Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Biomass fuel

The efficiency with which biomass may be converted

to ethanol or other convenient liquid or gaseous fuels is a

major concern. Conversion generally requires appreciable

energy. If an excessive amount of expensive fuel is used in

the process, costs may be prohibitive. Corn (Zea mays) has

been a particular focus of efficiency studies. Inputs for the

corn system include energy for production and application

of

fertilizer

and

pesticide

, tractor fuel, on-farm electricity,

etc., as well as those more directly related to fermentation.

A recent estimate puts the industry average for energy output

at 133% of that needed for production and processing. This

net energy gain of 33% includes credit for co-products such

as corn oil and protein feed as well as the energy value

of ethanol. The most efficient production and conversion

systems are estimated to have a net energy gain of 87%.

Although it is too soon to make an accurate assessment of

the net energy gain for cellulose-based ethanol production,

it has been estimated that a net energy gain of 145% is

possible.

Biomass-derived gaseous and liquid fuels share many

of the same characteristics as their fossil fuel counterparts.

Once formed, they can be substituted in whole or in part

for petroleum-derived products.

Gasohol

, a mixture of 10%

ethanol in

gasoline

, is an example. Ethanol contains about

35% oxygen, much more than gasoline, and a gallon contains

only 68% of the energy found in a gallon of gasoline. For

this reason, motorists may notice a slight reduction in gas

mileage when burning gasohol. However, automobiles burn-

ing mixtures of ethanol and gasoline have a lower exhaust

temperature. This results in reduced toxic emissions, one

reason that clean air advocates often favor gasohol use in

urban areas.

Biomass is called as a renewable resource since green

plants are essentially solar collectors that capture and store

sunlight in the form of chemical energy. Its renewability

assumes that source plants are grown under conditions where

yields are sustainable over long periods of time. Obviously,

this is not always the case, and care must be taken to insure

that growing conditions are not degraded during biomass

production.

A number of studies have attempted to estimate the

global potential of biomass energy. Although the amount

of sunlight reaching the earth’s surface is substantial, less

than a tenth of a percent of the total is actually captured

and stored by plants. About half of it is reflected back to

space. The rest serves to maintain global temperatures at

life-sustaining levels. Other factors that contribute to the

small fraction of the sun’s energy that plants store include

Antarctic and Arctic zones where little

photosynthesis

oc-

curs, cold winters in temperate belts when plant growth is

impossible, and lack of adequate water in

arid

regions. The

global total net production of biomass energy has been esti-

147

mated at 100 million megawatts per year per year. Forests

and woodlands account for about 40% of the total, and

oceans about 35%. Approximately 1% of all biomass is used

as food by humans and other animals.

Soil

requires some organic content to preserve struc-

ture and fertility. The amount required varies widely de-

pending on

climate

and soil type. In tropical rain forests,

for instance, most of the nutrients are found in living and

decaying vegetation. In the interests of preserving photosyn-

thetic potential, it is probably inadvisable to remove much

if any organic matter from the soil. Likewise, in sandy soils,

organic matter is needed to maintain fertility and increase

water retention. Considering all the constraints on biomass

harvesting, it has been estimated that about six million

MWyr/yr of biomass are available for energy use. This repre-

sents about 60% of human society’s total energy use and

assumes that the planet is converted into a global garden

with a carefully managed “photosphere.”

Although biomass fuel potential is limited, it provides

a basis for significantly reducing society’s dependence on

non-renewable reserves. Its potential is seriously diminished

by factors that degrade growing conditions either globally

or regionally. Thus, the impact of factors like global warming

and

acid rain

must be taken into account to assess how

well that potential might eventually be realized. It is in this

context that one of the most important aspects of biomass

fuel should be noted. Growing plants remove

carbon

dioxide

from the

atmosphere

that is released back to the atmo-

sphere when biomass fuels are used. Thus the overall concen-

tration of atmospheric carbon dioxide should not change,

and global warming should not result. Another environmen-

tal advantage arises from the fact that biomass contains much

less sulfur than most fossil fuels. As a consequence, biomass

fuels should reduce the impact of acid rain.

[Douglas C. Pratt]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Hall, C. W. Biomass as an Alternative Fuel. Rockville, Maryland: Govern-

ment Institutes, Inc., 1981.

Ha

¨

fele, W. Energy in a Finite World: A Global Systems Analysis. Great

Britain: Harper & Row Ltd., Inc., 1981.

Lieth, H. F. H. Patterns of Primary Production in the Biosphere. Stroudsburg,

Pennsylvania: Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross, Inc., 1981.

Morris, D. M., & I. Ahmed, How Much Energy Does It Take to Make a Gallon

of Ethanol? Washington D.C.: Institute for Local Self-Reliance, 1992.

Smil, V. Biomass Energies: Resources, Links, Constraints. New York: Plenum

Press, 1983.

Stobaugh, R. & D. Yergin, eds. Energy Future: Report of the Energy Project

at the Harvard Business School. New York: Random House, Inc., 1979.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Biome

Biome

A large terrestrial

ecosystem

characterized by distinctive

kinds of plants and animals and maintained by a distinct

climate

and

soil

conditions. To illustrate, the

desert

biome

is characterized by low annual rainfall and high rates of

evaporation, resulting in dry environmental conditions.

Plants and animals that thrive in such conditions include

cacti, brush, lizards, insects, and small rodents. Special adap-

tations, such as waxy plant leaves, allow organisms to survive

under low moisture conditions. Other examples of biomes

include

tropical rain forest

, arctic

tundra

,

grasslands

,

temperate

deciduous forest

,

coniferous forest

, tropical

savanna

, and Mediterranean

chaparral

.

Biomonitoring

see

Bioindicator

Biophilia

The term biophilia was coined by the American biologist,

Edward O. Wilson

(1929–), to mean “the innate tendency

[of human beings] to focus on life and lifelike processes”

and “connections that human beings subconsciously seek

with the rest of life.” Wilson first used the word in 1979 in

an article published in the New York Times Book Review,

and then in 1984 he wrote a short book (157 pages) that

explored the notion in more detail.

Clearly, humans have coexisted with other

species

throughout our evolutionary history. In Wilson’s view, this

relationship has resulted in humans developing an innate,

genetically based, or “hard-wired” need to be close to other

species and to be empathetic to their needs. The presumed

relationship is reciprocal, meaning other animals are also to

varying degrees empathetic with the needs of humans. The

biophilia hypothesis seems intuitively reasonable, although

it is likely impossible that it could ever be proven universally

correct. For instance, while many people may feel and express

biophilia, some people may not.

There is a considerable body of psychological and med-

ical evidence in support of the notion of biophilia, although

most of it is anecdotal. There are, for example, many observa-

tions of sick or emotionally distressed people becoming well

more quickly when given access to a calming natural

envi-

ronment

, or when comforted by such pets as dogs and cats.

There are also more general observations that many people

are more comfortable in natural environments than in artifi-

cial ones — it can be much more pleasant to sit in a garden,

for instance, than in a windowless room. The aesthetics and

comfort of that room can, however, be improved by hanging

pictures of animals or landscapes, by watching a nature show

148

on television, or by providing a window that looks out onto

a natural scene.

Wilson is a leading environmentalist and a compelling

advocate of the need to conserve the threatened

biodiversity

of the world, such as imperiled natural ecosystems and

en-

dangered species

. To a degree, his notion of biophilia

provides a philosophical justification for

conservation

ac-

tions, by suggesting emotional and even spiritual dimensions

to the human relationship with other species and the natural

world. If biophilia is a real phenomenon and an integral part

of what it is to be human, then our affinity for other species

means that willful actions causing endangerment and

extinc-

tion

can be judged to be wrong and even immoral. Our innate

affinity for other species provides an intrinsic justification for

doing them no grievous harm, and in particular, for avoiding

their extinction. It provides a justification for enlightened

stewardship of the natural world.

Humans also utilize animals in agriculture (we raise

them as food), in research, and as companions. Ethical con-

siderations derived from biophilia provides a rationale for

treating animals as well as possible in those uses, and may

even be used to justify

vegetarianism

and anti-vivisec-

tionism.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Kellert, S.R. and E.O. Wilson, editors. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington,

DC: Island Press, 1993.

Wilson, E.O. Biophilia. The Human Bond With Other Species. Harvard,

MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

O

THER

Arousing Biophilia: A Conversation with E.O. Wilson. EnviroArts: Orion On-

line. <http://arts.envirolink.org/interviews_and_conversations/EOWilson.

html>

Bioregional Project

Based in the Ozark Mountains in Missouri, the Bioregional

Project (BP) was founded in 1982 to promote the aims and

interests of the bioregional movement in North America.

Consisting primarily of a resource center designed to show

people how to “come back home to Earth,” the Bioregional

Project is part of the international campaign to reshape

culture and society according to ecological principles: “We

work for the honor, protection and healing of the Earth,

the Earth’s people, and all the Earth’s life.”

A bioregion is what the group calls a “life region,” an

area determined by natural rather than historical or political

boundaries. It is distinguished by the character of the

flora

and

fauna

, by the landforms, the types of rocks and soils,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bioregional Project

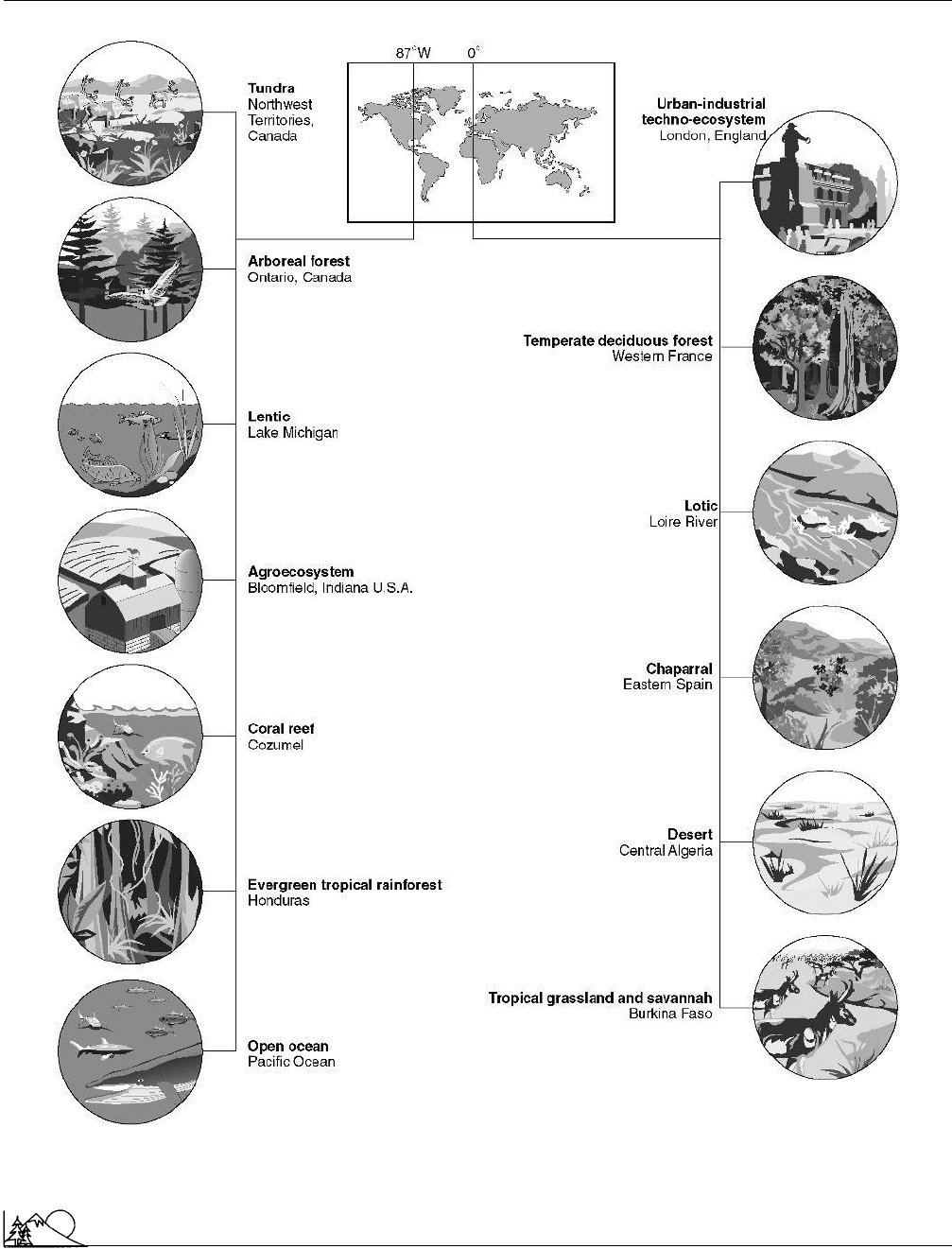

Different biomes worldwide.

149

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bioregionalism

the

climate

in general, and by human habitation as it relates

to this

environment

. The Bioregional Project emphasizes

the natural logic of these boundaries, and it promotes the

development of social and political institutions that take into

account the interrelatedness of everything within them. They

are working to increase the awareness that bioregions are

“living, self-organizing systems,” and they value humanity

as one

species

among many. The Bioregional Project traces

the roots of the movement to native and

indigenous peo-

ples

and the “oldest Earth traditions.” The group believes

that ecological laws and principles form the basis of society

and that the future survival of humanity depends on their

ability to cooperate with the environment.

The Bioregional Project and the bioregional move-

ment as a whole have strong ties to the international Green

Movement, although bioregionalists consider themselves

more “ecologically-centered.” The

Greens

are oriented to

urban areas, and they work for change in traditional political

structures, operating within legislative as opposed to bioregi-

onal systems. The chief organizing tool of the bioregional

movement is a model known as “the bioregional congress”

or “green congress,” where participants share information,

develop ecological strategies, and draft planning programs

and platform statements. The Bioregional Project convened

the first bioregional congress in 1980 as the Ozark Commu-

nity Congress (OACC), and it has since influenced both

bioregional and green organizing throughout North

America. The Project coordinated the first North American

Bioregional Congress in 1984, an international assembly

attended by over 200 people representing 130 organizations.

In addition to the assistance it provides for “those

organizing bioregionally,” the Bioregional Project also pub-

lishes books and pamphlets on

bioregionalism

and

ecol-

ogy

. The organization sponsors lectures and educational

presentations on these subjects as well. It supports research

and lends technical assistance in a variety of areas from

community economic development to

recycling

,

sustain-

able agriculture

, and forest protection. It is a subsidiary of

the Ozarks Resource Center. Contact: Bioregional Project,

Box 3, Brixley, MO 65618. telephone(417) 679 4773

[Douglas Smith]

Bioregionalism

Drawing heavily upon the cultures of

indigenous peoples

,

bioregionalism is a philosophy of living that stresses harmony

with

nature

and the integration of humans as part of the

natural

ecosystem

. The keys to bioregionalism involve

learning to live off the land, without damaging the

environ-

ment

or relying on heavy industrial machines or products.

150

Bioregionalists believe that if the relationship between nature

and humans improves, the society as a whole will benefit.

Environmentalists who practice this philosophy

“claim” a bioregion or area. For example, one’s place might

be a

watershed

, a small mountain range, a particular area

of the coast, or a specific

desert

. To develop a connection

to the land and a

sense of place

, bioregionalists try to

understand the natural history of the area as well as how it

supports human life. For example, they study the plants and

animals that inhabit the region, the geological features of

the land, as well as the cultures of the people who live or

have lived in the area.

Bioregionalism also stresses community life where par-

ticipation, self-determination, and local control play impor-

tant roles in protecting the environment. Various bioregional

groups exist throughout the United States, ranging from the

Gulf of Maine to the Ozark Mountains to the San Francisco

Bay area. A North American Bioregional Congress loosely

coordinates the bioregional movement.

[Christopher McGrory Klyza]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Andruss, V., et al. Home! A Bioregional Reader. Philadelphia: New Society

Publishers, 1990.

Sale, K. Dwellers in the Land: The Bioregional Vision. San Francisco: Sierra

Club Books, 1985.

Snyder, G. The Practice of the Wild. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1990.

Bioremediation

A number of processes for remediating contaminated soils

and

groundwater

based on the use of

microorganisms

to

convert contaminants to less hazardous substances. Most

commercial bioremediation processes are intended to convert

organic substances to

carbon dioxide

and water, although

processes for addressing metals are under development.

Many bacteria ubiquitously found in soils and groundwater

are able to biodegrade a range of organic compounds. Com-

pounds found in

nature

, and ones similar to those, such as

petroleum hydrocarbons

, are most readily biodegraded

by these bacteria. Bioremediation of chlorinated solvents,

polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)s, pesticides, and many mu-

nitions compounds, while of great interest, is more difficult

and has thus been much slower to reach commercialization.

In most bioremediation processes the bacteria use the

contaminant as a food and energy source and thus survive

and grow in numbers at the expense of the contaminant. In

order to grow new cells, bacteria, like other biological

spe-

cies

, require numerous minerals as well as

carbon

sources.

These minerals are typically present in sufficient amounts

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bioremediation

except for

phosphorus

and

nitrogen

, which are commonly

added during bioremediation. If contaminant molecules are

to be transformed, species called electron acceptors must

also be present. By far the most commonly used electron

acceptor is oxygen. Other electron acceptors include nitrate,

sulfate, carbon dioxide, and iron. Processes that use oxygen

are called

aerobic

biodegradation. Processes that use other

electron acceptors are commonly lumped together as

anaer-

obic

biodegradation.

The vast majority of commercial bioremediation pro-

cesses use aerobic biodegradation and thus include some

method for providing oxygen. The amount of oxygen that

must be provided depends not only on the mass of contami-

nant present but also on the extent of conversion of the

contaminants to carbon dioxide and water, other sources

of oxygen, and the extent to which the contaminants are

physically removed from the soils or groundwater. Typically,

designs are based on adding two to three pounds of oxygen

for each pound of

biodegradable

contaminant.

The processes generally include the addition of

nutri-

ent

(nitrogen and phosphorus) sources. The amount of ni-

trogen and phosphorus that must be provided is quite vari-

able and frequently debated. In general, this amount is less

than the 100:10:1 ratio of carbon to nitrogen to phosphorus

of average cell compositions. It is also important to maintain

the

soil

or groundwater

pH

near neutral (pH 6–8.5), mois-

ture levels at or above 50% of

field capacity

, and tempera-

tures between 39°F (4°C) and 95°F (35°C), preferably be-

tween 68°F (20°C) and 86°F (30°C).

Bioremediation can be applied in situ and ex situ by

several methods. Each of these processes are basically engi-

neering solutions to providing oxygen (or alternate electron

acceptors) and possibly, nutrients to the contaminated soils,

which already contain the bacteria. The addition of other

bacteria is not typically needed or beneficial.

In situ processes have the advantage of causing mini-

mal disruption to the site and can be used to address contami-

nation under existing structures. In situ bioremediation to

remediate aquifers contaminated with petroleum hydrocar-

bons such as

gasoline

, was pioneered in the 1970s and early

1980s by Richard L. Raymond and coworkers. These systems

used groundwater recovery

wells

to capture contaminated

water which was treated at the surface and reinjected after

amendment with nutrients and oxygen. The nutrients con-

sisted of ammonium chloride and phosphate salts and some-

times contained magnesium, manganese, and iron salts. Ox-

ygen was introduced by sparging (bubbling) air into the

reinjection water. As the injected water swept through the

aquifer

, oxygen and nutrients were carried to the contami-

nated soils and groundwater where the indigenous bacteria

converted the hydrocarbons to new cell material, carbon

dioxide, and water. Variations of this technology include the

151

use of

hydrogen

peroxide as a source of oxygen and direct

injection of air into the aquifer.

Bioremediation of soils located between the ground

surface and the

water table

is most commonly practiced

through

bioventing

. In this method, oxygen is introduced

into the contaminated soils by either injecting air or ex-

tracting air from wells. The systems used are virtually the

same as for vapor extraction. The major difference is in

mode of operation and in the fact that nutrients are some-

times added by percolating nutrient amended water through

the soil from the ground surface or buried horizontal pipes.

Systems designed for bioremediation operate at low air flow

rates to replace oxygen consumed during biodegradation and

to minimize physical removal of volatile contaminants.

Bioremediation can be applied to excavated soils by

landfarming, soil cell techniques, or in soil slurries. The

simplest method is landfarming. In this method soils are

spread to a depth of 12–18 inches (30–46 cm). Nutrients,

usually commercial fertilizers with high nitrogen and low

phosphorous content, are added periodically to the soils

which are tilled or plowed frequently. In most instances,

the treatment area is prepared by grading, laying down an

impervious layer (clay or a synthetic liner), and adding a

six-inch layer of clean soil or sand. Provisions for treating

rainwater

runoff

are typically required. The frequent tilling

and plowing breaks up soil clumps and exposes the soils and

thus bacteria to air. This method is more suitable for treating

silty and clayey soils than are most of the other methods. It is

not generally appropriate for soils contaminated with volatile

contaminants such as gasoline because vapors can not be

controlled unless the process is conducted within a closed

structure.

Excavated soils can also be treated in cells or piles. A

synthetic liner is placed on a graded area and covered with

sand or gravel to permit collection of runoff water. The

sands or gravel are covered with a

permeable

fabric and

nutrient amended soils are added. Slotted PVC pipe is added

as the pile is built. The soils are covered with a synthetic

liner and the PVC pipes are connected to a blower. Air is

slowly extracted from the soils and, if necessary, treated

before being discharged to the

atmosphere

. This method

requires less room than landfarming and less maintenance

during operations, and can be used to treat volatile contami-

nants because the vapors can be controlled.

Excavated soils can also be treated in soil/water slurries

in either commercial reactors or in impoundments or la-

goons. Soils are separated from oversize materials and mixed

with water, nutrients are added, and the

slurry

is aerated

to provide oxygen. In some cases additional sources of bacte-

ria and/or surfactants are added. These systems are usually

capable of attaining more rapid rates of biodegradation than

other systems but have limited throughput.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Bioremediation

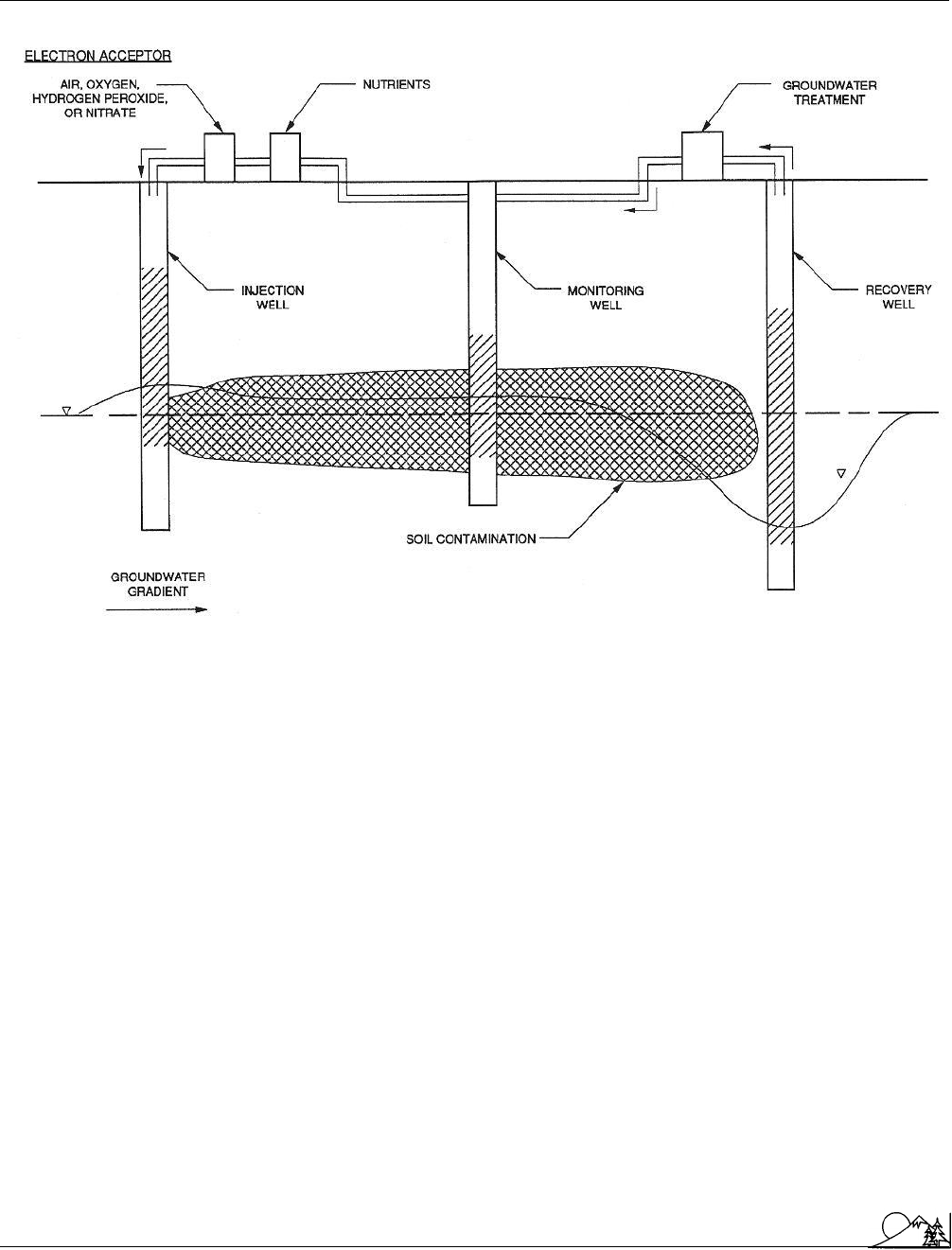

Bioremediation of the saturated zone using hydrogen peroxide in the Raymond process.

Selection and design of a particular bioremediation

method requires that the site be carefully investigated to

define the lateral and horizontal extent of contamination

including the total mass of biodegradable substances. Under-

standing the soil types and distribution and the site

hydro-

geology

is as important as identifying the contaminants and

their distribution in both soils and groundwater. Designing

bioremediation systems requires the integration of microbi-

ology, chemistry, hydrogeology, and engineering.

Bioremediation is generally viewed favorably by regu-

latory agencies and is actively supported by the U. S.

Envi-

ronmental Protection Agency

(EPA). The mostly favor-

able publicity and the perception of bioremediation as a

natural process has led to greater acceptance by the public

compared to other technologies, such as

incineration

.Itis

expected that the use of bioremediation to treat soils and

groundwater contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons

and other readily biodegradable compounds will continue

to grow. Continued improvements in the design and engi-

neering of bioremediation systems will result from the ex-

panding use of bioremediation in a competitive market. It

is anticipated that processes for treating the more recalcitrant

152

organic compounds and metals will become commercial

through greater understanding of microbiology and specific

developments in the isolation of special bacteria and

genetic

engineering

.

[Robert D. Norris]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Chapelle, F. H. Ground-Water Microbiology and Geochemistry. New York:

Wiley, 1993.

Hinchee, R. E., and R. F. Olfenbuttel, eds. In Situ Bioreclamation: Applica-

tions and Investigation for Hydrocarbons and Contaminated Site Remediation.

Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991.

Hinchee, R. E., and R. F. Olfenbuttel, eds. On-Site Bioreclamation: Processes

for Xenobiotic and Hydrocarbon Treatment. Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991.

Matthews, J. E., ed. In Situ Bioremediation of Groundwater and Geological

Materials: A Review of Technologies. Chelsea, MI: Lewis, 1993.

National Research Council. In Situ Bioremediation: When Does It Work?

Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1993.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Biosphere

Biosequence

A sequence of soils that contain distinctly different

soil

horizons because of the influence that vegetation had on the

soils during their development. A typical biosequence would

be the

prairie

soils in a dry

environment

, oak-savannah

soils as a transition zone, and forested soils in a wetter

environment. Prairie soils have dark, thick surface horizons

while forested soils have a thin, dark surface with a light-

colored zone below.

Biosphere

The biosphere is the largest possible earthly organismic com-

munity. It is a terrestrial envelope of life, or the total global

biomass

of living matter. The biosphere incorporates every

individual organism and

species

on the face of the earth—

those that walk on the ground or live in the crevices of rock

and down into the

soil

, those that swim in rivers, lakes, and

oceans, and those that move in and out of the

atmosphere

.

Bios is the Greek word for life; “sphere” is from the

Latin sphaera, which means essentially the “circuit or range

of action, knowledge or influence,” the “place or scene of

action or existence,” the “natural, normal or proper place.”

Combined into biosphere, the two ideas define the normal

global place of existence for all earthly life-forms and, in-

creasingly, a global area of influence and action for humans.

Thinking of the mass of life forms on the earth as the

biosphere also provides an impression of circular, cyclic sys-

tems and suggests a holistic concept of integration and unity.

A Scientific American book on the biosphere described

it as “this thin film of air and water and soil and life no

deeper than ten miles, or one four-hundredth of the earth’s

radius [that] is now the setting of the uncertain history of

man.” G. E. Hutchinson in that same book asked, “What

is it that is so special about the biosphere?” He suggested

that the answer seems to have three parts: “First, it is a

region in which liquid water can exist in substantial quanti-

ties. Second, it receives an ample supply of energy from an

external source, ultimately from the sun. And third, within

it there are interfaces between the liquid, the solid and the

gaseous states of matter.” Both of these might better describe

what LaMont Cole labeled the “ecosphere,” the global eco-

system—the biosphere plus its abiotic

environment

. But

the significance of Hutchinson’s three-part statement is that

those three characteristics of the earth’s surface make it

possible for life to exist. They provide the conditions neces-

sary for the abundant and diverse organisms of the biosphere

to live.

Life began in a very different environment than found

today: the atmosphere, for example, was mostly

methane

,

153

ammonia, and

carbon dioxide

. As life evolved, it changed

the atmosphere (and other abiotic components of the surface

of the earth), transforming it into the present oxygen-rich

mixture of gases vital to life as it now exists. And those life-

forms maintain that critical mixture in a complex, fluctuating

system of global cycles.

The diversity and complexity of the biosphere is stag-

gering. The accumulated human knowledge of its workings

is prodigious, but even more impressive is the immense

ignorance of that complexity. Humans have identified about

1.5 million living members of the biosphere and thus have

some knowledge of at least that many. However, conservative

estimates of the actual number of species begin at 3 or 3.5–

5 million species. Recent and less conservative estimates

range up to a possible 100 million. That means humans are

totally ignorant of anywhere from 50% to as much as 98.5%

of the other members of the earth’s

biological community

.

Their existence is suspected, but they cannot be identified

or their existence documented by even a name.

One of the concerns about large-scale human igno-

rance of the biosphere is that many species might be extin-

guished before they are even known. Human activities, espe-

cially destruction of

habitat

, are increasing the normal rate

of species

extinction

. The diversity of the biosphere may

be diminishing rapidly.

Taxonomically, the biosphere is organized into five

kingdoms: monera, protista,

fungi

, animalia, and plantae,

and a multitude of subsets of these, including the multiple

millions of species mentioned above. G. Piel estimates that

of the 1,200–1,800 billion tons dry weight of the biosphere,

most of it—some 99%—is plant material. All the life-forms

in the other four taxons, including animals and obviously

the five billion-plus humans alive today, are part of that less

than one%.

The biosphere can also be subdivided into biomes: a

biome

incorporates a set of biotic communities within a

particular region exposed to similar climatic conditions and

which have dominant species with similar life cycles, adapta-

tions, and structures. Deserts,

grasslands

, temperate decid-

uous forests, coniferous forests,

tundra

, tropical rain forests,

tropical seasonal forests, freshwater biomes, estuaries,

wet-

lands

, and marine biomes, are examples of specific terrestrial

or aquatic biomes.

Another indication of the complexity of the biosphere

is a measure of the processes that take place within it, espe-

cially the essential processes of

photosynthesis

and

respira-

tion

. The sheer size of the biosphere is indicated by the

amount of biomass present. Vitousek and his colleagues

estimate the net primary production of the earth’s biosphere

as 224.5 petagrams, one petagram being equivalent to 10

15

grams.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Biosphere reserve

The biosphere interacts in constant, intricate ways with

other global systems: the atmosphere, lithosphere, hydro-

sphere, and pedosphere. Maintenance of life in the biosphere

depends on this complex network of biological-biological,

physical-physical, and biological-physical interactions. All

the interactions are mediated by an equally complex system

of positive and negative feedbacks—and the total makes

up the dynamics of the whole system. Since each and all

interpenetrate and react on each other constantly, outlining

a global

ecology

is a major challenge.

Normally biospheric dynamics are in a rough balance.

The

carbon cycle

, for example, is usually balanced between

production and

decomposition

, the familiar equation of

photosynthesis and respiration. As Piel notes: “The two

planetary cycles of photosynthesis and

aerobic metabolism

in the biomass not only secure renewal of the biomass but also

secure the steady-state mixture of gases in the atmosphere.

Thereby, these life processes mediate the inflow and outflow

of

solar energy

through the system; they screen out lethal

radiation, and they keep the temperature of the planet in

the narrow range compatible with life.” But human activities,

especially the

combustion

of

fossil fuels

, contribute to in-

creases in

carbon

dioxide, distorting the balance and in

the process changing other global relationships such as the

nature

of incoming and out-going radiation and differen-

tials in temperature between poles and tropics.

If humans are to better understand the biosphere,

many more studies must be undertaken on many levels. A

number of levels of biological integration must be recognized

and analyzed, each with different properties and each offer-

ing scholars special problems and special insights. The total-

ity of the biosphere can be broken down in many different

ways, but life extends from the single cell to the totality of

the globe. Though biologists usually define their disciplines

within the bounds of one level and though they may study

only one level, scholars should recognize context, the full

range of levels and the interactions between them.

Humans are, of course, one of the species that make

up the living biosphere. Homo sapiens fits into the Linnean

hierarchy on the primate branch. Using that hierarchy as

a connective device, humans may take a first step toward

understanding how they relate to the rest of the inhabitants

of the biosphere, down to the most remote known species.

Humans are without doubt the dominant species in

the biosphere. The transformation of radiant energy into

useable biological energy is increasingly being diverted by

humans to their own use. A common estimate is that humans

are now diverting huge amounts of the net primary produc-

tion of the globe to their own use: perhaps 40% of terrestrial

production and close to 25% of all production is either

utilized or wasted through human activity. Net primary pro-

duction is defined as the amount of energy left after sub-

154

tracting the respiration of primary producers, or plants, from

the total amount of energy. It is the total amount of “food”

available from the process of photosynthesis—the amount

of biomass available to feed organisms, such as humans, that

do not acquire food through photosynthesis.

Humans are displacing their neighbors in the bio-

sphere through a multitude of activities: conversion of natu-

ral systems to agriculture, direct consumption of plants, con-

sumption of plants by livestock, harvesting and conversion

of forests,

desertification

, and many, many others. The

biosphere is the source of all good: humans are an integral

part of the biosphere and depend on its functioning for their

well-being, for their very lives.

[Gerald L. Young]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bradbury, I. K. The Biosphere. London/New York: Belhaven Press, 1991.

Clark, W. C., and R. E. Munn, eds. Sustainable Development of the Biosphere.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Piel, G. “The Biosphere.” In Only One World: Our Own to Make and to

Keep. New York: W. H. Freeman, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Salthe, S. N. “The Evolution of the Biosphere: Towards a New Mythology.”

World Futures 30 (1990): 53–67.

Vitousek, P. M., et al. “Human Appropriation of the Products of Photosyn-

thesis.” BioScience 36 (1986): 368–373.

Biosphere reserve

A

biosphere

reserve is an area of land recognized and pre-

served for its ecological significance. Ideally biosphere re-

serves contain undisturbed, natural environments that repre-

sent some of the world’s important ecological systems and

communities. Biosphere reserves are established in the inter-

est of preserving the genetic diversity of these ecological

zones, supporting research and education, and aiding local,

sustainable development

. Official declaration and inter-

national recognition of biosphere reserve status is intended

to protect ecologically significant areas from development

and destruction. Since 1976 an international network of

biosphere reserves has developed, with the sanction of the

United Nations. Each biosphere reserve is proposed, re-

viewed, and established by a national biosphere reserve com-

mission in the home country under United Nations guide-

lines. Communication among members of the international

biosphere network helps reserve managers share data and

compare management strategies and problems.

The idea of biosphere reserves first gained interna-

tional recognition in 1973, when the United Nations Educa-

tional and Scientific Organization (UNESCO)’s

Man and

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Biosphere reserve

the Biosphere Program

(MAB) proposed that a worldwide

effort be made to preserve islands of the world’s living re-

sources from

logging

, mining, urbanization, and other envi-

ronmentally destructive human activities. The term derives

from the ecological word “biosphere,” which refers to the

zone of air, land, and water at the surface of the earth that

is occupied by living organisms. Growing concern over the

survival of individual

species

in the 1970s and 1980s led

increasingly to the recognition that

endangered species

could not be preserved in isolation. Rather, entire ecosys-

tems, extensive communities of interdependent animals and

plants, are needed for threatened species to survive. Another

idea supporting the biosphere reserve concept was that of

genetic diversity. Generally ecological systems and commu-

nities remain healthier and stronger if the diversity of resi-

dent species is high. An alarming rise in species extinctions

in recent decades, closely linked to rapid

natural resources

consumption, led to an interest in genetic diversity for its

own sake. Concern for such ecological principles as these

led to UNESCO’s proposal that international attention be

given to preserving the earth’s ecological systems, not just

individual species.

The first biosphere reserves were established in 1976.

In that year, eight countries designated a total of 59 biosphere

reserves representing ecosystems from

tropical rain forest

to temperate sea coast. The following year 22 more countries

added another 72 reserves to the United Nations list, and

by 2002 there was a network of 408 reserves established in

94 different countries.

Like national parks,

wildlife

refuges, and other

na-

ture

preserves, the first biosphere reserves aimed to protect

the natural

environment

from surrounding populations, as

well as from urban or international exploitation. To a great

extent this idea followed the model of United States national

parks, whose resident populations were removed so that

parks could approximate pristine, undisturbed natural envi-

ronments.

But in smaller, poorer, or more crowded countries than

the United States, this model of the depopulated reserve

made little sense. Around most of the world’s nature pre-

serves, well-established populations—often indigenous or

tribal groups—have lived with and among the area’s

flora

and

fauna

for generations or centuries. In many cases, these

groups exploit local resources—gathering nuts, collecting

firewood, growing food—without damaging their environ-

ment. Sometimes, contrary to initial expectations, the activ-

ity of

indigenous peoples

proves essential in maintaining

habitat

and species diversity in preserves. Furthermore, local

residents often possess an extensive and rare understanding

of plant habitat and animal behavior, and their skills in using

resources are both valuable and irreplaceable. At the very

least, the cooperation and support of local populations is

155

essential for the survival of parks in crowded or resource-

poor countries. For these reasons, the additional objectives

of local cooperation, education, and sustainable economic

development were soon added to initial biosphere reserve

goals of biological preservation and scientific research. At-

tention to humanitarian interests and economic development

concerns today sets apart the biosphere reserve network from

other types of nature preserves, which often garner resent-

ment from local populations who feel excluded and aban-

doned when national parks are established. United Nations

MAB guidelines encourage local participation in manage-

ment and development of biosphere reserves, as well as in

educational programs. Ideally, indigenous groups help ad-

minister reserve programs rather than being passive recipi-

ents of outside assistance or management.

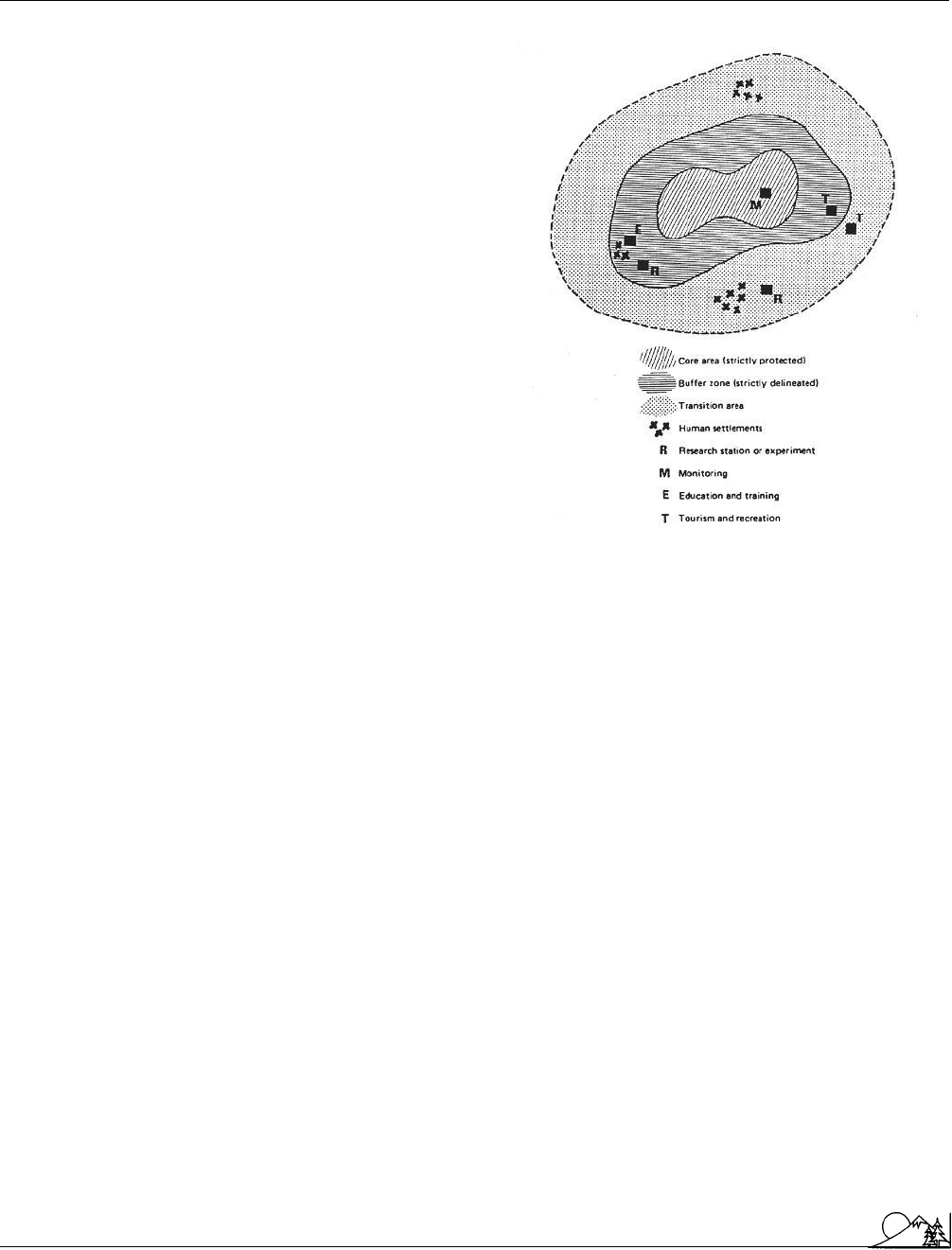

In an attempt to mesh the diverse objectives of bio-

sphere reserves, the MAB program has outlined a theoretical

reserve model consisting of three zones, or concentric rings,

with varying degrees of use. The innermost zone, the core,

should be natural or minimally disturbed, essentially without

human presence or activity. Ideally this is where the most

diverse plant and animal communities live and where natural

ecosystem

functions persist without human intrusion. Sur-

rounding the core is a

buffer

zone, mainly undisturbed but

containing research sites, monitoring stations, and habitat

rehabilitation

experiments. The outermost ring of the bio-

sphere reserve model is the transition zone. Here there may

be sparse settlement, areas of traditional use activities, and

tourist facilities.

Many biosphere reserves have been established in pre-

viously existing national parks or preserves. This is especially

common in large or wealthy countries where well established

park systems existed before the biosphere reserve idea was

conceived. In 1991 most of the United States’ 47 biosphere

reserves lay in national parks or wildlife sanctuaries. In coun-

tries with few such preserves, nomination for United Nations

biosphere reserve status can sometimes attract international

assistance and funding. In some instances debt for nature

swaps have aided biosphere reserve establishment. In such

an exchange, international

conservation

organizations pur-

chase part of a country’s national debt for a portion of its

face value, and in exchange that country agrees to preserve

an ecologically valuable region from destruction. Bolivia’s

Beni Biosphere Reserve came about this way in 1987 when

Conservation International

, a Washington-based organi-

zation, paid $100,000 to Citicorp, an international lending

institution. In exchange, Citicorp forgave $650,000 in Boliv-

ian debt, loans the bank seemed unlikely to ever recover,

and Bolivia agreed to set aside a valuable tropical mahogany

forest. This process has also produced other reserves, includ-

ing Costa Rica’s La Amistad, and Ecuador’s Yasuni and

Galapagos Biosphere Reserves.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Biosphere reserve

In practice, biosphere reserves function well only if

they have adequate funding and strong support from national

leaders, legislatures, and institutions. Without legal protec-

tion and long-term support from the government and its

institutions, reserves have no real defense against develop-

ment interests.

National parks can provide a convenient institutional

niche, defended by national laws and public policing agen-

cies, for biosphere reserves. Pre-existing wildlife preserves

and game sanctuaries likewise ensure legal and institutional

support. Infrastructure—management facilities, access

roads, research stations, and trained wardens—is usually al-

ready available when biosphere reserves are established in

or adjacent to ready-made preserves.

Funding is also more readily available when an estab-

lished

national park

or game preserve, with a pre-existing

operating budget, provides space for a biosphere reserve.

With intense competition from commercial loggers, miners,

and developers, money is essential for reserve survival. Espe-

cially in poorer countries, international experience increas-

ingly shows that unless there is a reliable budget for manage-

ment and education, nearby residents do not learn

cooperative reserve management, nor do they necessarily

support the reserve’s presence. Without funding for policing

and legal defense, development pressures can easily continue

to threaten biosphere reserves. Logging, clearing, and de-

struction often continue despite an international agreement

on paper that resource extraction should cease. Turning parks

into biosphere reserves may not always be a good idea. Na-

tional park administrators in some less wealthy countries fear

that biosphere reserve guidelines, with their compromising

objectives and strong humanitarian interests, may weaken

the mandate of national parks and wildlife sanctuaries set

aside to protect endangered species from population pres-

sures and development. In some cases, they argue, there

exists a legitimate need to exclude people if

rare species

such as

tigers

or

rhinoceroses

are to survive.

Because of the expense and institutional difficulties

of establishing and maintaining biosphere reserves, about

two-thirds of the world’s reserves exist in the wealthy and

highly developed nations of North America and Europe.

Poorer countries of Africa, Asia, and South America have

some of the most important remaining intact ecosystems,

but wealthy countries can more easily afford to allocate

the necessary space and money. Developed countries also

tend to have more established administrative and protective

structures for biosphere reserves and other sanctuaries. An

increasing number of developing countries are working to

establish biosphere reserves, though. A significant incentive,

aside from national pride in indigenous species, is the

international recognition given to countries with biosphere

reserves. Possession of these reserves grants smaller and

156

Schematic plan of a biosphere reserve. (Beacon

Press. Reproduced by permission.)

less wealthy countries some of the same status as that of

more powerful countries such as the United States, Ger-

many, and Russia.

Some difficult issues surround the biosphere reserve

movement. One question that arises is whether reserves

are chosen for reasons of biological importance or for

economic and political convenience. In many cases national

biosphere reserve committees overlook critical forests or

endangered habitats because logging and mining companies

retain strong influence over national policy makers. Another

problem is that in and around many reserves, residents

are not yet entirely convinced, with some reason, that

management goals mesh with local goals. In theory sustain-

able development methods and education will continue to

encourage communication, but cooperation can take a long

time to develop. Among reserve managers themselves, great

debate continues over just how much human interference is

appropriate, acceptable, or perhaps necessary in a place

ideally free of human activity. Despite these logistical and

theoretical problems, the idea behind biosphere reserves

seems a valid one, and the inclusiveness of biosphere

planning, both biological and social, is revolutionary.

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]