Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

his complaints until after the upcoming celebration

for the seventieth anniversary of the October Rev-

olution so that a united front would lead the fes-

tivities. Yeltsin declined to heed this advice.

Yeltsin aired his grievances at the Central Com-

mittee Plenum on October 21, 1987. The plenum

agenda included approving Gorbachev’s anniver-

sary speech, but that was not the presentation that

attracted the most attention. Following Gor-

bachev’s presentation, Yeltsin delivered an im-

promptu speech, lasting for about ten minutes,

complaining about the slow pace of reforms, Lig-

achev’s intrigues, and a new cult of personality

emerging around Gorbachev. Yeltsin charged that

leaders were sheltering Gorbachev from the harsh

realities of Soviet life. Though this secret speech was

not published at the time, its contents soon became

public. The plenum itself turned into three hours

of criticism heaped on Yeltsin. He was criticized not

so much for the content as for the style and the

timing of his comments. Yeltsin regularly had op-

portunities to voice such concerns at weekly Polit-

buro meetings; that he had chosen this particular

forum against the direct order of Gorbachev indi-

cated Yeltsin’s immaturity and arrogance. Gorbachev

now accepted Yeltsin’s prior resignation from the

Moscow Party Committee and asked the Central

Committee to enact appropriate resolutions for his

removal. He was also stripped of his seat on the

Politburo. Yeltsin thus became the first high-level

Gorbachev appointee to lose his position.

Yeltsin was not exiled back to Siberia, how-

ever. Gorbachev appointed Yeltsin to be first

deputy chair of the USSR State Committee for Con-

struction, a post that allowed him to remain in

Moscow and in the political limelight. Yeltsin also

remained popular with Muscovites, many of

whom felt they had lost an ally. Almost one thou-

sand residents of the capital staged a rally to sup-

port Yeltsin, which had to be broken up by police.

Yeltsin was unavailable. As would frequently oc-

cur during his political career, times of high polit-

ical drama tended to incapacitate him. At the time

of the Central Committee Plenum, Yeltsin was hos-

pitalized for an apparent heart attack. He was lit-

erally taken from his hospital bed to attend the

session of the Moscow City Committee to be for-

mally fired.

Yeltsin reappeared in public at the 1988 May

Day celebration, joining other Central Committee

members to watch the annual parade. He was se-

lected as a delegate from the Karelian Autonomous

Socialist Republic for the extraordinary Nineteenth

CPSU Conference in June; Party officials may have

selected the remote constituency to reduce public-

ity for Yeltsin. Instead, the publicity came on the

last day of the Conference.

Gorbachev allowed Yeltsin to speak at the Con-

ference in order to clear the air of rumors regard-

ing the October affair and to see what this “man

of the people” had to say. On live television, Yeltsin

began by responding to criticisms recently levied

against him by his fellow delegates and then tried

to clarify his physical and mental condition at the

Moscow City Plenum. He repeated his criticism of

the slow pace of reform and of privileges for the

Party elite. Then, for the first time in Soviet his-

tory, a disgraced leader publicly asked for rehabil-

itation. Yeltsin was followed to the podium by

Ligachev, who continued to criticize and denigrate

the fallen Communist. When the Conference ended,

Yeltsin had not been reinstated. But in a move sug-

gesting that Gorbachev had some respect for

Yeltsin’s point of view, Ligachev was soon reas-

signed to agriculture.

RISING DEMOCRAT

Yeltsin began a remarkable political comeback with

the March 1989 elections to the first USSR Con-

gress of People’s Deputies (CPD). Although the Cen-

tral Committee declined to put Yeltsin on its slate

of candidates, some fifty constituencies nominated

him. Yeltsin opted to run from Moscow—not

Sverdlovsk—and won almost 90 percent of the

vote, despite an official smear campaign. When the

CPD announced candidates for the new Supreme

Soviet, Yeltsin was not on the ballot. Large popu-

lar protests began in Moscow, and delegates were

swamped with telegrams and telephone calls sup-

porting Yeltsin. Ultimately Alexei Kazannik, a

deputy from Omsk, offered to relinquish his seat

to Yeltsin—and Yeltsin only. Yeltsin became co-

chair of the opposition Inter-Regional Group and

called for a new constitution that would place sov-

ereignty with the people, not the Party. Further sig-

naling his break with Gorbachev, during the July

1990 Twenty-eighth Party Conference, Yeltsin dra-

matically resigned from the CPSU, tossing his party

membership card aside and striding out of the

meeting hall. He had cast his lot with the Russian

people.

Meanwhile, Yeltsin had established roots in the

RSFSR, giving him a political base to challenge Gor-

bachev. He was elected to the Russian Congress of

YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

1706

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

People’s Deputies in March 1990 and became chair

of the Russian Supreme Soviet in May 1990. He

declared Russia sovereign in June 1990, triggering

a war of laws between his institutions and those

of Gorbachev. In June 1991 Yeltsin was elected to

the newly created office of RSFSR President. Unlike

Gorbachev as president of the USSR, Yeltsin had

been popularly elected, a mandate that gave him

much greater legitimacy than Gorbachev could

claim for himself. He even called for Gorbachev’s

resignation in February 1991. During the negotia-

tions for a new union treaty in early 1991, Yeltsin

demanded that key powers devolve to the republics.

Eventually the two leaders came to an agreement,

and Yeltsin planned to sign the new Union Treaty

on August 20, 1991.

When hard-line communists tried to block the

treaty and topple Gorbachev, Yeltsin sprang into ac-

tion. While Gorbachev was under house arrest in

the Crimea, Yeltsin was at his dacha outside Moscow.

Refusing his family’s and advisers’ pleas that he go

into hiding, Yeltsin eluded the commandos sur-

rounding his dacha and went to the Russian par-

liament building, known as the White House.

Climbing atop one of the tanks surrounding the

White House, Yeltsin denounced the coup as illegal,

read an Appeal to the Citizens of Russia, and called

for a general strike. Yeltsin’s team began circulat-

ing alternative news reports, faxing them out to

Western media for broadcast back into the USSR.

Soon Muscovites began to heed Yeltsin’s call to de-

fend democracy. Thousands surrounded the build-

ing, protecting it from an expected attack by

hard-line forces. Throughout the three-day siege,

Yeltsin remained at the White House, broadcasting

radio appeals, telephoning international leaders, and

regularly addressing the crowd outside. When the

coup plotters gave up, Yeltsin had replaced Gor-

bachev as the most powerful political figure in the

USSR. Yeltsin banned the CPSU on Russian soil, ef-

fectively endings its operations, but did not call for

purges of communist leaders. Instead, he left for his

own three-week Crimean vacation.

While Yeltsin inexplicably left the capital at this

critical time, Gorbachev was unable to rally sup-

port to himself or his reconfigured Soviet Union.

Upon his return to Moscow, Yeltsin seized more

all-union assets, institutions, and authorities until

it became obvious that Gorbachev had little left to

govern. Then, on the weekend of December 8, 1991,

Yeltsin met with his counterparts from Belarus

(Stanislau Shushkevich) and Ukraine (Leonid

Kuchma). The three men drafted the Belovezhskaya

Accords, in which the three founding republics of

the Soviet Union declared the country’s formal end.

THE STRUGGLE FOR RUSSIA

Yeltsin began the simultaneous tasks of establish-

ing a new state, a market economy, and a new po-

litical system. Initially the new Commonwealth of

Independent States (CIS) served to regulate relations

with the other Soviet successor states, although

Ukraine and other western states resented Yeltsin’s

argument that Russia was first among equals.

Yeltsin, for example, commanded the CIS military,

which he initially used in lieu of creating a sepa-

rate Russian military. Domestically, he faced se-

cessionist challenges from Chechnya and less

severe autonomist movements from Tatarstan,

Sakha, and Bashkortostan. Radical economic policy

was implemented as Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar’s

economic shock therapy program freed most prices

as of January 1, 1992, and Anatoly Chubais led

efforts to privatize state-owned enterprises. The

two policies combined to bring Russia to the brink

of economic collapse. Not only did Yeltsin face pub-

lic criticism on the economy, but his own vice pres-

ident, Alexander Rutskoi, and the speaker of

parliament, Ruslan Khasbulatov, also denounced

his policies.

On the political front, Yeltsin found himself in

uncertain waters. Although work was underway

to draft a new constitution, the process had been

interrupted by the collapse of the USSR. Russia

technically still operated under the 1978 constitu-

tion, which vested authority in the Supreme So-

viet. However, the Supreme Soviet had granted

Yeltsin emergency powers for the first twelve

months of the transition. As these powers neared

expiration, Yeltsin and the Supreme Soviet became

locked in a battle for control of Russia. As a com-

promise, Yeltsin replaced Gaidar with an old-school

industrialist, Viktor Chernomyrdin, but that did

not appease the Congress, which stripped Yeltsin

of his emergency powers on March 12. Narrowly

surviving an impeachment vote, Yeltsin threatened

emergency rule and called a referendum on his rule

for April 25, 1993. Yeltsin won that round, but the

battle between executive and legislature continued

all summer.

On September 21, 1993, Yeltsin issued decree

number 1400 dissolving the Supreme Soviet and

calling for elections to a new body in December.

Parliament, led by Khasbulatov and Rutskoi, re-

fused, and members barricaded themselves in the

YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

1707

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

White House. Rutskoi was sworn in as acting pres-

ident. Attempts at negotiation failed, and on Octo-

ber 3, the rebels seized the neighboring home of

Moscow’s mayor and set out to commandeer the

Ostankino television complex. Yeltsin then did

what the hardliners did not do in August 1991: He

ordered the White House be taken by force. Troops

stormed the building, more than one hundred peo-

ple died, and Khasbulatov, Rutskoi, and their col-

leagues were led to jail.

Parliamentary elections took place as scheduled

in December. Simultaneously, a referendum was

held to approve the super-presidential constitution

drafted by Yeltsin’s team. If the referendum failed,

Russians would have voted for an illegitimate leg-

islature. Fearing rivals for power, Yeltsin had elim-

inated the office of vice president in the new

constitution, but he also refused to create a presi-

dential political party. As a result, there was no ob-

vious pro-government party. Gaidar and his liberal

democrats lost to the ultra-nationalist Liberal De-

mocratic Party of Vladimir Zhirinovsky and the

Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF).

Rumors persist that turnout was below the re-

quired 50 percent threshold, which would have in-

validated the ratification of the constitution itself.

The Duma, the new bicameral parliament’s

lower house, began with a strong anti-Yeltsin

statement. In February it amnestied the participants

in the 1991 putsch and the 1993 Supreme Soviet

revolt. Yeltsin tried to accommodate the red-brown

coalition of Communists and nationalists in the

Duma. Economic liberalization eased, privatization

entered its second phase, and a handful of busi-

nessmen—the oligarchs—snatched up key enter-

prises at deep discount.

Yeltsin reached out to regions for support, with

mixed results. A series of bilateral treaties were

signed with the Russian republics, especially

Tatarstan, giving them greater autonomy than

specified in the federal constitution. However, one

republic, Chechnya, remained firm in its refusal to

recognize the authority of Moscow, and a show-

down became imminent. A group of hardliners

YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

1708

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian president Boris Yeltsin and Polish president Lech Walesa confer, August 25, 1993. © P

ETER

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

within the Yeltsin administration orchestrated an

invasion of Chechnya on December 11, 1994. Al-

though they had expected a quick victory, the

bloody war continued until August 1996.

Yeltsin approached presidential elections sched-

uled for June 1996 with four key problems. First

was the ongoing and highly unpopular war in

Chechnya. Second, the communists dominated the

1995 Duma elections. Third was his declining

health. (He had collapsed in October 1995, trigger-

ing a succession crisis in the Kremlin.) Fourth, his

approval ratings were in the single digits, and ad-

visors Oleg Soskovets and Alexander Korzhakov

urged him to cancel the election. But yet again,

Yeltsin launched an amazing political comeback. He

fired his most liberal Cabinet members, including

Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev whose pro-West

policies had angered many, and floated a new peace

plan for Chechnya.

In a campaign organized by Chubais and

Yeltsin’s daughter Tatiana Dyachenko, Yeltsin barn-

stormed across the country, delivering rousing

speeches, handing out lavish political favors, and

dancing with the crowds. The campaign was

bankrolled by the oligarchs—a group of seven en-

trepreneurs who had amassed tremendous wealth

in the privatization process under questionable cir-

cumstances and wanted to protect their interests.

The Kremlin boldly admitted to exceeding the cam-

paign-spending cap. Yeltsin failed to win a major-

ity of the votes in the election, forcing him into a

run-off with CPRF candidate Gennady Zyuganov.

Between the first election and the run-off,

Yeltsin suffered a massive heart attack. This news

was kept from the Russian population, who went

to the polls unaware of the situation. Only after

Yeltsin had secured victory was news of his health

released. He underwent quintuple bypass surgery

in November 1996, contracted pneumonia, and

was effectively an invalid for months. During this

time, access to the president and the daily business

of running the country fell to Yeltsin’s closest ad-

visors: Chubais and Dyachenko, known as “The

Family.”

Yeltsin’s last years in office were marked by a

declining economy, rising corruption, and frequent

turnover in the office of prime minister. The oli-

garchs soon turned on each other, fighting for as-

sets and access. Yeltsin’s immediate family was

implicated in a variety of graft schemes. With the

economy declining, Yeltsin embarked on prime min-

ister roulette. He fired Chernomyrdin, replacing

him with Sergei Kiriyenko (March–August 1998),

Chernomyrdin again (August 23–September 10),

then Yevgeny Primakov (September 10, 1998–May

12, 1999), and Sergei Stepashin (May 12–August

8). In August 1998 the ruble collapsed, and Russia

defaulted on its foreign loan obligations. Next in

line as prime minister came ex-KGB agent Vladimir

Putin.

In 1999 Yeltsin associates floated the idea of his

running for a third term. They argued that the

two-term limit imposed by the 1993 constitution

might not count Yeltsin’s 1991 election, as it oc-

curred under different political and legal circum-

stances. Yeltsin’s health was a key concern, as was

his family’s complicity in a growing number of

corruption schemes. Before Yeltsin could leave of-

fice he needed a suitable successor, one that could

protect him and his family. On New Year’s Eve,

1999, Yeltsin went on television to make a surprise

YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

1709

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian president Boris Yeltsin appeals to the people to vote in

the 1993 referendum. © P

ETER

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

announcement—his resignation. According to the

constitution, Prime Minister Putin would succeed

him, with elections called within three months. As

acting president, Putin’s first action was to grant

Yeltsin immunity from prosecution.

Yeltsin retired quietly to his dacha outside of

Moscow. Unlike Gorbachev, he did not form his

own think tank or join the international lecture cir-

cuit. Instead, Yeltsin wrote his third volume of

memoirs, Midnight Diaries, and largely kept out of

politics and public life.

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; CHECHNYA AND THE

CHECHENS; CHUBAIS, ANATOLY BORISOVICH; DY-

ACHENKO, TATIANA BORISOVNA; GAIDAR, YEGOR

TIMUROVICH; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH;

KHASBULATOV, RUSLAN IMRANOVICH; KORZHAKOV,

ALEXANDER VASILEVICH; OCTOBER 1993 EVENTS;

PUTIN, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH; RUTSKOI, ALEXAN-

DER VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Breslauer,George W. (2002). Gorbachev and Yeltsin As

Leaders. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dunlop, John B. (1993). The Rise of Russia and the Fall

of the Soviet Empire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

Shevtsova, Lilia. (1999). Yeltsin’s Russia: Myths and Re-

ality. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for Inter-

national Peace.

Yeltsin, Boris. (1990). Against the Grain. New York: Sum-

mit.

Yeltsin, Boris. (1994). The Struggle for Russia. New York:

Random House.

Yeltsin, Boris. (2000). Midnight Diaries. New York: Pub-

lic Affairs.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

YELTSIN CONSTITUTION See CONSTITUTION OF

1993.

YERMAK TIMOFEYEVICH

(d. 1585), Cossack chieftain, leader of an expedi-

tion that laid the basis for Russia’s annexation of

Siberia.

Little is known about Yermak’s early biogra-

phy, and many of the details of his Siberian cam-

paign are still disputed. Most sources indicate that

he was a Volga Cossack who fled north in 1581 in

order to escape punishment for piracy; Ruslan

Skrynnikov, however, argues that Yermak was

fighting in the Livonian War in 1581 and went to

Siberia in 1582. Yermak and his Cossack band were

hired by the Stroganovs, a family of wealthy Urals

merchants, to protect their possessions against at-

tacks by the Tatars and other indigenous peoples

of Siberia. Thereafter Yermak and his band of a

few hundred men set off along the Siberian rivers

in lightweight boats; it is not clear whether the

Stroganovs sent them to attack the Siberian

khanate, or whether the decision to go on to the

offensive was taken by the Cossacks. In October

1582 they defeated the Siberian khan, Kuchum, and

occupied his capital, Kashlyk (Isker). The local peo-

ples recognized Yermak’s authority and rendered

him tribute. In 1585, however, Khan Kuchum

launched a surprise attack on the Cossack camp

and killed most of the band. Yermak himself, ac-

cording to legend, drowned in the River Irtysh,

weighed down by a suit of armour that he had re-

ceived as a gift from the tsar. Subsequent expedi-

tions continued the Russian annexation of Siberia

that Yermak had pioneered. After his death Yermak

became a folk hero; his achievements were cele-

brated in oral tales and songs, and later depicted in

popular prints (lubki).

See also: IVAN IV; SIBERIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armstrong, Terence, ed. (1975). Yermak’s Campaign in

Siberia: A Selection of Documents, tr. Tatiana Minorsky

and David Wileman. London: Hakluyt Society.

Perrie, Maureen. (1997). “Outlawry (Vorovstvo) and Re-

demption through Service: Ermak and the Volga

Cossacks.” In Culture and Identity in Muscovy,

1359–1584, ed. A. M. Kleimola and G. D. Lenhoff.

Moscow: ITZ-Garant.

Skrynnikov, R. G. (1986). “Ermak’s Siberian Expedition.”

Russian History / Histoire Russe 13:1–39.

M

AUREEN

P

ERRIE

YESENIN, SERGEI ALEXANDROVICH

(1895–1925), popular poet of the Soviet period,

known for his evocations of the Russian country-

side and the Soviet demimonde.

YELTSIN CONSTITUTION

1710

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin (also spelled Es-

enin) born in 1895 in Konstantinovo, a farm vil-

lage in the Riazan province, where he attended

school. He came to prominence in Petrograd in

1915 as part of a group of “Peasant Poets.” His

early work was noted for its elegiac portrayal of

rural life and religious themes.

Yesenin was an ambivalent supporter of the

October Revolution and the Soviet state. He tried to

write on revolutionary themes, but his explo-

rations of intimate relationships, urban street life,

and the disappearance of old rural Russia were more

popular. Yesenin was also known for his charisma,

heavy drinking, and scandalous behavior. He was

married three times, once to the American dancer

Isadora Duncan. Yesenin committed suicide in De-

cember 1925, shortly after writing his final poem,

“Good-bye, My Friend, Good-bye,” in his own

blood.

Yesenin’s popularity continued after his death,

as readers were drawn to his unconventional

lifestyle and introspective poetry. This concerned

the Communist leadership, who believed that Yes-

enin had both reflected and encouraged a growing

sense of disaffection and “hooliganism” among So-

viet youth. Numerous attacks on “Yeseninism” ap-

peared in the Soviet press in 1926 and 1927. He

was also criticized by the so-called proletarian writ-

ers for his anti-urban bias and individualism. As a

result, official policy toward Yesenin’s works was

ambivalent, and no new editions of his work were

published between 1927 and 1948.

There was increased interest in Yesenin’s work

in the 1960s and 1970s. His influence was evident

on the rising generation of bard-singers, such as

Vladimir Vysotsky, and also on the emerging “Vil-

lage Prose” movement. One of Yesenin’s illegitimate

sons, Alexander Volpin-Yesenin, was an early dis-

sident and human rights advocate. Major collec-

tions of Esenin’s work include Radunitsa (1916),

The Hooligan’s Confession (1921), and Selected Works

(1922).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McVay, Gordon. (1976). Esenin: A Life. Ann Arbor, MI:

Ardis.

Slonim, Marc. (1977). Soviet Russian Literature: Writers

and Problems, 1917–1977, 2nd rev. ed. London and

New York: Oxford University Press.

B

RIAN

K

ASSOF

YEVTUSHENKO, YEVGENY

ALEXANDROVICH

(b. 1932), Russian poet, playwright, novelist, es-

sayist, photographer, film actor; member of Con-

gress of People’s Deputies, 1989–1991.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko was brought up in

Siberia by his mother; when she moved with him

to Moscow in 1944 she registered his date of birth

as 1933. He published his first poem in 1949 and

his first book in 1952. Yevtushenko studied at the

Union of Writers’ training school, the Gorky Lit-

erary Institute, Moscow, in the early 1950s. He

emerged after 1956 as one of the leading lights

of the Thaw under Nikita Khrushchev, in many

ways epitomizing its values and aspirations, and

has remained a public figure ever since. His per-

sonal lyrics expressed a new and liberating sense of

passionate individuality, and his poems on public

themes called for and declared a fresh commit-

ment to revolutionary idealism, in the spirit of

Mayakovsky. His attitudes were underpinned by a

frequently asserted commitment to the supremacy

of Russia as a fountainhead of positive human val-

ues, notwithstanding Russia’s own dark history

and the blandishments of Western civilization.

Yevtushenko declaimed his poetry in a histrionic

manner that has reminded some Americans of U.S.

fundamentalist preachers. In the early 1960s Yev-

tushenko became hugely popular in Russia, and his

recitals (often in the company of his then wife Bella

Akhmadulina, Andrei Voznesensky, and Bulat

Okudzhava) attracted large crowds to the stadiums

in which they were characteristically held. Yev-

tushenko’s national and international reputation was

established by two poems in particular, “Baby Yar”

(published September 1961) and “The Heirs of Stalin”

(published in Pravda, October 1962), which call re-

spectively for unrelenting vigilance against anti-

Semitism and the recurrence of Stalinism in Russia.

Yevtushenko soon began travelling abroad, a

proclivity that has eventually taken him by his

own count to ninety-five different countries. More

than any other aspect of his activities, his freedom

and frequency of travel led others to question the

fundamental nature of his relationship with the So-

viet authorities. His own protestations about how

he was continually censored, rebuked, and re-

stricted, and how he persistently used his position

to plead for others in more parlous situations, have

increasingly been interpreted as part and parcel of

his conniving in being used as a licensed dissident

YEVTUSHENKO, YEVGENY ALEXANDROVICH

1711

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

whose fundamental adherence to the Soviet system

and willingness to accommodate himself to it never

wavered. His outstanding poetic mastery has never

been in doubt, but beginning in the 1970s, the rise

of poets who rejected Yevtushenko’s flamboyant

style, public posturing, and acceptance of privilege

led to a growing view of him as a figure of the

hopelessly compromised past. Partly in response,

Yevtushenko branched out into other areas of cre-

ativity. During the later 1980s he demonstratively

led the way in publishing Russian poetry that had

been censored during the Soviet period. Since the

collapse of the USSR he has lived mainly in the

United States, regularly traveling back to Russia for

public appearances, and has continued to publish

prolifically in a variety of genres and argue his case

in media interviews.

See also: MAYAKOVSKY, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH;

OKUDZHAVA, BULAT SHALOVICH; THAW, THE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Yevtushenko, Yevgeny. (1991). The Collected Poems,

1952–1990, ed. Albert C. Todd. New York: Holt.

Yevtushenko, Yevgeny. (1995). Don’t Die Before You’re

Dead. New York: Random House.

G

ERALD

S

MITH

YEZHOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

(1895–1940), USSR State Security chief (1936–1938);

organizer of the Great Terror of 1937–1938.

Of humble origins and scant education, Niko-

lai Yezhov rose from tailor to industrial worker,

soldier, and Red Army and Communist Party func-

tionary. Since the early 1920s he was a provincial

party secretary in Krasnokokshaisk (Mari province),

Semipalatinsk, Orenburg, and Kzyl-Orda (Kazakh

republic). In 1927 he was transferred to Moscow

to become involved in personnel policy for the party

Central Committee and the USSR People’s Com-

missariat of Agriculture. In 1930 he was promoted

to chief of the Personnel Department of the Central

Committee. In 1934 he was included in the Central

Committee and appointed chief of the party Con-

trol Commission.

From 1935 on, as Secretary of the Central

Committee, he was in the top echelon of the party.

He was charged with supervising the USSR People’s

Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD), or state

security service, and its investigation of Leningrad

party chief Sergei Kirov’s murder, as well as with

organizing major purge operations in the party in

order to curb the party apparatus, which Josef

Stalin deemed too independent. From 1936 on he

organized major show trials against Stalin’s rivals

in the party. On September 25, 1936, Stalin ap-

pointed him People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs.

This was followed by a large purge operation in

the NKVD involving the liquidation of his prede-

cessor Genrikh Yagoda and his supporters, as well

as mass arrests within the party.

On July 30, 1937, by order of Stalin and the

Party Politburo, Yezhov issued NKVD Order 00447,

“Concerning the Operation Aimed at the Subjecting

to Repression of Former Kulaks, Criminals, and

Other Anti-Soviet Elements.” The operation was to

involve the arrest of almost 270,000 people, some

76,000 of whom were immediately to be shot.

Their cases were to be considered by “troikas,” or

bodies of the party chief, NKVD chief, and procu-

rator of each USSR province, who were given quo-

tas of arrests and executions. In return, the regional

authorities requested even higher quotas, with the

encouragement of the central leadership.

Another mass operation was directed against

foreigners living in the USSR, especially those be-

longing to the nationalities of neighboring coun-

tries (e.g., Poles, Germans, Finns). The Great Terror

was intended to liquidate elements thought insuf-

ficiently loyal, as well as alleged “spies.” All in all,

from August 1937 through November 1938, more

than 1.5 million people were arrested for counter-

revolutionary and other crimes against the state,

and nearly 700,000 of them were shot; the rest

were sent to Gulag concentration camps. By order

of Yezhov, and with Yezhov personally participat-

ing, the prisoners were tortured in order to make

them “confess” to crimes they had not committed;

the use of torture had the approval of Stalin and

the Politburo.

In April 1937, Yezhov was included in the lead-

ing five who in practice had taken over the leading

role from the Politburo, and in October of that same

year he was made a Politburo candidate member.

In April 1938, the leadership of the People’s Com-

missariat of Water Transportation was added to his

functions. But in fact, it was the beginning of his

decline. In August, Stalin appointed Lavrenty Beria

as his deputy and intended successor. After sharp

criticism, on November 23, 1938, Yezhov resigned

from his function as NKVD chief, though for the

time being he stayed on as People’s Commissar of

YEZHOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

1712

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Water Transportation. People close to him were ar-

rested, and under these conditions his wife, Yevge-

nia, committed suicide; Yezhov abandoned himself

to even more drinking than he was accustomed to.

On April 10, 1939, he was arrested. He could

not bear torture and during interrogation confessed

everything: spying, wrecking, conspiring, terror-

ism, and sodomy (apparently, he had maintained

frequent homosexual contacts). On February 2,

1940, he was tried behind closed doors and sen-

tenced to death, to be shot the following night.

His fall was given almost no publicity, and dur-

ing the ensuing months and years he was practi-

cally forgotten. Only since the 1990s have details

about his life, death, and activities become known.

In spite of this, during the de-Stalinization cam-

paign of the 1950s, he was brought up as nearly

the only person responsible for the terror; the term

Yezhovshchina, or the time of Yezhov, was brought

into use. Some historians of the Stalin period in-

deed tend to stress Yezhov’s personal contribution

to the terror, relating his dismissal to his over-

zealousness. As a matter of fact, Stalin suspected

him of disloyal conduct and of collecting evidence

against prominent party people, including even

Stalin himself. Others believe that he obediently ex-

ecuted Stalin’s instructions, and that Stalin dis-

missed him when he thought it expedient.

See also: GULAG; PURGES, THE GREAT; STALIN, JOSEF VIS-

SARIONOVICH; STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Conquest, Robert. (1990). The Great Terror: A Reassess-

ment. London: Hutchinson.

Getty, J. Arch, and Naumov, Oleg V. (1999). The Road

to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolshe-

viks, 1932–1939, tr. Benjamin Sher. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

Jansen, Marc, and Petrov, Nikita. (2002). Stalin’s Loyal

Executioner: People’s Commissar Nikolai Ezhov,

1895–1940. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Khlevnyuk, Oleg (1995). “The Objectives of the Great

Terror, 1937–1938.” In Soviet History, 1917–53: Es-

says in Honour of R.W. Davies, ed. Julian Cooper et

al. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Medvedev, Roy. (1989). Let History Judge: The Origins and

Consequences of Stalinism, rev. and expanded ed., tr.

George Shriver. New York: Columbia University

Press.

Starkov, Boris A. (1993). “Narkom Ezhov.” In Stalinist

Terror: New Perspectives, eds. J. Arch Getty and

Roberta T. Manning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

M

ARC

J

ANSEN

YUDENICH, NIKOLAI NIKOLAYEVICH

(1862–1933), general in the Imperial Russian

Army, hero of World War I, and anti-Bolshevik

leader.

Of noble birth, Nikolai Yudenich began his glit-

tering military career upon graduating, with first-

class marks, from the General Staff Academy in

1887. He served on the General Staff in Poland and

Turkestan until 1902, participated in the Russo-

Japanese War (earning a gold sword for bravery),

worked as deputy chief of staff from 1907, and

became chief of staff of Russian forces in the Cau-

casus in 1913. During World War I, Yudenich dis-

tinguished himself as Russia’s most consistently

successful general, inflicting numerous defeats

upon Turkey, notably at Sarikamish (December

1914) and, in August 1915, repulsing Enver Pasha’s

invasion in 1915, and in capturing Erzurum, Tre-

bizond, and Erzincan (February–July 1916). He

consequently figured prominently in Russian

wartime propaganda. With the overthrow of the

Romanovs in February 1917, Yudenich regained

overall command of the Caucasus Front. However,

dismayed by the revolution and reluctant to coop-

erate with the Provisional Government, he was re-

tired from active service in May. He returned to

Petrograd and lived underground for a year after

the October Revolution, before fleeing to Finland.

Thereafter he headed anti-Bolshevik forces in the

Baltic region, as commander-in-chief of the North-

west Army. Like other White leaders, Yudenich

failed to establish an effective political regime or

to attract sufficient support from the Allies, and

suffered strained relations with the non-Russian

peoples of his base territory. Nevertheless, he mas-

terminded the Whites’ advance to the outskirts of

Petrograd in the autumn of 1919. However, Trot-

sky pushed his forces back into Estonia, where they

were interned before being disbanded in 1920. Yu-

denich was briefly arrested by the Estonian gov-

ernment, but was allowed to settle into exile in

France. He largely shunned émigré politics until his

death, in Saint-Laurent-du-Var.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; WHITE ARMY; WORLD

WAR I

YUDENICH, NIKOLAI NIKOLAYEVICH

1713

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mawdsley, Evan. (2000). The Russian Civil War. Edin-

burgh: Birlinn.

J

ONATHAN

D. S

MELE

YUGOSLAVIA, RELATIONS WITH

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was

proclaimed on December 1, 1918, and was renamed

Yugoslavia on October 3, 1929 by Alexander Karad-

jordjevic. The creation of the new enlarged South

Slav state and the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia

together ruptured the once-strong bonds between

Russia and the South Slav lands, especially Serbia.

Russian support for Serbia in the summer of

1914 had helped precipitate World War I, which de-

stroyed the Romanov dynasty and eventually

brought the Bolsheviks to power. Like its neighbors,

the new Yugoslav state was fiercely anticommunist.

In 1920 and 1921 the kingdom joined Romania and

Czechoslovakia in a series of bilateral pacts that came

to be known as the Little Entente. The alliance was

primarily aimed at thwarting Hungarian irreden-

tism (one country’s claim to territories ruled or gov-

erned by others based on ethnic, cultural, or historic

ties), since the former kingdom of Hungary had lost

approximately 70 percent of its prewar territory.

The Little Entente also served as part of France’s east-

ern security system designed to contain both Ger-

many and Bolshevik Russia. Throughout the 1920s

and 1930s, relations between Moscow and Belgrade

were but a shadow of that which had preceded

World War I. Not only was Yugoslavia a supporter

of the postwar settlements that had aggrandized its

territory, but it also sought to isolate the Bolshevik

revolution; moreover, it had little trade with the new

Soviet state, in part because prewar relations be-

tween St. Petersburg and Belgrade had been based

almost entirely on diplomatic and cultural rather

than economic links. In addition, the rise of Nazi

Germany left much of Yugoslav trade within the

Third Reich’s orbit.

In 1941 Germany occupied Yugoslavia. Two

groups, the Chetniks, led by Dra a Mihailovic, and

the Partisans, under Josip Broz Tito, a Moscow-

trained communist, fought the Germans and at the

same time vied for supremacy within Yugoslavia.

Although Tito emerged victorious and Stalin’s

so-called Percentages Agreement with Winston

Churchill gave Moscow 50 percent influence in Yu-

goslavia, the Red Army had not occupied the coun-

try, and thus the Soviet Union was unable to

influence developments there as it could in other

areas of central and southeastern Europe. Tito’s

popularity and mass following stood in contrast to

the situation in the other countries of the future

“bloc,” where there were at best small native com-

munist parties dominated by the Soviet Union.

As a result, the communist state created in Yu-

goslavia in 1946 was independent of Soviet stew-

ardship even though its constitution was initially

modeled on the Soviet constitution. From the out-

set, Tito pursued an independent domestic policy

and an aggressive foreign one. His ambitions

threatened both Stalin’s leadership (by his promo-

tion of national communist movements) and also

peace in Europe (by such actions as the shooting

down of American planes during the Trieste Affair,

the Italian-Yugoslav border dispute, and his sup-

port for the communists in the Greek Civil War).

When Tito attempted to create a separate customs

YUGOSLAVIA, RELATIONS WITH

1714

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

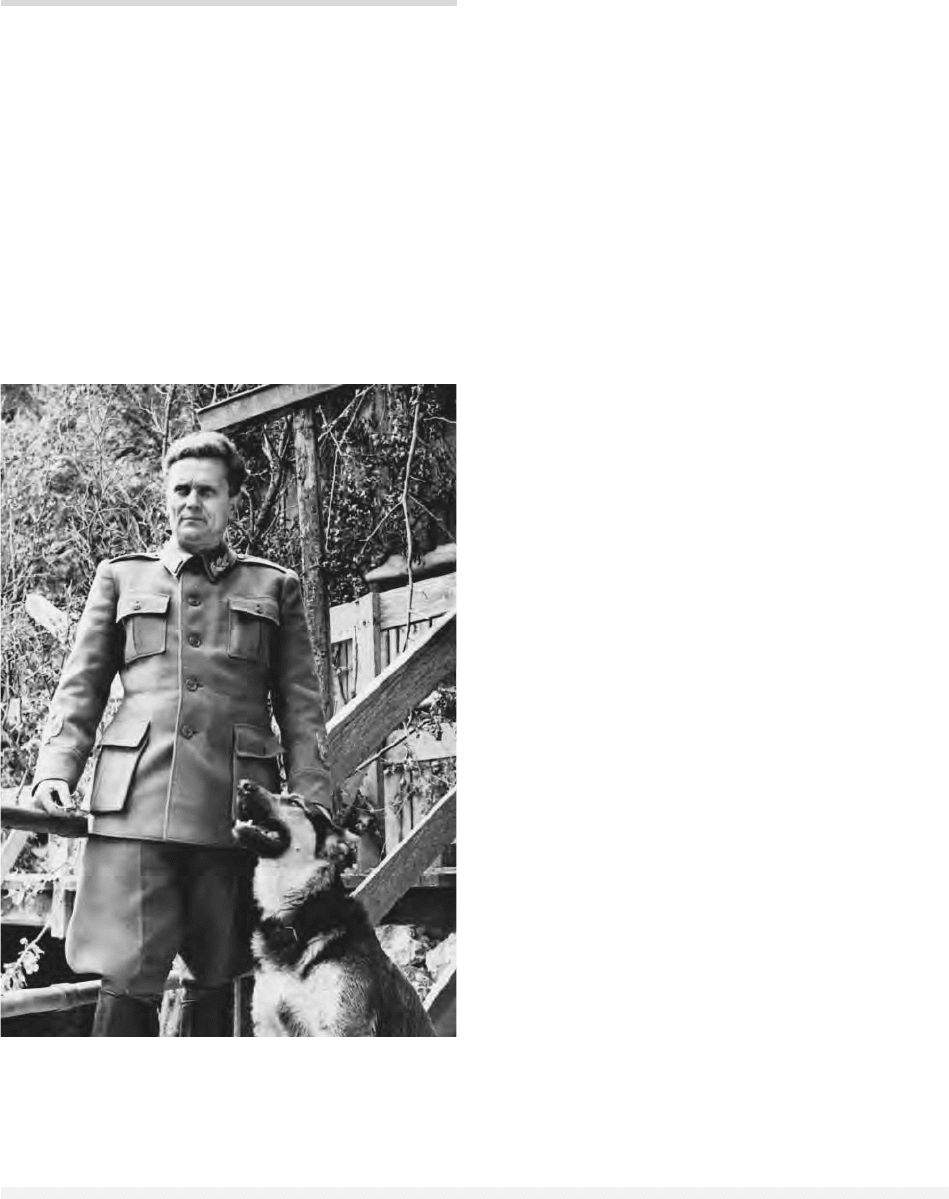

Marshal Josip Broz Tito defied Stalin and introduced his own

brand of communism in Yugoslavia. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

union with Bulgaria without consulting the Soviet

Union beforehand, and refused to abandon the ef-

fort as Stalin demanded, a break, usually referred

to as the Tito-Stalin split, quickly followed.

On June 28, 1948, the Cominform, the um-

brella communist propaganda organ directed by

Moscow, expelled Yugoslavia, charging Tito with

betraying the international communist movement.

Stalin hoped that this would force Yugoslavia to

submit to Soviet leadership, but he miscalculated.

Instead, Tito turned to a West that was all too will-

ing to forget his ideology and past actions and pro-

vide assistance to enable Yugoslavia to pursue

its own command economy and an independent

diplomatic and political stance that served as a

counterforce to the Soviet leader. Yugoslavia, for

example, supported the United Nations resolution

authorizing resistance to the invasion of South

Korea in June 1950. Tito soon became one of the

founders of the nonaligned movement, which held

its first conference in Belgrade in 1961.

Stalin’s death in 1953 opened the door for a par-

tial rapprochement with Belgrade. Issues such as

navigation and trade along the Danube River were

resolved, but the ideological rift never entirely healed.

In May 1955 Nikita Khrushchev visited Belgrade,

and the following year Tito visited to Moscow, and

the Cominform, which dissolved in April 1956, re-

nounced its earlier condemnations. Despite seem-

ingly cordial relations, however, the strains between

Moscow and Belgrade persisted, especially after the

Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, which saw the

independent-minded Hungarian revolt crushed, and

the arrest and subsequent murder of Imre Nagy, the

Hungarian prime minister, who had taken refuge in

the Yugoslav embassy in Budapest from 1956 un-

til 1958. In 1957 Tito angered Moscow by refusing

to sign a declaration commemorating the fortieth

anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution.

In the wake of the Sino-Soviet split of the early

1960s, another reconciliation took place, most no-

tably in the area of trade. However, Yugoslavia

continued to develop economic ties with western

Europe, as witnessed by the hundreds of thousands

of Yugoslavs who went west for employment as

well as by western investment in Yugoslavia. For

Belgrade, improved relations with Moscow were

but one part of a foreign policy that also looked to

the West (despite anti-American rhetoric), China

(after a reconciliation in the early 1970s), and the

Third World for influence and economic advan-

tages. Soviet leaders in turn realized that the ideo-

logical squabble with Belgrade served little purpose.

The death of Tito in 1980 began the fracturing

of a Yugoslav state strained by economic problems

and national resentments, and by 1990 the coun-

try fragmented. Similarly, the Soviet Union lost its

empire in eastern Europe in 1989, and by 1991 the

Soviet Union itself dissolved.

The break-up of the two states ironically

brought both of them full circle. During the nine-

teenth century, Russia had been the sole great

power supporter of Serbia. Although a “Yu-

goslavia” continued to exist after 1990, the name

denoted a rump state that comprised only Serbia

and Montenegro. As the wars in the former Yu-

goslavia raged, Moscow again served as Belgrade’s

principal benefactor, citing historical, religious, and

cultural ties. From military aid to peacekeeping in

the wake of Slobodan Milosevic’s failed attempt to

promote Serb authority through the brutal sup-

pression of the Albanian Kosovars, Russia had re-

gained an influence in Belgrade that it had not seen

since the early days of World War I.

See also: BALKAN WARS; COMMUNIST BLOC; COMMUNIST

INFORMATION BUREAU; MONTENEGRO, RELATIONS

WITH; SERBIA, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Djordjevic, Dimitrije. (1992). “The Yugoslav Phenome-

non.” In The Columbia History of Eastern Europe in the

Twentieth Century, ed. Joseph Held. New York: Co-

lumbia University Press.

Glenny, Misha. (2000). The Balkans: Nationalism, War,

and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. New York: Viking

Penguin.

Hupchick, Dennis P. (2002). The Balkans: From Constan-

tinople to Communism. New York: Palgrave.

Jelavich, Barbara. (1974). St. Petersburg and Moscow:

Tsarist and Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814–1974. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Rothschild, Joseph, and Wingfield, Nancy M. (2000). Re-

turn to Diversity: A Political History of East Central

Europe Since World War II. 3rd edition. New York:

Oxford University Press.

R

ICHARD

F

RUCHT

YURI DANILOVICH

(d. 1325), grand prince of Vladimir and the prince

of Moscow who initiated the rivalry for supremacy

between Moscow and Tver in northeastern Russia.

YURI DANILOVICH

1715

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY