Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WORKERS’ OPPOSITION

The Workers’ Opposition (Rabochaya oppozitsia)

was a group of trade union leaders and industrial

administrators within the Russian Communist

Party who opposed party leaders’ policy on work-

ers and industry from 1919 to 1921. The group

formed in the fall of 1919, when its leader, Alexan-

der Shlyapnikov, called for trade unions to assume

leadership of the highest party and state organs.

Leading members of the Metalworkers’ Union sup-

ported Shlyapnikov, who criticized the growing

bureaucratization of the Communist Party and So-

viet government, which he feared would stifle

worker initiative. The Workers’ Opposition advo-

cated management of the economy by a hierarchy

of elected worker assemblies, organized according

to branches of the economy (metalworking, tex-

tiles, mining, etc.).

Shlyapnikov, the chairman of the All-Russian

Metalworkers’ Union, was the most prominent

leader of the Workers’ Opposition. Thirty-eight in-

dividuals signed the theses of the Workers’ Oppo-

sition in December 1920. Most of them had been

metalworkers; they represented the Metalworkers’

Union, Miners’ Union, and the leading organs of

heavy industry. Alexandra Kollontai advised the

Workers’ Opposition and was a spokesperson for

it. She wrote a pamphlet about the group

(Rabochaya oppozitsia), which circulated among

delegates to the Tenth Communist Party Congress

in 1921.

Leaders of the Opposition used the resources

and organizations of major trade unions (metal-

workers, miners, textile workers) to mobilize sup-

port. Many meetings were arranged by personal

letter or word of mouth. Metalworkers or former

metalworkers composed the membership, all of

whom were also Communists.

The Workers’ Opposition drew attention to a

divide between Soviet industrial workers and the

Communist Party, which claimed to rule in the

name of the working class. Party leaders feared that

the Workers’ Opposition would inspire opponents

of the regime. At the Tenth Party Congress in

March 1921, the party banned the Workers’ Op-

position.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; KOLLONTAI, ALEXAN-

DRA MIKHAILOVNA; SHLYAPNIKOV, ALEXANDER GAV-

RILOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Holmes, Larry E. (1990). For the Revolution Redeemed: The

Workers Opposition in the Bolshevik Party, 1919–1921

(Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Stud-

ies, no. 802). Pittsburgh, PA : University of Pitts-

burgh Center for Russian and East European Studies.

Kollontai, Alexandra. (1971). The Workers Opposition in

Russia. London: Solidarity.

B

ARBARA

A

LLEN

WORKERS’ AND PEASANTS’ INSPECTORATE

See RABKRIN.

WORLD REVOLUTION

When Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels implored

workers of the world to unite, they announced a

new vision of international politics: world socialist

revolution. Although central to Marxist thought,

the importance of world revolution evoked little de-

bate until World War I. It was Vladimir Lenin who

revitalized it, made it central to Bolshevik political

theory, and provided an institutional base for it.

Although other Marxists, such as Nikolai Bukharin

and Rosa Luxemburg, devoted serious attention to

it, Lenin’s ideas had the most profound impact be-

cause they persuasively linked an analysis of im-

perialism with the struggle for world socialist

revolution.

In Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism

(1916), Lenin argued that modern war was due to

conflicts among imperialist powers and that any

revolution within the imperialist world would

weaken capitalism and hasten socialist revolution.

The contradictions of capitalism and imperialism

provided the soil that nourished world revolution.

In the fall of 1917, when Lenin cajoled his com-

rades to seize power, he argued that the Russian

Revolution was “one of the links in a chain of so-

cialist revolutions” in Europe. He believed in the im-

minence of such revolutions, which he deemed

essential to the Bolshevik revolution’s survival and

success. His optimism was not unfounded, as rev-

olutionary unrest engulfed Central and Eastern Eu-

rope in 1918–1920.

In 1919 Lenin helped to create the Communist

International (Comintern) to guide the world rev-

olution. As the revolutionary wave waned in the

1920s, Stalin claimed that world revolution was not

essential to the USSR’s survival. Rather, he argued,

WORLD REVOLUTION

1675

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

developing socialism in one country (the USSR) was

essential to keeping the world revolutionary move-

ment alive. Other Bolshevik leaders, notably Leon

Trotsky, disagreed, but in vain. Nonetheless, until

it adopted the Popular Front policy in 1935, the

Comintern pursued tactics for world revolution.

Unlike previous Comintern policies, which sought

to spark revolution, the Popular Front was a de-

fensive policy designed to stem the rise of fascism.

It marked the end of Soviet efforts to foment world

socialist revolution.

See also: LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McDermott, Kevin, and Agnew, Jeremy. (1997). The

Comintern: A History of International Communism from

Lenin to Stalin. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Nation, R. Craig. (1989). War on War: Lenin, the Zim-

merwald Left, and the Origins of Communist Interna-

tionalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

W

ILLIAM

J. C

HASE

WORLD WAR I

Imperial Russia entered World War I in the sum-

mer of 1914 along with allies England and France.

It remained at war with Germany, Austria, Hun-

gary, Italy, and Turkey until the war effort col-

lapsed during the revolutions of 1917.

In 1914 military theory taught that new tech-

nologies meant that future wars would be short,

decided by initial, offensive battles waged by mass

conscript armies on the frontiers. Trapped between

two enemies, Germany planned to defeat France in

the west before Russia, with its still sparse railway

net, could mobilize. Using French loans to build up

that net, Russia sought to speed up the process,

rapidly invade East Prussia, and so relieve pressure

on the French. Berlin therefore feared giving Rus-

sia a head start in mobilizing and, rightly or

wrongly, most statesmen accepted that if mobi-

lization began, war was inevitable.

On June 28, 1914, a nationalist Serbian stu-

dent shot Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the

Austro-Hungarian throne, at Sarajevo. To most

statesmen’s surprise, this provoked a crisis when

Austria, determined to punish the Serbs, issued an

unacceptable ultimatum on July 23. Over the next

six days, pressure mounted on Nicholas II but, rec-

ognizing that mobilization meant war, he refused

to order a general call-up that would force a Ger-

man response. Then Vienna declared war on Ser-

bia, Nicholas’s own efforts to negotiate with Kaiser

William II collapsed, and on July 30 he finally ap-

proved a general mobilization. When St. Petersburg

ignored Berlin’s demand for its cancellation within

twelve hours, Germany declared war on August 1.

Over the next three days Germany invaded Lux-

embourg, declared war on France on August 4, and

by entering Belgium, added Britain to its enemies.

THE WAR OF MOVEMENT:

SUMMER 1914–APRIL 1915

Some Social Democrats aside, Russia’s educated

public rallied in a Sacred Union behind their ruler.

Strikes and political debate ended, and on August

2, crowds in St. Petersburg cheered Nicholas II af-

ter he signed a declaration of war on Germany. Lo-

cal problems apart, the mobilization proceeded

apace as 3,115,000 reservists and 800,000 mili-

tiamen joined the 1,423,000-man army to provide

troops for Russian offensives into Austrian Galicia

and, as promised, France and East Prussia.

Although Nicholas II intended to command his

troops in person, he was pressured into appoint-

ing instead his uncle, Grand Duke Nikolai Niko-

layevich the Younger. Whatever its merits, this

decision split the front administratively from the

rear thanks to a new law that assigned the army

control of the front zone. This caused few prob-

lems when the battle line moved forward in 1914

and early 1915. However, without the tsar as a

civil-military lynchpin, it led to chaos during the

later Great Retreat.

The Grand Duke established his skeleton Stavka

(Supreme Commander-in-Chief’s General Head-

quarters) at Baranovichi to provide strategic direc-

tion to the Galician and East Prussian offensives.

These were to open on August 18-19 under the di-

rect supervision of the separate operational head-

quarters of the Northwest and Southwest Fronts.

Yet on August 6 Austria-Hungary declared war

and on the next day invaded Russian Poland. This

forestalled the Southwest Front (Third, Fourth,

Fifth, and Eighth Armies, with 52% of Russia’s

strength) and it opened its own Galician offensive

on August 18. Despite early enemy successes, the

Front’s armies trounced the Austrians and captured

the Galician capital of Lvov (Lemberg) on Septem-

ber 3. A week later the Russians won decisively at

Rava Ruska, and by September 12 they had foiled

an Austrian attempt to retake Lvov. By September

WORLD WAR I

1676

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

16 they had besieged the major fortress of Prze-

mysl and reached the San River. Resuming their of-

fensive, they then pushed another 100 miles to the

Carpathian passes into Hungary. Over seventeen

days the Austrians lost 100,000 dead, 220,000

wounded, 100,000 prisoners, and 216 guns, or

one-third of their effective strength.

The Northwest Front (First and Second Armies,

with 33% of Russia’s forces) was less successful.

Ordered forward to aid the desperate French on Au-

gust 13, Pavel Rennenkampf’s First Army advanced

slowly into East Prussia, was checked at Stallupo-

nen, then defeated the Germans at Gumbinnen on

August 20, and turned against Konigsberg. To the

south, Alexander Samsonov’s Second Army occu-

pied Neidenburg on August 22, and all East Prus-

sia seemed open to the Russians. But by August 23,

when the new German commander Paul von Hin-

denburg arrived with Erich von Ludendorff as chief

of staff, General Max von Hoffmann had imple-

mented plans to defeat the Russians piecemeal. Ac-

cordingly, on August 23–24 the Germans checked

Samsonov and, learning his deployments through

radio intercepts, withdrew to concentrate on Tan-

nenberg. When the Second Army again advanced

on August 26, it was trapped, virtually sur-

rounded, and then crushed. Samsonov shot him-

self, and by August 30 the Germans claimed more

than 100,000 prisoners.

This forced Rennenkampf’s withdrawal, and

during September 9–14, he too suffered defeat in

the First Battle of the Mansurian Lakes. Despite Ger-

man claims of a second Tannenberg and 125,000

prisoners, the First Army escaped and lost only

30,000 prisoners, as well as 70,000 dead and

wounded. The Germans then advanced to the

Niemen River before the front stabilized in mid-Sep-

tember. Again alerted by radio intercepts, they fore-

stalled a Russian thrust at Silesia by a spoiling

attack on September 30. Counterattacking in Gali-

cia, the Austrians then cleared the Carpathian ap-

proaches and relieved Przemysl before being halted

on the San in mid-October.

The Russians, repulsing a secondary attack in

the north, finally held the Germans before War-

saw. As the latter withdrew, devastating the coun-

tryside, the Russians again drove the Austrians

back to Kracow and reinvested Przemysl. This set

the pattern for months of seesaw fighting all along

the front. In the north, despite German use of poi-

son gas in January 1915, the Russian Tenth Army

withstood the bloody Winter Battles of Mansuria

and held firm until April. In the south, by Decem-

ber they again were deep into the Carpathians,

threatening Hungary, and holding positions 30

miles from Kracow. When relief efforts failed, Prze-

mysl finally fell (with 117,000 men) in March

1915, leaving the Russians free to force the

Carpathians.

Meanwhile, on October 29–30, 1914, two

German-Turkish cruisers had raided Russia’s Black

Sea coast. On declaring war, the tsar set up an au-

tonomous Caucasian Front in which the talented

chief of staff Nikolai Yudenich exercised real com-

mand. As he prepared the Caucasian Army to meet

a Turkish invasion, the Turkish Sultan-Khalifa’s

call for jihad (holy war) fueled pro-Turkish upris-

ings in the borderlands. Then on December 17 En-

ver Pasha launched his Third Army, still in summer

uniforms, on a crusade to recover lands ceded to

Russia in 1878. By December 25 the Russians were

fully engaged in the confused battles known as the

Sarykamysh Operation. In twelve days of bitter

winter combat Yudenich’s troops, despite heavy

losses, decisively crushed the Turks, and in Janu-

ary 1915 they invaded Ottoman Turkey.

During this period, the Russians held their own

against three enemies in two separate war zones

and showed that they had capable generals by rout-

ing two enemies and fighting a third, the Germans,

to a draw. For most, the heavy losses at Tannen-

berg and other locations were overshadowed by the

stunning victories elsewhere. Like other combat-

ants, Russia was slow to recognize that it faced a

long war, but it had avoided the trench warfare

that gripped the French front. Yet Grand Duke

Nikolai already had complained of shell shortages

in September 1914. The government responded by

reorganizing the Main Artillery Administration,

and a special chief assumed responsibility for com-

pletely guaranteeing the army’s needs for arms and

munitions by both state and private production. If

this promise was illusory, and other ad hoc agen-

cies proved equally ineffective, for the moment the

Russian command remained confident of victory.

THE GREAT RETREAT:

MAY–SEPTEMBER 1915

On May 2 the seesaw struggle in the East ended

when the Austro-Germans, after a four-hour “hur-

ricane of fire,” broke through the shallow Russian

trenches at Gorlice-Tarnow. This local success

quickly sparked the disastrous Great Retreat. As

the Galician armies fell back, a secondary German

strike in the north endangered the whole Russian

WORLD WAR I

1677

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

front. Hampered by increasing munitions shortages,

rumors of spies and treason, a panicked Stavka’s

ineffective leadership, administrative chaos, and

masses of fleeing refugees, the Russians soon lost

their earlier conquests. Despite Italy’s intervention

on the Allied side, Austro-German offensives con-

tinued unabated, and in midsummer the Russians

evacuated Warsaw to give up Russian Poland. Some

units could still fight, but their successes were lo-

cal, and overall, the tsar’s armies seemed over-

whelmed by the general disaster. The only bright

spot was the Caucasus, where Yudenich advanced

to aid the Armenians at Van and held his own

against the Turks.

The munitions shortages, both real and exag-

gerated, forced a full industrial mobilization that

by August was directed by a Special Conference for

Defense and subordinate conferences for transport,

fuel, provisioning, and refugees. Their creation ne-

cessitated the State Duma’s recall, which provided

a platform for the opposition deputies who united

as the Progressive Bloc. Seeking to control the con-

ferences, these Duma liberals renewed attacks on

the regime and demanded a Government of Public

WORLD WAR I

1678

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

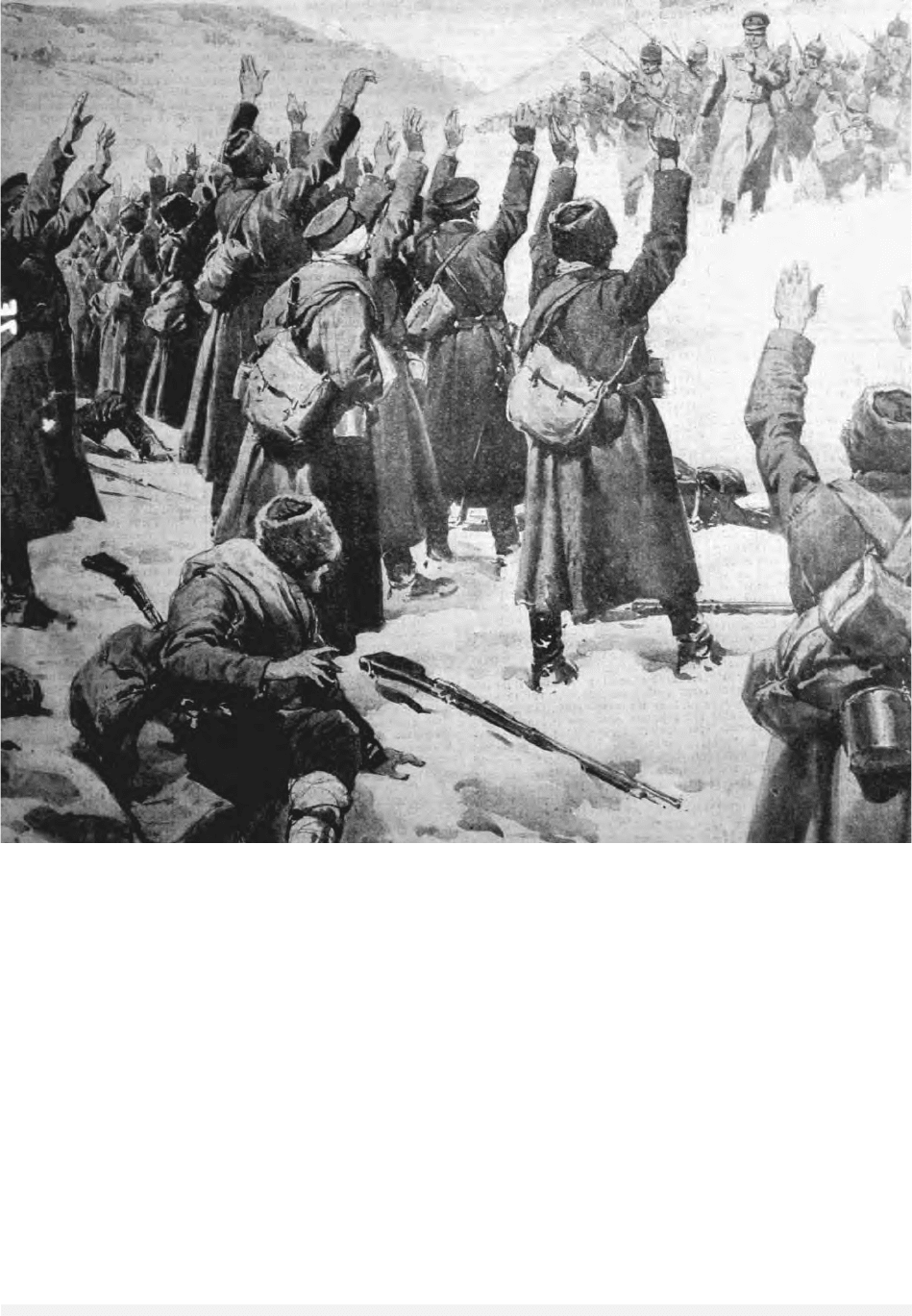

The Russian 10th Army, February 1915. Fighting in heavy snow, one Russian corps is defeated at Masuria while the others stood

firm until April. © SEF/A

RT

R

ESOURCE

, NY

Confidence (i.e., responsible to the Duma). Yet by

autumn Nicholas II had weathered the storm, as-

sumed the Supreme Command to reunite front and

rear, and prorogued the Duma. As the German of-

fensives petered out, the front stabilized, and a frus-

trated opposition regrouped. With the nonofficial

voluntary societies and new War Industries Com-

mittees, it now launched its campaign against the

Dark Forces whom it blamed for its recent defeats.

RUSSIA’S RECOVERY:

AUTUMN 1915–FEBRUARY 1917

In early December 1915, Stavka delegates met the

allies at Chantilly, near Paris, to coordinate their

1916 offensives. Allied doubts about Russian capa-

bilities were somewhat allayed by a local assault

on the Strypa River and operations in support of

Britain in Persia. Still more impressive was Yu-

denich’s renewed offensive in the Caucasus. He

opened a major operation in Armenia in January

1916, and on February 16 his men stormed the

strategic fortress of Erzurum. Retreating, the Turks

abandoned Mush, and by July, the Russians had

captured Erzingan. V. P. Lyakhov’s Coastal De-

tachment, supported by the Black Sea Fleet, also

advanced and on April 17–18, in a model combined-

arms operation, captured the main Turkish supply

port of Trebizond. In autumn 1916 the Russians

entered eastern Anatolia and Turkish resistance

seemed on the verge of collapse.

Assuming the mauled Russians would be inac-

tive in 1916, Germany opened the bloody battle for

Verdun on February 21. Yet increased supplies had

permitted a Russian recovery, and on March 18,

Stavka answered French appeals with a two-

pronged attack on German positions at Vish-

nevskoye and Lake Naroch, south of Dvinsk. Two

days of heavy shelling opened two weeks of mass

infantry assaults over ice, snow, and mud. The Ger-

mans held, and the Russians lost heavily but, what-

ever its impact on Verdun, this battle showed that

trench (or position) warfare had arrived in the East.

And like generals elsewhere, Russia’s seemed con-

vinced that only a single, concentrated infantry as-

sault, preceded by heavy bombardments, and

backed by cavalry to exploit a breakthrough, could

end the deadlock.

Some saw matters differently. One was Yu-

denich, who repeatedly smashed the Turks’ Ger-

man-built trench lines. Others included Alexei

Brusilov and his generals on the Southwest Front.

Like Yudenich, they devised new operational and

WORLD WAR I

1679

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian soldiers lie in wait ahead of their final assault on the Turkish stronghold Erzurum, April 1916. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

tactical methods that gained surprise by avoiding

massed reserves and cavalry, and by delivering a

number of simultaneous, carefully prepared in-

fantry assaults, at several points along an extended

front, with little or no artillery preparation. De-

spite Stavka’s doubts, Brusilov won permission to

attack in order to tie down the enemy forces in

Galicia. When Italy, pressed by Austria in the

Trentino, appealed for aid, Brusilov struck on June

4, eleven days before schedule. With no significant

artillery support, his troops achieved full surprise

on a 200-mile front, smashed the Austrian lines,

and advanced up to eighty miles in some sectors.

On June 8 they recaptured Lutsk before fighting

along the Strypa. Again the Germans rushed up re-

serves to save their disorganized ally and, after their

counterattack of June 16, the line stabilized along

that river. In the north, Stavka’s main attack then

opened before Baranovichi to coincide with Britain’s

Somme offensive of July 1. But it relied on the old

methods and collapsed a week later. The same was

true of Brusilov’s new attacks on Kovno, which

formally ended on August 13. Even so, heavy fight-

ing continued along the Stokhod until September.

Brusilov had lost some 500,000 men, but he

had cost the Austro-Germans 1.5 million in dead,

wounded, and prisoners, as well as 582 guns. Yet

his successes were quickly balanced by defeats

elsewhere. Russia had encouraged Romania to en-

ter the war on August 27 and invade Hungarian

Transylvania, after which Romania was crushed.

By January 1917 Romania had lost its capital, re-

treated to the Sereth River, and forced Stavka to

open a Romanian Front that extended its line 300

miles. This left the Russians spread more thinly and

the Central Powers in control of Romania’s impor-

tant wheat and oil regions.

Yet the Allied planners meeting at Chantilly on

November 15-16 were optimistic and argued that

simultaneous offensives, preceded by local attacks,

would bring victory in 1917. Stavka began imple-

menting these decisions by the Mitau Operation in

early January 1917. Without artillery support, the

Russians advanced in fog, achieved complete sur-

prise, seized the German trenches, and took 8,000

prisoners in five days. If a German counterstrike

soon recovered much of the lost ground, the Im-

perial Army’s last offensive shows that it had ab-

sorbed Brusilov’s methods and could defeat

Germans as well as Austrians.

By this date Russia had mobilized industrially

with the economy expanding, not collapsing, un-

der wartime pressures. Compared to 1914, by 1917

rifle production was up by 1,100 percent and shells

by 2,000 percent, and in October 1917 the Bolshe-

viks inherited shell reserves of 18 million. Similar

increases occurred in most other areas, while the

numbers of men called up in 1916 fell and, by De-

cember 31, had numbered only 3,048,000 (for a

total of 14,648,000 since August 1914). Yet their

quality had declined, war weariness and unrest

were rising, and, in late June 1916, the mobilization

for rear work of some 400,000 earlier exempted

Muslim tribesmen in Turkestan provoked a major

rebellion. By 1917 a harsh winter, military demands,

and rapid wartime industrial expansion had com-

bined to overload the transport system, which ex-

acerbated the tensions brought by inflation, urban

overcrowding, and food, fuel, and other shortages.

Despite recent military and industrial successes,

Russia’s nonofficial public was surprisingly pes-

simistic. If war-weariness was natural, this mood

also reflected the political opposition’s propaganda.

Determined to gain control of the ministry, the lib-

erals rejected all of Nicholas II’s efforts at accom-

modation. As rumors of treason and a separate

peace proliferated, the opposition dubbed each new

minister a candidate of the dark forces and crea-

ture of the hated Empress and Rasputin, whose

own claims gave credence to the rumors. This “as-

sault on the autocracy,” as George Katkov describes

it, gathered momentum when the Duma reopened

on November 14. Liberal leader Paul Milyukov’s

rhetorical charges of stupidity or treason were

seconded by two right-wing nationalists and long-

time government supporters. The authorities banned

these seditious speeches’ publication, but the oppo-

sition illegally spread them throughout the army,

and some even tried to suborn the high command.

The clamor continued until the Duma adjourned

for Christmas on December 30, when a group of

monarchists murdered Rasputin to save the regime.

Yet the liberal public remained unmoved and its

press warned that “the dark forces remain as they

were.”

REVOLUTION AND COLLAPSE:

FEBRUARY 1917–FEBRUARY 1918

Russia therefore entered 1917 as a house divided,

the dangers of which became evident as a new

round of winter shortages, sporadic urban strikes

and food riots, and military mutinies set the stage

for trouble. On February 27 the Duma reconvened

with renewed calls for the removal of “incompe-

tent” ministers, and 80,000 Petrograd workers

went on strike. But the tsar, having hosted an In-

WORLD WAR I

1680

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ter-Allied Conference in Petrograd, returned to

Stavka confident that his officials could cope.

Events now moved rapidly. On March 8, po-

lice clashed with demonstrators protesting food

shortages on International Women’s Day. Over the

next two days protests spread, antiwar slogans ap-

peared, strikes shut down the city, the Cossacks re-

fused to fire upon protestors, and the strikers set

up the Petrograd Soviet (Council). When Nicholas

II ordered the garrison to restore order, its aged re-

servists at first obeyed. But on March 12 they mu-

tinied and joined the rebels. The tsar’s ministers

were helpless before two new emergent authorities:

a Provisional Committee of the State Duma (the

prorogued Duma meeting unofficially) and the Pet-

rograd Soviet.

This list now included soldier deputies, and on

March 14 the Petrograd Soviet issued its famous

Order No. 1. This extended its power through the

soldiers’ committees elected in every unit in the gar-

rison, and in time in the whole army. For the mo-

ment, the Soviet supported a newly formed

Provisional Government headed by Prince Georgy

Lvov. When Nicholas tried to return to personally

restore order, his train was diverted to the North-

west Front’s headquarters in Pskov. There he ac-

cepted his generals’ advice and on March 15

abdicated for himself and his son. His brother,

Grand Duke Mikhail, followed suit, the Romanov

dynasty ended, and the Imperial Army became that

of a de facto Russian republic.

At first both the new government and soviets

supported the war effort, and the army’s command

structure remained intact. Plans for the spring of-

fensive continued, although the changing political

situation forced its delay. By April antiwar agita-

tion was rising, discipline weakening, and Stavka

was demanding an immediate offensive to restore

WORLD WAR I

1681

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

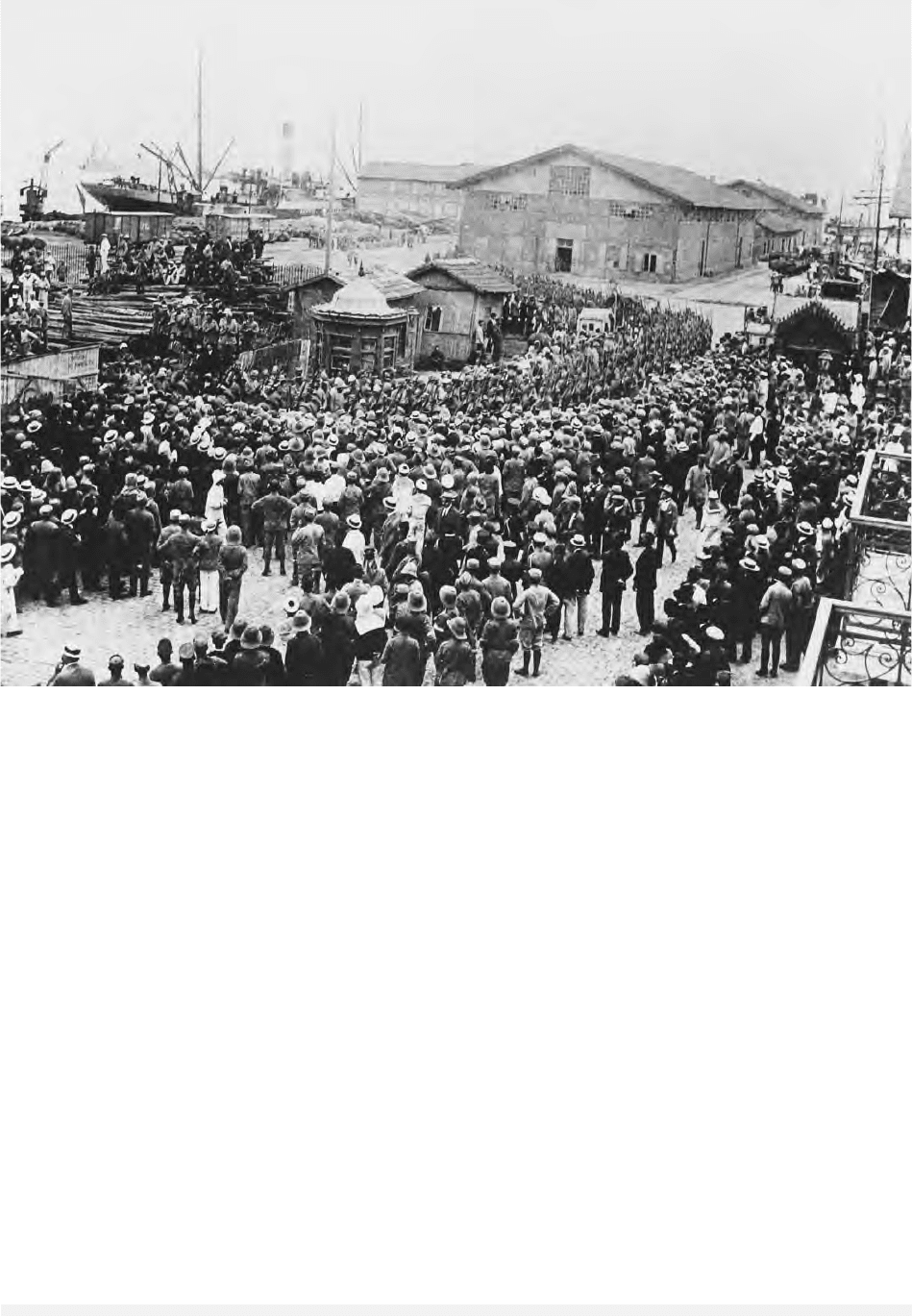

Russian troops land at Salonika, Greece, to fight Bulgarian forces. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

the army’s fighting spirit. Hopes for success rose

when Brusilov was named commander-in-chief,

and a charismatic radical lawyer, Alexander Keren-

sky, War and Naval Minister. Finally, on July 1,

the Southwest Front’s four armies, using Brusilov’s

tactics, opened Russia’s last offensive. Initially suc-

cessful, it collapsed after only three days, and the

Russians again retreated. In two weeks they lost

most of Galicia and more than 58,000 officers and

men, while a pro-Bolshevik uprising in the capital

(the July Days) threatened the government.

Kerensky survived the crisis to become premier,

while Lavr Kornilov, who advocated harsh mea-

sures to restore order, replaced Brusilov. The Bol-

shevik leaders were now imprisoned, underground,

or in exile in Finland, but their antiwar message

won further soldier-converts on all fronts. The Ger-

mans tested their own Brusilov-like tactics by cap-

turing Riga during September 1–6, but otherwise

remained passive as the revolutionary virus did its

work. Riga’s fall revealed Russia’s inability to fight

even defensively and helped provoke the much-

debated Kornilov Affair. When Stavka ordered units

to disperse the Petrograd Soviet, Kerensky (what-

ever his initial intentions) branded Kornilov a

traitor and used the left to foil this Bonapartist

adventure.

Bolshevik influence now made the officers’

position impossible. Desertion was massive, and

units on all fronts dissolved. After Vladimir Lenin

and Leon Trotsky took power on November 7, the

army became so disorganized that a party of

Baltic sailors easily seized Stavka and murdered

General Nikolai Dukhonin, the last real com-

mander-in-chief. The army no longer existed as

an effective fighting force and, with peace talks

underway at Brest-Litovsk, the so-called demobi-

lization congress of December sanctioned the

harsh reality. In February 1918 the army’s rem-

nants mounted only token resistance when the

Austro-Germans attacked and, despite desperate

attempts to create a Workers’ and Peasants’ Red

Army, forced the Soviet government to accept the

diktat (dictated or imposed peace) of Brest-Litovsk

on March 3.

CONCLUSION

Western accounts of Russia’s war are dominated

by the Tannenberg defeat of 1914, the Great Re-

treat of 1915, and the debacle of 1917. Yet the Im-

perial Army’s record compares favorably with

those of its allies and its German opponent, and

surpassed those of Italy, Austria-Hungary, and

Turkey. Despite many real problems, the same is

true of efforts to organize the war economy. But

the regime’s failures were exaggerated, and its suc-

cesses often obscured, by a domestic political strug-

gle that undercut the war effort and helped bring

the final collapse.

See also: BREST-LITOVSK PEACE; JULY DAYS OF 1917;

KERENSKY, ALEXANDER FYODOROVICH, KORNILOV AF-

FAIR; NICHOLAS II; STAVKA; TANNENBERG, BATTLE OF;

YUDENICH, NIKOLAI NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, W. E. D., and Muratoff, Paul. (1953). Caucasian

Battlefields: A History of the Wars on the Turco-Cau-

casian Border, 1828–1921. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Brusilov, Aleksei A. (1930). A Soldier’s Note-Book,

1914–1918. London: Macmillan.

Florinsky, Michael T. (1931). The End of the Russian Em-

pire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gatrell, Peter. (1986). The Tsarist Economy, 1850–1917.

London: Batsford.

Golder, Frank A. [1927] (1964). Documents of Russian His-

tory, 1914–1917. New York: Appleton-Century;

reprint, Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

Golovin, Nicholas N. (1931). The Russian Army in the

World War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Heenan, Louise Erwin. (1987). Russian Democracy’s Fatal

Blunder: The Summer Offensive of 1917. New York.

Praeger.

Jones, David R. (1988). “Imperial Russia’s Forces at

War.” In Military Effectiveness, 3 vols., ed. A. R. Mil-

let and W. Murray. London: Allen and Unwin.

Jones, David R. (2002). “The Imperial Army in World

War I, 1914–1917.” In The Military History of Tsarist

Russia, ed. F.W. Hagan and R. Higham. New York:

Palgrave.

Katkov, George. (1967). Russia 1917: The February Revo-

lution. London: Longmans.

Kerensky, Alexander F. (1967). Russia and History’s Turn-

ing Point. New York: Duell, Sloane and Pearce.

Knox, Alfred W. F. (1921). With the Russian Army,

1914–1917, 2 vols. London: Hutchinson.

Lincoln, Bruce W. (1986). Passage Through Armageddon:

The Russians in War and Revolution, 1914–1918. New

York: Simon and Schuster.

Pares, Bernard. (1939). The Fall of the Russian Monarchy.

New York: Knopf.

Showalter, Dennis E. (1991). Tannenberg: Clash of Em-

pires. Hamden, CT: Archon.

WORLD WAR I

1682

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Siegelbaum, Lewis H. (1983). The Politics of Industrial Mo-

bilization in Russia, 1914–17: A Study of the War In-

dustries Committees. London: Macmillan.

Stone, Norman. (1975). The Eastern Front, 1914–1917.

New York: Scribner’s Sons.

Wildman, Allan K. (1980, 1987). The End of the Russian

Imperial Army, 2 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

D

AVID

R. J

ONES

WORLD WAR II

World War II began in the Far East where Japan,

having invaded China in 1931, became involved in

full-scale hostilities in 1937. In Europe the German

invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, brought

Britain and France into the war two days later. Italy

declared war on Britain on June 10, 1940, shortly

before the French surrender on June 21. Having de-

feated France but not Britain, Germany attacked the

Soviet Union a year later on June 22, 1941. Then

the Japanese attacked United States naval forces in

Hawaii on December 7, 1941, and British colonies

in Hong Kong and Malaya the following day. The

subsequent German and Italian declarations of war

on the United States completed the lineup: Ger-

many, Italy, and Japan, the Axis powers of the

Anti-Comintern Treaty of 1936, against the Allies:

the United States of America, the British Empire

and Dominions, and the Soviet Union. Only the So-

viet Union and Japan remained at peace with each

other until the Soviet declaration of war on August

8, 1945, two days after the atomic bombing of Hi-

roshima.

The pattern of the war resembled a tidal flow.

Until the end of 1942 the armies and navies of the

Axis continually extended their power through Eu-

rope, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Toward the end

of 1942 the tide turned. The Allies won decisive vic-

tories in each theater: the Americans over the

Japanese fleet at Midway and over the Japanese

army on the island of Guadalcanal; the British over

the German army in North Africa at el Alamein;

and the Soviet army over the German army at Stal-

ingrad. From 1943 onward the tide reversed, and

the powers of the Axis shrank continually. Italy

surrendered to an Anglo-American invasion on Sep-

tember 3, 1943; Germany to the Anglo-American

forces on May 7, 1945, and to the Red Army the

following day; and Japan to the Americans on Sep-

tember 7, 1945. The war was over.

EVENTS LEADING TO THE WAR

Why did the Soviet Union become entangled in this

war? German preparations for an invasion of the

Soviet Union began in 1940, following the French

surrender, for three reasons. First, the German

leader Adolf Hitler believed that the presence of the

Red Army to his rear was the main reason that

Britain, isolated since the fall of France, had not

come to terms. He expected that a knockout blow

in the east would finish the war in the west. Sec-

ond, if the war in the west continued, Hitler be-

lieved that Britain would use its naval superiority

to blockade Germany; he planned to ensure Ger-

many’s food and oil supplies by means of overland

expansion to the east. Third, Hitler had become en-

tangled in the west only because of his aggression

against Poland, but Poland was also a means to an

end: a gateway to Ukraine and Russia where he

sought Germany’s “living space.” Thus an imme-

diate attack on the Soviet Union promised to over-

come all the obstacles barring his way in foreign

affairs.

At the same time the Soviet Union was not a

passive victim of the war. Soviet preparations for

a coming war began in the 1920s. They were

stepped up following the war scare of 1927, which

strengthened Josef Stalin’s determination to accel-

erate military and industrial modernization. At this

stage Soviet leaders understood that an immediate

war was unlikely. They did not fear Germany—

which was still a democracy and a relatively

friendly power—but Poland, Finland, France, or

Japan. They feared for the relatively distant future,

and this is one reason why Soviet rearmament, al-

though determined, was slow at first; they under-

stood that the first task was to build a Soviet

industrial base.

In the early 1930s Stalin became sharply aware

of new real threats from Japan under military rule

in the Far East and from Germany under the Nazis

in the west. In the years that followed he gave

growing economic priority to the needs of external

security. However, for much of the decade Stalin

was much more concerned with domestic threats;

he believed his external opponents to be working

against him by plotting secretly with his internal

enemies rather than openly by conventional mili-

tary and diplomatic means. In 1937–1938 he di-

rected a savage purge of the Red Army general staff

and officer corps that gravely weakened the armed

forces in which he was simultaneously investing

billions of rubles. The same purges damaged his

own credibility on the world stage; as a result those

WORLD WAR II

1683

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

countries with which he shared common interests

became less likely to see him as a worthy ally, and

his external enemies became more likely to attack

him. Stalin therefore approached World War II with

several deadly enemies, few friends in foreign cap-

itals, and an army that was growing and well

equipped but morally broken.

Conflict between the Soviet Union and Japan

was different from conflict with Germany. Japan

first: From their base in north China in May 1939,

the Japanese armed forces began a series of prob-

ing border attacks on the Soviet Union that cul-

minated in August with fierce fighting and a

decisive victory for the Red Army at Khalkin-Gol

(Nomonhan). After that, deterred from encroach-

ing further on Soviet territory, the Japanese shifted

their attention to the softer targets represented by

British and Dutch colonial possessions in southeast

Asia. In April 1941 the USSR and Japan concluded

a treaty of neutrality that lasted until August 1945;

WORLD WAR II

1684

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

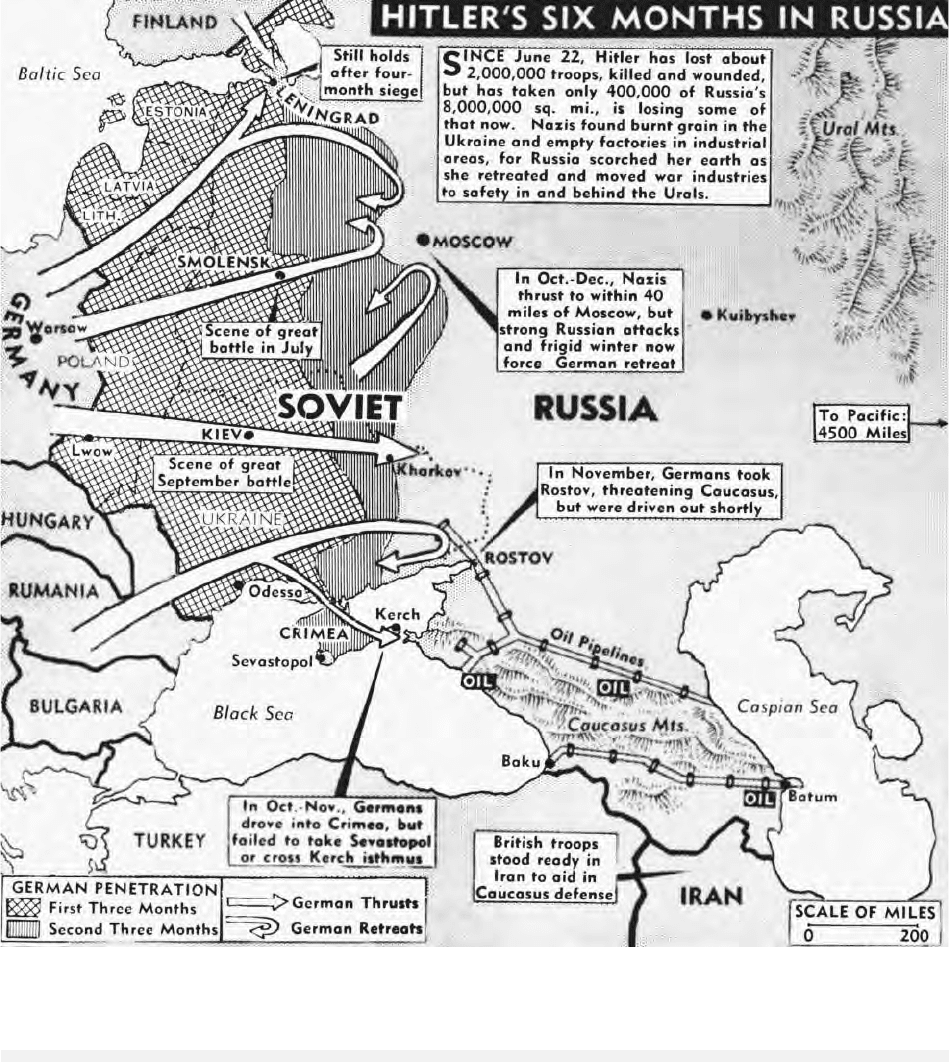

Map shows Operation Barbarossa and subsequent Nazi advances into the USSR, late 1941. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS