Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

348 5 TEM Applications of EELS

E

=

E

1−s

dE

#

E

−s

dE ≈ E

k

(s −1)/(s −2) (5.32)

For scattering through all angles, s is close to 3 for most energy losses (Fig. 3.40),

giving

E

≈ 2E

k

, whereas the core-loss signal is usually measured at energy losses

just above the edge threshold, corresponding to an average loss close to E

k

. As seen

from Fig. 5.30, this lower mean loss implies less localized scattering and a reduced

Borrmann effect (Bourdillon et al., 1981).

In fact, delocalization of the inelastic scattering will reduce both R

EELS

and R

x

in

the case of light elements (such as oxygen) with low threshold energies. Pennycook

(1988) observed that the fractional change in x-ray signal between axial and random

orientations is reduced for photon energies below 5000 eV (by a factor of 0.6 at

1300 eV). Calculations of Spence et al. (1988) showed the reduction to be less for

planar channeling; Qian et al. (1992) observed orientation dependence of the oxygen

K-signal by both EELS and EDX spectroscopy but they emphasize that a correction

factor for delocalization is necessary for quantitative analysis. Rossouw et al. (1989)

have argued that their statistical procedure makes approximate allowance for the

degree of localization.

Fortunately, the localization and orientation dependence in EELS can be

increased (at the expense of reduced signal) by collecting electrons deflected

through larger angles. For planar channeling (incident beam far from a major zone

axis), the chosen scattering angle can be made arbitrarily large (without affecting the

blocking or channeling conditions) by displacing the collection aperture in a direc-

tion parallel to the appropriate Kikuchi band (Taftø and Krivanek, 1981). Beam

deflector coils can translate the diffraction pattern in an appropriate direction rel-

ative to the spectrometer entrance aperture, making use of the observed Kikuchi

bands (Taftø and Krivanek, 1982a).

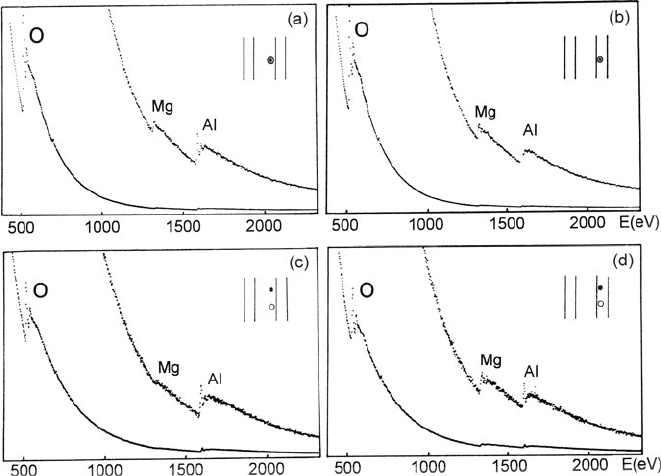

An example of these orientation effects is shown in Fig. 5.35. Spectra (a) and (b)

were recorded with the collection aperture centered around the zero-order diffrac-

tion spot; the ratio of the Mg and Al K-edge intensities varies by only a factor of

1.8 when the specimen orientation is changed so that the Kikuchi line at the edge of

the (400) band crosses the collection aperture. In cases (c) and (d), the diffraction

pattern has been displaced parallel to the (400) band in order to increase the local-

ization of the inelastic scattering entering the aperture; as a result, the Al/Mg ratio

changes by a factor of 9 as the specimen is tilted through the (400) Bragg condition.

If the illumination and detector apertures are placed on opposite sides of a Kikuchi

line, the channeling and blocking effects largely cancel (Taftø and Krivanek, 1981).

To determine the atomic site of a particular element from planar channeling,

the specimen orientation must be carefully chosen. In the case of minerals with

the spinel structure (general formula AB

2

O

4

), the incident beam should be nearly

parallel to (800) planes but away from a principal zone axis. The standing-wave

field is then determined mainly by those (800) planes that contain all of the oxygen

atoms and two-thirds of the metal atoms on octahedral sites (Taftø et al., 1982). The

remaining metal atoms occur in tetrahedral coordination on the intervening (800)

planes and are strongly excited if the incident beam direction lies just outside the

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 349

Fig. 5.35 Core-loss spectra measured from a normal spinel (MgAl

2

O

4

) with the incident beam

nearly parallel to (100) planes. Insets show the location of the incident beam (solid circle)and

collection aperture (open circle) relative to the (400) and (800) Kikuchi bands. In (a)and(b), the

collection a perture is centered about the illumination axis; the Mg/Al intensity ratio increases by

a factor of 1.8 as the crystal is tilted so t hat the aperture lies outside rather than inside the (400)

band. In (c)and(d), the collection aperture has been displaced by 10 mrad parallel to the (400)

band to increase the localization of core-loss scattering; the Mg/Al ratio then increases by a factor

of 9 between the two crystal orientations. From Taftø and Krivanek (1982a), copyright Elsevier

(400) Kikuchi band (Fig. 5.35b). Conversely, the octahedral (and oxygen) atoms are

strongly excited if the incident beam lies just inside the (400) band (Fig. 5.35a). In

a normal spinel, A atoms are on tetrahedral sites and B atoms on octahedral sites;

in an inverse spinel, the tetrahedral sites are filled by half of the B atoms, octahedral

sites accommodating the A and remaining B atoms. Provided components A and B

give rise to clearly observable ionization edges, the orientation dependence of the

edge can be used to determine whether a given spinel has the normal or inverse

structure, even if both A and B contain a mixture of two different elements (Taftø

et al., 1982).

In mixed-valency compounds, one of the elements (such as a transition metal) is

present as differently charged ions whose ionization edges may be distinguishable

as a result of a chemical shift (Section 3.7.4). For example, Fe

2+

and Fe

3+

ions in

chromite spinel give rise to sharp white-line threshold peaks shifted by about 2 eV.

Taftø and Krivanek (1982b) utilized this chemical shift, together with the orientation

dependence of the ionization edges, to show that their sample of chromite spinel

350 5 TEM Applications of EELS

contained all of the Fe

2+

atoms on tetrahedral sites and all of the Fe

3+

atoms on

octahedral sites.

Channeling experiments require specimens containing single-crystal regions as

large as the incident beam diameter, usually several nanometers, because the con-

vergence of smaller probes reduces the orientation effect. The specimen thickness

should be at least equal to the extinction distance ξ

g

in order to provide a pronounced

variation in current density within each unit cell. Otherwise the orientation depen-

dence will be weak and the measurement prone to statistical error. The extinction

distance not only is proportional to the incident electron velocity, but also depends

on crystal orientation and atomic number (Hirsch et al., 1977; Reimer and Kohl,

2008). For 100-keV electrons and a strong channeling direction, ξ

g

≈ 50 nm for

carbon, decreasing to 20 nm for gold.

5.6.2 Core-Loss Diffraction Patterns

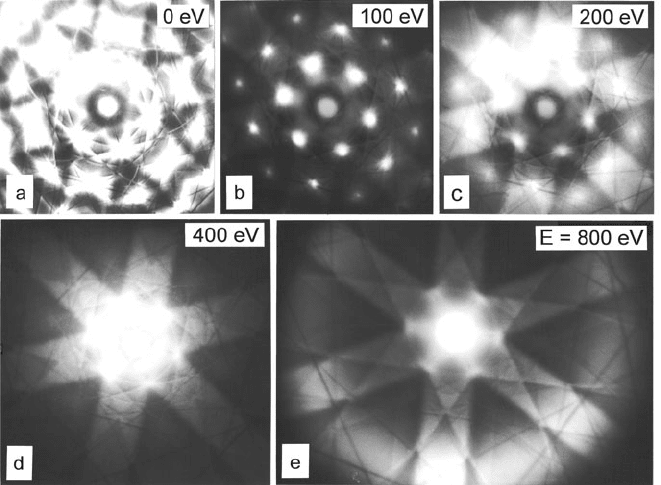

In the previous section, we discussed the variation of core-loss intensity as the speci-

men is tilted, keeping the collection aperture fixed. We now consider the variation in

intensity with scattering angle for a fixed sample orientation. An amorphous speci-

men has an axially symmetric scattering distribution; at low energy loss the intensity

is peaked about the unscattered direction, while for energy losses far above an ion-

ization threshold it takes the form of a diffuse ring, representing a section through

the Bethe ridge (Fig. 3.31). In the case of a crystalline specimen, elastic scattering

results in a diffraction pattern containing Bragg spots (or rings, for a polycrystal)

and Kikuchi lines or bands. Energy-filtered diffraction patterns can be recorded in a

scanning transmission electron microscope by rocking the incident beam in angle or

by using post-specimen deflection coils to scan the pattern across a small-aperture

detector, but a more efficient procedure is to use a stationary incident beam and an

imaging filter (Section 2.6).

At low energy loss, the diffraction pattern resembles the zero-loss pattern, but

with the diffraction spots broadened by the angular width of inelastic scattering.

This regime corresponds to a median angle of inelastic scattering θ less than the

angular separation between Bragg beams, approximately the lowest-order Bragg

reflection angle θ

B

. Taking the delocalization length as L ≈ 0.6λ/

θ

(Section

5.5.3) and using the Bragg equation λ =2dθ

B

, this condition is equivalent to L>d

or (since the interplanar spacing d is comparable to the lattice constant) localization

of the inelastic scattering exceeding the unit-cell dimensions. Under these condi-

tions, inelastic scattering does not greatly change the angular distribution of elastic

scattering and diffraction contrast is preserved in energy-selected images of defects

such as stacking faults and dislocations (Craven et al., 1978).

At higher energy loss, the inelastic scattering becomes highly localized and the

average inelastic scattering angle exceeds the angular separation of the diffracted

beams. Bragg spots therefore disappear from the energy-filtered diffraction pattern,

which starts to resemble the Kossel pattern from an isotropic source of electrons

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 351

Fig. 5.36 Energy-filtered diffraction patterns of a thin silicon crystal with the incident beam close

to a 111 axis. (a) Zero-loss pattern, overexposed to show Kikuchi lines resulting from phonon

scattering. (b)–(e): inelastic patterns recorded at multiples of 100 eV, showing the broadening and

diminution of diffraction spots, the development of Kikuchi bands, and the emergence of a diffuse

ring representing the Bethe ridge

inside the crystal or the Kikuchi pattern obtained from a thick specimen; see

Fig. 5.36c. If the specimen is sufficiently thin, a diffuse ring representing the Bethe

ridge is visible at high energy loss, as in Fig. 5.36e.

By subtracting diffraction patterns recorded just above and below an ioniza-

tion edge of a chosen element, a core-loss diffraction pattern can be produced.

Spence (1980, 1981) carried out dynamical calculations to determine the condi-

tions under which this pattern has the symmetry of the local coordination of the

selected element, rather than the symmetry of the whole crystal. He found that both

the localization of the core-loss scattering and the inelastic spread 2t

θ

within the

specimen thickness t must be less than unit-cell dimensions. For E

0

= 100 keV

and an inorganic crystal with small unit cell (0.6 nm), the first condition requires

E

k

> 200 eV; the second implies t <50nmforE

k

≈ 200 eV or t <15nmfor

E

k

≈ 1000 eV. The requirements are relaxed for larger unit cells. Core-loss diffrac-

tion could therefore provide an alternative to channeling and ELNES techniques for

determining the atomic site of light atoms in a crystal.

From measurements on LaAlO

3

, Midgley et al. (1995) concluded that exami-

nation of HOLZ intensities in a core-loss CBED pattern can be used to determine

which atomic species (or which sublattice in a complex crystal) contributes most to a

352 5 TEM Applications of EELS

particular Bloch state, information that might contribute to the solution of unknown

crystal structures. Botton (2005) has demonstrated asymmetry in K-loss diffrac-

tion patterns of graphite recorded at the π

∗

and σ

∗

energies with a tilted specimen

and has proposed energy-filtered diffraction as a means of studying the bonding in

anisotropic materials.

5.6.3 ELNES Fingerprinting

In compounds containing coordinate bonding, such as minerals and organic com-

plexes, it is sometimes desirable to know the coordination number and the sym-

metry of the nearest-neighbor ligands surrounding a metal ion. As discussed in

Section 3.8.1, the energy-loss near-edge structure (ELNES) of an ionization edge

represents approximately a local densities of states at the atom giving rise to the

edge. This interpretation is consistent with multiple scattering (XANES) calcula-

tions of the backscattering of the ejected electron (Section 3.8.4), which show that

the scattering is quite localized, involving just a few near-neighbor shells (Wang

et al., 2008a).

Sometimes the scattering of the ejected core electron is mostly from a single shell

of atoms, where these are strongly scattering species such as the O

2−

or F

−

ions. In

effect, the ions form a cage or potential barrier that impedes the escape of the inner-

shell electron (Bianconi et al., 1982). The near-edge fine structure then serves as a

coordination fingerprint when applied to mineral specimens (Taftø and Zhu, 1982).

In the case of polymers and macromolecules, the XANES structure can provide a

fingerprint of the functional groups that act as building blocks for the entire structure

(Stohr and Outka, 1987). The fact that the scattering is localized allows molecular

orbital calculations to be used as a basis for interpreting and labeling the peaks

(Sauer et al., 1993).

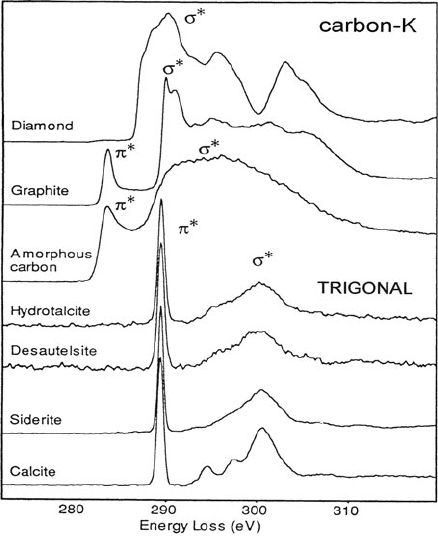

ELNES where the excited atom is in trigonal planar coordination (three nearest

neighbors lying in a plane) is shown in Fig. 5.37. The carbon K-edge of a carbonate

group is characterized by a narrow π

∗

peak followed (at 10–11 eV separation) by

a broader σ

∗

peak, quite different from the fine structure of carbon in any of its

elemental forms. The same kind of K-edge fine structure is observed for prismatic

(nonplanar) coordination (Brydson, 1991) and for trigonally coordinated boron in

the mineral vonsenite (Rowley et al., 1990).

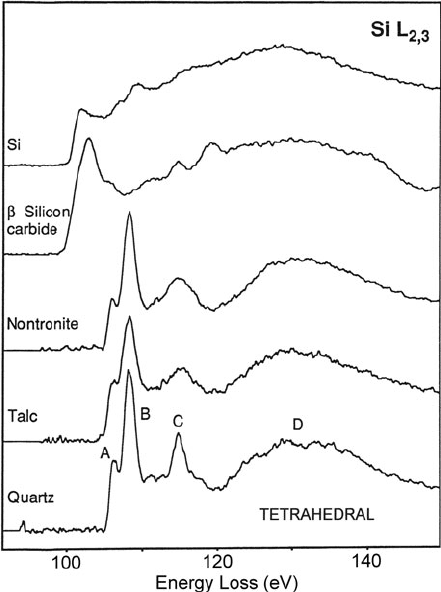

Situations involving tetrahedral coordination are shown in Fig. 5.38. The Si

L-edge of the SiO

4

tetrahedron shows two sharp peaks (separated by ≈7eV)fol-

lowed by a third prominent broad peak separated about 22 eV from the first peak.

When observed at 0.5-eV energy resolution, the first peak is seen to contain a smaller

peak about 1.9 eV lower in energy. A similar peak structure was observed for the

chlorate, sulfate, and phosphate anions (Hofer and Golub, 1987; Brydson, 1991)

with some differences of detail.

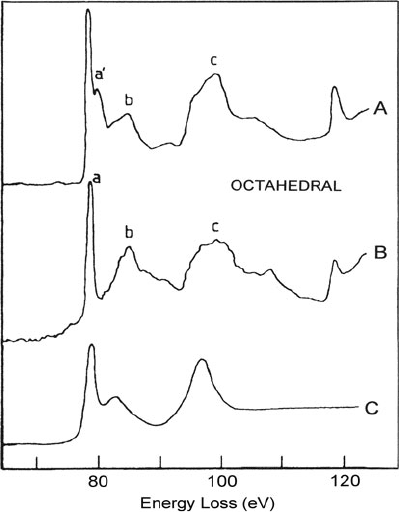

Examples of octahedral coordination are shown in Fig. 5.39. A sharp peak (a) is

followed by t wo broader peaks (b) and (c), displaced by about 7 and 19 eV. Fairly

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 353

Fig. 5.37 Carbon K-edges of

minerals containing the

carbonate anion, an example

of trigonal planar bonding,

compared with the K-edges of

elemental carbon. Spectra

(energy resolution 0.5 eV)

were deconvolved to remove

plural scattering and peak

distortion due to the

asymmetrical energy

distribution of the

field-emission source. From

Garvie et al. (1994),

copyright Mineralogical

Society of America, with

permission

similar structures are observed at the K-edges of MgO, where both Mg and O atoms

are octahedrally coordinated (Colliex et al., 1985; Lindner et al., 1986).

Several factors complicate this simple concept of coordination fingerprints. If the

symmetry of the coordination is distorted, near-edge peaks are broadened or split

into components (Buffat and Tuilier, 1987; Brydson et al., 1992b). For example, the

Si L

23

edge of zircon shows five peaks in place of the first two that characterize

SiO

4

tetrahedra (McComb et al., 1992). Atoms outside the first coordination shell

may contribute, which probably explains the two additional peaks seen in the calcite

carbon K ELNES (Fig. 5.37). In fact, Jiang et al. (2008) found that the most signif-

icant differences between the ELNES of MgO and Mg(OH)

2

arose from atoms in

the second and third coordination shells. Core hole effects and crystal-field splitting

cause the L

3

and L

2

edges of transition metals to appear as two components when

observed at high energy resolution (Krivanek and Paterson, 1990; Krishnan, 1990);

modeling of these effects could yield information relating to crystal field strength

(Garvie et al., 1994; Stavitski and de Groot, 2010).

In addition, several factors can cause apparent differences in structure measured

from different specimens or in different laboratories. If a thermionic electron source

(energy width typically 1–2 eV) is used, the energy resolution may be insufficient to

resolve peak splittings such as those visible in Fig. 5.38. If recorded with electrons

354 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Fig. 5.38 Silicon L

23

edges

of three silicates containing

SiO

4

tetrahedra, compared

with the L

23

edges of SiC and

Si. Spectra (energy resolution

0.5 eV) were deconvolved to

remove plural scattering and

peak distortion due to the

asymmetrical energy

distribution of the

field-emission source. From

Garvie et al. (1994),

copyright Mineralogical

Society of America, with

permission

from a cold field-emission source, peak shapes may be distorted because of the

asymmetry of the emission profile, as seen in the zero-loss peak. If the specimen

thickness exceeds a few hundred nanometers, the overall shape of the ionization

edge is modified by plural scattering (Section 3.7.3), increasing the heights of peaks

occurring 15 eV or more from the threshold. This distortion can be removed by

Fourier deconvolution, which can also correct for the asymmetry of the emission

profile; see Appendix B.

A small collection angle (<15 mrad at 100 keV) simplifies ELNES interpreta-

tion by ensuring that nondipole transitions are excluded, although these transitions

might be used creatively to explore the wavefunction symmetry (Auerhammer and

Rez, 1989). A single crystal is not necessary; in fact, the fine structure may be

more reproducible if recorded from a polycrystalline area containing several grains,

suppressing orientation effects (Brydson et al., 1992a, b), or under magic-angle

conditions (see Appendix A). In principle, crystal anisotropy provides additional

information about the directionality of bonding but requires careful control over the

specimen orientation.

Because the initial-state wavefunction is more localized, higher energy edges

may offer more characteristic fingerprints. This consideration favors K-edges rather

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 355

Fig. 5.39 Aluminum L

23

edge in (A) chryoberyl and

(B) rhodizite, together with

(C) ICXANES calculations

for aluminum octahedrally

coordinated by a single shell

of oxygen atoms. From

Brydson et al. (1989),

reproduced with permission

from The Royal Society of

Chemistry, http://dx.doi.org/

10.1039/C39890001010

than the low-energy N

23

or O

23

edges, whose plasmon-like shape is practically inde-

pendent of the atomic environment (Colliex et al., 1985). But the 1s states for Z >

14 and 2p states for Z > 28 have natural widths that exceed 0.5 eV (Fig. 3.51a), so

K-edges above 2000 eV and L

23

edges above 1000 eV can be expected to show less

fine structure.

ELNES fingerprinting has been applied to several materials science problems. By

comparing the Al K-edges of ion-thinned specimens of blast-furnace slag cement

with those recorded from minerals (orthoclase, pyrope, hydrotalcite) and with mul-

tiple scattering calculations, Brydson et al. (1993) concluded that two phases were

present: one with Al atoms substituted for Si at tetrahedral sites and the other

(Mg-rich) phase containing Al at octahedral sites. Bruley et al. (1994) recorded

Al L

23

spectra from a diffusion-bonded niobium/sapphire interface. Agreement was

obtained with multiple scattering calculations by assuming an interfacial monolayer

of aluminum atoms tetrahedrally bonded to three oxygen and one Nb atom, with

Al–Nb bonds providing the cohesive energy. Interfaces produced by molecular beam

epitaxy showed no modification of the Al–L ELNES at the interface, suggesting that

the sapphire was terminated by oxygen and that charge transfer from Nb provided

the cohesive force. Similar spatially resolved ELNES studies were used to establish

the symmetry and coordination number of Al atoms at a 35.2

◦

grain boundary in

sapphire (Bruley, 1993).

356 5 TEM Applications of EELS

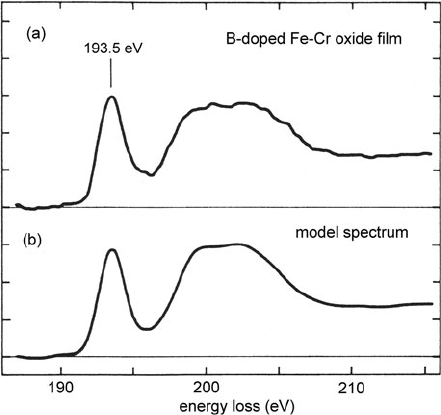

Fig. 5.40 (a) Boron-K

ELNES of a B-doped Fe/Cr

oxide layer formed on

stainless steel in superheated

steam. (b) Composite

spectrum formed by adding

boron K-edges recorded from

colemanite (BO

3

fingerprint)

and rhodizite (containing

BO

4

)intheratio7:3.From

Sauer et a l. (1993), copyright

Elsevier

Another example of the use of ELNES is the work of Rowley et al. (1991)onthe

oxidation of Fe/Cr alloys in superheated steam. The presence of boron increases the

oxidation resistance by creating a diffusion barrier, a thin microcrystalline film of

composition (M

x

B

1−x

)

2

O

3

, where M =Fe, Cr, or Mn. The boron K-edge (Fig. 5.40)

exhibits a sharp peak at 194 eV and a broad peak containing two components cen-

tered on 199 and 203 eV, believed to represent BO

3

and BO

4

borate groupings

from comparison with the K-edges of vonsenite and rhodizite. The proportions of

these two components varied as the electron probe was moved across the sample,

suggesting that the film consisted of separate phases of MBO

3

and M

3

BO

6

(Sauer

et al., 1993). In the case of heavy boron doping, a small prepeak preceding the 194-

eV maximum was taken to indicate the presence of a boride, whose π

∗

peak was

shifted down in energy due to the lower effective charge on the boron atom.

Using thin films of silicon alloys, Auchterlonie et al. (1989) showed that Si atom

nearest neighbors (B, C, N, O, or P) can be distinguished using the fine structure

of the Si L

23

edge, as well as from the energy (chemical shift) of the first ELNES

peak. The bonding type in various forms of carbon and carbon alloys can be mea-

sured from the π

∗

/σ

∗

ratio at the carbon K-edge, as discussed in Section 5.7.3.As

discussed in Chapter 3, ELNES fine structure can also serve as a guide to the den-

sities of unoccupied states in a solid and can therefore be used as a check on band

structure calculations.

Bianconi et al. (1983a) predicted that the energy of the broad shape resonance

peak (due to transitions to σ

∗

states) is proportional to 1/R

2

, where R is the nearest-

neighbor distance and the proportionality constant depends on the type of nearest

neighbors. This simple rule could be useful (as in XAS) for measuring changes in

bond length.

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 357

There has recently been much interest in using ELNES to investigate the

structure of interfaces, particularly within materials used in the electronics indus-

try. MacKenzie et al. (2006) prepared cross-sectional TEM samples containing a

Si/SiO

2

/HfO

2

/TiN/poly-Si gate stack and obtained evidence of interfacial reaction

between the TiN gate and the surrounding layers, together with a silicon oxyni-

tride phase at the TiN/Si interface. Other microelectronics examples are given in

Section 5.7.1. A review of ELNES as a tool for investigating electronic structure on

a nanometer scale is given by Keast et al. (2001).

5.6.4 Valency and Magnetic Measurements

from White-Line Ratios

As discussed in Section 3.7.1,theL

2

and L

3

edges of transition metals are char-

acterized by white-line peaks at the ionization threshold. The energy separation of

these peaks reflects the spin-orbit splitting of the initial states of the transition; their

prominence (relative to the higher E continuum and to each other) varies with atomic

number Z, as seen in Fig. 3.45.

A decrease in white-line intensity with increasing Z is understandable, since

the d-states fill up and the density of empty states just above the Fermi level

decreases. One might expect I

w

∝ (10 − n

d

), where I

w

is the s um of the two

white-line intensities (relative to the continuum) and n

d

is the d-state occupancy.

Measurements on metallic films (Pearson et al., 1993) are in approximate agreement

with this; see Fig. 5.41c, d. Figure 5.41a, b indicates one procedure for obtaining the

white-line/continuum ratio: the continuum is measured as an integral over a 50-eV

window, starting 50 eV beyond the edge, and linearly extrapolated to an energy

loss corresponding to the center of each white line so that the white-line intensity

(shaded area) can be measured.

The variation of I

w

with n

d

has been used to measure charge transfer in disordered

and amorphous copper alloys (Pearson et al., 1994). Corrections were made for

changes in matrix element and the Cu white-line intensity was measured relative to

a normalized L

23

edge of metallic copper, which has no white lines. Each copper

atom was found to lose 0.2 ± 0.06 electrons when alloyed with Ti or Zr, between

0 and 0.06 electrons when alloyed with Au or Pt, and between 0 and 0.09 electrons

when alloyed with Pt. Electron transfer back to copper was observed after the alloys

became crystalline.

If the matrix element and final densities of states were the same for all of the

excited p-electrons, the intensity ratio R

w

= I(L

3

)/I(L

2

) of the two white-line peaks

should reflect the degeneracy ratio of the initial-state (2p

3/2

and 2p

1/2

) electrons,

namely 4/2 = 2; see Appendix D. But as a result of spin–spin coupling, R

w

depends

on the number of electrons in the final (3d) state and therefore varies with atomic

number and oxidation state (Thole and van der Laan, 1988; de Groot et al., 1991).

This behavior is illustrated for Co and Mn compounds in Fig. 5.42 and provides an

alternative means of measuring valency or oxidation state.