Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In 1303 Yuri succeeded his father Daniel

Yaroslavich to Moscow. After Grand Prince Andrei

Alexandrovich of Vladimir died in 1304, Yuri chal-

lenged Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver for the grand

princely throne. He visited Khan Tokhta in Saray,

intending to buy the patent for Vladimir with

gifts, but Mikhail won. Because Yuri rejected the

decision, Mikhail attacked Moscow unsuccessfully

in 1305 and 1308. His son Dmitry also marched

against Yuri, but Metropolitan Peter, who sup-

ported Moscow, stopped him. The Novgorodians

also preferred Yuri and invited him in 1314 to be

their prince. Mikhail, however, repossessed the

town in Yuri’s absence in 1316 when Yuri visited

the Golden Horde. On that occasion the khan gave

him the patent for Vladimir. He returned home

with Tatar troops to consolidate his rule, but,

when he attacked Mikhail in 1318, the latter de-

feated him. To resolve the stalemate, they rode to

Saray for a judgment. Khan Uzbek appointed Yuri

grand prince once again and had Mikhail put to

death. In 1322, while Yuri helped defend Novgorod

against the Germans, Mikhail’s successor and son

Dmitry persuaded the khan, with the usual bribes,

to give him Vladimir. After Yuri assisted the Nov-

gorodians by building a fortress on the river Neva

and by capturing Ustyug on the Northern Dvina,

he traveled to Saray to challenge Dmitry’s ap-

pointment. On November 21, 1325, Dmitry mur-

dered Yuri at the Golden Horde to avenge his

father’s death.

See also: DANIEL, METROPOLITAN; DMITRY MIKHAILOVICH;

GOLDEN HORDE; GRAND PRINCE; MOSCOW; MUSCOVY;

NOVGOROD THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fennell, John L. I. (1968). The Emergence of Moscow,

1304–1359. London: Secker and Warburg.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia, 980–1584. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

YURI VLADIMIROVICH

(d. 1157), prince of Suzdalia and grand prince of

Kiev; nicknamed “Long-arms” (“Dolgoruky”) prob-

ably because he meddled in the affairs of distant Kiev.

Yuri’s father Vladimir Vsevolodovich “Mono-

makh” gave him Suzdalia as his patrimony. In

1125 Yuri moved his capital from the older Ros-

tov to Suzdal, probably to gain more freedom

from the well-established boyar families. He also

asserted Suzdalia’s independence from Kiev, which

was ruled by his eldest brother Mstislav. In con-

solidating his rule, he founded new towns and for-

tified existing ones such as Pereyaslavl Zalessky,

Dmitrov, Yurev Polsky, Galich, Zvenigorod, and

perhaps Kostroma. He appropriated Moscow from

a local boyar. He campaigned against the Volga-

Kama Bulgars to gain control of the trade route

from the Caspian Sea, and he attempted to assert

his influence over Novgorod’s Baltic trade. Yury,

who began the tradition of building churches in

Suzdalian towns in 1152, is credited with erecting

some five churches. After his brother Mstislav died

in 1132, he became the champion of the Mono-

mashichi against the Mstislavichi (rival dynasties)

for control of Kiev. That is, in keeping with the sys-

tem of lateral succession to Kiev allegedly drawn

up by Yaroslav Vladimirovich “the Wise” in his

so-called testament, Yuri held that Monomakh’s

younger sons had prior claims over their nephews,

Mstislav’s sons. In his many battles against the lat-

ter, he was supported by the princes of Chernigov

and the Polovtsy. In 1155, after his elder brother

Vyacheslav died in Kiev, Yuri successfully seized

the town. However, he was unpopular with the

Kievans, and they poisoned him. He died on May

15, 1157.

See also: BOYAR; GRAND PRINCE; MSTISLAV; VLADIMIR

MONOMAKH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1987). “Yurii Vladimirovich Dolgo-

rukii.” The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet

History, ed. Joseph L. Wieczynski, 45:73–76. Gulf

Breeze, FL: Academic International Press.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia 980–1584. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

YURI VSEVOLODOVICH

(1189–1238), grand prince of Vladimir on the

Klyazma, in northeast Russia, when it was attacked

by the Tatars.

In 1211 Yuri’s father Vsevolod Yurevich “Big

Nest” had him marry Agafia, daughter of Vsevolod

YURI VLADIMIROVICH

1716

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Svyatoslavich “the Red,” grand prince of Kiev and

member of the Olgovich dynasty. The alliance

would serve both dynasties well. Before his death

in 1212, Vsevolod designated Yuri, the second son

in seniority, as his successor to Vladimir. Yuri’s el-

der brother Konstantin challenged his succession

and defeated Yuri and his brother Yaroslav at the

river Lipitsa in 1216. Konstantin ruled as grand

prince until his death in 1218, at which time Yuri

reclaimed Vladimir. After 1221 he sent his lieu-

tenants to Novgorod, but the townspeople rejected

them. Three years later he attempted to appease the

Novgorodians by inviting his brother-in-law

Mikhail Vsevolodovich, senior prince of the Olgo-

vich dynasty in Chernigov, to act as his mediator

with them. They accepted his offer but his brother

Yaroslav objected. Yuri therefore washed his hands

of Novgorod affairs in 1226 and turned them over

to Yaroslav. Although Yuri was less powerful than

his father had been, he took effective military ac-

tion to stop the Volga Bulgars from attacking Suz-

dalia. In 1221 he concluded peace with them. After

that, he organized campaigns against the Mordva

tribes and, in 1232, subdued them. Moreover, to

secure his eastern frontier he built the outpost of

Nizhny Novgorod. In February 1238, when the

Tatars devastated Vladimir, his wife and sons per-

ished. Later the invaders confronted Yuri and his

troops at the river Sit, where he was waiting in

vain for Yaroslav to bring reinforcements. On

March 4 of that year he fell in battle.

See also: GOLDEN HORDE; GRAND PRINCE; NOVGOROD THE

GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dimnik, Martin. (1987). “Yurii (Georgii) Vsevolodovich.”

The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History,

ed. Joseph L. Wieczynski. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic

International Press.

Fennell, John. (1983). The Crisis of Medieval Russia

1200–1304. London: Longman.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

YURI VSEVOLODOVICH

1717

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ZADONSHCHINA

Zadonshchina (roughly, The Battle Beyond the Don)

is the conventional title for a medieval literary work

about the historically important Battle of Kulikovo

Field (1380). Written some years after the historical

event, in the late fourteenth or possibly the begin-

ning of the fifteenth century, it is attributed in one

of the surviving copies to a Sofonia of Ryazan about

whom nothing is known. The text is preserved in a

longer and a shorter redaction, giving rise to the

usual arguments in these cases over which was the

“original.” Primacy is important to the crucial ques-

tion of Zadonshchina’s relationship to the Lay of Igor’s

Campaign. The short redaction appears to be an in-

complete extract and not the author’s text.

There can be no doubt of a close association

with the Lay in view of extensive similarities that

go beyond any mutual dependence on some third

source or tradition. Zadonshchina was almost cer-

tainly written as an imitation of the Lay and a re-

sponse to it, treating the victory at Kulikovo as

revenge for the defeat of Igor at the hands of a dif-

ferent steppe enemy. The writer sought to reverse

circumstances of 1185 as described in the Lay, turn-

ing Igor’s unsuccessful campaign upside down, so

to speak. In the process he distorted history: For

example, by exaggerating the unity of the princes

in 1380 in order to counterbalance the disunity of

1185. Most of his figures of speech are borrowed

from the Lay and often ineptly combined and

overused. For these reasons, Zadonshchina is con-

sidered derivative and inferior.

See also: FOLKLORE; LAY OF IGOR’S CAMPAIGN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jakobson, Roman, and Worth, Dean S., eds. (1963). So-

fonija’s Tale of the Russian-Tatar Battle on the Kulikovo

Field. The Hague: Mouton.

Zenkovsky, Serge A., tr. and ed. (1974). Medieval Rus-

sia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales, 2d ed. rev. New

York: Dutton.

N

ORMAN

W. I

NGHAM

ZAGOTOVKA

State agricultural procurement.

The term zagotovka refers to the process through

which agricultural products (e.g., grain) were pro-

Z

1719

cured by the Soviet state, usually from collective

farms (kolkhozes) in the form of compulsory de-

liveries (obyazatelnye postavki) at low prices set by

the state. The procurement process was important

in that the underpinning of the Soviet strategy of

industrialization was the extraction of grain and

other agricultural products from the countryside

for use as a source of domestic food and as a means

to finance industrialization through export. More-

over, beginning under Lenin during the period of

War Communism, when forced requisitioning (pro-

drazverstka) was introduced, the role of the state in

the production, acquisition, and distribution of

agricultural products increased, especially after the

collectivization of agriculture in the late 1920s.

In addition to the earlier use of forced requisi-

tioning and the subsequent introduction of compul-

sory deliveries extracted from collective farms,

deliveries were also made by state farms (sdacha

sovkhozov), payments in kind (naturoplata) were re-

quired for the services of the Machine Tractor Sta-

tions (MTS), and taxes in kind (prodnalog) were levied.

The mechanisms of procurement introduced by

the Soviet state served, in part, to eliminate the

market of the New Economic Policy (NEP) of the

1920s in order to organize the interaction between

the agricultural and the industrial (urban) sector.

Moreover, as state controls replaced the NEP mar-

ket, the terms of trade between the countryside and

the urban industrial sector could increasingly be

dictated by the state.

See also: AGRICULTURE; ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; IN-

DUSTRIALIZATION, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure, 7th ed.

New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Volin, Lazar. (1970). A Century of Russian Agriculture.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

R

OBERT

C. S

TUART

ZASEKA See FRONTIER FORTIFICATIONS.

ZASLAVSKAYA, TATIANA IVANOVNA

(b. 1927), economist and influential sociologist.

Tatiana Ivanovna Zaslavskaya graduated from

the Economics Faculty of Moscow University in

1950 and became a member of the Communist

Party in 1954. She completed a doctoral thesis

for the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of

Economics, Department of Agriculture, where she

worked until 1963. In that year, Zaslavskaya

moved to the Novosibirsk Institute of Industrial

Economics to work with Abel Aganbegyan. She

subsequently became head of the Institute’s Soci-

ology Department, in 1968. At the same time, Za-

slavskaya became a corresponding member of the

Russian Academy of Sciences, becoming a full

member in 1981. From the late 1960s she headed

the Social Problems department of the Siberian

branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, where

she remained until the mid-1980s. During this pe-

riod, Zaslavskaya developed a model capable of pre-

dicting trends in Soviet agriculture.

Zaslavskaya came to prominence in early

1980s, when her Novosibirsk report was leaked to

the public. Later on, when Mikhail Gorbachev was

introducing his policies of glasnost and perestroika,

Zaslavskaya became a key player and senior gov-

ernment adviser in the field of socioeconomic and

agricultural reform, from 1985 to 1987. She was

elected to the Congress of People’s Deputies in 1989

as Russian Academy of Sciences representative. In

1986 Zaslavskaya was elected President of the So-

viet Sociological Association, before moving on to

head to the new Institute of Sociology in 1987 and

the Centre for the Study of Public Opinion (VTs-

IOM) in 1988. In 1990 Boris Yeltsin elected Za-

slavskaya to his consultative council. Since then

Zaslavskaya has gone on to become head of the

Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; NOVOSIBIRSK REPORT;

PERESTROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Yanowitch, Murray, ed. (1989). Voices of Reform: Essays

by Tatiana I. Yaslavskaya. Armonk, NY and London:

M. E. Sharpe.

C

HRISTOPHER

W

ILLIAMS

ZASULICH, VERA IVANOVNA

(1849–1919), Russian revolutionary.

Born into a relatively poor noble family, Vera

Ivanovna Zasulich became a populist as a young

woman. She had a keen sense of social justice, sym-

ZASEKA

1720

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

pathized with the downtrodden and the oppressed,

and opposed autocracy. An active participant in the

populist movement, she was imprisoned from 1869

to 1871 and was in administrative (internal) exile

from 1871 to 1875. She spent most of her life in

poverty and poor health, with a bohemian lifestyle.

Her partner, Lev Deich, was arrested in 1884 for

smuggling revolutionary literature to Russia and

was exiled to Siberia, where he remained until 1901.

While in Siberia, he married another woman. Za-

sulich achieved fame and heroine status for shoot-

ing Fyodor Trepov (Governor of St. Petersburg) in

1878, in an assassination attempt (Trepov survived).

Acquitted at a jury trial, she fled abroad to escape

rearrest and lived in political exile (in Switzerland,

France, the United Kingdom, and Germany) from

1878 to 1905 (with the exception of two brief re-

turns to Russia for four months in 1879–1880 and

for three months in 1899–1900). She corresponded

with Karl Marx and was a friend of Friedrich En-

gels. She was one of the founders of the first Russ-

ian Marxist organization, the Liberation of Labor

(Osvobozhdenie truda) group in Geneva in 1883. Au-

thor of numerous books, articles, and translations,

she was an editor of Iskra (“Spark”) from 1900 to

1905. A participant in the 1903 second congress of

the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, she

helped found the Menshevik movement and made

frequent attempts to reconcile factions of the revo-

lutionary movement. After 1905 Zasulich retired

from revolutionary activities. She was in her late

fifties, in poor health, and there was an amnesty for

political exiles. She subsequently supported Russian

participation in World War I. As an old Menshevik

and supporter of the war, she naturally opposed the

October Revolution.

See also: ENGELS, FRIEDRICH; MARXISM; MENSHEVIKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergman, Jay. (1983). Vera Zasulich. Stanford, CA: Stan-

ford University Press.

Shanin, Teodor, ed. (1983). Late Marx and the Russian

Road: Marx and “The Peripheries of Capitalism.” New

York: Monthly Review Press.

M

ICHAEL

E

LLMAN

ZEALOTS OF PIETY

The Zealots of Piety (1646–1653) were a group

of clergy and laity who energetically sought to

elevate the religious consciousness and spiritual life

of the people by reforming popular religious prac-

tices, improving the liturgy, introducing sermons,

and strengthening the role of the clergy. The re-

formers gathered around Stefan Vonifatiev, arch-

priest of the Annunciation Cathedral in the Kremlin

and confessor to Tsar Alexis Mikhailovich. Individ-

uals associated with the Zealots included leading

figures at court, such as the Boyar Boris Ivanovich

Morozov and gentrymen (dvoryane) Fyodor

Rtishchev and Simeon Potemkin. The head of the

Printing Office, Prince Alexei Mikhailovich Lvov,

supported the Zealots, as did several of the correc-

tors (spravshchiki), including Mikhail Rogov (arch-

priest at the Archangel Cathedral), Ivan Nasedka

(priest at the Dormition Cathedral) and Shestak

Martemianov (layman). Nikon, archimandrite of

the New Savior Monastery in Moscow (patriarch

from 1652) was also a participant. Ivan Neronov,

a provincial reformer, became archpriest of the

Kazan Cathedral in Moscow in 1649 and took his

place among the Zealots of Piety. Other represen-

tatives of the provincial secular clergy active in the

group included the archpriests Avvakum of Yurev,

Daniil of Temnikov, Login of Murom, and Daniil

of Kostroma. Traditional historiography opposed

the Zealots to Patriarch Iosif and the Church Coun-

cil, although some historians have questioned this

opposition. Nikon, a leading Zealot, became patri-

arch in 1652, and his actions split the circle. Av-

vakum led several members of the group in

opposition that ultimately led to schism and the

emergence of Old Belief.

See also: AVVAKUM PETROVICH; MOROZOV, BORIS IVANO-

VICH; NERONOV, IVAN; NIKON, PATRIARCH; OLD BE-

LIEVERS; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lobachev, S.V. (2001). “Patriarch Nikon’s Rise to Power.”

Slavonic and East European Review 79(2):290–307.

C

ATHY

J. P

OTTER

ZEMSKY NACHALNIK See LAND CAPTAIN.

ZEMSKY SOBOR See ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND.

ZEMSTVO

Zemstvo was a system of local self-government

used in a number of regions in the European part

of Russia from 1864 to 1918. It was instituted as

ZEMSTVO

1721

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

a result of the zemstvo reform of January 1, 1864.

This reform introduced an electoral self-governing

body, elected from all class groups (soslovii), in dis-

tricts and provinces. The basic principles of the

zemstvo reform were electivity, the representation

of all classes, and self-government in the questions

concerning local economic needs.

The statute of January 1, 1864, called for the

institution of zemstvos in thirty-four provinces of

the European part of Russia. The reform did not

affect Siberia and the provinces of Archangel, As-

trakhan, and Orenburg, where there were very few

noble landowners. Neither did the reform affect re-

gions closest to the national borders: the Baltic

States, Poland, the Caucasus, Kazakhstan, and Cen-

tral Asia.

According to the statute, zemstvo institutions

in districts and provinces were to consist of zem-

stvo councils and executive boards. The electoral

system was set up on the basis of class and pos-

sessions. Every three years, the citizens of a district

elected between fourteen to one hundred or so

deputies to the council. The elections were held in

curias (divisions), into which all of the districts’

population was divided. The first curia consisted of

landowners who possessed 200 or more desiatinas

of land (about 540 acres), or other real estate worth

at least 15,000 rubles, or had a monthly income

of at least 6,000 rubles. This curia consisted mainly

of nobles and landlords, but members of other

classes (merchants who bought nobles’ land, rich

peasants who acquired land, and the like) eventu-

ally grew more and more prominent. The second

curia consisted of city dwellers who possessed mer-

chant registration, or who owned trading and in-

dustrial companies with a yearly income of at least

6,000 rubles, or held real estate in worth at least

500 rubles (in small cities) or 2,000 rubles (in large

cities). The third curia consisted mainly of repre-

sentatives of village societies and peasants who did

not require a special possession permit. As a result

of the first of these elections in 1865 and 1866, no-

bles constituted 41.7 percent of the district deputies,

and 74 percent of the province deputies. Peasants

accounted for 38.4 and 10.6 percent, and mer-

chants for 10.4 and 11 percent. The representatives

of district and provincial assemblies were the dis-

trict and provincial marshals of nobility. Zemstvo

assemblies became governing institutions: They

elected the executive authorities: the provincial and

district executive boards (three or five people).

The power of the zemstvo was limited to local

tasks (medicine, education, agriculture, veterinary

services, roads, statistics, and so on). Zemstvo taxes

ensured the budget of zemstvo institutions. The

budget was to be approved by the zemstvo assem-

bly. It was compiled, mainly, from taxes on real

estate (primarily land), and in this case the pres-

sure was mainly on peasant land. Within the

limits of their power, zemstvos had relative inde-

pendence. The governor could only oversee the le-

gitimacy of the zemstvo’s decisions. He also

approved the chairman of the uezd executive board

and the members of the provincial and uezd exec-

utive boards. The chairman of the provincial exec-

utive board had to be approved by the minister of

the Interior.

As a result of the zemstvo counterreform of

1890, the governor gained the right not only to

oversee the reasonableness of the zemstvo’s deci-

sions. A special supervising institution was created,

called the Governor’s Bureau of Zemstvo Affairs.

Over half of the voters in 1888 were bereft of elec-

toral rights. The composition of zemstvo assem-

blies was changed in favor of the nobles. In the

1897 zemstvo elections, nobles constituted to 41.6

percent of district deputies and 87.1 percent of

provincial deputies. The peasants obtained 30.98

and 2.2 percent.

The structure of zemstvo institutions contained

no “minor zemstvo unit,” understood to mean a

volost (rural district) unit that would be closest to

the needs of the local population of all classes. Nei-

ther was there a national institution that would

coordinate the activity of local zemstvos. In the end,

zemstvos became “a building without a foundation

or a roof.” The government opposed cooperation

between zemstvos, fearing constitutionalist atti-

tudes. Zemstvos did not have their own institution

of compulsory power, which made them rely on

the administration and police. All this soon made

zemstvos stand in opposition to autocracy. They

were especially active in the 1890s, when a so-

called third element (professionals employed by

zemstvos, or predominantly democratic members

of the intelligentsia) became influential. In the early

twentieth century, liberal zemtsy became overtly

political, and in 1903 they formed the illegal

“Union of Constitutionalist-Zemtsy.” In November

of 1904, an all-Russian assembly of zemstvos was

held in St. Petersburg, and a program of political

reforms was developed, including the creation of a

national representation with legislative rights.

Later, many members of the movement joined the

leading liberal parties, the Constitutional Demo-

crats and the Oktobrists.

ZEMSTVO

1722

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

By 1912 zemstvos had established 40,000 pri-

mary schools, approximately 2,000 hospitals, a

network of libraries, reading halls, pharmacies, and

doctors’ centers. Their budget increased to 45 times

its 1865 level, amounting to 254 million rubles. In

1912, 30 percent of zemstvo expenditure went to

education, 26 percent went to healthcare, 6.3 per-

cent went to the development of local agriculture

and the local economy, and 2.8 percent went to

veterinary services. In 1912 zemstvos employed

approximately 150,000 specialist teachers, doctors,

agriculturists, veterinarians, statisticians, and oth-

ers. By 1916 zemstvos were operating in 43 of the

93 provinces and regions.

After the beginning of World War I, on August

12, 1914, zemstvos created the National Union of

Zemstvos in aid to sick and wounded soldiers. In

1915 this Union united with the National Union of

Cities. For the coordination of the two organiza-

tions, a special committee called “Zemgor” was cre-

ated. Besides aiding the wounded, it also helped

supply the army and helped refugees. After the

March Revolution of 1917 the Zemgor chairman,

prince Georgy Lvov, became the prime minister of

the Provisional Government. The chairmen of the

zemstvo executive boards were appointed the

plenipotentiaries of the Provisional Government in

their districts and provinces. Zemstvos were insti-

tuted in 19 more provinces and regions of Russia

and volost zemstvos were created, forming the low-

est institutions of local self-government. Re-elections

were held in all levels of the zemstvo on the basis

of universal, direct, equal, and secret voting. After

the October Revolution, on January 17, 1918, by

decree of the Soviet Government (Sovnarkom), the

main committees of the Zemstvo and City Unions

were dismissed and their possessions were given to

the Supreme Council of National Economy. By July

1918 zemstvos in the territories controlled by the

Bolsheviks were removed, but were reinstated in ter-

ritories controlled by the White Armies and abroad.

In 1921 a Committee of Zemstvos and Cities, once

again called Zemgor, was established in Paris to

provide aid to Russian citizens living abroad. Divi-

sions of the Zemgor also operated in Prague and the

Balkans. The Paris Zemgor exists to this day.

See also: LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Eklof, Ben, Bushnell John, and Zakharova Larissa, eds.

(1994). Russia’s Great Reforms, 1855–1881. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Emmons, Terence, and Vucinich, Wayne S., eds. (1982).

The Zemstvo in Russia: An Experiment in Local Self-

Government. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Starr, Frederick S. (1972). Decentralization and Self-

Government in Russia, 1830–1870. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Zaionchkovskii, Petr Andreevich. (1976). The Russian Au-

tocracy under Alexander III. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic

International Press.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

ZERO-OPTION

Originally conceptualized in 1979 by the Social De-

mocratic party of West Germany, the concept of a

“zero option” led to the first, albeit more symbolic

than substantive, nuclear disarmament treaty be-

tween the United States and the Soviet Union. Al-

though it began as a simplistic rhetorical slogan

among West German anti-nuclear activists, the

concept of having zero nuclear missiles on the Eu-

ropean Continent was embraced by U.S. President

Ronald Reagan and eventually codified as the In-

termediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

On November 18, 1981, Reagan announced the

United States’ support for canceling the deploy-

ment of intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Eu-

rope, in exchange for Soviet withdrawal of nuclear

missiles already positioned in its Eastern European

satellite states. Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev im-

mediately dismissed the idea, noting its asymmetric

nature: The Soviets were being asked to dismantle

an entire class of weapons (from Asia as well as

Europe) in exchange for the United States’ non-

deployment in Europe alone. As a result of a con-

tinued stalemate, Reagan ordered the deployment

of nuclear missiles into Western Europe in 1983.

Neither Reagan nor Brezhnev and his successors,

Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, were

willing to compromise.

Credit for the eventual success of the zero-option

concept, as solidified through the signing of the INF

Treaty, rests largely in the hands of Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev, who applied a new spirit to So-

viet foreign policy. Gorbachev offered a series of uni-

lateral concessions that essentially meant acceptance

of a final treaty mirroring Reagan’s initial 1981 pro-

posal. Ironically, as the 1980s progressed and the

INF Treaty gained political momentum, it was the

Western European nations that balked, voicing fears

about Soviet conventional superiority in Europe.

ZERO-OPTION

1723

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Such fears were quelled by the non-inclusion of

British and French nuclear weapons in the final

treaty, which was signed by the United States and

the Soviet Union on December 8, 1987.

See also: ARMS CONTROL; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYE-

VICH; INTERMEDIATE RANGE; NUCLEAR FORCES TREATY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bennett, Paul R. (1989). The Soviet Union and Arms Con-

trol: Negotiating Strategy and Tactics. Westport, CT:

Praeger Publishers.

Risse-Kappen, Thomas. (1988). The Zero Option: INF, West

Germany, and Arms Control, tr. Lesley Booth. Boul-

der, CO: Westview Press.

M

ATTHEW

O’G

ARA

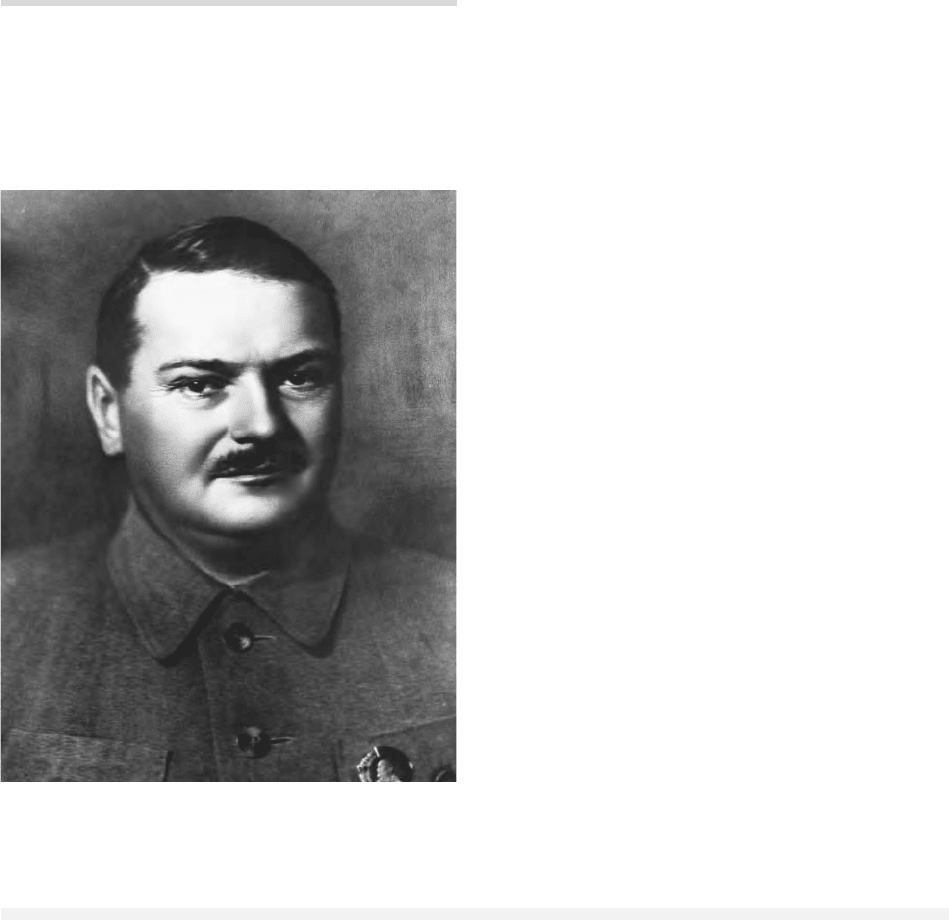

ZHDANOV, ANDREI ALEXANDROVICH

(1896–1948), Soviet political leader.

Andrei Zhdanov was one of Stalin’s most

prominent deputies and is best known as the leader

of the ideological crackdown following World War

II. After the assassination of Leningrad leader Sergei

Kirov in 1934, Zhdanov became head of the Lenin-

grad party organization. Also in 1934 he became

a secretary of the party’s Central Committee and

in 1939 a full Politburo member. He spent most of

World War II leading Leningrad, which was be-

sieged by Hitler’s troops.

Zhdanov was transferred to Moscow in 1944

to work as Central Committee secretary for ideol-

ogy and began playing a growing leadership role,

which intensified his rivalry with Central Com-

mittee Secretary Georgy Malenkov. Zhdanov, as

chief of the Central Committee’s Propaganda De-

partment, became identified with official ideology,

while Malenkov, chief of the party’s personnel and

industrial departments, was identified with man-

agement of party activity and industry. In the ma-

neuvering between these leaders, Zhdanov scored a

victory over his rival by starting an ideological

crackdown in August 1946, denouncing deviations

by some literary journals and harshly assailing

prominent writers. During Zhdanov’s campaign,

Malenkov lost his leadership posts and fell into

Stalin’s disfavor, while Zhdanov became viewed as

Stalin’s most likely successor.

Zhdanov’s role in the harsh postwar ideologi-

cal crackdown earned him the reputation of the

regime’s leading hardliner; the wave of persecution

of literary and cultural figures became known as

the Zhdanovshchina. In June 1947 Zhdanov de-

nounced ideological errors and softness toward the

West in Soviet philosophy. At a September 1947

conference of foreign communist parties, Zhdanov

laid out the thesis that the world was divided into

two camps: imperialist (Western) and democratic

(Soviet). Zhdanov’s pronouncements fostered de-

velopment of the Cold War and an assertion of ba-

sic hostility between Soviet and Western ideas.

However, the worst excesses of the Zhdanov-

shchina ironically were committed after Zhdanov’s

death and were directed against Zhdanov’s allies.

Zhdanov refused to back biologist Trofim Ly-

senko’s attacks on modern genetics, and Zhdanov’s

son, who was head of the Central Committee’s Sci-

ence Department, actually denounced Lysenko’s

ideas in April 1948 and was later forced to recant

publicly. In July 1948 Zhdanov was sent off for

an extended vacation, during which he died on Au-

gust 31, 1948. Malenkov returned to power in

mid-1948, and, as Zhdanov was dying in August

1948, Lysenko was given free reign in science and

ZHDANOV, ANDREI ALEXANDROVICH

1724

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Andrei Zhdanov, leader of the Leningrad Communist Party

from 1934 to 1948. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

initiated the condemnation of genetics and other al-

legedly pro-Western scientific ideas. In 1949 a cam-

paign against Jews as cosmopolitans began. Also

in 1949 Zhdanov’s proteges in Leningrad were

purged (the Leningrad Case), many of them even-

tually executed. Zhdanov himself was spared pub-

lic disgrace, unlike his proteges and his Leningrad

party organization, which was cast into disfavor

for years. Zhdanov continued to be treated as a

hero, and when Stalin concocted the Doctors’ Plot

in 1952, he cast Zhdanov as one of the victims of

the Jewish doctors, who allegedly had poisoned the

Leningrad leader.

Although the symbol of intolerance in litera-

ture and culture and of hostility toward the West,

Zhdanov was probably no more hard-line than

his rivals. His denunciations of ideological devia-

tions appeared largely motivated by his struggle to

retain Stalin’s favor. But Stalin turned to a crack-

down and a break with the West and drove the

Zhdanovshchina into its extremes of anti-Semitism,

Lysenkoism, and the execution of Leningrad lead-

ers and Zhdanov proteges.

See also: JEWS; LYSENKO, TROFIM DENISOVICH; MALENKOV,

GEORGY MAXIMILYANOVICH; PURGES, THE GREAT;

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Graham, Loren. (1972). Science and Philosophy in the So-

viet Union. New York: Knopf.

Hahn, Werner G. (1982). Postwar Soviet Politics: The Fall

of Zhdanov and the Defeat of Moderation, 1946–53.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Medvedev, Zhores. (1969). The Rise and Fall of T.D. Ly-

senko. New York: Columbia University Press.

W

ERNER

G. H

AHN

ZHELYABOV, ANDREI IVANOVICH

(1851–1881), Russian revolutionary narodnik

(populist) and one of the leaders of the People’s Will

party.

Andrei Zhelyabov was born in the village of

Sultanovka in the Crimea to the family of a serf.

He graduated from a gymnasium in Kerch with a

silver medal (1869) and attended the Law Depart-

ment of the Novorossiysk University in Odessa. He

was expelled in November of 1871 for being in-

volved in student-led agitation, and was sent home

for one year. Upon returning to Odessa, in 1873

and 1874 he was a member of the Chaikovsky cir-

cle and spread revolutionary propaganda among

workers and the intelligentsia. In November 1874,

he was arrested but bailed out before the trial.

Zhelyabov faced charges of revolutionary propa-

ganda as part of the Trial of 193 (1877–1878) in

St. Petersburg. He was declared innocent on the ba-

sis of insufficient evidence. After his release, he lived

in Ukraine, where he spread revolutionary propa-

ganda among the peasants.

Disappointed with the ineffectiveness of his

propaganda, Zhelyabov concluded that it was nec-

essary to lead a political struggle. In June 1879 he

took part in the Lipetsk assembly of terrorist politi-

cians and was one of the authors of the formula-

tion of the necessity of violent revolt through

conspiracy. He joined the populist organization

Zemlya i Volya (Land and Freedom) and became one

of the leaders of the Politicians’ Faction. After the

split of Zemlya i Volya in August 1879, Zhelyabov

joined the People’s Will and became a member of

its executive committee. On August 26, 1879, he

took part in the session of the executive commit-

tee where emperor Alexander II was sentenced to

death. He supervised the preparation of the assaults

on Alexander II near Alexandrovsk in the Yekater-

inoslav province in November 1879, where an at-

tempt was made to blow up the tsar’s train.

Zhelyabov also supervised the assault on the tsar

in the Winter Palace on February 17, 1880, and an

unsuccessful attempt to blow up Kamenny Most

(Stone Bridge) in St. Petersburg while the tsar was

passing there in August 1880.

Zhelyabov took part in the devising of all pro-

gram documents of the party. He is also credited

with the creation of the worker, student, and mil-

itary organizations of the People’s Will. He was one

of the main organizers of the tsar’s murder on

March 13, 1881, but on the eve of the assault he

was arrested. On March 14, he submitted a plea to

associate him with the tsar’s murder. During the

trial, Zhelyabov, who refused to have a lawyer,

made a programmatic speech to prove that the gov-

ernment itself, with its inappropriately repressive

means of dealing with peaceful propagandists of

socialist ideas, forced them to take the path of ter-

rorism. Zhelyabov was sentenced to death and

hanged on April 15, 1881, at the Semenovsky pa-

rade ground in St. Petersburg.

See also: ALEXANDER II; LAND AND FREEDOM PARTY; PEO-

PLE’S WILL, THE

ZHELYABOV, ANDREI IVANOVICH

1725

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Figner, Vera. (1927). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. New

York: International Publishers.

Footman, David. (1968). Red Prelude: A Life of A. I.

Zhelyabov. London: Barrie & Rockliff; The Cresset

Press.

Venturi, Franco. (1983). Roots of Revolution: A History of

the Populist and Socialist Movements in Nineteenth Cen-

tury Russia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

O

LEG

B

UDNITSKII

ZHENOTDEL

The Women’s Section of the Central Committee of

the Communist Party (1919–1930).

In November 1918 Alexandra Kollontai, Inessa

Armand, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Konkordia Samoil-

ova, Klavdia Nikolayeva, and Zlata Lilina organized

the First National Congress of Women Workers and

Peasants. This was not actually the first national

women’s congress, as Russian feminists had held

a huge conference in St. Petersburg in December

1908. Kollontai and her comrades, however, ex-

plicitly rejected any parallels to the earlier confer-

ence, arguing that they sought not to separate

women’s issues from men’s but rather to weld and

forge women and men into the larger socialist lib-

eration movement. Despite serious ambivalence over

whether to create a separate women’s organization,

the Congress passed a resolution requesting the

party Central Committee to organize “a special

commission for propaganda and agitation among

women.” The organizers limited their designs for

this commission, however, initially claiming that

it would serve “merely as a technical apparatus”

for implementing Central Committee decrees. This

was not, they insisted, a feminist organization.

The Central Committee now sanctioned the for-

mal creation of women’s commissions at the local

and central levels. In September 1919 the Central

Committee passed a decree upgrading the commis-

sions to the status of sections (otdely) within the

party committees, thus creating the zhenotdel, or

women’s section.

Several factors played into the creation of the

women’s sections. The top leadership of the party,

including Vladimir Ilich Lenin, were well aware of

the German Women’s Bureau and International

Women’s Secretariat created by Clara Zetkin and

the German Social Democratic Party. Many of the

top women Bolsheviks (especially Kollontai and Ar-

mand) had begun their social activism by working

among women, while others (including Krupskaya,

Samoilova, Nikolayeva, and Lilina) had worked on

the party’s journal The Woman Worker (Rabotnitsa)

in 1913 and 1914.

One reason motivating Kollontai in particular

as early as the spring of 1917 was a fear that if

the Bolshevik Party did not organize an effective

women’s movement, Russian women living under

conditions of war and privation might well be

drawn into the remnants of the prerevolutionary

feminist or Menshevik movements. Related to that

was a persistent anxiety among Bolsheviks of all

outlooks that if they did not recruit women into

the official party, their (i.e., women’s) backward-

ness would make them easy targets for all manner

of counterrevolutionary forces. Finally, and per-

haps most importantly, the early party-state des-

perately needed to mobilize every woman and man

to support the Red Army in the Civil War.

Nonetheless, the ambivalence of the 1918 Con-

gress dogged the women’s section for the whole of

its existence. The leaders themselves expressed am-

bivalence about the project on which they were em-

barking. Were they creating special sections and

special conferences so that, in the long run, they

could eliminate the need for such sections and con-

ferences? Many female activists, moreover, had

personally chosen socialist organizing and activism

because they sought an escape from gender stereo-

typing; they did not want to be thought of as

women, let alone as professionally responsible for

women’s advancement.

From the outset the top leadership of the

zhenotdel faced a wide range of organizational

problems. These included constant turnover of their

personnel as their best members were siphoned off

for other projects; communication difficulties be-

tween Moscow and the regions; resistance of rural

and urban women to outside organizers; and re-

sistance of male party members who thought this

work completely unnecessary.

Despite all these difficulties the zhenotdel made

significant gains in the area of organization-building

during the period from 1919 to 1923. Often work-

ing in special interdepartmental commissions, they

established relations with the Maternity and Infant

Section (OMM) of the Commissariat of Health, as

well as with the Commissariats of Education, Labor,

Social Welfare, and Internal Affairs. They addressed

issues of abortion and motherhood, prostitution,

child care, labor conscription, female unemploy-

ZHENOTDEL

1726

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY