Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

358 5 TEM Applications of EELS

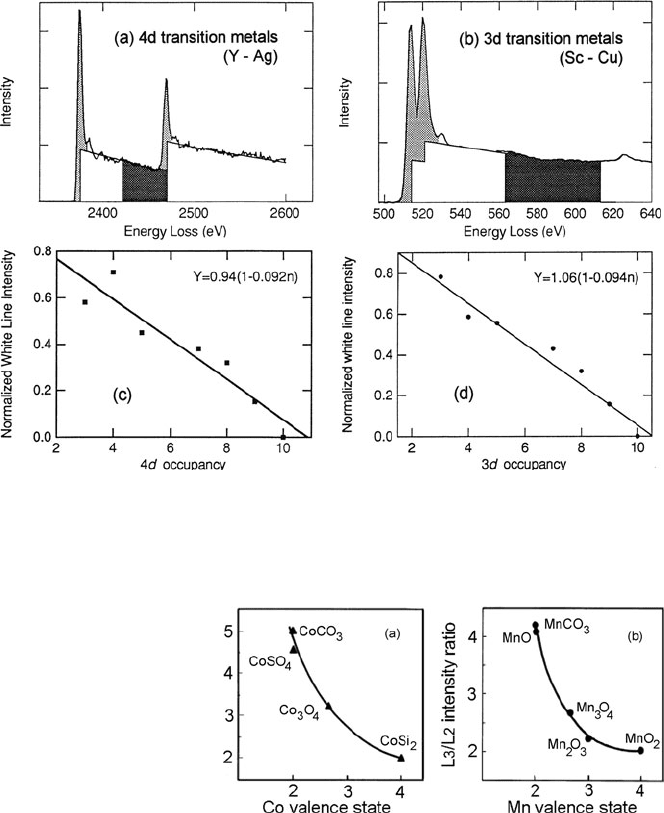

Fig. 5.41 Procedure used by Okamoto et al. (1992) to measure white-line/continuum ratio R

c

of

(a)4d transition metals and (b)3d transition metals. Graphs show the variation of R

c

with (c)4d

and (d)3d occupancy. Copyright, The Metals Society

Fig. 5.42 White-line

intensity ratio R

w

for (a)

cobalt and (b)manganese

compounds, as a function of

the cation valence. From

Wang et al. (2000), copyright

Elsevier

The white-line intensities I(L

2

) and I(L

3

) can be determined by curve fitting or by

a procedure similar to that of Fig. 5.41. The errors involved when different methods

are applied to manganese compounds are discussed by Riedl et al. (2006). Wong

(1994) has shown (for the case of nickel and its silicides) that variations in R

w

can

result from solid-state effects, besides variations in d-state occupancy.

A systematic study of a large number of chromium compounds, covering six

valences and two different spin states, was reported by Daulton and Little (2006).

Measurement of L

3

/L

2

ratio employed a method similar to Fig. 5.41, with the ratio

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 359

between the two continuum backgrounds initially set at 2 but then made equal to the

derived L

3

/L

2

ratio, this iteration being repeated 10 times. Continuum lines having

zero slope gave less scatter in the results and were consequently adopted. High-

spin Cr(II) compounds were easily distinguished by their high L

3

/L

2

ratio (1.9–2.4),

other groups being hard to distinguish on the basis of L

3

/L

2

ratio alone.

White-line ratios at the iron L

23

edge were used to study the conditions for ferro-

magnetism in amorphous alloys (Morrison et al., 1985). R

c

remains approximately

the same as germanium is added to iron, showing that the d band occupancy is unal-

tered and that the gradual loss of ferromagnetism cannot be explained in terms of

charge transfer in or out of the 3d band. However, R

w

does change, indicating redis-

tribution of electrons between the d

5/2

and d

3/2

sub-bands with a change in spin

pairing, which may account for the change in magnetic moment. Measurements on

a crystalline Cr

20

Au

80

alloy showed that the L

3

/L

2

white-line ratio increased by a

factor of 1.6 compared to pure chromium, indicating a substantial shift in spin den-

sity between j = 5/2 and j = 3/2 states, which may be the reason for a sevenfold

increase in the magnetic moment.

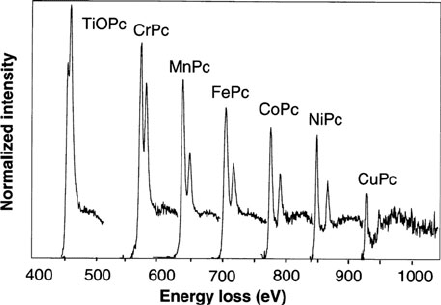

Koshino et al. (2000) recorded L

23

edges from vapor-deposited films of phthalo-

cyanine bonded to various transition metals. They found I

w

∝ 3d-state vacancy;

see Fig. 5.43. Comparison of their measured branching ratio I(L

3

)/[I(L

2

) + I(L

3

)]

with values calculated by Thole and van der Laan indicated a high spin state for the

compounds FePc, MnPc, and NiPc.

L

3

/L

2

ratio can be displayed as an intensity map. This was done using EFTEM

imaging by Wang et al. (1999) in order to display variations in the valence state of

Mn and Co in mixed-valence specimens.

5.6.4.1 Spin-State Measurements

Small changes (a few percent) in the L

3

/L

2

ratio of transition metals have been used

to determine electron spin state. For this purpose the L-edge has been measured

Fig. 5.43

Background-subtracted L

23

edges of metal

phthalocyanines. From

Koshino et al. (2000),

copyright Elsevier

360 5 TEM Applications of EELS

at selected points in the diffraction pattern, in a crystalline specimen of chosen

thickness. Differences occur because of interference between the inelastically

scattered waves and can be interpreted in terms of the mixed dynamic form fac-

tor (Schattschneider et al., 2000). Termed energy-loss magnetic chiral dichroism

(EMCD) by analogy with x-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD), TEM mea-

surements offer the promise of higher spatial resolution. Applied to biomineralized

magnetite crystals in magnetotactic bacteria, a spatial r esolution of 2 nm has been

demonstrated (Stöger-Pollach et al., 2011). Zhang et al. (2009) used EMCD to con-

firm the ferromagnetic nature of ZnO nanoparticles doped with transition metal

atoms. Future aims include the study of magnetic properties at interfaces, of vital

importance for spintronic and magnetic storage devices (Schattschneider, 2011).

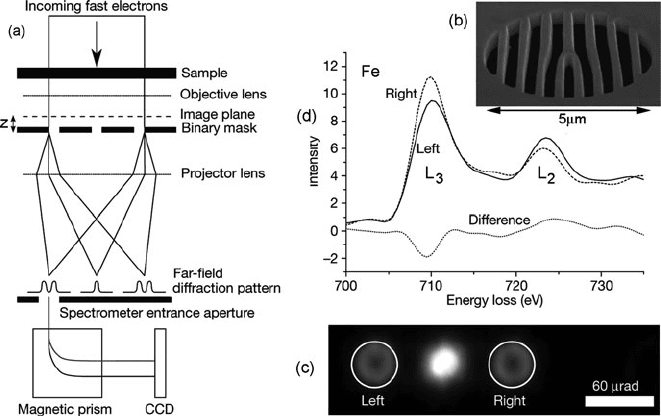

Verbeeck et al. (2010) have advocated the use of a holographic mask, taking the

form of computer-generated aperture (made by FIB milling of a Pt foil), to produce

a vortex beam in the TEM with a spiral wavefront and orbital angular momentum.

The idea was tested with a ferromagnetic iron sample; see Fig. 5.44. Compared to

the previous angle-resolved method of measuring chirality, this technique promises

improved signal/noise ratio and greater convenience, as the specimen thickness and

orientation do not need to be specially chosen.

Fig. 5.44 (a) Scheme for dichroic measurement using a computer-generated mask (b) placed a dis-

tance z beyond focus of a specimen image, together with a spectrometer entrance aperture located

(c) at the left or right sideband of the far-field diffraction pattern. ( d) L

3

and L

2

edges recorded

from a 50-nm-thick iron specimen for the two positions of the entrance aperture, together with

the difference signal that indicates asymmetry of the m =±1 dipole transitions (Verbeeck et al.,

2010). Copyright 2010, Nature Publishing Group. See also Schattschneider et al. (2008)

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 361

5.6.5 Use of Chemical Shifts

The threshold energy of an ionization edge, or changes in threshold between differ-

ent atomic environments (chemical shift), can provide information about the charge

state and atomic bonding in a solid. In the past, EELS chemical shift measure-

ments have been of limited accuracy compared to those carried out by photoelectron

spectroscopy, but the situation has improved with the development of highly sta-

ble high-voltage and spectrometer power supplies and dual-recording detectors

(Gubbens et al., 2010). As discussed in Chapter 3, the EELS chemical shift rep-

resents a net effect, involving both the initial and final states of a core–electron

transition. Coordination number also has an influence, accommodated in the concept

of coordination charge (Brydson et al., 1992b).

Muller (1999) has argued that for metals the core-loss shift arises mainly from

changes in valence band width arising from changes in atomic bonding, rather than

charge transfer. EELS could therefore provide information about the occupied states

in a metal. While the spatial difference method (Section 4.4.5) can detect core-level

shifts as small as 50 meV, these shifts could be misinterpreted as indicating a change

in the density of states at an interface (Muller, 1999).

A simple example of chemical shift is the change in energy of the π

∗

peak from

284 eV in graphite to 288 eV in calcite (Fig. 5.37) as a result of highly electroneg-

ative O atoms surrounding each C atom. Martin et al. (1989) found that the carbon

K-edge recorded from calcium alkylaryl sulfonate micelles, which contain a cal-

cium carbonate core surrounded by hydrocarbon molecules, can be represented as

a superposition of the K-edges of calcite and graphite. Peaks in the carbon K-edge

fine structure of nucleic acid bases were similarly interpreted by Isaacson (1972b)

and Johnson (1972) in terms of chemical shifts of the π

∗

peak, arising from the

different environments of carbon atoms within each molecule. They reported a peak

shift proportional to the effective charge at each site (Kunzl’s law).

For silicon alloys, Auchterlonie et al. (1989) showed that the energy of the first

peak at the Si L-edge was displaced by an amount proportional to the electronega-

tivity of the nearest-neighbor atoms (B, P, C, N, and O); see Fig. 5.45. On the basis

of this shift and the near-edge structure, their amorphous alloys could be uniquely

identified. Brydson et al. (1992a, b) explained the shape of the oxygen K-edges of

the minerals rhodizite, wollastonite, and titanite in terms of the potential at each of

the oxygen sites.

To simultaneously measure the spectra across gate-dielectric multilayers, Kimoto

et al. (1997, 1999) used spatially resolved EELS, with a slit placed in front of the

electron spectrometer. The SREELS technique ensures that high-voltage fluctua-

tions do not introduce systematic errors, as can happen when spatial resolution is

achieved by scanning a small probe.

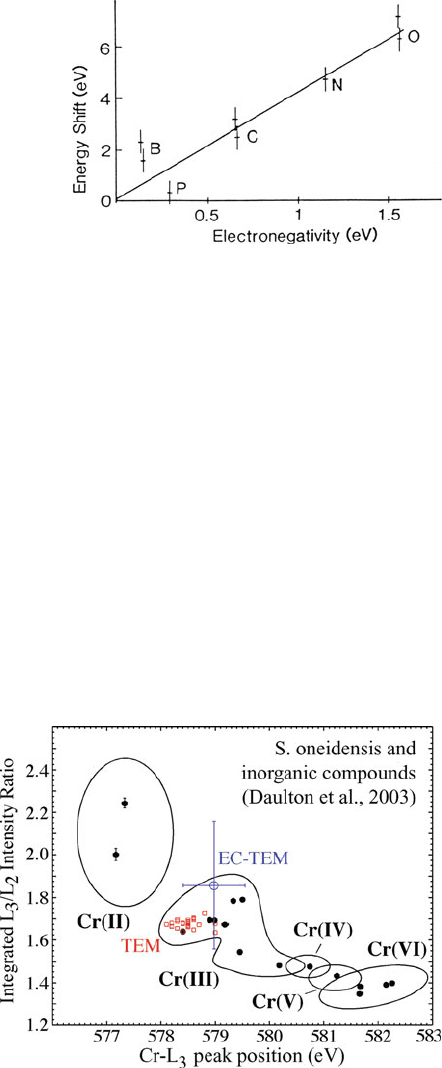

Daulton and Little (2006) measured the chromium L

3

threshold energy of many

Cr compounds, calibrating their energy-loss spectrometer to 855.0 eV for the Ni-L

3

edge of NiO. Their results were plotted against L

3

/L

2

ratio and showed a clear cor-

relation but considerable scatter, suggesting that other factors (coordination, low- or

362 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Fig. 5.45 Energy shift of the

first peak at the silicon L

23

edge, plotted against Pauling

electronegativity (relative to

Si) of ligand atoms. From

Auchterlonie et al. (1989),

copyright Elsevier

high-spin configuration, spin–orbit interactions, Coulomb repulsion, and exchange

effects) influence the L

23

edge structure. While it appeared easier to distinguish

between the common oxidation states, Cr(III) and Cr(VI), on the basis of chemical

shift rather than L

3

/L

2

ratio, the authors argue that both measurements are neces-

sary for the unambiguous determination of valency in transition metal compounds.

Daulton et al. (2003) made similar L

3

/L

2

and chemical shift measurements on anaer-

obic Shewanella oneidensis bacteria, using an environmental cell to keep specimens

hydrated in the TEM. The data fell within the Cr(III) region (see Fig. 5.46), con-

firming these bacteria as active sites for the reduction of toxic Cr(VI) species in

chromium-contaminated water.

5.6.6 Use of Extended Fine Structure

As discussed in Section 4.6, a radial distribution function (RDF) specifying inter-

atomic distances relative to a particular element can be derived by Fourier analysis

Fig. 5.46 Chromium L

3

/L

2

ratio plotted against L

3

threshold energy for

inorganic compounds,

together with data for S.

oneidensis measured in

vacuum (square data points)

and in an environmental cell

(central data point with large

error bars). Each circular data

point represents the mean and

standard deviation of

measurements on a particular

compound. Reproduced from

Daulton et al. (2003), with

permission from Cambridge

University Press

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 363

of the extended fine structure (EXELFS), starting about 50 eV beyond an ioniza-

tion edge threshold. This procedure has been tested on various model systems and,

after correction for phase shifts, has yielded first and second nearest-neighbor dis-

tances that agree with x-ray measurements to accuracies between 0.01 and 0.001 nm

(Johnson et al., 1981b; Kambe et al., 1981; Leapman et al., 1981; Stephens and

Brown, 1981; Qian et al., 1995).

Higher precision is possible when measuring changes in interatomic distance

in specimens of similar chemical composition. The RDF of sapphire (α-Al

2

O

3

)

and amorphous (anodized) alumina in Fig. 4.22 shows a change in Al–O dis-

tance of 0.003 nm. No measurable shift in the nearest-neighbor peak occurred after

crystallizing the amorphous layer in the electron beam, consistent with the crystal-

lized material being γ - rather than α-alumina (Bourdillon et al., 1984). Aluminum

K-edge EXELFS was used to investigate the structure of ion-implanted α-Al

2

O

3

using cross-sectional TEM specimens (Sklad et al., 1992). Implantation at −185

◦

C

with 160-keV Fe ions (4 × 10

16

cm

−2

) produced a 160-nm amorphous layer that

recrystallized epitaxially to α-Al

2

O

3

upon annealing in argon at 960

◦

C. Oxygen-

edge EXELFS required a restricted energy range because of the presence of an iron

L

23

edge at 708 eV. Implantation with a stoichiometric mixture of Al and O ions

produced an amorphous layer that recrystallized into a mixture of γ -Al

2

O

3

and

epitaxial α-Al

2

O

3

, as determined from Al K-edge EXELFS; see Fig. 5.47.

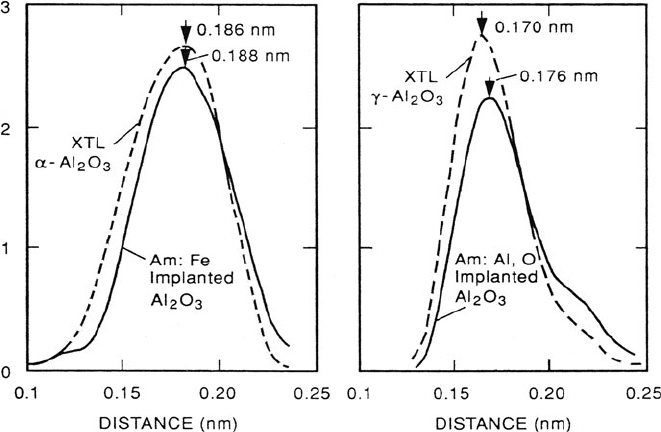

Fig. 5.47 Nearest-neighbor peak in the RDF obtained from Al K-edge EXELFS of (a) α-Al

2

O

3

implanted with 160-keV Fe ions (4 × 10

16

cm

–2

), compared with the crystalline substrate and (b)

a layer implanted with a stoichiometric mixture of Al and O ions, compared with γ-Al

2

O

3

made

by annealing for 1 h in argon. Data have been corrected for phase shifts using empirical correction

factors. From Sklad et al. (1992), copyright Taylor and Francis

364 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Batson and Craven (1979) used a field-emission STEM to record K-edge

EXELFS from amorphous carbon films, revealing differences in RDF depending

on whether the substrate was mica or KCl. These results demonstrate that, even

with serial recording, EXELFS was able to provide structural information from very

small areas, below 10 nm in diameter. As always, the fundamental limit to spatial

resolution is radiation damage, but the problem can be acute in EXELFS studies

because of the need to achieve excellent signal/noise ratio in the tail of an inner-shell

edge.

Noise statistics are improved in the case of lower energy edges; the Si L-edge

from SiC was found to be sensitive to the atomic environment up to the sixth

coordination shell (Martin and Mansot, 1991). However, low-energy EXELFS is

difficult to analyze quantitatively, partly because of the high pre-edge background

and restricted energy range imposed by other ionization edges. At the opposite

extreme, EXELFS of the titanium K-edge (4966 eV), measured using 400-keV elec-

trons and parallel recording (Blanche et al., 1993), yielded results comparable with

synchrotron radiation EXAFS. Kaloyeros et al. (1988) used boron edge EXELFS to

investigate the high-temperature stability of amorphous films of titanium diboride,

made by electron-beam evaporation onto liquid-nitrogen-cooled substrates.

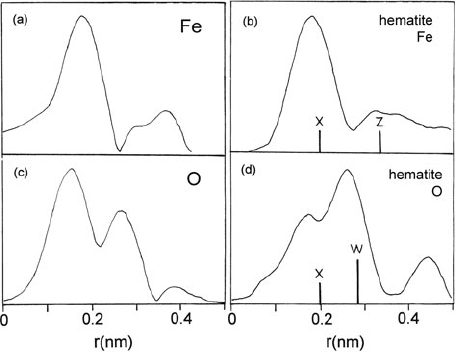

As an example of a biological application, Fig. 5.48 shows RDFs recorded from

iron-rich clusters (siderosomes) extracted from lung fluids of a patient suffering

from silicosis (Diociaiuti et al., 1995). The Fe-L

23

RDF is similar to that recorded

from a hematite standard but the RDF from the oxygen K-edge exhibits a displaced

Fig. 5.48 Radial distribution functions for (a)Featomsand(c) O atoms, obtained from EXELFS

of alveolar macrophages (siderosomes). The iron and oxygen RDF recorded from hematite are

givenin(b)and(d), where vertical bars marked X, Z, and W show the expected Fe–O, Fe–Fe, and

O–O interatomic distances. From Diociaiuti et al. (1995), copyright EDP Sciences (Les Éditions

de Physique)

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 365

nearest-neighbor peak and a second-nearest-neighbor (O–O) peak of reduced inten-

sity compared to hematite. These discrepancies were explained by assuming that

oxygen is also present in a protein coat surrounding the biomineral core, forming

short O=C bonds that shift the center of the first peak to lower radius. Diociaiuti

and colleagues (1991, 1992a, b) recorded EXELFS from chromium, copper, and

palladium clusters in order to quantify the increase in nearest-neighbor distance (up

to 5%) with decreasing particle size and the effect of oxidation.

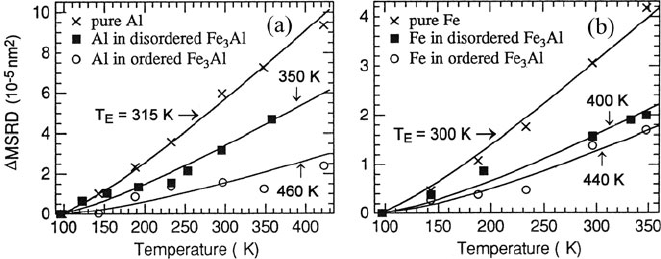

EXELFS measurements as a function of temperature enabled Okamoto et al.

(1992) to study ordering in undercooled alloys, particularly chemical short-range

order that is difficult to measure by techniques such as diffuse x-ray scattering. The

temperature dependence of the mean-square relative displacement (MSRD) was

used to deduce Einstein and Debye temperatures, good agreement being obtained

with force-constant theory and with previous experimental data. Differences in

Einstein temperature between ordered and disordered alloys, reflecting difference

in vibrational states, are illustrated in Fig. 5.49. Since the EXELFS data can in prin-

ciple be obtained from small specimen volumes, measurement of a local Debye

temperature might usefully characterize the defect density at interfaces or in small

precipitates (Disko et al., 1989).

To achieve the 0.1% statistical accuracy that is desirable for analyzing EXELFS

data, as many as 10

6

electrons need to be recorded within each resolution element

(typically 2 eV). Careful monitoring of relative peak heights within each readout

can alert the operator to damage and changes in specimen thickness within the beam

(Qian et al., 1995). High-voltage and spectrometer drift can be corrected by shifting

successive readouts back into register. It is important to carefully remove diode array

dark current and gain variations (Section 2.5.5).

Even with parallel recording, EXELFS analysis requires an incident electron

exposure of typically 10

−7

C. For a 1-μm-diameter incident beam, this is equivalent

Fig. 5.49 Temperature dependence of the nearest-neighbor mean-square relative displacement

(MSRD) measured for (a)Aland(b) Fe a toms in pure elements and in chemically disordered

and ordered Fe

3

Al. All values are relative to measurements made at 97 K; solid lines represent

the Einstein model, with an Einstein temperature T

E

as indicated. From Okamoto et al. (1992),

copyright TMS Publications

366 5 TEM Applications of EELS

to 1 C/cm

2

dose, enough to destroy the structure of most organic specimens and even

some inorganic ones (see Section 5.7.3). Because most damage-producing inelastic

collisions involve energy losses outside the EXELFS region, electrons may produce

more damage than the monochromatic x-rays used in EXAFS studies (Isaacson and

Utlaut, 1978; Hitchcock et al., 2008). If there exist materials in which structural

damage takes place only as a result of inner-shell scattering, this conclusion would

not apply (Stern, 1982). Provided radiation damage is not a problem, the TEM is

competitive with synchrotron sources in the sense that the EXELFS recording time

is typically less than that of EXAFS for ionization edges below 3 keV (Isaacson and

Utlaut, 1978;Stern,1982).

The core-loss intensity is improved by increasing the collection semi-angle β,

but at the expense of a higher pre-edge background (Section 3.5). If β is too large,

nondipole contributions complicate the EXELFS analysis, but such effects are usu-

ally assumed to be small (Leapman et al., 1981;Disko,1981); see Section 3.8.2.For

100-keV electrons, a semi-angle in the range 10–20 mrad should allow dipole theory

to be used, while transmitting typically half of the core-loss scattering. However, this

large angle will average out the directional dependence of EXELFS (Section 3.9),

so a much smaller value of β is necessary to study the directionality of bonding.

5.6.7 Electron–Compton (ECOSS) Measurements

Electron energy-loss spectra are most often recorded with a collection aperture cen-

tered on the optic axis, around the unscattered beam. If this aperture is displaced or

the incident beam tilted through a few degrees so that only large-angle scattering is

collected, a new spectral feature emerges at high energy loss in the form of a broad

peak; see Fig. 5.50. Known as an electron-Compton profile, this peak represents a

cross section (at constant scattering vector q) through the Bethe ridge; see Figs. 3.31

and 3.36. Its center corresponds to an energy loss E that satisfies Eq. (3.132),the

scattering angle θ

r

being determined by the collection aperture displacement or the

tilt of the incident beam. For sin θ

r

<< 1 and E << E

0

, Eq. (3.132) is equiv-

alent to the relation E = γ

2

Tθ

2

r

for Rutherford scattering from a free stationary

electron.

The fact that the atomic electrons are not free is indicated by the width of the

Compton profile, which is a measure of the electron binding energy. Therefore,

although the peak contains overlapping contributions from both outer- and inner-

shell electrons, the latter give a much broader energy distribution and contribute

mainly to the tails of the profile. Conversely, the central region represents mainly

scattering from bonding (valence) electrons.

The spread of the Compton peak can also be thought of as a Doppler broaden-

ing due to the “orbital” velocity or momentum distribution of the atomic electrons,

closely related to the electron wavefunctions. Quantitative interpretation (Williams

et al., 1981) is rather similar to the Fourier method of EXELFS analysis. After sub-

tracting t he background contribution from the tails of lower energy processes, the

5.6 Structural Information from EELS 367

Fig. 5.50 (a) Energy-loss spectrum of amorphous carbon, recorded using 120-keV electrons scat-

tered through an angle of 100 mrad. Zero-loss and plasmon peaks are visible (because of elastic

and multiple scattering), in addition to the carbon L-edge and Compton peak. The dashed curve

shows a computed free-atom Compton profile. (b) Reciprocal form factor derived for amorphous

carbon (solid line) and for two basal plane directions in graphite. From Williams and Bourdillon

(1982), copyright IOP Publishing

energy scale is converted to one of momentum (or wave number k) of the atomic

electron. The Fourier transform of the resulting profile (Fig. 5.50b) is known as a

reciprocal form factor B(r) and is the autocorrelation function of the ground-state

atomic wavefunction, in a direction specified by the scattering vector q (i.e., by

the azimuthal location of the detector aperture). If the specimen is an insulating or

a semiconducting crystal, zero crossings in B(r) are expected to coincide with the

lattice s pacings.

The optimum scattering angle for recording the electron-Compton profile from

a light element sample (such as graphite) appears to be about 100 mrad for

60–100 keV electrons, resulting in a profile whose center lies at about 1 keV loss.

An energy resolution of 10 eV is sufficient, but should be combined with an angu-

lar resolution of about 3 mrad (Williams et al., 1984). The signal/background ratio

at the Compton peak is maximized by making the sample as thin as possible,

indicating that the background arises from plural or multiple scattering, chiefly

large-angle elastic (or phonon) scattering accompanied by one or more small-

angle (low-loss) inelastic events. Because of the large width of the Compton peak,

accurate subtraction of the background is not easy. To obtain a tolerably low back-

ground, the specimen thickness should be less than about 30 nm in the case of

100 keV incident energy and a low-Z element such as carbon. Even thinner sam-

ples are appropriate for higher Z elements and would result in l onger recording

times.

Because of the need for both angular and energy discrimination, the collec-

tion efficiency of the Compton signal is of the order of 10

−6

, assuming parallel

recording. Adequate statistics within the Compton peak involve recording at least

10

6

electrons, requiring an incident exposure ≈3 × 10

−3

C, equivalent to a dose of