Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

378 5 TEM Applications of EELS

insulating gap would form a weak-link structure. Unfortunately, fully oxygenated

YBCO appears to retain its oxygen content even after high electron dose, although

an electron beam has been used to cut nanometer-wide channels in an amorphous

phase of similar composition (Humphreys et al., 1988; Devenish et al., 1989).

MgB

2

was discovered in 2001 to be superconducting below 39 K. Oxygen doping

not only provides flux-pinning centers in the form of nano-precipitates inside the

MgB

2

grains, but also leads to MgO or BO

x

precipitates at the grain boundaries.

By recording spectra for different crystal orientations and collection angles, Klie

et al. (2003) showed that a prepeak at the boron K-edge largely represents the p

xy

states that are believed to play an important role in superconductivity. There is also

interest in iron-pnictide materials as high-T

c

superconductors and in the case of

NdFeAsO, Idrobo et al. (2010) report that the Fe L

3

/L

2

and Nd M

5

/M

4

ratios vary

with crystallographic orientation and specimen temperature, these changes being

correlated with changes in electronic structure.

5.7.3 Carbon-Based Materials

Carbon is a uniquely important element and of practical interest as a result of the

development of hard diamond-like coatings and the discovery of fullerenes (C

60

,

etc.) in 1985, carbon nanotubes in 1991, and more recently single-layer graphene

and its derivatives.

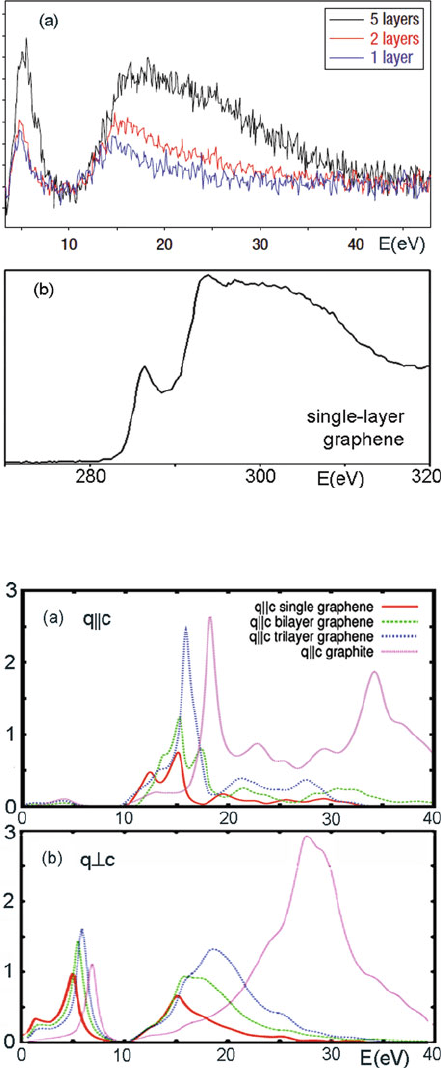

Graphene has low-loss and core-loss spectra as shown in Fig. 5.60. When the

thickness of a graphite specimen is reduced, the bulk plasmon (7 and 27 eV) peaks

eventually become redshifted, to about 5 and 14.5 eV in the case of a single graphene

layer. These shifts are in substantial agreement with calculations made using local

density functional code (Eberlein et al., 2008). They might also be seen as a change

from bulk to surface plasmons, bearing i n mind that the two surface modes are

highly coupled and that dispersion makes the peak q-dependent (Section 3.3.5).

Calculated energy-loss functions for graphene and graphite are shown in Fig. 5.61.

The out-of-plane (q||c) mode approaches zero in single-layer graphene, whose

π-plasmon exhibits a linear dispersion, from 5.1 eV at q = 1nm

–1

to 6.7 eV at q =

4nm

−1

(Lu et al., 2009). Linear dispersion is also observed for two-layer material

but is closer to quadratic for three layers. Single-layer material can be distinguished

form the fact that its electron diffraction pattern has no higher order Laue zones and

varies little with specimen orientation (Wu et al., 2010). Graphene becomes dam-

aged as a result of knock-on processes at incident electron energies above about

60 keV.

Carbon nanotubes are rolled-up graphene sheets capped with fullerene-like

end structures and exist in single-wall (SWCNT) and multiwall (MWCNT) form.

They display nondispersive excitations, whose energies are related to the elec-

tronic density of states and dispersive excitations related to a collective excitation

of the π-electrons polarized along the nanotube axis. Despite the small dimen-

sions, dielectric theory appears to apply approximately; the dielectric function has

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 379

Fig. 5.60 (a)Low-loss

spectra of single-, double-,

and five-layer unsupported

graphene, recorded using

100-keV electrons (Gass

et al., 2008). (b) Carbon

K-edge recorded using

200-keV electrons from

single-layer freestanding

graphene. The K-edge of a

double layer appeared similar.

From Dato et al. (2008)

Fig. 5.61 Energy-loss

function calculated for a

single layer and multilayers

of graphene with q||c (top)

and q⊥c (bottom).The x-axis

represents energy loss in eV

and the y-axis is in arbitrary

units. From Bangert et al.

(2008), copyright © 2009

WILEY-VCH Verlag

GmbH & Co. KGaA,

Weinheim

380 5 TEM Applications of EELS

been calculated from Kramers–Kronig analysis of EELS data (Pichler et al., 1998).

The SWCNT π-resonance energy (15 eV) is close to that of single-layer graphene

and shows linear dispersion, whereas interband transitions below 4 eV show no

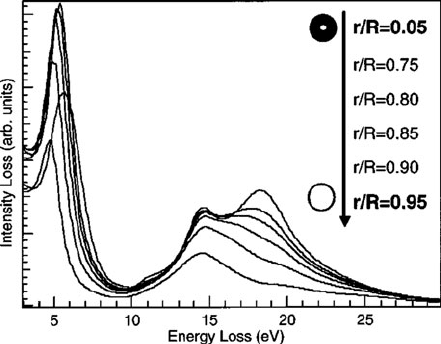

dispersion (Pichler et al., 1998). As the wall thickness increases, the dielectric prop-

erties become closer to those of graphite (Stöckli et al., 1997). A MWCNT peak

at 19 eV has been identified as a radial surface plasmon mode (Stephan et al.,

2002). Especially for larger diameter tubes, the plasmon energy depends more on

the number of graphene layers than on the overall diameter (Upton et al., 2009); see

Fig. 5.62. EELS fine structure below 5 eV shows agreement with optical data and

DOS calculations (Sato et al., 2008b). Zobelli et al. (2007) have shown that carbon

and boron nitride nanotubes become damaged by a knock-on mechanism at incident

electron energies above 80 keV. Nanotube bundles have also been investigated by

EELS (Reed and Sarikaya, 2001).

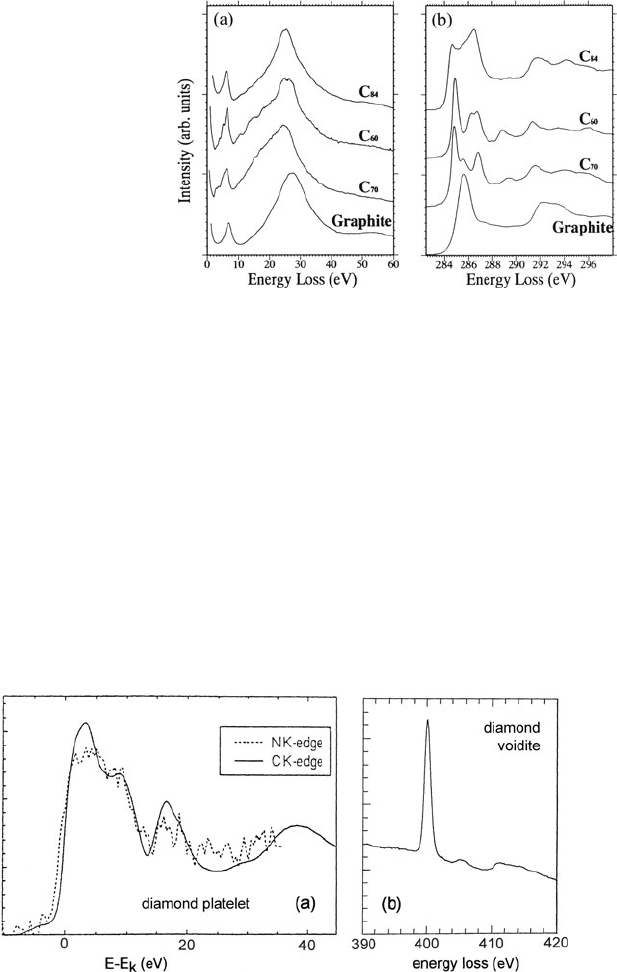

Fullerenes were discovered in soot condensed from carbon vapor and found to

be molecules comprised of graphite-like sheets bent into spherical or ellipsoidal

shapes. The solid form (fullerite) can be extracted with benzene or by subliming

the deposit onto a substrate to create a thin film. The energy-loss spectrum of C

60

fullerite shows a main (σ +π) plasmon peak at 25.5 eV, a π-resonance peak at

6.4 eV, and several subsidiary peaks (Hansen et al., 1991; Kuzuo et al., 1991). The

peaks of other fullerites, such as C

70

,C

76

, and C

84

, are shifted in energy and their

fine structure is different (Terauchi et al., 1994; Kuzuo et al., 1994). The carbon

K-edge structures are also distinguishable and unlike that of graphite (Fig. 5.63),

so EELS is useful for identifying small volumes of these materials. Fullerenes are

damaged by electron doses above about 100 C/cm

2

, apparently by radiolysis rather

than knock-on displacement (Egerton and Takeuchi, 1999). They can be polymer-

ized, for example, with UV light, creating materials with a smaller bandgap and a

reduced K-edge π

∗

peak (Terauchi et al., 2005). Anisotropic dielectric theory has

Fig. 5.62 Low-loss spectra

of carbon nanotubes,

calculated from dielectric

theory for external radius R =

20 nm and six values of

internal radius r, from 1 to

19 nm. From Stephan et al.

(2002), copyright American

Physical Society. http://link.

aps.org/abstract/PRB/v66/

p155422

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 381

Fig. 5.63 (a) Low-loss and

(b) K-loss spectra of

fullerites, compared with

graphite. From Kuzuo et al.

(1994), copyright American

Physical Society. http://link.

aps.org/abstract/PRB/v49/

p5054

been developed (Stöckli et al., 1998) to describe plasmon excitation in multiwalled

carbon spheres (carbon onions).

Diamond combines high hardness, thermal conductivity, and refractive index

(2.4) with very low electrical conductivity and transparency to visible light. Natural

diamond is classified on the basis of infrared spectra: unlike their type II cousins,

type I diamonds contain an appreciable amount of nitrogen, either segregated

(type Ia) or dispersed (type Ib). In the former case, TEM reveals the presence of

10–100 nm platelets lying on {100} planes, while EELS measurements (Bruley,

1992; Fallon et al., 1995) have shown that the nitrogen content of the platelets can

vary between 0.08 and 0.47 monolayer. The nitrogen and carbon K-edge ELNES

were similar, suggesting that N and C atoms have the s ame local environment

and that N atoms are present as isolated substitutional impurities; see Fig. 5.64a.

Fig. 5.64 (a) Nitrogen K-edge recorded at a platelet, scaled to match the carbon K-edge from

nearby diamond. The shapes are basically similar but the K-edge appears to have higher intensity

within 20–30 eV of the threshold (Fallon et al., 1995). (b) Nitrogen K-edge recorded from a region

of diamond containing a voidite. From Luyten et al. ( 1994 ). Copyright Taylor and Francis

382 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Additional scattering around 5 eV at the platelets has been interpreted in terms of

localized states arising from partial dislocations (Bursill et al., 1981).

A small rise in intensity occurring about 5 eV before the carbon K-edge (e.g.,

Fig. 5.37) is more prominent in thin specimens and may be associated with surface

states within the bandgap or π

∗

levels of a graphitic surface layer. Using spatial-

difference EELS, Bruley and Batson (1989) detected additional intensity in the

pre-edge region when the electron beam was placed close to a dislocation, perhaps

indicating excitation to defect or impurity states. The presence of a monolayer of

oxygen at the {111} free surface of diamond has been deduced from the observa-

tion of an oxygen K-edge in reflection mode energy-loss spectra (Wang and Bentley,

1992).

Some natural diamonds contain octahedral-faceted inclusions, a few nanometers

in size, known as voidites. Bruley and Brown (1989) showed that some voidites

contain nitrogen, a sharp peak at the ionization threshold indicating N

2

rather than

NH

3

(previously proposed). The nitrogen concentration appeared to be independent

of voidite size, its average value being about half the carbon concentration in dia-

mond. Despite the high pressure involved, the nitrogen did not appear to be metallic,

as evidenced by the lack of additional intensity below 5 eV. No diffraction spots

were observed, suggesting that nitrogen is present in an amorphous phase. Luyten

et al. (1994), however, found moiré fringes and tetragonal-phase diffraction spots at

voidites that gave a strong nitrogen signal; see Fig. 5.64b. Such differences might

result from different geological conditions during the diamond formation.

Very small (0.5–10 nm) crystals of diamond have been found in chondritic mete-

orites. Their carbon K-edge (Fig. 5.65c) showed a prominent feature just below the

main absorption threshold, characteristic of transitions to π

∗

states in sp

2

-bonded

carbon and indicating that graphitic or amorphous carbon is present at the surface

of each grain. This observation supported the proposal that the diamond was formed

by pressure conversion of graphite during grain–grain collisions in interstellar space

(Blake et al., 1988).

Thin films of diamond grown by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) onto single-

crystal silicon substrates are usually found to be polycrystalline. From the presence

of a π

∗

peak at 285 eV, Fallon and Brown (1993) concluded that amorphous car-

bon is present at grain boundaries and at the free surface. From its plasmon energy

and low estimated sp

3

fraction, this carbon is believed to be nonhydrogenated; see

Fig. 5.66. A lack of epitaxy may result from the presence of a sub-nanometer layer

of amorphous carbon, visible at the substrate/film interface in STEM images of

cross-sectional specimens formed from energy losses just before and just after the

diamond K-threshold (Muller et al., 1993). However, some deposition conditions

give areas with oriented growth and absence of an interfacial layer (Tzou et al.,

1994).

A metastable hexagonal form of diamond (lonsdaleite) can be synthesized by

shock-wave conversion of graphite. Its plasmon peak occurs at slightly lower

energy (32.4 eV) than cubic diamond, possibly due to the presence of lattice

defects (Schmid, 1995). Moreover, its plasmon peak is more symmetrical than cubic

diamond, which has a “shoulder” around 23 eV arising from interband transitions.

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 383

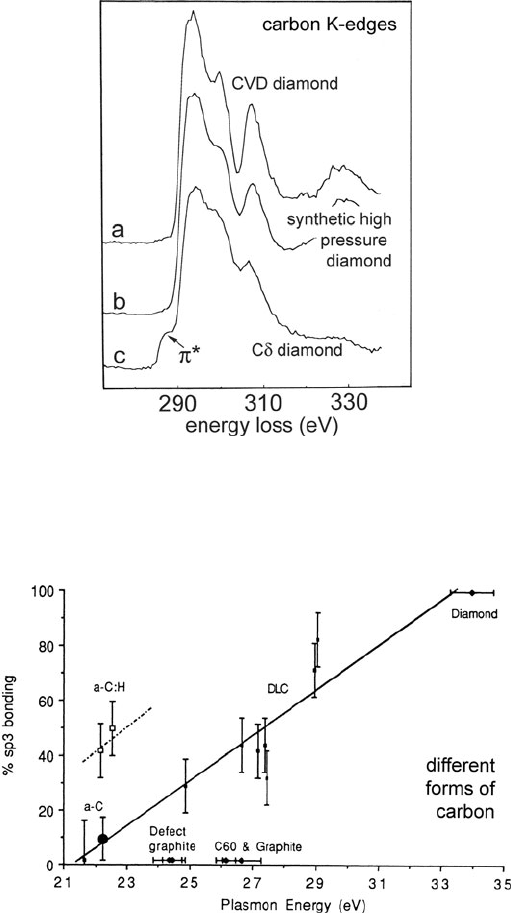

Fig. 5.65 Carbon K-edges of (a) synthetic low-pressure CVD diamond, (b) synthetic high-

pressure diamond, and (c)Cδ component of the Allende CV3 meteorite. The arrow marks pre-edge

structure due to 1s → π ∗ transitions, characteristic of sp

2

bonding. From Blake et al. (1988),

copyright Nature Publishing Group

Fig. 5.66 Percentage of sp

3

bonding (measured from the C-K → π

∗

; intensity) as a function of

plasmon energy (main peak in the low-loss spectrum) for different forms of carbon. The solid line

indicates the general trend for nonhydrogenated carbon films. The presence of hydrogen lowers the

film density and plasmon energy (dotted line). The large filled circle at the bottom left represents

grain-boundary amorphous carbon. From Fallon and Brown (1993), copyright Elsevier

384 5 TEM Applications of EELS

5.7.3.1 Measurement of Bonding Type

Both the low-loss and K-edge spectra of diamond and graphite differ substantially,

enabling EELS to provide a measure of the relative sp

3

(diamond-like) and sp

2

(graphitic) bonding in various forms of carbon.

Transparent films of tetrahedral-amorphous carbon (ta-C, also known as hard

carbon or amorphous diamond-like carbon, a-DLC) can be made by laser ablation

or by creating a vacuum arc on a graphite cathode, with magnetic filtering to ensure

that 20–2000 eV ions are selected from the plasma. They have high hardness and a

density about 80% of the diamond value (3.52). Berger et al. (1988) determined the

type of bonding in these films i n terms of the parameter

R =

I

K

(π

∗

)

I

K

()

I

l

()

I

0

(5.33)

where I

K

(π

∗

)istheK-shell intensity in the π

∗

peak and I

K

() represents K-loss

intensity integrated over an energy range (at least 50 eV) starting at the threshold.

The factor I

1

()/I

0

(ratio of low-loss and zero-loss intensities) corrects for plural

(K-shell + plasmon) scattering present in I

K

() but not in I

K

(π

∗

); this factor should

be omitted for spectra that have been deconvolved to remove plural scattering. The

fraction of graphitic bonding is then evaluated as f = R/R

g

, where R

g

is the value

of R measured from the spectrum recorded from polycrystalline graphitized carbon.

Papworth et al. (2000)usedC

60

as their standard because its K-edge is less depen-

dent on specimen orientation. By fitting to peaks at 285, 287, and 293 eV, they

concluded that their evaporated amorphous carbon was 99% sp

2

-bonded.

A variation on the above procedure is to measure the intensity within a narrow

window

1

centered around the π

∗

peak and over a broader window

2

under the

σ

∗

peak, the fraction p of sp

2

bonds being given by

I

π

(

1

)

I

σ

(

2

)

= k

p

4 −p

(5.34)

where the value of k is again obtained by comparison with graphite (p = 1). With

1

= 2 eV and

2

= 8 eV, this procedure was found to yield a variability of about

5% and an absolute accuracy of ±13% in the sp

3

fraction when applied to a large

number of ta-C films (Bruley et al., 1995).

For ta-C, Eq. (5.33) predicts that 15% of the bonding is sp

2

, the remainder being

sp

3

(assuming sp

1

bonding to be absent). This diamond-like bonding may occur

because a graphitic surface layer is subjected to high compressive stress or high local

pressure by the energetic incident ions. The ta-C films contain no hydrogen, unlike

amorphous silicon and germanium films in which hydrogen is required to stabilize

the structure. The low-loss spectrum contains a weak peak at 6 eV (characteristic

of π electrons) and energy-selected imaging at this energy has shown that ta-C can

contain a low density of disk-like inclusions that are mostly sp

2

bonded (Yuan et al.,

1992).

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 385

By adjusting the ion energy selected by the magnetic filtering, the sp

3

fraction

and film density of ta-C (measured from the plasmon energy or by RBS) can be var-

ied. Plotting sp

3

fraction against plasmon energy, the data lie close to a straight line

with bulk diamond as an extrapolation; see Fig. 5.66. Amorphous carbon produced

from an arc discharge between pointed carbon rods (a common method of mak-

ing TEM support films) also lies on this line, its sp

3

fraction being typically 8%.

A variation of Fig. 5.66 is to plot sp

2

fraction against the inverse square of the plas-

mon energy, in which case straight line behavior accords with a free-electron model

(Bruley et al., 1995). Plasmon-loss and π

∗

-peak measurements have been used to

investigate the variation of film density and sp

2

fraction with deposition method

(e-beam evaporation, ion sputtering, and laser ablation) and with temperature and

thermal conductivity of the substrate (Cuomo et al., 1991).

By introducing N

2

into the cathodic arc, up to 30% of nitrogen can be incorpo-

rated into ta-C, with a gradual loss of sp

3

bonding and reduction in compressive

stress with increasing nitrogen content. The fine structures of the nitrogen and car-

bon K-edges are similar at all compositions, suggesting substitutional replacement

of carbon by nitrogen (Davis et al., 1994).

Amorphous carbon containing hydrogen (a-C:H), in the form of a hard and trans-

parent film, is produced by plasma deposition from a hydrocarbon. Fink et al. (1983)

used a Bethe sum method, based on Eq. (4.32), to measure the sp

2

fraction in these

materials as f = R/R

g

, where

R =

n

eff

(π)

n

eff

()

=

+

δ

0

E Im(−1/ε)dE

+

0

E Im(−1/ε)dE

(5.35)

The energy-loss function Im [−1/ε(E)] is obtained from Kramers–Kronig analysis

(Section 4.2); the energy was taken as 40 eV and δ as the intensity minimum

(about 8 eV) between the π-resonance peak (about 6 eV) and the (σ + π) reso-

nance (around 24 eV). This procedure assumes that inelastic intensity below E = δ

corresponds entirely to excitation of carbon π-electrons (ignoring any contribution

from hydrogen), by analogy with graphite where Eq. (5.35)givesR

g

= 0.25, con-

sistent with one π electron out of four valence electrons per atom (Taft and Philipp,

1965).

For hydrogenated films, Fink et al. (1983) obtained R ≈0.08, implying that one-

third of the bonding is graphitic. Upon annealing at 650

◦

C, the graphitic fraction

increased to two-thirds and the (σ +π) plasmon energy decreased by 2 eV. Since

annealing removes hydrogen from the films, this decrease in plasmon energy may

be partly due to loss of the electrons previously contributed by hydrogen atoms.

Upon annealing to 1000

◦

C, the plasmon energy increased, indicating an increase

in density (Fink, 1989). Measurement of the π -peak energy versus scattering angle

gave a dispersion coefficient close to zero, implying that the π electrons undergo

single electron rather than collective excitation. The π-electron states are therefore

localized in a-C:H, similar to states within the “mobility gap” of amorphous semi-

conductors. Upon removal of hydrogen by annealing, the π peak became dispersive,

386 5 TEM Applications of EELS

indicating formation of a band of delocalized states. Fink (1989) interpreted these

results in terms of model for a-C:H in which π -bonded clusters are surrounded by a

sp

3

matrix.

Daniels et al. (2007) used EELS and x-ray diffraction to study the heat treatment

of petroleum pitch at temperatures up to 2730

◦

C. The volume plasmon (σ+π) peak

was found to give a good measure of graphitic character; the K-edge σ

∗

fine structure

provided an indicator of the degree of longer range order.

McKenzie et al. (1986) studied fine structure of the carbon K- and Si L-edges

in a-Si

1−x

C

x

:H alloys as a function of composition and used chemical shifts to

derive information about compositional and structural disorder. Amorphous car-

bon/nitrogen alloys (CN

x

, where x < 0.8) have also been studied; the carbon and

nitrogen K-edges provide a convenient measurement of film composition, while

the presence of a strong π

∗

peak indicates that the material remains primarily sp

2

bonded (Chen et al., 1993). However, the relative strength of the 287-eV peak falls

with increasing nitrogen content (Papworth et al., 2000; Yuan and Brown, 2000).

Ferrari et al. (2000) examined a variety of amorphous carbon films, some

containing hydrogen or nitrogen, and deduced physical density from both the

x-ray reflectivity and the volume plasmon energy E

p

, assuming that C, N, and H

atoms contribute 4, 5, and 1 electrons, respectively. By comparison with E

p

=

(h/2π)(ne

2

/ε

0

m)

1/2

, they concluded that the effective mass is m = 0.87m

0

in

carbon systems.

Braun et al. (2005) have pointed out that TEM-EELS K-edges consistently show

less fine structure than x-ray absorption spectra (at least for diesel soot), which they

attribute to radiation damage caused by the electrons.

5.7.4 Polymers and Biological Specimens

Microtomed thin sections of polymers and biological tissue present problems for

analytical TEM because of their radiation sensitivity and low image contrast.

Energy-filtered imaging can be used to increase the contrast or to examine thicker

sections, as discussed in Section 5.3. From spectrum image data, Hunt et al. (1995)

formed “chemical” maps at 7 eV loss (characteristic of double bonds) showing

polystyrene-rich regions in unstained sections of a polyethylene blend. More et al.

(1991) used parallel recording EELS to detect sulfur in a 0.5-μm

2

area of polyether

sulfone (PES), for which the maximum safe dose (deduced from decay of the 6-eV

peak in a time-resolved series of spectra) was estimated as 0.24 C/cm

2

. Rao et al.

(1993) detected a 15% increase in carbon concentration in 40-nm-sized regions of

ion-implanted polymers by using K-edges together with low-loss spectra (to allow

for differences in local thickness). Kim et al. (2008) used differences in low-loss

fine structure (revealed by energy-filtered cryo-TEM imaging) to study the copoly-

merization of PDMS/acrylate mixtures; see also the review of Libera and Egerton

(2010).

Differences in carbon K-edge π

∗

-peak energy were used by Ade et al. (1992)

to image polymer blends and chromosomes in a scanning transmission x-ray

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 387

microscope (STXM) with 55-nm spatial resolution. Similar ELNES imaging could

be performed in an energy-selecting TEM with greater spatial resolution but with

higher radiation dose. Du Chesne (1999) provides various examples of zero-loss,

low-loss, and core-loss imaging of polymers.

Biological TEM analysis is always strongly dependent on specimen prepara-

tion. The ability to prepare ultrathin sections minimizes the unwanted background

in core-loss spectra (Section 3.5) and mass thickness contributions to core-loss

images (Section 2.6.5). For phosphorus L-edge measurements, the optimum speci-

men thickness has been said to be 0.3 times the total inelastic mean free path (Wang

et al., 1992), and for 100-keV primary electrons, this corresponds to about 100 nm

of dry tissue or 60 nm of hydrated tissue. Rapid freezing techniques reduce the

migration or loss of diffusible species, as needed for quantitative analysis.

Leapman and Ornberg (1988) point out that carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen are the

major constituents of biological specimens and their ratio (together with P and S)

can be useful for identifying proteins and nucleotides (DNA, ATP, etc.). In fluoro-

histidine, they measured N:O:F ratios within 10% of the nominal values, provided

the radiation dose was kept below 2 C/cm

2

. Fluorine is of potential importance as a

label, for example, for identifying neurotransmitters in organelles (Section 5.4.4).

Na, K, Mg, Cl, P, and S are typically present as dry mass fraction between 0.03

and 0.6% (25–500 mmol/kg dry weight, equivalent to 5–100 mmol/kg wet wt.,

assuming 80% water content). Although these elements can be analyzed by EDX

spectroscopy (Shuman et al., 1976; Fiori et al., 1988), mass loss and specimen drift

limit the spatial resolution. In the case of EELS, higher sensitivity for S, P, Cl, and

Fe is obtainable by choosing L-edges, with their higher scattering cross sections.

The L-edges of sodium and magnesium lie too low in energy while that of potas-

sium overlap strongly with the carbon K-edge, so these three elements are more

easily detected by EDX methods (Leapman and Ornberg, 1988).

Calcium is present in high concentrations (≈10%) in mineralizing bone but oth-

erwise at the millimolar level. At this concentration, a 50-nm-diameter region in

a 50-nm-thick specimen contains only about 50 Ca atoms, so measuring small

changes in concentration requires very high sensitivity (Shuman and Somlyo, 1987;

Leapman et al., 1993b). MLS processing and component analysis (Section 4.5.4)

are likely to be useful tools.

EFTEM elemental mapping of phosphorus, sulfur, and calcium was used by

Ottensmeyer and colleagues to show the structure of chromatin nucleosomes

and mineralizing cartilage (Bazett-Jones and Ottensmeyer, 1981; Arsenault and

Ottensmeyer, 1983; Ottensmeyer, 1984). Very thin specimens ensured low plural

scattering and mass thickness contributions to the image, but most of these ele-

mental maps were obtained simply by subtracting a scaled pre-edge image from

the post-edge image. With digital processing, pre-edge modeling can be carried out

at each image point, allowing more accurate background subtraction; see Sections

2.6.5 and 5.3.6. Leapman et al. (2004) have used tomographic energy-filtered imag-

ing to measure the three-dimensional distribution of phosphorus within cells, down

to about 0.5% concentration. A fairly high electron dose (100 C/cm

2

) was required

to record the tilt series, but a resolution below 20 nm was achieved.