Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

338 5 TEM Applications of EELS

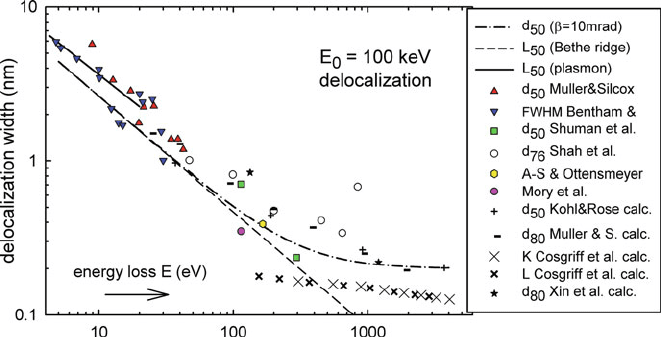

Fig. 5.30 Delocalization distance for inelastic scattering, calculated for 100-keV electrons from

Eq. (5.17) with a free-electron plasmon cutoff (solid line) and a Bethe ridge cutoff (dashed line).

The dash-dot line represents Eq. (5.18)withβ = 10 mrad. Data points represent TEM-EELS

measurements and calculations (see text)

Values of L

50

and d

50

for E

0

= 100 keV and β = 10 mrad are shown in Fig. 5.30.

The main conclusion is that the localization width decreases with increasing energy

loss, from a few nanometers at low energy loss to subatomic dimensions in the case

of higher energy ionization edges.

Figure 5.30 also includes experimental estimates of delocalization. Triangles

(Muller and Silcox, 1995a) represent measurements of inelastic intensity as a func-

tion of distance away from the edge of a 3-nm amorphous carbon film. Inverted

triangles (van Benthem et al., 2001) are based on STEM measurements of a

grain boundary in SrTiO

3

. The two square data points (Shuman et al., 1986)are

based on the measured angular distribution of scattering from carbon and ura-

nium in stained catalase crystals. Hollow circles represent STEM measurements

on LaMnO

3

/SrTiO

3

superlattices (Shao et al. 2011). The hexagonal data point of

Adamson-Sharpe and Ottensmeyer (1981) is based on EFTEM phosphorus map-

ping, while the data point due to Mory et al. ( 1991) is derived from a s tatistical

analysis of STEM images of uranium atoms, recorded with O

45

loss electrons.

Clearly the experimental conditions differ among these measurements, accounting

for some of the scatter in the data. Values in Fig. 5.30 have been adjusted to 100-

keV incident energy, based on Eq. (5.17), although this equation predicts little E

0

dependence (see Fig. 5.31) because changes in λ and θ

E

3/4

largely cancel.

Inelastic scattering distributions can also be calculated from first principles. Kohl

and Rose (1985) employed quantum-mechanical theory to calculate intensity pro-

files for the inelastic image of a single atom, using a dipole approximation. Schenner

and Schattschneider (1994) extended the method to include the effects of spheri-

cal aberration, chromatic aberration, and objective lens defocus, while Muller and

Silcox (1995a) investigated the effect of different detector geometries. Cosgriff et al.

5.5 Spatial Resolution and Detection Limits 339

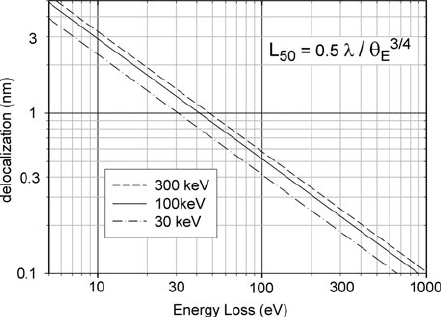

Fig. 5.31 Median

localization width as a

function of energy loss E and

incident electron e nergy E

0

,

evaluated according to

Eq. (5.17). As a result of the

relatively weak dependence

on incident energy, the

delocalization width can be

approximated as (17

nm)/E

3/4

,whereEisineV

(2005) calculated core excitation STEM images of single atoms using Hartree–Fock

wavefunctions. Xin et al. (2010) reported more recent quantum-mechanical cal-

culations within the dipole approximation. Data from all of these calculations are

included in Fig. 5.30.

The solid line in Fig. 5.30 again represents Eq. (5.17) but with an alternative

choice of cutoff angle, based on Eq. (3.50) and more appropriate to plasmon losses.

Note that inelastic delocalization refers to modulations in plasmon signal arising

from changes in chemical composition. Particularly in thicker specimens, variations

in the amount of plural (elastic + plasmon) scattering can introduce diffraction con-

trast into the plasmon-loss image and this contrast has high resolution because of

the more localized nature of elastic scattering (Egerton, 1976c; Craven and Colliex,

1977).

Elastic scattering also complicates the situation for core losses, especially in crys-

talline specimens. Spence and Lynch (1982) calculated the Be K-loss intensity for a

single Be atom on a 7.2-nm gold film, where the delocalization length exceeds the

substrate lattice spacing, resulting in lattice fringe modulation of the K-loss profile

(representing Bragg scattering of Be K-loss electrons in gold). These simulations

showed that atoms not selected by the energy filter may appear in an atomic resolu-

tion inelastic image if the selected energy loss is not sufficiently high. The absence

of boron atoms in atomic resolution LaB

6

energy-selected images was similarly

explained as arising from strong elastic scattering by La columns onto adjacent B

columns, creating a boron signal with little contrast (Lazar et al., 2010). The com-

bined effects of elastic and inelastic scattering in crystalline specimens have been

discussed by Schattschneider et al. (1999, 2000); see Section 3.11.

Kimoto and Matsui (2003) used the focus dependence of energy-filtered lat-

tice fringe contrast to measure a lateral coherence length associated with inelastic

scattering, obtaining values similar to those given by Eq. (5.17).

In addition to its relevance to energy-filtered imaging and spectroscopy, delo-

calization of inelastic scattering is of importance in channeling experiments

340 5 TEM Applications of EELS

(Section 5.6.1). Here core-loss scattering is recorded in a diffraction plane and the

aperture term of Eq. (5.18) is absent, so the localization distance has subatomic

dimensions at high energy loss. This situation allows the nonuniformity in cur-

rent density that arises from channeling (Section 3.1.4) to appreciably affect the

core-loss intensity, dependent on the specimen orientation. Bourdillon et al. (1981)

and Bourdillon (1984) fitted their measured orientation effects with a localiza-

tion distance λ/(4πθ

E

) deduced from time-dependent perturbation theory (Seaton,

1962).

One advantage of the simple treatment represented by Eq. (5.17) is that it pro-

vides an estimate of delocalization in cases where the physical properties of the

specimen are not all known and more sophisticated calculations are not possible.

The formula also suggests how the delocalization distance might vary with the

incident energy E

0

. Taking θ

E

= E/(γ m

0

v

2

)gives

L

50

∝ λ/(θ

E

)

3/4

∝ γ

−1

v

−1

/(γ

−3/4

v

−3/2

) = γ

−1/4

v

1/2

(5.19)

Above 100 keV, this variation barely exceeds 10%; for E

0

= 30 keV the delocaliza-

tion width is about a factor of 20% smaller than at 100 keV; see Fig. 5.31.

5.5.4 Statistical Limitations and Radiation Damage

Because inner-shell ionization cross sections are relatively low, the core-loss inten-

sity may represent a rather limited number of scattered electrons. The spatial

resolution, detection limits, and accuracy of elemental microanalysis are then

strongly influenced by statistical considerations. In the analysis below, we evalu-

ate these statistical constraints on the detection of a small quantity (N atoms per unit

area) of an element that is present in a matrix (or on a support film) having an areal

density of N

t

atoms per unit area, where N

t

>> N. For convenience of notation,

all intensities are assumed to represent numbers of recorded electrons. However, the

radiation fluence or dose D received by the specimen (during spectrum acquisition

time τ ) is in units of Coulombs per unit area.

According to Eq. (4.65), the core-loss signal, recorded with a collection s emi-

angle β and integrated over an energy window , is given by

I

k

≈ NI(β, )σ

k

(β, ) (5.20)

where σ

k

(β, ) is the appropriate core-loss cross section and I(β, ) is the intensity

in the low-loss region, integrated up to an energy loss . If the energy window

contains most of the electrons transmitted through the collection aperture but

this aperture is small enough to exclude most of the elastic scattering (mean free

path λ

e

),

I( β, ) ≈ (I/e)τ exp(−t/λ

e

) = (π/4)d

2

(D/e)exp(−t/λ

e

) (5.21)

5.5 Spatial Resolution and Detection Limits 341

where I is the probe current (in amp), e the electronic charge, and d the probe diam-

eter. We express I(β, ) in terms of an electron dose (or fluence) D because, in the

absence of instrumental drift, radiation damage provides the fundamental limit to

acquisition time and is certainly the main practical limitation for organic specimens.

For small , an additional factor of exp(−t/λ

i

) would be required in Eq. (5.21), λ

i

being a mean free path for inelastic scattering (Leapman, 1992).

An equation analogous to Eq. (5.20) can be written for the background intensity

beneath the edge (as shown in Fig. 4.11):

I

b

≈ N

t

I( β, )σ

b

(β, ) (5.22)

where σ

b

(β, ) is a cross section for all energy-loss processes that contribute to

the background. The core-loss signal/noise ratio for an ideal spectrometer is given

by Eq. (4.61), but using Eq. (2.42) to make allowance for the detective quantum

efficiency (DQE) of t he detector, the measured signal/noise ratio is

SNR = (DQE)

1/2

I

k

/(I

k

+hI

b

)

1/2

≈ (DQE)

1/2

I

k

(hI

b

)

−1/2

(5.23)

where h is the factor representing statistical error associated with background sub-

traction, typically in the range 5–10 for an extrapolated background (Fig. 4.13).

Combining Eqs. (5.20), (5.22), and (5.23), the atomic fraction of an analyzed

element is

f =

N

N

t

=

SNR

σ

k

(β, )

hσ

b

(β, )

N

t

I( β, )

1/2

(DQE)

−1/2

(5.24)

Taking SNR = 3 (98% certainty of detection if Gaussian statistics apply) and using

Eq. (5.21), the minimum detectable atomic fraction is

MAF = f

min

=

3

σ

k

(β, )

1.1

d

hσ

b

(β, )

(DQE)(D/e)N

t

1/2

exp

t

2λ

e

(5.25)

For a given radiation dose D, and assuming the specimen is sufficiently uniform, a

large beam diameter d favors the detection of low atomic concentrations. This is so

because the radiation damage is spread over a larger volume of material, permitting

a larger beam current or acquisition time. A thermionic emission source, capable of

providing a large beam current, is then preferable. On the other hand, the minimum

detectable number of atoms, MDN = (π/4)d

2

f

min

N

t

, is given by

MDN =

π

4

d

2

f

min

≈

2.7d

σ

k

(β, )

hN

t

σ

b

(β, )

(DQE)(D/e)

1/2

exp

t

2λ

e

(5.26)

For a given radiation dose D,asmall probe diameter d is required to detect the

minimum number of atoms, favoring the use of a field emission source.

As seen from Eqs. (5.25) and (5.26), MAF and MDM will be lowest for an ele-

ment with a high core-loss cross section σ

k

(β, ); in other words, a low-energy

342 5 TEM Applications of EELS

edge or an edge sharply peaked at the threshold. However, edges below 100-eV

loss present problems because σ

b

(β, ) is large (due to valence-electron excita-

tion) and the background is further increased by plural scattering. As discussed in

Section 4.4.3, SNR and therefore MDN and f

min

depend on the position and width

of the background fitting and integration windows.

Ignoring the exponential term and possible variation of DQE with E

0

,Eqs.(5.25)

and (5.26) predict that (MAF)

2

and (MDN)

2

are proportional to σ

b

σ

d

/σ

2

k

, where

σ

d

= e/D is a damage cross section. If ionization damage (due to inelastic scatter-

ing) prevails, these cross sections are all proportional to v

–2

(Section 5.7.5), so both

MAF and MDN should be independent of the incident electron energy. A computer

program is available for modeling energy-loss spectra, including instrumental and

shot noise, and is useful for predicting whether a particular ionization edge will be

visible for a given specimen composition and thickness and particular TEM operat-

ing conditions (Menon and Krivanek, 2002). Since electron dose to the specimen is

often the factor limiting resolution, dose-efficient recording is important; method-

ology and acquisition scripts have been developed to optimize the process (Sader

et al., 2010; Mitchell and Schaffer, 2005).

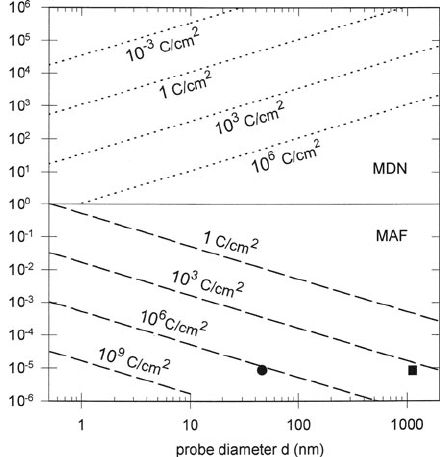

Figure 5.32 shows the detection limits for calcium (L-loss signal) within a

30-nm-thick carbon matrix, calculated for 100-keV incident electrons and parallel-

recording EELS. Single calcium atoms should be detectable with a sub-nanometer

probe, but would involve a high radiation dose; even in the absence of radiolytic

processes, D ≈ 10

6

C/cm

2

can remove six layers of carbon atoms by sputtering

(Leapman and Andrews, 1992). For larger probe sizes (or larger scanned areas in

STEM), the detection of Ca/C ratios down to a few parts per million is predicted, in

agreement with measured error limits of about 0.75 mm/kg or 9 ppm (Shuman and

Somlyo, 1987; Leapman et al., 1993b). Leapman and Rizzo (1999) have pointed out

that although electrons may destroy the structure of biological molecules, this does

not necessarily prevent an accurate measurement of elements such as Ca and Fe that

were originally present.

Although calcium represents a favorable case, the detection limits for phos-

phorus are comparable. From energy-selected CTEM images, Bazett-Jones and

Ottensmeyer (1981) reported a phosphorus signal/noise ratio of 29 from a nucle-

osome containing 140 base pairs of DNA (280 phosphorus atoms), equivalent to the

detection of 29 atoms at SNR = 3. Using a STEM and parallel recording spectrom-

eter, Krivanek et al. (1991a, b) measured the O

45

signal from clusters of thorium

atoms on a thin carbon film; quantification revealed that the signal originated from

just a few atoms.

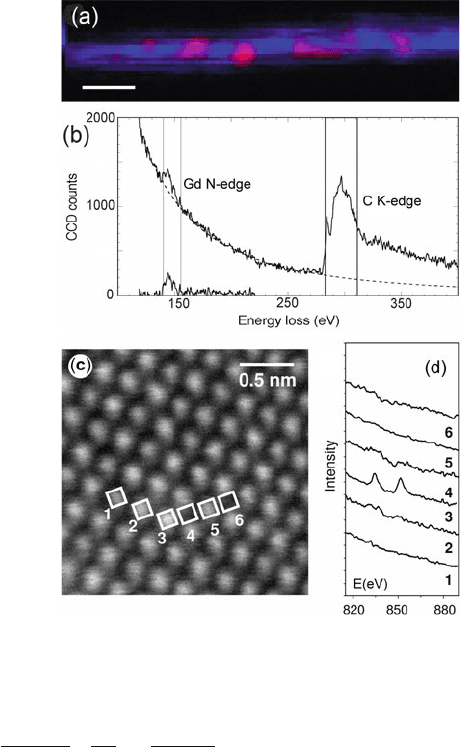

Suenaga et al. (2000) were the first to report images of single atoms whose

atomic number could be identified by EELS; see Fig. 5.33a. Gadolinium (Gd)

atoms were placed within C

82

fullerene molecules that were in turn encapsu-

lated within single-wall carbon nanotubes (forming so-called peapods). The 100-kV

STEM probe produced a radiation dose approaching 10

4

C/cm

2

but the atoms were

confined sterically and secondary electrons (which cause most of the damage in

fullerenes and organic compounds) would be free to escape. Even so, an assess-

ment of the number of atoms (from a background-subtracted Gd N-edge and using

5.5 Spatial Resolution and Detection Limits 343

Fig. 5.32 Minimum number of calcium atoms (dotted lines) and minimum atomic fraction of

calcium (dashed lines) detectable in a 30-nm carbon matrix (N

t

= 2.7 × 10

17

cm

−2

), calculated

from Eqs. (5.26)and(5.25) for different doses of 100-keV electrons. The calculations assume

DQE = 0.5, h = 9, λ

e

= 200 nm, β = 10 mrad, and = 50 eV and hydrogenic cross sections

σ

L

(β, ) = 9.9 × 10

−21

cm

−2

and σ

b

(β, ) = 1.9 × 10

−21

cm

−2

. The circular data point is from

Leapman et al. (1993b) and the square point from Shuman and Somlyo (1987), both experimental

data. For scanned probe analysis, the effective probe diameter is (4A/π)

1/2

, A being the scanned

area

a Hartree–Slater cross section of 8700 barn) yielded numbers between 0 and 4, sug-

gesting that some Gd atoms migrated along the nanotube and clustered together

under the intense irradiation. Subsequent measurements at 60 keV (Suenaga et al.,

2009)showedno observable movement of Er atoms, although Ca atom images

had 300 times less intensity than expected from the L-shell cross section (4700

barn, = 10 eV), suggesting movement out of the beam during the electron

exposure.

Using an aberration-corrected STEM, Varela et al. (2004) identified single La

atoms in crystalline CaTiO

3

; see Fig. 5.33c. The signal/noise ratio was said to be

sufficient to determine the electronic properties (e.g., valency) of a single atom. The

authors point out that because of channeling, the intensity of different elemental

signals varies differently with depth, which could allow the depth of an atom to be

determined by comparison with computer simulations of probe spreading.

Riegler and Kothleitner (2010) have given a revised version of Eq. (5.25)forthe

case where the atomic fraction is measured using multiple least-squares fitting to

spectral standards, rather than background extrapolation and integration:

344 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Fig. 5.33 (a) Single Gd

atoms (red)insidea

single-wall carbon nanotube

(blue), recorded with a

650-pA 0.5-nm STEM probe

and (b) energy-loss spectrum

acquired in 35 ms from the

central pixel of a Gd atom

(Suenaga et al., 2000). (c)

ADF dark-field STEM image

of calcium titanate containing

4% La and (d)core-loss

spectra recorded with the

electron probe stationary at

positions 1–6, showing that

the atomic column at position

3 contained La, believed to be

a single atom. From Varela

et al. (2004), copyright

American Physical Society.

http://link.aps.org/abstract/

PRL/v92/p095502

MAF =

3

σ

k

(β, )

1.1

d

2

u

k

(D/e)N

t

(DQE)

−1/2

(5.27)

For the case of Cr in Al

2

O

3

(ruby), they calculate a minimum atomic fraction of

0.04% for a thermionic source TEM (0.3 nA beam current and 40 s recording

time) and 0.12% for a Schottky source TEM with monochromator (0.1 nA and 60 s

recording time).

It should also be noted that multivariate statistical analysis (MSA) can isolate

and remove noise components from spectrum image data (Borglund et al., 2005)

after visual identification of an “elbow” on the scree plot; see Section 4.4.4.It

seems likely that noise arising from background and matrix (N

t

) components can

be eliminated, whereas that associated with characteristic signal cannot. If so, Eqs.

(5.25) and (5.26) will overestimate MDN and MAF when MSA is employed and the

analyzed element is present in small concentrations.

5.5 Spatial Resolution and Detection Limits 345

5.5.4.1 Comparison with EDX Spectroscopy

The characteristic x-ray signal (number of detected photons) recorded by an EDX

detector in response to a probe current I within acquisition time τ is

I

x

= N(I/e) τω

k

σ

k

(π, E

0

) η

x

(5.28)

where ω

k

is the fluorescence yield and σ

k

(π, E

0

)isthetotal ionization cross section

for shell k; η

x

is the collection efficiency of the x-ray detector, including photon

absorption in the front end, the detector window, and the specimen. Using Eqs.

(5.20) and (5.28), we can compare the EELS signal I

k

and the x-ray signal I

x

acquired under the same conditions:

I

k

I

x

=

σ

k

(β, )

η

x

ω

k

σ

k

(π, E

0

)

exp

−t

λ

e

(5.29)

The exponential term (typically 0.3) represents loss of EELS signal as a result of

elastic scattering outside a typical collection aperture. Core-loss intensity is also

reduced by the aperture and because only that fraction lying within an energy range

of the ionization threshold is utilized. As a result, the cross-sectional ratio in

Eq. (5.29) is appreciably less than unity; 0.1 might be a typical value. However,

the x-ray fluorescence yield, which is close to 1 for K-lines of heavy elements, is

below 0.05 for photon energies below 2000 eV (ω

k

≈0.002 for carbon-K x-rays). In

addition, η

k

is below 0.1 even for an x-ray detector with a high solid angle (≈1 sr)

and considerably less for low-energy photons because of absorption in the specimen

and at the detector front end. As a result, the EELS signal is typically less than the

EDX signal for heavy elements but larger by a factor of several hundred for a light

element such as carbon.

A major advantage of EDX spectroscopy is t hat the background to the char-

acteristic peaks is relatively low. Moreover, this background can be subtracted by

interpolation rather than extrapolation, equivalent to h = 2inEq. (4.61), so that the

signal/noise ratio is

(SNR)

x

= I

x

/(I

x

+2I

b

)

1/2

(5.30)

For low elemental concentrations, I

b

cannot be neglected relative to I

x

and a model

for the background intensity I

b

is required in order to calculate detection limits (Joy

and Maher, 1977). As an alternative, Leapman and Hunt (1991) obtained the SNR

and (SNR)

x

from χ

2

values produced by MLS fitting to energy-loss and x-ray spec-

tra recorded simultaneously from test specimens (10-nm carbon films containing

small concentrations of F, Na, P, Cl, Ca, and Fe). The SNR/(SNR)

x

ratio is plotted

in Fig. 5.34 and suggests that EELS offers higher sensitivity for low-Z elements and

medium-Z elements with L

23

edges in the 30–700 eV range. Watanabe et al. (2003)

point out that this comparison was performed using very thin specimens and that the

relative sensitivity of the two techniques depends very much on specimen thickness.

EELS may be more sensitive for thicknesses (typically 30–50 nm) that provide good

346 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Fig. 5.34 Elemental sensitivity of EELS relative to EDX spectroscopy, assuming a parallel-

recording electron spectrometer and an x-ray detector with solid angle 0.18 sr (left-hand axis)

or 0.9 sr (right-hand axis). Based on second-difference MLS processing of both spectra and sig-

nal/background ratios measured using 100-keV incident electrons (Leapman and Hunt, 1991). The

increase in sensitivity between Cl and Ca is due to the emergence of white-line peaks at the L

23

edge

signal/noise ratio at an ionization edge, whereas EDXS provides better sensitivity

(at least for Cu–Mn alloys) in thicker specimens.

As explained in Section 5.6.1, the x-ray signal from an ultrathin specimen may be

somewhat more localized than the EELS signal recorded close to the corresponding

ionization edge. But in a typical specimen, the spatial resolution of the x-ray signal

is degraded by beam spreading, whose effect in EELS can be controlled by using a

spectrometer entrance aperture; see Section 5.5.2.

5.6 Structural Information from EELS

As discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, inelastic scattering in a solid is sensitive to the

crystallographic and electronic s tructure of a specimen, as well as its elemental com-

position. As a result, structural information can be obtained from the dependence

of the inelastic intensity on specimen orientation, from the angular dependence of

scattering, or from fine structure present in the low-loss or core-loss regions of the

energy-loss spectrum.

5.6.1 Orientation Dependence of Ionization Edges

In a crystalline specimen, the transmitted electron wavefunction can be written as a

sum of Bloch waves, the probability of inner-shell excitation being proportional to

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 347

the square of the modulus of this sum (Cherns et al., 1973). The total intensity dis-

tribution has the periodicity of the lattice, with nodes and antinodes whose position

within each unit cell is a sensitive function of crystal orientation ( Section 3.1.4). At

high energy loss, where electron scattering from inner shells is localized near the

center of each atom (Section 5.5.3), the core-loss intensity will therefore change as

the specimen is tilted about an axis perpendicular to the incident beam. In x-ray

studies, this is known as the Borrmann effect. While it represents a source of error

in EELS elemental analysis of crystalline materials, it can be used constructively to

determine the crystallographic site of a particular element, selected by means of its

ionization energy.

The orientation of a specimen relative to the incident beam determines the chan-

neling condition, which affects the rate of inner-shell ionization and the rate of x-ray

production, as discussed in Section 3.1.4. The ALCHEMI method of atomic site

determination is based on planar channeling (Spence and Taftø, 1983); the orienta-

tion dependence of x-ray emission is measured for two elements that lie on alternate

planes containing the incident beam direction. The crystallographic site of a third

element is then determined by comparing its x-ray orientation dependence with that

of the other two. An alternative axial channeling method involves measuring charac-

teristic x-ray signals from a matrix element and an impurity (atomic site unknown)

with the incident beam traveling first along a low-index zone axis and then in a ran-

dom orientation; the ratio of the fractional changes in signal gives the fraction F

of impurity atoms that lie on particular atomic columns of the matrix (Pennycook,

1988). To reduce the influence of experimental errors, Rossouw et al. (1989) applied

multivariate statistical procedures to the analysis of spectra recorded under several

zone axis diffraction conditions.

In the EELS case, primary electrons that have caused inner-shell excitation may

travel further within the specimen before being detected. In doing so, they are

again subject to channeling, which affects their probability of escape in a particular

direction (an effect known as blocking). If this direction is defined by a collection

aperture centered about the incident beam direction, the blocking effect of the crys-

tal on the inelastically scattered electrons augments the channeling of the incident

beam (equivalent to double alignment in particle-channeling experiments), and the

orientation dependence observed by EELS can be larger than that seen in x-ray

emission spectroscopy. If R is the factor by which an elemental ratio (ratio of the

core-loss signals due to two different elements present at nonequivalent crystal-

lographic sites) changes with orientation, one might expect (Taftø and Krivanek,

1982a)

R

EELS

= (R

x

)

2

(5.31)

However, factors related to the localization of inelastic scattering reduce R

EELS

rel-

ative to (R

x

)

2

. Characteristic x-rays can be produced by any energy loss above the

ionization threshold E

k

and if the core-loss intensity is proportional to E

−s

, the mean

energy loss is