-

ciencies in operation or maintenance were found, it was

noted that several small leaks and spills had occurred at the

plant in previous years that had gone unreported. These

added weight to growing national concern about workers’

right-to-know

provisions and emergency response capabili-

ties. In the years following the Bhopal accident, both state

and federal environmental regulations were expanded to in-

clude mandatory preparedness to handle spills and releases

on land, water, or air. These regulations include measures

for emergency response such as communication and coordi-

nation with local health and law enforcement facilities, as

well as community leaders and others. In addition, employers

are now required to inform any workers in contact with

hazardous materials of the nature and types of hazards to

which they are exposed; they are also required to train them

in emergency health and safety measures.

The disaster at Bhopal raises a number of critical issues

and highlights the wide gulf between developed and devel-

oping countries in regard to design and maintenance stan-

dards for health and safety. Management decisions allowed

the Bhopal plant to operate in an unsafe manner and for a

shanty-town to develop around its perimeter without appro-

priate emergency planning. The Indian government, like

many other developing nations in need of foreign invest-

ment, appeared to sacrifice worker safety in order to attract

and keep Union Carbide and other industries within its

borders. While a number of environmental and occupational

health and safety standards existed in India before the acci-

dent, their inspection and enforcement was cursory or non-

existent. Often understaffed, the responsible Indian regula-

tory agencies were rife with corruption as well. The Bhopal

disaster also raised questions concerning the moral and legal

responsibilities of American companies abroad, and the will-

ingness of those corporations to apply stringent United

States safety and environmental standards to their operations

in the

Third World

despite the relatively free hand given

them by local governments.

Although worldwide shock at the Bhopal accident has

largely faded, the suffering of many victims continues. While

many national and international safeguards on the manufac-

ture and handling of hazardous

chemicals

have been insti-

tuted, few expect that lasting improvements will occur in

developing countries without a gradual recognition of the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bikini atoll

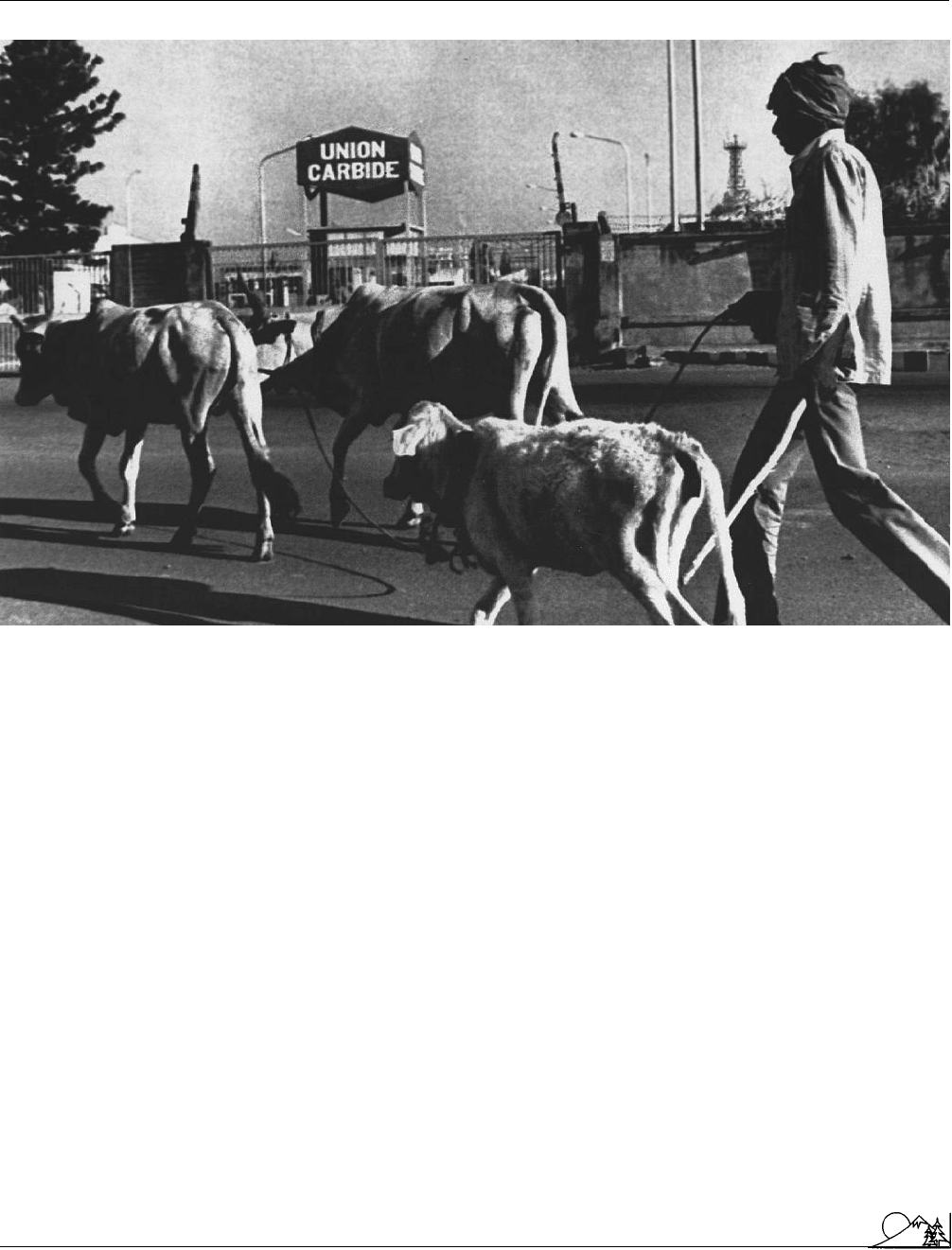

Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India. (Corbis-Bettmann. Reproduced by permission.)

economic and political values of stringent health and safety

standards.

[Usha Vadagiri]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Diamond, A. The Bhopal Chemical Leak. San Diego, CA: Lucent, 1990.

Kurzman, D. A Killing Wind: Inside the Bhopal Catastrophe. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1987.

P

ERIODICALS

“Bhopal Report.” Chemical and Engineering News (February 11, 1985):

14–65.

Bikini atoll

The primary objective of the Manhattan Project during

World War II was the creation of a

nuclear fission

or

atomic bomb. Even before that goal was accomplished in

1945, however, some nuclear scientists were thinking about

126

the next step in the development of

nuclear weapons

,a

fusion or

hydrogen

bomb.

Progress on a fusion bomb was slow. Questions were

raised about the technical possibility of making such a bomb,

as well as the moral issues raised by the use of such a destruc-

tive weapon. But the detonation of an atomic bomb by the

Soviet Union in 1949 placed the fusion bomb in a new

perspective. Concerned that the United States was falling

behind in its arms race with the Soviet Union, President

Harry S. Truman authorized a full-scale program for the

development of a fusion weapon.

The first test of a fusion device occurred on October

31, 1952, at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands in the

Pacific Ocean. This was followed by a series of six more

tests, code-named “Operation Castle,” at Bikini Atoll in

1954. Two years later, on May 20, 1956, the first

nuclear

fusion

bomb was dropped from an airplane over Bikini Atoll.

Bikini Atoll had been selected in late 1945 as the site

for a number of tests of fission weapons, to experiment with

different designs for the bomb and to test its effects on ships

and the natural

environment

.