Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

388 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Spectrum imaging offers the possibility of extensive data manipulation after

spectrum acquisition. For example, it allows segmentation to be used for measuring

small concentrations of elements in particular organelles. Regions of similar com-

position can be recognized by examining the K-edges of major constituents (C, N,

O) and spectra from these regions can be summed to provide adequate statistics for

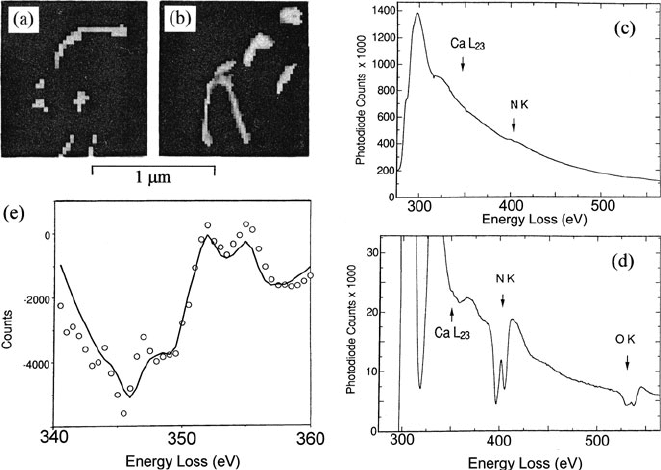

measuring average trace element concentrations. Leapman et al. (1993b)usedthis

technique to measure calcium concentrations (50–100 ppm) in mitochondria and

endoplasmic reticulum (see Fig. 5.67) with a precision of better than 20%. Further

discussion of the quantitative procedures involved is given in Aronova et al. (2009).

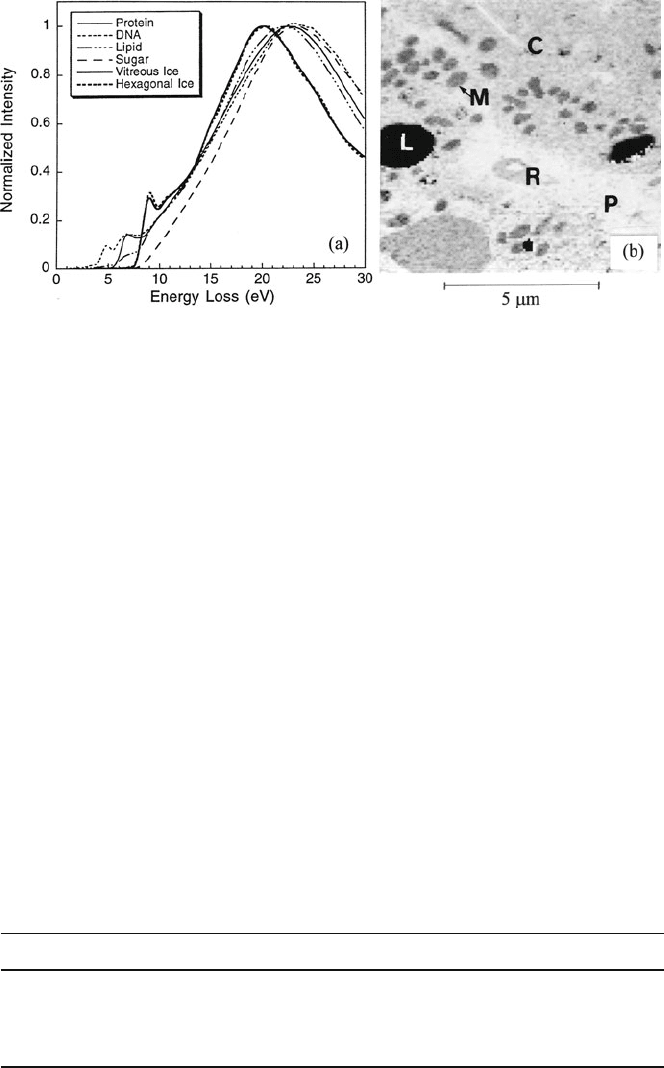

The low-loss spectra of biologically important substances exhibit a broad peak

around 23 eV, whereas ice shows a peak around 20 eV and a sharp rise around 9 eV,

probably due to excitation across the bandgap; see Fig. 5.68a. Sun et al. (1995)

exploited these differences in fine structure to measure the water content within

cells, with a precision of around 2% and a spatial resolution of 80 nm. Their pro-

cedure involved MLS fitting of spectrum image data (6–30 eV region) to standard

spectra from ice and protein. They also produced maps of water content, showing

pronounced differences between mitochondria, cytoplasm, red blood cells, plasma,

Fig. 5.67 (a, b) Regions of endoplasmic reticulum in mouse cerebellar cortex, segmented on

the basis of their nitrogen content. (c) Spectrum obtained by summing contributions from both

segmented regions. (d) First-difference spectrum, showing a weak Ca L-edge. (e)MLSfitofthe

Ca L-edge data points to a CaCl

2

reference spectrum. From Leapman et al. (1993b), copyright

Elsevier

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 389

Fig. 5.68 (a) Low-loss spectra of protein, DNA, lipid, sugar, and ice. (b) Water map of frozen

hydrated liver tissue: L = lipid droplets (zero water content), M = mitochondria (average content

57%), R = erythrocyte (65% water), P = plasma (91% water). From Sun et al. (1995), copyright

Wiley-Blackwell

and lipid components; see Fig. 5.68b. This same method has more recently been

applied to mapping the water distribution in skin tissue (Yakovlev et al., 2010).

5.7.5 Radiation Damage and Hole Drilling

As discussed in Section 5.5.4, radiation damage provides a basic physical limit to the

spatial resolution of electron-beam analysis, so there is considerable interest in min-

imizing this damage. The basic damage mechanisms are summarized in Table 5.3,

together with some ways of reducing their effect (Egerton et al., 2004).

As discussed in Chapter 3, electrons undergo both elastic and inelastic scattering

in a TEM specimen. Elastic scattering below 100 mrad, used to form diffraction

patterns and bright-field images, involves negligible energy transfer (<0.1 eV) and

no damage to the specimen. However, electrons scattered through larger angles

can transfer several electron volts of energy and cause displacement (or knock-on)

damage if the incident energy exceeds some threshold value, as discussed in

Table 5.3 Mechanisms of radiation damage

Mechanism Possible antidotes

Knock-on displacement Reduce E

0

below threshold, surface coating

Electron-beam heating Reduce beam current, cool the specimen

Charging (SE production) Reduce beam current (possible threshold)

Radiolysis (ionization damage) Cool the specimen, surface coating

390 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Section 3.1.6. High-angle scattering is a rare event, so knock-on damage is impor-

tant only at high electron doses (>1000 C/cm

2

typically) and is noticeable only

in conducting materials (particularly metals), where the high density of free elec-

trons prevents damage by radiolysis. The consequences are permanent displacement

of atoms within a crystal or at grain boundaries (Bouchet and Colliex, 2003) and

removal of atoms from the specimen surface (electron-induced sputtering). In the

latter case, a thin carbon surface coating has been shown to be effective in protecting

the specimen for a limited period (Muller and Silcox, 1995b).

Inelastic scattering involves significant energy transfer to the specimen, on the

average several tens of electron volts per scattering event. Most of this energy ends

up as thermal vibration (heat) but some goes into secondary electron (SE) produc-

tion, giving rise to electrostatic charging of insulating specimens. In addition, the

electron transitions involved in inelastic scattering can result in ionization damage

(radiolysis).

The average energy E deposited in a specimen, per incident electron, can be

evaluated from its energy-loss spectrum:

E=

EJ(E)dE

#

J(E)dE (5.36)

where the integration is over the entire spectrum including the zero-loss peak

(Egerton, 1982b). Because Eq. (5.36) includes plural scattering contributions to

J(E), E increases more than linearly with specimen thickness. Assuming that

only a small fraction of the energy transfer goes into SE production and radiolysis,

the temperature rise in the beam can be estimated by equating the rates of energy

deposition and heat loss, giving

IE(t/λ

i

) = 4πκt(T − T

0

)/[0.58 +2ln(2R

0

/d)] +(π/2)d

2

εσ(T

4

−T

4

0

) (5.37)

where I is the beam current (in A), E is in eV, and λ

i

is the total inelastic mean

free path. Radial heat conduction is assumed, κ being the thermal conductivity of

the specimen, R

0

the distance between the beam and a thermal sink (e.g., grid bars,

assumed to be at the ambient temperature T

0

); d is the electron beam diameter.

Heat loss by radiation from the upper and lower surfaces of the specimen is

represented by the last term in Eq. (5.37), ε being the emissivity of the specimen and

σ Stefan’s constant. However, in almost all cases this term is negligible compared to

the conduction term (Reimer and Kohl, 2008). The temperature rise T = T −T

0

is

then approximately independent of specimen thickness and depends mainly on the

beam current (not current density) and only logarithmically on the beam diameter:

for I = 5nA,T increases from 0.5

◦

to 1.5

◦

Casd decreases from 1 μmto0.5nm

(Egerton et al., 2004).

The temperature rise is usually negligible for small probes, whereas for beam cur-

rents of many nanoamperes, it can be tens or hundreds of degrees (Reimer and Kohl,

2008). In beam-sensitive specimens such as polymers, the result can be melting or

warping of the specimen, especially when accompanied by electrostatic charging.

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 391

Reducing the beam current is helpful, even if it results in a longer exposure time

to acquire the data. Because radiolysis occurs more rapidly at higher temperature,

beam heating may account for the higher radiation sensitivity of polymer films at

higher dose rate (current density) observed by Payne and Beamson (1993).

Radiolysis occurs because the electron excitation is not necessarily a reversible

process: when an atom or molecule returns to its ground state, the chemical bonds

with neighboring atoms may reconfigure, resulting in a permanent structural change.

In crystalline specimens, structural disorder is seen as a disappearance of lattice

fringes and a gradual fading of the spot diffraction pattern (Glaeser, 1975; Zeitler,

1982). The disruption of chemical bonding can be seen more directly as a disappear-

ance of the fine structure in an optical-absorption and energy-loss spectra (Reimer,

1975; Isaacson, 1977). Radiolysis may also result in the removal of atoms from the

irradiated area, known as mass loss. This process is of concern in elemental analysis

by EELS or EDX spectroscopy because some elements are removed more rapidly

than others, resulting in a change in chemical composition.

5.7.5.1 Damage Measurements on Organic Specimens

Although radiation damage is detrimental to electron-beam measurements, EELS

has proven useful for examining the sensitivities of different types of specimen, the

damage mechanisms involved, and ways of reducing the damage. Core-loss spec-

troscopy has been used to monitor the loss of particular elements from organic

specimens, while low-loss or core-loss fine structure has been used as a measure

of structural order.

The dose required for a single measurement is reduced if the spectrum is col-

lected from as large an area of specimen as possible. In TEM image mode, this

implies a low magnification and a large spectrometer entrance aperture. If a spec-

trum is recorded at a time t after the start of irradiation, the accumulated dose is

D = It/A, where I is the beam current and A the cross-sectional area of the beam

at the specimen. The remaining amount ( N atoms/area) of a particular element is

calculated from its ionization edge, making use of Eq. (4.65). If log(N) is then plot-

ted against D, the initial slope of the data gives the characteristic or critical dose

D

c

(the dose that would cause N to fall to 1/e of its initial value, if the kinetics

remained strictly exponential). The value of D

c

is an inverse measure of the radiation

sensitivity of the specimen.

Measurements on organic materials have shown that mass loss depends on the

accumulated dose and not on the dose rate (i.e., D

c

is independent of current den-

sity). Table 5.4 lists D

c

for selected organic compounds exposed to 100-keV incident

electrons. Values for other incident energies can be estimated by assuming D

c

to be

proportional to the effective incident energy: T = m

0

v

2

/2 (Isaacson, 1977). Not

surprisingly, D

c

is low for compounds containing unstable groups such as nitrates.

Aromatic compounds are generally more stable than aliphatic ones, and it has been

proposed that damage to aromatics requires K-shell ionization (Howie et al., 1985).

Replacement of hydrogen by halogen atoms (as in chlorinated phthalocyanine) fur-

ther reduces the radiation sensitivity, due to the increased steric hindrance (cage

392 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Table 5.4 Characteristic dose for removal of specified elements from organic compounds by 100-

keV electrons (Egerton, 1982b; Ciliax et al., 1993)

Material Element removed D

c

(C/cm

2

) 300 K D

c

(C/cm

2

) 100 K

Nitrocellulose (collodion) C

N

O

0.07

0.002

0.007

0.4

0.3

0.6

Poly(methyl methacrylate)

(PMMA)

C

O

0.6

0.07

1

0.6

Copper phthalocyanine N 0.8

Cl

15

Cu-phthalocyanine Cl 4 >10

Perfluorotetracosane F 0.2 0.2

Amidinotetrafluorostilbene F 0.8 >10

4

effect) from surrounding atoms. Fluorine attached directly to an aromatic ring can

be remarkably stable, especially at low temperatures (Ciliax et al., 1993).

As seen in Table 5.4, cooling an organic specimen to 100 K reduces the rate

of mass loss, sometimes by a large factor. Cryogenic operation may not change

the number of broken bonds but it prevents atoms from leaving the irradiated area

by reducing their diffusion rate. EELS measurements confirm that gaseous atoms

leave the irradiated area when the s pecimen returns to room temperature (Egerton,

1980c). Lamvik et al. (1989) found that mass loss in collodion is further reduced at

a temperature of 10 K.

An alternative way of reducing mass loss is to coat the specimen on both sides

withathin(≈10 nm) film of carbon or a metal. Perhaps because each surface film

acts as diffusion barrier, mass loss is reduced by a factor of typically 2–6 (Egerton

et al., 1987). Carbon contamination films produced in the electron beam are believed

to have a similar protective effect. According to Fryer and Holland (1984), encapsu-

lation also helps to preserve crystallinity, perhaps by aiding recombination processes

or acting as an electron source.

Radiation effects can also be monitored from the low-loss spectrum, with a

lower dose required for measurement. From the plasmon peak intensity, Egerton and

Rossouw (1976) measured the rate of hydrocarbon contamination as a function of

specimen temperature and found that it became negative (indicating etching by oxy-

gen or water vapor) below −50

◦

C. By measuring a shift in the main plasmon energy

toward that of amorphous carbon, Ditchfield et al. (1973) found that polyethylene

loses a significant fraction of its hydrogen at doses as low as 10

−3

C/cm

2

. In addi-

tion, they observed the creation of double bonds (indicating cross-linking) from

the appearance of a π-excitation peak around 6 eV; in the case of polystyrene, an

initially visible π peak decreased upon irradiation, showing that double bonds were

being broken. Fine structure below 10 eV in the spectrum of nucleic acid bases grad-

ually disappears during the irradiation (Isaacson, 1972a). Doses that cause these

bonding changes are usually intermediate between those needed that destroy the

diffraction pattern (of a crystalline specimen) and the larger values associated with

mass loss (Isaacson, 1977).

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 393

Core-loss fine structure provides another indication of bonding, with the advan-

tage that different ionization edges can be recorded to determine the atomic site

at which damage occurs. In the case of Ge-O-phthalocyanine, Kurata et al. (1992)

found a decrease in the π

∗

threshold peak to be more rapid at the nitrogen edge than

at the carbon edge, suggesting chemical reaction between N and adjacent H atoms

released during irradiation. Conversely, the emergence of a π

∗

peak at carbon and/or

nitrogen edges has been observed during electron irradiation of fluorinated com-

pounds, providing evidence for the formation of double bonds and aromatization of

ring structures (Ciliax et al., 1993).

5.7.5.2 Damage Measurements on Inorganic Materials

TEM-EELS has also been used to investigate electron-beam damage to inorganic

materials. Hydrides are among the most radiation sensitive: a dose of 0.1 C/cm

2

con-

verts NaH to metallic sodium inside the electron microscope (Herley et al., 1987), as

seen from the emergence of crystalline needles whose plasmon-loss spectrum con-

tains sharp peaks. Metal halides are also rather beam sensitive: an efficient excitonic

mechanism results in the creation of halogen vacancies (F-centers) and interstitials

(H-centers), which may diffuse to the surface, resulting in the ejection of halogen

atoms (Hobbs, 1984). Halogen loss apparently depends on the dose rate as well

as the accumulated dose (Egerton, 1980f). Other radiolytic processes in inorganic

materials include inner-shell ionization followed by an interatomic Auger decay

(Knotek, 1984).

Thomas (1982, 1984)usedK-shell spectroscopy to monitor the effect of a field-

emission STEM probe on compounds such as Cr

3

C

2

,TiC

0.94

,Cr

2

N, and Fe

2

O

3

.The

dose required for the removal of 50% of the nonmetallic element was in the range

10

5

–10

6

C/cm

2

and did not change when specimens were cooled to 143 K, sug-

gesting a knock-on or sputtering process as the damage mechanism. Hole drilling in

silicon nitride was judged to be due to sputtering because the process occurred only

above a threshold incident energy (120 keV) and because the specimen thickness

decreased linearly (rather than exponentially) with time (Howitt et al., 2008).

A sputtering rate can be estimated from the displacement cross section σ

d

of the appropriate element, calculated as a Rutherford or Mott cross section

(Section 3.1.6), but only if the surface-displacement energy E

d

is known (Oen,

1973; Bradley, 1988). The latter is usually taken as the sublimation energy E

s

,but

E

d

= (5/3)E

s

appears to give better agreement with experimental data for metals

(Egerton et al., 2010). The sputtering rate in monolayers per second is then (J/e)σ

d

where J is the incident electron current density (e.g., A/cm

2

) and e is the electron

charge.

Because sputtering and bulk displacement processes are absent below some

threshold incident energy, considerable interest has been devoted to designing TEM-

EELS systems that work at lower accelerating voltages, while still achieving good

spatial and energy resolution. For example, a TEM fitted with a delta-type aberra-

tion corrector has achieved atomic resolution and 0.3-eV energy resolution at 30 kV

(Sasaki et al., 2010).

394 5 TEM Applications of EELS

5.7.5.3 Electron-Beam Lithography and Hole Drilling

High-brightness electron sources and aberration-corrected lenses allow the pro-

duction of nanometer-scale electron probes with very high current densities (>10

6

A/cm

2

) that can be quickly damaging to a TEM specimen. The implications for

nanolithography have also been explored, with high-density information storage

as one of the stated applications, and EELS has played an important part in these

investigations.

Muray et al. (1985) used a 100-kV field-emission STEM (vacuum of 10

−9

torr

in the specimen chamber) with a s erial-recording spectrometer to investigate beam

damage in vacuum-evaporated films of metal halides. After a dose of 1 C/cm

2

,a

50-nm film of NaCl is largely converted to sodium, as shown by the appearance

of sharp surface (3.8 eV) and volume (5.7 eV) plasmon peaks. A dose of 100

C/cm

2

removes the sodium, creating a 2-nm-diameter hole. Similar behavior was

observed for LiF but hole formation required only 10

−2

C/cm

2

. In the case of MgF

2

,

magnesium was formed (bulk plasmon peak at 10.2 eV) for D ≈ 1C/cm

2

but not

removed by prolonged irradiation. In CaF

2

, bubbles of molecular fluorine have been

detected from the appearance of a sharp peak at 682 eV (K-edge threshold) but only

with fine-grained films evaporated onto a low-temperature substrate (Zanetti et al.,

1994).

A finely focused electron beam can also create nanometer-scale holes in metal-

lic oxides. Sometimes hole drilling is seen only above a threshold current density,

typically of the order of 1000 A/cm

2

(Salisbury et al., 1984). The existence of this

threshold may indicate that a radial electric field around the beam axis (positive

potential at the center because of the high secondary electron yield of insulators)

must be established, of sufficient strength to remove cations in a Coulomb-explosion

process (Humphreys et al., 1990; Cazaux, 1995). The fact that the current den-

sity threshold for alumina was reduced by cooling the sample of 85 K (enabling

hole drilling to be performed with a tungsten filament electron source) suggests

inward diffusion of metal, less effective at low temperatures (Devenish et al.,

1989).

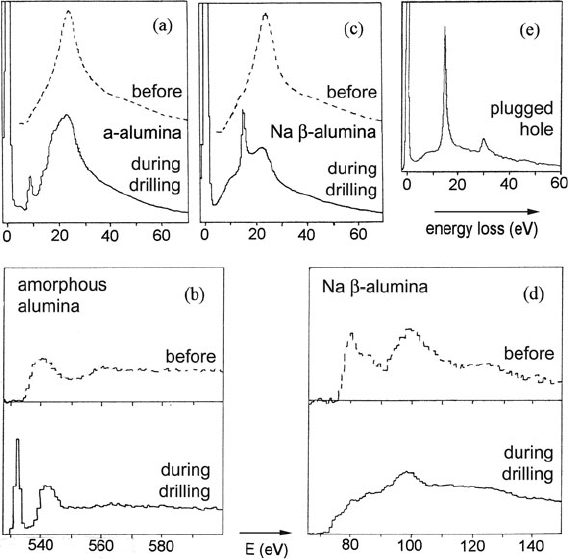

Berger et al. (1987) used their field-emission STEM to create holes in amor-

phous alumina. During drilling, the low-loss spectrum exhibited a peak at about

9 eV (Fig. 5.69a), the oxygen K-edge spectrum developed a sharp threshold reso-

nance (Fig. 5.69b), and the O/Al ratio, measured from areas under the O K- and Al

L-edges, increased from 1.5 to 7 or more, all consistent with the creation of a bubble

containing molecular oxygen. The bubble burst after an average time of 40 s, leav-

ing 5-nm-diameter hole. Hole drilling in sodium β-alumina proceeded somewhat

differently. A sharp peak appeared, with a shoulder at 9 eV and maximum at 15 eV

(Fig. 5.69c), suggesting surface and bulk modes in small Al spheres. At the same

time, the Al L-edge shifted 2 eV lower in energy and became more rounded in shape

(Fig. 5.69d), consistent with the formation of aluminum metal from an insulating

oxide. The oxygen K-edge gradually weakened, the O/Al ratio decreasing from 1.5

to 0.6 typically. Berger et al. (1987) suggested that oxygen is lost from both surfaces,

forming surface indentations that grow inward, leaving behind Al particles coating

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 395

Fig. 5.69 (a) Low-loss and (b) oxygen K-loss spectra of amorphous alumina, before and during

hole drilling. (c) Low-loss and (d)AlL-loss spectra of Na β-Al

2

O

3

before and during drilling.

(e) Low-loss spectrum of a hole plugged with aluminum. From Berger et al. (1987), copyright

Taylor and Francis Ltd

the inside walls. Although in most cases a hole is formed after 30 s, the zero-loss

intensity remained well below the incident beam current, indicating scattering from

Al within the incident beam. Occasionally, the hole became filled with a plug of

continuous aluminum, as evidenced by bulk plasmon peaks in the low-loss spec-

trum (Fig. 5.69e). This metallization is similar to the normal irradiation behavior of

halides such as MgF

2

.

Hole drilling has been demonstrated in many other oxides, with doses mainly in

the range 10

4

–10

6

C/cm

2

(Hollenbeck and Buchanan, 1990). In the case of crys-

talline MgO, square holes are formed from growth of an indentation on the electron

exit surface (Turner et al., 1990). Hole formation in metallic films such as aluminum

(Bullough, 1997) and metallic alloys (Muller and Silcox, 1995b) can be attributed

to electron-induced sputtering.

High-angle elastic scattering, which can lead to the displacement of atoms within

a crystal or sputtering from the surface of a specimen, is discussed in Section 3.1.6.

Displacement occurs only for an incident electron energy above threshold value,

396 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Table 5.5 Sublimation energy E

sub

and threshold energy E

0

th

for electron-induced sputtering of

elemental solids. The sublimation energy of carbon may be as low as 5 eV in an organic compound

or as high as 11 eV in diamond

Element symbol Atomic wt. AE

sub

(eV)

E

0

th

(KeV)

for E

d

= E

sub

E

0

th

(KeV)

for E

d

= (5/3) E

sub

Li 6.94 1.66 5.2 8.7

C 12.0 ≈8 ≈42 ≈68

Al 27.0 3.42 40 65

Si 28.1 4.63 56 91

Ti 47.9 4.86 97 154

V 50.9 5.31 111 175

Cr 52.0 4.10 89 142

Mn 53.9 2.93 68 109

Fe 55.9 4.29 100 158

Co 58.9 4.47 109 171

Ni 58.7 4.52 109 172

Cu 63.6 3.49 93 147

Zn 65.4 1.35 39 63

Ge 72.6 3.86 115 181

Sr 87.6 1.72 65 104

Zr 91.2 6.26 215 328

Nb 92.9 7.50 254 385

Mo 95.9 6.83 242 366

Ag 107.9 2.95 129 202

Ta 180.9 8.12 461 673

W 183.9 8.92 501 728

Pt 195.1 5.85 379 560

Au 197.0 3.80 270 407

From Egerton et al. (2010), copyright Elsevier

which in the case of electron-induced sputtering of elements can be calculated

from the sublimation energy E

sub

. As seen in Table 5.5, these threshold energies

are mostly below 200 keV, even if the surface-displacement energy E

d

is taken as

(5/3)E

sub

(Egerton et al., 2010).

The sputtering rate can be estimated as J

e

σ

d

/e monolayers/s, where J

e

is the

current density in A cm

–2

and σ

d

is a surface-displacement cross section in cm

2

.For

a field-emission source and aberration-corrected probe, J

e

can exceed 10

6

A/cm

2

,

giving sputtering rates of many nanometers per second. The predicted sputtering

rate is typically a few times lower if cross sections are based on a planar escape

potential (Section 3.1.6).

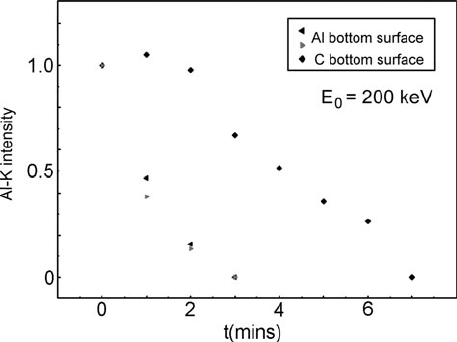

Alternatively, low-loss EELS can be used to measure the decrease in thickness

of a specimen with time, or core-loss measurements can reveal the loss of a specific

element. For example, Fig. 5.70 shows that aluminum is sputtered predominantly

from the bottom surface of a C/Al bilayer film; with carbon on the bottom surface,

loss of Al K-signal is delayed until the carbon is removed by sputtering. Because

sputtering is a slow process, a relatively high beam current is helpful for accurate

5.7 Application to Specific Materials 397

Fig. 5.70 Decrease in Al K-loss signal with irradiation time for a C/Al bilayer film, before and

after inversion in the TEM. Measurements were made in a TEM with a LaB

6

thermionic electron

source. Reproduced from (Egerton et al., 2006b), with permission from Cambridge University

Press

measurement of the sputtering rate, favoring the use of a thermionic (W-filament or

LaB

6

) electron source. A field-emission source can deliver a higher current density,

but with lower probe diameter and current. If the probe diameter is comparable to

or less than the depth of the crater formed by sputtering, some sputtered material is

re-deposited on the sides of the hole, reducing the measured thinning rate.