Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ment, labor regulation, and famine relief. They ar-

gued vehemently with the trade unions that there

should be special attention to female workers. They

published special “women’s pages” (stranichki

rabotnitsy) in the major newspapers, two popular

journals (Rabotnitsa and Krestyanka), and Kommu-

nistka, which was geared toward organizers and

instructors working among women.

With the introduction of the New Economic

Policy (NEP) in 1921, zhenotdel activists faced a

whole host of new problems: rising and dispro-

portionately female unemployment; cutbacks in

budgeting for local party committees which

prompted them to try to liquidate their women’s

sections altogether; cutbacks in the social services

(child care, communal kitchens, etc.) that zhenot-

del activists had hoped would assist in the eman-

cipation of women from the drudgery of private

child care and food preparation. Kollontai and her

colleagues now began insisting, in Kollontai’s

words, on not eliminating but strengthening the

women’s sections. They wanted the women’s sec-

tions to have more representatives on the factory

committees and Labor Exchanges (which handled

job placements for unemployed workers), in trade

unions, and in the Commissariats.

The party responded to this increased insistence

with charges of feminist deviation. In February

1922 Kollontai (now tainted as well by her in-

volvement in the Workers’ Opposition) was re-

placed as head of the zhenotdel by Sofia Smidovich.

Smidovich, a contemporary of Kollontai, was much

more socially conservative and less adamant about

all the injustices to women. Kollontai and her close

assistant, Vera Golubeva, did not cease to sound

the alarm about women’s plight, even when Kol-

lontai was reassigned to the Soviet trade union del-

egation in Norway. From her exile in 1922,

Kollontai, calling the New Economic Policy “the

new threat,” expressed fears that women would be

forced out of the workforce and back into domes-

tic subservience to their male companions. She now

even began to question whether feminism was such

a negative term.

The Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923 re-

acted vehemently against the possibility of any such

feminist deviations. At the same congress, Stalin

(normally reticent on women’s issues) now praised

women’s delegate meetings organized by the

zhenotdel as “an important, essential transmission

mechanism” between the party and the female

masses. As such, they should be used to “extend

and direct the party’s tentacles in order to under-

mine the influence of the priests among youth, who

are raised by women.” Through such tentacles, the

party would be able to “transmit its will to the

working class.” Three months later Smidovich an-

nounced that Kommunistka would no longer carry

theoretical discussions of women’s emancipation.

Unfortunately, the historical record of the

zhenotdel for the period after 1924 is less clear than

the earlier record because the relevant files of the

women’s section are missing from the party

archives. The women’s section in 1924–1925 was

headed by Nikolayeva, herself a woman of the

working class and long-time activist in the Lenin-

grad women’s section. In May 1924 the Thirteenth

Party Congress again attacked the zhenotdel, ac-

cusing it this time of one-sidedness (odnostoronnost)

for focusing too much on agitation and propaganda

rather than working directly on issues of women’s

daily lives. Soon thereafter Nikolayeva, Krupskaya,

and Lilina became embroiled in the Leningrad Op-

position. It is quite likely that the zhenotdel records

were purged because of this.

Alexandra Artyukhina, newly appointed as di-

rector of the section (replacing Nikolayeva), made

a point of arguing that the women’s sections

should propagandize against the Leningrad Oppo-

sition on the grounds that otherwise female work-

ers would fall for their false slogans in favor of

“equality” and “participation in profits.” Now more

than ever the women’s sections strove to prove

their original contention that they had “no tasks

separate from the tasks of the party.” During the

second half of the 1920s the women’s section toed

the party line, participating in military prepared-

ness exercises for women workers during the war

scare of 1927, as well as in the collectivization and

industrialization drives of 1928–1930.

In January 1930 the Central Committee of the

CPSU announced that the women’s sections were

being liquidated as part of a general reorganization

of the party. While the decree declared that work

among the female masses had “the highest possi-

ble significance,” this work was now to be done by

all the sections of the Central Committee rather

than by special women’s sections. In some parts of

the country, especially Central Asia, the women’s

sections were replaced by women’s sectors

(zhensektory). Kommunistka was completely closed

down. Lazar Kaganovich, Stalin’s spokesman for

this move, claimed that since the women’s section

had now completed the circle of its development, it

was no longer necessary. The historic “woman

question” had now been solved.

ZHENOTDEL

1727

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The impossible position of the women’s sec-

tions can be clearly seen in resolutions and criti-

cisms of the last years of their existence. They were

sometimes criticized for devoting too little atten-

tion to daily life (byt), while other times they were

attacked for too much of a social welfare bias in

helping women in their daily lives. If they were too

outspoken, they were accused of feminist devia-

tions, while if they were not visible enough in their

work, they were accused of passivity. Ultimately,

the untenable position of the women’s sections

arose from their position as transmission belts be-

tween the party and the masses. While the founders

of the zhenotdel had hoped that they could carry

women’s voices and needs to the party, the party

insisted that the principal role of the women’s sec-

tions was to convey the party’s will to the female

masses.

See also: ABORTION POLICY; ARMAND, INESSA; FEMINISM;

KOLLONTAI, ALEXANDRA MIKHAILOVNA; KRUPSKAYA,

NADEZHDA KONSTANTINOVNA; MARRIAGE AND FAM-

ILY LIFE; SAMOILOVA, KONDORDIYA NIKOLAYEVNA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clements, Barbara Evans. (1992). “The Utopianism of the

Zhenotdel.” Slavic Review 51:485–496.

Clements, Barbara Evans. (1997). Bolshevik Women. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Elwood, Ralph C. (1992). Inessa Armand: Revolutionary

and Feminist. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Goldman, Wendy Z. (1996). “Industrial Politics, Peasant

Rebellion, and the Death of the Proletarian Women’s

Movement in the USSR.” Slavic Review 55:46–77.

Hayden, Carol Eubanks. (1976). “The Zhenotdel and the

Bolshevik Party.” Russian History 3(2):150–173.

Massell, Gregory. (1974). The Surrogate Proletariat: Moslem

Women and Revolutionary Strategies in Soviet Central

Asia, 1919–1929. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univer-

sity Press.

Wood, Elizabeth A. (1997). The Baba and the Comrade:

Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

E

LIZABETH

A. W

OOD

ZHENSOVETY

The zhenskie sovety (women’s councils), or zhensovety

in shortened form, were set up after 1958 under

Nikita Khrushchev as part of his attempt to mobi-

lize the Soviet people around issues concerning their

lives. Involvement in trades unions, comrades

courts, and citizens’ volunteer detachments was

also encouraged during this period. The zhensovety

were part of Khrushchev’s “differentiated ap-

proach” to politics, according to which women’s

organizations were now acceptable again on the

grounds that they targeted one particular group of

citizens, just as other organizations dealt with par-

ticular groupings, such as youth and pensioners.

From 1930 when Stalin declared the “woman ques-

tion” to be solved, separate organizations for

women, with the exception of the movement of

wives (dvizhenie zhen), were closed down on the

grounds that they smacked of “bourgeois femi-

nism” and were divisive of working-class unity.

Now it was recognized that the political education

of women was one of the weakest areas of party

work and in need of attention.

Zhensovety were formed in factories and of-

fices and on farms. They were set up at regional

(oblast), territory (kray), and district (rayon) levels

of administration. Their sizes varied from around

thirty to fifty members at regional levels and fif-

teen to twenty at district level to smaller groups of

five to seventeen in factories and farms. There was

no uniform pattern across the women’s councils,

as some were closely affiliated with the party, oth-

ers with the soviets, and still others with the trade

union. They divided their work into sections such

as daily life, culture, mass political work, child care,

health care, and sanitation and hygiene. Their ac-

tivities usually reflected official party priorities for

work among women.

The zhensovety continued to exist on paper in

the years of Leonid Brezhnev’s leadership but in fact

did very little. They were formal in most areas

rather than active. As part of his policy of democ-

ratization, Mikhail Gorbachev revived and restruc-

tured them. In 1986, at the Twenty-Seventh Party

Congress in Moscow, Gorbachev called for their

reinvigoration. By the spring of 1988, 2.3 million

women were active in 236,000 zhensovety. As in

the past, each women’s council was preoccupied with

issues of local concern. Their work was divided into

the typical sections of “daily life and social prob-

lems,” “production,” “children,” and “culture.”

At the nineteenth All-Union Conference of the

CPSU in June 1988, Gorbachev argued that

women’s voices were not heard and that this had

been the case for years. He regretted that the

women’s movement was at a “standstill,” at best

“formal.” He placed the zhensovety for the first

ZHENSOVETY

1728

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

time under the hierarchical umbrella of the Soviet

Women’s Committee. In 1989 Gorbachev reformed

the electoral system. In the newly elected Congress

of People’s Deputies, the zhensovety had 75 “saved”

seats among the 750 seats reserved for social or-

ganizations.

See also: FEMINISM; MARRIAGE AND FAMILY LIFE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Browning, Genia. (1987). Women and Politics in the USSR.

New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Browning, Genia. (1992). “The Zhensovety Revisited.” In

Perestroika and Soviet Women, ed. Mary Buckley.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Buckley, Mary. (1989). Women and Ideology in the Soviet

Union. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Buckley, Mary. (1996). “The Untold Story of Obshch-

estvennitsa in the 1930s.” Europe-Asia Studies

48(4):569–586.

Friedgut, Theodore H. (1979). Political Participation in the

USSR. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

M

ARY

B

UCKLEY

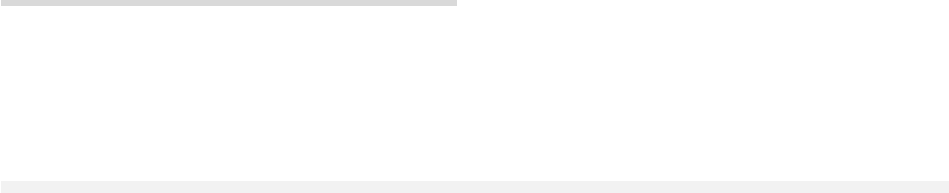

ZHIRINOVSKY, VLADIMIR VOLFOVICH

(b. 1946), founder and leader of the Liberal-

Democratic Party of Russia, deputy speaker of the

State Duma.

Born in Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan, Vladimir

Volfovich Zhirinovsky was the son of a Jewish

lawyer from Lviv and a Russian woman. After his

father’s death he was raised by his mother. He

graduated from Moscow State University in 1969,

then served in the army in Tiflis, where he worked

in military intelligence. From 1973 to 1991 Zhiri-

novsky worked at various jobs in Moscow and at

night attended law school at Moscow State Uni-

versity. In the 1980s he directed legal services for

Mir publishing.

With the coming of perestroika Zhirinovsky

began his political career. In 1988 he founded the

Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR), the sec-

ond legal party registered in the Soviet Union. In

1991 he ran for the presidency of Russia and re-

ceived 6 million votes. Emphasizing populism and

great-power chauvinism and denouncing corrup-

tion, he built up a loyal party organization. In

the December 1993 parliamentary elections, Zhiri-

novsky parlayed discontent with Boris Yeltsin into

a plurality in the State Duma. In the complex elec-

tion system for individual candidates and party

slates, the LDPR received 23 percent of the total

vote, fifty-nine of the party seats in the Duma, and

five individual seats.

In the December 1995 Duma elections, the

LDPR vote fell sharply to 11.1 percent, and the

party won only fifty-five seats in the parliament,

well behind the resurgent Communist Party. In

1996 Zhirinovsky ran for president again, but this

time he finished fifth (5.7 percent) in the first round

of voting and was eliminated.

In the Duma elections of 1999 the LDPR drew

6.4 percent of the vote and got nineteen seats. Zhiri-

novsky was elected deputy speaker of the Duma.

In the 2000 presidential election he ran again and

drew only 2.7 percent of the vote, or a little more

than 2 million out of the 75 million who voted.

Zhirinovsky supported both the first and the sec-

ond Chechen War. An acute student of mass me-

dia, he remained in the national spotlight by

combining outlandish behavior, populist appeal,

and authoritarian nationalism. His antics included

fist fights on the floor of the Duma and throwing

ZHIRINOVSKY, VLADIMIR VOLFOVICH

1729

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Ultra-nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky rails against the United

States during a January 19, 2003, rally in Moscow. © AFP/

CORBIS

orange juice on Boris Nemtsov during a television

debate. He made headlines by threatening to take

Alaska back from the United States and to flood

the Baltic republics with radioactive waste. Zhiri-

novsky has called for a Russian dash to the south

that would end “when Russian soldiers can wash

their boots in the warm waters of the Indian

Ocean.”

See also: LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fraser, Graham, and Lancelle, George. (1994). Absolute

Zhirinovsky: A Transparent View of the Distinguished

Russian Statesman. New York: Penguin Books.

Kartsev, Vladimir, with Todd Bludeau. (1995). Zhiri-

novsky! New York: Columbia University Press.

Kipp, Jacob W. (1994).“The Zhirinovsky Threat.” For-

eign Affairs 73(3):72-86.

Zhirinovsky, Vladimir. (1996). My Struggle: The Explo-

sive Views of Russia’s Most Controversial Public Figure.

New York: Barricade Books.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

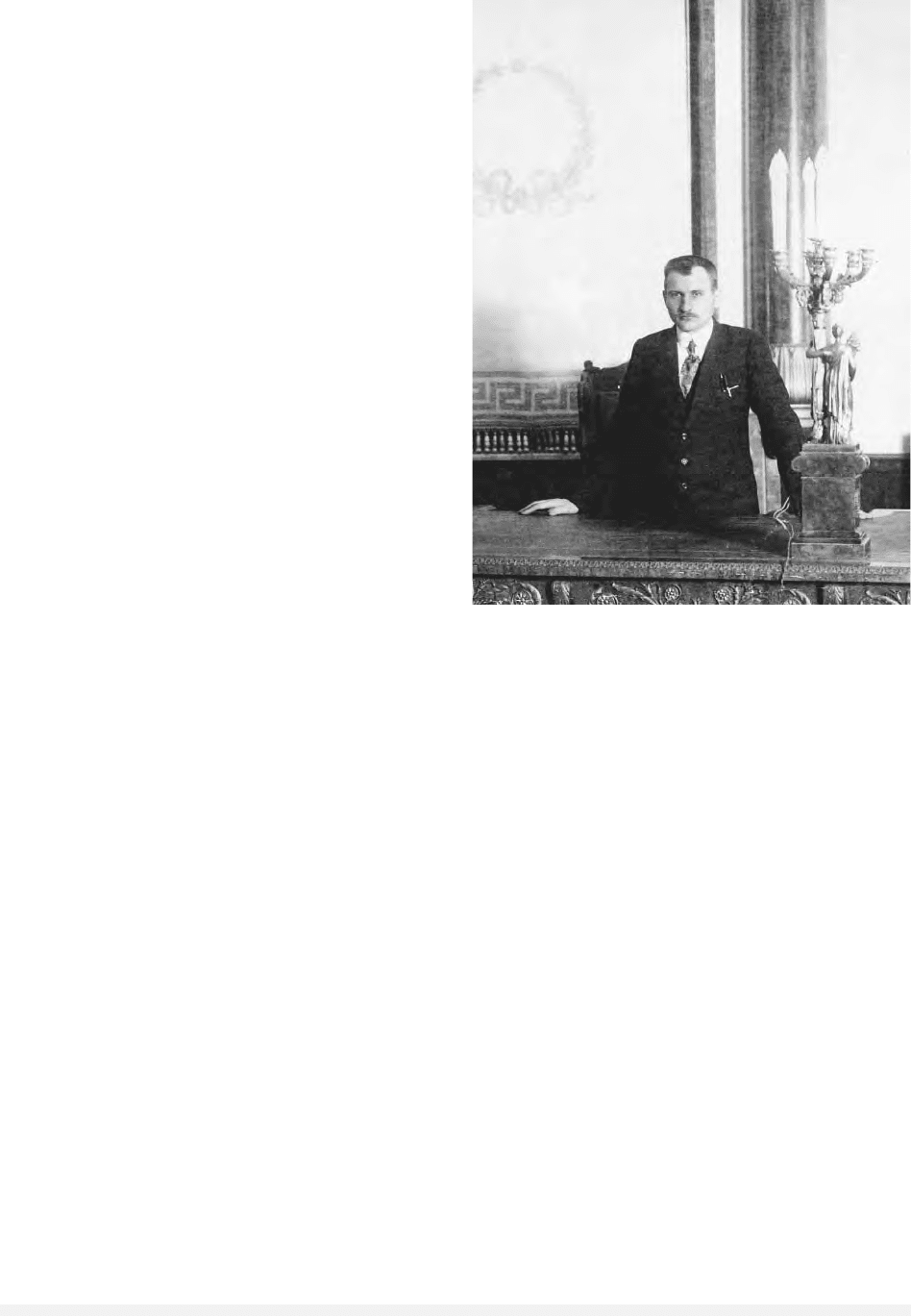

ZHORDANIA, NOE NIKOLAYEVICH

(1868–1953), Menshevik leader; president of Geor-

gia.

The most important leader of the Georgian So-

cial Democrats (Mensheviks), Noe Nikolayevich

Zhordania was born in western Georgia to a petty

noble family. Educated at the Tiflis Orthodox Sem-

inary (just years before Josef Stalin entered that

institute that bred so many revolutionaries), Zhor-

dania went on to Warsaw for further education

and there was introduced to Marxism. His writings

in the Georgian progressive journal kvali (trace) in

the early 1890s inspired young radicals soon to be

known as the mesame dasi (third generation). Zhor-

dania combined a Marxist critique of Russian au-

tocracy and the Armenian-dominated capitalism of

his native Georgia with a patriotism that appealed

broadly to workers, students, and peasants. By

1905 he had affiliated with the more moderate

wing of Russian Social Democracy, the Menshe-

viks, and took the bulk of Georgian Social Demo-

crats along with him. Radicals like the young Stalin

were isolated in the Georgian party and eventually

made their careers outside the country.

During the first Russian Revolution in 1905–

1906, the Mensheviks dominated Georgia, essen-

tially routing tsarist authority in the country, but

brutal repression restored the rule of the govern-

ment. In 1906 Zhordania was elected to the first

State Duma, the new parliament conceded by the

tsar. But within a few months the tsar dissolved

the duma, and Zhordania and other radicals signed

the Vyborg Manifesto protesting the dissolution.

Zhordania was forced into the political under-

ground, writing for clandestine newspapers and

sparring in print with Stalin over the question of

non-Russian nationalities.

With the outbreak of the revolution in 1917

Zhordania became the chairman of the Tiflis So-

viet. He was an opponent of the Bolshevik victory

in Petrograd in October of that year and was in-

strumental in the declaration of an independent

Georgian republic on May 26, 1918. Zhordania

was elected president of the republic and served un-

til the invasion of the Red Army in February 1921.

From exile in France he planned an insurrection

against the Communist government, but the revolt

of August 1924 was bloodily suppressed by the So-

viets. Zhordania spent his last years in exile, largely

in France, writing his memoirs, conspiring with

Western intelligence agencies against the Soviets in

Georgia, still the acknowledged leader of a movement

whose members fought bitterly one with another.

See also: CAUCAUS; GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS; MENSHE-

VIKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jones, Stephen. (1989). “Marxism and Peasant Revolt in

the Russian Empire: The Case of the Gurian Re-

public.” Slavonic and East European Review 67(3):

403–434.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. (1994). The Making of the Georgian

Nation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

R

ONALD

G

RIGOR

S

UNY

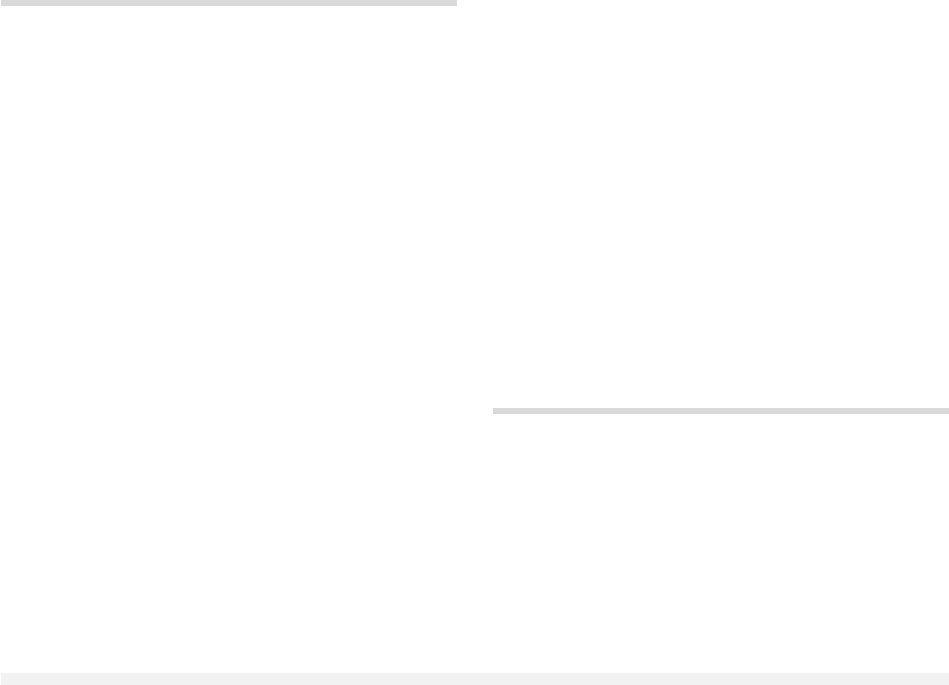

ZHUKOV, GEORGY KONSTANTINOVICH

(1896–1974), marshal of the Soviet Union (1943),

four-time Hero of the Soviet Union, and the Red

Army’s “Greatest Captain” during the Soviet

Union’s Great Patriotic War (World War II).

Stalin’s closest wartime military confidant,

Georgy Zhukov was a superb strategist and prac-

ZHORDANIA, NOE NIKOLAYEVICH

1730

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

titioner of operational art who nonetheless dis-

played frequent tactical blemishes. Unsparing of

himself, his subordinates, and his men, he was

renowned for his iron will, strong stomach, and

defensive and offensive tenacity.

A veteran of World War I and the Russian Civil

War, Zhukov graduated from the Senior Com-

mand Cadre Course in 1930 and became deputy

commander of the Belorussian Military District in

1938 and commander of Soviet Forces in Mongo-

lia in 1939. After Zhukov defeated Japanese forces

at Khalkhin Gol in August 1939, Stalin appointed

him commander of the Kiev Special Military Dis-

trict in June 1940 and Red Army Chief of Staff

and Deputy Peoples’ Commissar of Defense in Jan-

uary 1941.

During World War II, Zhukov served on the

Stavka VGK (Headquarters of the Supreme High

Command) as First Deputy Peoples’ Commissar of

Defense and Deputy Supreme High Commander, as

Stavka VGK representative to Red Army forces, and

as front commander. In June 1941 Zhukov or-

chestrated the Southwestern Front’s unsuccessful

armored counterstrokes near Brody and Dubno

against German forces in Ukraine. As Reserve Front

(army group) commander from July to Septem-

ber, Zhukov slowed the German advance at

Smolensk, prompting Hitler to delay his offensive

against Moscow temporarily. Zhukov directed the

Leningrad Front’s successful defense of Leningrad

in September 1941 and the Western Front’s suc-

cessful defense and counteroffensive at Moscow in

the winter of 1941–1942.

In the summer of 1942, Zhukov’s Western

Front conducted multiple offensives to weaken

the German advance toward Stalingrad and, in

November-December 1942, led Operation Mars,

the failed companion piece to the Red Army’s

Stalingrad counteroffensive (Operation Uranus),

against German forces west of Moscow. During

the winter campaign of 1942–1943, Zhukov co-

ordinated Red Army forces in Operation Spark,

which partially lifted the Leningrad blockade, and

Operation Polar Star, an abortive attempt to defeat

German Army Group North and liberate the en-

tire Leningrad region. While serving as Stavka

VGK representative throughout 1943 and 1944,

Zhukov played a decisive role in Red Army victo-

ries at Kursk and Belorussia, the advance to the

Dnieper, and the liberation of Ukraine, while suf-

fering setbacks in the North Caucasus (April-May

1943) and near Kiev (October 1943). Zhukov com-

manded the First Belorussian Front in the libera-

tion of Poland and the victorious but costly Battle

of Berlin.

After commanding the Group of Soviet Occu-

pation Forces, Germany, and the Soviet Army

Ground Forces, and serving briefly as Deputy

Armed Forces Minister, Zhukov was “exiled” in

1946 by Stalin, who assigned him to command the

Odessa and Ural Military Districts, ostensibly to re-

move a potential opponent. Rehabilitated after

Stalin’s death in 1953, Zhukov served as minister

of Defense and helped Khrushchev consolidate his

political power in 1957. When Zhukov resisted

Khrushchev’s policy for reducing Army strength,

at Khrushchev’s instigation, the party denounced

Zhukov, ostensibly for “violating Leninist princi-

ples” and fostering a “cult of Comrade G.K.

Zhukov” in the army. Replaced as minister of De-

fense by Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky in Octo-

ber 1957 and retired in March 1958, Zhukov’s

reputation soared once again after Khrushchev’s re-

moval as Soviet leader in 1964.

ZHUKOV, GEORGY KONSTANTINOVICH

1731

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Marshal Georgy Zhukov led the Red Army to victory in World

War II and helped bring Nikita Khrushchev to power in 1953.

© H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

See also: KHRUSHCHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; STALIN,

JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anfilov, Viktor. (1993). “Georgy Konstantinovich Zhu-

kov.” In Stalin’s Generals, ed. Harold Shukman. Lon-

don: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Glantz, David M. (1999). Zhukov’s Greatest Defeat: The

Red Army’s Epic Disaster in Operation Mars, 1942.

Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Zhukov, Georgy Konstantinovich. (1985). Reminiscences

and Reflections. 2 vols. Moscow: Progress.

D

AVID

G

LANTZ

ZHUKOVSKY, NIKOLAI YEGOROVICH

(1847–1921), scientist whose research typified the

innovative avionics of prerevolutionary Russia.

Like a number of other outstanding Russian

scientists of the early Soviet period, Nikolai

Yegorovich Zhukovsky was trained in the tsarist

era and began his scientific career before the revo-

lution. A specialist in aerodynamics and hydrody-

namics, he supervised the construction of one of

the world’s first experimental wind tunnels in 1902

and founded the first European institute of aero-

dynamics in 1904. He was a corresponding mem-

ber of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Early

in the Soviet period, Zhukovsky was chosen to head

the new Central Aero-Hydrodynamics Institute.

Zhukovsky developed the principal concepts

underlying the science of space flight, and in that

sense he was a pioneer, not only of aviation in pre-

revolutionary Russia, but of the later strides made

by Soviet scientists. One of his innovations was the

testing of intricate aerial maneuvers (e.g., loop-the-

loop, barrel rolls, spins) based on his earlier stud-

ies of the flight of birds. Vladimir I. Lenin called

Zhukovsky the “father of Russian aviation.” He

died of old age at seventy-four.

See also: AVIATION; SPACE PROGRAM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Oberg, James E. (1981). Red Star in Orbit. New York:

Random House.

Petrovich, G. V., ed. (1969). The Soviet Encyclopedia of

Space Flight. Moscow: Mir.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

ZINOVIEV, GRIGORY YEVSEYEVICH

(1883–1936), Bolshevik revolutionary leader and

associate of Lenin who after 1917 became first an

ally, then rival, of Stalin and later fell victim to the

Great Purge.

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev was born as

Yevsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky in Yeliza-

vetgrad (later renamed Zinoviesk, now Kirovohrad,

Kherson province, Ukraine). Of lower-middle-class

Jewish origin, and with no formal education, he

joined the Russian Social Democratic Workers’

Party in 1901. When the party split in 1903, Zi-

noviev followed Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik faction.

Having gained experience as a political agitator in

St. Petersburg during the 1905 Revolution, he be-

came a member of the party’s Central Committee

in 1907. After a brief term in prison the following

year, Zinoviev was released because of his poor

health and joined Lenin in western European exile.

A fiery orator and provocative political writer, dur-

ing the next ten years Zinoviev edited numerous

Bolshevik publications and supported Lenin against

opposition from both within the party and other

revolutionary groups. In April 1917, after the over-

throw of the tsar at the end of February, Zinoviev

returned with Lenin to Russia on the “sealed” train

through Germany and took over editorship of the

Bolshevik newspaper Pravda until it was banned in

July. During the year, however, Zinoviev increas-

ingly took issue with Lenin’s confidence in Bolshe-

vik strength and his refusal to collaborate with

other socialist groups. In October, Zinoviev to-

gether with Lev Kamenev opposed the Bolshevik

leader’s plans for an armed seizure of power. When

Lenin the following month refused to include rep-

resentatives of other socialist parties in the new So-

viet government, Zinoviev (with four others)

resigned from the Bolshevik Central Committee in

protest. He was readmitted only a few days later

after publication of his “Letter to the Comrades” in

Pravda, in which he submitted to Party discipline.

In January 1918, Zinoviev became head of the Pet-

rograd Revolutionary Committee. In March 1919

he was elected chairman of the Executive Commit-

tee of the newly founded Communist International

(Comintern). By 1921, he was a full member of the

Politburo, chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, and

leader of the regional Party organization. After

Lenin’s death in January 1924, Zinoviev and

Kamenev joined with Josef Vissarionovich Stalin in

a tactical “triumvirate” to counter the aspirations

of Leon Trotsky to the Party leadership. After Trot-

ZHUKOVSKY, NIKOLAI YEGOROVICH

1732

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

sky’s defeat in 1925, Stalin turned against his for-

mer allies, who strove to maintain their authority

by realigning themselves with Trotsky in the

United Opposition against Stalin. Politically out-

maneuvered, Zinoviev lost control of the Leningrad

party organization and the Comintern in 1926 and

in November the following year was expelled from

the Communist Party. By publicly recanting his

opposition to Stalin on several occasions, Zinoviev

strove in vain to rehabilitate himself. In January

1935 he was arrested on charges of “moral com-

plicity” in the assassination of Leningrad Party

leader Sergei Mironovich Kirov, tried in secret, and

sentenced to ten years in prison. In August 1936,

Zinoviev was brought before the public in the first

Moscow show trial. Abjectly accepting all the

charges of terrorism and treason levelled against

him, Zinoviev was condemned to death and exe-

cuted on August 25, 1936. He was rehabilitated by

the Soviet government in 1988.

See also: COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL; LENIN, VLADIMIR

ILICH; SHOW TRIALS; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH;

UNITED OPPOSITION; ZINOVIEV LETTER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Haupt, Georges, and Marie, Jean-Jacques, eds. (1974).

Makers of the Russian Revolution. London: Allen and

Unwin.

Hedlin, Myron W. (1975). “Zinoviev’s Revolutionary

Tactics in 1917.” Slavic Review 34(1):19–43.

N

ICK

B

ARON

ZINOVIEV LETTER

Letter of mysterious provenance purporting to

have been sent by Grigory Zinoviev, head of the

Communist International (Comintern), to the British

Communist Party with instructions to prepare for

revolution.

The letter was first published on October 25,

1924, four days before a general election, in the

British newspaper Daily Mail under the headline

“Civil War Plot by Socialists’ Masters.” Its appear-

ance caused great embarrassment to the Labour

government of Ramsey MacDonald, which on Feb-

ruary 2 of that year had bestowed diplomatic

recognition on the Soviet Union and on August 10

had concluded a series of trade treaties, now await-

ing parliamentary ratification. A conservative vic-

tory in the October 29 elections signaled instead the

launch of a vigorously anti-Soviet line, culminat-

ing in the abrogation of diplomatic ties in May

1927. Denounced immediately by the Soviet gov-

ernment as a forgery, investigations at the time and

since have failed to discover conclusive proof of the

letter’s authorship, which has been variously at-

tributed to White Russian émigrés, Polish spies, the

British secret services, communist provocateurs, or

possibly even to Zinoviev. In January 1999, the

British government published a report on the let-

ter based on research in British and Russian secret

service archives. This proposed that the document

was a forgery instigated by White Russian agents

in Berlin, carried out in Riga, Latvia, drawing on

genuine intelligence information concerning Com-

intern activities, and channeled by British intelli-

gence to Britain, where certain right-wing members

of the security service proved eager to vouch for

its authenticity and ensure it reached the press. The

letter and subsequent “Red scare” did not, however,

cause Labour’s electoral defeat or discredit the

party, which had already suffered a parliamentary

vote of no confidence and loss of Liberal support.

Indeed, the Labour party’s vote in 1924 grew by

one million over the previous year’s election.

See also: GREAT BRITAIN, RELATIONS WITH; ZINOVIEV,

GRIGORY YEVSEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andrew, Christopher. (1977). “The British Secret Service

and Anglo-Soviet Relations in the 1920s, Part 1:

From the Trade Negotiations to the Zinoviev Letter.”

The Historical Journal 20:673–706.

Bennett, Gill. (1999). “A Most Extraordinary and Mys-

terious Business.” In The Zinoviev Letter of 1924. Lon-

don: Foreign & Commonwealth Office, General

Services Command.

Chester, Lewis; Fay, Stephen; and Young, Hugo. (1967).

The Zinoviev Letter. London: Heinemann.

N

ICK

B

ARON

ZUBATOV, SERGEI VASILIEVICH

(1864–1917), senior security police official.

Born and raised in Moscow, the son of a mil-

itary officer, Sergei Zubatov was a staunch defender

of the Russian monarchy who reorganized the

Russian security police and created progovernment

ZUBATOV, SERGEI VASILIEVICH

1733

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

labor organizations. These activities earned him

fear and anger from the revolutionary activists

with whom he matched wits, as well as from more

conservative government officials.

Zubatov had exceptional rhetorical talents and

a magnetic personality. He was the best-read stu-

dent in his high school and the leader of a discus-

sion circle. Although he associated with radical

intellectuals, he advocated reform and opposed rev-

olution. A self-proclaimed follower of Dmitry Pis-

arev, he believed that education and cultural

development offered the best path to social im-

provement. He left high school before graduation,

in 1882 or 1883, worked in the Moscow post of-

fice, and married the proprietress of a private self-

education library that stocked forbidden books. Yet

he developed monarchist views and became a po-

lice informant in 1885. He openly joined the secu-

rity police in 1889 after radical activists discovered

his dual role.

As director of the Moscow security bureau

from 1896, Zubatov led the antirevolutionary

fight. Activists who fell into his snares found a

well-read official who argued passionately that

only revolutionary violence was preventing the ab-

solutist monarchy from implementing reforms.

Using charm and eloquence, he recruited talented,

and sometimes dedicated, secret informants who

laid bare the revolutionary underground. He sys-

tematized the use of plainclothes detectives, created

a mobile surveillance brigade staffed with two

dozen such detectives, and trained gendarme offi-

cers from around the empire. The major revolu-

tionary organizations found it hard to withstand

Zubatov’s sophisticated assault.

Zubatov himself was not a gendarme officer,

but a civil servant who attained only the seventh

rank (nadvornyi sovetnik), or lieutenant colonel in

military terms. Had he risen through the hierar-

chical, regimented military, he probably would not

have conceived of “police socialism.” This policy ad-

vocated not the redistribution of wealth but the

backing of workers in economic disputes with em-

ployers. In 1901, with the patronage of senior

Moscow officials, he organized societies that pro-

vided cultural, legal, and material services to fac-

tory workers. Within a year, analogous societies

sprang up in other cities, including Minsk, Kiev,

and Odessa.

In the fall of 1902 Zubatov was invited to re-

organize the nerve center of the Russian security

police. As chief of the Special Section of the Police

Department in St. Petersburg, he created a network

of security bureaus in twenty cities from Vilnius

to Irkutsk. He staffed many of them with his pro-

teges trained in the new methods of security polic-

ing and encouraged to deploy secret informants

within the revolutionary milieu.

Meanwhile, however, his worker societies

slipped out of control. In July 1903 a general strike

broke out in Odessa and labor unrest swept across

the south. Zubatov advocated restraint, but the

Minister of Interior, Vyacheslav Plehve, used troops

to restore order. Disillusioned with Zubatov’s la-

bor policies and suspecting him of personal disloy-

alty, Plehve banished him from the major cities of

the empire. Zubatov refused invitations to return

to police service after Plehve’s assassination in

1904. A monarchist to the last, he fatally shot him-

self following the emperor’s abdication in 1917.

See also: PLEHVE, VYACHESLOV KONSTANTINOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Daly, Jonathan W. (1998). Autocracy under Siege: Secu-

rity Police and Opposition in Russia, 1866–1905.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Ruud, Charles A., and Stepanov, Sergei. (1999). Fontanka

16: The Tsar’s Secret Police. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s

University Press.

Schneiderman, Jeremiah. (1976). Sergei Zubatov and Rev-

olutionary Marxism: The Struggle for the Working Class

in Tsarist Russia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Zuckerman, Frederick S. (1996). The Tsarist Secret Police

in Russian Society, 1880–1917. New York: New York

University Press.

J

ONATHAN

W. D

ALY

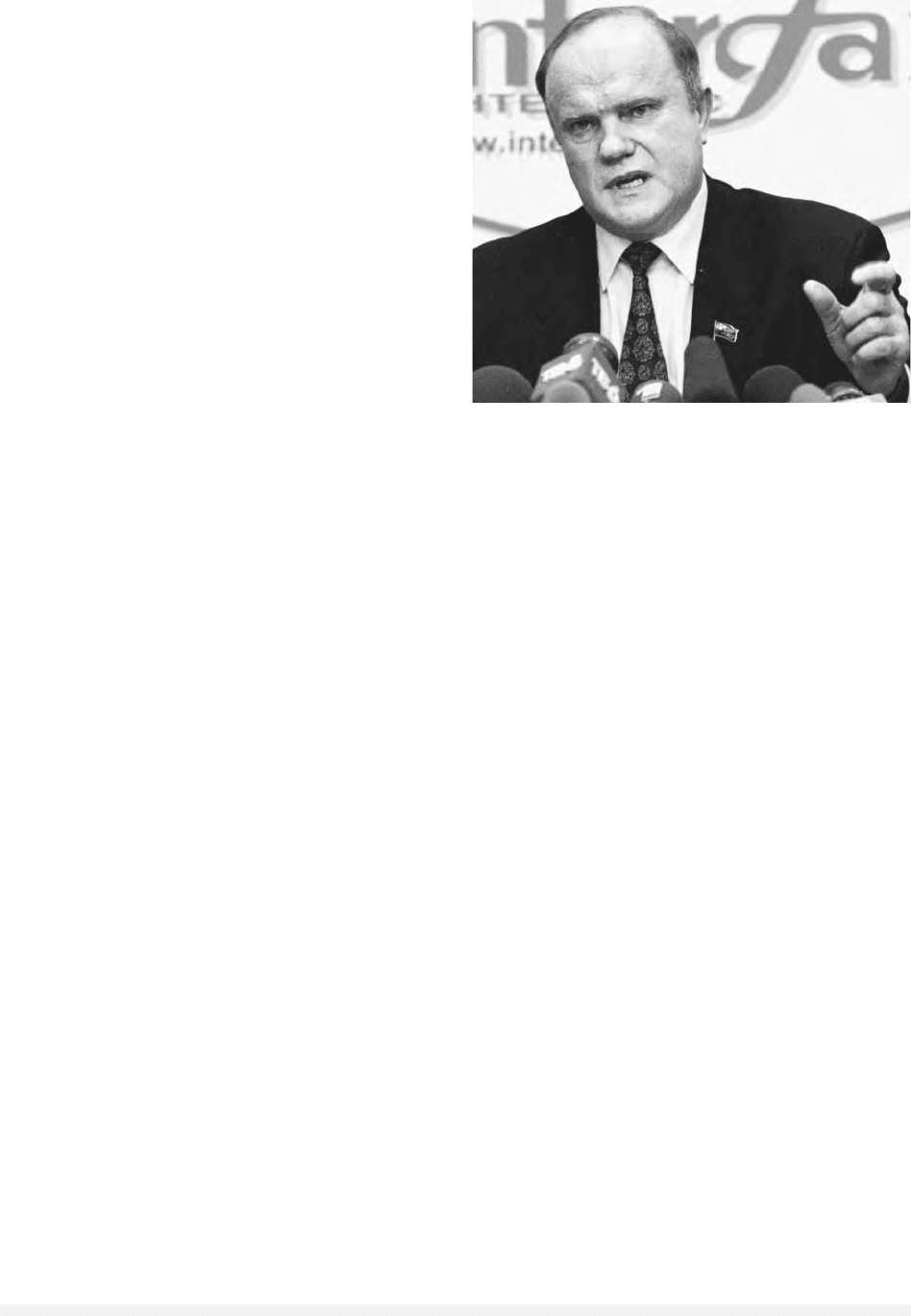

ZYUGANOV, GENNADY ANDREYEVICH

(b. 1944), Russian politician, chair of the Commu-

nist Party of the Russian Federation and head of its

parliamentary faction since 1993.

Gennady Andreyevich Zyuganov was born on

June 26, 1944, in Mymrino, Russia. A member

of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s

(CPSU) ideological department from 1983, Gen-

nady Zyuganov sympathized with the conserva-

tive opposition to Gorbachev and helped found the

anti-reform Russian Communist Party within the

ZYUGANOV, GENNADY ANDREYEVICH

1734

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

CPSU in 1990. He first gained notoriety as an anti-

Gorbachev polemicist on the eve of the August

1991 coup and as a defender of the Russian Com-

munist Party when Yeltsin banned it (from August

1991 to November 1992).

As a prolific opposition publicist from the early

1990s, Zyuganov’s achievement was the rehabili-

tation of communism as a serious intellectual and

political force. Ideologically, however, his “conser-

vative communism” came to owe less of a debt to

its Marxist-Leninist forebears and instead drew

heavily from the idea of a Soviet “national Bolshe-

vism,” which justified communist rule more for its

service to national greatness than for its promise

of a classless future. Zyuganov argued that Marx-

ism was only one of the methods necessary for

analyzing modern society, in which defense of

Russian cultural and historical traditions, preser-

vation of a global zone of influence, and the forg-

ing of broad alliances with national capitalists

against the West took precedence over class revo-

lution within Russia itself.

Zyuganov realized that the communists ur-

gently needed new ideas and allies merely to sur-

vive during and after the ban on their party, and

that following the collapse of the USSR they could

ignore issues of personal, ethnic, and national se-

curity only at their peril. More perceptively, he

judged that Russia’s post-1991 intellectual com-

mitment to market liberalism was deeply equivo-

cal and offered in its stead a kind of “state

patriotism,” based on the idea that communists and

non-communists alike could unite in defending

Russia’s state as the cradle of their common cul-

tural heritage. This, he believed was a unifying vi-

sion that could fill the “ideological vacuum” left

by Marxism-Leninism. Indeed, Zyuganov sought

to reverse the liberal consensus that the period

from 1917 to 1991 was a “Soviet experiment.” To

achieve this, he argued that liberalism itself was

the imposition alien to the collectivist and spiritual

traditions that had been best expressed under com-

munism. Simultaneously, Zyuganov was an ener-

getic and practical politician; his alliance-building

with nationalist and other opposition politicians

helped him to become Communist Party leader in

February 1993 and to formulate a consistent

theme. He based his presidential bids on broad “na-

tional-patriotic fronts” that sought to extend the

communists’ appeal.

Zyuganov has presented a complex figure,

whose leadership, ideas, and personality have been

much critiqued. The prevalent Western view of him

as a plodding party bureaucrat is a caricature, high-

lighting his lack of charisma while underestimat-

ing his tactical and organizational skill. The view

of Zyuganov as a fascistic nationalist, most tren-

chantly argued by academic Veljko Vujacic, iden-

tifies his dalliance with Stalinism and anti-Semitism,

while underplaying his moderate conservatism.

Marxist charges that he renounced socialism and

radicalism entirely correctly identify his debts to

conservative Russian nationalism, while underesti-

mating the necessity he faced of making ideologi-

cal and electoral compromises. Even judged by his

own aims, Zyuganov remains a paradoxical figure.

His leftist critics have alleged that he failed to move

Russia “forward to socialism” by failing to provide

an intellectually coherent socialist alternative.

While his arguments have found increasing appeal,

particularly in governing circles, and his party was

the most popular in parliamentary elections in the

1990s, he lost to Yeltsin in the 1996 presidential

election run-off, and Vladimir Putin beat him by

over twenty percent in the first round of the pres-

idential election in March 2000.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERA-

TION; PUTIN, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH; YELTSIN,

BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

ZYUGANOV, GENNADY ANDREYEVICH

1735

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Gennady Zyuganov, chair of the Communist Party of the

Russian Federation, was Boris Yeltsin’s foe in parliament and

for the presidency.

P

HOTOGRAPH BY

M

ISHA

J

APARIDZE

. AP/WIDE

WORLD PHOTOS. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lester, Jeremy. (1995). Modern Tsars and Princes: The

Struggle for Hegemony in Russia. London; New York:

Verso.

March, Luke. (2002). The Communist Party in Post-Soviet

Russia. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Vujacic, Veljko. (1996). “Gennadiy Zyuganov and the

‘Third Road’.” Post-Soviet Affairs 12: 118–154.

Zyuganov, Gennady A. (1997). My Russia: The Political

Autobiography of Gennady Zyuganov. Armonk, NY:

M.E. Sharpe.

L

UKE

M

ARCH

ZYUGANOV, GENNADY ANDREYEVICH

1736

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY